- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

The Founding Fathers Feared Political Factions Would Tear the Nation Apart

By: Sarah Pruitt

Updated: September 29, 2023 | Original: November 6, 2018

Today, it may seem impossible to imagine the U.S. government without its two leading political parties, Democrats and Republicans. But in 1787, when delegates to the Constitutional Convention gathered in Philadelphia to hash out the foundations of their new government, they entirely omitted political parties from the new nation’s founding document.

This was no accident. The framers of the new Constitution desperately wanted to avoid the divisions that had ripped England apart in the bloody civil wars of the 17th century . Many of them saw parties—or “factions,” as they called them—as corrupt relics of the monarchical British system that they wanted to discard in favor of a truly democratic government.

“It was not that they didn’t think of parties,” says Willard Sterne Randall, professor emeritus of history at Champlain College and biographer of six of the Founding Fathers. “Just the idea of a party brought back bitter memories to some of them.”

George Washington ’s family had fled England precisely to avoid the civil wars there, while Alexander Hamilton once called political parties “the most fatal disease” of popular governments. James Madison , who worked with Hamilton to defend the new Constitution to the public in the Federalist Papers, wrote in Federalist 10 that one of the functions of a “well-constructed Union” should be “its tendency to break and control the violence of faction.”

But Thomas Jefferson , who was serving a diplomatic post in France during the Constitutional Convention, believed it was a mistake not to provide for different political parties in the new government. “Men by their constitutions are naturally divided into two parties,’’ he would write in 1824 .

In fact, when Washington ran unopposed to win the first presidential election in the nation’s history, in 1789, he chose Jefferson for his Cabinet so it would be inclusive of differing political viewpoints. “I think he had been warned if he didn't have Jefferson in it, then Jefferson might oppose his government,” Randall says.

With Jefferson as secretary of state and Hamilton as Treasury secretary, two competing visions for America developed into the nation’s first two political parties. Supporters of Hamilton’s vision of a strong central government—many of whom were Northern businessmen, bankers and merchants who leaned toward England when it came to foreign affairs—would become known as the Federalists. Jefferson, on the other hand, favored limited federal government and keeping power in state and local hands. His supporters tended to be small farmers, artisans and Southern planters who traded with the French, and were sympathetic to France.

Though he had sided with Hamilton in their defense of the Constitution, Madison strongly opposed Hamilton’s ambitious financial programs, which he saw as concentrating too much power in the hands of the federal government. In 1791, Madison and Jefferson joined forces in forming what would become the Democratic-Republican Party (forerunner of today’s Democratic Party ) largely in response to Hamilton’s programs, including the federal government’s assumption of states’ debt and the establishment of a national banking system.

By the mid 1790s, Jefferson and Hamilton had both quit Washington’s Cabinet. Meanwhile, the Democratic-Republicans and Federalists spent much of the first president’s second term bitterly attacking each other in competing newspapers over their opinions of his administration’s policies.

When Washington stepped aside as president in 1796, he memorably warned in his farewell address of the divisive influence of factions on the workings of democracy: “The common and continual mischiefs of the spirit of party are sufficient to make it the interest and duty of a wise people to discourage and restrain it.”

“He had stayed on for a second term only to keep these two parties from warring with each other,” Randall says of Washington. “He was afraid of what he called ‘disunion.’ That if the parties flourished, and they kept fighting each other, that the Union would break up.”

By that time, however, the damage had been done. After the highly contentious election of 1796, when John Adams narrowly defeated Jefferson, the new president moved to squash opposition by making it a federal crime to criticize the president or his administration’s policies . Jefferson struck back in spades after toppling the unpopular Adams four years later, when Democratic-Republicans won control of both Congress and the presidency. “He fired half of all federal employees—the top half,” Randall explains. “He kept only the clerks and the customs agents, destroying the Federalist Party and making it impossible to rebuild.”

While the Federalists would never win another presidential election, and disappeared for good after the War of 1812, the two-party system revived itself with the rise of Andrew Jackson’s Democratic Party by the 1830s and firmly solidified in the 1850s, after the founding of the Republican Party . Though the parties’ identities and regional identifications would shift greatly over time, the two-party system we know today had fallen into place by 1860—even as the nation stood poised on the brink of the very civil war that Washington and the other Founding Fathers had desperately wanted to avoid.

HISTORY Vault: The American Revolution

Stream American Revolution documentaries and your favorite HISTORY series, commercial-free.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 3

- The Articles of Confederation

- What was the Articles of Confederation?

- Shays's Rebellion

- The Constitutional Convention

- The US Constitution

The Federalist Papers

- The Bill of Rights

- Social consequences of revolutionary ideals

- The presidency of George Washington

- Why was George Washington the first president?

- The presidency of John Adams

- Regional attitudes about slavery, 1754-1800

- Continuity and change in American society, 1754-1800

- Creating a nation

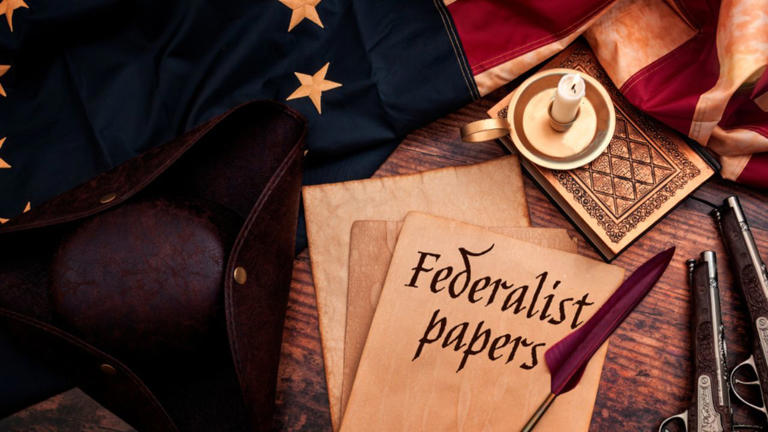

- The Federalist Papers was a collection of essays written by John Jay, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton in 1788.

- The essays urged the ratification of the United States Constitution, which had been debated and drafted at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787.

- The Federalist Papers is considered one of the most significant American contributions to the field of political philosophy and theory and is still widely considered to be the most authoritative source for determining the original intent of the framers of the US Constitution.

The Articles of Confederation and Constitutional Convention

- In Federalist No. 10 , Madison reflects on how to prevent rule by majority faction and advocates the expansion of the United States into a large, commercial republic.

- In Federalist No. 39 and Federalist 51 , Madison seeks to “lay a due foundation for that separate and distinct exercise of the different powers of government, which to a certain extent is admitted on all hands to be essential to the preservation of liberty,” emphasizing the need for checks and balances through the separation of powers into three branches of the federal government and the division of powers between the federal government and the states. 4

- In Federalist No. 84 , Hamilton advances the case against the Bill of Rights, expressing the fear that explicitly enumerated rights could too easily be construed as comprising the only rights to which American citizens were entitled.

What do you think?

- For more on Shays’s Rebellion, see Leonard L. Richards, Shays’s Rebellion: The American Revolution’s Final Battle (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002).

- Bernard Bailyn, ed. The Debate on the Constitution: Federalist and Anti-Federalist Speeches, Articles, and Letters During the Struggle over Ratification; Part One, September 1787 – February 1788 (New York: Penguin Books, 1993).

- See Federalist No. 1 .

- See Federalist No. 51 .

- For more, see Michael Meyerson, Liberty’s Blueprint: How Madison and Hamilton Wrote the Federalist Papers, Defined the Constitution, and Made Democracy Safe for the World (New York: Basic Books, 2008).

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

The Federalist Party

After the passage and ratification of the Constitution and subsequent Bill of Rights, the Legislative Branch began to resemble what it is today. While organized political parties were nonexistent during the presidency of George Washington , informal factions formed between congressmen that were either ‘Pro-Administration’ or ‘Anti-Administration’. After George Washington stepped down as President, the informal coalitions in Congress became officially organized, transforming the ‘Pro-Administration’ faction into the Federalist Party and the ‘Anti-Administration’ faction into the Jeffersonian Party (Also known as the Democratic-Republicans or Anti-Federalists).

The Federalist Party was formed by Alexander Hamilton , John Jay, and James Madison who all authored many of the Federalist Papers. Hamilton was a key ideological figure for this political party, influencing other party members with his previous experience as the Secretary of the Treasury under Washington. Thus, the party advocated for a stronger national government centered around the Executive Branch among other federal entities. The main base of support for this party came from the urban cities as well as the New England area. The supporters were of the mind that the national government was superior to the state government, thus establishing a governmental hierarchy.

The Federalist Party had many successes throughout the late 1700s in the Legislative Branch. In the Executive Branch, the second President of the United States, John Adams , was a member of the Federalist Party and was to be the only Federalist president in US history. Once the early 1800s arrived, the Federalists began to lose support among the American voters, allowing the rival Jeffersonian Party to garner support. The death of Hamilton at the hands of Aaron Burr and the final Federalist candidate for President losing in 1816 (Rufus King) marked the end of the Federalist Party. However, Supreme Court Chief Justice, and moderate Federalist, John Marshall continued the party’s legacy of federal supremacy long after the party’s dissolution.

DOMESTIC POLICIES:

The Federalist Party saw the Articles of Confederation as weak and indicative of the inevitable instability a nation will face without a strong centralized government. Thus, the party advocated heavily in favor of the Implied Powers of the President within the Constitution alongside Federal Supremacy. Despite fears of a tyrannical central figure, the Federalists maintained that the Constitution was to act as a safeguard in order to prevent a tyrant from taking power. The preventative measures for the federal government were to come in the form of checks and balances that were laid out in the Constitution, alongside other measures like Senate approval/ratification, Judicial Review, and Executive appointed positions. The Federalist Party in Congress passed the Naturalization Act of 1790 which provided citizenship for “free white person[s] ... of good character” who had been in the United States for a certain amount of time. This law was amended in 1798 to increase the minimum time one had to be a resident in the US from 5 years to 14 years. Furthermore, the law granted children of US citizens that were born abroad US citizenship. However, the Federalist’s most controversial domestic law put into place was the Sedition Act of 1798. The law, signed under President John Adams , allowed people who wrote “false, scandalous, or malicious writing” regarding the government to be imprisoned, fined, or even deported.

ECONOMIC POLICIES:

The Revolutionary War caused the Continental Congress to amass an incredible amount of war debt that was inherited by the new United States Government. Additionally, under the Articles of Confederation, the debt of individual states was unable to be collected by the federal government, resulting in more economic issues for the infant nation. Hamilton’s previous experience as Secretary of the Treasury heavily influenced the Federalist economic thought. Thus, the party’s policies reflected a focus on the national economy rather than that of individual states. The Federalist debt platform focused around import tariffs and taxation of shipping tonnage to gain revenue while protecting industries in the US to make the new nation self-sufficient. Additionally, the US government paid all state debts in order to give legitimacy to the national government. Hamilton managed to accomplish this by having investors invest in public securities, a type of bond that must be repaid-with interest, thus giving the federal government the money to be able to pay off the debt of each state. Furthermore, the public investment established credit between the national government and international and domestic investors. In addition to creating a strong line of public credit, the Federalist’s established the First National Bank in 1791 to ensure a safe and fair system of trading and exchanging securities through a stable national currency. James Madison contested that congress did not have the power to create a national bank and later sided with Thomas Jefferson and his party of Jeffersonians in opposition to these Federalist policies.

FOREIGN POLICIES:

Tensions between the United States and Britain were at an all-time high despite the Revolutionary War being over with the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783 . British forces remained in forts among the Great Lakes area, Canada was still ruled by the British Empire, captured American shipping vessels traveling from the British West Indies, and provided weapons to numerous Native American tribes, while the British government refused to clarify a solid border between the US and Canada, impressed American sailors for service in the British Navy against Revolutionary France , and never paid compensation for the slaves of Loyalist settlers, although the peace agreement stated otherwise. The Federalists, horrified at the actions of Revolutionary France, were keen on repairing and maintaining a stable relationship with Britain. To resolve this issue, Federalists promoted the ratification of the Jay Treaty . The treaty, negotiated by Supreme Court Justice John Jay, solidified the US-Canadian border, removed British military presence in the Great Lakes region, allowed American shipping to access portions of the British West Indies, and established a trading relationship between the US and Britain which included Anti-French trading practices. The Anti-French sentiments among the Federalists continued to grow. The Federalist President John Adams refused to repay war debts to Revolutionary France because of Adam’s belief that the debt was owed to the French Kingdom rather than the current regime. This act outraged the First French Republic who then refused to negotiate with American delegations without a bribe beforehand. This sparked the XYZ Affair which insulted the American government and resulted in the ‘Quasi-War’ with France which saw the back and forth capture of American and French shipping on seabound trade routes. Additionally, the Federalists passed the Alien Acts, which allowed the president to deport any foreign national that may threaten the peace and security of the US or any military-aged man of a hostile country. The acts of aggression angered those opposed to the Federalists and increased popular support for the Jeffersonians. Furthermore, the Federalists were staunchly opposed to the War of 1812 , which they titled “Mr. Madison’s War”. In some instances, certain Federalist areas refused to call up volunteers and militias to fight against the British. Federalist opposition to the War of 1812 was so widespread that many contend that the war was the United States’ most unpopular war.

Further Reading

- The Federalist Papers By: Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay

- Rights of Man By: Thomas Paine

The Treaty of Ghent: Ending the War of 1812

Battle of New Orleans: The Last Battle of the War of 1812

When Life Surrounds You With Death

Founders Online --> [ Back to normal view ]

The federalist number 10, [22 november] 1787, the federalist number 10.

[22 November 1787]

Among the numerous advantages promised by a well constructed union, none deserves to be more accurately developed than its tendency to break and control the violence of faction. 1 The friend of popular governments, never finds himself so much alarmed for their character and fate, as when he contemplates their propensity to this dangerous vice. He will not fail therefore to set a due value on any plan which, without violating the principles to which he is attached, provides a proper cure for it. The instability, injustice and confusion introduced into the public councils, have in truth been the mortal diseases under which popular governments have every where perished; as they continue to be the favorite and fruitful topics from which the adversaries to liberty derive their most specious declamations. The valuable improvements made by the American constitutions on the popular models, both antient and modern, cannot certainly be too much admired; but it would be an unwarrantable partiality, to contend that they have as effectually obviated the danger on this side as was wished and expected. Complaints are every where heard from our most considerate and virtuous citizens, equally the friends of public and private faith, and of public and personal liberty; that our governments are too unstable; that the public good is disregarded in the conflicts of rival parties; and that measures are too often decided, not according to the rules of justice, and the rights of the minor party; but by the superior force of an interested and over-bearing majority. However anxiously we may wish that these complaints had no foundation, the evidence of known facts will not permit us to deny that they are in some degree true. It will be found indeed, on a candid review of our situation, that some of the distresses under which we labour, have been erroneously charged on the operation of our governments; but it will be found at the same time, that other causes will not alone account for many of our heaviest misfortunes; and particularly, for that prevailing and increasing distrust of public engagements, and alarm for private rights, which are echoed from one end of the continent to the other. These must be chiefly, if not wholly, effects of the unsteadiness and injustice, with which a factious spirit has tainted our public administration.

By a faction I understand a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adverse to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community.

There are two methods of curing the mischiefs of faction: The one, by removing its causes; the other, by controlling its effects.

There are again two methods of removing the causes of faction: The one by destroying the liberty which is essential to its existence; the other, by giving to every citizen the same opinions, the same passions, and the same interests.

It could never be more truly said than of the first remedy, that it is worse than the disease. Liberty is to faction, what air is to fire, an aliment without which it instantly expires. But it could not be a less folly to abolish liberty, which is essential to political life, because it nourishes faction, than it would be to wish the annihilation of air, which is essential to animal life because it imparts to fire its destructive agency.

The second expedient is as impracticable, as the first would be unwise. As long as the reason of man continues fallible, and he is at liberty to exercise it, different opinions will be formed. As long as the connection subsists between his reason and his self-love, his opinions and his passions will have a reciprocal influence on each other; and the former will be objects to which the latter will attach themselves. The diversity in the faculties of men from which the rights of property originate, is not less an insuperable obstacle to an uniformity of interests. The protection of these faculties is the first object of government. From the protection of different and unequal faculties of acquiring property, the possession of different degrees and kinds of property immediately results: And from the influence of these on the sentiments and views of the respective proprietors, ensues a division of the society into different interests and parties.

The latent causes of faction are thus sown in the nature of man; and we see them every where brought into different degrees of activity, according to the different circumstances of civil society. A zeal for different opinions concerning religion, concerning government, and many other points, as well of speculation as of practice; an attachment to different leaders ambitiously contending for pre-eminence and power; or to persons of other descriptions whose fortunes have been interesting to the human passions, have in turn divided mankind into parties, inflamed them with mutual animosity, and rendered them much more disposed to vex and oppress each other, than to co-operate for their common good. So strong is this propensity of mankind to fall into mutual animosities, that where no substantial occasion presents itself, the most frivolous and fanciful distinctions have been sufficient to kindle their unfriendly passions, and excite their most violent conflicts. But the most common and durable source of factions, has been the various and unequal distribution of property. Those who hold, and those who are without property, have ever formed distinct interests in society. Those who are creditors, and those who are debtors, fall under a like discrimination. A landed interest, a manufacturing interest, a mercantile interest, a monied interest, with many lesser interests, grow up of necessity in civilized nations, and divide them into different classes, actuated by different sentiments and views. The regulation of these various and interfering interests forms the principal task of modern legislation, and involves the spirit of party and faction in the necessary and ordinary operations of government.

No man is allowed to be a judge in his own cause; because his interest would certainly bias his judgment, and, not improbably, corrupt his integrity. With equal, nay with greater reason, a body of men, are unfit to be both judges and parties, at the same time; yet, what are many of the most important acts of legislation, but so many judicial determinations, not indeed concerning the rights of single persons, but concerning the rights of large bodies of citizens; and what are the different classes of legislators, but advocates and parties to the causes which they determine? Is a law proposed concerning private debts? It is a question to which the creditors are parties on one side, and the debtors on the other. Justice ought to hold the balance between them. Yet the parties are and must be themselves the judges; and the most numerous party, or, in other words, the most powerful faction must be expected to prevail. Shall domestic manufactures be encouraged, and in what degree, by restrictions on foreign manufactures? are questions which would be differently decided by the landed and the manufacturing classes; and probably by neither, with a sole regard to justice and the public good. The apportionment of taxes on the various descriptions of property, is an act which seems to require the most exact impartiality, yet there is perhaps no legislative act in which greater opportunity and temptation are given to a predominant party, to trample on the rules of justice. Every shilling with which they over-burden the inferior number, is a shilling saved to their own pockets.

It is in vain to say, that enlightened statesmen will be able to adjust these clashing interests, and render them all subservient to the public good. Enlightened statesmen will not always be at the helm: Nor, in many cases, can such an adjustment be made at all, without taking into view indirect and remote considerations, which will rarely prevail over the immediate interest which one party may find in disregarding the rights of another, or the good of the whole.

The inference to which we are brought, is, that the causes of faction cannot be removed; and that relief is only to be sought in the means of controlling its effects .

If a faction consists of less than a majority, relief is supplied by the republican principle, which enables the majority to defeat its sinister views by regular vote: It may clog the administration, it may convulse the society; but it will be unable to execute and mask its violence under the forms of the constitution. When a majority is included in a faction, the form of popular government on the other hand enables it to sacrifice to its ruling passion or interest, both the public good and the rights of other citizens. To secure the public good, and private rights against the danger of such a faction, and at the same time to preserve the spirit and the form of popular government, is then the great object to which our enquiries are directed. Let me add that it is the great desideratum, by which alone this form of government can be rescued from the opprobrium under which it has so long labored, and be recommended to the esteem and adoption of mankind.

By what means is this object attainable? Evidently by one of two only. Either the existence of the same passion or interest in a majority at the same time, must be prevented; or the majority, having such co-existent passion or interest, must be rendered, by their number and local situation, unable to concert and carry into effect schemes of oppression. If the impulse and the opportunity be suffered to coincide, we well know that neither moral nor religious motives can be relied on as an adequate control. They are not found to be such on the injustice and violence of individuals, and lose their efficacy in proportion to the number combined together; that is, in proportion as their efficacy becomes needful. 2

From this view of the subject, it may be concluded that a pure democracy, by which I mean a society, consisting of a small number of citizens, who assemble and administer the government in person, can admit of no cure for the mischiefs of faction. A common passion or interest will, in almost every case, be felt by a majority of the whole; a communication and concert results from the form of government itself; and there is nothing to check the inducements to sacrifice the weaker party, or an obnoxious individual. Hence it is, that such democracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention; have ever been found incompatible with personal security, or the rights of property; and have in general been as short in their lives, as they have been violent in their deaths. Theoretic politicians, who have patronized this species of government, have erroneously supposed, that by reducing mankind to a perfect equality in their political rights, they would, at the same time, be perfectly equalized, and assimilated in their possessions, their opinions, and their passions.

A republic, by which I mean a government in which the scheme of representation takes place, opens a different prospect, and promises the cure for which we are seeking. Let us examine the points in which it varies from pure democracy, and we shall comprehend both the nature of the cure, and the efficacy which it must derive from the union.

The two great points of difference between a democracy and a republic, are first, the delegation of the government, in the latter, to a small number of citizens elected by the rest; secondly, the greater number of citizens, and greater sphere of country, over which the latter may be extended.

The effect of the first difference is, on the one hand, to refine and enlarge the public views, by passing them through the medium of a chosen body of citizens, whose wisdom may best discern the true interest of their country, and whose patriotism and love of justice, will be least likely to sacrifice it to temporary or partial considerations. Under such a regulation, it may well happen that the public voice pronounced by the representatives of the people, will be more consonant to the public good, than if pronounced by the people themselves convened for the purpose. On the other hand, the effect may be inverted. Men of factious tempers, of local prejudices, or of sinister designs, may by intrigue, by corruption, or by other means, first obtain the suffrages, and then betray the interests of the people. The question resulting is, whether small or extensive republics are most favourable to the election of proper guardians of the public weal; and it is clearly decided in favour of the latter by two obvious considerations.

In the first place it is to be remarked, that however small the republic may be, the representatives must be raised to a certain number, in order to guard against the cabals of a few; and that however large it may be, they must be limited to a certain number, in order to guard against the confusion of a multitude. Hence the number of representatives in the two cases not being in proportion to that of the constituents, and being proportionally greatest in the small republic, it follows, that if the proportion of fit characters be not less in the large than in the small republic, the former will present a greater option, and consequently a greater probability of a fit choice.

In the next place, as each representative will be chosen by a greater number of citizens in the large than in the small republic, it will be more difficult for unworthy candidates to practise with success the vicious arts, by which elections are too often carried; and the suffrages of the people being more free, will be more likely to centre on men who possess the most attractive merit, and the most diffusive and established characters.

It must be confessed, that in this, as in most other cases, there is a mean, on both sides of which inconveniencies will be found to lie. By enlarging too much the number of electors, you render the representative too little acquainted with all their local circumstances and lesser interests; as by reducing it too much, you render him unduly attached to these, and too little fit to comprehend and pursue great and national objects. The federal constitution forms a happy combination in this respect; the great and aggregate interests being referred to the national, the local and particular to the state legislatures.

The other point of difference is, the greater number of citizens and extent of territory which may be brought within the compass of republican, than of democratic government; and it is this circumstance principally which renders factious combinations less to be dreaded in the former, than in the latter. The smaller the society, the fewer probably will be the distinct parties and interests composing it; the fewer the distinct parties and interests, the more frequently will a majority be found of the same party; and the smaller the number of individuals composing a majority, and the smaller the compass within which they are placed, the more easily will they concert and execute their plans of oppression. Extend the sphere, and you take in a greater variety of parties and interests; you make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens; or if such a common motive exists, it will be more difficult for all who feel it to discover their own strength, and to act in unison with each other. Besides other impediments, it may be remarked, that where there is a consciousness of unjust or dishonourable purposes, communication is always checked by distrust, in proportion to the number whose concurrence is necessary.

Hence it clearly appears, that the same advantage, which a republic has over a democracy, in controlling the effects of faction, is enjoyed by a large over a small republic—is enjoyed by the union over the states composing it. Does this advantage consist in the substitution of representatives, whose enlightened views and virtuous sentiments render them superior to local prejudices, and to schemes of injustice? It will not be denied, that the representation of the union will be most likely to possess these requisite endowments. Does it consist in the greater security afforded by a greater variety of parties, against the event of any one party being able to outnumber and oppress the rest? In an equal degree does the encreased variety of parties, comprised within the union, encrease this security. Does it, in fine, consist in the greater obstacles opposed to the concert and accomplishment of the secret wishes of an unjust and interested majority? Here, again, the extent of the union gives it the most palpable advantage.

The influence of factious leaders may kindle a flame within their particular states, but will be unable to spread a general conflagration through the other states: A religious sect, may degenerate into a political faction in a part of the confederacy; but the variety of sects dispersed over the entire face of it, must secure the national councils against any danger from that source: A rage for paper money, for an abolition of debts, for an equal division of property, or for any other improper or wicked project, will be less apt to pervade the whole body of the union, than a particular member of it; in the same proportion as such a malady is more likely to taint a particular county or district, than an entire state. 3

In the extent and proper structure of the union, therefore, we behold a republican remedy for the diseases most incident to republican government. And according to the degree of pleasure and pride, we feel in being republicans, ought to be our zeal in cherishing the spirit, and supporting the character of federalists.

McLean description begins The Federalist, A Collection of Essays, written in favour of the New Constitution, By a Citizen of New-York. Printed by J. and A. McLean (New York, 1788). description ends , I, 52–61.

1 . Douglass Adair showed chat in preparing this essay, especially that part containing the analysis of factions and the theory of the extended republic, JM creatively adapted the ideas of David Hume (“‘That Politics May Be Reduced to a Science’: David Hume, James Madison, and the Tenth Federalist,” Huntington Library Quarterly , XX [1956–57], 343–60). The forerunner of The Federalist No. 10 may be found in JM’s Vices of the Political System ( PJM description begins William T. Hutchinson et al., eds., The Papers of James Madison (10 vols. to date; Chicago, 1962——). description ends , IX, 348–57 ). See also JM’s first speech of 6 June and his first speech of 26 June 1787 at the Federal Convention, and his letter to Jefferson of 24 Oct. 1787 .

2 . In Vices of the Political System JM listed three motives, each of which he believed was insufficient to prevent individuals or factions from oppressing each other: (1) “a prudent regard to their own good as involved in the general and permanent good of the Community”; (2) “respect for character”; and (3) religion. As to “respect for character,” JM remarked that “in a multitude its efficacy is diminished in proportion to the number which is to share the praise or the blame” ( PJM description begins William T. Hutchinson et al., eds., The Papers of James Madison (10 vols. to date; Chicago, 1962——). description ends , IX, 355–56 ). For this observation JM again drew upon David Hume. Adair suggests that JM deliberately omitted his list of motives from The Federalist . “There was a certain disadvantage in making derogatory remarks to a majority that must be persuaded to adopt your arguments” (“‘That Politics May Be Reduced to a Science,’” Huntington Library Quarterly , XX [1956–57], 354). JM repeated these motives in his first speech of 6 June 1787, in his letter to Jefferson of 24 Oct. 1787 , and alluded to them in The Federalist No. 51 .

3 . The negative on state laws, which JM had unsuccessfully advocated at the Federal Convention, was designed to prevent the enactment of “improper or wicked” measures by the states. The Constitution did include specific prohibitions on the state legislatures, but JM dismissed these as “short of the mark.” He also doubted that the judicial system would effectively “keep the States within their proper limits” ( JM to Jefferson, 24 Oct. 1787 ).

Index Entries

You are looking at.

Explore the Constitution

- The Constitution

- Read the Full Text

Dive Deeper

Constitution 101 course.

- The Drafting Table

- Supreme Court Cases Library

- Founders' Library

- Constitutional Rights: Origins & Travels

Start your constitutional learning journey

- News & Debate Overview

- Constitution Daily Blog

- America's Town Hall Programs

- Special Projects

Media Library

America’s Town Hall

Watch videos of recent programs.

- Education Overview

Constitution 101 Curriculum

- Classroom Resources by Topic

- Classroom Resources Library

- Live Online Events

- Professional Learning Opportunities

- Constitution Day Resources

Explore our new 15-unit high school curriculum.

- Explore the Museum

- Plan Your Visit

- Exhibits & Programs

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Host Your Event

- Buy Tickets

New exhibit

The first amendment, constitution 101 resources, 3.5 primary source: federalist no. 10 and federalist no. 55.

This activity is part of Module 3: Road to the Convention from the Constitution 101 Curriculum.

Federalist No. 10 View the document on the National Constitution Center’s website here .

After the Constitutional Convention adjourned in September 1787, heated debate on the merits of the Constitution followed. Each state was required to vote on the ratification of the document. A series of articles signed by “Publius” appeared in New York newspapers. These Federalist Papers supported the Constitution and continued to appear through the summer of 1788. Alexander Hamilton organized them, and he and Madison wrote most of the series of 85 articles, with John Jay contributing five. These essays were read and debated, especially in New York, which included many critics of the Constitution. The Federalist Papers have since taken on immense significance, as they have come to be seen as an important early exposition on the Constitution’s meaning. In Federalist 10, Madison explores how the Constitution combats the problem of faction.

A good government will counteract the dangers of faction. Among the numerous advantages promised by a well-constructed Union, none deserves to be more accurately developed than its tendency to break and control the violence of faction. The friend of popular governments never finds himself so much alarmed for their character and fate, as when he contemplates their propensity to this dangerous vice.

Our state constitutions improved on those that came before them, but they still have problems; they are unstable; and they often value factional interests over the common good. The valuable improvements made by the American constitutions on the popular models, both ancient and modern, cannot certainly be too much admired; but it would be an unwarranted partiality, to contend that they have as effectually obviated the danger on this side, as was wished and expected. Complaints are everywhere heard from our most considerate and virtuous citizens, equally the friends of public and private faith, and of public and personal liberty, that our governments are too unstable; that the public good is disregarded in the conflicts of rival parties; and that measures are too often decided, not according to the rules of justice, and the rights of the minor party, but by the superior force of an interested and overbearing majority. These must be chiefly, if not wholly, effects of the unsteadiness and injustice, with which a factious spirit has tainted our public administrations.

Factions are driven by passion and self-interest, not reason and the common good. By a faction, I understand a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adverse to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community.

But there are ways to tame the dangers of faction. There are two methods of curing the mischiefs of faction. The one, by removing its causes; the other, by controlling its effects. There are again two methods of removing the causes of faction. The one, by destroying the liberty which is essential to its existence; the other, by giving to every citizen the same opinions, the same passions, and the same interests.

One way is to take away everyone’s liberty; this is a bad idea. It could never be more truly said, than of the first remedy, that it is worse than the disease. Liberty is to faction what air is to fire, an aliment without which it instantly expires. But it would not be a less folly to abolish liberty, which is essential to political life because it nourishes faction, than it would be to wish the annihilation of air, which is essential to animal life, because it imparts to fire its destructive agency.

Another way is to give everyone the same opinions, passions, and interests; this isn’t possible in a free and diverse republic. The second expedient is as impracticable, as the first would be unwise. As long as the reason of man continues fallible, and he is at liberty to exercise it, different opinions will be formed. As long as the connection subsists between his reason and his selflove, his opinions and his passions will have a reciprocal influence on each other; and the former will be objects to which the latter will attach themselves. The diversity in the faculties of men, from which the rights of property originate, is not less an insuperable obstacle to an uniformity of interests. The protection of those faculties is the first object of government. From the protection of different and unequal faculties of acquiring property, the possession of different degrees and kinds of property immediately results; and from the influence of these on the sentiments and views of the respective proprietors, ensues a division of the society into different interests and parties.

Factions are natural, and they form easily; the most common cause is the unequal division of property. The latent causes of faction are thus sown in the nature of man; … and rendered them much more disposed to vex and oppress each other, than to co-operate for their common good. So strong is this propensity of mankind, to fall into mutual animosities, that where no substantial occasion presents itself, the most frivolous and fanciful distinctions have been sufficient to kindle their unfriendly passions and excite their most violent conflicts. But the most common and durable source of factions has been the various and unequal distribution of property. Those, who hold, and those who are without property, have ever formed distinct interests in society. Those who are creditors, and those who are debtors, fall into a like discrimination. A landed interest, a manufacturing interest, a mercantile interest, a moneyed interest, with many lesser interests, grow up of necessity in civilized nations, and divide them into different classes, actuated by different sentiments and views. The regulation of these various and interfering interests forms the principal task of modern legislation and involves the spirit of the party and faction in the necessary and ordinary operations of government.

We can’t rely on great leaders; we won’t always have them. It is vain to say, that enlightened statesmen will be able to adjust these clashing interests and render them all subservient to the public good. Enlightened statesmen will not always be at the helm.

We can’t eliminate the causes of faction; so, we must figure out how to control them. The inference to which we are brought is, that the causes of faction cannot be removed; and that relief is only to be sought in the means of controlling its effects.

Majority rule solves the problem of minority factions; we can vote abusive minority factions out of power; but this doesn’t solve the problem of a majority faction abusing the minority; we need to come up with a new solution to this vexing problem. If a faction consists of less than a majority, relief is supplied by the republican principle, which enables the majority to defeat its sinister views, by regular vote. It may clog the administration; it may convulse the society; but it will be unable to execute and mask its violence under the forms of the constitution. When a majority is included in a faction, the form of popular government, on the other hand, enables it to sacrifice to its ruling passion or interest, both the public good and the rights of other citizens. To secure the public good, and private rights, against the danger of such a faction, and at the same time to preserve the spirit and the form of popular government, is the greatest object to which our inquiries are directed. …

There are a couple of ways to address this problem. By what means is the object attainable? Evidently by one of two only. Either the existence of the same passion or interest in a majority, at the same time must be prevented; or the majority, having such coexistent passion or interest, must be rendered, by their number and local situation, unable to concert and carry into effect schemes of oppression.

Direct democracy isn’t the answer. From this view of the subject, it may be concluded, that a pure democracy, by which I mean a society consisting of a small number of citizens, who assemble and administer the government in person, can admit of no cure from the mischiefs of faction.

But representative government offers a promising path; to address the problem of faction, we need to elect representatives, and we need a large (not small) republic. A republic, by which I mean a government in which the scheme of representation takes place, opens a different prospect, and promises the cure for which we are seeking. Let us examine the points in which it varies from pure democracy, and we shall comprehend both the nature of the cure and the efficacy which it must derive from the union. The two great points of difference, between a democracy and a republic, are, first, the delegation of the government, in the latter, to a small number of citizens elected by the rest; secondly, the greater number of citizens, and the greater sphere of country, over which the latter may be extended.

Representative government promotes a process of deliberation led by virtuous leaders; this process improves public opinion and helps to ensure that we end up with a government that serves the common good, not the immediate passions of the people or the self-interests of powerful factions; finally, contrary to the views of famous political thinkers like Montesquieu, it is helpful that we have a large republic rather than a small one. The effect of the first difference is, on the one hand, to refine and enlarge the public views, by passing them through the medium of a chosen body of citizens, whose wisdom may best discern the true interest of their country, and whose patriotism and love of justice, will be least likely to sacrifice it to temporary or partial considerations. Under such a regulation, it may well happen, that the public voice, pronounced by the representatives of the people, will be more consonant to the public good, than if pronounced by the people themselves, convened for the purpose.... The question resulting is, whether small or extensive republics are most favorable to the election of proper guardians of the public weal; and it is clearly decided in favor of the latter by two obvious considerations.

There are a larger number of quality candidates in a large republic. In the first place, it is to be remarked, that however small the republic may be, the representatives must be raised to a certain number, in order to guard against the cabals of a few; and that however large it may be, they must be limited to a certain number, in order to guard against the confusion of a multitude. Hence, the number of representatives in the two cases not being in proportion to that of the constituents, and being proportionately greatest in the small republic, it follows that if the proportion of fit characters be not less in the large than in the small republic, the former will present a greater probability of a fit choice.

And in a large republic, the people are more likely to choose virtuous leaders than demagogues. In the next place, as each representative will be chosen by a greater number of citizens in the large than in the small republic, it will be more difficult for unworthy candidates to practice with success the vicious arts, by which elections are too often carried; and the suffrages of the people being more free, will be more likely to center in men who possess the most attractive merit, and the most diffusive and established characters.

Because a large republic covers more territory and contains a greater number of factions, it is more difficult for a majority faction to form and abuse power. The other point of difference is, the greater number of citizens, and extent of territory, which may be brought within the compass of republican, than of democratic government; and it is this circumstance principally which renders factious combinations less to be dreaded in the former, than in the latter. .. Extend the sphere, and you will take in a greater variety of parties and interests; you make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens; or if such common motive exists, it will be more difficult for all who feel it to discover their own strength, and to act in unison with each other.

Large republics are better at controlling faction than small republics. Hence, it clearly appears, that the same advantage, which a republic has over a democracy, in controlling the effects of faction, is enjoyed by a large over a small republic - enjoyed by the union over the states composing it.

We have found a republican solution to the problem of faction. In the extent and proper structure of the union, therefore, we behold a republican remedy for the diseases most incident to republican government.

Federalist No. 55 View the document on the National Constitution Center’s website here .

On February 15, 1788, James Madison published Federalist No. 55—titled “The Total Number of the House of Representatives.” Following Shays’ Rebellion in Massachusetts, Madison and his allies pushed for a new Constitution that might address the dangers of excessive democracy, including mob violence. In Federalist No. 55, Madison addressed a range of important issues, including the proper size of the House of Representatives, the role of representation in a republican government, and the importance of civic republican virtue. Madison warned, “In all very numerous assemblies, of whatever character composed, passion never fails to wrest the sceptre from reason. Had every Athenian citizen been a Socrates, every Athenian assembly would still have been a mob.” Madison had in mind a specific episode in ancient history—the push by the demagogue Cleon to mislead the massive Athenian Assembly (filled with 6,000 people) into starting the Peloponnesian War. With the new Constitution, the framers sought to create a new government strong enough to achieve common purpose and curb mob violence, but also restrained enough that it would not threaten individual rights.

Critics fear that the U.S. House of Representatives is too small to represent the interests of a large country; instead, there’s a danger that it will be filled with a small governing elite distant from the people. The number of which the House of Representatives is to consist, forms another and a very interesting point of view, under which this branch of the federal legislature may be contemplated. Scarce any article, indeed, in the whole Constitution seems to be rendered more worthy of attention, by the weight of character and the apparent force of argument with which it has been assailed. The charges exhibited against it are, first, that so small a number of representatives will be an unsafe depositary of the public interests; secondly, that they will not possess a proper knowledge of the local circumstances of their numerous constituents; thirdly, that they will be taken from that class of citizens which will sympathize least with the feelings of the mass of the people, and be most likely to aim at a permanent elevation of the few on the depression of the many; fourthly, that defective as the number will be in the first instance, it will be more and more disproportionate, by the increase of the people, and the obstacles which will prevent a correspondent increase of the representatives.

There is no right answer to how large a legislative body should be in order to govern well; this is a difficult issue, and the states themselves disagree over it. In general it may be remarked on this subject, that no political problem is less susceptible of a precise solution than that which relates to the number most convenient for a representative legislature; nor is there any point on which the policy of the several States is more at variance, whether we compare their legislative assemblies directly with each other, or consider the proportions which they respectively bear to the number of their constituents. . . .

There are also serious dangers when a legislative body is too large; this may undermine deliberation and heighten the passions; in the end, the goal is to try to avoid a body that is either too small or too large. Another general remark to be made is, that the ratio between the representatives and the people ought not to be the same where the latter are very numerous as where they are very few. Were the representatives in Virginia to be regulated by the standard in Rhode Island, they would, at this time, amount to between four and five hundred; and twenty or thirty years hence, to a thousand. On the other hand, the ratio of Pennsylvania, if applied to the State of Delaware, would reduce the representative assembly of the latter to seven or eight members. Nothing can be more fallacious than to found our political calculations on arithmetical principles. Sixty or seventy men may be more properly trusted with a given degree of power than six or seven. But it does not follow that six or seven hundred would be proportionably a better depositary. And if we carry on the supposition to six or seven thousand, the whole reasoning ought to be reversed. The truth is, that in all cases a certain number at least seems to be necessary to secure the benefits of free consultation and discussion, and to guard against too easy a combination for improper purposes; as, on the other hand, the number ought at most to be kept within a certain limit, in order to avoid the confusion and intemperance of a multitude. In all very numerous assemblies, of whatever character composed, passion never fails to wrest the sceptre from reason. Had every Athenian citizen been a Socrates, every Athenian assembly would still have been a mob. . . .

Elections are an important check on abuses by elected officials. The true question to be decided then is, whether the smallness of the number, as a temporary regulation, be dangerous to the public liberty? Whether sixty-five members for a few years, and a hundred or two hundred for a few more, be a safe depositary for a limited and well-guarded power of legislating for the United States? I must own that I could not give a negative answer to this question, without first obliterating every impression which I have received with regard to the present genius of the people of America, the spirit which actuates the State legislatures, and the principles which are incorporated with the political character of every class of citizens I am unable to conceive that the people of America, in their present temper, or under any circumstances which can speedily happen, will choose, and every second year repeat the choice of, sixty-five or a hundred men who would be disposed to form and pursue a scheme of tyranny or treachery. . . .

The critics of the Constitution are too pessimistic; the American people have enough virtue to make our new republic work. The improbability of such a mercenary and perfidious combination of the several members of government, standing on as different foundations as republican principles will well admit, and at the same time accountable to the society over which they are placed, ought alone to quiet this apprehension. But, fortunately, the Constitution has provided a still further safeguard. The members of the Congress are rendered ineligible to any civil offices that may be created, or of which the emoluments may be increased, during the term of their election. No offices therefore can be dealt out to the existing members but such as may become vacant by ordinary casualties: and to suppose that these would be sufficient to purchase the guardians of the people, selected by the people themselves, is to renounce every rule by which events ought to be calculated, and to substitute an indiscriminate and unbounded jealousy, with which all reasoning must be vain. The sincere friends of liberty, who give themselves up to the extravagancies of this passion, are not aware of the injury they do their own cause. As there is a degree of depravity in mankind which requires a certain degree of circumspection and distrust, so there are other qualities in human nature which justify a certain portion of esteem and confidence. Republican government presupposes the existence of these qualities in a higher degree than any other form. Were the pictures which have been drawn by the political jealousy of some among us faithful likenesses of the human character, the inference would be, that there is not sufficient virtue among men for self-government; and that nothing less than the chains of despotism can restrain them from destroying and devouring one another.

*Bold sentences give the big idea of the excerpt and are not a part of the primary source.

More from the National Constitution Center

Constitution 101

Explore our new 15-unit core curriculum with educational videos, primary texts, and more.

Search and browse videos, podcasts, and blog posts on constitutional topics.

Founders’ Library

Discover primary texts and historical documents that span American history and have shaped the American constitutional tradition.

Modal title

Modal body text goes here.

Share with Students

Federalists and Anti-Federalists

The Federalist and Anti-Federalist factions developed during the Constitutional Convention of 1787.

Alexander Hamilton was a prominent leader of the Federalist faction. Image Source: Wikipedia.

Federalists and Anti-Federalists Summary

The Federalists and Anti-Federalists were two factions that emerged in American politics during the Philadelphia Convention of 1787 . The original purpose of the Convention was to discuss problems with the government under the Articles of Confederation and find reasonable solutions. Instead of updating the Articles, the delegates replaced the Articles with something entirely new — the Constitution of the United States. Despite the development of the Constitution, there was disagreement. The people who favored the Constitution became known as Federalists. Those who disagreed, or even opposed it, were called Anti-Federalists. Anti-Federalists argued the Constitution failed to provide details regarding basic civil rights — a Bill of Rights — while Federalists argued the Constitution provided significant protection for individual rights. After the Constitution was adopted by the Convention, it was sent to the individual states for ratification. The ensuing debate between the Federalists and Anti-Federalists that followed remains of the great debates in American history, and eventually led to the ratification of the United States Constitution.

Quick Facts About Federalists

- The name “Federalists” was adopted by people who supported the ratification of the new United States Constitution.

- Federalists favored a strong central government and believed the Constitution provided adequate protection for individual rights.

- The group was primarily made up of large property owners, merchants, and businessmen, along with the clergy, and others who favored consistent law and order throughout the states.

- Prominent Federalists were James Madison , Alexander Hamilton , and John Jay .

- During the debate on the Constitution, the Federalists published a series of articles known as the “Federalists Papers” that argued for the passage of the Constitution.

- The Federalists eventually formed the Federalist Party in 1791 .

Quick Facts About Anti-Federalists

- Anti-Federalists had concerns about a central government that had too much power.

- They favored the system of government under the Articles of Confederation but were adamant the Constitution needed a defined Bill of Rights.

- The Anti-Federalists were typically small farmers, landowners, independent shopkeepers, and laborers.

- Prominent Anti-Federalists were Patrick Henry , Melancton Smith, Robert Yates, George Clinton , Samuel Bryan, and Richard Henry Lee .

- The Anti-Federalists delivered speeches and wrote pamphlets that explained their positions on the Constitution. The pamphlets are collectively known as the “Anti-Federalist Papers.”

- The Anti-Federalists formed the Democratic-Republican Party in 1792 .

Significance of Federalists and Anti-Federalists

The Federalists and Anti-Federalists are important to the history of the United States because their differences over the United States Constitution led to its ratification and the adoption of the Bill of Rights — the first 10 Amendments .

Learn More About Federalists and Anti-Federalists on American History Central

- Federalist No. 1

- Federalist No. 2

- Federalist No. 3

- Alexander Hamilton’s Speech to the New York Convention

- Articles of Confederation

- Presidency of George Washington — Study Guide

- Written by Randal Rust

Political Parties

Last Updated: 2006

Author: Peter N. Ubertaccio III

For most of American history, political parties have been shaped by the decentralized nature of the American political system. Unlike political parties in unitary systems, American parties have traditionally been weak organizations on the national level, reflecting the relatively weak state of the national government for much of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Political parties grew in stature on the national level as the federal system changed to reflect national power and administration. Yet the party system has always been rooted in the localized polity of American political history.

Contents[ hide ]

- 1 EARLY DEVELOPMENTS

- 2 A PARTY SYSTEM AS A FORCE FOR DECENTRALIZATION

- 3.1Peter N. Ubertaccio III

EARLY DEVELOPMENTS

Political parties in the United States did not develop easily. The Constitution was a reflection of James Madison’s understanding of factionalism in The Federalist No. 10. Madison understood factions to be “a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adverse to the rights of other citizens ,” and laid out a series of steps to protect the early republic from the threat of factions. The end result was the Constitution’s system of separation of powers, checks and balances, and federalism , all of which made it difficult for strong parties to form and operate. Unitary and nationalized systems of government tend to also be “party” governments: whichever party wins a majority in the legislature, or whichever parties can form a coalition, elects the government. Political parties as collective organizations are paramount in a parliamentary structure. Because the framers of the American constitution created a system that was hallmarked by federalism and the separation of powers, there were multiple centers of power in the United States and numerous institutional barriers to strong party organizations. Political parties would struggle for supremacy and would often fall short. Still, the very spirit that animated Madison’s theories would serve as the springboard for the early party system.

The Republican Party, the early and direct ancestor of the modern Democratic Party, organized around opposition to the administration of President George Washington and its perceived pro-British tilt, symbolized in the Jay Treaty, and the economic policies of Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton . Hamilton was a firm believer in a nationalized polity and strove to create a commercial republic in the United States. The Republican Party challenged Hamilton’s plans, and the 1796 presidential election saw this new organization—spearheaded by James Madison, Thomas Jefferson , and Philip Freneau—coordinate their efforts to defeat party members who supported the Jay Treaty. The Federalist Party, based largely in New England, defended Hamilton’s nationalist policies. The beginnings of a two-party system were thus created.

Thomas Jefferson used the organizational capacity of the Republican Party to enact key pieces of his legislative agenda in the aftermath of his election in 1800. Jefferson used the “spoils system,” or staffing public offices with political supporters, and party discipline to support and punish party members to achieve a degree of party unity in Congress on behalf of his vision of a more decentralized polity. Despite his organizational efforts to create a political party, Jefferson’s party was meant to achieve a degree of national unity, not a lasting-party system. Still influenced by Madison’s fears of factions, Jefferson strove for a degree of national unity and viewed his party organization as a means to such unity. The lack of meaningful party opposition in the 1820’s seemed to achieve Jefferson’s goals. As the Federalist Party receded in strength after the election of 1800, Jefferson’s Republican Party was virtually unchallenged.

This lack of party competition did not prevent the growth of regional differences over issues such as internal improvements, the tariff, the War of 1812, and slavery. The growth of such differences cast a pall over the ideal of American nationhood and set the stage for the divisive elections of 1824 and 1828.

A PARTY SYSTEM AS A FORCE FOR DECENTRALIZATION

Andrew Jackson had become a leading voice for democratizing American politics. His defeat in the 1824 election led to his victory four years later as the head of a formal party organization, the Democratic Party (the new name for Jefferson’s Republicans), the brainchild of New York Senator Martin Van Buren. Van Buren masterfully tied the political popularity of Jackson to the organizational apparatus of the Democratic Party and created the first national party convention in 1832 to tie the presidential nominee to a political coalition. This first experiment in national party politics was nothing more than an assembly of state party leaders. Party conventions would serve to bring together state and local leaders to choose party nominees and create a party platform. Every four years, the “national party” would gather to fulfill these obligations and then disband.

In part because of their federal nature, American parties were neither “small” in Alexis de Tocqueville’s description (meaning that there were no substantial differences) nor ordinarily “great” parties of profound differences. Yet in times of crisis, one or more parties grow in importance to lead the nation through a surrogate constitutional revolution. Such parties realign the nation’s politics through a critical election such as that of 1832, when the Democrats recalled the early Republican spirit of limited government and a decentralized polity. The 1832 election ushered in the first truly competitive party system by witnessing a clash of ideas between Jackson’s Democrats and the opposition Whig Party. Partisan techniques of rallies, party newspapers, and electioneering became staples of American politics.

Though they were now national organizations, political parties existed only as a series of state and local organizations. Reflecting the division of electoral votes by state, the two parties were forces for a decentralized polity. National leaders became dependent on the esteem of local party leaders, who thrived on the federal patronage dispensed by presidents and their supporters.

The very nature of parties that are not “great” in Tocqueville’s analysis prevented the Democrats or Whigs from properly dealing with the issue of slavery . The bipartisan consensus on fundamental issues created an untenable political situation as the ability to compromise on the issue of slavery decreased due to mounting regional pressures that served to overwhelm party loyalty. When Van Buren was defeated for the 1844 Democratic nomination due to the Democratic Party’s two-thirds rule (an internal party rule that required two-thirds of convention delegates to support a candidate for nomination), the chance for the Democratic Party to rally around the antislavery issue passed. The Whigs likewise forfeited the opportunity to attack slavery. Thus was a new party born that would pave the way for a constitutional revolution and challenge the federal system that preserved localism, at least for a moment.

The Republican Party of Abraham Lincoln was created in 1856 and was made up of disaffected Whigs and Democrats and those opposed to the expansion of slavery in general and the passage of the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act in particular. This act allowed for the expansion of slavery into the new territories. The Republican Party was distinct from the old Jeffersonian Republicans in its support of a Hamiltonian plan of economic and social nationalism. Under Lincoln, the Republicans supported and enacted legislation to develop western lands, create agricultural colleges, and provide capital for internal improvements and industrial investment. In opposition, the Democrats recalled the Jeffersonian legacy of a decentralized nation and states’ rights. The success of the Union in the Civil War briefly gave the national government a degree of strength and power it previously lacked. In addition, the political coalition of the Republican Party of the late nineteenth century was made up of business interests and dominant northern religious denominations, all Protestant. The Democrats as the party of the former Confederate states expanded to become the party of all major northeastern cities and the immigrant and Catholic citizens. The identification of these coalition groups remained remarkably durable for nearly 100 years.

The increased activity of the federal government increased the role of local and state party leaders. The local and state party organizations thrived on federal patronage and were provided material support in exchange for votes. Party organizations in urban areas filled their coffers with kickbacks from those companies that successfully received city contracts. This system encouraged party loyalty and discipline but could also frequently erupt in internecine battles. It also served to reorient the federal system away from nationalized, administrative power to a rebirth of a system dominated by state and local interests and party organizations, all of whom had grown more powerful as federal patronage increased.

A MOVEMENT TOWARD NATIONALIZATION

Both major parties at the turn of the twentieth century were essentially conservative, emphasizing to varying degrees Jeffersonian theories of limited government. The Populist and later the Progressive movements broke out of that mold and created a new, modern liberal tradition that would pave the way for the New Deal coalition.

The Republican Party won the critical 1896 election on the basis of its support of sound money and protectionism. But the party faced a severe internal split, with the followers of President William McKinley often clashing with the progressive elements of the party, led by McKinley’s vice president, Theodore Roosevelt . Progressives sought to break the back of the two-party system by favoring strict regulations over party politics and favoring efforts to dismantle urban political machines.

In their efforts to dismantle the traditions of party politics, Progressive reforms included civil service protection to disrupt patronage, primary elections, and nonpartisan local elections. Primary elections in particular became decisive in giving rise to a candidate-centered polity where party organizations and loyalties mattered less in electoral competition. Progressive reforms also paved the way for Franklin Roosevelt’s reconceptualization of party politics in the critical election of 1932.

As the head of the Democratic Party, Franklin Roosevelt created a majority coalition of conservative Southerners, northern liberals, union workers, and African Americans in his 1932 presidential election. Like the critical election of 1860, the Democrats in 1932 led a surrogate constitutional revolution on the meaning of rights with the desire of recasting the rights in the Declaration of Independence to strengthen the ties between democracy and liberty. Roosevelt used his popularity to encourage the Democratic Party to rid itself of the two-thirds rule that had prevented Van Buren’s nomination in 1844. This set in motion a series of events that would draw conservative Southerners out of the Democratic Party and begin to free the party and its presidential nominees from the grips of state and local leaders.

Like Jefferson, Roosevelt conceived of the new Democratic Party as a party to end parties. His creation of the administrative state, with the creation of programs such as Social Security in 1935 that were administered not by patronage hires but by a professional civil service, was designed to replace traditional party politics and the urban machines that sustained it.

Roosevelt’s efforts to destroy party politics were only somewhat successful as the two-party system endured, with Republicans exploiting the post–World War II weakness of the Democrats to win eight presidential elections. Republicans forged a winning strategy behind retired General Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1952 and 1956 but only after accepting key elements of the New Deal, particularly Social Security, and the attendant rise of national administrative power.

Part of the explanation of Republican electoral success in the later half of the twentieth century was the rise of suburbs and the sunbelt states of the South and Southwest, both of which favored Republican candidates. Republican gains came largely through the disarray of the Democratic Party over issues such as civil rights and the war in Vietnam. The 1968 Democratic Convention burst the fissures in the Democratic Party between the antiwar and conservative elements of the party into the open. When the convention failed to support a nominee who had contested party primaries in favor of Lyndon Johnson’s vice president, Hubert Humphrey, the party created a reform commission headed by Senator George McGovern to change its delegate selection rules.

The Democratic Party changed its rules to reflect greater democracy by opening up the process to primary elections, preventing state and local leaders from exerting the same level of influence in the nomination process. This was a key victory for the long hopes of Progressive reformers.

The rise of television as a campaign medium put an emphasis on style and removed the party organization as an intermediary between the citizenry and the candidate. Candidate-centered politics, symbolized by Richard Nixon’s Committee to Reelect the President (CREEP) in 1972, removed the party organization as a force in presidential elections. Subsequent campaign finance reforms and the Supreme Court’s ruling in Buckley v. Valeo (1976) made it impossible to exert controls on television advertising and the amount of money candidates could spend in electoral contests. The Republicans were able to use the rise in crime and welfare dependency against the Democrats in power in the 1960’s. Ronald Reagan forced the Republican party to reexamine its traditional support of Keynesian economics in favor of deficit control coupled with large tax and spending cuts. Reagan’s tax cuts, though responsible for massive budget deficits, proved politically popular for the Republican Party.