Better Business Through Better Writing

Jean is President of Leadership On Paper® and a Founding Partner of The Right Direction. Leadership On Paper® is a consultative service founded in 1986. Its mission is to help business and technical people extend their leadership and management skills to written communication. The firm provides training and also works with senior management at corporations to improve the quality of internal communication.

The Right Direction, a newer venture, is also a consulting firm. It offers a range of services to business with a focus on problem solving, creativity and group decision-making. Clients include Procter & Gamble, Walt Disney, Clorox, Nestle, Google, Abbott Labs, Walmart, Intuit, Mars, Sun Products, ConAgra, Coors, Kroger, McCormick, Centene, Kimberly-Clark,The Royal Bank of Canada and The Cleveland Indians.

Jean's skills come from years of hands-on experience as an Executive Vice President of Dancer Fitzgerald Sample (now Saatchi & Saatchi), a large multi-national advertising agency. At DFS, Jean ran major accounts, including Procter & Gamble. He introduced successful brands like Luvs Disposable Diapers and developed programs to reposition existing brands. One such program took Duracell from a small specialty brand to the #1 premium battery in the world. In addition to his other responsibilities, Mr. Plumez was a member of the DFS Board of Directors. After 18 years with DFS, Mr. Plumez left to form Leadership on Paper®.

Jean started his career as a commissioned officer assigned to U.S. Army Intelligence. He then worked for two years as a chemical engineer for Mobil Oil before getting his MBA from The Wharton School.

Jean Paul Plumez

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

Leadership →

- 26 Mar 2024

- Cold Call Podcast

How Do Great Leaders Overcome Adversity?

In the spring of 2021, Raymond Jefferson (MBA 2000) applied for a job in President Joseph Biden’s administration. Ten years earlier, false allegations were used to force him to resign from his prior US government position as assistant secretary of labor for veterans’ employment and training in the Department of Labor. Two employees had accused him of ethical violations in hiring and procurement decisions, including pressuring subordinates into extending contracts to his alleged personal associates. The Deputy Secretary of Labor gave Jefferson four hours to resign or be terminated. Jefferson filed a federal lawsuit against the US government to clear his name, which he pursued for eight years at the expense of his entire life savings. Why, after such a traumatic and debilitating experience, would Jefferson want to pursue a career in government again? Harvard Business School Senior Lecturer Anthony Mayo explores Jefferson’s personal and professional journey from upstate New York to West Point to the Obama administration, how he faced adversity at several junctures in his life, and how resilience and vulnerability shaped his leadership style in the case, "Raymond Jefferson: Trial by Fire."

- 24 Jan 2024

Why Boeing’s Problems with the 737 MAX Began More Than 25 Years Ago

Aggressive cost cutting and rocky leadership changes have eroded the culture at Boeing, a company once admired for its engineering rigor, says Bill George. What will it take to repair the reputational damage wrought by years of crises involving its 737 MAX?

- 02 Jan 2024

- What Do You Think?

Do Boomerang CEOs Get a Bad Rap?

Several companies have brought back formerly successful CEOs in hopes of breathing new life into their organizations—with mixed results. But are we even measuring the boomerang CEOs' performance properly? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- Research & Ideas

10 Trends to Watch in 2024

Employees may seek new approaches to balance, even as leaders consider whether to bring more teams back to offices or make hybrid work even more flexible. These are just a few trends that Harvard Business School faculty members will be following during a year when staffing, climate, and inclusion will likely remain top of mind.

- 12 Dec 2023

Can Sustainability Drive Innovation at Ferrari?

When Ferrari, the Italian luxury sports car manufacturer, committed to achieving carbon neutrality and to electrifying a large part of its car fleet, investors and employees applauded the new strategy. But among the company’s suppliers, the reaction was mixed. Many were nervous about how this shift would affect their bottom lines. Professor Raffaella Sadun and Ferrari CEO Benedetto Vigna discuss how Ferrari collaborated with suppliers to work toward achieving the company’s goal. They also explore how sustainability can be a catalyst for innovation in the case, “Ferrari: Shifting to Carbon Neutrality.” This episode was recorded live December 4, 2023 in front of a remote studio audience in the Live Online Classroom at Harvard Business School.

- 05 Dec 2023

Lessons in Decision-Making: Confident People Aren't Always Correct (Except When They Are)

A study of 70,000 decisions by Thomas Graeber and Benjamin Enke finds that self-assurance doesn't necessarily reflect skill. Shrewd decision-making often comes down to how well a person understands the limits of their knowledge. How can managers identify and elevate their best decision-makers?

- 21 Nov 2023

The Beauty Industry: Products for a Healthy Glow or a Compact for Harm?

Many cosmetics and skincare companies present an image of social consciousness and transformative potential, while profiting from insecurity and excluding broad swaths of people. Geoffrey Jones examines the unsightly reality of the beauty industry.

- 14 Nov 2023

Do We Underestimate the Importance of Generosity in Leadership?

Management experts applaud leaders who are, among other things, determined, humble, and frugal, but rarely consider whether they are generous. However, executives who share their time, talent, and ideas often give rise to legendary organizations. Does generosity merit further consideration? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 24 Oct 2023

From P.T. Barnum to Mary Kay: Lessons From 5 Leaders Who Changed the World

What do Steve Jobs and Sarah Breedlove have in common? Through a series of case studies, Robert Simons explores the unique qualities of visionary leaders and what today's managers can learn from their journeys.

- 06 Oct 2023

Yes, You Can Radically Change Your Organization in One Week

Skip the committees and the multi-year roadmap. With the right conditions, leaders can confront even complex organizational problems in one week. Frances Frei and Anne Morriss explain how in their book Move Fast and Fix Things.

- 26 Sep 2023

The PGA Tour and LIV Golf Merger: Competition vs. Cooperation

On June 9, 2022, the first LIV Golf event teed off outside of London. The new tour offered players larger prizes, more flexibility, and ambitions to attract new fans to the sport. Immediately following the official start of that tournament, the PGA Tour announced that all 17 PGA Tour players participating in the LIV Golf event were suspended and ineligible to compete in PGA Tour events. Tensions between the two golf entities continued to rise, as more players “defected” to LIV. Eventually LIV Golf filed an antitrust lawsuit accusing the PGA Tour of anticompetitive practices, and the Department of Justice launched an investigation. Then, in a dramatic turn of events, LIV Golf and the PGA Tour announced that they were merging. Harvard Business School assistant professor Alexander MacKay discusses the competitive, antitrust, and regulatory issues at stake and whether or not the PGA Tour took the right actions in response to LIV Golf’s entry in his case, “LIV Golf.”

- 01 Aug 2023

As Leaders, Why Do We Continue to Reward A, While Hoping for B?

Companies often encourage the bad behavior that executives publicly rebuke—usually in pursuit of short-term performance. What keeps leaders from truly aligning incentives and goals? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 05 Jul 2023

What Kind of Leader Are You? How Three Action Orientations Can Help You Meet the Moment

Executives who confront new challenges with old formulas often fail. The best leaders tailor their approach, recalibrating their "action orientation" to address the problem at hand, says Ryan Raffaelli. He details three action orientations and how leaders can harness them.

How Are Middle Managers Falling Down Most Often on Employee Inclusion?

Companies are struggling to retain employees from underrepresented groups, many of whom don't feel heard in the workplace. What do managers need to do to build truly inclusive teams? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 14 Jun 2023

Every Company Should Have These Leaders—or Develop Them if They Don't

Companies need T-shaped leaders, those who can share knowledge across the organization while focusing on their business units, but they should be a mix of visionaries and tacticians. Hise Gibson breaks down the nuances of each leader and how companies can cultivate this talent among their ranks.

Four Steps to Building the Psychological Safety That High-Performing Teams Need

Struggling to spark strategic risk-taking and creative thinking? In the post-pandemic workplace, teams need psychological safety more than ever, and a new analysis by Amy Edmondson highlights the best ways to nurture it.

- 31 May 2023

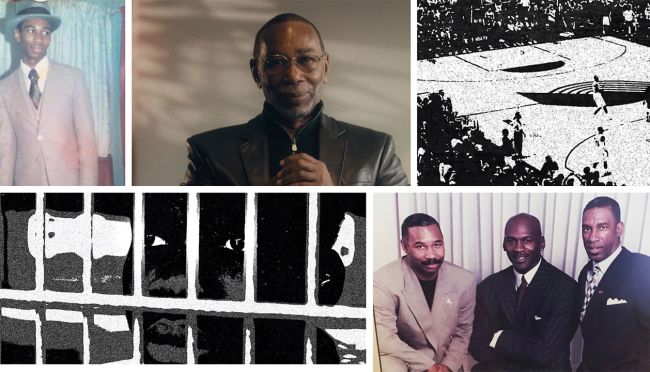

From Prison Cell to Nike’s C-Suite: The Journey of Larry Miller

VIDEO: Before leading one of the world’s largest brands, Nike executive Larry Miller served time in prison for murder. In this interview, Miller shares how education helped him escape a life of crime and why employers should give the formerly incarcerated a second chance. Inspired by a Harvard Business School case study.

- 23 May 2023

The Entrepreneurial Journey of China’s First Private Mental Health Hospital

The city of Wenzhou in southeastern China is home to the country’s largest privately owned mental health hospital group, the Wenzhou Kangning Hospital Co, Ltd. It’s an example of the extraordinary entrepreneurship happening in China’s healthcare space. But after its successful initial public offering (IPO), how will the hospital grow in the future? Harvard Professor of China Studies William C. Kirby highlights the challenges of China’s mental health sector and the means company founder Guan Weili employed to address them in his case, Wenzhou Kangning Hospital: Changing Mental Healthcare in China.

- 09 May 2023

Can Robin Williams’ Son Help Other Families Heal Addiction and Depression?

Zak Pym Williams, son of comedian and actor Robin Williams, had seen how mental health challenges, such as addiction and depression, had affected past generations of his family. Williams was diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a young adult and he wanted to break the cycle for his children. Although his children were still quite young, he began considering proactive strategies that could help his family’s mental health, and he wanted to share that knowledge with other families. But how can Williams help people actually take advantage of those mental health strategies and services? Professor Lauren Cohen discusses his case, “Weapons of Self Destruction: Zak Pym Williams and the Cultivation of Mental Wellness.”

- 11 Apr 2023

The First 90 Hours: What New CEOs Should—and Shouldn't—Do to Set the Right Tone

New leaders no longer have the luxury of a 90-day listening tour to get to know an organization, says John Quelch. He offers seven steps to prepare CEOs for a successful start, and three missteps to avoid.

What is leadership?

All leaders, to a certain degree, do the same thing. Whether you’re talking about an executive, manager, sports coach, or schoolteacher, leadership is about guiding and impacting outcomes, enabling groups of people to work together to accomplish what they couldn’t do working individually. In this sense, leadership is something you do, not something you are. Some people in formal leadership positions are poor leaders, and many people exercising leadership have no formal authority. It is their actions, not their words, that inspire trust and energy.

Get to know and directly engage with senior McKinsey experts on leadership

Aaron De Smet is a senior partner in McKinsey’s New Jersey office, Carolyn Dewar is a senior partner in the Bay Area office, Scott Keller is a senior partner in the Southern California office, and Vik Malhotra and Ramesh Srinivasan are senior partners in the New York office.

What’s more, leadership is not something people are born with—it is a skill you can learn. At the core are mindsets, which are expressed through observable behaviors , which then lead to measurable outcomes. Is a leader communicating effectively or engaging others by being a good listener? Focusing on behaviors lets us be more objective when assessing leadership effectiveness. The key to unlocking shifts in behavior is focusing on mindsets, becoming more conscious about our thoughts and beliefs, and showing up with integrity as our full authentic selves.

There are many contexts and ways in which leadership is exercised. But, according to McKinsey analysis of academic literature as well as a survey of nearly 200,000 people in 81 organizations all over the world, there are four types of behavior that account for 89 percent of leadership effectiveness :

- being supportive

- operating with a strong results orientation

- seeking different perspectives

- solving problems effectively

Effective leaders know that what works in one situation will not necessarily work every time. Leadership strategies must reflect each organization’s context and stage of evolution. One important lens is organizational health, a holistic set of factors that enable organizations to grow and succeed over time. A situational approach enables leaders to focus on the behaviors that are most relevant as an organization becomes healthier.

Senior leaders must develop a broad range of skills to guide organizations. Ten timeless topics are important for leading nearly any organization, from attracting and retaining talent to making culture a competitive advantage. A 2017 McKinsey book, Leading Organizations: Ten Timeless Truths (Bloomsbury, 2017), goes deep on each aspect.

How is leadership evolving?

In the past, leadership was called “management,” with an emphasis on providing technical expertise and direction. The context was the traditional industrial economy command-and-control organization, where leaders focused exclusively on maximizing value for shareholders. In these organizations, leaders had three roles: planners (who develop strategy, then translate that strategy into concrete steps), directors (who assign responsibilities), or controllers (who ensure people do what they’ve been assigned and plans are adhered to).

What are the limits of traditional management styles?

Traditional management was revolutionary in its day and enormously effective in building large-scale global enterprises that have materially improved lives over the past 200 years. However, with the advent of the 21st century, this approach is reaching its limits.

For one thing, this approach doesn’t guarantee happy or loyal managers or workers. Indeed, a large portion of American workers—56 percent— claim their boss is mildly or highly toxic , while 75 percent say dealing with their manager is the most stressful part of their workday.

For 21st-century organizations operating in today’s complex business environment, a fundamentally new and more effective approach to leadership is emerging. Leaders today are beginning to focus on building agile, human-centered, and digitally enabled organizations able to thrive in today’s unprecedented environment and meet the needs of a broader range of stakeholders (customers, employees, suppliers, and communities, in addition to investors).

What is the emerging new approach to leadership?

This new approach to leadership is sometimes described as “ servant leadership .” While there has been some criticism of the nomenclature, the idea itself is simple: rather than being a manager directing and controlling people, a more effective approach is for leaders to be in service of the people they lead. The focus is on how leaders can make the lives of their team members easier—physically, cognitively, and emotionally. Research suggests this mentality can enhance both team performance and satisfaction.

In this new approach, leaders practice empathy, compassion, vulnerability, gratitude, self-awareness, and self-care. They provide appreciation and support, creating psychological safety so their employees are able to collaborate, innovate, and raise issues as appropriate. This includes celebrating achieving the small steps on the way to reaching big goals and enhancing people’s well-being through better human connections. These conditions have been shown to allow for a team’s best performance.

More broadly, developing this new approach to leadership can be expressed as making five key shifts that include, build on, and extend beyond traditional approaches:

- beyond executive to visionary, shaping a clear purpose that resonates with and generates holistic impact for all stakeholders

- beyond planner to architect, reimagining industries and innovating business systems that are able to create new levels of value

- beyond director to catalyst, engaging people to collaborate in open, empowered networks

- beyond controller to coach, enabling the organization to constantly evolve through rapid learning, and enabling colleagues to build new mindsets, knowledge, and skills

- beyond boss to human, showing up as one’s whole, authentic self

Together, these shifts can help a leader expand their repertoire and create a new level of value for an organization’s stakeholders. The last shift is the most important, as it is based on developing a new level of consciousness and awareness of our inner state. Leaders who look inward and take a journey of genuine self-discovery make profound shifts in themselves and their lives; this means they are better able to benefit their organization. That involves developing “profile awareness” (a combination of a person’s habits of thought, emotions, hopes, and behavior in different circumstances) and “state awareness” (the recognition of what’s driving a person to take action). Combining individual, inward-looking work with outward-facing actions can help create lasting change.

Introducing McKinsey Explainers : Direct answers to complex questions

Leaders must learn to make these five shifts at three levels : transforming and evolving personal mindsets and behaviors; transforming teams to work in new ways; and transforming the broader organization by building new levels of agility, human-centeredness, and value creation into the entire enterprise’s design and culture.

An example from the COVID-19 era offers a useful illustration of this new approach to leadership. In pursuit of a vaccine breakthrough, at the start of the pandemic Moderna CEO Stéphane Bancel increased the frequency of executive meetings from once a month to twice a week. The company implemented a decentralized model enabling teams to work independently and deliver on the bold goal of providing 100 million doses of vaccines in 12 months. “The pace was unprecedented,” Bancel said.

What is the impact of this new approach to leadership?

This new approach to leadership is far more effective. While the dynamics are complex, countless studies show empirical links among effective leadership, employee satisfaction, customer loyalty, and profitability.

How can leaders empower employees?

Empowering employees , surprisingly enough, might mean taking a more hands-on leadership approach. Organizations whose leaders successfully empower others through coaching are nearly four times more likely to make swift, good decisions and outperform other companies . But this type of coaching isn’t always natural for those with a more controlling or autocratic style.

Here are five tips to get started if you’re a leader looking to empower others:

- Provide clear rules, for example, by providing guardrails for what success looks like and communicating who makes which decisions. Clarity and boundary structures like role remits and responsibilities help to contain any anxiety associated with work and help teams stay focused on their primary tasks.

- Establish clear roles, say, by assigning one person the authority to make certain decisions.

- Avoid being a complicit manager—for instance, if you’ve delegated a decision to a team, don’t step in and solve the problem for them.

- Address culture and skills, for instance, by helping employees learn how to have difficult conversations.

- Begin soliciting personal feedback from others, at all levels of your organization, on how you are experienced as a leader.

How can leaders communicate effectively?

Good, clear communication is a leadership hallmark. Fundamental tools of effective communication include:

- defining and pointing to long-term goals

- listening to and understanding stakeholders

- creating openings for dialogue

- communicating proactively

And in times of uncertainty, these things are important for crisis communicators :

- give people what they need, when they need it

- communicate clearly, simply, and frequently

- choose candor over charisma

- revitalize a spirit of resilience

- distill meaning from chaos

- support people, teams, and organizations to build the capability for self-sufficiency

Learn more about our People & Organizational Performance Practice .

Is leadership different in a hybrid workplace?

A leader’s role may look slightly different in remote or hybrid workplace settings . Rather than walking around a physical site, these leaders might instead model what hybrid looks like, or orchestrate work based on tasks, interactions, or purpose. Being communicative and radiating positivity can go a long way. Leaders need to find other ways to be present and accessible, for example, via virtual drop-in sessions, regular company podcasts, or virtual townhalls. Leaders in these settings may also need to find new ways to get authentic feedback. These tactics can include pulse surveys or learning to ask thoughtful follow-up questions that reveal useful management insights.

Additional considerations, such as making sure that in-person work and togetherness has a purpose, are important. Keeping an eye on inclusivity in hybrid work is also crucial. Listening to what employees want, with an eye to their lived experience, will be vital to leaders in these settings. And a focus on output, outcomes, results, and impact—rather than arbitrary norms about time spent in offices— may be a necessary adaptation in the hybrid era .

How should CEOs lead in this new world?

Just as for leadership more broadly, today’s environment requires CEOs to lead very differently. Recent research indicates that one-third to one-half of new CEOs fail within 18 months.

What helps top performers thrive today? To find out, McKinsey led a research effort to identify the CEOs who achieved breakaway success. We examined 20 years’ worth of data on 7,800 CEOs—from 3,500 public companies across 70 countries and 24 industries. The result is the McKinsey book CEO Excellence: The Six Mindsets That Distinguish the Best Leaders from the Rest (Scribner, March 2022). Watch an interview with the authors for more on what separates the best CEOs from the rest .

Getting perspective on leadership from CEOs themselves is enlightening—and illustrates the nuanced ways in which the new approach to leadership described above can be implemented in practice. Here are a few quotes drawn from McKinsey’s interviews with these top-level leaders :

- “I think the fundamental role of a leader is to look for ways to shape the decades ahead, not just react to the present, and to help others accept the discomfort of disruptions to the status quo.” — Indra Nooyi , former chairman and CEO of PepsiCo

- “The single most important thing I have to do as CEO is ensure that our brand continues to be relevant.” — Chris Kempczinski , CEO of McDonald’s

- “Leaders of other enterprises often define themselves as captains of the ship, but I think I’m more the ship’s architect or designer. That’s different from a captain’s role, in which the route is often fixed and the destination defined.” — Zhang Ruimin , CEO of Haier

- “I think my leadership style [can be called] ‘collaborative command.’ You bring different opinions into the room, you allow for a really great debate, but you understand that, at the end of the day, a decision has to be made quickly.” — Adena Friedman , CEO of Nasdaq

- “We need an urgent refoundation of business and capitalism around purpose and humanity. To find new ways for all of us to lead so that we can create a better future, a more sustainable future.” — Hubert Joly , former chairman and CEO of Best Buy

What is leadership development?

Leaders aren’t born; they learn to lead over time. Neuroplasticity refers to the power of the brain to form new pathways and connections through exposure to novel, unfamiliar experiences. This allows adults to adapt, grow, and learn new practices throughout our lifetimes.

When it comes to leadership within organizations, this is often referred to as leadership development. Programs, books, and courses on leadership development abound, but results vary.

Leadership development efforts fail for a variety of reasons. Some overlook context; in those cases, asking a simple question (something like “What, precisely, is this program for?”) can help. Others separate reflections on leadership from real work, or they shortchange the role of adjusting leaders’ mindsets, feelings, assumptions, and beliefs, or they fail to measure results.

So what’s needed for successful leadership development? Generally, developing leaders is about creating contexts where there is sufficient psychological safety in combination with enough novelty and unfamiliarity to cultivate new leadership practices in response to stimuli. Leadership programs that successfully cultivate leaders are also built around “placescapes”—these are novel experiences, like exploring wilderness trails, practicing performing arts, or writing poetry.

When crafting a leadership development program, there are six ingredients to incorporate that lead to true organizational impact:

- Set up for success:

- Focus your leadership transformation on driving strategic objectives and initiatives.

- Commit the people and resources needed.

- Be clear about focus:

- Engage a critical mass of leaders to reach a tipping point for sustained impact.

- Zero in on the leadership shifts that drive the greatest value.

- Execute well:

- Architect experiential journeys to maximize shifts in mindsets, capabilities, and practices.

- Measure for holistic impact.

A well-designed and executed leadership development program can help organizations build leaders’ capabilities broadly, at scale. And these programs can be built around coaching, mentoring, and having people try to solve challenging problems—learning skills by applying them in real time to real work.

What are mentorship, sponsorship, and apprenticeship?

Mentorship, sponsorship, and apprenticeship can also be part of leadership development efforts. What are they? Mentorship refers to trusted counselors offering guidance and support on various professional issues, such as career progression. Sponsorship is used to describe senior leaders who create opportunities to help junior colleagues succeed. These roles are typically held by more senior colleagues, whereas apprenticeship could be more distributed. Apprenticeship describes the way any colleague with domain expertise might teach others, model behaviors, or transfer skills. These approaches can be useful not only for developing leaders but also for helping your company upskill or reskill employees quickly and at scale.

For more in-depth exploration of these topics, see McKinsey’s insights on People & Organizational Performance . Learn more about McKinsey’s Leadership & Management work—and check out job opportunities if you’re interested in working at McKinsey.

Articles referenced include:

- “ Author Talks: What separates the best CEOs from the rest? ,” December 15, 2021, Carolyn Dewar , Scott Keller , and Vik Malhotra

- “ From the great attrition to the great adaptation ,” November 3, 2021, Aaron De Smet and Bill Schaninger

- “ The boss factor: Making the world a better place through workplace relationships ,” September 22, 2020, Tera Allas and Bill Schaninger

- " Leading agile transformation: The new capabilities leaders need to build 21st century organizations ," October 1, 2018, Aaron De Smet , Michael Lurie , and Andrew St. George

- " Leading Organizations: Ten Timeless Truths ," 2017, Scott Keller and Mary Meaney

- “ Leadership in context ,” January 1, 2016, Michael Bazigos, Chris Gagnon, and Bill Schaninger

- “ Decoding leadership: What really matters ,” January 1, 2015, Claudio Feser, Fernanda Mayol, and Ramesh Srinivasan

Want to know more about leadership?

Related articles.

Reimagining HR: Insights from people leaders

What is leadership: Moving beyond the C-Suite

CEO Excellence

Leadership transparency alone doesn’t guarantee employees will speak up in the workplace

Assistant Professor, HR Management & Organizational Behaviour, Toronto Metropolitan University

Professor of Leadership Development, Rotterdam School of Management

Associate Professor of Management and Organisation Studies, Simon Fraser University

Disclosure statement

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Toronto Metropolitan University provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation CA.

Simon Fraser University provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA.

Simon Fraser University and Toronto Metropolitan University provide funding as members of The Conversation CA-FR.

View all partners

Leaders are often encouraged to be open, authentic and vulnerable at work. Employees are similarly told their voices matter in the workplace and to speak up when they need to. But, being open and honest at work is not always as straightforward as these messages suggest.

What these invitations for honesty don’t fully acknowledge is that speaking up is an act of confidence, bolstered by a steady reserve of self-worth. For many people, speaking one’s truth or revealing one’s honest thoughts and feelings can be a nerve-wracking experience because it leaves them exposed to judgment, ridicule and rejection.

At work, disclosing dissenting opinions, reporting errors or disclosing information about one’s state of mental health can even lead to repercussions. Unsurprisingly, studies consistently show that 50 per cent of employees prefer to keep quiet at work . With this in mind, we set out to examine when and for whom transparent leadership can be beneficial.

Investigating leadership

In our recent research paper , we investigated whether leaders can encourage their employees to express their opinions by demonstrating open and direct communication themselves.

In two studies involving 484 leaders and almost 3,000 of their employees from organizations in Belgium, we examined whether leaders who communicated more transparently created an environment where employees felt comfortable voicing their opinions.

Surveys were sent to leaders and employees over two time periods. The first time, employees completed measures on their leader’s transparency, their own levels of self-esteem based on others’ approval and psychological safety. A month later, they completed a second survey on voice behaviour.

Our studies yielded two key insights. The first is that leaders can set an example. Leaders with a transparent communication style were able to create a climate of psychological safety in their teams. Because followers felt safe to be vulnerable, they were more likely to voice their opinion.

The second is that follower’s self-esteem matters. Transparent leaders were only able to make followers feel safe if the follower had secure self-esteem. Self-esteem can be based on external factors , like the approval of others, or on internal factors , like the extent to which an individual loves and accepts themselves.

Followers who based their self-worth on the approval of others did not feel safe when their leader used direct and open communication and hence, did not open up.

Encouraging vulnerability at work

To help employees to speak up at work, our research suggests that organizations consider several factors. First, organizations should prioritize increasing psychological safety.

Psychological safety refers to the extent to which employees feel like they can voice their concerns or deliver negative feedback at work. When leaders communicate transparently with their employees, their behaviour demonstrates that honesty is valued and that it’s safe for employees to be open in return.

Second, it’s important for organizations to consider their audience when communicating. Direct communication does not make everyone open up. When people base their self-worth on the approval of others, speaking up can be terrifying and keeping quiet or saying the “right” thing, instead of one’s honest opinions, may be the preferred route as it helps protect their self-worth.

Encouraging employees to be aware of the source of their self-esteem and offering mindfulness or self-compassion training could help shift their sense of self-worth. Improving self-compassion , for example, can help people be more accepting and kind to themselves.

Lastly, establishing group norms that promote speaking up is essential. As social beings, humans constantly look to the outside world for cues on how to behave, what is appropriate and what behaviours are safe and acceptable. The more socially acceptable speaking up becomes, the more likely the quality of the conversation will deepen to include richer topics that might otherwise not get broached.

Identifying key team members that are respected and influential and encouraging them to express themselves may help turn the tide so that all team members follow suit.

Fostering trust in the workplace

Our research results suggest that leaders who communicate transparently can encourage their followers to voice their opinions. But the relationship between leadership transparency and follower responsiveness is more nuanced than that.

While transparency can promote open communication, it’s crucial for leaders to recognize that individual reactions vary. Our findings demonstrate that not all followers will find comfort in the presence of managerial candour. Employees who base their self-worth on the approval of others do not feel safe when their leader communicates in a direct manner.

This insight is particularly relevant, given young adults are developing their self-esteem in a backdrop of social networking sites where external validation is the main currency. This is so much so that the next wave of employees has been called “ generation validation .”

We recommend leaders keep their audience in mind when delivering honest messages and suggest they make an effort to gauge whether the recipient is likely to feel confident enough to express their opinion openly. If their goal is to receive direct communication in return, leaders can empower employees to voice their opinions not only by fostering an environment of trust and safety, but also by encouraging their followers to love and accept themselves.

- Transparency

- vulnerability

- Business leadership

- Psychological safety

- Business leaders

- Workplace teams

Events Officer

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

Explore our latest thinking on leadership development and learning strategies

We offer the leadership development resources you need to help leaders at all levels succeed in an ever-changing business environment. Our learning content, strategy, and design experts share our point-of-view, research, and best practices via blog posts, research reports, idea briefs, podcasts, infographics, and leadership papers that help answer your big questions and spark new ideas around developing leaders that are future-ready.

The Changing Face of Leadership Development

In today’s fast-paced world of technology and ever-changing business environments, organizations are urgently seeking better ways to develop their future leaders. Harvard Business Publishing conducted a global study to understand these needs and expectations and gather insights into the world of leadership development.

The results include insights into business challenges, future leadership skills, and the organizational goals that companies aim to achieve with the help of leadership development training programs. The report also examines the demand drivers for such programs, along with perceptions of key attributes and success factors.

EXPLORE THE FULL REPORT

Fulfillment at Work Requires Real Human-Centered Leadership

If what is being measured indicates what matters, employee fulfillment is not the focus for most organizations.

Today most organizations track employee engagement, which, despite its popularity, may not be ideal. The reason? Few employee engagement initiatives truly aspire to do anything for employees that doesn’t directly benefit the organization.

In contrast with employee engagement, working with an employee toward fulfillment is done, at least in large part, to benefit the individual. Fulfillment involves understanding each employee’s needs for wellness in its broadest sense.

DOWNLOAD THE PERSPECTIVE PAPER

- Research Report

- Infographic

- Webinar Recording

Driving Fulfillment at Work through Real Human-Centered Leadership

Client Story: Talent Development at State Street

How to Lead Authentically

How to Communicate for Impact

Checklist: Creating a Successful Leadership Development Program

How to Create a Successful Leadership Development Program

Leadership Fitness: The Path to Developing Human-Centered Leadership

The Case for Leadership Character

Developing Digital, Social, and Emotional Intelligence: How BFSI Leaders Can Capture the Full Potential of GenAI

Capturing the Full Potential of GenAI in BFSI

The Vicious Cycle Preventing Your People from Adapting to Change

Get the latest insights hot off the press.

Stay up to date on today’s global leadership challenges and strategies. Sign up to get the latest insights in your inbox.

- Business Email * Required

- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Let’s meet your leadership challenges, together

Want to write your own success story? Let’s co-create a leadership development solution that meets your challenges and delivers real impact for your organization’s performance.

Benefit from world-class thought leadership and expertise

Support your strategy with solutions tailored to your learners’ needs

Develop a culture of continuous learning with on-demand solutions

Let’s talk

Change isn’t easy, but we can help. Together we’ll create informed and inspired leaders ready to shape the future of your business.

© 2024 Harvard Business School Publishing. All rights reserved. Harvard Business Publishing is an affiliate of Harvard Business School.

- Privacy Policy

- Copyright Information

- Terms of Use

- About Harvard Business Publishing

- Higher Education

- Harvard Business Review

- Harvard Business School

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience. By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

Cookie and Privacy Settings

We may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Google reCaptcha Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

You can read about our cookies and privacy settings in detail on our Privacy Policy Page.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

The impact of engaging leadership on employee engagement and team effectiveness: A longitudinal, multi-level study on the mediating role of personal- and team resources

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Education Studies, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy

Roles Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Research Unit Occupational & Organizational Psychology and Professional Learning, KU Leuven, Belgium, Department of Psychology, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands

- Greta Mazzetti,

- Wilmar B. Schaufeli

- Published: June 29, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0269433

- Reader Comments

Most research on the effect of leadership behavior on employees’ well-being and organizational outcomes is based on leadership frameworks that are not rooted in sound psychological theories of motivation and are limited to either an individual or organizational levels of analysis. The current paper investigates whether individual and team resources explain the impact of engaging leadership on work engagement and team effectiveness, respectively. Data were collected at two time points on N = 1,048 employees nested within 90 work teams. The Multilevel Structural Equation Modeling results revealed that personal resources (i.e., optimism, resiliency, self-efficacy, and flexibility) partially mediated the impact of T1 individual perceptions of engaging leadership on T2 work engagement. Furthermore, joint perceptions of engaging leadership among team members at T1 resulted in greater team effectiveness at T2. This association was fully mediated by team resources (i.e., performance feedback, trust in management, communication, and participation in decision-making). Moreover, team resources had a significant cross-level effect on individual levels of engagement. In practical terms, training and supporting leaders who inspire, strengthen, and connect their subordinates could significantly improve employees’ motivation and involvement and enable teams to pursue their common goals successfully.

Citation: Mazzetti G, Schaufeli WB (2022) The impact of engaging leadership on employee engagement and team effectiveness: A longitudinal, multi-level study on the mediating role of personal- and team resources. PLoS ONE 17(6): e0269433. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0269433

Editor: Ender Senel, Mugla Sitki Kocman University: Mugla Sitki Kocman Universitesi, TURKEY

Received: December 29, 2021; Accepted: May 23, 2022; Published: June 29, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Mazzetti, Schaufeli. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: The data that support the findings of this study are available on Open Science Framework (OSF) website at the following link: https://osf.io/yfwgt/?view_only=c838730fd7694a0ba32882c666e9f973 . DOI: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/YFWGT .

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Multiple studies suggest that work engagement, which is defined as a positive, work-related state of mind characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption [ 1 ], is related to extremely positive outcomes, particularly in terms of employees’ well-being and job performance (for a narrative overview see [ 2 ]; for a meta-analysis see [ 3 ]).

Therefore, when work engagement is arguably beneficial for employees and organizations alike, the million-dollar question (quite literally, by the way) is: how can work engagement be increased? Schaufeli [ 4 ] has argued that operational leadership is critical for enhancing follower’s work engagement. Based on the logic of the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model [ 5 ], he reasoned that team leaders may (or may not) monitor, manage, and allocate job demands and resources to increase their follower’s levels of work engagement. In doing so, team leaders boost the motivational process that is postulated in the JD-R model. This process assumes that job resources and challenging job demands are inherently motivating and will lead to a positive, affective-motivational state of fulfillment in employees known as work engagement.

The current study focuses on a specific leadership style, dubbed engaging leadership and rooted in Self-Determination Theory (SDT) [ 6 ]. Engaging leaders inspire, strengthen, and connect their followers, thereby satisfying their basic psychological needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness, respectively. In line with the motivational process of the JD-R model, cross-sectional evidence suggests that engaging leaders increase job resources [ 7 ] and personal resources [ 8 ], which, in their turn, are positively associated with work engagement. So far, the evidence for this mediation is exclusively based on cross-sectional studies. Hence, the first objective of our paper is to confirm the mediation effect of resources using a longitudinal design.

Scholars have emphasized that “the study of leadership is inherently multilevel in nature” (p. 4) [ 9 ]. This statement implies that, in addition to the individual level, the team level of analysis should also be included when investigating the impact of engaging leadership.

The current study makes two notable contributions to the literature. First, it investigates the impact, over time, of a novel, specific leadership style (i.e., engaging leadership) on team- and individual outcomes (i.e., team effectiveness and work engagement). Second, it investigates the mediating role of team resources and personal resources in an attempt to explain the impact of leadership on these outcomes. The research model, which is described in greater detail below, is displayed in Fig 1 .

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0269433.g001

Leadership and work engagement

Leadership is defined as the way in which particular individuals–leaders–purposefully influence other individuals–their followers–to obtain defined outcomes [ 10 ].

A systematic narrative review identified twenty articles on leadership and work engagement [ 11 ] and showed that work engagement is positively associated with various person-centered leadership styles. The most pervasively used framework was transformational leadership, whereas authentic, ethical, and charismatic leadership was used much less. The authors conclude that "most of the reviewed studies were consistent in arguing that leadership is significantly correlated with and is affecting employee’s work engagement directly or via mediation” (p. 18) [ 11 ]. Moreover, they also conclude that research findings and inferences on leadership and engagement remain narrowly focused and inconclusive due to the lack of longitudinal designs addressing this issue. A recent meta-analysis [ 12 ] identified 69 studies and found substantial positive relationships of work engagement with ethical (k = 9; ρ = .58), transformational (k = 36; ρ = .46) and servant leadership (k = 3; ρ = .43), and somewhat less strong associations with authentic (k = 17; ρ = .38) and empowering leadership (k = 4; ρ = .35). Besides, job resources (e.g., job autonomy, social support), organizational resources (e.g., organizational identification, trust), and personal resources (self-efficacy, creativity) mediated the effect of leadership on work engagement. Although transformational leadership is arguably the most popular leadership concept of the last decades [ 13 ], the validity of its conceptual definition has been heavily criticized, even to the extent that some authors suggest getting “back to the drawing board” [ 14 ]. It should be noted that three main criticisms are voiced: (1) the theoretical definition of the transformational leadership dimensions is meager (i.e., how are the four dimensions selected and how do they combine?); (2) no causal model is specified (i.e., how is each dimension related to mediating processes and outcomes?); (3) the most frequently used measurement tools are invalid (i.e., they fail to reproduce the dimensional structure and do not show empirical distinctiveness from other leadership concepts). Hence, it could be argued that the transformational leadership framework is not very well suited for exploring the impact of leadership on work engagement.

Schaufeli [ 7 ] introduced the concept of engaging leadership , which is firmly rooted in Self-Determination Theory. According to Deci and Ryan [ 6 ], three innate psychological needs are essential ‘nutrients’ for individuals to function optimally, also at the workplace: the needs for autonomy (i.e., feeling in control), competence (i.e., feeling effective), and relatedness (i.e., feeling loved and cared for). Moreover, SDT posits that employees are likely to be engaged (i.e., internalize their tasks and show high degrees of energy, concentration, and persistence) to the degree that their needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness are satisfied [ 15 ]. This is in line with Bormann and Rowold [ 16 ]. Based on a systematic review on construct proliferation in leadership research, these authors recommended that leadership concepts should use SDT because this motivational theory allows a more parsimonious description of the mechanisms underlying leadership behaviors. These authors posited that the core of "narrow" leadership constructs "bases on a single pillar" (p. 163), and therefore predict narrow outcomes. In contrast to broad leadership constructs, the concept of engaging leadership is narrow because it focuses on leadership behaviors to explicitly promote work engagement.

Schaufeli [ 7 ] reasoned that leaders, who are instrumental in satisfying their followers’ basic needs, are likely to increase their engagement levels. More specifically, engaging leaders are supposed to: (1) inspire (e.g., by enthusing their followers for their vision and plans, and by making them feel that they contribute to something important); (2) strengthen (e.g., by granting their followers freedom and responsibility, and by delegating tasks); and (3) connect (e.g., by encouraging collaboration and by promoting a high team spirit among their followers). Hence, by inspiring, strengthening, and connecting their followers, leaders stimulate the fulfillment of their follower’s basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, respectively, which, in turn, will foster work engagement.

The underlying mechanisms of the relationship between engaging leadership and work engagement are a major focus of research, as the construct of engaging leadership was built upon the identification of the leadership behaviors that are capable of stimulating positive outcomes by satisfying needs. The literature on engaging leadership provides empirical evidence for its indirect impact on followers’ engagement by fulfilling followers’ basic needs. This finding is consistent across occupational sectors and cultural contexts [ 17 – 19 ]. Further, the observation of a partial mediation effect for need satisfaction suggests the presence of a direct relationship between engaging leadership and engagement [ 20 , 21 ]. In their behaviors, engaging leaders are likely to improve their job characteristics to the point of stimulating greater engagement among their employees. This assumption has been corroborated by a recent longitudinal study that delved deeper into the association between engaging leadership and needs satisfaction [ 22 ]. That study found that the relationship between engaging leadership and basic needs satisfaction is mediated by enhanced levels of job resources (among them were improved feedback and skill use and better person-job fit). The fulfilment of those needs, in turn, resulted in higher levels of work engagement. Therefore, perceived job resources seem to play a crucial role in the causal relationship between engaging leadership and basic needs satisfaction. This evidence found support in a later two-wave full panel design with a 1-year time lag, where engaging leadership promoted employees’ perception of autonomy and social support from colleagues [ 23 ]. In addition, a recent study by Van Tuin and colleagues [ 24 ] revealed that engaging leadership is associated with increased perceptions of intrinsic organizational values (e.g., providing a contribution to organizational and personal development) and satisfaction of the need for autonomy which, in turn, may boost employees’ level of engagement.

A recent study investigated the ways in which engaging leadership could boost the effects of human resource (HR) practices for promoting employees’ psychological, physical, and social well-being over time [ 25 ]. Teams led by an engaging leader reported higher levels of happiness at work and trust in leadership, combined with lower levels of burnout than their colleagues who were led by poorly engaging leaders. Happiness and trust played a key role in improving team member performance. These findings indicate that engaged leaders provide a thoughtful implementation of HR practices focused on promoting employee well-being, being constantly driven by their employees’ flourishing.

Another line of studies may reveal the causality between engaging leadership and work-related outcomes. A multilevel longitudinal study provided cross-level and team-level effects of engaging leadership [ 26 ]. Engaging leadership at T1 explained team learning, innovation, and individual performance through increased teamwork engagement at T2. Interventions targeting engaging leadership created positive work outcomes for leaders (e.g., autonomy satisfaction and intrinsic motivation) and decreased employee absenteeism [ 27 ]. However, cross-lagged longitudinal analyses indicate that employees’ current level of work engagement predicts their leaders’ level of engaging leadership rather than the other way around [ 23 ]. These findings imply that the relationship between engaging leadership and work engagement cannot be narrowed to a simple unidirectional causal relationship but rather exhibits a dynamic nature, where engaging leadership and work engagement mutually influence each other. The dynamic nature of engaging leadership has also been investigated through a diary study. The results suggest that employees enacted job crafting strategies more frequently on days when leaders were more successful in satisfying their need for connectivity [ 28 ]. Hence, leaders who satisfy the need for connectedness among their followers will not only encourage higher levels of engagement among their followers but also an increased ability to proactively adapt tasks to their interests and preferences.

Since transformational leadership is currently the most frequently studied leadership style, a summary of the similarities and differences in the proposed new conceptualization of leadership proposed (i.e., engaging leadership) must be provided.

A key difference between transformational and engaging leadership originates from their foundation. Whereas transformational leadership is primarily a change-oriented style, engaging leadership encourages employees’ well-being through the promotion of supportive relationships and is defined as a relationship-oriented leadership style [ 29 ].

Further similarities entail the combination of behaviors meant to foster employees’ well-being and growth. Transformational leaders act as role models admired and emulated by followers (idealized influence), encourage a reconsideration of prevailing assumptions and work practices to promote stronger innovation (intellectual stimulation), identify and build on the unique characteristics and strengths of each follower (individualized consideration), and provides a stimulating view of the future and meaning of their work (inspirational motivation) [ 30 ]. A considerable resemblance involves the dimensions of inspirational motivation and inspiring, which are, respectively, included in transformational and engaging leadership. They both entail recognizing the leader as a guiding light to a specific mission and vision, where individual inputs are credited as essential ingredients in achieving the shared goal. Thus, they both fulfill the individual need for meaningfulness. In a similar vein, transformational and engaged leaders are both committed to promote followers’ growth in terms of innovation and creativity. In other words, the intellectual stimulation offered by transformational leadership and the strengthening component of engaging leadership are both aimed at meeting the need for competence among followers.

Alternatively, it is also possible to detect decisive differences between the dimensions underlying these leadership styles. Transformational leadership entails the provision of personal mentorship (i.e., individualized consideration), while engaging leadership is primarily focused on enhancing the interdependence and cohesion among team members (i.e., team consideration). Furthermore, engaging leadership disregards the notion of idealized influence covered by transformational leadership: an engaging leader is not merely identified as a model whose behavior is admired and mirrored, but rather proactively meets followers’ need for autonomy through the allocation of tasks and responsibilities.

Empirical results lent further support to the distinctiveness between transformational and engaging leadership. The analysis of the factor structure of both constructs revealed that measures of engaging and transformational leadership load on separate dimensions instead of being explained by a single latent factor [ 31 ]. More recently, additional research findings pointed out that engaging and transformational leadership independently account for comparable portions of variance in work engagement [ 32 ]. However, this does not alter the fact that a certain overlap exists between both leadership concepts; thus, it is not surprising that a consistent, positive relationship is found between transformational leadership and work engagement [ 11 ].

In sum: a positive link appears to exist between person-centered leadership styles and work engagement. Moreover, this relationship seems to be mediated by (job and personal) resources. However, virtually all studies used cross-sectional designs, and the causal direction remains unclear. We followed the call to go back to the drawing board by choosing an alternative, deductive approach by introducing the theory-grounded concept of engaging leadership and investigate its impact on individual and team outcomes (see Fig 1 ).

Engaging leadership, personal resources, and employee engagement (individual level)

Serrano and Reichard [ 33 ], who posit that leaders may pursue four pathways to increase their follower’s work engagement: (1) design meaningful and motivating work; (2) support and coach their employees; (3 ) facilitate rewarding and supportive coworker relations, and (4) enhancing personal resources. In the present study, we focus on the fourth pathway. Accordingly, a cross-sectional study using structural equation modeling [ 8 ] showed that psychological capital (i.e., self-efficacy, optimism, resiliency, and flexibility) fully mediated the relationship between perceived engaging leadership and follower’s work engagement. Consistent with findings on job resources, this study indicated that personal resources also mediate the relationship between engaging leadership and work engagement. In a nutshel, when employees feel autonomous, competent, and connected to their colleagues, their own personal resources benefit, and this fuels their level of engagement.

In the current study, we use the same conceptualization of psychological capital (PsyCap) as Schaufeli [ 7 , 8 ], which slightly differs from the original concept. Originally, PsyCap was defined as a higher-order construct that is based on the shared commonalities of four first-order personal resources: “(1) having confidence (self-efficacy) to take on and put in the necessary effort to succeed at challenging tasks; (2) making a positive attribution (optimism) about succeeding now and in the future; (3) persevering toward goals and, when necessary, redirecting paths to goals (hope) to succeed; and (4) when beset by problems and adversity, sustaining and bouncing back and even beyond (resiliency) to attain success” (p. 10) [ 34 ]. Instead of hope, flexibility is included; that is, the capability of employees to adapt to new, different, and changing requirements at work. Previous research showed a high correlation ( r > .70) between hope and optimism, thus increasing the risk of multicollinearity [ 35 ]. This strong relationship points at conceptual overlap: hope is defined as the perception that goals can be set and achieved, whereas optimism is the belief that one will experience good outcomes. Hence, trust in achieving goals (hope) implies optimism. Additionally, hope includes "when necessary, redirecting paths to goals", which refers to flexibility. Finally, in organizational practice, the flexibility of employees is considered an essential resource because organizations are continuously changing, which requires permanent adaption and hence employee flexibility. In short, there are psychometric, conceptual, and pragmatic arguments for replacing hope by flexibility.

According to Luthans and colleagues [ 36 ], PsyCap is a state-like resource representing an employee’s motivational propensity and perseverance towards goals. PsyCap is malleable and open to development, thus it can be enhanced through positive leadership [ 37 ]. Indeed, it was found that transformational leadership enhances PsyCap, which, in turn, increases in-role performance and organizational citizenship behavior [ 38 ]. In a similar vein, PsyCap mediates the relationships between authentic leadership and employee’s creative behavior [ 39 ].

We argue that engaging leadership may promote PsyCap as well. After all, by inspiring followers with a clear, powerful and compelling vision, engaging leaders: (1) create the belief in their ability to perform tasks that tie in with that vision successfully, thereby fostering follower’s self-efficacy ; (2) generate a positive appraisal of the future, thereby fostering follower’s optimism ; (3) trigger the ability to bounce back from adversity because a favorable future is within reach, thereby fostering follower’s resiliency ; (4) set goals and induce the belief that these can be achieved, if necessary by redirecting paths to those goals, thereby fostering follower’s flexibility [ 38 ].

Furthermore, engaging leaders strengthen their followers and unleash their potential by setting challenging goals. This helps to build followers’ confidence in task-specific skills, thereby increasing their self-efficacy levels, mainly via mastery experiences that occur after challenging goals have been achieved [ 40 ]. Setting high-performance expectations also elevates follower’s sense of self-worth, thereby leading to a positive appraisal of their current and future circumstances (i.e., optimism ). Moreover, a strengthening leader acts as a powerful contextual resource that augments followers’ self-confidence and, hence, increases their ability to bounce back from adversity (i.e., resiliency ) and adapt to changing requirements at work (i.e., flexibility ).

Finally, by connecting their followers, engaging leaders promote good interpersonal relationships and build a supportive team climate characterized by collaboration and psychological safety. Connecting leaders also foster commitment to team goals by inducing a sense of purpose, which energizes team members to contribute toward the same, shared goal. This means that in tightly knit, supportive and collaborative teams, followers: (1) experience positive emotions when team goals are met, which, in turn, fosters their level of self-efficacy [ 40 ]; (2) feel valued and acknowledged by others, which increases their self-worth and promotes a positive and optimistic outlook; (3) can draw upon their colleagues for help and support, which enables to face problems and adversities with resiliency ; (4) can use the abilities, skills, and knowledge of their teammates to adapt to changing job and team requirements (i.e., flexibility ).

In sum, when perceived as such by followers, engaging leadership acts as a sturdy contextual condition that enhances their PsyCap. We continue to argue that, in its turn, high levels of PsyCap are predictive for work engagement; or in other words, PsyCap mediates the relationship between engaging leadership and work engagement.

How to explain the relationship between PsyCap and work engagement? Sweetman and Luthans [ 41 ] presented a conceptual model, which relates PsyCap to work engagement through positive emotions. They argue that all four elements of PsyCap may have a direct and state-like relationship with each of the three dimensions of work engagement (vigor, dedication, and absorption). Furthermore, an upward spiral of PsyCap and work engagement may be a source of positive emotion and subsequently broaden an employee’s growth mindset, leading to higher energy and engagement [ 42 , 43 ]. In short, PsyCap prompts and maintains a motivational process that leads to higher work engagement and may ultimately result in positive outcomes, such as job satisfaction and organizational commitment [ 44 ].

Psychological capital is a valuable resource to individuals [ 45 ] that fosters work engagement, as demonstrated in past research [ 46 ]. Hence, following the reasoning above, we formulate the following hypothesis:

- Hypothesis 1: Psychological capital (self-efficacy , optimism , resiliency , and flexibility) mediates the relationship between T1 employee’s perceptions of engaging leadership and T2 work engagement .

Engaging leadership, team resources, and work team effectiveness (team level)

So far, we focused on individual-level mediation, but an equivalent mediation process is expected at the aggregated team level as well. We assume that leaders display a comparable leadership style toward the entire team, resulting in a similar relationship with each of the team members. This model of leader-follower interactions is known as the average leadership style (ALS) [ 47 ]. This means that homogeneous leader-follower interactions exist within teams, but relationships of leaders with followers may differ between teams. The relationships between leadership and team effectiveness might be based on an analogous, team-based ALS-approach as well [ 48 ]. Following this lead, we posit that team members share their perceptions of engaging leadership, while this shared perception differs across teams. Moreover, we assume that these shared perceptions are positively related to team effectiveness.

An essential role for leaders is to build team resources, which motivate team members and enable them to perform. Indeed, the influence of leader behaviors on team mediators and outcomes has been extensively documented [ 49 , 50 ].

Most studies use the heuristic input-process-output (IPO) framework [ 51 ] to explain the relationship between leadership (input) and team effectiveness (output), whereby the intermediate processes describe how team inputs are transformed into outputs. It is widely acknowledged that two types of team processes play a significant role: “taskwork” (i.e., functions that team members must perform to achieve the team’s task) and “teamwork” (i.e., the interaction between team members, necessary to achieve the team’s task). Taskwork is encouraged by task-oriented leadership behaviors that focus on task accomplishment. In contrast, teamwork is encouraged by person-oriented leadership behaviors that focus on developing team members and promoting interactions between them [ 49 ]. The current paper focuses on teamwork and person-oriented (i.e., engaging) leadership.

Collectively, team resources such as performance feedback, trust in management, communication between team members, and participation in decision-making constitute a supportive team climate that is conducive for employee growth and development, and hence fosters team effectiveness, as well as individual work engagement. This also meshes with Serrano and Reichard [ 33 ], who argue that for employees to flourish, leaders should design meaningful and motivating work (e.g., through feedback and participation in decision making) and facilitate rewarding and supportive coworker relations (e.g., through communication and trust in management).

To date, engaging leadership has not been studied at the team level and concerning team resources and team effectiveness. How should the association between engaging leadership and team resources be conceived? By strengthening, engaging leaders provide their team members with performance feedback; by inspiring, they grant their team members participate in decision making; and by connecting, they foster communication between team members and install trust. Please note that team resources refer to shared, individual perceptions of team members, which are indicated by within-team consensus. Therefore, taken as a whole, the team-level resources that are included in the present study constitute a supportive team climate that is characterized by receiving feedback, trust in management, communication amongst team members, and participating in decision-making. We have seen above that engaging leaders foster team resources, but how are these resources, in their turn, related to team effectiveness?

The multi-goal, multi-level model of feedback effects of DeShon and colleagues [ 52 ] posits that individual and team regulatory processes govern the allocation of effort invested in achieving individual and team goals, resulting in individual and team effectiveness. We posit that the shared experience of receiving the team leader’s feedback prompts team members to invest efforts in achieving team tasks, presumably through team regulatory processes, as postulated in the multi-goal, multi-level model.

Trust has been defined as: “the willingness of a party to be vulnerable to the actions of another party based on the expectation that the other party will perform a particular action to the trustor, irrespective of the ability to monitor or control that other party” (p. 712) [ 53 ]. Using a multilevel mediation model, Braun and colleagues [ 54 ] showed that trust mediates the relationship between transformational leadership and performance at the team level. They reasoned that transformational leaders take into account a team member’s needs, goals, and interests, making them more willing to be vulnerable to their supervisor. This would apply even more for engaging leaders, which is defined in terms of satisfying basic follower’s needs. It is plausible that a team’s shared trust in its leader enhances the trust of team members in each other. That means that team members interact and communicate trustfully and rely on each other’s abilities, which, in turn, is conducive for team effectiveness [ 55 ].

Communication is a crucial element of effective teamwork [ 56 ]. Team members must exchange information to ascertain other members’ competence and intentions, and they must engage in communication to develop a strategy and plan their work. Several studies have shown that effectively gathering and exchanging information is essential for team effectiveness [ 57 , 58 ]. Furthermore, participation in decision-making is defined as joint decision-making [ 59 ] and involves sharing influence between team leaders and team members. By participating in decision-making, team members create work situations that are more favorable to their effectiveness. Team members utilize participating in decision-making for achieving what they desire for themselves and their team. Generally speaking, shared mental models are defined as organized knowledge structures that allow employees to interact successfully with their environment, and therefore lead to superior team performance [ 60 ]. That is, team members with a shared mental model about decision-making are ‘in sync’ and will easily coordinate their actions, whereas the absence of a shared mental model will result in process loss and ineffective team processes.

Taken together and based on the previous reasoning, we formulate the second hypothesis as follows:

- Hypothesis 2: Team resources (performance feedback , trust in management , team communication , and participation in decision-making) mediate the relationship between T1 team member’s shared perceptions of engaging leadership and T2 team effectiveness .

Engaging leadership, team resources, and work engagement (cross-level)

Engaging leaders build team resources (see above). Or put differently, the team member’s shared perceptions of engaging leadership are positively related to team resources. Besides, we also assume that these team resources positively impact work engagement at the individual level. A plethora of research has shown that various job resources are positively related to work engagement, including feedback, trust, communication, and participation in decision- making (for a narrative overview see [ 61 ]; for a meta-analysis see [ 62 , 63 ]). Most research that found this positive relationship between job resources and work engagement used the Job-Demands Resources model [ 5 ] that assumes that job resources are inherently motivating because they enhance personal growth and development and are instrumental in achieving work goals. Typically, these resources are assessed as perceived by the individual employee. Yet, as we have seen above, perceptions of resources might also be shared amongst team members. It is plausible that these shared resources, which collectively constitute a supportive, collaborative team climate, positively impact employee’s individual work engagement. Teams that receive feedback, have trust in management, whose members amply interact and communicate, and participate in decision-making are likely to produce work engagement. This reasoning agrees with Schaufeli [ 64 ], who showed that organizational growth climate is positively associated with work engagement, also after controlling for personality. When employee growth is deemed relevant by the organization this is likely to translate, via engaging leaders, into a supportive team environment, which provides feedback, trust, communication, and participative decision-making. Hence, we formulate:

- Hypothesis 3: Team resources (performance feedback , trust in management , team communication , and participation in decision-making) mediate the relationship between team shared perceptions of engaging leadership at T1 and individual team member’s work engagement at T2 .

Sample and procedure