Access your Commentary account.

Lost your password? Please enter your email address. You will receive a link to create a new password via email.

The monthly magazine of opinion.

The Price of the Ticket, by James Baldwin

The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction 1948-1985. by James Baldwin. St. Martin's. 704 pp. $29.95.

“The failure of the protest novel,” James Baldwin wrote in 1949, “lies in its rejection of life, the human being, the denial of his beauty, dread, power, in its insistence that it is his categorization alone which is real and which cannot be transcended.” It was around this time that American critics first began to speak of Baldwin as a writer with the sensibility and detachment of a potentially first-rate artist; with the 1953 publication of Go Tell It on the Mountain , a beautifully written first novel about Harlem life, he proved them correct.

That book, together with the best of his early essays for COMMENTARY and Partisan Review , quickly gave James Baldwin a well-deserved reputation as an outstandingly gifted writer—and the only black writer in America capable of staying out of what Lionel Trilling called in another connection “the bloody crossroads” between literary art and politics. Soon his name began to appear regularly in middlebrow magazines like Harper's and the New Yorker .

But Baldwin's qualifications for playing the “Great Black Hope,” as he later characterized his role, began to look a little more problematic with each passing year. He had, after all, abandoned Harlem for Paris with what looked suspiciously like enthusiasm. His ornate prose style reminded readers more of Henry James than of Richard Wright. And he was, though he did not advertise it at first, a homosexual. None of this seemed to have much to do with the kinds of things people like Martin Luther King, on the one hand, or Malcolm X, on the other hand, were saying in public. Younger and more militant blacks took elaborate pains to distance themselves from Baldwin; Eldridge Cleaver, in Soul on Ice , went so far as to accuse Baldwin of harboring a “shameful, fanatical, fawning, sycophantic love of the whites.”

Eventually, perhaps in response to such criticism, the tone of Baldwin's work began to take on a raw, politicized stridency which had not previously been a part of his literary equipment. This stridency fatally compromised his standing as a writer of fiction; Another Country was the last of his novels to be taken at all seriously by the critics (and by no means all of them). But Baldwin's essays, early and late, have somehow remained impervious to revaluation—which makes it all the more useful to have this new volume of his “collected nonfiction.”

The Price of the Ticket contains, complete and unabridged, Notes of a Native Son; Nobody Knows My Name; The Fire Next Time; Nothing Personal; The Devil Finds Work; No Name in the Street; and a couple of dozen previously uncollected articles of largely exiguous interest. The only important omissions are the autobiographical preface to Notes of a Native Son and Baldwin's latest book, an essay on the Atlanta child murders called The Evidence of Things Not Seen . 1 It is a fat omnibus, clearly a gesture to posterity, and an attempt to consolidate Baldwin's shaky literary reputation. Times and tastes have changed profoundly since Baldwin published his first important essay in COMMENTARY forty-odd years ago, and so one inevitably wonders: does he still sound like a major writer? Is the literary value of his work compromised by his consuming obsession with race? Is his message as compelling as ever—or simply irrelevant?

Baldwin's first collection of essays, Notes of a Native Son (1955), was received with more or less uncritical admiration (in a typical comment Alfred Kazin wrote: “ Notes of a Native Son . . . is the work of an original literary talent who operates with as much power in the essay form as I've ever seen”). But Notes of a Native Son is likely to strike today's reader as uneven in a way that Baldwin's first novel, for all its flaws, is not. Baldwin spends the whole first part of the book searching for the right things to write about and the right tone in which to write about them. Though he is reasonably competent at it, straight reportage obviously does not become him; as for his initial attempts at literary criticism, these come out sounding hopelessly stilted.

What finally pulled Baldwin's nonfiction writing up to the level of the best parts of Go Tell It on the Mountain was his discovery, in a 1953 essay (also collected in Notes of a Native Son ), “Stranger in the Village,” of the great good pronoun of his literary destiny: the concrete, liberating “I” which, as with Proust's “Marcel,” would bring his idiosyncratic style into the sharpest focus. In this piece Baldwin finally learned to do in his writing what, as a budding young preacher in Harlem, he must have heard about in the cradle: to begin with anecdote and end in generalization:

From all available evidence no black man had ever set foot in this tiny Swiss village before I came. I was told before arriving that I would probably be a “sight” for the village; I took this to mean that people of my complexion were rarely seen in Switzerland, and also that city people are always something of a “sight” outside the city. It did not occur to me—possibly because I am an American—that there could be people anywhere who had never seen a Negro.

With the simple but pregnant discovery of autobiography as a vehicle for social criticism, Baldwin had at last struck a workable balance between the two most characteristic aspects of his artistic personality, the fiery Harlem preacher and the urbane Parisian memoirist. In the 1955 essays “Equal in Paris” and “Notes of a Native Son,” both written in the first person, it is the latter aspect which dominates; these two pieces, like Go Tell It on the Mountain , are devoid of an overtly political content, and the author's angry message emerges through stylish dramatized narrative rather than vague sermonizing:

My friend stayed outside the restaurant long enough to misdirect my pursuers and the police, who arrived, he told me, at once. I do not know what I said to him when he came to my room that night. I could not have said much. I felt, in the oddest, most awful way, that I had somehow betrayed him. . . . I could not get over two facts, both equally difficult for one imagination to grasp, and one was that I could have been murdered. But the other was that I had been ready to commit murder. I saw nothing very clearly but I did see this: that my life, my real life, was in danger, and not from anything other people might do but from the hatred I carried in my own heart.

“Equal in Paris” and “Notes of a Native Son” come close to justifying every word of praise ever uttered about Notes of a Native Son . On the other hand, Baldwin's second collection, Nobody Knows My Name , which also received high praise, contains nothing that comes anywhere near matching the remarkable quality of those two essays. Baldwin largely restricts himself here to reportage about the desperate condition of Southern blacks; while these articles are, as reportage, far more professional than their earlier counterparts in Notes of a Native Son , their literary value is strictly that of good celebrity journalism. And when Baldwin does use explicitly autobiographical material, the results, particularly in “The Black Boy Looks at the White Boy,” are diminished by a distressing new quality: an extreme, even mannered, self-consciousness.

_____________

Yet whatever may have been wrong with Nobody Knows My Name , readers of the November 17, 1962 New Yorker who opened their copies in order to read a report by James Baldwin on the Black Muslims called “Letter from a Region in My Mind” suddenly found in their hands the literary equivalent of a pinless grenade. The opening paragraph of this extraordinary essay, which quickly found its way between hard covers as The Fire Next Time , was riveting:

I underwent, during the summer that I became fourteen, a prolonged religious crisis. I use the word “religious” in the common, and arbitrary, sense, meaning that I then discovered God, His saints and angels, and His blazing Hell. And since I had been born in a Christian nation, I accepted this Deity as the only one. I supposed Him to exist only within the walls of a church—in fact, of our church—and I also supposed that God and safety were synonymous. . . .

Baldwin, describing the religion of his youth with incomparable vividness, concludes in The Fire Next Time that it is no longer sufficient. In light of the long history of racism, “whoever wishes to become a truly moral human being . . . must first divorce himself from all the prohibitions, crimes, and hypocrisies of the Christian church.” He interprets the rise of the Black Muslims, who preach that Allah is black and the white man the devil, as the predictable outcome of the moral decadence of Christianity, though he rejects the simple-minded demonology and racial separatism of Elijah Muhammad and Malcolm X, he finds in it rough justice for the sins of the white man. The situation, however, is not altogether hopeless:

If we—and now I mean the relatively conscious whites and the relatively conscious blacks, who must, like lovers, insist on, or create, the consciousness of the others—do not falter in our duty now, we may be able, handful that we are, to end the racial nightmare, and achieve our country, and change the history of the world. If we do not now dare everything, the fulfillment of that prophecy, recreated from the Bible in song by a slave, is upon us: “God gave Noah the rainbow sign, No more water, the Fire next time!”

The Fire Next Time is not without its stylistic miscalculations, the worst of which is “My Dungeon Shook,” a four-page preface bearing the subtitle “Letter to My Nephew on the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Emancipation” and through whose resolute platitudes one slogs with dismay. But Baldwin's writing in the rest of The Fire Next Time is generally quite marvelous. It is, in fact, so good that something like an act of will is needed to ask the key question: what is being said here? What is being recommended?

“I was always exasperated by his notions of society, politics, and history,” James Baldwin once said of Richard Wright, “for they seemed to me to be utterly fanciful.” These harsh words are even more readily applicable to Baldwin himself, who is in a very real sense a man with neither politics nor philosophy. The political impact of his best work was previously achieved through implication alone; The Fire Next Time reveals that his specific responses to the condition of blacks in America are wholly emotional. F.W. Dupee was one of the few critics who attempted to find the substance in Baldwin's gorgeously inflammatory prose, and his essay on The Fire Next Time clearly demonstrates the extent to which the book's “message” can be reduced to a string of meaningless generalzations:

For example: “White Americans do not believe in death, and this is why the darkness of my skin so intimidates them.” But suppose one or two white Americans are not intimidated. Suppose someone coolly asks what it means to “believe in death.” Again: “Do I really want to be integrated into a burning house?” Since you have no other, yes; and the better-disposed firemen will welcome your assistance. . . . Again: “The real reason that nonviolence is considered to be a virtue in Negroes . . . is that white men do not want their lives, their self-image, or their property threatened.” Of course they don't, especially their lives. Moreover, this imputing of “real reasons” for the behavior of entire populations is self-defeating, to put it mildly.

Despite its still formidable reputation as a central document in the struggle for equality, The Fire Next Time turns out to have little of interest to say about the question of racial politics. Its impact comes solely from the fact that it is so exquisitely written. And Baldwin's timing was immaculate. His passionate prophecies of impending doom scorched the collective consciousness of middle-class Americans in a way that no amount of sober analysis could have rivaled.

But The Fire Next Time was the last point at which the curve of James Baldwin's career intersected with the Zeitgeist of the Great Society. Public black rhetoric came to be dominated, just as Baldwin had predicted it would, by loveless images of violence. And Baldwin's response to this change was, to say the least, disheartening.

Though The Fire Next Time was full of the language of extremism, its message was not yet one of racial hate. That was still to come. In No Name in the Street , his 1972 sequel to The Fire Next Time , Baldwin's striking prose style, that arresting amalgam of Henry James and the Old Testament, remained largely intact. But the ends to which he now directed this style were another matter altogether. For even the most casual reading of No Name in the Street revealed that the literary control manifested in The Fire Next Time had now been coarsened by aimless, free-floating political hysteria.

The best and worst of this disturbing book can be found in a single brilliantly staged scene which is just fantastic enough to be true. Baldwin, shortly after Martin Luther King's assassination, tells the columnist Leonard Lyons that he will never again be able to wear the suit he wore to the King funeral; Lyons duly publishes the item. A few weeks later, Baldwin receives a call from the man who was his best friend in junior high school and whom he has not seen since. “He could not afford to have suits in his closet which he didn't wear,” Baldwin explains, “he couldn't afford my elegant despair. Martin was dead, but he was living, he needed a suit, and—I was just his size.” An exchange is proposed: one used suit for one home-cooked dinner in Harlem. With cold and terrifying detachment Baldwin describes an evening in the “small, dark, unspeakably respectable, incredibly hard-won rooms” of his old friend, meticulously recording every agonizing detail of the mutual discomfort of old friends who have grown apart. And then the conversation turns to the war in Vietnam:

I told him that Americans had no business at all in Vietnam; and that black people certainly had no business there, aiding the slave master to enslave yet more millions of dark people, and also identifying themselves with the white American crimes. . . . It wasn't, I said, hard to understand why a black boy, standing, futureless, on the corner, would decide to join the Army, nor was it hard to decipher the slave master's reasons for hoping that he wouldn't live to come home, with a gun; but it wasn't necessary, after all, to defend it: to defend, that is, one's murder and one's murderers. “Wait a minute,” he said, “let me stand up and tell you what I think we're trying to do there.” “ We ?” I cried, “what motherfucking we ? You stand up, motherfucker, and I'll kick you in the ass!”

After a career spent dancing in and out of “the bloody crossroads,” Baldwin had at last faltered. The lapse was to be permanent. Aside from The Devil Finds Work , an erratic and frequently embarrassing volume of autobiography masquerading as film criticism, he published only a handful of political essays after No Name in the Street . They are shocking in their abandonment of all pretense to literary detachment; in them Baldwin luxuriates in the foul rhetoric of zealotry that for more than a decade poisoned this country's political discourse:

Therefore, in a couple of days, blacks may be using the vote to outwit the Final Solution. Yes. The Final Solution. No black person can afford to forget that the history of this country is genocidal from where the buffalo once roamed to where our ancestors were slaughtered (from New Orleans to New York, from Birmingham to Boston) and to the Caribbean to Hiroshima and Nagasaki to Saigon. Oh, yes, let freedom ring.

One hates to see such mindless fatuities (published originally in the Nation ) under the byline of the man who wrote “Equal in Paris” and “Notes of a Native Son.”

It is impossible to read the second half of The Price of the Ticket without feeling an intense sadness at the literary tragedy it embodies. And it is equally difficult to read the rest of the book without coming to feel that of its seven hundred pages one would willingly, even gratefully, part with all but The Fire Next Time and a handful of shorter essays. To revisit James Baldwin's nonfiction is to understand the full extent to which the trivializing claims of radical politics undermined the artistic career of the man about whom Edmund Wilson once said: “He is not only one of the best Negro writers that we have ever had in this country, he is one of the best writers that we have.”

1 Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 125 pp., $11.95.

Joan Didion From the Couch

Brush Off Your Shakespeare

Joseph Epstein’s Brief for the Novel

Scroll Down For the Next Article

Type and press enter

- More Networks

- Literature & Fiction

- History & Criticism

Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) is a service we offer sellers that lets them store their products in Amazon's fulfillment centers, and we directly pack, ship, and provide customer service for these products. Something we hope you'll especially enjoy: FBA items qualify for FREE Shipping and Amazon Prime.

If you're a seller, Fulfillment by Amazon can help you grow your business. Learn more about the program.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction, 1948-1985 Hardcover – September 15, 1985

- Print length 704 pages

- Language English

- Publisher St. Martin's Press

- Publication date September 15, 1985

- Dimensions 6.5 x 2 x 9.5 inches

- ISBN-10 0312643063

- ISBN-13 978-0312643065

- See all details

Similar items that may ship from close to you

Editorial Reviews

About the author, product details.

- Publisher : St. Martin's Press; 1st edition (September 15, 1985)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 704 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0312643063

- ISBN-13 : 978-0312643065

- Item Weight : 2.45 pounds

- Dimensions : 6.5 x 2 x 9.5 inches

- #434 in Black & African American Literary Criticism (Books)

- #6,297 in Literary Criticism & Theory

- #19,390 in Sociology (Books)

About the author

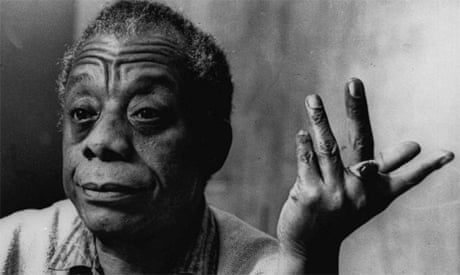

James baldwin.

James Baldwin (1924-1987) was a novelist, essayist, playwright, poet, and social critic, and one of America's foremost writers. His essays, such as "Notes of a Native Son" (1955), explore palpable yet unspoken intricacies of racial, sexual, and class distinctions in Western societies, most notably in mid-twentieth-century America. A Harlem, New York, native, he primarily made his home in the south of France.

His novels include Giovanni's Room (1956), about a white American expatriate who must come to terms with his homosexuality, and Another Country (1962), about racial and gay sexual tensions among New York intellectuals. His inclusion of gay themes resulted in much savage criticism from the black community. Going to Meet the Man (1965) and Tell Me How Long the Train's Been Gone (1968) provided powerful descriptions of American racism. As an openly gay man, he became increasingly outspoken in condemning discrimination against lesbian and gay people.

Photo by Allan warren (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons.

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Start Selling with Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

James Baldwin on the Creative Process and the Artist’s Responsibility to Society

By maria popova.

In a 1962 essay titled “The Creative Process,” found in the altogether fantastic anthology The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction ( public library ), Baldwin lays out a manifesto of sorts, nuanced and dimensional yet exploding with clarity of conviction, for the trying but vital responsibility that artists, “a breed of men and women historically despised while living and acclaimed when safely dead,” have to their society.

Baldwin, only thirty-eight at the time, writes:

Perhaps the primary distinction of the artist is that he must actively cultivate that state which most men, necessarily, must avoid: the state of being alone. That all men are, when the chips are down, alone, is a banality — a banality because it is very frequently stated, but very rarely, on the evidence, believed. Most of us are not compelled to linger with the knowledge of our aloneness, for it is a knowledge that can paralyze all action in this world. There are, forever, swamps to be drained, cities to be created, mines to be exploited, children to be fed. None of these things can be done alone. But the conquest of the physical world is not man’s only duty. He is also enjoined to conquer the great wilderness of himself. The precise role of the artist, then, is to illuminate that darkness, blaze roads through that vast forest, so that we will not, in all our doing, lose sight of its purpose, which is, after all, to make the world a more human dwelling place.

But unlike David Foster Wallace’s heartbreaking and rather matter-of-fact observation — “I’m going to die, and die very much alone, and the rest of the world is going to go merrily on without me.” — Baldwin is careful to point out that this ideal aloneness is not a state of nihilistic resignation but a prerequisite for realizing and inhabiting one’s true identity, rather than donning an identity inherited from society like a traditional costume:

The state of being alone is not meant to bring to mind merely a rustic musing beside some silver lake. The aloneness of which I speak is much more like the aloneness of birth or death. It is like the fearless alone that one sees in the eyes of someone who is suffering, whom we cannot help. Or it is like the aloneness of love, the force and mystery that so many have extolled and so many have cursed, but which no one has ever understood or ever really been able to control. I put the matter this way, not out of any desire to create pity for the artist — God forbid! — but to suggest how nearly, after all, is his state the state of everyone, and in an attempt to make vivid his endeavor. The state of birth, suffering, love, and death are extreme states — extreme, universal, and inescapable. We all know this, but we would rather not know it. The artist is present to correct the delusions to which we fall prey in our attempts to avoid this knowledge. It is for this reason that all societies have battled with the incorrigible disturber of the peace — the artist. I doubt that future societies will get on with him any better. The entire purpose of society is to create a bulwark against the inner and the outer chaos, in order to make life bearable and to keep the human race alive. And it is absolutely inevitable that when a tradition has been evolved, whatever the tradition is, the people, in general, will suppose it to have existed from before the beginning of time and will be most unwilling and indeed unable to conceive of any changes in it. They do not know how they will live without those traditions that have given them their identity. Their reaction, when it is suggested that they can or that they must, is panic… And a higher level of consciousness among the people is the only hope we have, now or in the future, of minimizing human damage.

In a sentiment that Jeanette Winterson would come to echo decades later — “Art … says, don’t accept things for their face value; you don’t have to go along with any of this; you can think for yourself.” — Baldwin considers the unique position of the artist as a challenger of society’s protective delusions :

The artist is distinguished from all other responsible actors in society — the politicians, legislators, educators, and scientists — by the fact that he is his own test tube, his own laboratory, working according to very rigorous rules, however unstated these may be, and cannot allow any consideration to supersede his responsibility to reveal all that he can possibly discover concerning the mystery of the human being. Society must accept some things as real; but he must always know that visible reality hides a deeper one, and that all our action and achievement rest on things unseen. A society must assume that it is stable, but the artist must know, and he must let us know, that there is nothing stable under heaven. One cannot possibly build a school, teach a child, or drive a car without taking some things for granted. The artist cannot and must not take anything for granted, but must drive to the heart of every answer and expose the question the answer hides.

But the artist’s responsibility to society springs from the artist’s responsibility to him- or herself. Reflecting on the monumental challenge of self-awareness and the notion that “we hardly know our own depths,” Baldwin considers the elusive art of knowing ourselves, which we often evade by seeking to know others instead:

Anyone who has ever been compelled to think about it — anyone, for example, who has ever been in love — knows that the one face that one can never see is one’s own face. One’s lover — or one’s brother, or one’s enemy — sees the face you wear, and this face can elicit the most extraordinary reactions. We do the things we do and feel what we feel essentially because we must — we are responsible for our actions, but we rarely understand them. It goes without saying, I believe, that if we understood ourselves better, we would damage ourselves less. But the barrier between oneself and one’s knowledge of oneself is high indeed. There are so many things one would rather not know! We become social creatures because we cannot live any other way. But in order to become social, there are a great many other things that we must not become, and we are frightened, all of us, of these forces within us that perpetually menace our precarious security. Yet the forces are there: we cannot will them away. All we can do is learn to live with them. And we cannot learn this unless we are willing to tell the truth about ourselves, and the truth about us is always at variance with what we wish to be. The human effort is to bring these two realities into a relationship resembling reconciliation.

His words ring with double poignancy, for Baldwin — a queer Black man — came of age decades before the marriage equality movement and penned this essay a year before the March of Washington, at which Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech. Echoing throughout his manifesto for artists is Baldwin’s clarion call for acceptance of all who appear dissonant with society’s forces, for granting equal dignity to the human experience in all of its manifestations:

The human beings whom we respect the most, after all — and sometimes fear the most — are those who are most deeply involved in this delicate and strenuous effort, for they have the unshakable authority that comes only from having looked on and endured and survived the worst. That nation is healthiest which has the least necessity to distrust or ostracize these people — whom, as I say, honor, once they are gone, because somewhere in our hearts we know that we cannot live without them.

Baldwin closes by reflecting on this relationship between the artist and the nation, specifically in the context of American history. In a sentiment that calls to mind Susan Sontag on courage and resistance , he appeals to the artist’s most crucial, most challenging responsibility to culture:

In the same way that to become a social human being one modifies and suppresses and, ultimately, without great courage, lies to oneself about all one’s interior, uncharted chaos, so have we, as a nation, modified or suppressed and lied about all the darker forces in our history. […] Societies never know it, but the war of an artist with his society is a lover’s war, and he does, at his best, what lovers do, which is to reveal the beloved to himself and, with that revelation, to make freedom real.

The remaining essays in The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction explore, with the same blend of intellectual vigor and social sensitivity, subjects like power, protest, equality, patriotism, and the value of indignation. Complement this particular essay with Joseph Conrad on writing and the role of the artist .

Thanks, Morley

— Published August 20, 2014 — https://www.themarginalian.org/2014/08/20/james-baldwin-the-creative-process/ —

www.themarginalian.org

PRINT ARTICLE

Email article, filed under, art books creativity culture james baldwin lgbt out of print, view full site.

The Marginalian participates in the Bookshop.org and Amazon.com affiliate programs, designed to provide a means for sites to earn commissions by linking to books. In more human terms, this means that whenever you buy a book from a link here, I receive a small percentage of its price, which goes straight back into my own colossal biblioexpenses. Privacy policy . (TLDR: You're safe — there are no nefarious "third parties" lurking on my watch or shedding crumbs of the "cookies" the rest of the internet uses.)

James Baldwin: The Price of the Ticket

By Allan warren CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Novelist, essayist, playwright, activist, son, brother, friend, lover, man, human, Black. There are many words of which to describe a person, but never enough of which to describe someone who poured their heart and soul like James Baldwin .

Baldwin allowed his readers to explore the depths of his own humanity and the paths of his imaginations in his own words. His talent to express through writing did not only offered a peak into own life, but the stories of those who are afraid to tell their own. He did this through works such as: Giovanni’s Room , Go Tell It on the Mountain , Another Country , The Fire Next Time , and many others.

One of the most prevalent themes of Baldwin’s writings, was race. It is most evident in The Price of a Ticket , a collection of Baldwin’s most powerful essays exploring the social interaction of race, particularly in America.

Baldwin’s own rhetoric, as impactful as it was, was not enough to truly capture his own essence. It was through the 1989 documentary, James Baldwin: The Price of a Ticket , that we are able truly see Baldwin for who he was, and what he stood for. Through the intimate interviews on behalf of family members, friends, and of Baldwin himself, we witness his complexities and his attempt to navigate through a world of which he believed that “all men are brothers.”

This documentary, re-mastered in a 2K HD version, will be shown for the first time at the at Schomburg since 1989 during a special presentation on behalf of the the Schomburg Center and Maysles Cinema , April 6, 2016 at 6:30PM.

- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

THE PRICE OF THE TICKET

Collected nonfiction 1948-1985.

by James Baldwin ‧ RELEASE DATE: Oct. 28, 1985

Perhaps only a young black writer as prickly as the early Baldwin himself should review this, though at first it seems unreviewable by a black of any age, since Baldwin begins by rejecting blackness or negritude itself as a self-defeating, even strangling self-categorization. His strategy from the start has been to paint himself ever more tightly into a comer defined by everything he rejects (at one time or another, just about everything). With the sole exception of his 1985 book on the Atlanta child murders, this volume brings together every piece of nonfiction, short and long, that Baldwin wishes to save. It is a stunning achievement, violently personal, gifted, distilled from a lifelong mediation on race, sometimes less intelligent than given to big generalizations and intellectual grandiosity, yet ever a whiplash on the national conscience, if steadily remote in its fury. Baldwin opens with a new essay, "The Price of the Ticket," describing his early days as a reviewer-essayist for highbrow leftist periodicals, then summarizes his feelings about the total racism of current American institutions: "Leaving aside my friends, the people I love, who cannot, usefully, be described as either black or white, they are, like life itself, thank God, many many colors, I do not feel, alas, that my country has any reason for self-congratulation"—a sentence, alas, that is a Baldwinian jumble. His early essays often find him straining for destructive criticism: it is Baldwin, after all, who sees the black in white America and the white in black America so clearly blended that he can tell us there is no white America. One of his best reviews is of Ross Lockridge's celebration of America in the mythic Raintree County. "The book, which had no core to begin with, becomes as amorphous as cotton candy under the drumming flows of words. . .words. . .Mr. Lockridge uses. . .as a kind of shimmering web, hiding everything with an insistent radiance and proving that, after all, everything is, or is going to be, all right. . Raintree County, according to its author, cannot be found on any map: and it is always summer there. He might also have added that no one lives there anymore." Here also are Baldwin's searing introduction of white America to Malcolm X and Harlem's black Muslims (The Fire Next Time) in which he finds black racism as misguided as the white devils it attacks; his shadowboxing with Norman Mailer; his attack on the protest novel, from Uncle Tom's Cabin to Native Son (which angered his friend Richard Wright) and marvelous deflation of, among others, Carmen Jones, Porgy and Bess and The Birth of a Nation for misrepresenting the black experience. Most moving of all is his autobiographical tour of his blackness No Name on the Street: "To be an Afro-American, or an American black, is to be in the situation, intolerably exaggerated, of all those who have never found themselves part of a civilization they could in no wise honorably defend—which they were compelled, indeed, endlessly to attack and condemn—and who yet spoke out of the most passionate love, hoping to make the kingdom new. . .

Pub Date: Oct. 28, 1985

ISBN: 0312643063

Page Count: -

Publisher: St. Martin's

Review Posted Online: Sept. 16, 2011

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Sept. 15, 1985

GENERAL NONFICTION

Share your opinion of this book

More by James Baldwin

BOOK REVIEW

by James Baldwin ; edited by Jennifer DeVere Brody & Nicholas Boggs ; illustrated by Yoran Cazac

by James Baldwin ; edited by Randall Kenan

by James Baldwin

by E.T.A. Hoffmann ‧ RELEASE DATE: Oct. 28, 1996

This is not the Nutcracker sweet, as passed on by Tchaikovsky and Marius Petipa. No, this is the original Hoffmann tale of 1816, in which the froth of Christmas revelry occasionally parts to let the dark underside of childhood fantasies and fears peek through. The boundaries between dream and reality fade, just as Godfather Drosselmeier, the Nutcracker's creator, is seen as alternately sinister and jolly. And Italian artist Roberto Innocenti gives an errily realistic air to Marie's dreams, in richly detailed illustrations touched by a mysterious light. A beautiful version of this classic tale, which will captivate adults and children alike. (Nutcracker; $35.00; Oct. 28, 1996; 136 pp.; 0-15-100227-4)

Pub Date: Oct. 28, 1996

ISBN: 0-15-100227-4

Page Count: 136

Publisher: Harcourt

Review Posted Online: May 19, 2010

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Aug. 15, 1996

More by E.T.A. Hoffmann

by E.T.A. Hoffmann ; adapted by Natalie Andrewson ; illustrated by Natalie Andrewson

by E.T.A. Hoffmann & illustrated by Julie Paschkis

TO THE ONE I LOVE THE BEST

Episodes from the life of lady mendl (elsie de wolfe).

by Ludwig Bemelmans ‧ RELEASE DATE: Feb. 23, 1955

An extravaganza in Bemelmans' inimitable vein, but written almost dead pan, with sly, amusing, sometimes biting undertones, breaking through. For Bemelmans was "the man who came to cocktails". And his hostess was Lady Mendl (Elsie de Wolfe), arbiter of American decorating taste over a generation. Lady Mendl was an incredible person,- self-made in proper American tradition on the one hand, for she had been haunted by the poverty of her childhood, and the years of struggle up from its ugliness,- until she became synonymous with the exotic, exquisite, worshipper at beauty's whrine. Bemelmans draws a portrait in extremes, through apt descriptions, through hilarious anecdote, through surprisingly sympathetic and understanding bits of appreciation. The scene shifts from Hollywood to the home she loved the best in Versailles. One meets in passing a vast roster of famous figures of the international and artistic set. And always one feels Bemelmans, slightly offstage, observing, recording, commenting, illustrated.

Pub Date: Feb. 23, 1955

ISBN: 0670717797

Publisher: Viking

Review Posted Online: Oct. 25, 2011

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Feb. 1, 1955

More by Ludwig Bemelmans

developed by Ludwig Bemelmans ; illustrated by Steven Salerno

by Ludwig Bemelmans ; illustrated by Steven Salerno

by Ludwig Bemelmans

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

The price of the ticket : collected nonfiction, 1948-1985

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

901 Previews

28 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station32.cebu on March 30, 2022

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

The price of the ticket

I n July 1957, an ocean liner set sail from France to New York and on board was the 32-year-old, James Baldwin . Nine years earlier, he had made the reverse journey and left his native New York City for Paris with $40 in his pocket and no knowledge of either France or the French language. He had chosen Paris because his mentor, Richard Wright, was living there, having sought refuge from the demeaning racial politics of his homeland. The young James Baldwin felt that if he was ever going to discover himself as a man and a writer, then he would also have to flee the United States. His exile in France had often been difficult, and was marked by poverty, a period in jail, and at least one suicide attempt, but in the end this opening act of Baldwin's literary life proved to be triumphantly productive. His first novel, Go Tell it on the Mountain (1953) established his name, and his collection of essays, Notes of a Native Son (1955), and his controversial second novel, Giovanni's Room (1956), secured his reputation as an important, and fast-rising literary figure.

Baldwin's first books were written in hotel rooms, in borrowed houses or apartments, and eventually in his own cramped flat in Paris. During these early European years, the relatively unknown Baldwin was largely "offstage" and beyond the scrutiny of media attention. Aside from the weight of his own ambition, and the practical difficulty of money, there was little pressure upon his slender shoulders. The young writer was focused, fearlessly engaging with a wide range of difficult subjects, including the frustrations of adolescence, homosexuality, and the problematics of the father-son relationship.

The literary tone that he seemed to have perfected was a powerful fusion of African-American oration and 19th-century moral romanticism in the tradition of Thoreau and Emerson. Baldwin's gracefully lilting sentences were informed not only by the cadences of the King James Bible, but by Henry James's narratives. The young author's mutable words, and elliptical phrases, endlessly circled back on themselves in a self-questioning manner, weaving patterns of doubt while, paradoxically, achieving an overall effect of carefully attained certitude. Baldwin's decision to return to the US in July 1957 marked a turning point in the writer's career and signalled the end of this age of both innocence and discovery. The man who stood on the deck of the ocean liner in 1957, and who turned his face towards the western horizon, knew that by ending his European apprenticeship and returning to the US he would be stepping onstage and into visibility.

In 1941, the 17-year-old Baldwin had declared, in his high school yearbook, an ambition to be a "novelist-playwright". When asked to add a further comment, Baldwin wrote, "Fame is the spur and - ouch!" All journeys exact a price, but as Baldwin sailed towards the second act of his writing career, there is no way he could have intuited just how difficult for him, physically and emotionally, the next decade or so would prove, and how the frenzy of these years would ultimately affect his stated ambition to be a "novelist-playwright".

The second act of Baldwin's literary life extended from 1957 until 1970, and in this time he produced two novels, Another Country (1962) and Tell Me How Long the Train's Been Gone (1968). The somewhat plotless drama of Another Country eventually holds together because of the passion and intensity of the prose, particularly evident in the bold opening section of the novel, which concerns the jazz musician Rufus Scott. Even here, however, the tone occasionally topples over into rhetorical excess and melodrama, and by the time we reach Tell Me How Long the Train's Been Gone, Baldwin's understanding of form seems to have abandoned him. The narrative is inert and rendered largely in flashback, the tone is often shrill, the characterisation sketchy, and the book insists on pounding us over the head as it makes its "points". In fact, it is difficult to believe that the author of this rambling fiction could be the same person who wrote the poised and understated Go Tell it on the Mountain.

Baldwin's non-fiction of the early 60s was better suited to the more declarative register in his voice. The sinewy, almost hesitant prose, and the unstable syntax suggest a purposeful, intellectual questing, but in his fiction these deviations imply an incompleteness of characterisation and a structural formlessness which gives rise to a suspicion that the author has simply taken both hands off the wheel. His non-fiction better accommodates his stylistic circumlocution, and the essays in Nobody Knows My Name (1961) successfully pick up where Notes of a Native Son left off, so much so that the publisher subtitled them, More Notes of a Native Son.

The Fire Next Time (1963) is undoubtedly Baldwin's masterpiece, and it spectacularly captures the racial and socio-cultural divisions in the US on the eve of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The publication of the book created a sensation, for here was a black man insisting that white Americans might not care about their own salvation, or their moral corruption, but if they don't shape up then they will be faced with potential disaster. All over the south, black people were being beaten at lunch counters, or at voter registration drives, or when peacefully protesting in the street, or worshipping in their churches - but this finger-wagging, pop-eyed, diminutive Negro of reputedly questionable morals was warning white Americans that the same iniquities might well be visited on them unless they began to put their house in order.

His high style embraced ambiguity and paradox at a time when nobody had heard a writer, let alone a black writer, speak of race in a manner that went beyond the crude vulgarities of a discourse rooted in binary oppositions: good/bad, black/white, right/wrong. To Baldwin, the drama of race involved the confession box and whispered narratives of guilt that might eventually give way to blessings of absolution and "no charge" on the penance front. Acute social observation and personal autobiography come together dramatically in The Fire Next Time, and this grand lyrical assault upon his country's wilful myopia, and its inability to confront the full implications of its own history, was published, appropriately enough, 100 years after the emancipation of the slaves.

Much of Baldwin's other writing in this period, including the play Blues for Mr Charlie (1964), the screenplay based on the life and death of Malcolm X (eventually published as One Day When I Was Lost), and numerous uncollected essays, testify to the stylistic shift away from the nuanced ebb and flow of the first act of his literary career, and his new engagement with polemic. This was the age of political assassinations, prison riots at Attica and elsewhere, and the emergence of the Black Power movement; given the times, Baldwin's belief in the refining power of redemptive love was beginning to sound decidedly unhip.

As the 60s progressed, an increasingly vociferous Baldwin appeared keen to adopt a public position in all his writings, as though he were trying to defuse some of the criticism that was being levelled against him, particularly from the African-American community and writers such as Eldridge Cleaver and Amiri Baraka. He seems to have been stung into becoming not just a witness, but a mouthpiece. However, this anxious attempt to "hustle" a politically strident voice felt false - even, one suspects, to Baldwin himself.

This second act of his literary life is remarkable, not only because of the uneven quality of the work, but also because of the degree of fame that Baldwin achieved. In the mid-60s he was arguably the most photographed author in the world; on May 17 1963 he was on the cover of Time magazine the week after John F Kennedy. He was in constant demand for lectures and readings all over the US and around the world, and he was continually being interviewed on television, radio, and in print. His performances were often dazzling and were generally delivered with an authority that overwhelmed the audience.

With this level of fame came a daunting travel schedule, and it is astonishing that Baldwin found the time to get any work done. In fact, he was only able to do so by retreating to the MacDowell Colony in New Hampshire, or to various friends' homes in New England, or else travelling to Turkey and hiding away from the monster called fame. There could be no denying, however, that this was a monster he had chased down and fed, and he was fully aware that it was easier, and more profitable, both financially and in terms of his profile, to stride to the podium, as opposed to the desk. In a July 1965 televised BBC interview with the writer Colin MacInnes, Baldwin spoke openly of his predicament: "The great terror of public speaking is that you begin to listen to yourself. By and by, since you are always telling people what to think, you begin to forget what you do to think. And the moment that happens, of course, it's over. It's over."

By 1970 it was too much, and 46-year-old James Baldwin, his health broken, and in need of rest and recuperation, returned to France, this time to the south, to St Paul de Vence, where he began the third and final act of his literary life. While the work in the second act might not have entirely fulfilled the promise of the first, he had, during his 13 years in America, developed a reputation as a courageous man and a brilliant orator who spoke out for moral change, and he was, indeed, regarded by many as a witness. He was unquestionably famous, but by this stage of his life he was more famous for being a celebrity-spokesman than a writer.

By leaving the relative "obscurity" of Paris, and stepping on to centre stage in the US, he had achieved "fame", but it was now beginning to appear that he had he done so at the cost of his writing. The question facing him now was what to write about? The US in 1970 bore little relationship to the US of 1957, and his role as a witness no longer appeared to be crucial. In 1973, Time magazine decided not to run an exclusive interview with Baldwin and Josephine Baker in France, conducted by their European correspondent, Henry Louis Gates Jnr. They deemed Baldwin - to use their word - "passe". However, though Baldwin's celebrity status was declining, he could at least reapply himself to his writing. Or so he thought.

Even the most trenchant supporter of Baldwin's work will find it difficult to argue that the two novels of the 70s, If Beale Street Could Talk (1972) and Just Above My Head (1978), would, if they were not part of the Baldwin oeuvre, be much spoken of today. They are excessively rhetorical, structurally confusing, and lacking in any coherent characterisation. There are passages in both novels, particularly in Just Above My Head, which soar with a familiar eloquence, but all too often such moments quickly give way to longueurs where one feels as though the impatient author, Baldwin, has decided to elbow his way past the gallery of assembled characters and speak directly to us - witness to congregation.

Again, Baldwin's non-fiction of the 70s and early 80s is more successful than his fiction, because the form itself is more forgiving of his rhetorical habits. However, while No Name in the Street (1972) and The Devil Finds Work (1976) have much of his familiar perception and wit, the sinewy prose appears to have atrophied, and the liturgical rhythms have lost some of their skip and their beat. Sadly, The Evidence of Things Not Seen (1985), Baldwin's report on the Wayne Williams trial for the Atlanta child murders, is a book that appears to have been, from the beginning, badly conceived. As it proceeds it feels increasingly padded with irrelevant autobiographical asides that continually lead the reader away from, rather than towards, the central subject matter.

Baldwin's biographer, James Campbell, recalls talking to him in the early 80s about his "comeback". I, too, remember similar late-night conversations with Jimmy in France. He would speak of the "comeback" with some gravitas, and then crack a huge smile as though the very notion of what he had just said amused him. But a part of him was in earnest. He knew that some of the purpose and clarity that he possessed in his early writing career had been lost in those recklessly public 13 years. When he told me, in the summer of 1984, that he would soon be publishing his collected essays, and that he was going to call them, The Price of the Ticket, he burst out laughing. The Price of the Ticket was a wonderfully compelling title, but I never asked him directly, neither on that night nor on subsequent nights, what the price of the ticket was, or what kind of a journey he had endured, or enjoyed, in return.

It is impossible to know what would have happened to Baldwin's writing career if he had not boarded that ship to New York in July 1957 and sailed towards fame. It may well be that, instead of producing more sensitively nuanced work in the tradition of his first two novels and Notes of a Native Son, his imagination might have stumbled in France (or in Turkey, or in Switzerland). Simply reading about developments back home in the US, as opposed to participating in them, would probably have driven Baldwin to distraction. Between 1957 and 1970, he utilised his great strength of purpose, and his boundless energy, in an attempt to combine his role as a public intellectual and spokesperson with his vocation as a writer. However, as time passed, it became increasingly clear that exposing his private life - the wellspring of his creativity - to public scrutiny, and investing so heavily in his sense of himself as a celebrity-witness, was costing him dearly as a writer.

Baldwin was a fiercely intelligent and perceptive, and he knew the perils of neglecting the inner self and relinquishing so much of his privacy. He frequently claimed that he felt compelled to live such a furiously public life as part of his duty to be a witness, but there are many ways of bearing witness. To do so while exposing oneself to the glare of the media spotlight is a particularly risky way of going about one's obligation. I am sure that, as he mounted public platforms, or once again submitted himself to the often banal questions of the interviewer, he understood that he was avoiding the inner meditation and reflection - the sitting in judgment on oneself - which is an essential part of a writer's development. He seemed to be forever onstage looking out, and part of his inner turmoil was fed by his understanding that the price of the ticket that he had purchased had necessitated his mortgaging his life as a writer.

When I first met Jimmy, in the summer of 1983, in the main village square in St Paul de Vence, the BBC producer who accompanied me asked him if he thought that he would ever win the Nobel prize. I was embarrassed by this question but, as generous as ever, Jimmy laughed, then took a languorous draw from his cigarette, smiled and said, "they'll probably get round to giving it to me some day". But that smile was a knowing smile.

As Baldwin sailed towards his destiny in July 1957, he knew that in the immediate future it would be very difficult for him to "settle down" and enjoy a life of domestic tranquillity. Perhaps if somebody had appeared in act two of his literary career and forced him to change his lifestyle, then Jimmy might have saved some of himself for Jimmy, and ultimately for his work. After all, to fall in love and achieve security is to find a kind of peace - a kind of invisibility. But this person did not appear, and during those 13 years his crazed, peripatetic schedule seemed to ensure that domestic stability, let alone tranquillity, was doomed to remain an impossible dream. Outside of his immediate family, he lacked a constantly close companion who, to put it simply, could be relied upon to love and protect him.

So much of his work rehearses the great difficulty, yet the absolute necessity, of love, and Baldwin was a romantic, and he did crave the type of protective love that would be enduring. As is often the case with generous and gregarious people, his fierce independence and general bonhomie often obscured this deep desire to be looked after and feel safe, but fame introduces a particular desolation into the soul, a loneliness that no amount of partying, or travelling, or drinking can mask.

The day after Baldwin died, I remember standing in the entrance hall to the house in St Paul de Vence and looking at his body as he lay in an open coffin. In the living room, his Swiss friend of nearly 40 years, Lucien Happersberger, his brother David Baldwin, and his friend and secretary, Bernard Hassell, were talking quietly. I sat down next to Jimmy and stared into his now peaceful face. I remembered that I had challenged him one snowy night in Amherst, Massachusetts, and asked him why he was wasting his time in "this dump of a town" instead of buckling down and producing another Jimmy Baldwin novel. The folly and stupidity of youth. He heard me out, then smiled gracefully and said, "One day you'll understand, baby." As I looked at him in his coffin, I wanted to apologise for not understanding that night in Amherst. He had given me friendship and warmth, and in return I had nothing to give back to him.

Twenty years after his death, I still have nothing tangible to give back to him, except some increased understanding of the price that he paid to become the extraordinary man that he was. By returning to the US in 1957, he found what he called a "role", and he found fame, but in order to achieve these goals he had to live a life that in the end could only prove injurious to him as a writer. I now understand that behind the clever title, The Price of the Ticket, there was courage, sorrow and pain. There was no self-pity. I now understand that the 17-year-old boy already knew something profound about the man that he would become. The boy had already intuited the price of the ticket. "Fame is the spur and - ouch!" As the talented youngster grew into the eminent man, he remained true to his dream, and he succeeded beyond anybody's wildest hopes, including his own; but every day he wrestled hard with the frustration of knowing exactly what he had lost, and missed out on, as he made his determined, and wilful, way in the world.

In November 1987 in St Paul de Vence, an ailing and bedridden Jimmy turned to David Leeming, another of his biographers, and said: "Sometimes I can't believe that I'm famous too." At this stage of his life, Jimmy's mind was beginning to wander, and his body was weakening. However, he was simply checking that he had really made, and completed, the journey towards fame. He knew that he had paid the price. He had been suffering the heartache of rejections from publishers, indifferent reviews, and falling sales for years now, but he had borne these slights with dignity. He may not have had at his side the one loyal, loving person that he seemed to yearn for, but at this juncture of his life he was surrounded by Lucien, David and Bernard, all of whom were devoted to him and who loved him deeply. And the passion and purpose of his writing, his early work in particular, had long ago ensured the permanence of his place in the literary canon. And, of course, more than any other mid- 20th-century American writer, he had set the stage for the debate on race that was needed then, and is still desperately needed today. The journey was complete. The price paid. The pain and frustration fully absorbed. "Sometimes I just can't believe that I'm famous too." Three days later, James Baldwin died.

· Foreigners: Three English Lives by Caryl Phillips will be published by Harvill Secker in September.

- James Baldwin

Most viewed

- ~ Overview ~

- Synopsis

- Director's Statement

- On-Camera Witnesses

- Orig Funders

- Producing Partners

- Credits

- Festivals & Awards

- Film Screenings & Broadcasts

- Photo Gallery

- Restoration

- ~ Overview ~

- 16mm Preservation

- Digital Conversion

- JB 90th Birthday

- PBS Broadcasts

- PBS Learning Media™

- French (1998)

- English (2015)

- Spanish (TBD)

- HD Screenings & Events

- ~ Overview ~

- Past Events

- Timeline

- Biography

- Bibliography

- Topics & Themes

- Civil Rights

- Resources

- ~ M i s s i o n ~

- Scholars & Advisors

- JB Centennial Funders +

- Production Co.

- Board Members

- Distributor

- Contact Info

- Non-Profit Partner

JAMES ARTHUR BALDWIN

-- biographical timeline --.

- MEMBERSHIPS:

- -- Congress of Racial Equality.

- -- National Committee for Sane Nuclear Policy.

- -- Actor's Studio.

- -- National Institute of Arts and Letters.

. . . . . . .

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Price of the Ticket is an anthology collecting nonfiction essays by James Baldwin.Spanning the years 1948 to 1985, the essays offer Baldwin's reflections on race in America.. The title was repurposed for the 1989 documentary film James Baldwin: The Price of the Ticket, directed by Karen Thorsen.

The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction 1948-1985. by James Baldwin. St. Martin's. 704 pp. $29.95. "The failure of the protest novel," James Baldwin wrote in 1949, "lies in its rejection of life, the human being, the denial of his beauty, dread, power, in its insistence that it is his categorization alone which is real and which ...

The Price of the Ticket collects much of the best work of one of our finest living writers."—Sam Cornish, The Christian Science Monitor "James Baldwin's essays on race in America are enlightening, entertaining and, because of his remarkable prescience, a bit eerie . . . In these 51 pieces all of which appeared in magazines or previous ...

In a 1962 essay titled "The Creative Process," found in the altogether fantastic anthology The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction (public library), Baldwin lays out a manifesto of sorts, nuanced and dimensional yet exploding with clarity of conviction, for the trying but vital responsibility that artists, "a breed of men and women ...

It is most evident in The Price of a Ticket, a collection of Baldwin's most powerful essays exploring the social interaction of ... It was through the 1989 documentary, James Baldwin: The Price of a Ticket, that we are able truly see Baldwin for who he was, and what he stood for. Through the intimate interviews on behalf of family members ...

Baldwin opens with a new essay, "The Price of the Ticket," describing his early days as a reviewer-essayist for highbrow leftist periodicals, then summarizes his feelings about the total racism of current American institutions: "Leaving aside my friends, the people I love, who cannot, usefully, be described as either black or white, they are ...

The Price of the Ticket. Photography credit: Carl Van Vechten. Back in 1985, on the morning of November 23 (a cold, wet, gray autumn Saturday), I woke up happy. At that time in my life, nothing could have been more unusual. But I knew that before that day's sun had set, I was going to meet James Baldwin, whose body of work (the novels and ...

''The Price of the Ticket'' is an intriguing collection of James Baldwin's articles, essays, and commentaries on race in America. The essays cover his writings from 1948 - 1985.

The Price of the Ticket is an anthology collecting nonfiction essays by James Baldwin. Spanning the years 1948 to 1985, the essays offer Baldwin's reflections on race in America.

The Price of the Ticket. : An essential compendium of James Baldwin's most powerful nonfiction work, calling on us "to end the racial nightmare, and achieve our country.". Personal and prophetic, these essays uncover what it means to live in a racist American society with insights that feel as fresh today as they did over the 4 decades in ...

The works of James Baldwin constitute one of the major contributions to American literature in the twentieth century, and nowhere is this more evident than in The Price of the Ticket, a compendium of nearly fifty years of Baldwin's powerful nonfiction writing. With truth and insight, these personal, prophetic works speak to the heart of the experience of race and identity in the United States.

The price of the ticket : collected nonfiction, 1948-1985 Bookreader Item Preview ... Baldwin, James, 1924-1987. Publication date 1985 Publisher New York : St. Martin's/Marek Collection inlibrary; printdisabled; internetarchivebooks Contributor Internet Archive Language English.

The price of the ticket. In 1953, James Baldwin, a hard-up writer in Paris, published the extraordinary novel Go Tell it on the Mountain. Four years later he sailed home to the United States to ...

James Baldwin. 4.68. 614 ratings60 reviews. The works of James Baldwin constitute one of the major contributions to American literature in the twentieth century, and nowhere is this more evident than in The Price of the Ticket, a compendium of nearly fifty years of Baldwin's powerful nonfiction writing. With truth and insight, these personal ...

In numerous essays, novels, plays and public speeches, the eloquent voice of James Baldwin spoke of the pain and struggle of black Americans and the saving power of brotherhood. James Baldwin was born in Harlem in 1924. The oldest of nine children, he grew up in poverty, developing a troubled relationship with his strict, religious stepfather.

The Price Of The Ticket: Collected Non-Fiction; St. Martin's/ Marek; essays. 2004: Native Sons; Random House/One World; a memoir by Sol Stein; with letters, a short story and a play by James Baldwin. 2011: The Cross of Redemption: Uncollected Writings; Vintage; editor, Randall Garrett Kenan; essays. Works Performed and / or Televised:

motion picture | Made-for-TV programme or made-for-video/DVD release. Feature film (over 60 minutes). "Sometimes I feel like a motherless child" (trad.) arr Odetta; "Why do I lie to myself about you" performed by Fats Waller; "Blues walk" by Lou Donaldson, performed by James Moody; "Naima" by and performed by John Coltrane; "Mournful serenade" by Jelly Roll Morton; "In a sentimental mood" by ...

Died in St. Paul-de-Vence, France, December 1st, 1987. "You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world. But then you read. It was books that taught me..." ~ from the film, James Baldwin: The Price of the Ticket. "There is not another writer who expresses with such poignancy and abrasiveness the dark ...

The Story Of James Baldwin: The Price Of The Ticket. The story of James Baldwin- The Price of the Ticket is by a documentary is Karen Thorsen writer in the mid-twentieth century. James Baldwin who was black and homosexual. From a social point of view, he had at least the two challenges of being black and homosexual from which he might be ...

Building on the Classic Film Biography "JAMES BALDWIN: THE PRICE OF THE TICKET" Top. JAMES ARTHUR BALDWIN-- Biographical Timeline --1924: Born August 2nd in New York's Harlem Hospital. ... First essay published in Partisan Review: "Everybody's Protest Novel." 1952: Finished writing first novel, GO TELL IT ON THE MOUNTAIN, in Loèche-les-Bains ...