An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Narrative Health: Using Story to Explore Definitions of Health and Address Bias in Health Care

Emmalee pallai.

1 Community University Health Care Center, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis

When defining health and illness, we often look to governing bodies such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization rather than our communities. With health disparities prominent throughout the US, it is important to look at the structures we have set forth in health care and find new ways to address health as well as new definitions. Storytelling is a valuable tool to help understand how our communities address health and the place of the hospital or clinic in their health. Narrative Health focuses not just on storytelling but also story listening. At the Community-University Health Care Center in Minneapolis, MN, we have implemented narrative health programs with patients and learners from various health professions. Using creative writing pedagogy and techniques to decentralize the practitioner-patient binary of illness, we learn about our patients’ stories of health and experiences with health care. It is important to move past the definitions of health to the complexities of story that allow for the human aspects of illness to be absorbed and understood.

INTRODUCTION

When speaking about health, we need to broaden our parameters and define health in a way that includes the social determinants of health, that is, those elements of health that are structuralized and take into account geographic regions of people, their work, age, education level, race/ethnicity, sex, gender, and numerous other elements of a person’s life. The role of a health care center, such as a clinic or hospital, is limited in a community. Health care centers must find ways to build relationships in the surrounding communities to better understand the needs of those communities and how the health care centers can best meet those needs.

America has one of the largest income-related health disparities in the world regarding patients’ past experiences and future access to care, 1 and in Minnesota there are persistent health inequities along lines of race, economic status, sexual identity, disability, and geographical location. 2 To begin to address these inequities, we must look at the structures that created them and listen to our communities and the stories they tell about how they define health and the clinic’s place in their health. Storytelling is a useful tool that crosses ethnic delineations and is a powerful way to begin understanding how to address inequities and bias in health care.

Storytelling is well used in medicine and other professions to help connect practitioners to their clinical practice on a more emotional and empathetic level. Sometimes situated in medical humanities or called narrative medicine, a term coined by Rita Charon 3 in the early 2000s, storytelling in medicine is presented as a means to bring back the communication stream often lost between physician and patient. Rita Charon defines narrative medicine as “medicine practiced with narrative skills or recognizing, absorbing, interpreting, and being moved by stories of illness.” 3 Although narrative competence and skills are important, we need to move past the idea that health is completely encompassed by the realm of medical practice. By focusing on people in communities, we can begin to understand social determinants of health and paths to health equity. We must listen to the stories of those in the community, their definitions of health, and the issues they see as important to the health of individuals, and the health of their community. Thus, we need to move past narrative medicine and toward narrative health.

HISTORY OF DEFINING HEALTH

The World Health Organization defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” 4 This definition is the first principle in the preamble to the World Health Organization’s constitution, which was ratified in 1948. 4 Health disparities, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, are “preventable differences in the burden of disease, injury, violence, or in opportunities to achieve optimal health experienced by socially disadvantaged racial, ethnic, and other population groups, and communities.” 5 However, these definitions of health and disparities were likely not created in the communities to which they are applied. The community where we work, the Phillips neighborhood of Minneapolis, MN, is an economically and ethnically varied area with many new refugees and immigrants. The Community-University Health Care Center (CUHCC) is bordered by both the Indian Health Board and the Native American Community Center. CUHCC has one of the most ethnically diverse patient bases in the area, with a high number of patients who are Somali or of other African descent, African American, Hispanic/Latino, and Asian American (Hmong, Vietnamese, and others). Only 17% of our patients are of European descent as of the 2016 Uniform Data Systems data. If we reached out to our communities to define health, would it match that of the World Health Organization? When speaking of health disparity, would our tight-knit communities feel socially disadvantaged?

These questions are especially important when we discuss health equity and equity in general. When we speak in definitions and those definitions are created by a dominant group, we are speaking in a very denotative, or literal, manner. This flattens and removes the complexities involved within an issue. The idea of the sound bite definition, or oversimplification to garner interest, as it is used in marketing and the media, has led to a loss of understanding and pushing beyond the one-liner to better define, and thus address, a problem. 6 In simplifying these problems for a mass audience, the media also leave out entire groups of people who may be in more dire need of intervention or prevention. This shifts focus to the negatives of a problem and does not explore the ways people can prevent, identify, or deal with the issue together. 7 For example, although much has been researched and discussed in journal articles about the current opioid crisis, information in the popular media such as news broadcasts and newsstand magazines focuses on the numbers of people who are overdosing, but not as often on prescription practices or underlying issues, including mental health and loneliness, that lead to substance abuse. By simplifying the language used, we lose the meaning behind words. Words have both a denotative and connotative meaning. Through storytelling, one reunites words with their connotative meaning, focusing on the language and emotions to create stronger understanding. When speaking of health equity and disparities, we need to speak with history and emotive awareness. To do that, we move to story.

Storytelling is unique in bringing contextual relations between various areas important to the storyteller. 8 It allows the storyteller to connect their physical health to their mental, social, religious, and other realms of health providing a holistic approach. This provides a wealth of data about perceptions of equality, either directly through the story or indirectly through the ways in which they physically tell the story such as tone of voice and body movement. 9 For many of CUHCC’s patients who come from countries with oral traditions, such as Somalia, storytelling—and more importantly story listening—is a way to access definitions of health in our community along with how the community views realms of health and how to partner with health care centers. Story is also an important tool in historically underserved populations, which are often not heard in modern medicine or have their form of healing viewed as alternative or complementary medicine. In addition, the ever-increasing number of foreign medical graduates practicing in the US bring their own culture and language into practice and communication with patients. Storytelling networks are important to increase civic engagement, enhance a sense of belonging, and reach audiences left out of modern mass media. 7 This is why the move toward narrative health is important. Narrative health asks us to thoughtfully examine who is telling a story and how they are telling the story (with a focus on how and who is defining health), to listen intentionally, and to share stories both between and within communities.

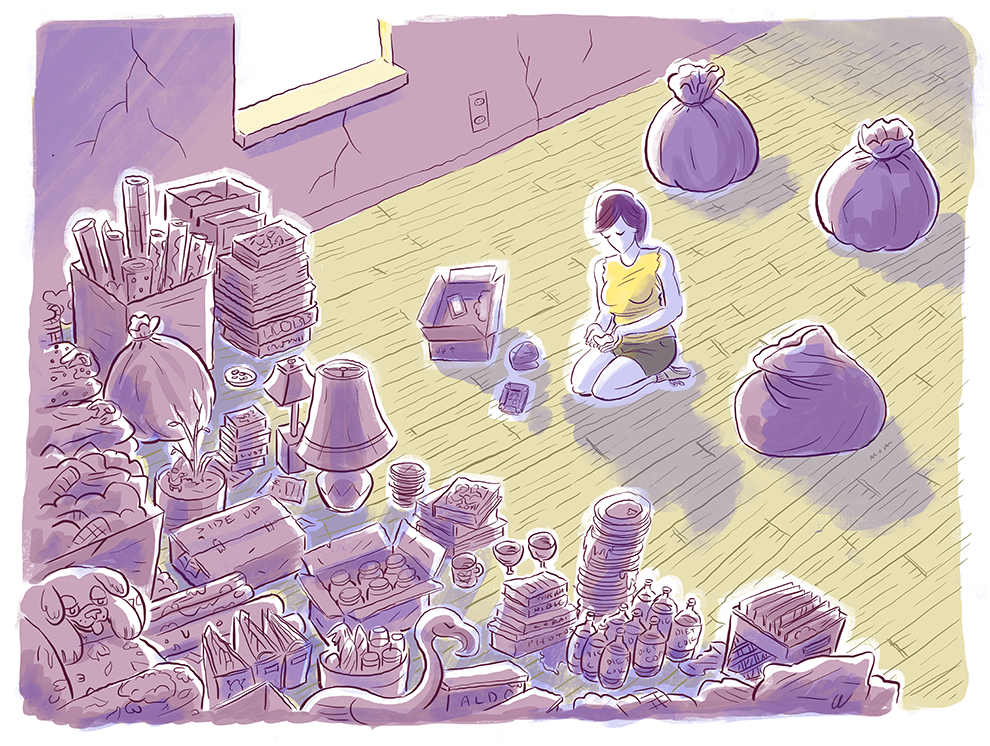

THE MOVE TOWARD NARRATIVE HEALTH: E PALLAI’S STORY

My family—mother, brother, and cat—and I were homeless for part of my childhood. We lived in a tent, going from state to state, before settling in New York, where we lived in a garage. Even before then, before our items were sold and we packed everything into a car to spend time on the road, a modern-day Joad family looking for work, we were struggling. I remember our main meals coming from the school lunch program. I remember going to the grocery store garbage bin at night to supplement what food stamps provided.

There are many reasons that lead people and children into homelessness. Even though I lived through being homeless as a child, I will never fully understand all the complexities that led us there. What I do remember thinking would help us was, “If I only had a voice.”

In school we take English class to strengthen our voice so other people can hear us. I was put in speech therapy to remove my accent (or lisp depending on who is telling the story), and to further strengthen my voice. That phrase, “strengthen your voice,” was heard a lot, and I still hear it today. It’s what led me to become an English teacher—to help others strengthen their voices as I had, so they could get a good job and be heard. I wanted to help others by teaching them to speak and write properly. Thankfully, I learned this approach is wrong when looking at the core of what I wanted to do—help people be heard and ease their suffering.

In learning to strengthen my voice, my history was erased from my speech. As I continued to grow, going to high school and then getting a scholarship in another city, I became alienated from friends and family who thought I was abandoning them. I had to code-switch among groups of friends, and there were those who felt I no longer could understand them because of how I spoke. In telling those who were as disadvantaged as I was in childhood that to be heard they needed to speak like others, as I was now doing, like those outside their communities, I was helping to alienate. When we tell people to strengthen their voices, we are telling them we are not ready to listen to them where they are. Indeed, that we won’t listen until they speak in a manner closer to ours. It is the difference between asking someone to assimilate and become like us rather than integration, which requires compromise on both sides. We are adding another layer of burden on those who are so terribly burdened to begin with.

This is not to say that English as a Second Language classes and other initiatives are not helpful, but that when approaching our communities, our number one focus should be to listen intentionally and purposefully without judgment of language and traditions in their storytelling. This is what led me to move past narrative medicine and to look for a new paradigm, a new word to encompass how important it is to listen to who is defining health in a community and to mutually share stories, not have medicine and communities stand on opposite sides of the room. To understand something as complex as health, we can not only listen or not only speak. We need a circle where we share and listen freely and synthesize our ideas of health with others as equals.

PRACTICING NARRATIVE HEALTH

We must fully acknowledge the sound-bite nature of any word that talks about storytelling. The need to market to professionals requires a phrase that can be used in pitch sessions to practitioners, directors, deans, and others involved in health care. The term narrative health was developed to encompass the aspects of an interprofessional community outside just medicine, one that includes the community and patient as a vital part of our learning and stories. At CUHCC we conduct 2 Narrative Health workshops: 1 with learners only and 1 with patients and learners together. When speaking with patients, we discussed the idea of narrative health in earlier sessions but now have changed to call it storytelling or just narrative workshops. We also focus on calling our patients “community members” during these workshops, to mitigate the practitioner-patient power structure. For ease of this article, we will continue to use the term patients.

Learner-Only Workshops

As part of the University of Minnesota, CUHCC is home to a number of “learners” (students in the health professions) for their continuity clinics, internships, or clinical rotations. Learner-only sessions offer a place for an interprofessional group of students and residents to discuss health issues together while exploring the intersections of their growing professional identities. In these sessions learners read a selected piece of writing ahead of time to discuss with the group before working on a guided writing assignment. Readings vary, from selections from graphic novels and memoirs, to short stories, case studies, and poems. Care is given to include readings from authors of diverse backgrounds. Selections from anthologies such as Beauty is a Verb: The New Poetry of Disability, 10 Women Write Their Bodies: Stories of Illness and Healing, 11 Healing by Heart: Clinical and Ethical Case Stories of Hmong Families and Western Providers, 12 and The Remedy: Queer and Trans Voices on Health and Health Care, 13 along with writings by authors such as Sherman Alexie and Lynda Barry, are explored through a creative writing lens. We first discuss the readings as elements of literature and what drew us in as readers, before we talk about the implications to health care and development as a practitioner. For example, when reading Sherman Alexie’s 14 short story, “What You Pawn I will Redeem,” we opened with general thoughts about the writing style, the winding narrative, and initial reactions. We talked about the frustrations of narrative styles that occur in differing populations, and then we discussed experiences during patient encounters that mirror the protagonist’s narration. This led to us debating how information was relayed in the story, and in real-life encounters, vs what learners are taught in their respective schools. From there, the discussion moved to social determinants of health—those presented in the story and those that might lead a patient to “noncompliance.”

We approach the writing section from a creative writing model that involves 2 to 4 prewriting questions before beginning the final product. This helps the learners get past the initial response to their reflection and learn more about themselves, language, and how others use language. They may be asked to try a different narrative style, or write a poem, or write from their patient’s point of view. They are also asked to explore times when they were ill, to connect themselves with not just their patients but also times when they themselves were a patient. By using creative writing modalities, we can gain the benefits of reflection, bringing in empathetic models and recognizing we are all part of the culture of illness. We also gain the benefits of creative writing, which include language usage, differences in tone and mood, and other aspects important to story. 15

Learner and Patient Workshops

In these sessions CUHCC patients and learners are paired for a story writing exercise. Learners are instructed beforehand that they are to listen to the patient and to help as the patient instructs. In some cases this means being a scribe and asking probing questions focused on the patient’s story. That is, to focus on the sensory events being told rather than the medical ones, such as how it felt to lie on the gurney in terms of physical sensations (cold metal, straps too tight, or itchy) and emotions. Learners are not to diagnose, but simply to listen. If the patient does not want to work with a learner, the learner writes his/her own story alongside the patient.

We begin with a reading that is short and read it aloud. These can be published materials, or one written by a group member in a prior session. Much like the learner sessions, we discuss the reading as a group before going into our prewriting, leading to the final product. At the end, everyone is encouraged to share their stories. We discuss what we liked and want to know more about vs comparison or diagnosis of illness. We also discuss the way language is used. Learners are encouraged to share alongside the patients.

We do not limit the writing to English. One of our more impactful sessions included a Somali man who brought a poem he wanted to share about battling his addiction. He read it in Somali, and those who understood the language were moved to tears. We had a group member who served as a Somali interpreter say it was too beautiful and complex a poem to translate into English. The emotions were raw and visible in people’s reactions, leading us to comment on how moving it was despite not speaking the language. A debrief with learners later led to a discussion about how this mirrors what happens in the clinic on a daily basis. Often patients who do not speak English come into the examination room, and we need to understand each other, with or without an interpreter. It also gave us a chance to reinforce that a community does not have to speak the same language. We are a community connected by health and illness, linking us in a common humanity.

Benefits of Narrative Health Workshops

Narrative Health workshops were initially conceived as an educational intervention to teach future health care practitioners varying ways of communicating with a focus on listening. It was also meant to broaden their understanding of how health is discussed and defined by providing a number of voices, often underrepresented in their education. One of the themes we are seeing in our patients’ writing is how they feel healthy when connected to other people and their community, such as in Ishmael Amin’s story in which he is happy eating Somali food with a friend, or in Michael Southard’s story in which we learn how being placed in an Indian Boarding School for Native Americans as a child still affects him today (see Supplement: Patient and Learner Stories). This expands the medical view of health from residing inside the body to the wider community.

Comments from learners include the following: [The Narrative Health workshop] helps me to slow down and listen to my patients’ stories to help me cooperate with my patient to create a better therapeutic plan; [it] made me think differently about how patients perceive what I consider good care. I remember hearing a story about a procedure that I thought was so great [but] that the patient found disorienting and terrible, and I think it helped decrease the differing power dynamics between patient and provider.

An added benefit is that it also promotes learner wellness by having a dedicated space for reflection and to discuss developing identities outside the technical, or denotative, realms of their professions. We have found this reconnects students in the human aspects of health care. So often in health professions the scientific aspects are addressed, but the personal and humanitarian aspects, when discussed at all, are given less weight. These sessions, particularly the patient/learner ones, have helped facilitate learning from lived experience in addition to books or simulated experiences.

Patients in the workshops have discussed feeling empowered to speak about their health without worry of diagnosis or practitioner agenda. Some have said that within the group setting, it feels like therapy to have a space to be heard. Others find that the act of writing the story, even if not shared, still helps. On the clinical side, practitioners whose patients have attended said they learned things in their patients’ writings they had not learned after 2 years of working with them. Although we do not share patients’ writing with their practitioners, the patient sometimes brings it to an appointment to share. Patients have even brought in writing to share with the group that they had continued to refine at home after a prior workshop. Through this, we are creating a community, learning to listen to all of our definitions of health, and strengthening that first step toward health equity—acknowledging that the voices and experiences of others are important and must be heard so we can find solutions together.

Narrative Health workshops at CUHCC have helped us and our learners open lines of communication with our communities and better understand their social determinants of health. Through patient and learner sessions we are learning more about the variety of voices in our community. We are also providing an open forum for listening, an often forgotten or not explicitly discussed part of communication, and empowering patients. By holding these sessions in authentic language and voices, learners can access the emotional aspects of language and health care. This has allowed us to teach the next generation of health practitioners the importance of narrative health and of listening to their community, one they are a part of, and how health is truly defined by our patients and even ourselves, as we are not outside the humanity of health and illness.

We have much room for growth in our program. We would like to expand to involve other community centers and more members of the community. By bringing narrative health to the community and outside the clinic, we can also gain a better idea of where our place is in the greater community. We would also like to see more staff involvement so the lessons learned are not just for our health care students, but for everyone in CUHCC. Another aspect we would like to explore is collecting these stories for a wider audience to see how the voices of our community define health. We want to have their stories stand alongside the more dominant voices in health care—those of the physicians, other practitioners, and bigger organizations that define not just health and health care but also access to those services and what is necessary. In those ways, we hope to expand narrative health to better understand and address health disparities in Minnesota and beyond.

Supplement: Patient and Learner Stories

When writing in Narrative Health workshops at Community-University Health Care Center (CUHCC) in Minneapolis, MN, patients are guided through writing prompts asking them to write about a “moment” on their health journey. Narrative styles differ greatly among our patients and cultural backgrounds. We honor their stories as they have shared them with us and provided a cross section of our population.

A MOMENT ON THE HEALTH JOURNEY

Below, a patient writes about getting a diagnosis and beginning to address her illness after 11 years of living with it .

By Christine Hoey, CUHCC Patient

Nervously waiting, listing all my symptoms. Answering questions very few have previously asked. Feeling heard by the right Drs and told what I had finally. Hearing steps to be taken next. Dr observing every movement and noting what movements were. Checking thoroughly and a diagnosis finally! I know what I have and can finally address what can help and learn to live with what can’t be controlled. And today it snowed! 1st in 34 years for me and it made it a beautiful day.

Fear and anxiety alleviated and better health is the goal.

SENSORY ASPECTS OF ILLNESS

In this prompt, participants were asked to focus on the sensory aspects of an illness they had. Here, a pharmacy resident writes about nasal surgery

Scents of Home

By Ajay Patel, Pharmacy Resident, 2017

The pressure of metal tweezers, Reaching far in. Plastic sliding down my skin. Fluid, gushing out with no end.

Clang of metal on metal Tweezers fall to the tray, Holding a plastic splint, Covered in thick obstructive mucus, Streaked with black, lined with blood.

The deep grumble of his voice, “How does that feel?”

Air rushes in. My lungs feel full for the first time. High on oxygen. Giddiness.

I return home, Elated by the return of a long-lost sense Overwhelmed at what I’ve been missing. A room full of smoke from burning incense, Comforting and familiar. A tingling burn gives new happiness to an old comfort.

A “MAGIC LANTERN”: EMOTIONAL SUPPORT

In this session, learners were to write about a “magic lantern’” something they have imbued with special powers and look to for emotional support. Here, a pharmacy resident writes about her hairclip

Little Black Clip

By Dema Mohammed, Pharmacy Resident 2018

A black hair clip that looks like any other, a little bigger than most but smaller than the biggest. It has a few gems on it, a couple missing. It takes me back to the time it went missing. I was so hung up on trying to find it. You see, this hair clip was unlike any other. It’s the only hair clip that has lasted its time, it’s the only one that can hold up my hair in one try. I need it with me for without it I feel lost. Some days when I don’t feel strong, I rely on my hair clip for seeing how small it is but thinking about what it can do gives me hope. After I had lost it and found it I would never lose it again. It needs to be in sight, clipped onto something I would have with me for those times in need where I’ve had enough when I want to just throw my hair up and feel comfort. All of this from a hair clip, one unlike any other, my hair clip.

MEMORIES OF MENTAL ILLNESS

Here one of our patients, prompted to write about a moment on her health journey with a focus on the sensory experiences of the moment, writes about the day she was committed to a psychiatric unit.

By Uma Oswald, CUHCC Patient

It was a sad little square room. The door was thick and heavy as it clanked shut behind me. It was locked—I heard the door lock. Feeling slightly frightened, like a caged bird, I walked over to the makeshift hospital bed—it was on wheels—and curled up in the fetal position, hiding under the blanket like a child. The lights were dim—I wanted them off, so the blackness would consume me and I could pretend I was somewhere else. The harsh light, the only bright spot in the room, came from the sliver of a window on the door that was connected to the doctor’s office. I knocked and the doctor, a petite woman opened the door. Of little I could see of the office, it was a whole other world. “I’m feeling okay. You know I really don’t think I need to be here.” She knew I was lying. She said I had to stay. So much for a quick escape.

I went back to the bed, and somehow, sleep overtook me. I did not know what time it was when they came for me. It was the damn doctor and a male and female EMT. They strapped me to a gurney. I tried not to shake. I was trying to be brave. I smiled and conversed with the Euro EMTs. I laughed.

I did not know where I was going, but I knew it was a psych ward, where mentally disturbed people went. I pictured a county jail cafeterialike room, surrounded by a cage, doctors on the other side, staring at us like we were monkeys.

A FAMILY MEMBER’S PERSPECTIVE

In this poem, a pharmacy resident writes about navigating the hospital for a family member’s health, her role in her family, and the ways pharmacy is utilized—hiding in pharmacy education to avoid tough emotions as well as being called on to handle the health care side of family illness because of her role as a pharmacy student.

By Morgan Stoa, Pharmacy Resident 2018

The waiting room so warm and cozy Comfy chairs, a wonderful decorated Christmas tree People waiting, last names being called When will I hear my own?

Focus on your work. Finals are this week. It will keep the worry away.

Good! You made it Where’d you park? You will have to pull around here soon

My name! How is she? How did it go? When can I see her again? Pull the car around now, please He just said so. I will walk back and get her

Cold, stale, sterile White linen sheets, small frame shaking from the cold She’s always cold Or is it the meds?

She needs socks. Well at least put the left one on now. I will drive home, just go pick up her medications.

“Why can’t you just go. You’re the pharmacy student. I don’t even know what I am looking for.”

Discharge papers, IV pulled, rolled into the winter snow Still shaking Still cold Got to get her home

Her last treatment was Monday. I was never able to go. The work and studying I used as a bandaid is now my entire life. Not just a simple tool to distract myself but my whole and complete occupation. What I wouldn’t give to go to that pharmacy.

I hope it’s at least warm. Please tell me it’s warm As warm as it can be Alone in a sterile white stale room.

POSITIVE ASPECTS OF ILLNESS

In this prompt, we were focusing on positive aspects of our health journey. Here, a Somali patient writes about coming home from the hospital.

By Ismael Amin, CUHCC Patient Practioner-Patient-Interpreter Relationship

I woke up and she was holding my hand. Her eyes filled with tears. I wondered, why she cried, the pictures showed me.

I came home and see my bed again. I like the sky, it was deep blue on my discharge day, it reminds me of the power of God. Shaking hands with friends again was a great feeling. I ate with my friend Somalian food, rice with goat meat.

Mohamed is a Somali-speaking patient at CUHCC. Here he describes what an appointment is like for him working with both a practioner and interpreter. This was written with the aid of a fellow participant who spoke Somali.

By Mohamed Yusuf, CUHCC patient

When I need treatment for diabetes, I go to the clinic here. After waiting in the waiting room, finally having your name called, and getting your vitals taken, you are left in the doctor’s room. You wait, alone. You feel lonely. When the doctor comes, they tell you your blood work—if your sugar is high or low. If it is high, you feel unhappy. You are surprised when they have to increase the medicine. The doctor sits typing at the computer, but they look you in the eye when they talk to you. The interpreter translates word by word, so you can talk in your own language, Somali. When the doctor talks they listen—then they talk to you—and you listen. Then you tell the interpreter what you want to say—and they tell the doctor. That way, they answer every question you have. Then they will tell you what to do. You all sit there, in the small little room, in three chairs. If you have back pain, there’s a place to lie down, and the doctor will examine you—here, pain? Here pain? Then she will decide what you need. They ask lots of questions, but it’s okay. You feel cared for.

REFLECTIONS ON CHANGE

Michael has been to almost every patient/learner writing session we have had. In his writing, he talks about the holidays, family, and being taken away to be put in a boarding school for Native Americans as a young child.

By Michael Southard – CUHCC Patient

When my mom and dad split up, I had to go live with my grandpa. A lot of things happen while living with him. Though the one that hurt most was having to stay in a Catholic boarding school because my grandpa did not want to raise me. He wanted his freedom. So for grade school to Jr high school, I was there. While there I got into a lot of fights because I am a half breed. And the way the boarding school try to change me (into the white man’s way of life). Not too long hair, not to speak our language, not to believing our higher power, and so on. And when holidays come I would be one of the two kids still there. Never being with my family, or relative. This is why I don’t like holidays so much. Then not knowing my own language, to speak it, then all the fights with others, even my own cousins, and so on. This is why I don’t like talking about my past because I go through so many feeling. Tough!! I got to do this in order to feel better, and work this out in a better way so I don’t feel so scared. Though I will always not liking talking about it. There is a lot more. The one I talked about is just the tip of my past … though I am working it out.

Acknowledgment

Kathleen Louden, ELS, of Louden Health Communications provided editorial assistance.

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Narrative Essay Example about The Importance of Mental Health

For many, mental health is a topic of discussion that’s avoided. Some believe that it’s very important and something that needs to be talked about. Others believe it isn’t that important or that mental illness simply isn’t real. For me, my opinion on the topic has changed over time. I used to not be very aware and did not care that much about mental health. Only until I personally was affected by it did I understand its importance.

At a young age, my grandmother passed away. Shortly thereafter, my sister left the house and cut ties with my family. I was not only grieving with the loss of my grandmother, but also not knowing where my sister was or if she was ever coming back. I was devastated, but I didn’t have time to grieve. Everyone in my household became irritable, lashing out when faced with a minor inconvenience. Talking about my feelings became difficult since nobody wanted to bring the situation up. I felt like I was on an island, with nobody around to help.

My middle school years only made things worse for me. I always felt like I was bothering someone, or that I was being a disturbance. Making friends was a challenge because of my somber demeanor. My grades were plummeting because I couldn’t find the motivation to finish my homework. Things were getting bad. Nearing the end of 8th grade, I was at my lowest low.

At this point, I knew something was wrong. I constantly felt tired, I couldn’t pay attention in class, I wasn’t motivated to do anything, and I couldn’t be bothered to do things I used to love doing like video games or sports. I talked to my mom, and she suggested that we see a therapist. I had no idea what a therapist was like since I had never been to one. To be quite honest, after looking it up I thought it was a scam. Why would I pay someone money to talk for an hour? The lady we visited changed my mind, however. She specialized in children and asked me a lot of questions right off the bat. They were things I had never been asked before. “How are things going around the house?” “How does that make you feel?” “Why do you feel unmotivated?” It felt good knowing that at least someone cared. After that, she had me do activities out of a booklet and on a laptop. Later I found out those were used to diagnose me with ADHD and Major Depressive Disorder.

While the diagnosis and the eventual use of medication helped, it didn’t solve everything. I still went to therapy and explained the way I felt. I started to gain confidence and things were looking up. I reached out to more people, involved myself with groups and clubs, and tried to stay more on top of my schoolwork. While things weren’t perfect, the progress was satisfying. Knowing that I could get through difficult times inspired me to do more and go beyond what I thought was possible. The people around me cheering me on and encouraging me to keep going made things a lot easier as well.

I have a lot of room for improvement, but I want to prove that people who are suffering from mental illnesses aren’t weak. Reaching out to others was the best thing I could have done for myself, and I want others to feel the same way. I’m grateful for all the supportive people in my life, they’ve helped me to realize how important my own mental health is. Their kindness inspires me to work through my problems instead of letting them hold me back. Only through them would I have realized how important mental health truly is.

Related Samples

- Essay Example: Why You Should Wear A Mask?

- The History of Surgery Essay Example

- Reflective Essay Sample on Leadership and Service

- Personal Narrative Essay: Experiencing in University

- Different Perspective Essay Example

- Speech On National Honor Society Induction Ceremony

- Summary of Get Good with Money by Tiffany Aliche (Essay Sample)

- Losing Weight Personal Essay Example

- Persuasive Essay on College Athletes Should Be Paid

- Harmful Effects Of Corn Essay Sample

Didn't find the perfect sample?

You can order a custom paper by our expert writers

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you’re on board with our cookie policy

- A Research Guide

- Essay Topics

- 120 Medical & Health Essay Topics

120 Medical & Health Essay Topics

Health essay topics: how to choose the perfect one.

Health Argumentative Essay Topics:

- The impact of fast food on public health

- Should the government regulate the advertising of unhealthy foods?

- The benefits and drawbacks of vaccination

- The role of genetics in determining health outcomes

- Should smoking be banned in public places?

- The effects of excessive screen time on mental and physical health

- The importance of sex education in schools

- Should the consumption of sugary beverages be taxed?

- The ethical implications of genetic engineering in healthcare

- The impact of social media on body image and mental health

- Should healthcare be a universal right?

- The benefits and risks of alternative medicine

- The role of exercise in preventing chronic diseases

- Should the government regulate the use of antibiotics in livestock?

- The impact of climate change on public health

Health Persuasive Essay Topics:

- The importance of regular exercise for overall health and well-being

- The benefits of a balanced and nutritious diet for maintaining good health

- The dangers of smoking and the need for stricter regulations on tobacco products

- The impact of excessive sugar consumption on health and the need for sugar taxes

- The benefits of mental health awareness and the importance of seeking help when needed

- The dangers of excessive alcohol consumption and the need for stricter alcohol regulations

- The importance of vaccinations in preventing the spread of diseases and protecting public health

- The impact of technology on physical and mental health and the need for digital detox

- The benefits of practicing mindfulness and meditation for stress reduction and overall well-being

- The dangers of excessive screen time and the need for limiting technology use, especially in children

- The importance of sleep for physical and mental health and the need for better sleep habits

- The benefits of regular health check-ups and preventive screenings for early disease detection

- The impact of air pollution on respiratory health and the need for stricter environmental regulations

- The benefits of breastfeeding for both the mother and the baby’s health and the need for support and education

- The dangers of sedentary lifestyles and the need for promoting physical activity in schools and workplaces

Health Compare and Contrast Essay Topics:

- Traditional medicine vs alternative medicine: A comparative analysis of their effectiveness in treating common ailments

- Vegetarianism vs veganism: Examining the health benefits and drawbacks of these two dietary choices

- Cardiovascular exercise vs strength training: Which is more effective in improving overall health and fitness?

- Mental health vs physical health: Analyzing the impact of each on overall well-being

- Organic food vs conventional food: Comparing the nutritional value and potential health risks associated with each

- Western medicine vs Eastern medicine: Exploring the differences in approach and effectiveness in treating chronic illnesses

- Smoking vs vaping: Assessing the health risks and benefits of these two forms of nicotine consumption

- High-intensity interval training (HIIT) vs steady-state cardio: Determining the most efficient method for weight loss and cardiovascular health

- Prescription medication vs natural remedies: Evaluating the effectiveness and potential side effects of each in managing common health conditions

- Physical health vs emotional health: Examining the interplay between these two aspects of well-being and their impact on overall health

- Conventional dentistry vs holistic dentistry: Comparing the approaches and benefits of these two dental care practices

- Traditional Chinese medicine vs Ayurvedic medicine: Analyzing the principles and effectiveness of these ancient healing systems

- Fast food vs home-cooked meals: Assessing the nutritional value and potential health risks associated with each

- Conventional childbirth vs natural childbirth: Exploring the benefits and drawbacks of these two delivery methods for both mother and baby

- Prescription drugs vs over-the-counter drugs: Evaluating the differences in safety, effectiveness, and accessibility of these two types of medications

Health Informative Essay Topics:

- The impact of stress on mental and physical health

- The benefits of regular exercise for overall well-being

- The importance of a balanced diet for maintaining good health

- The dangers of smoking and its effects on the body

- The role of sleep in promoting optimal health and productivity

- The benefits of practicing mindfulness and its impact on mental health

- The effects of excessive screen time on eye health and overall well-being

- The importance of vaccination in preventing the spread of infectious diseases

- The impact of social media on mental health and self-esteem

- The benefits of regular check-ups and preventive healthcare measures

- The dangers of excessive alcohol consumption and its effects on the body

- The role of nutrition in preventing chronic diseases such as diabetes and heart disease

- The impact of air pollution on respiratory health and ways to mitigate its effects

- The benefits of practicing yoga and its positive effects on physical and mental health

- The importance of maintaining a healthy work-life balance for overall well-being

Health Cause and Effect Essay Topics:

- The Impact of Smoking on Lung Cancer Rates

- The Relationship between Poor Diet and Obesity

- The Effects of Stress on Mental Health

- The Connection between Sedentary Lifestyle and Heart Disease

- The Influence of Air Pollution on Respiratory Disorders

- The Link between Alcohol Abuse and Liver Damage

- The Effects of Sleep Deprivation on Cognitive Functioning

- The Relationship between Excessive Sugar Consumption and Diabetes

- The Impact of Fast Food Consumption on Weight Gain

- The Connection between Lack of Physical Activity and Depression

- The Effects of Excessive Screen Time on Eye Health

- The Relationship between Environmental Toxins and Cancer

- The Influence of Genetics on the Development of Chronic Diseases

- The Link between Poor Oral Hygiene and Gum Disease

- The Effects of Excessive Noise Exposure on Hearing Loss

Health Narrative Essay Topics:

- Overcoming a life-threatening illness: My journey to recovery

- The impact of a healthy lifestyle on my overall well-being

- Coping with mental health challenges: My battle with anxiety

- The transformative power of exercise: How I regained my strength

- Navigating the healthcare system: My experience as a patient advocate

- The role of nutrition in managing chronic diseases: My personal story

- Finding hope in the face of a terminal illness: A story of resilience

- The importance of self-care: Learning to prioritize my well-being

- Overcoming addiction: My path to recovery and a healthier life

- The impact of stress on physical health: My journey to finding balance

- The power of alternative medicine: How it changed my perspective on health

- Living with a disability: Embracing a new normal and finding joy

- The role of genetics in health: My family’s journey with hereditary diseases

- The importance of mental health awareness: Breaking the stigma

- The healing power of nature: How spending time outdoors improved my well-being

Health Opinion Essay Topics:

- The effectiveness of alternative medicine in treating chronic illnesses

- The role of government in promoting healthy eating habits

- The benefits and drawbacks of vaccination mandates

- The influence of advertising on unhealthy food choices

- The importance of mental health education in schools

- The impact of technology on physical fitness levels

- The role of pharmaceutical companies in the rising cost of healthcare

- The benefits and risks of using medical marijuana

- The impact of stress on overall health and well-being

- The ethical considerations of organ transplantation

- The impact of air pollution on respiratory health

- The effectiveness of mindfulness and meditation in reducing stress and anxiety

Health Evaluation Essay Topics:

- The impact of social media on mental health

- Evaluating the effectiveness of mindfulness meditation in reducing stress

- Assessing the effectiveness of vaccination programs in preventing infectious diseases

- Evaluating the impact of fast food consumption on obesity rates

- The effectiveness of workplace wellness programs in improving employee health

- Assessing the benefits and risks of alternative medicine practices

- Evaluating the impact of sleep deprivation on cognitive function

- The role of nutrition education in promoting healthy eating habits

- Assessing the effectiveness of smoking cessation programs

- Evaluating the impact of air pollution on respiratory health

- The effectiveness of mental health support services in schools

- Assessing the benefits and risks of genetically modified foods

- Evaluating the impact of alcohol consumption on liver health

- The role of stress management techniques in improving overall well-being

Receive paper in 3 Hours!

- Choose the number of pages.

- Select your deadline.

- Complete your order.

Number of Pages

550 words (double spaced)

Deadline: 10 days left

By clicking "Log In", you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We'll occasionally send you account related and promo emails.

Sign Up for your FREE account

Forget about ChatGPT and get quality content right away.

Narrative Medicine: Every Patient Has a Story

Reflective writing also provides a “safe space” for students to discuss the stresses of medical school and their professional fears, she added.

Jake Measom, a fourth-year medical student at UNR, said that participating in the narrative medicine scholarly concentration has pushed him to be more creative in his approach to patient care. He also sees narrative medicine as a “remedy to burnout,” noting that while the practice of medicine can sometimes feel monotonous, narrative medicine reminds him that “there’s a story to be had everywhere.”

“It not only makes me a better physician in the sense of being able to listen better and be more compassionate,” he said, “it also helps you gain a better understanding of who you are as a person.”

Storytelling as a means of coping

“ First you get your coat. I don’t care if you don’t remember where you left it, you find it. If there was a lot of blood, you ask someone to go quickly to the basement to get you a new set of scrubs. You put on your coat and you go into the bathroom. You look in the mirror and you say it. You use the mother’s name and you use her child’s name. You may not adjust this part in any way.”

That’s an excerpt from “How to Tell a Mother Her Child Is Dead,” which was published last September in the New York Times in the Sunday Review Opinion section. Authored by Naomi Rosenberg, MD, a physician at Temple University Hospital, the piece is a heart-wrenching example of how narrative medicine can serve as an outlet for coping with the harrowing experiences that providers regularly encounter.

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Michael Vitez encouraged Rosenberg to submit the piece in his new role as director of narrative medicine at Temple University Lewis Katz School of Medicine. After retiring from a 30-year career as a reporter at the Philadelphia Inquirer , Vitez approached the school’s dean about using his skills to help students, faculty, and patients translate their experiences into words. The idea morphed into Temple’s new Narrative Medicine Program, which launched in 2016.

Currently, the Temple program is fairly unstructured, with students and faculty working one-on-one with Vitez on their narrative pieces. For example, Vitez said a third-year medical student recently sent him a poem she wrote after an especially difficult day in her psychiatric rotation: “It helped her process her emotions and turn a really bad day into something really valuable,” he noted. Eventually, Temple hopes to offer a certificate and master’s degree in narrative medicine.

“I believe that stories have an incredible power,” said Vitez. “Understanding what a good story is and learning how to interview and ask questions will help you connect with your patients, understand them, and build relationships with them.”

Jay Baruch, MD, associate professor of emergency medicine at Brown’s Warren Alpert Medical School and faculty advisor to the narrative medicine course there, likewise maintains that the type of creative thinking often associated with the arts and humanities—and that narrative medicine often promotes—deserves a more central role in medical education.

“[Students and physicians] need to know the anatomy of a patient’s story just as much as the anatomy of the human body,” he said.

- Health Care

- Medical Schools

- Social Integrity

- Submit Content

- Social Media Account Request

- x (twitter)

- © 2024 The Regents of the University of Michigan

U-M Social Media

- X (Twitter)

My Mental Health Story: A Student Reflects on Her Recovery Journey

In honor of May being Mental Health Awareness Month, I want to share my story in the hope that it resonates with some of you. Hearing other peoples’ stories has been one of the strongest motivators in my recovery journey. Seeing other people be vulnerable has given me bravery to do so as well. So, I share what I have learned not from a place of having all the answers. Quite the opposite, in fact; I don’t really believe there are any concrete answers to confronting a mental health struggle. Each is unique and deserves to be treated that way. However, I do hope that in sharing my personal realizations, it resonates with someone and pushes them just one step closer to living their most authentic life — the life we all deserve to live.

I have struggled with an eating disorder and anxiety for most of my teen and adult life. I was formally diagnosed (otherwise known as the time it became too obvious to hide from my parents and doctor) with anorexia nervosa and generalized anxiety disorder at the beginning of my junior year of high school. Under the careful care of my parents and my treatment team, I was able to keep things ~mostly~ under control. I stayed in school, continued playing sports, and participated in extracurricular activities.

Then, I went away to college. Coming to Michigan, 10 hours away from my home in New York, I was entirely on my own for the first time in my life. And for the first time in my life, I felt free. Or, at least I thought I did. I was ecstatic to be at Michigan. It was my dream school and I was determined to make the best of it, leaving no opportunity unexplored. I threw myself into commitments left and right. Club rowing team, sorority, and a business club, piled on top of the full course load of classes I was taking. And all of that was in addition to merely existing as a freshman — navigating dorm life at Bursley, making friends, finding my place at a huge school.

The thing is, I genuinely thought I was thriving. Getting involved, making great friends, and performing well in my classes is pretty much the best-case scenario for first semester freshman year. I couldn’t see that I was being crushed under an avalanche of essays, exams, club meetings, practices, and parties. Sleep was a luxury and self care was foreign. There was a battle being fought inside my head 24/7, a battle that most of the time I was losing. I was slowly disappearing. Barely held together by the anxiety driving me to chase perfection and an eating disorder to feel a sense of control amidst uncertainty run rampant.

When I returned home for Thanksgiving, the first time since leaving in August, my parents saw through my facade of good grades, involvement, and fun stories. It was obvious I needed help. They wanted me to stay home. But there were only two weeks left of the semester. There was absolutely no way I was going to leave all of my hard work unfinished. I made a deal, if they let me return to Ann Arbor and finish the semester, I would seek treatment when I came home for winter break. They agreed.

When I returned home I completed the intake process at The Renfrew Center for Eating Disorders. Then, I awaited their recommendation.

Residential.

A treatment center 4 hours away from my home, living with about 40 other women also working toward recovery. Days filled with therapy groups, one after another. I would be there for weeks, months even.

A whirlwind of thoughts ran through my head…

I cannot miss school. I’ll fall behind and never be able to catch up.

Your mind is exhausted, you barely finished this semester.

I have leadership positions in my club and my sorority, I can’t just abandon them.

Someone else will have the opportunity to fulfill the position better than you can right now.

I’ll miss precious time with my friends. They will grow closer without me.

You weren’t fully present with them. Your mind was constantly at war with itself.

I am stronger than this. I can do this on my own.

Why are you so determined to be alone? Accept help, you need it desperately.

Other people have it so much worse than I do. Getting help would be selfish.

You getting help does not make anyone else less worthy of getting help.

Perhaps your bravery will encourage someone else to do the same.

Nothing bad has happened to me. I haven’t hit rock bottom.

Why can’t this be your rock bottom?

Is it not enough that you are fighting a battle inside your brain every second of every day?

Is it not enough that your weight has dropped to less than what it was when you were 10 years old?

Is it not enough that you are relentlessly freezing or that your hair is falling out in large clumps?

Is it not enough that you feel exhausted all the time or that you get dizzy when you stand up?

Is it not enough that you are in danger of going into cardiac arrest?

What more are you searching for?

It was the following statement, from my therapist, that finally got through to me:

“Rock bottom is death, do you realize that? The only difference between where you are right now and rock bottom is that you still have a second chance.”

I agreed to go to residential treatment and accept the level of care that I needed, taking off the second semester of my freshman year. I arrived at the Renfrew Center in Philadelphia, bags packed without knowing how long I was staying, feeling terrified and alone. The road ahead of me was dauntingly long but I finally made the decision to put my needs first. Leaving school, no matter how painful right now, would allow me to return as more myself. Without an ongoing battle inside my head, I could be present with my friends, get the most out of my classes, and truly enjoy campus life.

My recovery journey has been anything but smooth. In residential treatment I found support in the community of women fighting for the lives they deserved to live, just as I was. They welcomed me, inspired me, and gave me hope. In therapy I have confronted the most painful beliefs I had about myself, ones that had kept me paralyzed for years. Untangling my authentic self from my eating disorder, rewriting my narrative, learning to feel again. Creating a motivation that was internal. I gained the necessary skills to take recovery into the real world, into a life of true independence and freedom.

Today, almost three years later, I am living my second chance. It is a fight I have vowed to never give up.

The following is a collection of the most important things I have learned throughout my journey…

- I am worthy of being helped. It is okay to ask for help.

Aching for independence, this was not an easy realization. However, the more and more I let my eating disorder take over my thoughts, the less independent I became. Accepting help was the first step in regaining my independence and fighting for myself. At the time I saw it as a moment of weakness. Now, I see it only as a sign of strength. We are all worthy and deserving of help. Ask for it, accept it, let it move you forward.

- I always have time for the things that are important to me.

As high-achieving and driven students, I’m sure many of you can relate to the “not enough time” backtrack constantly playing in your thoughts. It’s not true. Yes, I acknowledge that time is a limited resource. And that we all have commitments. But you are in control of how you decide to spend your time. I’m not saying you can do everything; that is impossible. Rather, I am advocating for intentional decisions about your time. What nourishes you? What makes you feel alive and energized? If something truly matters, make time for it.

- Life isn’t black and white. The depth and richness of life exist in the gray.

I was a perfectionist paralyzed by indecision. No matter how much research and consulting others I did, it was never enough. Yet the one person whose opinion I always seemed to neglect was my own. Why did I so readily trust the opinions of others (or the Internet) and not myself? One thing that helped me begin to rebuild trust with myself was to stop thinking about things as solely black and white, a right choice and a wrong choice. Instead, I had options and information. Information about myself and information about each option. All I could do was make the best choice given the information and options I had at the current moment. There is no way to make a “wrong” choice if you can think about each decision as an opportunity to learn more about yourself.

- I write my own story. And how I narrate it matters.

In untangling and rewriting my internal narrative, I have found that even the smallest shifts can make an incredible difference. I stopped saying things “happened to me.” I am the object of this sentence. A passive being in my own life. Instead, I say, “I lived through this.” I am the subject. I am active and empowered. I have agency.

The way we think shapes our perception. And the way we think is dictated by the words we choose to narrate our lives. We have the power to change our thoughts by changing our narration. Narrate wisely.

Written by #UMSocial intern and Michigan Ross senior Keara Kotten

- Contact | Submit Content

Office of the Vice President for Communications

- Arts & Life

My mental health journey: A personal essay

In Canada, January 30th is Bell Let’s Talk Day, which encourages conversations around mental health. For every text, call, tweet or snap that Canadians make using the #BellLetsTalk hashtag or filter, 5 cents are donated to mental health initiatives that are challenging the stigma around mental health. In light of this event, one of our staff writers shares his experience with mental health in this personal essay.

As I close my eyes and begin to reflect on my mental health journey, the images of tenth grade flip through my mind like snapshots from an invisible reel. When my classmates were enthusiastically answering questions in class, I sulked in my seat. When my classmates were sparking conversations with strangers and befriending them, I felt overwhelmed and crushed being around people I didn’t know. In addition, the heavy workload of the International Baccalaureate program I was in was draining my energy. I struggled every day — in classrooms, during lunch breaks, in the midst of homework assignments — in isolation.

I chose to sit in the very left corner of my classroom where I was least visible to the teacher and most of my classmates. I chose to eat lunch beside my locker, while spending the rest of the break hiding in the restrooms. I chose to pretend that I was sick on quiz and test days. I felt helpless and lost. Books didn’t interest me anymore. My grades dropped. I was stuck in my own prison of thoughts. I was afraid to talk to anyone. I was afraid that people would judge me. I was afraid to fail. I wanted to break away from this prison and free myself. But it was not easy and I gave up. I didn’t know what to do.

It was on one of those dark days that I thought back to something that had once brought me real joy: a sport that I was passionate about in middle school. I could still feel the smile that had spread across my face that day that I had won the junior tournament. But after entering high school, everything that I was passionate about, including this beloved sport, were left to the wayside as I tried to adapt to a new environment. Realizing this, I snapped out of my thoughts, and locked eyes with the badminton racket in the corner of my room. I reached out for the racket, cleaned the dust off of it and I made the decision to join my high school’s badminton club.

When my racket hit the shuttle and a satisfying smashing sound filled the gym, I could feel the euphoric sensation- a rush of endorphins – liberating me from my stress. I felt surprisingly rejuvenated. My muscles were aching but I had a renewed desire to play badminton every day. I did not know how I was going to manage my time but I had to give it a try for a week. I just knew I had to do it.

A few weeks later, I found that I was pushing myself to do better after every strong stroke and every small win. I slowly but surely, regained my confidence, especially after having won a highly anticipated badminton tournament. This was truly a eureka moment for me. It made me think back to a speech Michelle Obama had made, where she stated that “for me, exercise is more than just physical, it’s therapeutic.” Exercise became my therapy. I could focus more on my academics and my grades improved.

My own mental health struggle made me wonder if we were over-diagnosing and over-treating mental health disorders or if lifestyle changes alone could boost mental health. This led me to research the benefits of physical activity in managing mild-to-moderate mental health concerns, especially depression and anxiety. The more I learned, the more I wanted to share this information with others. So much so that I metamorphosed into a mental health advocate.

I also decided to take an even more proactive role in the matter by founding a student-led provincial organization the Active Mental Health Initiative (AMHI), with the goal of raising awareness of the benefits of physical activity on mental health. Bringing students from across the province of Ontario, Canada together, AMHI organizes symposiums and workshops to address the increasing rates of mental health problems that students currently face. With AMHI, we want to change the misconception that mental health is separate from physical health. In reality, both mental and physical health are deeply intertwined. Kate Middleton rightly said, ”A child’s mental health is just as important as their physical health and deserves the same quality of support.”

Seeing that January 30 is #BellLetsTalk day, I find myself thinking back to my own mental health experiences and those of other students quite often. It’s my hope that through the work we do with AMHI, everyone will have the opportunity to feel well, find time for self-care, sense the strong waves, develop and use their coping skills to surf the high tides and seek timely help. Please visit our website and our Facebook page for more information. Anyone interested in this initiative can start AMHI clubs in their high schools and facilitate “Healthy Mind Healthy Body” workshops at middle schools. Join us in these ongoing projects and advocate for the cause of mental health.

Ishaan Sachdeva

Please note that opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views and values of The Blank Page.

Related Posts

Why I started my politically-charged YouTube series

Special feature: a glimpse into the lovely mind, the positive impact yoga has on mental health, feature: on mental illness in medical school.

Depression: One of the greatest threats of our time

Is ‘spiritual health’ a thing, the many reasons why.

Can music help us sleep?

What we fail to understand about mental illness, stressed out start colouring..

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write a narrative essay | Example & tips

How to Write a Narrative Essay | Example & Tips

Published on July 24, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

A narrative essay tells a story. In most cases, this is a story about a personal experience you had. This type of essay , along with the descriptive essay , allows you to get personal and creative, unlike most academic writing .

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is a narrative essay for, choosing a topic, interactive example of a narrative essay, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about narrative essays.

When assigned a narrative essay, you might find yourself wondering: Why does my teacher want to hear this story? Topics for narrative essays can range from the important to the trivial. Usually the point is not so much the story itself, but the way you tell it.

A narrative essay is a way of testing your ability to tell a story in a clear and interesting way. You’re expected to think about where your story begins and ends, and how to convey it with eye-catching language and a satisfying pace.

These skills are quite different from those needed for formal academic writing. For instance, in a narrative essay the use of the first person (“I”) is encouraged, as is the use of figurative language, dialogue, and suspense.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Narrative essay assignments vary widely in the amount of direction you’re given about your topic. You may be assigned quite a specific topic or choice of topics to work with.

- Write a story about your first day of school.

- Write a story about your favorite holiday destination.

You may also be given prompts that leave you a much wider choice of topic.

- Write about an experience where you learned something about yourself.

- Write about an achievement you are proud of. What did you accomplish, and how?

In these cases, you might have to think harder to decide what story you want to tell. The best kind of story for a narrative essay is one you can use to talk about a particular theme or lesson, or that takes a surprising turn somewhere along the way.

For example, a trip where everything went according to plan makes for a less interesting story than one where something unexpected happened that you then had to respond to. Choose an experience that might surprise the reader or teach them something.

Narrative essays in college applications

When applying for college , you might be asked to write a narrative essay that expresses something about your personal qualities.

For example, this application prompt from Common App requires you to respond with a narrative essay.

In this context, choose a story that is not only interesting but also expresses the qualities the prompt is looking for—here, resilience and the ability to learn from failure—and frame the story in a way that emphasizes these qualities.

An example of a short narrative essay, responding to the prompt “Write about an experience where you learned something about yourself,” is shown below.

Hover over different parts of the text to see how the structure works.

Since elementary school, I have always favored subjects like science and math over the humanities. My instinct was always to think of these subjects as more solid and serious than classes like English. If there was no right answer, I thought, why bother? But recently I had an experience that taught me my academic interests are more flexible than I had thought: I took my first philosophy class.

Before I entered the classroom, I was skeptical. I waited outside with the other students and wondered what exactly philosophy would involve—I really had no idea. I imagined something pretty abstract: long, stilted conversations pondering the meaning of life. But what I got was something quite different.

A young man in jeans, Mr. Jones—“but you can call me Rob”—was far from the white-haired, buttoned-up old man I had half-expected. And rather than pulling us into pedantic arguments about obscure philosophical points, Rob engaged us on our level. To talk free will, we looked at our own choices. To talk ethics, we looked at dilemmas we had faced ourselves. By the end of class, I’d discovered that questions with no right answer can turn out to be the most interesting ones.

The experience has taught me to look at things a little more “philosophically”—and not just because it was a philosophy class! I learned that if I let go of my preconceptions, I can actually get a lot out of subjects I was previously dismissive of. The class taught me—in more ways than one—to look at things with an open mind.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

If you’re not given much guidance on what your narrative essay should be about, consider the context and scope of the assignment. What kind of story is relevant, interesting, and possible to tell within the word count?

The best kind of story for a narrative essay is one you can use to reflect on a particular theme or lesson, or that takes a surprising turn somewhere along the way.

Don’t worry too much if your topic seems unoriginal. The point of a narrative essay is how you tell the story and the point you make with it, not the subject of the story itself.

Narrative essays are usually assigned as writing exercises at high school or in university composition classes. They may also form part of a university application.

When you are prompted to tell a story about your own life or experiences, a narrative essay is usually the right response.

The key difference is that a narrative essay is designed to tell a complete story, while a descriptive essay is meant to convey an intense description of a particular place, object, or concept.

Narrative and descriptive essays both allow you to write more personally and creatively than other kinds of essays , and similar writing skills can apply to both.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, July 23). How to Write a Narrative Essay | Example & Tips. Scribbr. Retrieved March 31, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/narrative-essay/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write an expository essay, how to write a descriptive essay | example & tips, how to write your personal statement | strategies & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Narrative Health: Using Story to Explore Definitions of Health and Address Bias in Health Care

Affiliation.

- 1 Community University Health Care Center, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

- PMID: 30939266

- PMCID: PMC6380479

- DOI: 10.7812/TPP/18-052

When defining health and illness, we often look to governing bodies such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization rather than our communities. With health disparities prominent throughout the US, it is important to look at the structures we have set forth in health care and find new ways to address health as well as new definitions. Storytelling is a valuable tool to help understand how our communities address health and the place of the hospital or clinic in their health. Narrative Health focuses not just on storytelling but also story listening. At the Community-University Health Care Center in Minneapolis, MN, we have implemented narrative health programs with patients and learners from various health professions. Using creative writing pedagogy and techniques to decentralize the practitioner-patient binary of illness, we learn about our patients' stories of health and experiences with health care. It is important to move past the definitions of health to the complexities of story that allow for the human aspects of illness to be absorbed and understood.

- Communication*

- Healthcare Disparities*

- Social Determinants of Health*

16 Personal Essays About Mental Health Worth Reading

Here are some of the most moving and illuminating essays published on BuzzFeed about mental illness, wellness, and the way our minds work.

BuzzFeed Staff

1. My Best Friend Saved Me When I Attempted Suicide, But I Didn’t Save Her — Drusilla Moorhouse

"I was serious about killing myself. My best friend wasn’t — but she’s the one who’s dead."

2. Life Is What Happens While You’re Googling Symptoms Of Cancer — Ramona Emerson

"After a lifetime of hypochondria, I was finally diagnosed with my very own medical condition. And maybe, in a weird way, it’s made me less afraid to die."

3. How I Learned To Be OK With Feeling Sad — Mac McClelland

"It wasn’t easy, or cheap."

4. Who Gets To Be The “Good Schizophrenic”? — Esmé Weijun Wang

"When you’re labeled as crazy, the “right” kind of diagnosis could mean the difference between a productive life and a life sentence."

5. Why Do I Miss Being Bipolar? — Sasha Chapin

"The medication I take to treat my bipolar disorder works perfectly. Sometimes I wish it didn’t."

6. What My Best Friend And I Didn’t Learn About Loss — Zan Romanoff

"When my closest friend’s first baby was stillborn, we navigated through depression and grief together."

7. I Can’t Live Without Fear, But I Can Learn To Be OK With It — Arianna Rebolini

"I’ve become obsessively afraid that the people I love will die. Now I have to teach myself how to be OK with that."

8. What It’s Like Having PPD As A Black Woman — Tyrese Coleman

"It took me two years to even acknowledge I’d been depressed after the birth of my twin sons. I wonder how much it had to do with the way I had been taught to be strong."

9. Notes On An Eating Disorder — Larissa Pham

"I still tell my friends I am in recovery so they will hold me accountable."

10. What Comedy Taught Me About My Mental Illness — Kate Lindstedt

"I didn’t expect it, but stand-up comedy has given me the freedom to talk about depression and anxiety on my own terms."

11. The Night I Spoke Up About My #BlackSuicide — Terrell J. Starr

"My entire life was shaped by violence, so I wanted to end it violently. But I didn’t — thanks to overcoming the stigma surrounding African-Americans and depression, and to building a community on Twitter."

12. Knitting Myself Back Together — Alanna Okun

"The best way I’ve found to fight my anxiety is with a pair of knitting needles."

13. I Started Therapy So I Could Take Better Care Of Myself — Matt Ortile

"I’d known for a while that I needed to see a therapist. It wasn’t until I felt like I could do without help that I finally sought it."

14. I’m Mending My Broken Relationship With Food — Anita Badejo

"After a lifetime struggling with disordered eating, I’m still figuring out how to have a healthy relationship with my body and what I feed it."

15. I Found Love In A Hopeless Mess — Kate Conger

"Dehoarding my partner’s childhood home gave me a way to understand his mother, but I’m still not sure how to live with the habit he’s inherited."

16. When Taking Anxiety Medication Is A Revolutionary Act — Tracy Clayton

"I had to learn how to love myself enough to take care of myself. It wasn’t easy."