03 Feb The Battle of Manila: A Reflection and A Hope

By mark anthony cabigas, 3rd prize winner, battle of manila essay writing contest 2019.

The Battle of Manila of 1945 is one of the many bloody encounters between the American forces and the Japanese Army during the World War II in the Philippines. It lasted for 29 days and it devastated the City of Manila that cost 100,000 innocent lives and millions of pesos of invaluable heritage structures. Hence, it is considered to be the most brutal conflagration in the history of the Philippines. Nonetheless, despite the bad memories it left to millions of Filipinos, this battle is an important battle in Philippine History because this paved way to the attainment of actual independence. After the victory of the Americans in the Battle of Manila, the Commonwealth was eventually revived back in control of the Philippines. The revival of the Commonwealth was essential in the fulfillment of the transitory provisions of the Tydings-McDuffie Law – the concession law recognising Philippine Independence on 1946. Meaning to say, without the Battle of Manila, Philippines could have still been an exclave of the Japanese empire and Filipinos could have not able to establish their own de jure republic. Thus, the Battle of Manila was the key event that opened the opportunity for the Filipinos to finally actualize their dreams of independence and sovereignty from foreign control and even dependence.

However, despite its importance in our history, the Battle of Manila; the World War 2 and the rest of wars in Philippine history are taught in class apathetically — i.e., usually in knowing who were the leaders and whether who won and who lost in the battlefield. I claim because I experienced it myself. Textbook are even on that context. The leaders of war are the focus of the study but little empathy is given to every child’s broken future, to every woman who shattered their dignity, to every father who lost their moment to say even a farewell to their families. The people’s stories of pain, their stories of loss, their stories of eternal trauma are what more valuable than the leaders themselves, than the dates they fought, than the buildings they burnt. Indeed, I may know who Tomoyuki Yamashita, Sanji Iwabuchi and Douglas McArthur, but it is only today that I came to know the story of Julia Lopez who had her breasts sliced off and raped by the Japanese soldiers and had her hair set on fire; the story of the Manila Martyrs — Rev. Peter Fallon, Rev. John Heneghan, Rev. Patrick Kelly, and Rev. Joseph Monaghan, who were kidnapped and killed by the Japanese army; and of all the other terrible stories of loss and suffering during the infamous Manila Massacre and Rape.

Personally, it is important to me because this war is a reminder that I shall foster and cherish my freedom; protect the State’s security from invasion and from its downfall from corruption; and help in sustaining the Republic that our veterans of war have fought for before. Without the Battle of Manila and the eventual recapitulation of the city from the Japanese, I may be suffering the same way other Filipinos had experienced up until today. Moreover, as a future social science teacher, this battle is important to me because this urges me to teach and inspire my future students to love their country more than themselves, to protect and foster their independence and democracy but this time in a way that is diplomatic than through arms and ammunition. I also want to promote the ending of the culture of war and violence as an advocacy and rather promote diplomacy in any form of conflict. The Battle of Manila reminds us that in war, there is no winner, all become losers. And lastly I want to teach history to my future students with empathy and depth to the real victims of war. Today, we are commemorating this unpleasant history through monuments, shrines and markers. But memorares and markers of the Battle of Manila will remain concrete and steel markers and monuments respectively unless we are able to express our empathy and support to the victims and veterans of the war and to realize the fact that wars fruit no good to anyone.

No Comments

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

MilitaryHistoryNow.com

The Premier Online Military History Magazine

The Philippine Resistance – How WW2’s Forgotten Guerrilla Movement Helped Bring Down Japan

“ Guerrillas endured pervasive exhaustion, disease, and malnourishment. They engaged in irregular warfare, espionage, prison raids and sabotage.”

By James Kelly Morningstar

WHAT IF I told you that one of the most important campaigns of World War II – the Philippine Resistance — has been ignored?

Even the official U.S. Army history pronounced the “struggle for control” of the islands ended with the surrender of Corregidor in May 1942 and was not renewed until MacArthur returned in October 1944. [1]

Yet in that time Filipino guerrillas waged a war that denied Japan its strategic goals, altered U.S. grand strategy and helped transform America’s greatest military defeat into Japan’s greatest military disaster. Their fight also laid the foundation for a free and independent nation vital to the post-war order.

In my new book War and Resistance in the Philippines , 1942-1945 , I show how the interactions between the Japanese, Filipinos and Americans produced these historic outcomes.

Spurred by Germany’s success in Europe , the Japanese rushed their initial attack on the Philippines under the assumption that cooperation with native elites coupled with the military domination of the general population would pacify the country. [2] But as Tokyo’s planned 50-day campaign to subdue the islands turned into a 153-day slog, Japan’s troops encountered groups of determined guerrillas. Indeed, attempts to bully Filipinos by beatings, starvation and torture only motivated whole families to join the resistance. [3]

Japan’s efforts to have its army ‘live off the land’ and to expropriate Philippine resources further hurt the local economy and increased hardships. [4] The price of rice in Manila during the period rose two thousand percent. [5] Black markets thrived. People starved. Many women were forced into prostitution to support their families while many more were outright abducted by Japanese soldiers to serve as “ comfort women .” [6]

Not surprisingly, Japanese propaganda directed at Filipinos that emphasized Asian brotherhood failed to gain traction in population centers. Similarly, military action in remote areas failed to crush guerrillas. When Tokyo decided to make the Philippines the decisive battleground of the Pacific war in mid-1944, the guerrillas remained positioned to play a major role in that fight.

The war between Japan and the U.S. caught the Philippines in transition to national independence and riven by social and political divisions. Many Filipinos agreed to collaborate with the Japanese, often under instructions from the exiled government, in hopes of securing independence or protecting the people. Meanwhile, hundreds of others, like Wenceslao Q. Vinzons , Marcos V. “Marking” Augustin and Macario Peralta took up arms and organized resistance.

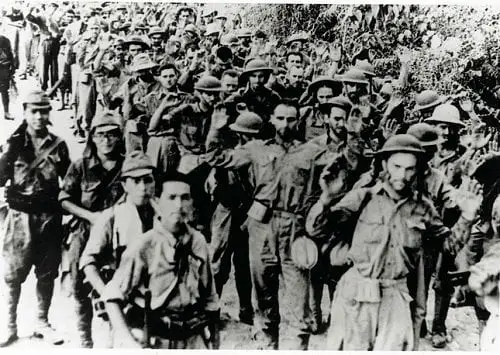

In time, up to 1.3 million Filipinos may have supported more than 1,000 guerrilla units. The U.S. Army would recognize 260,715 guerrilla in 277 units. [7] An estimated 33,000 guerrillas lost their lives. [8]

Guerrillas units independently chose whether or not to invite refugee U.S. soldiers into their movements. Many Filipinos, separated by pre-war rivalries, agreed to unite behind Americans who were likely to attract General Douglas MacArthur ’s support; others, like Peralta, chose to sideline Americans to safeguard their independence. [9]

Through clashes with rival factions, guerrilla leaders consolidated local power and created new basis for post-war government. Meanwhile, MacArthur’s promised return freed the guerrillas from having to defeat the Japanese occupation forces; they only had to prepare for the return of American conventional military forces.

MacArthur had taken tentative steps to organize guerrilla resistance by sending officers like Lieutenant Colonel John Horan to marshal insurgents on Luzon and ordering commanders on other islands to prepare their own irregular campaigns. His removal to Australia combined with Japanese threats against the 12,000 U.S. and 66,000 Filipino POWs undermined this effort.

Still Americans like Robert Lapham , Edwin Ramsey , Russell Volckmann and Wendell Fertig refused to surrender or escaped prison camps and became key guerrilla leaders in their own rights.

After sporadic radio traffic alerted MacArthur of the rise of Philippine guerrillas, he established the Allied Intelligence Bureau and the Philippines Regional Section to validate the resistance and develop it under his command.

In January 1943 the U.S. military inserted a team of Filipino soldiers under Major Jesus Villamor into Negros to coordinate the resistance. This was the first of 43 submarine missions that delivered supplies and agents over the next two years.

MacArthur tailored this support so as to develop reliable guerrilla groups and prevent any one leader from challenging his authority. He also isolated and checked groups deemed unreliable, like the “People’s Army to Fight the Japanese,” also known as the Hukbalaháp or Huks , which sought a Communist revolution in the Philippines and opposed the return of the exiled government. [10]

The Philippine resistance is a heroic tale of overcoming oppression and immense environmental challenges. Guerrillas endured pervasive exhaustion, disease, and malnourishment. They engaged in irregular warfare, espionage, prison raids and sabotage. They supported warfare on land, air, sea and undersea. Women played a large and dynamic role in the struggle, often as frontline fighters.

The scale of the resistance helped MacArthur convince President Roosevelt to approve his return to the Islands. [11]

Guerrillas would capture Japanese plans, conduct pre-invasion operations, guide invasion forces, and even serve as regular army combat units. With their support, MacArthur destroyed an army of 381,550 troops and nearly all of Japan’s remaining combat aircraft and naval vessels. [12] He also captured 115,755 Japanese prisoners – more than twice the number who surrendered on all other fronts during the entire war. [13]

Because of the guerrillas MacArthur got to return to the Philippines and Japan got the decisive battle it sought – just not with the outcome they desired.

[1] Louis Morton, The Fall of the Philippines, The War In the Pacific (United States Army in World War II) (Washington, D.C.: The U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1989), 582.

[2] Yuki Tanaka, Hidden Horrors: Japanese War Crimes in World War II (Boulder, Colorado: WestviewPress, 1996), 204.

[3] See Alfred McCoy’s study of Filipino kinship networks. Alfred W. McCoy, “‘An Anarchy of Families’: The Historiography of State and Family in the Philippines,” An Anarchy of Families: State and Family in the Philippines , ed. Alfred W. McCoy (Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Center for Southeast Asian Studies, 1993), 1, 10.

[4] Gene Z. Hanrahan, Japanese Operations Against Guerrilla Forces (Chevy Chase, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University, Operations Research Office, 1954), 5.

[5] Lizzie Collingham, The Taste of War: World War II and the Battle for Food. (New York: The Penguin Press, 2012), 243.

[6] Wallace Edwards, Comfort Women: A History of Japanese Forced Prostitution During the Second World War (North Charleston, South Carolina; Absolute Crime Books, 2013), 77-78.

[7] Larry S. Schmidt, American Involvement in the Filipino Resistance Movement on Mindanao During the Japanese Occupation , Master of Military Arts and Science Thesis, US Army Command and General Staff College, 5.

[8] This number comes from the Hunters’ guerrilla leader Colonel Eleuterio ‘Terry’ Adevoso who became head of the Philippine Veterans Legion after the war. A.V.H. Hartendorp, The Japanese Occupation of the Philippines, Vol. II. (Manila: Bookmark, 1967), 610.

[9] Russell W. Volckmann, We Remained: Three Years Behind the Enemy Lines in the Philippines (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, Inc., 1954), 5.

[10] Benedict J. Kerkvliet, The Huk Rebellion: A Study of Peasant Revolt in the Philippines (Berkeley: The University of California Press, 1977), 12.

[11] Most early American guerrilla leaders fell to disease and exhaustion and were replaced by a second wave of leaders who had spent the first year of the war sidelined by illness. Robert Lapham and Bernard Norling, Lapham’s Raiders: Guerrillas in the Philippines, 1942-1945. (Lexington, Kentucky: The University of Kentucky Press, 1996), 43.

[12] 255,795 of 381,550 were killed or died — nearly twenty percent of all Japanese soldiers who died during the war. Robert Ross Smith, Triumph in the Philippines (The United States Army in World War II: The War in the Pacific) (Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, 1933), 694,

[13] A total of 1,140,429 Japanese military personnel died in combat between 1937 and 1945; 485,000 against U.S. forces. John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War, (New York: Pantheon Books, 1986), 218.

Help spread the word. Share this article with your friends.

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

4 thoughts on “ The Philippine Resistance – How WW2’s Forgotten Guerrilla Movement Helped Bring Down Japan ”

- Pingback: Special Operations News Update - Monday, May 24, 2021 | SOF News

- Pingback: Not Your Grandfather’s Resistance: The Unavoidable Truths about Small States’ Best Defense Against Aggression – Modern War Institute | SWCS Soldier

My great uncle was shot down over the Philippines..twice. The second time he was unable to be rescued but instead fought with a resistance band until the return of US forces. He said they were the O Nine. Called that because they used 1909 Filipino pesos as their identification to each other. If detained the Japanese wouldn’t likely question why a Filipino had a coin in his pocket. I now have his coin.

My uncle, Lt. Zosimo Torrecampo of the Philippine Air Force and the rest of the airmen fled to Corregidor after their planes were razed to the ground by Japanese Zeros, but he joined the guerrillas. He survived the infamous Death March along with his cousin carlos Torrecampo of the Philippine Scouts

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

MHN’s FREE Newsletter

From the MHN Archives

Top Posts & Pages

© COPYRIGHT MilitaryHistoryNow.com

Skip to Main Content of WWII

July 4, 1946: the philippines gained independence from the united states.

In WWII’s aftermath, July 4 also became Independence Day for the Philippines in 1946.

Top Image: Commemorative stamps celebrating Independence Day from the collection of Dr. Ricardo T. Jose.

The 4th of July used to be considered an important national holiday in the Philippines. Not because it was the United States’ birthday, but because it was Philippine Independence Day in 1946. Seventy five years ago, the Philippines was recognized as an independent, sovereign country by the United States, which withdrew its authority over the archipelago as colonizer.

Pre-Independence History of the Philippines

The road to July 4, 1946 was long and tenuous. The Philippines had been a Spanish colony since 1565, and since that time numerous revolts broke out challenging Spanish rule. These revolts were disunited, however, until the nineteenth century when nationalism brought forth a more united anti-colonial movement. This culminated in a revolution that broke out in 1896. After much fighting, a stalemate ensued, leading to a ceasefire agreement between Filipino and Spanish leaders.

The outbreak of the Spanish-American War in 1898 brought Commodore George Dewey and the US Asiatic Squadron to Manila Bay, where they defeated the Spanish Asiatic fleet. The Philippine Revolution resumed in earnest, led by General Emilio Aguinaldo who established a revolutionary government. At the height of its military successes against Spain, the revolutionary government proclaimed independence on June 12, 1898. Aguinaldo became president and the Philippine Republic was formally inaugurated in Malolos, Bulacan, in January 1899.

The Spanish-American war was concluded by the Treaty of Paris which decreed that Spain would give up the Philippines, but in turn the archipelago would become a colony of the United States. Filipinos had not been consulted, and as a result the war for independence turned against the United States.

After over two years of fighting, Aguinaldo was captured and President Theodore Roosevelt declared the end of the Philippine-American War. The campaign for independence continued on the political front, even as sporadic violent resistance against American rule continued to break out.

In August 1916, the Jones Law, more formally known as the Philippine Autonomy Act of 1916, was passed, promising independence to the Philippines once Filipinos were able to prove that they could govern themselves. No timetable was set, but once the United States declared war on Germany in World War I, Philippine political leaders offered a division of Filipinos to fight on the side of the United States. Filipinos were given great leeway in running the government at that time, but once the Great War ended, the US government reexamined Philippine conditions and strengthened American control of the insular government. Filipinos sent regular independence missions to Washington to call for concrete steps towards independence, which were rebuffed by the prevailing Republican administrations.

The advent of the Great Depression made Congress rethink US-Philippine relations, and passed the Hare-Hawes-Cutting Act in 1933, over President Herbert Hoover’s veto. The Hare-Hawes-Cutting Act (HHC) envisaged a 10 year transitory period during which time the Philippines would establish a semi-autonomous government under an elected Filipino president. The act was rejected by the Philippine Legislature later that year, after much debate and political wrangling. Manuel L. Quezon, President of the Philippine Senate, proceeded to Washington immediately after to negotiate a more advantageous law, citing among others issues relating to the continuance of US bases in the Philippines after independence, the limits of authority of the Philippine president in the transitory government, and the abrupt end of Philippine preferential trade relations with the United States.

1934 Philippine Independence Act

Quezon, the dominant political leader in the Philippines at that time, believed he could influence the new American president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and the Democratic congress to rectify his main objections in a new Philippine independence bill. Roosevelt and the congress were busy with New Deal policies and were only willing to resuscitate the HHC with very minor changes. Quezon accepted these and returned to Manila. The ensuing act, the Tydings-McDuffie Law, was accepted by the Philippine legislature in May 1934, thus setting the stage for Philippine independence in 1946.

Under the Tydings-McDuffie Law, the Philippines would establish a government to be known as the Philippine Commonwealth, which would steer the Philippines through a 10-year transition period. After completing 10 years of nearly autonomous governance, the United States would withdraw its sovereignty over the islands on July 4 of the succeeding year, and would recognize the Philippines as an independent republic.

Prior to the establishment of the Philippine Commonwealth, a constitution had to be drafted. A constitutional convention was thus elected, and finished its draft in February 1935. Roosevelt approved this document, which was to become the legal framework not only of the Philippine Commonwealth, but also of the future Philippine Republic. It was approved in a nationwide plebiscite, and national elections for the new government were held in September 1935. The Philippine Commonwealth was formally inaugurated on November 15, 1935, an unprecedented world event in which the United States, a colonial power, was preparing to let go of its colony. The ramifications were keenly felt among other colonial governments and colonized people. Quezon was predictably elected as president.

The Philippine Commonwealth government had to resolve major problems during the 10-year transition period, among them national defense, social justice, economic development, national integration, and cultural identity. During the over three decades of American colonial rule, the Philippines had become dependent on the US economically, and had no armed forces of its own. These and major agrarian and labor problems had to be resolved. A Philippine Army was formed, and government enterprises in business were launched.

The Philippine Commonwealth was an untried experiment, and the Tydings-McDuffie Law appointed a representative of the US president in the form of a High Commissioner. Gone was the Governor General of earlier years. The High Commissioner would report on the progress of the Philippine experiment, and the US government had oversight functions over legislative, executive, and judicial actions of the Commonwealth. Furthermore, the US government held on to foreign affairs and currency matters. In case the experiment failed, the transition could be scrapped and it would be back to square one. Neither Quezon nor Roosevelt wanted this, so despite much power granted him, Quezon held back where he could.

World War II and the Filipino Guerrilla Movement

Halfway through the experiment, World War II broke out in Europe. Trade was disrupted, and the reality of war reaching the Philippines loomed. The gravity of some problems delayed enforcement of various plans, and some began to ask whether 10 years were enough. Quezon, however, attempted to advance independence at least privately, although this did not bear fruit.

The outbreak of war between Japan and China in 1937 also brought forth the specter of war, through refugees and news of defenseless cities being bombed. But it was the war in Europe that seemed closer: The European capitals were better known to most Filipinos, and the Blitzkrieg and the Battle of Britain became household words.

War did reach the Philippines in December 1941, although strenuous last-minute preparations were made. The US Army Forces in the Far East was created, placing under one command the US Army forces in the Philippines and the mobilized Philippine Army forces. Gen. Douglas MacArthur was placed in command, and modern aircraft and weapons were rushed to the Philippines. It was too late.

The Japanese struck before the defense preparations were completed, decimating the US air forces and naval facilities in the first days of the war. Beach defenses were unable to hold against the Japanese juggernaut, but a fighting withdrawal to Bataan and Corregidor was successful and held against all odds. Realizing the hopelessness of the situation, Roosevelt ordered MacArthur to Australia; the Philippine Commonwealth government, which had moved to Corregidor to save Manila from bombing, was itself also removed. Quezon would establish the Commonwealth government in exile in Washington as Bataan and Corregidor were forced to surrender. Roosevelt had, in the meantime, promised to redeem Philippine freedom and to pay for war damages,

For three years the Philippines was in the hands of the Japanese, who set up a military administration. Wanting to win Filipino loyalty, the Japanese declared the Philippines independent in 1943, ahead of the US promise. A government was set up, but most Filipinos saw through the Japanese aims and instead supported the guerrilla resistance movement. The guerrillas remained loyal to the Philippine Commonwealth and the United States, and were a major threat to the Japanese occupation forces.

Liberation of the Philippines from the Japanese

Gen. MacArthur, who had promised to return, landed in Leyte in October 1944, thus commencing the military campaign to liberate the Philippines from the Japanese. In the ensuing struggle, Manila and most of the major Philippine cities suffered grievous damage. MacArthur declared the military campaign on Luzon closed on July 4, 1945, but the bulk of the Japanese ground forces were still intact in the mountains. Fighting continued in Mindanao. And Japan had not yet surrendered.

The Philippine Commonwealth government returned with Gen. MacArthur. Quezon had died while in the United States, and Sergio Osmeña, the vice president, automatically took over. Osmeña landed with MacArthur on Leyte, and as the Battle of Manila neared its end, restored the government to Malacañang Palace in Manila. While in Washington, the Commonwealth government did all it could to hasten the return of American forces to the Philippines. It also sought to ensure that war damage would be rehabilitated by the US government. The Philippines actively participated in the early meetings that would result in the United Nations.

Upon his return to Manila, Osmeña pledged a Philippine Army division to participate in the assault landings on Japan. Guerrillas, now part of the army, trained accordingly. The atomic bombs negated the need for such action, and Japan accepted the Allied terms on August 15, 1945.

Post-war Rehabilitation

As the war ended, the Philippines counted the cost. Over a million Filipinos had died or were killed, out of a population of 18 million. Manila and most of the major cities were in ruins. Severe inflation had set in as a result of the Japanese occupation, and farms were fallow; farm animals too had died because of the war. Industries, transportation, and communication facilities were destroyed.

Should the original timetable for independence be kept? The tasks facing Osmeña and the Commonwealth government were daunting; none of this had been foreseen when the Tydings-McDuffie Act had become law.

Apart from the physical destruction and the loss of lives, the Philippines was divided: there had been those who had collaborated with the Japanese, while most had resisted either directly or indirectly. The country was split on whether the collaborators were to be dealt with harshly or not. Many key government officials from before the war had—willingly or not—served in the Japanese-controlled administration.

There was an immediate need for relief. People had to be fed, clothed, and given shelter. All the basic necessities were initially provided by the US Army—water, clothing, food, power, communications, and jobs. Other assistance came in from the United States and the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration as the piers were restored, and ships arrived.

Peace and order problems were serious—some stemming from the pre-war social and agrarian issues, others because of loose firearms. Guerrilla units were plenty, but not all were legitimate, and there was an upsurge of crimes. Morality was in tatters, as people had to survive in whatever ways they could. Inflation was rampant, even as the government strove to bring prices down with newly printed currency and price controls. Besides, after having been away for three years, it was a difficult task to win back the people’s confidence in the government.

The Philippine Congress was convened in June 1945—the first time it sat since the elections of November 1941. Some of its members had died during the war; others were tainted by charges of collaboration. It began its work of legislating, but was hampered by the unstable postwar conditions.

Osmeña travelled to the United States three times in 1945—a last meeting with FDR in April and two meetings with President Harry S. Truman, to negotiate aid and assistance for the Philippines—as well as assurances that independence would come as scheduled.

For a while an earlier independence date was broached, but this would have required legislation which was not a priority. There were mutterings that Philippine independence be delayed, owing to the unsettled conditions after the war, but this would mean political suicide to those seeking office. And so independence would take place as planned, on July 4, 1946.

The post-war Philippine Commonwealth faced severe problems not anticipated before the war. Land reform, reopening of schools, reconstruction, trials of suspected collaborators with the Japanese, recognizing and compensating veterans, restarting the economy, restoring trade, attracting investment—these and more had to be dealt with in the last months of the Philippine Commonwealth government.

The government was now more strongly reliant on the United States, more so than before the war. The Philippine Army was totally dependent on the US Army for equipment and weapons, and relief only coming from the United States. External defense would now be too costly for the cash-strapped government. Thus the presence of US bases could be seen as mutually beneficial.

The last American High Commissioner was Paul V. McNutt, who had served in that position in the late 1930s. He advised Osmeña on various matters. Secretary of State Harold Ickes insisted that the Philippines take a hard line on alleged collaborators—something that would be difficult to do due to the many issues involved. Ickes threatened to withhold assistance if the government did not punish those who had reneged on their oaths of loyalty to the United States.

Paul McNutt, High Commissioner to the Philippines, reads a proclamation at the ceremony. US Signal Corps photograph from the collection of Dr. Ricardo T. Jose.

An ally of the Philippines in Washington was Senator Millard Tydings, co-author of the pre-war Philippine Independence Act. He sponsored a bill granting what he felt were sufficient funds for rehabilitation. On a personal visit to the Philippines, however, he found out that earlier estimates had been underestimated, and that more funds were needed. His bill did allot a generous $620 million—later raised to $800 million—to the Philippines.

The Rehabilitation Bill was, however, tied to a trade bill, authored by Representative Jasper Bell. The Bell Trade bill sought to extend the free trade relations between the United States and the Philippines for another eight years, after which tariffs would be gradually imposed for 20 years. Bell insisted that to convince Americans to invest in the Philippines they had to be given the same rights as Filipinos. This necessitated amending the 1935 Philippine constitution, which limited land ownership, access to natural resources, among others, to Filipino citizens and majority Filipino-owned corporations. The parity amendment would thus become a requisite for receiving the bulk of the rehabilitation aid in the Tydings bill. The Bell Trade Bill also tied the Philippine peso to the US dollar and could not be independently revalued.

Other issues that emerged on the eve of independence. In February 1946, President Truman signed the Rescission Law, which denied most Filipino veterans of benefits due them, voiding their service in the US armed forces.

A strong US military presence remained in early 1946, with the 86th Infantry Division in full strength, prepared to protect American interests. With World War II over, many of its members felt their duty was done and rallied to be sent home. But there was discontent brewing in the provinces, with long agrarian issues remaining unsolved. Many military bases were still in US hands, and negotiations as to which would be kept after Philippine independence were begun. As set in the Tydings-McDuffie Act, the United States would maintain bases even after Philippine independence to protect American interests in the region.

Philippine Commonwealth Election of 1946

As the date of independence approached, a multitude of problems had to be solved. Amidst the disunity, tension, and uncertainty of the immediate post-war Philippines, there had to be a final election for the Commonwealth. Osmeña chose to run for reelection; Manuel Roxas, ambitious contender and also Quezon’s own choice as successor, ran against him. While Roxas had participated in the defense of the Philippines, he had also served in the Japanese-sponsored government under Jose P. Laurel. To some he was tainted with collaboration and might bring other collaborators back to power. Osmeña was the guerrillas’ choice, and also the peasants; Osmeña leaned left of center. But Roxas was backed by McNutt and General MacArthur.

Roxas won the election of April 1946, but by only a slim margin, garnering some 54 percent of the votes cast. He took his oath of office on May 28, 1946, in a temporary stage built in front of the ruins of the Legislative Building, as the third and last president of the Philippine Commonwealth.

Prior to his assumption of office, Roxas went to the United States via Tokyo, where he paid a visit to MacArthur. Roxas’ Washington visit was a frenzied week-long one, meeting with President Truman and ranking American officials to discuss Philippine affairs and concretize plans for US assistance to the Philippines.

As Roxas took office, conservative congressmen ousted more liberal legislators on unfounded charges. It marked a split between peasant leaders who were open to pursuing change in the government and conservatives who felt threatened by them. On the eve of Philippine independence, left-leaning peasant and labor groups threatened to secede and launch a rebellion, reacting to the blatant politicization of the congress.

Philippine Independence Day 1946

This was a big international event, but the Philippines did not yet have a Department of Foreign Affairs. It had to rely on the US government for much of the preparations.

May 1946 saw the start of a flurry of events to plan out the final days of the Commonwealth and prepare for Independence Day. A joint Filipino-American committee was formed to iron out details. The Manila Hotel, which had been gutted during the Battle of Manila, was cleaned up and prepared for gala events. Invitations were issued to distinguished guests from the United States and various countries. President Truman was invited, but he declined, owing to pressure of work. Independence related contests were launched—for an appropriate poster, essay, poem, and hymn. A US flag was to be hand-sewn by past and present Philippine first ladies, to be presented to President Truman. Commemorative postage stamps, medals, and other souvenirs were issued.

The venue for the independence rites was chosen and a stage shaped in the form of a ship’s prow (symbolizing the ship of state) was built with towering pillars behind it. The stage and grandstand were built in front of the iconic memorial of the Philippine national hero, Jose Rizal, in Luneta Park. A large arch was erected near it, in front of the Manila Hotel, to welcome visitors.

As the month of July 1946 began, so did the numerous events and preparations to climax in Philippine Independence on July 4. Private homes and government buildings were decorated. Bands paraded and gave concerts. The University of the Philippines’ Conservatory of Music held a gala concert at the Rizal Coliseum, where numerous international sports matches were held. Distinguished visitors from the US and other countries arrived. The US Navy’s Task Force 77 anchored in Manila Bay to salute the birth of the republic. It consisted of the flagship USS Bremerton , two aircraft carriers, two cruisers, and seven destroyers.

Among the Very-Important-Persons who arrived in the first days of July was General MacArthur, who flew from Tokyo. Representing the US government was High Commissioner McNutt, now destined to be the first US Ambassador to the Republic of the Philippines. From the United States were Senator Tydings, Representative Bell, US Postmaster General Robert E. Hannegan, former Governor General Francis B. Harrison, and others. Representatives from 27 nations arrived, among them the French WWI hero Lt. Gen. Zinovi Peckoff (at that time serving with the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers in Tokyo) and Lt. Gen. Sook Chatinakrob, Thailand’s Chief of Staff. In Manila Bay were Australian, Portuguese and Thai warships.

All these activities were taking place as the Cold War began: the United States tested an atomic bomb in Bikini Atoll on July 1. Communist-linked movements were beginning to threaten the post-war order.

On July 3, the Philippine Congress accepted the Bell Trade Act and authorized President Roxas to sign an executive agreement with the US laying the groundwork for formal negotiations and mutual recognition. That same day, Roxas and McNutt visited the commander of Task Force 77 on his flagship; later they recorded messages to be broadcast nationwide and to the United States. McNutt hosted a reception at his official residence and capped the day with a formal dinner in honor of Roxas at the Manila Hotel.

Thursday, July 4 1946, was a cloudy, sunless day. It was the rainy season in the Philippines, but this did not dampen the excitement building up towards the Philippine independence ceremony. Religious services were held in the various churches of Manila and provincial capitals, cities, and towns. Guests began arriving at the venue shortly before 7:00 in the morning. Dignitaries arrived from 7:20; the crowd craned their necks to get a glimpse of Gen. MacArthur. A bugle sounded, and the audience rose to welcome President Roxas and his wife at 7:55. He was followed by Vice President Elpidio Quirino and finally High Commissioner McNutt, accompanied by their respective wives.

With McNutt serving as emcee, the program began at precisely 8:00 am. The Rt. Rev. Robert F. Wilmer, ranking Protestant in the Philippines, gave the invocation. McNutt then introduced the speakers; there were wild cheers for Senator Tydings and Gen. MacArthur. Tydings reviewed the events which led to this day, and then wished the new republic “Godspeed.” MacArthur reviewed the “special relationship” between the Philippines and the United States.

The highlight of the program was McNutt’s reading of President Truman’s Proclamation of Independence. As he began speaking, a heavy downpour drenched the audience, but they braved the rain. The downpour lifted in time for McNutt to read the proclamation, which first laid out the legal basis for the United States’ acquisition of the Philippines, the United States’ desire to grant the Philippines independence, and the provisions of the Tydings McDuffie Act. Truman, as president of the United States, then withdrew all “rights of possession, supervision, jurisdiction, control or sovereignty” exercised by the United States over the territory and people of the Philippines, and recognized the independence of the Philippines.

McNutt ended with his own words:

“A new nation is born. Long live the Republic of the Philippines. May God bless and prosper the Philippine People, keep them safe and free.”

Paul V. McNutt

At 9:15 am, the US Army band played the US National Anthem as McNutt began lowering the American flag. President Roxas, pulling on the same cord, began raising the Philippine flag, to the accompaniment of the Philippine National Anthem, played by the Philippine Army Band.

As the United States and Philippine flags passed each other, they touched—“as if in a last caress, a last kiss,” wrote one witness. As the Philippine flag fluttered from the top of the flagpole, United States, Australian, Portuguese, and Thai warships in the bay fired a 21-gun salute. Church bells throughout the Philippines rang and a whistle announced that the Philippines was now independent.

Vice President Quirino then took his oath, followed by President Roxas. These were administered by Chief Justice Manuel V. Moran of the Philippine Supreme Court. Roxas proceeded with his inaugural address: “As we are masters of our own destiny, so too must we bear all the consequences of our actions,” he announced. The Philippines was no longer protected by the mantle of American sovereignty and thus “we must find our own way… [but in the atomic age] we cannot retreat within ourselves… On all fronts the doctrine of absolute sovereignty is yielding ground… But we have yet a greater bulwark today… the friendship and devotion of America… Our safest course is in the glistening wake of America whose sure advance with mighty prow breaks for smaller craft the waves of fear.”

The future direction of the Philippines under President Roxas was thus charted, and to highlight this orientation he and McNutt signed an agreement for the establishment of diplomatic relations and an interim trade agreement. Roxas now signed as president of the Republic of the Philippines, and McNutt as first US ambassador.

A chorus of one thousand voices—college students all—then sang the Philippine Independence Hymn. This had been the winner of the independence hymn contest composed by acclaimed composer Restie Umali. The official program ended with a closing Invocation by Most Reverend Gabriel Reyes, Filipino archbishop of Cebu.

As the program ended, a bugle call sounded at 11:00 am to signal the start of the civic-military parade. Units from the Philippine and US armed forces marched in splendor, followed by Filipino veterans of the 1890s revolution and WWII guerrilla members. As the aged revolutionary war veterans marched past the grandstand, US bombers and fighters flew overhead, spelling first a V for Victory, and then the letters P and R, representing the Philippine Republic.

The military contingents were followed by several floats from different government offices and schools. Of note was that of the General Auditing Office, represented by a bulldog watching over a safe. The last float contained figures of Filipinas (representing the Philippines) and Miss Columbia, representing liberty.

By noon the ceremony was over, and the dignitaries and audience retired. The day was not yet over, however. At 4:30 pm a tree symbolizing Philippine independence was planted in front of the Manila City Hall. At 7:00 pm President Roxas hosted a formal dinner, reception, and ball at the presidential palace. The historic day was capped by a grand fireworks display at the Sunken Gardens just outside the old Walled City of Intramuros, as US Navy ships put up a searchlight display and pyrotechnics show in Manila Bay.

Celebrations continued for two more days: in the afternoon of July 5, a Philippine sports exhibition was held at the University of Santo Tomas Gymnasium. That evening, a Gala Symphony Concert by the Manila Symphony Orchestra, was held at the Rizal Coliseum. The final celebration of the momentous week was a Barrio Fiesta—a dinner feast—in the evening of July 6 at the Manila Hotel.

1946 to Present Day

It was a time of great rejoicing. But as the new era dawned, there were numerous sticking points—the US bases, the Bell Trade Act, Philippine war damage claims, and discriminatory treatment of Filipino WWII veterans. The Military Bases Agreement was to last for 99 years, during which period there was no clear cut guarantee that these bases would protect the Philippines. The bases agreement was shortened in 1966, and finally lapsed in 1991. The Bell Trade Act extended free trade and required the granting of parity rights to American nationals, which in turn required amending the 1935 Constitution, which had reserved numerous rights to only Filipino citizens. Free trade, with quota limitations, would continue on until 1954, after which gradual tariffs would be applied for a period of 20 years, ending in 1974. Parity rights were granted American citizens after stormy debates which almost cost President Roxas his life. The Bell Trade Act also tied the peso to the US dollar until 1955.

July 4, 1946 thus saw the birth of the Philippine Republic, but with lots of unfinished business. And this amidst the backdrop of the developing Cold War, a civil war, and deep rooted problems.

The independence that was gained (restored, according to some pundits, referring to the 1898 declaration) was questioned—was it a real, total independence? In addition, Philippine Independence Day celebrations coincided with US Independence Day, resulting in some confusion in the Philippines and abroad. In 1962, President Diosdado Macapagal moved Philippine Independence Day to June 12, commemorating the 1898 Filipino proclamation. Aguinaldo was then still alive and was happy to see the change. July 4 had been an afterthought, opined some, with June 12 the real Filipino act.

July 4 became Republic Day, still a national holiday, in 1964. During the period of Martial Law under President Ferdinand Marcos, July 4 was changed to Philippine-American Friendship Day, and relegated to a working holiday. President Corazon Aquino did away with Philippine-American Friendship Day altogether, but President Fidel V. Ramos restored it on the occasion of the 50th anniversary.

The event 75 years ago was much welcomed at the time and did see the end of formal aspects of colonial rule. There was no longer direct US oversight, no more American High Commissioner, the Philippine flag flew alone (except in the US bases) and the Philippine National Anthem was played alone. But critics argued that it ushered in a neo-colonial relationship. Some trumpeted the Philippine-American relationship as a “special relationship,” but it did not seem so to others.

July 4, 1946 was overshadowed by the events of World War II. Commemorations of the 75th anniversary of key WWII events were many and well publicized, but were suddenly stymied by the Covid-19 pandemic. The 1946 independence ceremonies have also been overtaken by rites commemorating the 500th anniversary of Magellan’s arrival—and the bringing in of Christianity to the Philippines, which was given full support by the Philippine Government and the Spanish government. Given the importance of July 4, 1946, however, it is sad to see the day not recognized for what it was.

Meet the Author

Ricardo Trota Jose is professor of history at the University of the Philippines, Diliman. He obtained his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in history at U.P., and his PhD from the Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. He specializes in military and diplomatic history, with focus on the Japanese occupation of the Philippines. Jose has published widely in various journals and books. Among his major publications are The Philippine Army, 1935-1942 (Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1992) and Volume 7 (on the Japanese occupation of the Philippines) of the multi-volume Kasaysayan set (Reader’s Digest, 1998). He was awarded the Metrobank Foundation Outstanding Filipino in teaching in 2019.

This article is part of a series commemorating the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II made possible by the Department of Defense.

Explore Further

A Contested Legacy: The Men of Montford Point and the Good War

Despite their commendable service during World War II, the Marines of Montford Point would regularly contend with societal forces that vehemently resisted all measures taken toward racial integration.

Unaccounted For No More: Sgt. Harold Hammett

WWII US Marine Corps Sergeant Harold Hammett, fallen on Tarawa in 1943, is finally laid to rest in the family plot after 80 years.

The Fallen Crew of the USS Arizona and Operation 85

The Operation 85 project aims to identify unknown servicemen who perished aboard the USS Arizona during the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The Cairo and Tehran Conferences

In a series of high-stakes strategic conferences in late 1943, the Allies made several key decisions that shaped wartime strategy, while reflecting the changing balance of power between the Allied nations and foreshadowing the postwar emergence of the bipolar world.

'Cuidado!' The 158th Infantry 'Bushmasters' in the Pacific

“No greater fighting combat team has ever deployed for battle,” General Douglas McArthur noted after the war of the 158th Infantry Regiment “Bushmasters,” which was made up predominantly of Mexican Americans and members of the Pima and Navajo tribes from Arizona.

Delivering the Atomic Bombs: The Silverplate B-29

Most people are aware that Boeing's B-29 Superfortress was the plane that made the first atomic attacks. However, the B-29s delivering America’s first atomic weapons were far from ordinary.

General William H. Simpson and the Endgame in China

Operation Rashness, a major fall offensive intended to seize a port on China’s southeast coast, would open sea lines of communication into China for the first time in several years while providing a base of operations for the invasion of southern Japan.

Joseph Stalin and the Dissolution of the Comintern

On May 22, 1943, Moscow announced the dissolution of the Communist International.

10 Biggest Misconceptions About World War II In The Philippines

World War II was one of the largest and deadliest conflicts in human history, claiming the lives of millions and wreaking havoc on countries’ economies throughout the world.

Truly a “world war” in scope, virtually every country participated directly or indirectly in the war. For the Philippines, its own involvement came in the form of being occupied by the Japanese for three years.

Eager to grab the country’s natural resources, the Japanese drove out the Americans and became the new masters of the archipelago. Their reign—marked by numerous accounts of atrocities—alienated majority of the Filipinos who kept on fighting for their homeland right until the Americans came back to liberate the country.

Also Read: The WWII Japanese Soldier Who Hid in Philippine Jungle For 29 Years

According to the famous quote, the first victim of war is usually the truth, and with World War II here in our country, it’s no different. Over the years, many misconceptions have been made about certain facts, and thus it is only right to rectify them in order to set the record straight.

Note: This article in no way seeks to justify the unprovoked Japanese aggression and occupation of the Philippines but only seeks to give a clearer picture of what really happened during those dark and deplorable days.

1. Every Japanese treated our countrymen harshly.

Probably the biggest reason why some Filipinos—especially those belonging to the older generation—still harbor feelings of hatred for the Japanese is because of the brutality they suffered under their rule. We don’t blame them; after all, it is well-documented that life was generally a living hell for those who lived under the Japanese.

READ: The WWII Japanese Officer Who Became An Unlikely Philippine Hero

Contrary to popular belief, however, not all the Japanese acted like savage barbarians. In fact, there were some who actually displayed kindness towards the people. Chief Justice Abad Santos had fond memories of a Christian Japanese Captain named Watanabe who not only treated him and his son kindly but even delivered his letter to his wife.

Also See: General Masaharu Homma was sentenced to death [VIDEO]

Japanese officers, especially those who knew how to speak English, and their men were quite well-behaved and would even try to befriend the local Filipino community. While it won’t erase the stigma of their compatriots’ brutality, it’s also equally wrong to classify every single Japanese as a mindless murderer.

2. They controlled the entire Philippines.

While the Japanese did wrest the country from the Americans, a highly effective guerrilla force prevented them from ever taking full control of the country.

In fact, the Japanese controlled as much as only 40 percent; all the rest belonged to different guerrilla groups. While the Japanese did control the major urban centers, they were in fact confined mostly to Luzon and Visayas, surrounded by the guerrillas who operated in the countryside and in the mountains.

Related Article: 11 Reasons Why President Jose P. Laurel Was A Total Badass

One guerrilla movement in Mindanao—the island farthest from the Japanese—even installed its own government which operated out in the open. These groups’ non-stop destabilization and surveillance campaign against the Japanese proved to be hugely successful and were invaluable to the eventual return of the Americans.

3. The guerrillas were a united front.

In a way, the different guerrilla groups were united primarily that they had to fight a common enemy. However, the cause for unity ends there as these groups hated each other almost as much as they hated the Japanese. In fact, they often fought each other either for territory and influence.

Also Read: The Filipina Leper Who Became A WWII Spy

The Huks, for instance, despised American-led guerrilla groups and would often engage them in battle. The Moros also clashed with Filipino and USAFFE guerrillas on a regular basis. So in actuality, the conflict in the Philippines looked less like a clear-cut duel between two people and more like a barroom brawl among drunken customers.

4. The guerrillas were composed of Filipinos and Americans only.

While we may think that only Filipinos and Americans fought as guerrillas against the Japanese, there was actually another nationality that fought them here too: the Chinese.

That’s right, the Chinese—being also on the receiving end of Japanese aggression during the war—formed their own guerrilla group against the invaders. Composed mainly of assimilated Chinese, the Philippine Chinese Anti-Japanese Guerrilla Force or “Wah Chi” operated in Central Luzon and often conducted lightning raids and liquidations against the Japanese and their collaborators.

Also Read: Claire Phillips – “Manila’s Mata Hari”

They also fought together with the Huk. In fact, Luis Taruc was said to have remarked that among the guerrilla groups, the Wah Chi “were among the most courageous and ferocious.” Speaking of ferocity…

5. The guerrillas fought a good, clean fight.

To think that only the Japanese were brutal is misleading since various accounts have shown how creatively cruel our guerrilla forefathers could be as well. That Filipinos are an innately gentle and hospitable people just goes to show how far the Japanese actually forced them into becoming cruel sadists as well.

Fulfilling the proverb of “violence begets violence” and driven by revenge, the Filipino guerrillas struck fear into the hearts of the invaders, mutilating and decapitating captured Japanese soldiers whenever they could. One Japanese officer in Mindanao related how they would go back to sleep on their ships at night for fear of being ambushed by Moro juramentados . When the Americans finally returned, their cigarettes were often bartered with by the guerrillas using the severed heads of Japanese soldiers.

Trivia: A statue of a Japanese kamikaze pilot was built in Pampanga

The guerrillas also often ignored American orders to treat captured enemy soldiers well, killing and decapitating them the moment they could lay their hands on them. Even the Americans themselves were frightened at the behavior and appearance of the guerrillas, some of whom vowed not to shave or cut their hair until they’ve wiped out the enemy.

Again, only by the sheer cruelty of the Japanese were the Filipinos forced to become cruel themselves.

6. The American liberation campaign was unstoppable.

Believe it or not, General Douglas MacArthur almost didn’t get to keep his promise of returning to the Philippines in 1944, and it’s all thanks to some very critical mistakes the Americans made during the decisive Battle of Leyte Gulf. Luckily for them though, the Japanese made far more mistakes.

At this point, the Japanese were getting desperate and banking on a last-ditch gambit to delay or even possibly defeat the overwhelming American forces poised to land on Leyte. To do this, they consolidated what was left of their once-mighty Navy and devised a plan wherein a sacrificial decoy force would lure away the American’s most powerful ships which were guarding the invasion force.

With those out of the way, the Japanese would then swoop in with their own ships and destroy the unguarded forces.

Heartbreaking Photo: Homeless Filipino children amid WWII wreckage (1945)

The plan, if it succeeded, would have slaughtered a countless number of American soldiers as well as set the liberation campaign schedule back by years. And it nearly worked too.

Taking the bait, the powerful main fleet led by Admiral William Halsey pursued the decoys and allowed the Japanese Navy led by Vice-Admiral Takeo Kurita to sail unopposed through the San Bernardino Strait right into the unguarded American forces off the coast of Samar.

Up against this overwhelming force of battleships which included the Yamato (the largest of its kind in the world) and heavy cruisers was a motley collection of American support ships which consisted of slow-moving escort carriers, transports, and small destroyer ships.

However, the Americans displayed ferocious fighting skills in their engagement, their outgunned ships going toe-to-toe with the powerful Japanese battleships. In fact, Kurita lost his nerve and sounded the retreat because he thought he had been fighting the main American fleet.

7. MacArthur made his “I Shall Return” speech here.

With all the legends surrounding MacArthur, it’s probably no wonder if many Filipinos still think he announced his famous promise here on the Philippine soil.

In reality, however, MacArthur uttered that line only after he had arrived in Terowie, South Australia with the rest of the evacuees from Corregidor. He also kept repeating that line in his subsequent speeches.

Trivia: General Douglas MacArthur served as Manila Hotel’s “General Manager”

Incidentally, his colleagues and officials at Washington thought MacArthur’s line was too personal and asked him to change it to “We shall return”, a request he ignored. Besides, his supporters countered, MacArthur took the war personally since he thought he had let the Filipino people down and wanted to make amends.

8. The Japanese completely surprised our forces when the war began.

After the infamous attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, we were taught that the Japanese quickly launched “surprise” air raids on several bases across the Philippines.

One raid at Clark Airfield—which would be known as our own version of Pearl Harbor—resulted in the destruction of virtually the entire arsenal of USAFFE airplanes. As a consequence, the Japanese achieved air superiority at the onset of their invasion of the country.

It was a complete tactical surprise, right? Not really.

Since the attack on Pearl Harbor, USAFFE forces in the country had already been put on the alert for the impending Japanese onslaught. In fact, General Lewis Brereton, commander of the Far East Air Force even proposed sending bomber planes to destroy Japanese air bases in Formosa (Taiwan) to pre-empt their raids when he heard the news about Pearl Harbor. He also recommended that the planes be kept off the ground in order to prevent their destruction by the Japanese.

Related Trivia: The first American hero of World War II was killed in combat in the Philippines

However, bureaucratic squabbling between him and MacArthur’s Chief-of-Staff General Sutherland prevented the planes from launching the operation in time, an incident which has come to be known as the “Far East Air Force Controversy.” One Japanese airman who took part in the first air raids even expressed his surprise when he saw the American planes “like sitting ducks” on the ground.

Without the much-needed planes, the Filipinos and Americans found themselves at a huge disadvantage against the Japanese.

9. The Death March was Japanese brutality at its worst.

There is no question that the infamous Bataan Death March was one of Japan’s worst atrocities committed against the Filipinos and Americans. The 60-mile trek from Mariveles, Bataan in the south to Camp O’ Donnell in the north resulted in the deaths of tens of thousands of captured prisoners, many of whom succumbed to the grueling conditions of the march.

Curiously enough, many misconceptions have been attributed to such a well-documented event. For one, some prisoners described the long walk as relatively easy. According to them, their constant rest stops was the reason why the march lasted for at least three weeks.

And aside from the numerous accounts of Japanese cruelty, there were also stories of kind Japanese soldiers who helped out the prisoners, giving them water and allowing them ample time to rest. A few even allowed the weak ones to ride with them on their jeepneys or trucks. Unfortunately, acts of kindness like the aforementioned were the exceptions rather than the norm.

Also Read: Battle of Bataan (January 7 – April 9, 1942)

Another misconception is the view that surrendered personnel from Corregidor were transferred and forced to join the Death March. On the contrary, at the time of their surrender (May 6, 1942) the last of the Death March participants had already reached Camp O’ Donnell in Tarlac, their exodus having begun after the fall of Bataan on April 9. Instead, they were shipped to Manila and paraded on the streets as the Japanese wanted to show off their victory.

The Corregidor prisoners were also in far better shape (they enjoyed better rations) than their comrades who joined the Death March at the time of their surrender.

10. Every effect of Japanese Occupation was negative.

Was there ever a positive effect of Japanese rule of the Philippines?

While a decimated population, a destroyed economy, and a wrecked infrastructure would seem to negate that notion, there were indeed a few silver linings to be had during their occupation of the country. For one, Tagalog and not English became the national language. As a result, our culture experienced a sort of renaissance during those years especially when artists and writers re-discovered the beauty of indigenous arts and literature.

Related Article: Beautiful Old Manila Buildings Completely Destroyed By War

As we’ve mentioned before, the presence of a foreign invader also strengthened our national identity. Even if the guerrilla groups squabbled among themselves, they at least had the propensity to recognize the Japanese as a common enemy.

Lastly, the occupation showcased the positive qualities of Filipinos who not only had to be resilient but also be extremely creative to stay alive. Conclusively, the hardships of the war definitely strengthened the Filipinos’ indomitable will to survive

Cultural Bridge Productions, (n.d.). Amerikanitos, life during the japanese occupation of the philippines . [online] Available at: http://goo.gl/TJFzLX [Accessed 28 Oct. 2014].

Flores, W. (2012). Let us not forget Filipinos & Chinese fought together for freedom . [online] philSTAR.com. Available at: http://goo.gl/xXPNds [Accessed 28 Oct. 2014].

Gordon, R. (n.d.). Bataan, Corregidor, and the Death March: In Retrospect . [online] Battling Bastards of Bataan. Available at: http://goo.gl/Dxr2UK [Accessed 28 Oct. 2014].

Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines, (n.d.). The execution of Jose Abad Santos . [online] Available at: http://goo.gl/yFYmYE [Accessed 28 Oct. 2014].

Additional Sources:

Inside the Bataan Death March: Defeat, Travail and Memory By Kevin C. Murphy

Senso: The Japanese Remember The Pacific War: Letters To The Editor of Asahi Shimbun Edited By Frank Gibney And Translated By Beth Cary

In Our Image: America’s Empire in the Philippines By Stanley Karnow

The Edge Of Terror: The Heroic Story Of American Families Trapped In Japanese-Occupied Philippine By Scott Walker

Lapham’s Raiders: Guerrillas In The Philippines, 1942-1945 By Robert Lapham, Bernard Norling

The Young Draftee By Monte Howell

Combat Infantry: A Soldier’s Story By Donald E. Anderson

Battles That Changed History: An Encyclopedia of World Conflict By Spencer Tucker

Pain and Purpose In The Pacific By Richard Carl Bright

Treaty Cruisers: The World’s First International Warship Building Competition By Leo Marriott

The Soldiers’ Wall: A Glimpse Into Their World By Lyris Mitchell

The Most Dangerous Man In America By Mark Perry

The Filipino Moving Onward By Rosario Sagmit, Ma. Lourdes Sagmit- Mendoza, Ampara Sunga

US Commanders Of World War II (1): Army And USAAF By James Arnold, Robert Hargis

1942: The Year That Tried Men’s Souls By Winston Groom

Written by FilipiKnow

in Facts & Figures , History & Culture

Last Updated January 21, 2022 01:39 PM

FilipiKnow strives to ensure each article published on this website is as accurate and reliable as possible. We invite you, our reader, to take part in our mission to provide free, high-quality information for every Juan. If you think this article needs improvement, or if you have suggestions on how we can better achieve our goals, let us know by sending a message to admin at filipiknow dot net

Browse all articles written by FilipiKnow

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net

- Southeast Asia

- Philippines - Marcos, Aquino and History After World War II

INDEPENDENCE FOR THE PHILIPPINES AFTER WORLD WAR II

The Philippines was the first Southeast Asia country to gain independence after World War II On July, 4, 1946, the U.S. granted the Philippines formal independence. Manual Roxas became president. The independence movement had been going on for some time. See Early Filipino Independence Movement, Jose Rizal, the Philippine-American War, Movement Towards Independence

Roxas was installed as president of the Republic of the Philippines under the auspices of the United States and undertook the immense task of rebuilding a war-torn nation that had many severe problems even before the war began. After World War II the Philippines endured crippling high-interest loans ubder the guise U.S. 'aid', and its society and infrastructure— including more than three-quarters of its schools and universities—lay in ruins.

In the early years after World War II Philippines was viewed as the major intermediary between the West and Asia as it was located in Asia but a large portion of its population spoke English and practiced Catholicism. To help get war-devastated nation back on track and serve its own self-interest the United States gave the Philippines economic aid in return for 99-year leases on military bases and free trade privileges.

Between 1946 and 1972, the Philippines was governed according to a Constitution modeled after the American one. The fact that the United States kept its promise of independence to the Philippines after World War II put some pressure on the European to do the same in their colonies.

The Philippines After World War II

Demoralized by the war and suffering rampant inflation and shortages of food and other goods, the Philippine people prepared for the transition to independence, which was scheduled for July 4, 1946. A number of issues remained unresolved, principally those concerned with trade and security arrangements between the islands and the United States. Yet in the months following Japan's surrender, collaboration became a virulent issue that split the country and poisoned political life. Most of the commonwealth legislature and leaders, such as Laurel, Claro Recto, and Roxas, had served in the Japanese-sponsored government. While the war was still going on, Allied leaders had stated that such "quislings" and their counterparts on the provincial and local levels would be severely punished. Harold Ickes, who as United States secretary of the interior had civil authority over the islands, suggested that all officials above the rank of schoolteacher who had cooperated with the Japanese be purged and denied the right to vote in the first postwar elections. Osmeña countered that each case should be tried on its own merits. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Resolution of the problem posed serious moral questions that struck at the heart of the political system. Collaborators argued that they had gone along with the occupiers in order to shield the people from the harshest aspects of Japanese rule. Before leaving Corregidor in March 1942, Quezon had told Laurel and José Vargas, mayor of Manila, that they should stay behind to deal with the Japanese but refuse to take an oath of allegiance. Although president of a "puppet" republic, Laurel had faced down the Japanese several times and made it clear that his loyalty was first to the Philippines and second to the Japanese-sponsored Greater East Asia Coprosperity Sphere. *

Critics accused the collaborators of opportunism and of enriching themselves while the people starved. Anticollaborationist feeling, moreover, was fueled by the people's resentment of the elite. On both the local and the national levels, it had been primarily the landlords, important officials, and the political establishment that had supported the Japanese, largely because the latter, with their own troops and those of a reestablished Philippine Constabulary, preserved their property and forcibly maintained the rural status quo. Tenants felt the harshest aspects of Japanese rule. Guerrillas, particularly those associated with the Huks, came from the ranks of the cultivators, who organized to defend themselves against Philippine Constabulary and Japanese depredations. *

Manual Roxas Becomes President Despite Being Labeled a Collaborator

The issue of collaboration centered on Roxas, prewar Nacionalista speaker of the House of Representatives, who had served as minister without portfolio and was responsible for rice procurement and economic policy in the wartime Laurel government. A close prewar associate of MacArthur, he maintained contact with Allied intelligence during the war and in 1944 had unsuccessfully attempted to escape to Allied territory, which exonerated him in the general's eyes. [Source: Library of Congress *]

MacArthur supported Roxas in his ambitions for the presidency when he announced himself as a candidate of the newly formed Liberal Party (the liberal wing of the Nacionalista Party) in January 1946. MacArthur's favoritism aroused much criticism, particularly because other collaborationist leaders were held in jail, awaiting trial. A presidential campaign of great vindictiveness ensued, in which Roxas's wartime role was a central issue. Roxas outspent and outspoke his Nacionalista opponent, the aging and ailing Osmeña. In the April 23, 1946, election, Roxas won 54 percent of the vote, and the Liberal Party won a majority in the legislature. *

On July 4, 1946, Roxas became the first president of the independent Republic of the Philippines. In 1948 he declared an amnesty for arrested collaborators — only one of whom had been indicted — except for those who had committed violent crimes. The resiliency of the prewar elite, although remarkable, nevertheless had left a bitter residue in the minds of the people. In the first years of the republic, the issue of collaboration became closely entwined with old agrarian grievances and produced violent results. *

Independent, Democratic Philippines

Beginning with independence in 1946, the church was a source of stability to the infant nation. Throughout the period of constitutional government up to the declaration of martial law in 1972, however, the church remained outside of politics; its largely conservative clergy was occupied almost exclusively with religious matters. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Democracy functioned fairly well in the Philippines until 1972. National elections were held regularly under the framework of the 1935 constitution, which established checks and balances among the principal branches of government. Elections provided freewheeling, sometimes violent, exchanges between two loosely structured political parties, with one succeeding the other at the apex of power in a remarkably consistent cycle of alternation. Ferdinand Marcos, first elected to the presidency in 1965, was reelected by a large margin in 1969, the first president since independence to be elected to a second term. *

The economy remained highly dependent on U.S. markets, and the United States also continued to maintain control of 23 military installations. A bilateral treaty was signed in March 1947 by which the United States continued to provide military aid, training, and matériel. Such aid was timely, as the Huk guerrillas rose again, this time against the new government. They changed their name to the People’s Liberation Army (Hukbong Mapagpalaya ng Bayan) and demanded political participation, disbandment of the military police, and a general amnesty. Negotiations failed, and a rebellion began in 1950 with communist support. The aim was to overthrow the government. The Huk movement dissipated into criminal activities by 1951, as the better-trained and -equipped Philippine armed forces and conciliatory government moves toward the peasants offset the effectiveness of the Huks. *

Economic Relations with the United States after Philippines Independence

If the inauguration of the Commonwealth of the Philippines in November 1935 marked the high point of Philippine-United States relations, the actual achievement of independence was in many ways a disillusioning anticlimax. Economic relations remained the most salient issue. The Philippine economy remained highly dependent on United States markets — more dependent, according to United States high commissioner Paul McNutt, than any single state was dependent on the rest of the country. Thus a severance of special relations at independence was unthinkable, and large landowners, particularly those with hectarage in sugar, campaigned for an extension to free trade. The Philippine Trade Act, passed by the United States Congress in 1946 and commonly known as the Bell Act, stipulated that free trade be continued until 1954; thereafter, tariffs would be increased 5 percent annually until full amounts were reached in 1974. Quotas were established for Philippine products both for free trade and tariff periods. At the same time, there would be no restrictions on the entry of United States products to the Philippines, nor would there be Philippine import duties. The Philippine peso was tied at a fixed rate to the United States dollar. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The most controversial provision of the Bell Act was the "parity" clause that granted United States citizens equal economic rights with Filipinos, for example, in the exploitation of natural resources. If parity privileges of individuals or corporations were infringed upon, the president of the United States had the authority to revoke any aspect of the trade agreement. Payment of war damages amounting to US$620 million, as stipulated in the Philippine Rehabilitation Act of 1946, was made contingent on Philippine acceptance of the parity clause. *

The Bell Act was approved by the Philippine legislature on July 2, two days before independence. The parity clause, however, required an amendment relating to the 1935 constitution's thirteenth article, which reserved the exploitation of natural resources for Filipinos. This amendment could be obtained only with the approval of three-quarters of the members of the House and Senate and a plebiscite. The denial of seats in the House to six members of the leftist Democratic Alliance and three Nacionalistas on grounds of fraud and violent campaign tactics during the April 1946 election enabled Roxas to gain legislative approval on September 18. The definition of three-quarters became an issue because three-quarters of the sitting members, not the full House and Senate, had approved the amendment, but the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the administration's interpretation . *

In March 1947, a plebiscite on the amendment was held; only 40 percent of the electorate participated, but the majority of those approved the amendment. The Bell Act, particularly the parity clause, was seen by critics as an inexcusable surrender of national sovereignty. The pressure of the sugar barons, particularly those of Roxas's home region of the western Visayan Islands, and other landowner interests, however, was irresistible. In 1955 a revised United States-Philippine Trade Agreement (the Laurel-Langley Agreement) was negotiated. This treaty abolished the United States authority to control the exchange rate of the peso, made parity privileges reciprocal, extended the sugar quota, and extended the time period for the reduction of other quotas and for the progressive application of tariffs on Philippine goods exported to the United States. *

Security Agreements Between the Philippines and the United States