Please wait while we process your request

Abortion Argumentative Essay: Definitive Guide

Academic writing

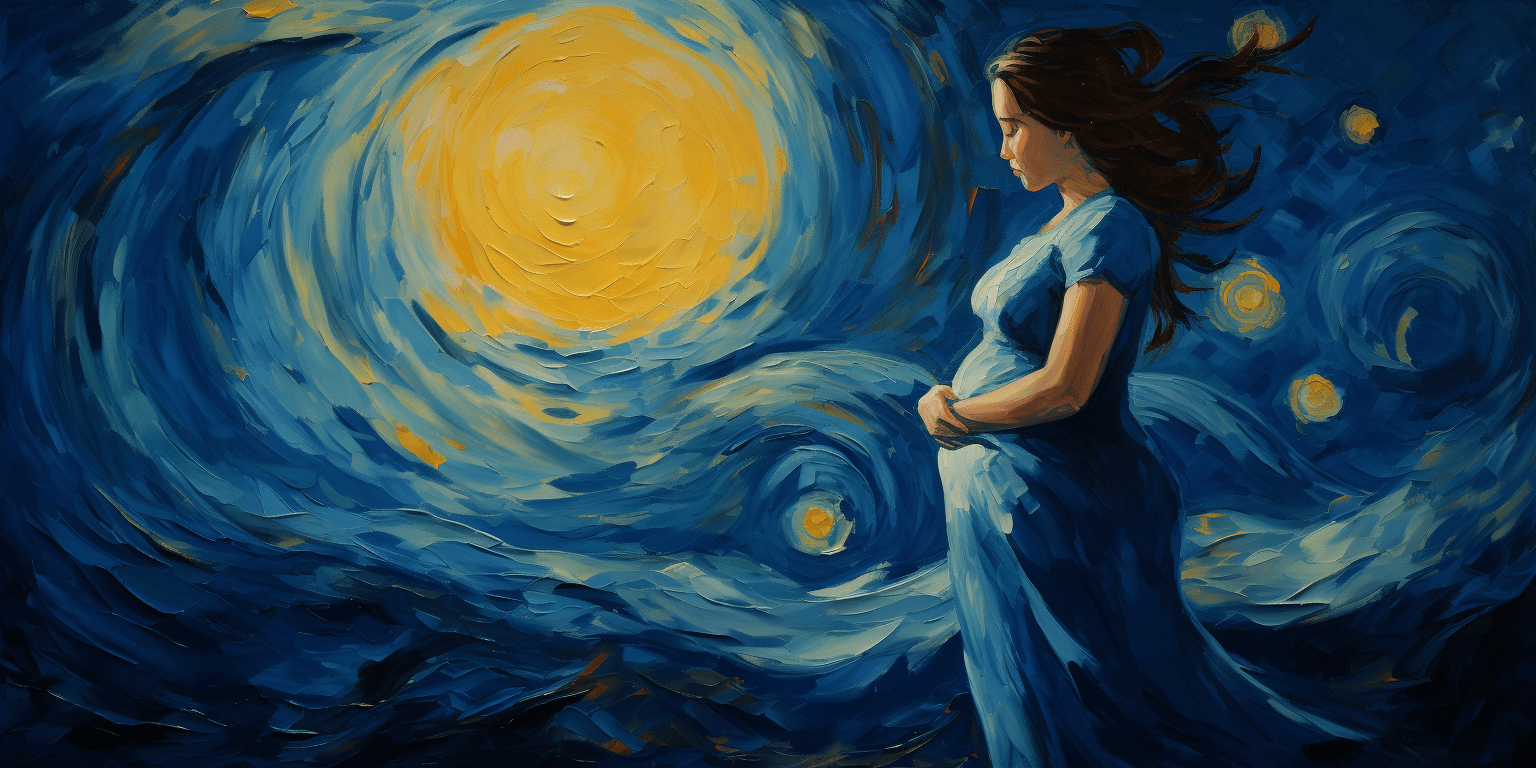

Abortion remains a debatable issue even today, especially in countries like the USA, where a controversial ban was upheld in 13 states at the point this article was written. That’s why an essay on abortion has become one of the most popular tasks in schools, colleges, and universities. When writing this kind of essay, students learn to express their opinion, find and draw arguments and examples, and conduct research.

It’s very easy to speculate on topics like this. However, this makes it harder to find credible and peer-reviewed information on the topic that isn’t merely someone’s opinion. If you were assigned this kind of academic task, do not lose heart. In this article, we will provide you with all the tips and tricks for writing about abortion.

Where to begin?

Conversations about abortion are always emotional. Complex stories, difficult decisions, bitter moments, and terrible diagnoses make this topic hard to cover. Some young people may be shocked by this assignment, while others would be happy to express their opinion on the matter.

One way or another, this topic doesn't leave anyone indifferent. However, it shouldn’t have an effect on the way you approach the research and writing process. What should you remember when working on an argumentative essay about abortion?

- Don’t let your emotions take over. As this is an academic paper, you have to stay impartial and operate with facts. The topic is indeed sore and burning, causing thousands of scandals on the Internet, but you are writing it for school, not a Quora thread.

- Try to balance your opinions. There are always two sides to one story, even if the story is so fragile. You need to present an issue from different angles. This is what your tutors seek to teach you.

- Be tolerant and mind your language. It is very important not to hurt anybody with the choice of words in your essay. So make sure you avoid any possible rough words. It is important to respect people with polar opinions, especially when it comes to academic writing.

- Use facts, not claims. Your essay cannot be based solely on your personal ideas – your conclusions should be derived from facts. Roe v. Wade case, WHO or Mayo Clinic information, and CDC are some of the sources you can rely on.

Speaking of Outline

An argumentative essay on abortion outline is a must-have even for experienced writers. In general, each essay, irrespective of its kind or topic, has a strict outline. It may be brief or extended, but the major parts are always the same:

- Introduction. This is a relatively short paragraph that starts with a hook and presents the background information on the topic. It should end with a thesis statement telling your reader what your main goal or idea is.

- Body. This section usually consists of 2-4 paragraphs. Each one has its own structure: main argument + facts to support it + small conclusion and transition into the next paragraph.

- Conclusion. In this part, your task is to summarize all your thoughts and come to a general conclusive idea. You may have to restate some info from the body and your thesis statement and add a couple of conclusive statements without introducing new facts.

Why is it important to create an outline?

- You will structure your ideas. We bet you’ve got lots on your mind. Writing them down and seeing how one can flow logically into the other will help you create a consistent paper. Naturally, you will have to abandon some of the ideas if they don’t fit the overall narrative you’re building.

- You can get some inspiration. While creating your outline, which usually consists of some brief ideas, you can come up with many more to research. Some will add to your current ones or replace them with better options.

- You will find the most suitable sources. Argumentative essay writing requires you to use solid facts and trustworthy arguments built on them. When the topic is as controversial as abortion, these arguments should be taken from up-to-date, reliable sources. With an outline, you will see if you have enough to back up your ideas.

- You will write your text as professionals do. Most expert writers start with outlines to write the text faster and make it generally better. As you will have your ideas structured, the general flow of thoughts will be clear. And, of course, it will influence your overall grade positively.

Abortion Essay Introduction

The introduction is perhaps the most important part of the whole essay. In this relatively small part, you will have to present the issue under consideration and state your opinion on it. Here is a typical introduction outline:

- The first sentence is a hook grabbing readers' attention.

- A few sentences that go after elaborate on the hook. They give your readers some background and explain your research.

- The last sentence is a thesis statement showing the key idea you are building your text around.

Before writing an abortion essay intro, first thing first, you will need to define your position. If you are in favor of this procedure, what exactly made you think so? If you are an opponent of abortion, determine how to argue your position. In both cases, you may research the point of view in medicine, history, ethics, and other fields.

When writing an introduction, remember:

- Never repeat your title. First of all, it looks too obvious; secondly, it may be boring for your reader right from the start. Your first sentence should be a well-crafted hook. The topic of abortion worries many people, so it’s your chance to catch your audience’s attention with some facts or shocking figures.

- Do not make it too long. Your task here is to engage your audience and let them know what they are about to learn. The rest of the information will be disclosed in the main part. Nobody likes long introductions, so keep it short but informative.

- Pay due attention to the thesis statement. This is the central sentence of your introduction. A thesis statement in your abortion intro paragraph should show that you have a well-supported position and are ready to argue it. Therefore, it has to be strong and convey your idea as clearly as possible. We advise you to make several options for the thesis statement and choose the strongest one.

Hooks for an Abortion Essay

Writing a hook is a good way to catch the attention of your audience, as this is usually the first sentence in an essay. How to start an essay about abortion? You can begin with some shocking fact, question, statistics, or even a quote. However, always make sure that this piece is taken from a trusted resource.

Here are some examples of hooks you can use in your paper:

- As of July 1, 2022, 13 states banned abortion, depriving millions of women of control of their bodies.

- According to WHO, 125,000 abortions take place every day worldwide.

- Is abortion a woman’s right or a crime?

- Since 1994, more than 40 countries have liberalized their abortion laws.

- Around 48% of all abortions are unsafe, and 8% of them lead to women’s death.

- The right to an abortion is one of the reproductive and basic rights of a woman.

- Abortion is as old as the world itself – women have resorted to this method since ancient times.

- Only 60% of women in the world live in countries where pregnancy termination is allowed.

Body Paragraphs: Pros and Cons of Abortion

The body is the biggest part of your paper. Here, you have a chance to make your voice concerning the abortion issue heard. Not sure where to start? Facts about abortion pros and cons should give you a basic understanding of which direction to move in.

First things first, let’s review some brief tips for you on how to write the best essay body if you have already made up your mind.

Make a draft

It’s always a good idea to have a rough draft of your writing. Follow the outline and don’t bother with the word choice, grammar, or sentence structure much at first. You can polish it all later, as the initial draft will not likely be your final. You may see some omissions in your arguments, lack of factual basis, or repetitiveness that can be eliminated in the next versions.

Trust only reliable sources

This part of an essay includes loads of factual information, and you should be very careful with it. Otherwise, your paper may look unprofessional and cost you precious points. Never rely on sources like Wikipedia or tabloids – they lack veracity and preciseness.

Edit rigorously

It’s best to do it the next day after you finish writing so that you can spot even the smallest mistakes. Remember, this is the most important part of your paper, so it has to be flawless. You can also use editing tools like Grammarly.

Determine your weak points

Since you are writing an argumentative essay, your ideas should be backed up by strong facts so that you sound convincing. Sometimes it happens that one argument looks weaker than the other. Your task is to find it and strengthen it with more or better facts.

Add an opposing view

Sometimes, it’s not enough to present only one side of the discussion. Showing one of the common views from the opposing side might actually help you strengthen your main idea. Besides, making an attempt at refuting it with alternative facts can show your teacher or professor that you’ve researched and analyzed all viewpoints, not just the one you stand by.

If you have chosen a side but are struggling to find the arguments for or against it, we have complied abortion pro and cons list for you. You can use both sets if you are writing an abortion summary essay covering all the stances.

Why Should Abortion Be Legal

If you stick to the opinion that abortion is just a medical procedure, which should be a basic health care need for each woman, you will definitely want to write the pros of abortion essay. Here is some important information and a list of pros about abortion for you to use:

- Since the fetus is a set of cells – not an individual, it’s up to a pregnant woman to make a decision concerning her body. Only she can decide whether she wants to keep the pregnancy or have an abortion. The abortion ban is a violation of a woman’s right to have control over her own body.

- The fact that women and girls do not have access to effective contraception and safe abortion services has serious consequences for their own health and the health of their families.

- The criminalization of abortion usually leads to an increase in the number of clandestine abortions. Many years ago, fetuses were disposed of with improvised means, which included knitting needles and half-straightened metal hangers. 13% of women’s deaths are the result of unsafe abortions.

- Many women live in a difficult financial situation and cannot support their children financially. Having access to safe abortion takes this burden off their shoulders. This will also not decrease their quality of life as the birth and childcare would.

- In countries where abortion is prohibited, there is a phenomenon of abortion tourism to other countries where it can be done without obstacles. Giving access to this procedure can make the lives of women much easier.

- Women should not put their lives or health in danger because of the laws that were adopted by other people.

- Girls and women who do not have proper sex education may not understand pregnancy as a concept or determine that they are pregnant early on. Instead of educating them and giving them a choice, an abortion ban forces them to become mothers and expects them to be fit parents despite not knowing much about reproduction.

- There are women who have genetic disorders or severe mental health issues that will affect their children if they're born. Giving them an option to terminate ensures that there won't be a child with a low quality of life and that the woman will not have to suffer through pregnancy, birth, and raising a child with her condition.

- Being pro-choice is about the freedom to make decisions about your body so that women who are for termination can do it safely, and those who are against it can choose not to do it. It is an inclusive option that caters to everyone.

- Women and girls who were raped or abused by their partner, caregiver, or stranger and chose to terminate the pregnancy can now be imprisoned for longer than their abusers. This implies that the system values the life of a fetus with no or primitive brain function over the life of a living woman.

- People who lived in times when artificial termination of pregnancy was scarcely available remember clandestine abortions and how traumatic they were, not only for the physical but also for the mental health of women. Indeed, traditionally, in many countries, large families were a norm. However, the times have changed, and supervised abortion is a safe and accessible procedure these days. A ban on abortion will simply push humanity away from the achievements of the civilized world.

Types of abortion

There are 2 main types of abortions that can be performed at different pregnancy stages and for different reasons:

- Medical abortion. It is performed by taking a specially prescribed pill. It does not require any special manipulations and can even be done at home (however, after a doctor’s visit and under supervision). It is considered very safe and is usually done during the very first weeks of pregnancy.

- Surgical abortion. This is a medical operation that is done with the help of a suction tube. It then removes the fetus and any related material. Anesthesia is used for this procedure, and therefore, it can only be done in a hospital. The maximum time allowed for surgical abortion is determined in each country specifically.

Cases when abortion is needed

Center for Reproductive Rights singles out the following situations when abortion is required:

- When there is a risk to the life or physical/mental health of a pregnant woman.

- When a pregnant woman has social or economic reasons for it.

- Upon the woman's request.

- If a pregnant woman is mentally or cognitively disabled.

- In case of rape and/or incest.

- If there were congenital anomalies detected in the fetus.

Countries and their abortion laws

- Countries where abortion is legalized in any case: Australia, Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Sweden, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Hungary, the Netherlands, Norway, Ukraine, Moldova, Latvia, Lithuania, etc.

- Countries where abortion is completely prohibited: Angola, Venezuela, Egypt, Indonesia, Iraq, Lebanon, Nicaragua, Oman, Paraguay, Palau, Jamaica, Laos, Haiti, Honduras, Andorra, Aruba, El Salvador, Dominican Republic, Sierra Leone, Senegal, etc.

- Countries where abortion is allowed for medical reasons: Afghanistan, Israel, Argentina, Nigeria, Bangladesh, Bolivia, Ghana, Israel, Morocco, Mexico, Bahamas, Central African Republic, Ecuador, Ghana, Algeria, Monaco, Pakistan, Poland, etc.

- Countries where abortion is allowed for both medical and socioeconomic reasons: England, India, Spain, Luxembourg, Japan, Finland, Taiwan, Zambia, Iceland, Fiji, Cyprus, Barbados, Belize, etc.

Why Abortion Should Be Banned

Essays against abortions are popular in educational institutions since we all know that many people – many minds. So if you don’t want to support this procedure in your essay, here are some facts that may help you to argument why abortion is wrong:

- Abortion at an early age is especially dangerous because a young woman with an unstable hormonal system may no longer be able to have children throughout her life. Termination of pregnancy disrupts the hormonal development of the body.

- Health complications caused by abortion can occur many years after the procedure. Even if a woman feels fine in the short run, the situation may change in the future.

- Abortion clearly has a negative effect on reproductive function. Artificial dilation of the cervix during an abortion leads to weak uterus tonus, which can cause a miscarriage during the next pregnancy.

- Evidence shows that surgical termination of pregnancy significantly increases the risk of breast cancer.

- In December 1996, the session of the Council of Europe on bioethics concluded that a fetus is considered a human being on the 14th day after conception.

You are free to use each of these arguments for essays against abortions. Remember that each claim should not be supported by emotions but by facts, figures, and so on.

Health complications after abortion

One way or another, abortion is extremely stressful for a woman’s body. Apart from that, it can even lead to various health problems in the future. You can also cover them in your cons of an abortion essay:

- Continuation of pregnancy. If the dose of the drug is calculated by the doctor in the wrong way, the pregnancy will progress.

- Uterine bleeding, which requires immediate surgical intervention.

- Severe nausea or even vomiting occurs as a result of a sharp change in the hormonal background.

- Severe stomach pain. Medical abortion causes miscarriage and, as a result, strong contractions of the uterus.

- High blood pressure and allergic reactions to medicines.

- Depression or other mental problems after a difficult procedure.

Abortion Essay Conclusion

After you have finished working on the previous sections of your paper, you will have to end it with a strong conclusion. The last impression is no less important than the first one. Here is how you can make it perfect in your conclusion paragraph on abortion:

- It should be concise. The conclusion cannot be as long as your essay body and should not add anything that cannot be derived from the main section. Reiterate the key ideas, combine some of them, and end the paragraph with something for the readers to think about.

- It cannot repeat already stated information. Restate your thesis statement in completely other words and summarize your main points. Do not repeat anything word for word – rephrase and shorten the information instead.

- It should include a call to action or a cliffhanger. Writing experts believe that a rhetorical question works really great for an argumentative essay. Another good strategy is to leave your readers with some curious ideas to ponder upon.

Abortion Facts for Essay

Abortion is a topic that concerns most modern women. Thousands of books, research papers, and articles on abortion are written across the world. Even though pregnancy termination has become much safer and less stigmatized with time, it still worries millions. What can you cover in your paper so that it can really stand out among others? You may want to add some shocking abortion statistics and facts:

- 40-50 million abortions are done in the world every year (approximately 125,000 per day).

- According to UN statistics, women have 25 million unsafe abortions each year. Most of them (97%) are performed in the countries of Africa, Asia, and Latin America. 14% of them are especially unsafe because they are done by people without any medical knowledge.

- Since 2017, the United States has shown the highest abortion rate in the last 30 years.

- The biggest number of abortion procedures happen in the countries where they are officially banned. The lowest rate is demonstrated in the countries with high income and free access to contraception.

- Women in low-income regions are three times more susceptible to unplanned pregnancies than those in developed countries.

- In Argentina, more than 38,000 women face dreadful health consequences after unsafe abortions.

- The highest teen abortion rates in the world are seen in 3 countries: England, Wales, and Sweden.

- Only 31% of teenagers decide to terminate their pregnancy. However, the rate of early pregnancies is getting lower each year.

- Approximately 13 million children are born to mothers under the age of 20 each year.

- 5% of women of reproductive age live in countries where abortions are prohibited.

We hope that this abortion information was useful for you, and you can use some of these facts for your own argumentative essay. If you find some additional facts, make sure that they are not manipulative and are taken from official medical resources.

Abortion Essay Topics

Do you feel like you are lost in the abundance of information? Don’t know what topic to choose among the thousands available online? Check our short list of the best abortion argumentative essay topics:

- Why should abortion be legalized essay

- Abortion: a murder or a basic human right?

- Why we should all support abortion rights

- Is the abortion ban in the US a good initiative?

- The moral aspect of teen abortions

- Can the abortion ban solve birth control problems?

- Should all countries allow abortion?

- What consequences can abortion have in the long run?

- Is denying abortion sexist?

- Why is abortion a human right?

- Are there any ethical implications of abortion?

- Do you consider abortion a crime?

- Should women face charges for terminating a pregnancy?

Want to come up with your own? Here is how to create good titles for abortion essays:

- Write down the first associations. It can be something that swirls around in your head and comes to the surface when you think about the topic. These won’t necessarily be well-written headlines, but each word or phrase can be the first link in the chain of ideas that leads you to the best option.

- Irony and puns are not always a good idea. Especially when it comes to such difficult topics as abortion. Therefore, in your efforts to be original, remain sensitive to the issue you want to discuss.

- Never make a quote as your headline. First, a wordy quote makes the headline long. Secondly, readers do not understand whose words are given in the headline. Therefore, it may confuse them right from the start. If you have found a great quote, you can use it as your hook, but don’t forget to mention its author.

- Try to briefly summarize what is said in the essay. What is the focus of your paper? If the essence of your argumentative essay can be reduced to one sentence, it can be used as a title, paraphrased, or shortened.

- Write your title after you have finished your text. Before you just start writing, you might not yet have a catchy phrase in mind to use as a title. Don’t let it keep you from working on your essay – it might come along as you write.

Abortion Essay Example

We know that it is always easier to learn from a good example. For this reason, our writing experts have complied a detailed abortion essay outline for you. For your convenience, we have created two options with different opinions.

Topic: Why should abortion be legal?

Introduction – hook + thesis statement + short background information

Essay hook: More than 59% of women in the world do not have access to safe abortions, which leads to dreading health consequences or even death.

Thesis statement: Since banning abortions does not decrease their rates but only makes them unsafe, it is not logical to ban abortions.

Body – each paragraph should be devoted to one argument

Argument 1: Woman’s body – women’s rules. + example: basic human rights.

Argument 2: Banning abortion will only lead to more women’s death. + example: cases of Polish women.

Argument 3: Only women should decide on abortion. + example: many abortion laws are made by male politicians who lack knowledge and first-hand experience in pregnancies.

Conclusion – restated thesis statement + generalized conclusive statements + cliffhanger

Restated thesis: The abortion ban makes pregnancy terminations unsafe without decreasing the number of abortions, making it dangerous for women.

Cliffhanger: After all, who are we to decide a woman’s fate?

Topic: Why should abortion be banned?

Essay hook: Each year, over 40 million new babies are never born because their mothers decide to have an abortion.

Thesis statement: Abortions on request should be banned because we cannot decide for the baby whether it should live or die.

Argument 1: A fetus is considered a person almost as soon as it is conceived. Killing it should be regarded as murder. + example: Abortion bans in countries such as Poland, Egypt, etc.

Argument 2: Interrupting a baby’s life is morally wrong. + example: The Bible, the session of the Council of Europe on bioethics decision in 1996, etc.

Argument 3: Abortion may put the reproductive health of a woman at risk. + example: negative consequences of abortion.

Restated thesis: Women should not be allowed to have abortions without serious reason because a baby’s life is as priceless as their own.

Cliffhanger: Why is killing an adult considered a crime while killing an unborn baby is not?

Examples of Essays on Abortion

There are many great abortion essays examples on the Web. You can easily find an argumentative essay on abortion in pdf and save it as an example. Many students and scholars upload their pieces to specialized websites so that others can read them and continue the discussion in their own texts.

In a free argumentative essay on abortion, you can look at the structure of the paper, choice of the arguments, depth of research, and so on. Reading scientific papers on abortion or essays of famous activists is also a good idea. Here are the works of famous authors discussing abortion.

A Defense of Abortion by Judith Jarvis Thomson

Published in 1971, this essay by an American philosopher considers the moral permissibility of abortion. It is considered the most debated and famous essay on this topic, and it’s definitely worth reading no matter what your stance is.

Abortion and Infanticide by Michael Tooley

It was written in 1972 by an American philosopher known for his work in the field of metaphysics. In this essay, the author considers whether fetuses and infants have the same rights. Even though this work is quite complex, it presents some really interesting ideas on the matter.

Some Biological Insights into Abortion by Garret Hardin

This article by American ecologist Garret Hardin, who had focused on the issue of overpopulation during his scholarly activities, presents some insights into abortion from a scientific point of view. He also touches on non-biological issues, such as moral and economic. This essay will be of great interest to those who support the pro-choice stance.

H4 Hidden in Plain View: An Overview of Abortion in Rural Illinois and Around the Globe by Heather McIlvaine-Newsad

In this study, McIlvaine-Newsad has researched the phenomenon of abortion since prehistoric times. She also finds an obvious link between the rate of abortions and the specifics of each individual country. Overall, this scientific work published in 2014 is extremely interesting and useful for those who want to base their essay on factual information.

H4 Reproduction, Politics, and John Irving’s The Cider House Rules: Women’s Rights or “Fetal Rights”? by Helena Wahlström

In her article of 2013, Wahlström considers John Irving’s novel The Cider House Rules published in 1985 and is regarded as a revolutionary work for that time, as it acknowledges abortion mostly as a political problem. This article will be a great option for those who want to investigate the roots of the abortion debate.

FAQs On Abortion Argumentative Essay

- Is abortion immoral?

This question is impossible to answer correctly because each person independently determines their own moral framework. One group of people will say that abortion is a woman’s right because only she has power over her body and can make decisions about it. Another group will argue that the embryo is also a person and has the right to birth and life.

In general, the attitude towards abortion is determined based on the political and religious views of each person. Religious people generally believe that abortion is immoral because it is murder, while secular people see it as a normal medical procedure. For example, in the US, the ban on abortion was introduced in red states where the vast majority have conservative views, while blue liberal states do not support this law. Overall, it’s up to a person to decide whether they consider abortion immoral based on their own values and beliefs.

- Is abortion legal?

The answer to this question depends on the country in which you live. There are countries in which pregnancy termination is a common medical procedure and is performed at the woman's request. There are also states in which there must be a serious reason for abortion: medical, social, or economic. Finally, there are nations in which abortion is prohibited and criminalized. For example, in Jamaica, a woman can get life imprisonment for abortion, while in Kenya, a medical worker who volunteers to perform an abortion can be imprisoned for up to 14 years.

- Is abortion safe?

In general, modern medicine has reached such a level that abortion has become a common (albeit difficult from various points of view) medical procedure. There are several types of abortion, as well as many medical devices and means that ensure the maximum safety of the pregnancy termination. Like all other medical procedures, abortion can have various consequences and complications.

Abortions – whether safe or not - exist in all countries of the world. The thing is that more than half of them are dangerous because women have them in unsuitable conditions and without professional help. Only universal access to abortion in all parts of the world can make it absolutely safe. In such a case, it will be performed only after a thorough assessment and under the control of a medical professional who can mitigate the potential risks.

- How safe is abortion?

If we do not talk about the ethical side of the issue related to abortion, it still has some risks. In fact, any medical procedure has them to a greater or lesser extent.

The effectiveness of the safe method in a medical setting is 80-99%. An illegal abortion (for example, the one without special indications after 12 weeks) can lead to a patient’s death, and the person who performed it will be criminally liable in this case.

Doctors do not have universal advice for all pregnant women on whether it is worth making this decision or not. However, many of them still tend to believe that any contraception - even one that may have negative side effects - is better than abortion. That’s why spreading awareness on means of contraception and free access to it is vital.

Your email address will not be published / Required fields are marked *

Try it now!

Calculate your price

Number of pages:

Order an essay!

Fill out the order form

Make a secure payment

Receive your order by email

Essay paper writing

Writing About Nuclear Power

The topic of nuclear energy is still considered one of the hottest in modern society. Many people argue whether nuclear energy has to be used and what are its alternatives. That is why nuclear energy…

24th Jul 2020

Writing about Freedom of Speech and Censorship

Freedom of speech is an important and inalienable right, which determines the degree of liberation and democracy of the society. Voltaire wrote that people have no freedom without the right to…

17th Jul 2020

How To Structure A Term Paper?

Structure and format are crucial for tutors when it comes to assessing the paper. Your assignment might be great within the content, however, if it does not meet the basic requirements in terms of…

14th Aug 2017

Get your project done perfectly

Professional writing service

Reset password

We’ve sent you an email containing a link that will allow you to reset your password for the next 24 hours.

Please check your spam folder if the email doesn’t appear within a few minutes.

Persuasive Essay Guide

Persuasive Essay About Abortion

Crafting a Convincing Persuasive Essay About Abortion

-9248.jpg&w=640&q=75)

People also read

A Comprehensive Guide to Writing an Effective Persuasive Essay

200+ Persuasive Essay Topics to Help You Out

Learn How to Create a Persuasive Essay Outline

30+ Free Persuasive Essay Examples To Get You Started

Read Excellent Examples of Persuasive Essay About Gun Control

How to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid19 | Examples & Tips

Learn to Write Persuasive Essay About Business With Examples and Tips

Check Out 12 Persuasive Essay About Online Education Examples

Persuasive Essay About Smoking - Making a Powerful Argument with Examples

Are you about to write a persuasive essay on abortion but wondering how to begin?

Writing an effective persuasive essay on the topic of abortion can be a difficult task for many students.

It is important to understand both sides of the issue and form an argument based on facts and logical reasoning. This requires research and understanding, which takes time and effort.

In this blog, we will provide you with some easy steps to craft a persuasive essay about abortion that is compelling and convincing. Moreover, we have included some example essays and interesting facts to read and get inspired by.

So let's start!

- 1. How To Write a Persuasive Essay About Abortion?

- 2. Persuasive Essay About Abortion Examples

- 3. Examples of Argumentative Essay About Abortion

- 4. Abortion Persuasive Essay Topics

- 5. Facts About Abortion You Need to Know

How To Write a Persuasive Essay About Abortion?

Abortion is a controversial topic, with people having differing points of view and opinions on the matter. There are those who oppose abortion, while some people endorse pro-choice arguments.

It is also an emotionally charged subject, so you need to be extra careful when crafting your persuasive essay .

Before you start writing your persuasive essay, you need to understand the following steps.

Step 1: Choose Your Position

The first step to writing a persuasive essay on abortion is to decide your position. Do you support the practice or are you against it? You need to make sure that you have a clear opinion before you begin writing.

Once you have decided, research and find evidence that supports your position. This will help strengthen your argument.

Check out the video below to get more insights into this topic:

Step 2: Choose Your Audience

The next step is to decide who your audience will be. Will you write for pro-life or pro-choice individuals? Or both?

Knowing who you are writing for will guide your writing and help you include the most relevant facts and information.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That's our Job!

Step 3: Define Your Argument

Now that you have chosen your position and audience, it is time to craft your argument.

Start by defining what you believe and why, making sure to use evidence to support your claims. You also need to consider the opposing arguments and come up with counter arguments. This helps make your essay more balanced and convincing.

Step 4: Format Your Essay

Once you have the argument ready, it is time to craft your persuasive essay. Follow a standard format for the essay, with an introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion.

Make sure that each paragraph is organized and flows smoothly. Use clear and concise language, getting straight to the point.

Step 5: Proofread and Edit

The last step in writing your persuasive essay is to make sure that you proofread and edit it carefully. Look for spelling, grammar, punctuation, or factual errors and correct them. This will help make your essay more professional and convincing.

These are the steps you need to follow when writing a persuasive essay on abortion. It is a good idea to read some examples before you start so you can know how they should be written.

Continue reading to find helpful examples.

Persuasive Essay About Abortion Examples

To help you get started, here are some example persuasive essays on abortion that may be useful for your own paper.

Short Persuasive Essay About Abortion

Persuasive Essay About No To Abortion

What Is Abortion? - Essay Example

Persuasive Speech on Abortion

Legal Abortion Persuasive Essay

Persuasive Essay About Abortion in the Philippines

Persuasive Essay about legalizing abortion

You can also read m ore persuasive essay examples to imp rove your persuasive skills.

Examples of Argumentative Essay About Abortion

An argumentative essay is a type of essay that presents both sides of an argument. These essays rely heavily on logic and evidence.

Here are some examples of argumentative essay with introduction, body and conclusion that you can use as a reference in writing your own argumentative essay.

Abortion Persuasive Essay Introduction

Argumentative Essay About Abortion Conclusion

Argumentative Essay About Abortion Pdf

Argumentative Essay About Abortion in the Philippines

Argumentative Essay About Abortion - Introduction

Abortion Persuasive Essay Topics

If you are looking for some topics to write your persuasive essay on abortion, here are some examples:

- Should abortion be legal in the United States?

- Is it ethical to perform abortions, considering its pros and cons?

- What should be done to reduce the number of unwanted pregnancies that lead to abortions?

- Is there a connection between abortion and psychological trauma?

- What are the ethical implications of abortion on demand?

- How has the debate over abortion changed over time?

- Should there be legal restrictions on late-term abortions?

- Does gender play a role in how people view abortion rights?

- Is it possible to reduce poverty and unwanted pregnancies through better sex education?

- How is the anti-abortion point of view affected by religious beliefs and values?

These are just some of the potential topics that you can use for your persuasive essay on abortion. Think carefully about the topic you want to write about and make sure it is something that interests you.

Check out m ore persuasive essay topics that will help you explore other things that you can write about!

Tough Essay Due? Hire Tough Writers!

Facts About Abortion You Need to Know

Here are some facts about abortion that will help you formulate better arguments.

- According to the Guttmacher Institute , 1 in 4 pregnancies end in abortion.

- The majority of abortions are performed in the first trimester.

- Abortion is one of the safest medical procedures, with less than a 0.5% risk of major complications.

- In the United States, 14 states have laws that restrict or ban most forms of abortion after 20 weeks gestation.

- Seven out of 198 nations allow elective abortions after 20 weeks of pregnancy.

- In places where abortion is illegal, more women die during childbirth and due to complications resulting from pregnancy.

- A majority of pregnant women who opt for abortions do so for financial and social reasons.

- According to estimates, 56 million abortions occur annually.

In conclusion, these are some of the examples, steps, and topics that you can use to write a persuasive essay. Make sure to do your research thoroughly and back up your arguments with evidence. This will make your essay more professional and convincing.

Need the services of a professional essay writing service ? We've got your back!

MyPerfectWords.com is a persuasive essay writing service that provides help to students in the form of professionally written essays. Our persuasive essay writer can craft quality persuasive essays on any topic, including abortion.

Frequently Asked Questions

What should i talk about in an essay about abortion.

When writing an essay about abortion, it is important to cover all the aspects of the subject. This includes discussing both sides of the argument, providing facts and evidence to support your claims, and exploring potential solutions.

What is a good argument for abortion?

A good argument for abortion could be that it is a woman’s choice to choose whether or not to have an abortion. It is also important to consider the potential risks of carrying a pregnancy to term.

Write Essay Within 60 Seconds!

Caleb S. has been providing writing services for over five years and has a Masters degree from Oxford University. He is an expert in his craft and takes great pride in helping students achieve their academic goals. Caleb is a dedicated professional who always puts his clients first.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

Home — Blog — Topic Ideas — 50 Abortion Essay Topics: Researching Abortion-Related Subjects

50 Abortion Essay Topics: Researching Abortion-Related Subjects

Abortion remains a contentious social and political issue, with deeply held beliefs and strong emotions shaping the debate. It is a topic that has been at the forefront of public discourse for decades, sparking heated arguments and evoking a range of perspectives from individuals, organizations, and governments worldwide.

The complexity of abortion stems from its intersection with fundamental human rights, ethical principles, and societal norms. It raises questions about the sanctity of life, individual autonomy, gender equality, and public health, making it a challenging yet critically important subject to explore and analyze.

This guide provides a comprehensive overview of the significance of choosing the right abortion essay topics and abortion title ideas , offering valuable insights and practical advice for students navigating this challenging yet rewarding endeavor. By understanding the multifaceted nature of abortion and its far-reaching implications, students can make informed decisions about their topic selection, setting themselves up for success in producing well-researched, insightful, and impactful essays.

Choosing the Right Abortion Essay Topic

For students who are tasked with writing an essay on abortion, choosing the right topic is essential. A well-chosen topic can be the difference between a well-researched, insightful, and impactful piece of writing and a superficial, uninspired, and forgettable one.

This guide delves into the significance of selecting the right abortion essay topic, providing valuable insights for students embarking on this challenging yet rewarding endeavor. By understanding the multifaceted nature of abortion and its far-reaching implications, students can identify topics that align with their interests, research capabilities, and the overall objectives of their essays.

Abortion remains a contentious social and political issue, with deeply held beliefs and strong emotions shaping the debate on abortion topics . It is a topic that has been at the forefront of public discourse for decades, sparking heated arguments and evoking a range of perspectives from individuals, organizations, and governments worldwide.

List of Abortion Argumentative Essay Topics

Abortion argumentative essay topics typically revolve around the ethical, legal, and societal aspects of this controversial issue. These topics often involve debates and discussions, requiring students to present well-reasoned arguments supported by evidence and persuasive language.

- The Bodily Autonomy vs. Fetal Rights Debate: A Balancing Act

- Navigating the Ethical Labyrinth of Abortion: Life, Choice, and Consequences

- Championing Gender Equality and Reproductive Freedom in the Abortion Debate

- Considering Abortion as a Human Right

- The Impact of Abortion Stigma on Women's Mental Health and Well-being

- The Impact of Abortion Restrictions on Poverty, Inequality, and Social Disparities

- Addressing Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Abortion Access and Health Outcomes

- Analyzing the Impact of Public Opinion and Voter Attitudes on Abortion Legislation

- Discussion on Whether Abortion is a Crime

- Abortion Restrictions and Women's Economic Opportunity

- Government Intervention in Abortion Regulation

- Religion, Morality, and Abortion Attitudes

- Parental Notification and Consent Laws

- Education and Counseling for Informed Abortion Choices

- Media Representation and Abortion Perceptions

Ethical Considerations: Abortion raises profound ethical questions about the sanctity of life, personhood, and individual choice. Students can explore these ethical dilemmas by examining the moral implications of abortion, the rights of the unborn, and the role of personal conscience in decision-making.

Legal Aspects: The legal landscape surrounding abortion is constantly evolving, with varying regulations and restrictions across different jurisdictions. Students can delve into the legal aspects of abortion by analyzing the impact of laws and policies on access, safety, and the well-being of women.

Societal Impact: Abortion has a significant impact on society, influencing public health, gender equality, and social justice. Students can explore the societal implications of abortion by examining its impact on maternal health, reproductive rights, and the lives of marginalized communities.

Effective Abortion Topics for Research Paper

Research papers on abortion demand a more in-depth and comprehensive approach, requiring students to delve into historical, medical, and international perspectives on this multifaceted issue.

Medical Perspectives: The medical aspects of abortion encompass a wide range of topics, from advancements in abortion procedures to the health and safety of women undergoing the procedure. Students can explore medical perspectives by examining the evolution of abortion techniques, the impact of medical interventions on maternal health, and the role of healthcare providers in the abortion debate.

Historical Analysis: Abortion has a long and complex history, with changing attitudes, practices, and laws across different eras. Students can engage in historical analysis by examining the evolution of abortion practices in ancient civilizations, tracing the legal developments surrounding abortion, and exploring the shifting social attitudes towards abortion throughout history.

International Comparisons: Abortion laws and regulations vary widely across different countries, leading to diverse experiences and outcomes. Students can make international comparisons by examining abortion access and restrictions in different regions, analyzing the impact of varying legal frameworks on women's health and rights, and identifying best practices in abortion policies.

List of Abortion Research Paper Topics

- The Socioeconomic Factors and Racial Disparities Shaping Abortion Access

- Ethical and Social Implications of Emerging Abortion Technologies

- Abortion Stigma and Women's Mental Health

- Telemedicine and Abortion Access in Rural Areas

- International Human Rights and Abortion Access

- Reproductive Justice and Other Social Justice Issues

- Men's Role in Abortion Decision-Making

- Abortion Restrictions and Social Disparities

- Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Abortion Access

- Alternative Approaches to Abortion Regulation

- Political Ideology and Abortion Policy Debates

- Public Health Campaigns for Informed Abortion Decisions

- Abortion Services in Conflict-Affected Areas

- Healthcare Providers and Medical Ethics of Abortion

- International Cooperation on Abortion Policies

By exploring these topics and subtopics for abortion essays , students can gain a more comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted nature of the abortion debate and choose a specific focus that aligns with their interests and research objectives.

Choosing Abortion Research Paper Topics

When selecting research paper topics on abortion, it is essential to consider factors such as research feasibility, availability of credible sources, and the potential for original contributions.

Abortion is a complex and multifaceted issue that intersects with various aspects of society and individual lives. By broadening the scope of abortion-related topics, students can explore a wider range of perspectives and insights.

- Demystifying Abortion Statistics: Understanding the Global and Domestic Landscape

- Abortion and Women's Rights: A Historical and Contemporary Perspective

- Decoding the Impact of Abortion on Public Health and Social Welfare

- Unveiling the Role of Media and Public Discourse in Shaping Abortion Perceptions

- Comparative Analysis of Abortion Laws Worldwide

- Historical Evolution of Abortion Rights and Practices

- Impact of Abortion on Public Health and Maternal Mortality

- Abortion Funding and Access to Reproductive Healthcare

- Role of Misinformation and Myths in Abortion Debates

- International Perspectives on Abortion and Reproductive Freedom

- Abortion and the UN Sustainable Development Goals

- Abortion and Gender Equality in the Global Context

- Abortion and Human Rights: A Legal and Ethical Analysis

- Religious and Cultural Influences on Abortion Perceptions

- Abortion and Social Justice: Addressing Disparities and Marginalization

- Anti-abortion and Pro-choice Movements: Comparative Analysis and Impact

- Impact of Technological Advancements on Abortion Procedures and Access

- Ethical Considerations of New Abortion Technologies and Surrogacy

- Role of Advocacy and Activism in Shaping Abortion Policy and Practice

- Measuring the Effectiveness of Abortion Policy Interventions

Navigating the complex landscape of abortion-related topics can be a daunting task, but it also offers an opportunity for students to delve into a range of compelling issues and perspectives. By choosing the right topic, students can produce well-researched, insightful, and impactful essays that contribute to the ongoing dialogue on this important subject.

The 50 abortion essay ideas presented in this guide provide a starting point for exploring the intricacies of abortion and its far-reaching implications. Whether students are interested in argumentative essays that engage in ethical, legal, or societal debates or research papers that delve into medical, historical, or international perspectives, this collection offers a wealth of potential topics to ignite their curiosity and challenge their thinking.

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

Find anything you save across the site in your account

How the Right to Legal Abortion Changed the Arc of All Women’s Lives

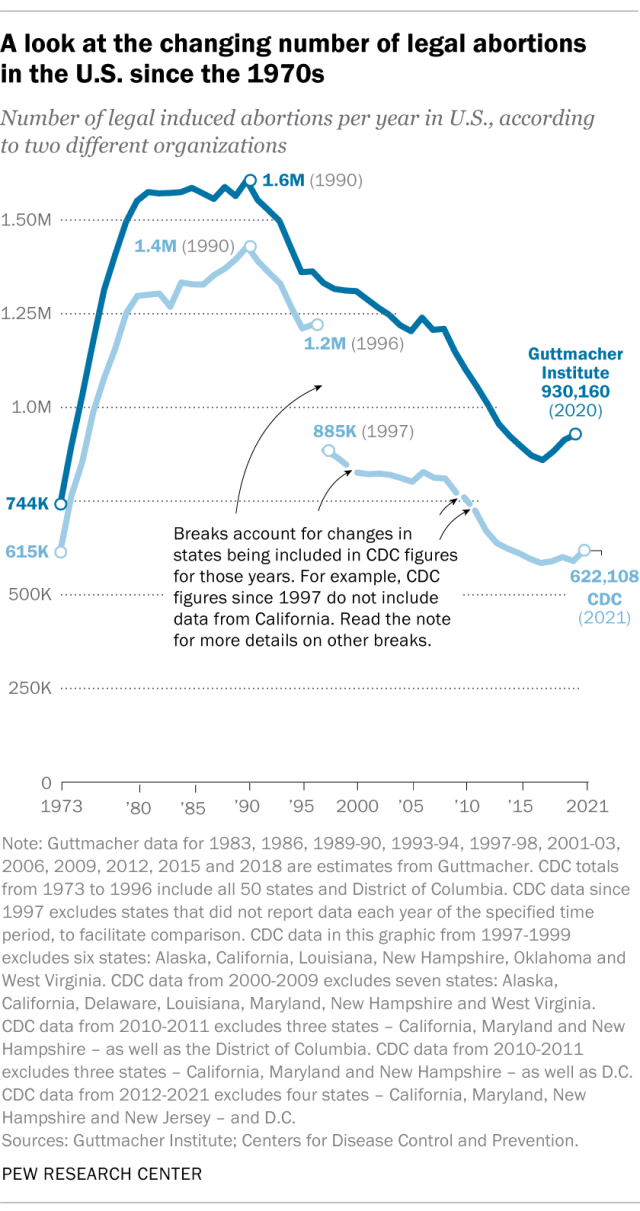

By Katha Pollitt

I’ve never had an abortion. In this, I am like most American women. A frequently quoted statistic from a recent study by the Guttmacher Institute, which reports that one in four women will have an abortion before the age of forty-five, may strike you as high, but it means that a large majority of women never need to end a pregnancy. (Indeed, the abortion rate has been declining for decades, although it’s disputed how much of that decrease is due to better birth control, and wider use of it, and how much to restrictions that have made abortions much harder to get.) Now that the Supreme Court seems likely to overturn Roe v. Wade sometime in the next few years—Alabama has passed a near-total ban on abortion, and Ohio, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Missouri have passed “heartbeat” bills that, in effect, ban abortion later than six weeks of pregnancy, and any of these laws, or similar ones, could prove the catalyst—I wonder if women who have never needed to undergo the procedure, and perhaps believe that they never will, realize the many ways that the legal right to abortion has undergirded their lives.

Legal abortion means that the law recognizes a woman as a person. It says that she belongs to herself. Most obviously, it means that a woman has a safe recourse if she becomes pregnant as a result of being raped. (Believe it or not, in some states, the law allows a rapist to sue for custody or visitation rights.) It means that doctors no longer need to deny treatment to pregnant women with certain serious conditions—cancer, heart disease, kidney disease—until after they’ve given birth, by which time their health may have deteriorated irretrievably. And it means that non-Catholic hospitals can treat a woman promptly if she is having a miscarriage. (If she goes to a Catholic hospital, she may have to wait until the embryo or fetus dies. In one hospital, in Ireland, such a delay led to the death of a woman named Savita Halappanavar, who contracted septicemia. Her case spurred a movement to repeal that country’s constitutional amendment banning abortion.)

The legalization of abortion, though, has had broader and more subtle effects than limiting damage in these grave but relatively uncommon scenarios. The revolutionary advances made in the social status of American women during the nineteen-seventies are generally attributed to the availability of oral contraception, which came on the market in 1960. But, according to a 2017 study by the economist Caitlin Knowles Myers, “The Power of Abortion Policy: Re-Examining the Effects of Young Women’s Access to Reproductive Control,” published in the Journal of Political Economy , the effects of the Pill were offset by the fact that more teens and women were having sex, and so birth-control failure affected more people. Complicating the conventional wisdom that oral contraception made sex risk-free for all, the Pill was also not easy for many women to get. Restrictive laws in some states barred it for unmarried women and for women under the age of twenty-one. The Roe decision, in 1973, afforded thousands upon thousands of teen-agers a chance to avoid early marriage and motherhood. Myers writes, “Policies governing access to the pill had little if any effect on the average probabilities of marrying and giving birth at a young age. In contrast, policy environments in which abortion was legal and readily accessible by young women are estimated to have caused a 34 percent reduction in first births, a 19 percent reduction in first marriages, and a 63 percent reduction in ‘shotgun marriages’ prior to age 19.”

Access to legal abortion, whether as a backup to birth control or not, meant that women, like men, could have a sexual life without risking their future. A woman could plan her life without having to consider that it could be derailed by a single sperm. She could dream bigger dreams. Under the old rules, inculcated from girlhood, if a woman got pregnant at a young age, she married her boyfriend; and, expecting early marriage and kids, she wouldn’t have invested too heavily in her education in any case, and she would have chosen work that she could drop in and out of as family demands required.

In 1970, the average age of first-time American mothers was younger than twenty-two. Today, more women postpone marriage until they are ready for it. (Early marriages are notoriously unstable, so, if you’re glad that the divorce rate is down, you can, in part, thank Roe.) Women can also postpone childbearing until they are prepared for it, which takes some serious doing in a country that lacks paid parental leave and affordable childcare, and where discrimination against pregnant women and mothers is still widespread. For all the hand-wringing about lower birth rates, most women— eighty-six per cent of them —still become mothers. They just do it later, and have fewer children.

Most women don’t enter fields that require years of graduate-school education, but all women have benefitted from having larger numbers of women in those fields. It was female lawyers, for example, who brought cases that opened up good blue-collar jobs to women. Without more women obtaining law degrees, would men still be shaping all our legislation? Without the large numbers of women who have entered the medical professions, would psychiatrists still be telling women that they suffered from penis envy and were masochistic by nature? Would women still routinely undergo unnecessary hysterectomies? Without increased numbers of women in academia, and without the new field of women’s studies, would children still be taught, as I was, that, a hundred years ago this month, Woodrow Wilson “gave” women the vote? There has been a revolution in every field, and the women in those fields have led it.

It is frequently pointed out that the states passing abortion restrictions and bans are states where women’s status remains particularly low. Take Alabama. According to one study , by almost every index—pay, workforce participation, percentage of single mothers living in poverty, mortality due to conditions such as heart disease and stroke—the state scores among the worst for women. Children don’t fare much better: according to U.S. News rankings , Alabama is the worst state for education. It also has one of the nation’s highest rates of infant mortality (only half the counties have even one ob-gyn), and it has refused to expand Medicaid, either through the Affordable Care Act or on its own. Only four women sit in Alabama’s thirty-five-member State Senate, and none of them voted for the ban. Maybe that’s why an amendment to the bill proposed by State Senator Linda Coleman-Madison was voted down. It would have provided prenatal care and medical care for a woman and child in cases where the new law prevents the woman from obtaining an abortion. Interestingly, the law allows in-vitro fertilization, a procedure that often results in the discarding of fertilized eggs. As Clyde Chambliss, the bill’s chief sponsor in the state senate, put it, “The egg in the lab doesn’t apply. It’s not in a woman. She’s not pregnant.” In other words, life only begins at conception if there’s a woman’s body to control.

Indifference to women and children isn’t an oversight. This is why calls for better sex education and wider access to birth control are non-starters, even though they have helped lower the rate of unwanted pregnancies, which is the cause of abortion. The point isn’t to prevent unwanted pregnancy. (States with strong anti-abortion laws have some of the highest rates of teen pregnancy in the country; Alabama is among them.) The point is to roll back modernity for women.

So, if women who have never had an abortion, and don’t expect to, think that the new restrictions and bans won’t affect them, they are wrong. The new laws will fall most heavily on poor women, disproportionately on women of color, who have the highest abortion rates and will be hard-pressed to travel to distant clinics.

But without legal, accessible abortion, the assumptions that have shaped all women’s lives in the past few decades—including that they, not a torn condom or a missed pill or a rapist, will decide what happens to their bodies and their futures—will change. Women and their daughters will have a harder time, and there will be plenty of people who will say that they were foolish to think that it could be otherwise.

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Jia Tolentino

By Isaac Chotiner

By Jessica Winter

University of Notre Dame

Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews

- Home ›

- Reviews ›

The Ethics of Abortion: Women's Rights, Human Life, and the Question of Justice

Christopher Kaczor, The Ethics of Abortion: Women's Rights, Human Life, and the Question of Justice , Routledge, 2011, 246 pp., $39.95 (pbk), ISBN 9780415884693.

Reviewed by Don Marquis, University of Kansas

Christopher Kaczor defends the Catholic view, or what is sometimes known as the substantial identity view, of the wrongness of abortion. This is not a religious view. It is a natural law argument. Its core is the syllogism that because all human beings have a serious right to life and because human fetuses are human beings, human fetuses have a serious right to life. A human being is a biological organism that belongs to our species. Judith Thomson's famous defense of abortion does not succeed. Therefore, abortion is wrong. The minor premise of this syllogism is a true claim in biology. With the exception of the discussion of Thomson's view, the major premise is the locus of philosophical interest.

Although I believe that Kaczor's positive defense of the major premise does not succeed, this book contains much of great value. A major portion of Kaczor's book is devoted to critical discussions of views concerning the right to life that are incompatible with the major premise of the above syllogism. Many of these discussions are of great interest and have great merit. Although some of these analyses can be found elsewhere in the extensive literature on the abortion issue, Kaczor's book contains the most complete, the most penetrating and the most up-to-date set of critiques of the arguments for abortion choice presently available. It is required reading for anyone seriously interested in the abortion issue. It is a good introduction for anyone who wishes to read a serious and thoughtful account of all of the various serious philosophical views that support the right to abortion. It deserves careful study. I certainly would not endorse every single argument in the book. Nevertheless, Kaczor's book contains much good material. I highly recommend it.

Two of Kaczor's analyses are especially important. The first concerns accounts of what it is to be a person found in the writings of Michael Tooley, Peter Singer, and Mary Anne Warren. These accounts are given in psychological terms and are intended to include in the class of persons human beings after the time of infancy and to exclude human beings prior to birth. I have been inclined to take these accounts for granted, but to question the arguments for the claim that one has the right to life if and only if one is now a person in one of these psychological senses. However, Kaczor offers a thoughtful discussion in which he questions whether such accounts of being a person succeed in including everyone in the class of human beings after the time of infancy. The difficulty that Kaczor discusses concerns giving an adequate and non-arbitrary account of the capacity to exhibit psychological traits that, on the one hand, excludes fetuses and, on the other hand, includes all of those individuals past infancy who have the right to life. Kaczor shows that this task is harder than it seems. Kaczor's discussion constitutes yet another serious challenge to all those philosophers who wish to defend abortion choice by appealing to the claim that fetuses are not yet persons.

Also of particular interest and merit is Kaczor's discussion of the dualistic views Tooley and Jeff McMahan have defended at great length in recent years. Both defend the claim that, because we are essentially persons, we are essentially brains capable of thought. This brain essentialism implies that we did not come into existence until the last part of pregnancy. Kaczor draws on the writings of David Hershenov, Eric Olson, and Matthew Liao to construct a critique of this brain essentialist view. Kaczor's analysis of brain essentialism is a forceful critique of the Tooley-McMahan view. Furthermore, it is a nice summary of the best of the recent literature critical of brain essentialism. This book is worth reading just for this incisive account.

Kaczor's book is organized in the following way. Kaczor treats 'is a person' as synonymous with 'has a serious right to life'. Kaczor's book is divided into chapters most of which have titles of the form "Does Personhood Begin at X?" Substitution instances of 'at X' are 'after birth' 'at birth' 'during pregnancy' 'at conception' 'when the product of conception is no longer an embryo'. He also discusses Thomson's famous defense of abortion and "hard cases". A final chapter is concerned with artificial wombs.

Of course, it is not at all surprising that a book on abortion written by an author in the Catholic tradition should have this organization, but it is less than optimal. One problem is that the term 'person' has become fixed in the mind of philosophers familiar with the philosophical pro-choice tradition as having roughly the meaning that Mary Anne Warren famously attributed to it. To adopt another use of 'person' for the architecture of one's book appears to build a bias into one's analysis. The other problem is that much of this book is concerned with critical analyses of the views of others, and the views of others often don't fit well into the categories outlined by Kaczor's chapters. However, these complaints are -- in the final analysis -- matters of presentation only and such matters do not need to get in the way of the pleasure one can receive from reading this fine book.

Kaczor's positive defense of the claim that all human beings have the right to life is weaker than the rest of the book. On the one hand, to those not familiar with the philosophical literature on abortion, this proposition seems an obvious, and widely accepted, moral truth. It is, no doubt, difficult to forego the obvious rhetorical advantage obtained by basing one's view on this widely accepted claim. On the other hand, this claim has been subjected to two major criticisms, both set out clearly by Peter Singer over thirty years ago in Practical Ethics , and both discussed by Kaczor. The first can be called 'the speciesism objection'. 'Human being' is a biological concept. The wrongness of racism and sexism is based on the fact that biological properties have, all by themselves, no moral significance whatsoever. If this is so, then it seems to follow that the biological property of being a member of our species has no moral significance whatsoever, unless we equivocate on some notion like 'truly human'.

Kaczor calls the second criticism 'the over-commitment objection'. The claim that all human beings have a serious right to life seems to imply that a human being who is in an irreversibly unconscious state, such as an anencephalic child or someone who has experienced severe trauma to her brain or is totally brain dead, has a serious right to life. It certainly seems counterintuitive to suppose that it would be as wrong to end the life of such a human being as it would be to end the life of you or me. Indeed, perhaps it is not wrong at all. There is a basis for this intuition. Most of you do not believe that, if you were in such a state, an action or an inaction that would end your life would result in a diminution of your life prospects you would ever care about. Any serious defense of Kaczor's major premise requires dealing with these standard objections. Kaczor tries to deal with them. Is he successful?

Kaczor deals with the speciesism objection by offering a number of arguments. First, he appeals to the argument that since there are no other ethically relevant differences between ourselves and younger humans, and since we have the right to life, all human beings have the right to life. However, such an argument by elimination is hardly a firm foundation for a position that flies in the face of the important value of reproductive choice. After all, how can we be sure that we have surveyed all of the other potentially ethically relevant differences? Second, Kaczor treats the speciesism objection as merely linguistic. However, this suggests only that he has not come to grips with its strongest version. Third, Kaczor argues that the right to life must be based upon endowment, not performance. What people are capable of doing comes in degrees. This is incompatible with our commitment to human equality. Therefore, the right to life must be based on our endowment, on the genetics that we have in common with all other human beings. This, I am afraid, looks a good deal like the earlier argument by elimination that is surely insufficient as a basis for the right to life. Furthermore, one wonders why the right to life cannot be an equal right that one obtains by meeting some performance threshold, just as all students who pass their junior year in high school have the equal right to enroll for their senior year, whether they passed their junior year with flying colors or barely eked out passing grades.

Kaczor's strongest argument appeals to what he describes as the orientation of all human beings toward freedom and reason. The virtue of this move is that it gets our values into the account of the basis for our rights. The trouble with this move is that either this orientation is entirely a matter of the genetics that make us members of the human species or it is not. On the one hand, if it is just a matter of our human genetics, then, perhaps, it may yield the equality of all human beings. The trouble is that some individuals who are genetically enough like us to be counted as humans, such as the irreversibly unconscious, are not capable of freedom and reason. Therefore, the human genetics criterion divorces Kaczor's criterion of the right to life from the fact that as humans we (typically) value freedom and reason. On the other hand, if our orientation toward freedom and reason depends upon factors other than our genetic code, then we can retain a value-based criterion for the right to life, but anencephalic human beings, the severely retarded and severely demented, and those who have suffered the fate of being rendered irreversibly unconscious will lack the right to life. Therefore, it will be false that all humans have the right to life. The claim that our species is defined as the class of rational animals only avoids this problem by a shallow linguistic move. Each human who is irreversibly unconscious is, after all, a member of a species, the typical members of which are rational animals, even if she is not herself a rational animal. This point can be put in the following way. We can distinguish between those who are directly and those who are indirectly rational animals. A successful argument will not rest on obscuring this distinction.

Of course, the difficulty to which I am referring is what Kaczor calls 'the over-commitment objection'. (116-119). If all humans have the right to life, then we seem to be committed to too much. Kaczor's responses to this objection are sketchy at best. He suggests that one might want to hold that "the right to life is an alienable right, or that neocortical death should be defined as death or that human beings in permanent comas have a different right to life than human beings in temporary comas." (119) He concludes that the view that all human beings have the right to life does not necessarily lead to the view that it is wrong to end the lives of those who cannot be characterized directly as rational animals.

This is an almost unbelievably weak response to what Kaczor recognizes is one of the major objections to his positive account of the right to life. It certainly will not persuade those who wonder whether Kaczor's appeal to equality considerations to justify the right to life of all human beings is consistent with the view that the permanently comatose may have a different (read 'lesser') right to life than the rest of us. It will certainly not persuade those who agree with the orthodox Vatican view that not to provide ordinary care, such as food and water, to any human being, no matter how profoundly disabled, is intentionally to end an innocent human life and is, therefore, wrong. It will certainly not persuade anyone who is convinced (as I am) by the arguments of Alan Shewmon that the death of the brain is not sufficient for the death of a human being. It will not persuade anyone who recognizes that the arguments for the neocortical definition of death depend on the doctrine of brain essentialism, a doctrine Kaczor so emphatically rejects.

Even if all of these difficulties survive analysis, it does not follow that abortion is morally permissible. Nevertheless, it does imply that the major premise of the syllogism that Kaczor endorses as the basis for his view should be rejected. Kaczor's weak arguments are not a sufficient basis for overriding the important value of reproductive choice.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

5.1: Arguments Against Abortion

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 35918

- Nathan Nobis & Kristina Grob

- Morehouse College & University of South Carolina Sumter via Open Philosophy Press

We will begin with arguments for the conclusion that abortion is generally wrong , perhaps nearly always wrong . These can be seen as reasons to believe fetuses have the “right to life” or are otherwise seriously wrong to kill.

5.1.1 Fetuses are human

First, there is the claim that fetuses are “human” and so abortion is wrong. People sometimes debate whether fetuses are human , but fetuses found in (human) women clearly are biologically human : they aren’t cats or dogs. And so we have this argument, with a clearly true first premise:

Fetuses are biologically human.

All things that are biologically human are wrong to kill.

Therefore, fetuses are wrong to kill.

The second premise, however, is false, as easy counterexamples show. Consider some random living biologically human cells or tissues in a petri dish. It wouldn’t be wrong at all to wash those cells or tissues down the drain, killing them; scratching yourself or shaving might kill some biologically human skin cells, but that’s not wrong; a tumor might be biologically human, but not wrong to kill. So just because something is biologically human, that does not at all mean it’s wrong to kill that thing. We saw this same point about what’s merely biologically alive.

This suggests a deficiency in some common understandings of the important idea of “human rights.” “Human rights” are sometimes described as rights someone has just because they are human or simply in virtue of being human .

But the human cells in the petri dish above don’t have “human rights” and a human heart wouldn’t have “human rights” either. Many examples would make it clear that merely being biologically human doesn’t give something human rights. And many human rights advocates do not think that abortion is wrong, despite recognizing that (human) fetuses are biologically human.

The problem about what is often said about human rights is that people often do not think about what makes human beings have rights or why we have them, when we have them. The common explanation, that we have (human) rights just because we are (biologically) human , is incorrect, as the above discussion makes clear. This misunderstanding of the basis or foundation of human rights is problematic because it leads to a widespread, misplaced fixation on whether fetuses are merely biologically “human” and the mistaken thought that if they are, they have “human rights.” To address this problem, we need to identify better, more fundamental, explanations why we have rights, or why killing us is generally wrong, and see how those explanations might apply to fetuses, as we are doing here.

It might be that when people appeal to the importance and value of being “human,” the concern isn’t our biology itself, but the psychological characteristics that many human beings have: consciousness, awareness, feelings and so on. We will discuss this different meaning of “human” below. This meaning of “human” might be better expressed as conscious being , or “person,” or human person. This might be what people have in mind when they argue that fetuses aren’t even “human.”

Human rights are vitally important, and we would do better if we spoke in terms of “conscious-being rights” or “person-rights,” not “human rights.” This more accurate and informed understanding and terminology would help address human rights issues in general, and help us better think through ethical questions about biologically human embryos and fetuses.

5.1.2 Fetuses are human beings

Some respond to the arguments above—against the significance of being merely biologically human—by observing that fetuses aren’t just mere human cells, but are organized in ways that make them beings or organisms . (A kidney is part of a “being,” but the “being” is the whole organism.) That suggests this argument:

Fetuses are human beings or organisms .

All human beings or organisms are wrong to kill.

Therefore, fetuses are wrong to kill, so abortion is wrong.

The first premise is true: fetuses are dependent beings, but dependent beings are still beings.

The second premise, however, is the challenge, in terms of providing good reasons to accept it. Clearly many human beings or organisms are wrong to kill, or wrong to kill unless there’s a good reason that would justify that killing, e.g., self-defense. (This is often described by philosophers as us being prima facie wrong to kill, in contrast to absolutely or necessarily wrong to kill.) Why is this though? What makes us wrong to kill? And do these answers suggest that all human beings or organisms are wrong to kill?

Above it was argued that we are wrong to kill because we are conscious and feeling: we are aware of the world, have feelings and our perspectives can go better or worse for us —we can be harmed— and that’s what makes killing us wrong. It may also sometimes be not wrong to let us die, and perhaps even kill us, if we come to completely and permanently lacking consciousness, say from major brain damage or a coma, since we can’t be harmed by death anymore: we might even be described as dead in the sense of being “brain dead.” 10