- Nieman Foundation

- Fellowships

To promote and elevate the standards of journalism

Nieman News

Back to News

Strictly Q&A

February 24, 2023, auschwitz stories told by those who lived them, the director of the auschwitz-birkenau state museum in poland has collected hundreds of survivor testimonials, told with a rawness that no outsider could.

By Andrea Pitzer

Tagged with

The gate into the Auschwitz concentration camp in WWII Nazi-occupied Poland. Translated, the words say "Work sets you free." Frederick Wallace via Unsplash

Piotr Cywiński

“ Auschwitz: A Monograph on the Human ,” a 2022 book by Piotr Cywiński, tries to address that abyss. He does so not by working his way along the boundaries around Auschwitz — the dates and architecture of genocide that swallowed more than a million people , the overwhelming majority of them Jewish — but instead dives into the emptiness itself, gathering details from hundreds of memoirs and official testimonies, along with trial minutes and questionnaires. Chronology doesn’t serve as the organizing principle; instead, the book is divided into themes of human emotion and experience, such as “Decency,” “Hierarchy,” and “Fear” that emerged from looking at the survivors’ accounts as a whole.

Cywiński is a historian and has been the director of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum in Poland for more than 16 years. His polyphonic approach of bringing in hundreds of voices to tell one overarching story struck me as an answer to the question of how to write about something as vast as incomprehensible as Auschwitz.

This focus made me think of Pulitzer winner Katherine Boo who, in talking about her book “Behind the Beautiful Forevers,” balked at the idea of the journalistic impulse to make an individual a symbol of a place or an event. In a 2012 interview Poynter.org, she warned of the dangers of using one person’s story to represent a bigger concept:

“Nobody is representative. That’s just narrative nonsense. People may be part of a larger story or structure or institution, but they’re still people. Making them representative loses sight of that.”

Cywiński’s Auschwitz monograph illustrates this idea elegantly, gathering related observations with care then ceding nearly all his book to camp prisoners themselves, letting their archival testimonies converse with one another, with minimal interpretation and explanation.

Last December, more than 80 years after Nazis first sent prisoners to the small town of Oświęcim in Poland, Cywiński sat for a public interview with me at the Kosciuszko Foundation in New York. We spoke about why some stories went untold for decades, why understanding life at Auschwitz remains almost impossible and why it’s important to include a multitude of perspectives to even begin to glimpse the real story of Auschwitz.

Here are some excerpts from our conversation, which have been condensed and edited for clarity:

Train tracks that lead from the entry to the Birkenau concentration camp to the gas chambers. Birkenauwas an extension of the Auschwitz camp in WWII Nazi-occupied Poland. Andrea Pitzer

Y ou mention several times in the book the experience of prisoners entering a different world on arrival at Auschwitz. This is extremely important, and I think that this was maybe the main reason why so many survivors started to speak about Auschwitz so late. And still, 95 percent of survivors didn’t speak, didn’t give testimonials, didn’t write any memoirs. I think that they were afraid that using words from our normal world would never give the sense of the reality of the camp.

When I’m hungry, it doesn’t mean the same as when you are hungry in the camp. It’s completely different, and it’s like this with many other emotions, because they are at an extreme that we can’t imagine in our world. You’re put in a situation when the most important factors, like space and time, are completely different. You don’t know how long you will survive. When you’re speaking about hope, it means some plans for the future, but in the camp it means to survive for the next five or ten minutes. And at every moment, somebody is dying around you. That means you will also die, perhaps in a few minutes or in one hour. It’s a completely different kind of time than we experience in normal life.

At the beginning, I was thinking that I would speak about death at the end of the book. This was an error. In Auschwitz death did not happen at the end; it was present at all times and everywhere.

One of the essays in the collection is on death. There’s a quote from a survivor: “not only is life and human dignity violated here but human death counts for nothing.” For us, death is so tragic. It’s a big mystery. We will arrive all of us at one moment to face our death, but it’s something that we consider with a religious or para-religious approach, with a philosophical approach, even if we if we don’t want to organize our lives according to this destination.

In the camp death was everywhere and could arrive at every moment. Maybe the only thing that they were sure of was death. It’s also completely different when it’s an inverse point to our way of thinking about death. If I ask what you’re sure about in the immediate future, you would tell me about how you will go back home and get dinner or do something with your family. But nobody would be thinking about death as something that we can be sure of happening in the present moment.

One quote from another testimony says: “Among the Auschwitz prisoners who wrote their memoirs none of them claims the camp ennobled people.” Yet it’s woven into a lot of fabric of society before and after Auschwitz that suffering brings a kind of nobility, that there is something inherent in suffering that makes us pure or better. I think it’s important that is not what’s reflected in most of these testimonies. Yes, this perspective is present in very few testimonies. What we consider as a moral system in our society was completely different when it was recreated inside the camp. I think it was also a factor in the incapacity to speak about Auschwitz for many survivors because they begin to justify themselves, and they don’t want to justify themselves. They knew that their choices inside the camp — daily choices, I do not speak about dramatic choices — the daily choices were how to survive, to have one or two or three or days more to stay alive.

The position where you stand at the queue in order to have your soup: If you go at the starting point of the distribution of the soup, you will receive only water; if you go at the end, you’ll be beaten by some very well-positioned prisoners, some kapo or some people from the blocks, because they know that at the end, there will be some potatoes. So you have to find your own position, not too quickly and not too late. But that means you will take this place from some other prisoner. And with every choice you made, that means somebody else did not get this choice.

You also address the Sonderkommando — these people who were drafted into being active participants in the murder of other prisoners at Auschwitz. It’s perhaps the most tragic history in the camp, the story of the Sonderkommando . They were in general young men taken from different transports and put to work around the gas chambers and the crematoria. They had to burn corpses, to make all this machinery function. A clear majority were Jews, and many of them were coming from Jewish Orthodox families, and cremation of course was something they couldn’t have imagined. For decades after the war, they were considered maybe not as perpetrators but as collaborators of perpetrators, except two or three, like Shlomo Venezia or Filip Müller . Many of them stayed silent for years.

We are all very proud of our culture, our education and our sense of values. We feel really prepared to confront difficulties. Those people also, certainly they were thinking like this. But a few days were enough to change a person arriving from a normal world to a person completely acting according to the camp rules, thinking in a different way, approaching other humans in a different way, considering himself as a completely different person.

Another example of a theme that we in our world might think of quite differently than the voices we hear in the book is this idea of sacrifice. I want to speak specifically about Father Kolbe , because many people have heard about this story, and he was canonized later for switching places with a condemned person. Here’s what one of the survivors said about him: “I must stress that what impressed us was not that he gave up his life for someone else, for life wasn’t worth much in the camp. We were impressed that in front of so many SS men and prisoner functionaries, he had broken discipline and dared to step out of rank.” It’s quite different than what we might think. I heard many words like this. “If you give your life for another, that does not mean you give your life. You give your last few days or a few weeks, it’s not something exceptional. But breaking the rules, it is something, yes.”

And there were, of course, different levels of sacrifice. You can share, for example, your bread. So you have some bread. Your kid or your friend for some reason has no more bread, and maybe he’s in deeper need. You can give him the half of your bread; it seems nothing. But what was the remark of the prisoners? “Oh, look at him he’s starting to share his bread. He has no will to survive. He will be finished very quickly.” It’s not like a sacrifice, it’s like suicide. This is why I am speaking about an entire axiology that is completely different in the camp than in our perception.

A prisoners' room at the Auschwitz concentration camp. Auschwitz memorial, Poland.

You note that some of those people wo were most deeply tied into their communities actually were a tremendous disadvantage in the camp. Those who had the easiest time adapting to the camp were people coming from very low socioeconomic levels from big cities, people who had very hard childhoods with many problems in their lives. They’ve got ideas on how to adapt to those difficulties.

But at the opposite end, you get for example people from the countryside, normal people without any education, unable to understand or to speak German, unable to imagine a different world than their own, living all the time in cyclical time according to the seasons. They found themselves in the camp and were completely unable to adapt. In general they did not leave testimonies after the war, because if you finish two grades in the schools or even not two, you are unable to write your testimony.

But many other prisoners themselves tried to enter in contact with them and describe them, and this was something incredible. Many times you think it’s those people coming from very traditional settings with centuries of culture and systems of ethics who will be the strongest in a difficult time. Not really. Not really.

One of the things the general public forgets today about the enormity of the death camps and the Holocaust was that it took many years to frame even the basic understanding that we have today of what happened. It was not understood in the immediate postwar time, so survivors didn’t have that space to speak, because what they experienced was in some ways quite different than what was first said about what had happened in the camps. The situation of somebody captured in 1940 in Warsaw because he prepared some anti-Nazi, anti-German action, as a scout or something like this, was completely different than somebody who was taken from their house for nothing. The latter was unable to know why he was in this camp. It was difficult to create a definite narrative after the war if you were taken for no reason from your house or from the street and sent to the camp. If somebody was involved in some unusual actions, it was different. He was able afterward to say, “Yes I suffered a lot. It was inhuman, but I was fighting against something.”

This psychological difference was huge in the postwar narratives.

A question from the audience, from a woman whose father spent years in Auschwitz, asks about the difference between the reception of Christian and Jewish narratives. In Poland, especially after 1968, the camp narrative was more organized by Christian prisoners. In the Western world it was more organized by Jewish survivors. It was a very clear difference between the two narratives.

I remember in the ’90s when Communism ended, it became possible to travel to Poland to visit Auschwitz. The two communities of remembrance met in the same place and did not recognize each other. It was like they were speaking about some completely different history. There were different symbols, words, approaches. It created tensions, it created emotions.

It took time, even a whole generation — up until 2010 or later — for those different worlds not only to accept each other but to understand that, yes, they’re all attached to the same story, to the same place. It was very, very difficult.

And at the same time, in the late ’90s, some new history arrived. The genocide of the Roma and Sinti — so-called gypsies — was discovered by the larger public. Then Russia started to speak about the Soviet prisoners of war who were put in Auschwitz.

I think we are headed in a good direction. We are learning to understand each other and all these stories.

Andrea Pitzer is the author of three books of narrative nonfiction that explore untold histories. She was the editor of Nieman Storyboard from 2009-2012.

Teaching the Holocaust through literature: four books to help young people gain deeper understanding

Reader in Literature, University of Portsmouth

Disclosure statement

Christine Berberich does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Portsmouth provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

A survey commissioned in 2019 revealed the shocking result that over half of Britons did not know that at least six millions Jews had been murdered during the Holocaust.

This result was all the more surprising given the fact that the Holocaust, as a topic, has been part of the national curriculum in England and Wales since its creation in 1991 . The 2014 iteration of the national curriculum has the Holocaust as a firm part of key stage 3 history – compulsory for all 11 to 14-year-olds in state schools. Additionally, many secondary school pupils may encounter the Holocaust as a topic in English or religious education lessons.

However, research into what school pupils in England know about the Holocaust shows that they lack knowledge about its context . They may know bare facts – ghettos, deportations, concentration camps – but are less clear on the ideology that led to the rise of the Nazis and the Holocaust in the first place. Pupils may not be clear what exactly it is they need to take away from those lessons and how they can be relevant to their contemporary lives.

For instance, it is important to understand how politicians sought to gain popular support by blaming minorities such as Jewish people for all the ills Germany experienced after the first world war. Relentless anti-Jewish propaganda was used to indoctrinate the general population.

It is for this reason that literature can be a meaningful additional teaching tool, not only in schools but also for everybody interested in the events leading up to the Holocaust. Literature can broaden horizons and deepen knowledge. It can offer different perspectives, often in the same narrative; it teaches us empathy but it can also help us to acquire facts and additional knowledge.

However, the sheer number of books on the Holocaust – survivor accounts, biographies, novels, factual books – can be overwhelming.

Sometimes, bestselling books on the Holocaust, such as John Boyne’s The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas (2006) or Heather Morris’ The Tattooist of Auschwitz (2018), lack the factually correct underpinning that is necessary to make them a good way to learn about the history. It is consequently vital to find books that meaningfully introduce their readers to the topic and that provide carefully researched historical context.

When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit

One example is Judith Kerr’s When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit (1971) which is based on Kerr’s own childhood experience. It is the story of 9-year-old Jewish girl Anna who has a happy childhood in Germany until the day her father, wanted by the Nazis, has to leave the country.

Anna’s subsequent narrative outlines the repressions affecting Jewish life on a daily basis. She encounters public events such as the staged book burnings and the daily propaganda that perpetuated falsehoods about Jews. As such, it is an excellent – though hard-hitting – way to introduce a younger readership to the prejudices and reprisals Jews were increasingly subjected to in Nazi Germany.

The Diary of a Young Girl

Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl (1947) is probably the one Holocaust book most people have heard of. It charts the two years Anne and her family spent in hiding in Amsterdam.

The book is often praised for its positive and hopeful message. It is, however, vital that even young readers are made aware of the fact that the Franks were eventually discovered by the Nazis, deported to Auschwitz and from there to Bergen-Belsen, where Anne tragically died in early 1945.

Survivor accounts are generally the best way to learn about the Holocaust. Older teenagers could read Elie Wiesel’s outstanding Night (1958). It describes, in a dispassionate voice, Wiesel’s experiences of being deported from his home town of Sighet in what is now Romania, first to Auschwitz and from there to Buchenwald.

Wiesel lost his father, mother and youngest sister in the Holocaust and dedicated his life to Holocaust education. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace in 1986. If anybody plans to read just one book on the Holocaust, it should probably be this one.

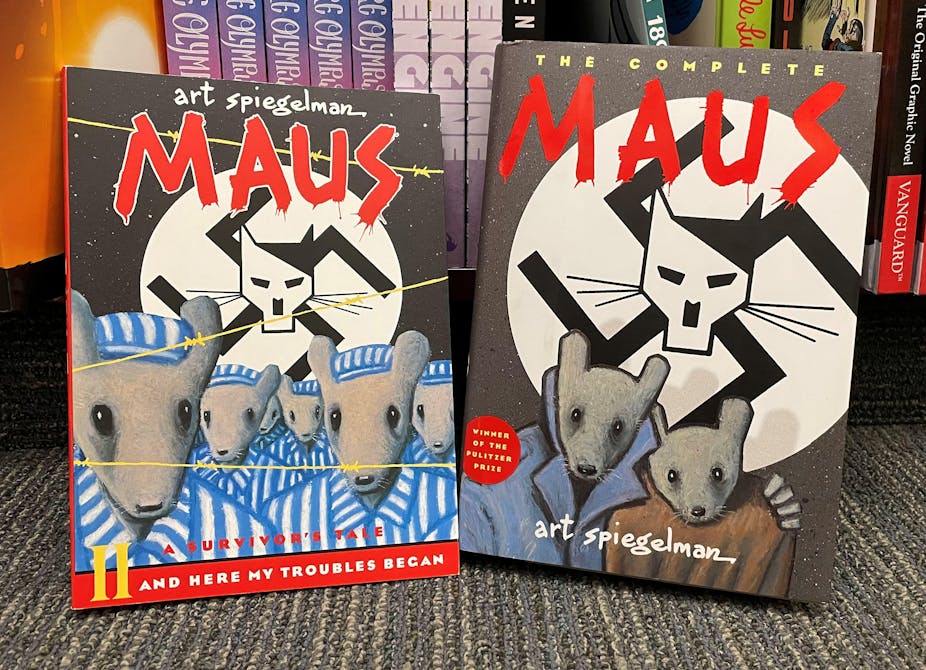

Some young readers might be reluctant to read such hard-hitting accounts by witnesses and survivors of the Holocaust. They might be persuaded to engage with the topic, though, through Art Spiegelman’s seminal graphic novel Maus .

Spiegelman’s book recounts the story of his father Vladek and mother Anja, who both survived Nazi concentration camps. He uses the imagery of an animal fable by depicting his Jewish characters as mice who are chased by the Nazi cats. While this is potentially a distancing device to soften the impact of his illustrations, it also helps Spiegelman to pass critical comments on the Nazis’ notorious attempts to classify people into strictly segregated groups.

Maus made it back into the bestseller lists in January 2022 when a County School Board in Tennessee controversially banned it from its classrooms and libraries. Censorship is not yet a thing of the past – and it is, maybe, especially the people making decisions about education who ought to read these texts.

Using literature as a tool to augment Holocaust teaching in secondary schools might be a good way to further pupils’ learning and understanding not just of the Holocaust, but of the ideologies, populism and propaganda that lay behind it – and how to identify similar narratives that are, worryingly, on the rise again in the world around them.

- Antisemitism

- International Holocaust Remembrance Day

- Holocaust Memorial Day

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

Data and Reporting Analyst

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Holocaust Literature

Introduction, early criticism.

- History and Criticism

- Ethics and Morality

- Memory, Remembrance, and Testimony

- Popular Culture and the Holocaust Novel

- Literature in Hebrew and German

- Gender and Jewish Identity

- Children, Youth, and Generations

- Study and Teaching

- Anthologies and Reference Guides

- Online Resources

- Suggested Primary Texts

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Abraham Sutzkever

- History of the Holocaust

- Holocaust Museums and Memorials

- Philosophical and Theological Responses to the Holocaust

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Legal Circumventions in Rabbinic Law

- Yiddish Women's Fiction

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Holocaust Literature by Lia Deromedi LAST REVIEWED: 18 August 2021 LAST MODIFIED: 23 August 2017 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199840731-0158

There are seemingly infinite anxieties about the historical, literary, ethical, and theological responsibilities of Holocaust representation. Early critics recognized the ethical dangers inherent in writing about an extreme historical event. But they also saw the expansion of possibility so that an evolving body of literature transcends national and cultural boundaries and shares a spectrum of attitudes toward the concentration camps and the world beyond. While later critics have focused on new issues, such as the resurgence and proliferation of Holocaust literature for popular consumption, and how distance in time alters representation, these works asked the first hard questions and revealed the innovative ways writers approach the historical event. Holocaust literature challenges the idea that there are distinct unsurpassable borders separating history from artistic representation. Criticism often calls attention to this idea of boundaries between history and art, all of which Holocaust literature seems to obscure or transgress in some way, revealing that the line between complete invention and genre distortion has already been crossed. Similarly, the ability to suggest experiences that could have happened or did happen, rather than documented cases, gives the Holocaust writer the opportunity to rethink and reevaluate actual events and emotions in a space that is freed from presumed boundaries that restrict the narration to strict truth or reality. Holocaust literature has been variously argued as generically different from postmodern postwar texts and as integrated within them. But more important than concerns about genre is the argument that much of the power in literature appears to originate from the dual claims it makes on fiction and fact to engage readers. Within critical and literary writing, the Holocaust is a vastly represented 20th-century event. Literary responses to history include fiction and autobiography written by survivors with compulsions to communicate the Holocaust, as well as writers with no direct experience who also share this compulsion. The 21st-century scholar of Holocaust literature will recognize its specificity and its relevance within the context of history and contemporary public consciousness, along with its important contribution to the ongoing history of literary scholarship.

Langer 1975 , and Langer 1978 , and Rosenfeld 1980 embody some of the pioneering scholarship in the field of Holocaust literature. This section focuses on some of the criticism from the 1970s and 1980s that first addressed the importance of this literary genre, the emergence of which began immediately after the event, but only gained popularity and momentum several decades later. These works helped establish Holocaust literature as an arguably distinct and significant genre in the postmodern, postwar field. This early criticism often draws on survivor testimonies and memoirs, as well as lesser-known creative works, to explore what became a phenomenon in Holocaust representation. Works such as Ezrahi 1980 examine the ways in which writers who embraced the subject were forced to extend the limits of imagination to encompass such a real horror. As seen in Rosenfeld 1980 , these critics were among the first to demand that “Holocaust literature” be examined in different ways than other literature, to be treated as part of the postmodern period but also a post-Holocaust period; what has been called a unique event in history demands a critical examination of its representation that is also distinctive. Although Young 1988 may also be included in later eras of criticism, this early work reinforces the key points made by the others that interpretation of Holocaust literature remains paramount for remembering the event. It is important to be aware of the first important criticism on the subject when reading contemporary analyses.

Ezrahi, Sidra DeKoven. By Words Alone: The Holocaust in Literature . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980.

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226233376.001.0001

Discussion of the fine line that Holocaust literature straddles between real events and imagined art. Ezrahi stretches the boundaries of the subject to discuss documentation, testimony, survivor literature, the particularly Jewish aspect of the Holocaust in the form of lamentations and covenantal context, the mythologization of the event, and American Holocaust literature.

Langer, Lawrence L. The Holocaust and the Literary Imagination . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1975.

Langer addresses the challenge that literature and the imagination have in making the Holocaust accessible to readers. A discussion of writers, some of them survivors, exploring the paradox of how literature can affect readers who can no longer be shocked by a most shocking atrocity.

Langer, Lawrence L. The Age of Atrocity: Death in Modern Literature . Boston: Beacon, 1978.

Langer further investigates how the tragedy of mass death affects insight and meaning. He offers an overview using Jean Amery and Ernest Becker, with their respective theories of torture as transcendence and “creatureliness,” examining works of the Holocaust and other atrocities.

Rosenfeld, Alvin H. A Double Dying: Reflections on Holocaust Literature . Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1980.

Argues for the special status of Holocaust literature to understand the enormity of the event and its repercussions for humanity. The title of the book suggests Rosenfeld’s main point that the Holocaust killed not only men, but also the “idea of man.”

Young, James E. Writing and Rewriting the Holocaust: Narrative and the Consequences of Interpretation . Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988.

Historiographical work that interprets the meaning of Holocaust literature. Examines the perpetuation of Holocaust memory and understanding in several forms of media. Includes an extensive bibliography of works.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Jewish Studies »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Abraham Isaac Kook

- Agudat Yisrael

- Ahad Ha' am

- American Hebrew Literature

- American Jewish Artists

- American Jewish Literature

- American Jewish Sociology

- Ancient Anti-Semitism

- An-sky (Shloyme Zanvil Rapoport)

- Anthropology of the Jews

- Anti-Semitism, Modern

- Apocalypticism and Messianism

- Archaeology, Second Temple

- Archaeology: The Rabbinic Period

- Art, Synagogue

- Austria, The Holocaust In

- Austro-Hungarian Empire, 1867-1918

- Baron, Devorah

- Biblical Archaeology

- Biblical Literature

- Bratslav/Breslev Hasidism

- Buber, Martin

- Bukharan Jews

- Central Asia, Jews in

- Chagall, Marc

- Classical Islam, Jews Under

- Cohen, Hermann

- Culture, Israeli

- David Ben-Gurion

- David Bergelson

- Dead Sea Scrolls

- Death, Burial, and the Afterlife

- Debbie Friedman

- Deuteronomy

- Dietary Laws

- Dubnov, Simon

- Dutch Republic: 17th-18th Centuries

- Early Modern Period, Christian Yiddishism in the

- Eastern European Haskalah

- Economic Justice in the Talmud

- Edith Stein

- Emancipation

- Emmanuel Levinas

- Environment, Judaism and the

- Ethics, Jewish

- Ethiopian Jews

- Exiting Orthodox Judaism

- Folktales, Jewish

- Forverts/Forward

- Frank, Jacob

- Gender and Modern Jewish Thought

- Germany, Early Modern

- Ghettos in the Holocaust

- Goldman, Emma

- Graetz, Heinrich

- Hasidism, Lubavitch

- Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment) Literature

- Hebrew Bible, Blood in the

- Hebrew Bible, Memory and History in the

- Hebrew Literature and Music

- Hebrew Literature Outside of Israel Since 1948

- History, Early Modern Jewish

- Holocaust in France, The

- Holocaust in Germany, The

- Holocaust in Poland, The

- Holocaust in the Netherlands, The

- Holocaust in the Soviet Union, The

- (Holocaust) Memorial Books

- Holocaust, Philosophical and Theological Responses to the

- Holocaust Survivors, Children of

- Humor, Jewish

- Ibn Ezra, Abraham

- Indian Jews

- Isaac Bashevis Singer

- Israel Ba'al Shem Tov

- Israel, Crime and Policing in

- Israel, Religion and State in

- Israeli Economy

- Israeli Film

- Israeli Literature

- Israel's Society

- Italian Jewish Enlightenment

- Italian Jewish Literature (Ninth to Nineteenth Century)

- Jewish American Children's Literature

- Jewish American Women Writers in the 18th and 19th Centuri...

- Jewish Bible Translations

- Jewish Culture, Children and Childhood in

- Jewish Diaspora

- Jewish Economic History

- Jewish Folklore, Chełm in

- Jewish Genetics

- Jewish Heritage and Cultural Revival in Poland

- Jewish Morocco

- Jewish Names

- Jewish Studies, Dance in

- Jewish Territorialism (in Relation to Jewish Studies)

- Jewish-Christian Polemics Until the 15th Century

- Jews and Animals

- Joseph Ber Soloveitchik

- Josephus, Flavius

- Judaism and Buddhism

- Kalonymus Kalman Shapira

- Khmelnytsky/Chmielnitzki

- Kibbutz, The

- Kiryas Joel and Satmar

- Languages, Jewish

- Late Antique (Roman and Byzantine) History

- Latin American Jewish Studies

- Law, Biblical

- Law in the Rabbinic Period

- Life Cycle Rituals

- Literature Before 1800, Yiddish

- Literature, Hellenistic Jewish

- Literature, Holocaust

- Literature, Latin American Jewish

- Literature, Medieval

- Literature, Modern Hebrew

- Literature, Rabbinic

- Magic, Ancient Jewish

- Maimonides, Moses

- Maurice Schwartz

- Medieval and Renaissance Political Thought

- Medieval Anti-Judaism

- Medieval Islam, Jews under

- Meir, Golda

- Menachem Begin

- Mendelssohn, Moses

- Messianic Thought and Movements

- Middle Ages, the Hebrew Story in the

- Minority Literatures in Israel

- Modern Germany

- Modern Hebrew Poetry

- Modern Jewish History

- Modern Kabbalah

- Moses Maimonides: Mishneh Torah

- Music, East European Jewish Folk

- Music, Jews and

- Nathan Birnbaum

- Nazi Germany, Kristallnacht: The November Pogrom 1938 in

- Neo-Hasidism

- New Age Judaism

- New York City

- North Africa

- Orthodoxy, Post-World War II

- Palestine/Israel, Yiddish in

- Palestinian Talmud/Yerushalmi

- Philo of Alexandria

- Poetry in Spain, Hebrew

- Poland, 1800-1939

- Poland, Hasidism in

- Poland Until The Late 18th Century

- Politics and Political Leaders, Israeli

- Politics, Modern Jewish

- Prayer and Liturgy

- Purity and Impurity in Ancient Israel and Early Judaism

- Queer Jewish Texts in the Americas

- Rabbi Yeheil Michel Epstein and his Arukh Hashulchan

- Rabbinic Exegesis (Midrash) and Literary Theory

- Race and American Judaism

- Rashi's Commentary on the Bible

- Reform Judaism

- Ritual Objects and Folk Art

- Rosenzweig, Franz

- Russian Jewish Culture

- Sabbatianism

- Sacrifice in the Bible

- Sarah Schenirer and Bais Yaakov

- Scholem, Gershom

- Second Temple Period, The

- Sephardi Jews

- Sexuality and the Body

- Shlomo Carlebach

- Shmuel Yosef Agnon

- Shulhan Arukh and Sixteenth Century Jewish Law, The

- Sociology, European Jewish

- South African Jewry

- Soviet Union, Jews in the

- Soviet Yiddish Literature

- Space in Modern Hebrew Literature

- Spinoza, Baruch

- Sutzkever, Abraham

- Talmud and Philosophy

- Talmud, Narrative in the

- The Druze Community in Israel

- The Early Modern Yiddish Bible, 1534–1686

- The General Jewish Workers’ Bund

- The Modern Jewish Bible, Facets of

- Theater, Israeli

- Theme, Exodus as a

- Tractate Avodah Zarah (in the Talmud)

- Translation

- Translation in Hebrew Literature, Traditions of

- United States

- Walter Benjamin

- Weinreich, Max

- Wissenschaft des Judentums

- Women and Gender Relations

- World War II Literature, Jewish American

- Yankev Glatshteyn/Jacob Glatstein

- Yemen, The Jews of

- Yiddish Avant-garde Theater

- Yiddish Linguistics

- Yiddish Literature since 1800

- Yiddish Theater

- Ze’ev Jabotinsky

- Zionism from Its Inception to 1948

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|81.177.182.174]

- 81.177.182.174

Voices of Holocaust Survivors: Oral Histories and Personal Narratives

Updated 1/9/2023

Each year on January 27 the United Nations commemorates International Holocaust Remembrance Day .

Survivors’ personal stories are a powerful primary source for learning about the Holocaust. Explore the Library’s collection of oral histories, autobiographies, biographies, and memoirs of Holocaust survivors. Also available is a LibGuide, Holocaust Research, Education, and Remembrance Online , put together by Dorot Jewish Division Staff, outlining online resources at NYPL and beyond including research, curriculum, and multimedia resources.

Rena Grynblat, b. 1926, Warsaw, Poland. Image ID: 5164371

Oral Histories

Vladka Meed ( Feigele Pelte Miedzyrzecki ) was a teenager when the Nazis occupied Poland. Active in the underground youth movement, she lived as a Polish non-Jew in Warsaw, outside of the ghetto, and worked as a courier, carrying out illegal missions such as hiding people, smuggling documents, and organizing the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. She was the only one in her family to survive and came to the United States in 1946, writing a memoir about her experiences. Read her interview in our Digital Collections .

Egon Loebner was an accomplished student in Czechoslovakia, who dreamed of becoming a diplomat but chose engineering because he knew he would have to emigrate due to antisemitism. He survived the ghettos, the camps Theresienstadt and Auschwitz, and lost nearly his entire family. His engineering skills saved his life many times during the war. He later came to the U.S. where he met Albert Einstein and got Einstein's recommendation to study physics, helping to develop today’s flat screen televisions. Read his interview in our Digital Collections .

Maria Rosenbloom grew up in Kolomija in a wealthy and religious family. She battled antisemitic quotas and violence to study Polish literature in Lviv in the late 1930’s. During the Second World War, she lost her husband, parents, and virtually her entire family, in an atmosphere of horrific violence and starvation. She lived as a non-Jewish Pole but her Jewish appearance frequently put her life in danger and caused her to flee. She was shot while participating in resistance activities. Working with displaced persons after the war, she eventually became a leading psychiatric social worker and teacher. Read her interview in our Digital Collections .

Aryeh Neier was born in Berlin in 1937, the child of Galician Jews. His family fled to England just a few years later, where his father was held in an internment camp on suspicion of being a possible spy, and Aryeh lived in a home for refugee children for a year. Virtually all of his relatives in Germany and Poland were killed during the Holocaust. In London, their house was bombed. After the war, the family settled in New York. Aryeh studied labor relations at Cornell and became a well-known advocate for civil liberties and human rights. A prolific author and professor, his most famous and controversial case was ACLU’s defense of the Nazis’ right to march in Skokie . Read his interview in our Digital Collections.

The above individuals were interviewed for the American Jewish Committee Oral History Collection , which includes 2,250 individuals, among them approximately 250 Holocaust survivors. Read more oral histories of Holocaust survivors online and onsite . Search the catalog using the keywords “oral” and survivor” to find more.

Personal Narratives

Explore the Library’s collection of autobiographies, biographies, and memoirs of Holocaust survivors.

Search the catalog :

By call number : *PWZ - then click “modify search” and choose subject word “Holocaust”

Search for personal narratives by thematic subject heading :

- Holocaust, Jewish (1939-1945) -- Personal narratives

- World War, 1939-1945 -- Personal narratives

- World War, 1939-1945 -- Personal narratives, Jewish

Elie Wiesel is an award-winning author and professor. His most famous book, Night, is a memoir of his experience surviving the Holocaust as a teenager, and has been translated into more than 30 languages. Image ID: TH-64778

Yizkor Books

The Library’s collection includes approximately 700 yizkor books , memorial books of Jewish communities destroyed in the Holocaust. Yizkor books were largely written and compiled by survivors, and by landslayt (townspeople who had left before the war) and often include personal essays, memoirs and eyewitness accounts from wartime.

Search Jewish Gen’s bibliographic yizkor book database by the names of towns or cities, and check NYPL’s website for an alphabetical list of our yizkor book holdings. Read yizkor books online and onsite , and find English translations at JewishGen .

For yizkor book narratives of Holocaust survivors in Poland, see From A Ruined Garden: The Memorial Books of Polish Jewry , translated and edited by Jack Kugelmass and Jonathan Boyarin ; with geographical index and bibliography by Zachary M. Baker.

Zionist yeshiva, 1910. From the yizkor book of Lida, Belarus. Image ID: 5038825

Additional subject headings for Holocaust research

- World War, 1939-1945 -- Jewish resistance -- Poland.

- World War, 1939-1945 -- Jews -- Rescue.

- Righteous Gentiles in the Holocaust

- World War, 1939-1945 -- Underground movements.

- Gays -- Nazi persecution

- Jehovah’s witnesses -- Nazi persecution

- Jewish Women in the Holocaust

- World War, 1939-1945 -- Children .

- People with disabilities --Nazi persecutio n

- Romanies - Nazi persecution

Need additional research help? Contact us at [email protected]

Behind Every Name, Stories from the Holocaust

By examining true personal stories, told through short animations , students learn about unique individual experiences within the historical context of the Holocaust. This activity contains an extension to examine the role of artifacts in understanding history.

Grade level: Adaptable for grades 7-12 Subject: Multidisciplinary Time required: 20 minutes, with optional artifact extension Languages : English, Español

For Learning Management Systems

This online lesson plan is compatible with learning management systems or web browsers for students to complete individually or as a class. You can use the PDF of the original lesson plan above as a guide. To use with your LMS, download the files below and follow your system’s instructions for importing files.

Online lesson link (for web browsers)

SCORM 1.2 (ZIP)

SCORM 2004 (ZIP)

xAPI (Tin Can) (ZIP)

This lesson is also available in Spanish.

This Section

Explore lesson plans and training materials organized by theme to use in your classroom.

- Online Tools for Learning and Teaching

- Videos for Classroom Use

- Entertainment

- <i>We Were the Lucky Ones</i> Comes So Close to Transcending the Typical Holocaust Drama

We Were the Lucky Ones Comes So Close to Transcending the Typical Holocaust Drama

A mong the many misperceptions about the Holocaust that well-meaning Hollywood creators have unwittingly perpetuated, the most damaging has been the idea that Jews were passive victims, complacently herded into airless train cars to be exterminated at death camps. Bloody revenge fantasies like Quentin Tarantino ’s Inglourious Basterds aside, realistic accounts of Jewish self-defense in the face of Nazi annihilation have been few and far between. We Were the Lucky Ones , Hulu’s eight-part adaptation of the novel by Georgia Hunter, provides a rare counter-narrative of courageous resistance. Yet it still falls prey to many of the tear-jerking, experience-flattening conventions that rob so much Holocaust fiction of specificity and insight.

Premiering March 28, Lucky Ones spans nearly a decade in the lives of the Kurcs, a big, affectionate, upper-middle-class Jewish family based in Radom, Poland. We meet them in 1938, on the day Addy (Logan Lerman), a composer of some renown in Paris, arrives at his parents’ (Robin Weigert and Lior Ashkenazi) apartment for Passover. His sister Mila (Hadas Yaron) is expecting her first child with her husband, Selim (Michael Aloni). Their brother Jakob (Amit Rahav) seems more passionate about his girlfriend, Bella (Eva Feiler), than he is about his studies in law school. Eldest child Genek (Henry Lloyd-Hughes) is their father’s protégé and confidant.

With apologies to Addy, the family’s real hero is youngest daughter Halina, a clever, willful, vivacious young woman played by The Act and The Kissing Booth star Joey King . She’s got her eye on the architect lodger her parents have taken in, Adam (Sam Woolf), perhaps in the hope of forging a love connection. More urgent, in her mind, is her search for a direction in life. After nervous whispers about a spike in local antisemitism presage Germany’s sudden invasion of Poland, Halina finds that purpose in working for the anti-Nazi resistance—and, more so, in scrambling to keep her parents and siblings safe. As the years go on and the persecution Jews face intensifies, she will lie, bribe, fight, scheme, embark upon long, perilous journeys, and endure all manner of torture in a tireless quest to ensure that the Kurcs survive the Holocaust.

Although it’s based on a true story, Lucky Ones verges on unbelievability in its depiction of the sheer variety of World War II-era horrors the Kurcs survive, across four continents. Some depart for Soviet-controlled Lvov, to take their chances with Stalin; a storyline set at a grueling Siberian work camp follows. Those who stay in Radom see their homes seized, their jobs eliminated, their businesses stolen. After the Nazis invade France, Addy winds up on a boat headed for Brazil—but there will be many unanticipated stops on his voyage to freedom. Meanwhile, there are pogroms, ghettos, firing squads, Jews posing as virulently antisemitic gentiles, nuns paid to hide a young child at an orphanage, brief glimpses inside concentration camps and at Senegal under Vichy rule.

The breadth of experiences the series depicts, and its concentration on Jews who did not go quietly from their living rooms to the gas chambers, could make it a useful teaching tool. Which is not to say it’s dry; I was in tears for much of the finale, thanks to performances that are universally convincing and in some cases, like King’s and Lerman’s, excellent. (I do wish Weigert, who’s been brilliant in shows like Deadwood and Jessica Jones , had been given more to do.) And while it can be confusing to watch characters speak Polish-accented English in Radom and French-accented English in Paris for the sake of subtitle-wary American audiences, I appreciate showrunner Erica Lipez’s ( The Morning Show ) choice not to over-explain Jewish culture.

Despite its many virtues, Lucky Ones falls into the same traps as too many other Holocaust dramas. The script can be quite lazy, filled with whole sentences we’ve heard before: “All of Europe has gone mad.” “Why won’t you let me love you?” “The Germans are coming!” There are so many Kurcs, each with their own significant other, that everyone besides Halina and Addy can seem interchangeable. This is, in part, due to the noble yet nonspecific personality with which each is endowed by virtue of being a Jewish character in a show about the Holocaust. And when a Kurc survives where we watch other, anonymous Jews perish, the likely inadvertent but nonetheless offensive implication is that they’re superior to the millions across Europe who weren’t so lucky—smarter, tougher, more empowered by their love for one another.

Anyone with a functioning heart will find this family’s story moving. Viewers whose education on the Holocaust has come solely from Hollywood might even find it enlightening. What it lacks, as a work of art (it would be grotesque to call it a work of entertainment), is the level of insight that might justify putting us through eight hours’ worth of human misery. What does it mean that not just the Nazis, but essentially the entire world, made it impossible for Jews to find safety during World War II? How does the Kurcs’ saga speak to the world’s current refugee crises? How does it mirror the family separations that happen at the United States’ own southern border? With so many Holocaust dramas, on screens big and small, vying to yank our heart strings, the bar for a truly crucial example is high. We Were the Lucky Ones comes close but doesn’t clear it.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Jane Fonda Champions Climate Action for Every Generation

- Passengers Are Flying up to 30 Hours to See Four Minutes of the Eclipse

- Biden’s Campaign Is In Trouble. Will the Turnaround Plan Work?

- Essay: The Complicated Dread of Early Spring

- Why Walking Isn’t Enough When It Comes to Exercise

- The Financial Influencers Women Actually Want to Listen To

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

You May Also Like

Search the Holocaust Encyclopedia

- Animated Map

- Discussion Question

- Media Essay

- Oral History

- Timeline Event

- Clear Selections

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Português do Brasil

Featured Content

Find topics of interest and explore encyclopedia content related to those topics

Find articles, photos, maps, films, and more listed alphabetically

For Teachers

Recommended resources and topics if you have limited time to teach about the Holocaust

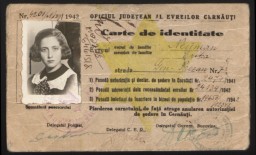

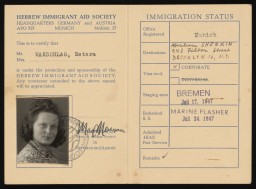

Explore the ID Cards to learn more about personal experiences during the Holocaust

Timeline of Events

Explore a timeline of events that occurred before, during, and after the Holocaust.

- Introduction to the Holocaust

- Liberation of Nazi Camps

- Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

- Boycott of Jewish Businesses

- Axis Invasion of Yugoslavia

- Antisemitism

- How Many People did the Nazis Murder?

- The Rwanda Genocide

Series: In Their Own Words: Holocaust Survivor Testimonies

What was it like to live through the Holocaust? Learn about individuals' experiences, actions, and choices from survivors themselves. Listen to excerpts from their oral testimonies. Browse transcripts of the recordings. And get to know the featured survivors by reading their biographies.

David Bayer

Erika Eckstut

Gideon Frieder

Manya Friedman

Estelle laughlin.

Frank Liebermann

Jacob Wiener

Martin Weiss

Thank you for supporting our work.

We would like to thank Crown Family Philanthropies and the Abe and Ida Cooper Foundation for supporting the ongoing work to create content and resources for the Holocaust Encyclopedia. View the list of all donors .

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Share. Behind Every Name a Story consists of essays describing survivors' experiences during the Holocaust, written by survivors or their families. The essays, accompanying photographs, and other materials, including submissions that we are unable to feature on our website, will become a permanent part of the Museum's records.

The Holocaust and the Literary Imagination. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1975. Argues that Holocaust literature cannot be regarded as the exclusive domain of the victims alone, or even Jewish writers. An early study of the "art of atrocity.". The volume contrasts with Lang's more proscriptive style of criticism.

In Auschwitz death did not happen at the end; it was present at all times and everywhere. One of the essays in the collection is on death. There's a quote from a survivor: "not only is life and human dignity violated here but human death counts for nothing.". For us, death is so tragic. It's a big mystery.

Anne Frank's The Diary of a Young Girl (1947) is probably the one Holocaust book most people have heard of. It charts the two years Anne and her family spent in hiding in Amsterdam. The book is ...

Voices: The 1946 Holocaust Interviews of David Boder (2010) and the Sounds of Defiance:The Holocaust, Multilingualism, and theProblem of English (2005),editor ofApproachestoTeachingWiesel'sNight(2007), and co-editor of Elie Wiesel: Jewish, Moral, and Literary Perspectives (2013). He lectures regularly on Holocaust literature at Yad Vashem's

The Holocaust. The Holocaust was one of the worst genocides in history, in which Adolph Hitler's Nazi Germany sought to exterminate the Jewish and Roma/Sinti peoples in Europe and North Africa. The genocide killed over six million Jews, one million Roma and Sinti, and apx. four million others deemed undesirable to the Third Reich during World ...

The guide to Holocaust literature places texts in historical context, encouraging students to understand how and why the Holocaust happened. Grade level: Adaptable for grades 7-12 Subject: English/Language Arts Time required: Approximately 60 minutes to introduce Before the Reading. Student work continues while they read the text.

The title of the book suggests Rosenfeld's main point that the Holocaust killed not only men, but also the "idea of man." Young, James E. Writing and Rewriting the Holocaust: Narrative and the Consequences of Interpretation. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988. Historiographical work that interprets the meaning of Holocaust ...

Trauma and Literature - March 2018. To save this book to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account.

Description. Holocaust Narratives: Trauma, Memory and Identity Across Generations analyzes individual multi-generational frameworks of Holocaust trauma to answer one essential question: How do these narratives change to not only transmit the trauma of the Holocaust - and in the process add meaning to what is inherently an event that ...

Preface Acknowledgements Introduction: Narrative and the Consequences of Interpretation I. Interpreting Literary Testimony 1. On Rereading Holocaust Diaries and Memoirs 2. From Witness to Legend: Tales of the Holocaust 3. Holocaust Documentary Fiction: Novelist as Eyewitness 4. Documentary Theater, Ideology, and the Rhetoric of Face II. Figuring and Refiguring the Holocaust: Interpreting ...

A Narrative Essay On The Holocaust. 50 years ago, my family was taken from our home and torn apart. It has been 39 years since my husband died and I had lost my only child forever. It has been 38 years since I became a survivor of the holocaust. We were just sitting down to dinner; my husband and I had invited my parents to dinner to tell them ...

Current Perspectives on the Holocaust : Review Essay. Van Pelt incorporated this issue into the. ingredient of their discussion, and underscored more fully than can be seen in the Dawidowicz. was a very important issue, but by bringing and van Pelt treatment is much more complete. approaches to the Holocaust.

Introduction: The Ethics of Imagining the Holocaust: Representation, Responsibility, and Reading PART I: MEMOIRS The Ethics of Reading Wiesel's Night Painful Memories: The Agony of Primo Levi World Into Words: The Diary of Anne Frank and Sophie Goetzel-Leviathan's The War from Within PART II: REALISM Tadeusz Borowski's This Way to the Gas Chambers, Ladies and Gentlemen, and Other Stories John ...

Yizkor Books. The Library's collection includes approximately 700 yizkor books, memorial books of Jewish communities destroyed in the Holocaust.Yizkor books were largely written and compiled by survivors, and by landslayt (townspeople who had left before the war) and often include personal essays, memoirs and eyewitness accounts from wartime.

What was the Holocaust? The Holocaust (1933-1945) was the systematic, state-sponsored persecution and murder of six million European Jews by the Nazi German regime and its allies and collaborators. 1 The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum defines the years of the Holocaust as 1933-1945. The Holocaust era began in January 1933 when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party came to power in Germany.

Personal Narrative Essay on Hearing a Holocaust Story. This essay sample was donated by a student to help the academic community. Papers provided by EduBirdie writers usually outdo students' samples. After reading "Night" by Elie Wiesel I have gotten a far better understanding of the treatment and handling of Jews during the Holocaust, and ...

Holocaust Narrative through Historical Photos. This lesson provides a method of assessing what students know and how they think about the Holocaust. Through interacting with a range of historical photographs and images, students generate questions that can then lead to more productive lesson planning. Grade level: Adaptable for grades 7-12 ...

From the publisher's description:This resource guide will help readers locate over 800 first-person accounts, fiction, poetry, art interpretations, and music by Holocaust victims and survivors, as well as videos relating the testimony and experiences of Holocaust survivors.The work is divided into five parts: writers of memoirs, diaries and fiction; poets; artists; composers and musicians; and ...

Holocaust Narrative Essay. On October 7th, 1944 a Jewish prisoner group,"special detachment", revolted and blew up Crematorium IV killing many guards. I felt a spark of hope coming and all I could think that there was a chance to stop all of this. Sadly, my hopes we destroyed almost immediately.

Narrative Essay On The Holocaust. I am and SS officer. I was stationed at Auschwitz. More Jews were coming in every day. There were eighty to a cattle cart. There were so many families that had to go separate ways from one another. I had killed mothers and the babies and weakest of the men that couldn't work. It was horrible, I do say.

Behind Every Name, Stories from the Holocaust. By examining true personal stories, told through short animations, students learn about unique individual experiences within the historical context of the Holocaust. This activity contains an extension to examine the role of artifacts in understanding history. Grade level: Adaptable for grades 7-12 ...

With so many Holocaust dramas, on screens big and small, vying to yank our heart strings, the bar for a truly crucial example is high. We Were the Lucky Ones comes close but doesn't clear it.

Media Essay Oral History Photo Series Song ... Recommended resources and topics if you have limited time to teach about the Holocaust. ID Cards. Explore the ID Cards to learn more about personal experiences during the Holocaust. Timeline of Events. Explore a timeline of events that occurred before, during, and after the Holocaust. ...