100 Greatest Books of American Nature Writing

- American Nature Writing

- Literature & Fiction

- Essays & Correspondence

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: $11.69 $11.69 FREE delivery: Friday, April 12 on orders over $35.00 shipped by Amazon. Ships from: Amazon.com Sold by: Amazon.com

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Buy used: $8.03

Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) is a service we offer sellers that lets them store their products in Amazon's fulfillment centers, and we directly pack, ship, and provide customer service for these products. Something we hope you'll especially enjoy: FBA items qualify for FREE Shipping and Amazon Prime.

If you're a seller, Fulfillment by Amazon can help you grow your business. Learn more about the program.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the authors

The Best American Science And Nature Writing 2021 Paperback – October 12, 2021

There is a newer edition of this item:.

Purchase options and add-ons

“The stories I have chosen reflect where I feel the field of science and nature writing has landed, and where it could go,” Ed Yong writes in his introduction. “They are often full of tragedy, sometimes laced with wonder, but always deeply aware that science does not exist in a social vacuum. They are beautiful, whether in their clarity of ideas, the elegance of their prose, or often both.” The essays in this year’s Best American Science and Nature Writing brought clarity to the complexity and bewilderment of 2020 and delivered us necessary information during a global pandemic. From an in-depth look at the moment of the virus’s outbreak, to a harrowing personal account of lingering Covid symptoms, to a thoughtful analysis on how the pandemic will impact the environment, these essays, as Yong says, “synthesize, evaluate, dig, unveil, and challenge,” imbuing a pivotal moment in history with lucidity and elegance.

THE BEST AMERICAN SCIENCE AND NATURE WRITING 2021 INCLUDES • SUSAN ORLEAN • EMILY RABOTEAU • ZEYNEP TUFEKCI • HELEN OUYANG • HEATHER HOGAN BROOKE JARVIS • SARAH ZHANG and others

- Part of series The Best American Science And Nature Writing

- Print length 416 pages

- Language English

- Publication date October 12, 2021

- Dimensions 5.5 x 1.04 x 8.25 inches

- ISBN-10 0358400066

- ISBN-13 978-0358400066

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Similar items that may ship from close to you

From the Publisher

Editorial reviews.

"Where the collection shines brightest is in its ability to present human experiences and emotions in an intimate manner without sacrificing scientific rigor or specificity. Timely and informative, this anthology is sure to satisfy fans of science journalism." — Publishers Weekly —

About the Author

Ed Yong is a science writer who reports for The Atlantic . For his coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic, he won the Pulitzer Prize in explanatory reporting, the George Polk Award for science reporting, and other honors. His first book, I Contain Multitudes , was a New York Times bestseller. He is based in Washington, DC.

Jaime Green , series editor, is a science writer and essayist. Her work has appeared in The Atlantic, Slate, The Nation, The New York Times Book Review, Astrobites , and elsewhere. She is a lecturer at Smith College and the author of The Possibility of Life: Science, Imagination, and Our Quest for Kinship in the Cosmos.

Product details

- Publisher : Mariner Books (October 12, 2021)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 416 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0358400066

- ISBN-13 : 978-0358400066

- Item Weight : 2.31 pounds

- Dimensions : 5.5 x 1.04 x 8.25 inches

- #210 in Science Essays & Commentary (Books)

- #375 in Nature Writing & Essays

- #1,239 in Essays (Books)

About the authors

Ed Yong is an award-winning science writer who reports for The Atlantic. His writing has also appeared in National Geographic, the New Yorker, Wired, the New York Times, Nature, New Scientist, Scientific American, and more. He talked about mind-controlling parasites at the TED2014 conference, and his talk has been viewed more than 1.4 million times.

He is the winner of the Byron H. Waksman Award for Excellence in the Public Communication of Life Sciences (2016), the Michael E. DeBakey Journalism Award (2016), a National Academies Keck Science Communication Award (2010) and awards from the Association of British Science Writers for Best Science Blog (2014) and Best Communication of Science in a Non-Science Context (2012).

His first book, I CONTAIN MULTITUDES, about the amazing partnerships between microbes and animals, was published in 2016.

Jaime Green

Jaime Green is a science writer, essayist, editor, and teacher, and she is series editor of The Best American Science and Nature Writing. She received her MFA in Creative Nonfiction from Columbia, and her writing has appeared in Slate, Popular Science, The New York Times Book Review, American Theatre, Catapult, Astrobites, and elsewhere. She lives in Connecticut with her husband and son. Her book, The Possibility of Life, is about how we imagine extraterrestrial life, in science and science fiction.

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Start Selling with Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

- NONFICTION BOOKS

- BEST NONFICTION 2023

- BEST NONFICTION 2024

- Historical Biographies

- The Best Memoirs and Autobiographies

- Philosophical Biographies

- World War 2

- World History

- American History

- British History

- Chinese History

- Russian History

- Ancient History (up to 500)

- Medieval History (500-1400)

- Military History

- Art History

- Travel Books

- Ancient Philosophy

- Contemporary Philosophy

- Ethics & Moral Philosophy

- Great Philosophers

- Social & Political Philosophy

- Classical Studies

- New Science Books

- Maths & Statistics

- Popular Science

- Physics Books

- Climate Change Books

- How to Write

- English Grammar & Usage

- Books for Learning Languages

- Linguistics

- Political Ideologies

- Foreign Policy & International Relations

- American Politics

- British Politics

- Religious History Books

- Mental Health

- Neuroscience

- Child Psychology

- Film & Cinema

- Opera & Classical Music

- Behavioural Economics

- Development Economics

- Economic History

- Financial Crisis

- World Economies

- How to Invest

- Artificial Intelligence/AI Books

- Data Science Books

- Sex & Sexuality

- Death & Dying

- Food & Cooking

- Sports, Games & Hobbies

- FICTION BOOKS

- BEST NOVELS 2024

- BEST FICTION 2023

- New Literary Fiction

- World Literature

- Literary Criticism

- Literary Figures

- Classic English Literature

- American Literature

- Comics & Graphic Novels

- Fairy Tales & Mythology

- Historical Fiction

- Crime Novels

- Science Fiction

- Short Stories

- South Africa

- United States

- Arctic & Antarctica

- Afghanistan

- Myanmar (Formerly Burma)

- Netherlands

- Kids Recommend Books for Kids

- High School Teachers Recommendations

- Prizewinning Kids' Books

- Popular Series Books for Kids

- BEST BOOKS FOR KIDS (ALL AGES)

- Ages Baby-2

- Books for Teens and Young Adults

- THE BEST SCIENCE BOOKS FOR KIDS

- BEST KIDS' BOOKS OF 2023

- BEST BOOKS FOR TEENS OF 2023

- Best Audiobooks for Kids

- Environment

- Best Books for Teens of 2023

- Best Kids' Books of 2023

- Political Novels

- New History Books

- New Historical Fiction

- New Biography

- New Memoirs

- New World Literature

- New Economics Books

- New Climate Books

- New Math Books

- New Philosophy Books

- New Psychology Books

- New Physics Books

- THE BEST AUDIOBOOKS

- Actors Read Great Books

- Books Narrated by Their Authors

- Best Audiobook Thrillers

- Best History Audiobooks

- Nobel Literature Prize

- Booker Prize (fiction)

- Baillie Gifford Prize (nonfiction)

- Financial Times (nonfiction)

- Wolfson Prize (history)

- Royal Society (science)

- Pushkin House Prize (Russia)

- Walter Scott Prize (historical fiction)

- Arthur C Clarke Prize (sci fi)

- The Hugos (sci fi & fantasy)

- Audie Awards (audiobooks)

Make Your Own List

Nature » Nature Writing

Amy liptrot chooses the best of nature writing.

The Outrun by Amy Liptrot

Amy Liptrot , whose bestselling memoir The Outrun won the 2016 Wainwright Prize for nature writing, talks to Five Books about her favourite writing about landscape—and how her immersion in island life helped her recover from alcoholism.

Interview by Cal Flyn , Deputy Editor

Ring of Bright Water by Gavin Maxwell

The Drowned World by J. G. Ballard

Findings by Kathleen Jamie

Feral: Rewilding the Land, the Sea, and Human Life by George Monbiot

The Orkney Book of Birds by Tim Dean and Tracy Hall

1 Ring of Bright Water by Gavin Maxwell

2 the drowned world by j. g. ballard, 3 findings by kathleen jamie, 4 feral: rewilding the land, the sea, and human life by george monbiot, 5 the orkney book of birds by tim dean and tracy hall.

Y our bestselling first book, The Outrun, follows your story of recovery from alcoholism in Orkney, it’s a blend of memoir and nature writing: a very visceral sort of nature writing. The phrase ‘the nature cure’ springs to mind—is that something you believe in?

Rather than it being a philosophy I set out with, it was more something that I came to see the truth of through my own experiences. If the book is quite visceral, it’s because it was written at the same time as I was going through it, often from daily diaries that I keep. It’s set mainly during the time I lived on the small island of Papay and that’s also when I was writing the book.

This time in the wee house on the island was where I had the space to figure out what was going on with myself, how I’d ended up with an alcohol problem and in rehab and all that but also what helped me out of that was getting to know the island, the people and the culture and the coastline and the birds and the changes of the sea. I think often what I found most rewarding was not just, you know, going out for a walk, but time when I was actually in the landscape either immersing myself physically, by swimming in the sea, through the winter, or doing something like building the drystone walls. Going back to the same place as it changes through the seasons and physically linking myself to the land in some sort of way could be more rewarding and I could gain a deeper understanding of the place, and myself.

“I was doing more and better writing than I had done when I was pissed…that was helping me to keep sober”

While all that stuff has helped me—learning about the birds, connecting myself to something bigger than just me—while I am interested in that, what I’m specifically interested in is writing about the birds, and the place, and the fact that I had struck upon a great new source of material and was doing more and better writing than I had done when I was pissed…that was helping me to keep sober. So I was writing about the place and getting sober but that writing itself was keeping me sober and helping me with my recovery as well.

When you read other people writing about nature, or wild swimming, or other focuses of your own work, what do you look for, what do you admire?

I suppose I look for people that have more knowledge than me, who’ve done their research or…it’s a combination of both first-hand experience, often expressed in an unusual or poetic way, but I think that has to be combined with background research.

I also like it when somebody describes something that I have seen myself, but they’re able to do it in a better way than what I could have come up with—that recognition, I’ve seen that too! That’s true! And I’m glad that someone else has noticed it, or that they’ve corroborated my experience. That can be satisfying.

That reminds me of why I like reading film reviews, I often prefer to read them after I’ve seen the film, to get that sense of ‘yes! That’s it, that’s why that worked.’ Once I remember seeing you tweet that you’d learned as much from music criticism as you had from other nature books, do you still feel that?

Yes. I was actually a little nervous about doing this interview because there are lots of experts in the particular field of ecological writing, which I’m certainly not. Growing up I wasn’t a keen young ornithologist, or naturalist, although I was a keen reader but the books that I read as a kid were, you know, about boarding schools and babysitters and stuff far away from Orkney. Then, when I was a teenager and a student, I liked cities and rock’n’roll and angst, and I started writing a little for the music and style press.

“I was a keen reader but the books that I read as a kid were about boarding schools and babysitters”

Speaking of fringe characters, maybe that brings us to your first book choice: Gavin Maxwell’s Ring of Bright Water. Maxwell himself was a rather complicated character, but his book was just so captivating and gorgeous.

It’s a cult book that I had been aware of but never read, until my mum recommended it to me recently. I’ve actually read a kind of spin off book about it, Island of Dreams, by Dan Boothby, a chap who lived more recently on the island under the Skye bridge which Maxwell had owned. I did an event with him last year. So I was aware of the captivation Maxwell had held over a generation of young naturalists, often kind of loner type men, I think.

Particularly the first half of the book is just wonderful. He’s this aristocrat that just manages to acquire the lease on this lighthouse keeper’s house, and the sense of place that he evokes…he’s a brilliant writer. I got that recognition I mentioned before, of things that I myself have experienced in Orkney. He talks about the eider ducks and their mating calls: I’ve heard that! Or just the effects of the wind and the sea on the west coast of Scotland. That really struck something deep in me.

You can just imagine it—he’s very good with physical detail and how they descend the hill to the house, which is surrounded on three sides by sea, the ‘ring of bright water’.

It has a wonderful sense of freedom, perhaps because he’s doing something that people dream of. Living alongside an otter—laying aside whether or not someone should try to have an otter as a pet—it’s the dream isn’t it?

Yes, he’s retreated to this isolated place, where—although he gets a lot of help from people—he’s sort of alone, in the natural world, which is very appealing. As I think I discovered myself when I wrote about being on Papay, readers seem to relate to that, and it has a relationship to another book I thought about choosing, Walden, the archetype of this lone person in a small place in the countryside.

“The book is very of its time, it wouldn’t get published or written today”

But like Henry David Thoreau, Maxwell is…Well, the book can be read as a psychological portrait of a somewhat damaged person, actually. He’s from this privileged background and has, perhaps, problems with other human beings. That makes this lifestyle—and as it happens in the second half of the book, the relationship he has with his pet otters—attractive to him. It’s a weird portrait really. He’s brilliant, and funny, on the behaviour of the otters and how they differ from other kinds of pets. They’re not meant to be pets really. The book is very of its time, it wouldn’t get published or written today, I don’t think—someone taking wild animals from the Middle East and attempting to tame them with all the chaos that it causes and taking on local lads to help him out. But there’s something very idealistic about this world that he creates.

There’s a wonderful section when he takes the otter on the sleeper train and puts him in the sink, where he splashes around merrily.

Yes and the guard comes in in the morning and the otter’s actually in bed next to him, lying on its back with its hands over the cover and the guard says, ‘Would that be tea for one or two, sir?’

He’s a special and unusual guy who’d probably have been infuriating to deal with. He gets live eels sent up daily from London for the otters at great expense, huge amounts of money are spent on his outlandish plans—but you’re rooting for him, really, to be able to carry this off.

Get the weekly Five Books newsletter

The rural idyll Maxwell creates is so different to the world of your second book, JG Ballard’s The Drowned World. Here, instead of a paean to the pristine environment, it’s set in a post-apocalyptic catastrophe. What made you pick this?

Well, I think it’s a good example of using the natural world in fiction, and dystopian fiction, and I like the way that it uses the natural world, animals, and they are threatening and dangerous and strange rather than a source of solace or escape. They are the opposite. It was ahead of its time, it could almost be seen as a novel about climate change: ‘de-evolution’ is the word used.

Ballard is a master of the surreal but revealing detail, often using plants and animals. I remember one section in High Rise, a bit that stuck with me, was a seagull picking a diamante from a pair of sunglasses abandoned at the top of a building. And in The Drowned World, he has what was London, now flooded, and all these hotels now silted up where only the top floors are still accessible. And when it’s drained there are all these sea creatures—giant anemones and starfish and kelp—in Leicester Square, and dinghies stranded on traffic islands. This idea of the familiar being made strange and awful is part of what creates his distinctive, and highly influential, atmosphere.

The main character is almost perversely attracted to this new, ruined, world.

Kerans, the main character, the biologist—when the other people are retreating further towards the poles where it’s cooler, he’s going deeper in towards the equator…into the heart of darkness…A lot of Ballard’s books are about dark psychological stuff. But I can relate to being attracted to some of the more brutal elements of nature. I chose to go and live on a small Orkney island during winters rather than summers, when most people would choose the opposite. The big winds and the wild seas that sometimes cause damage are appealing to me, in their power and inhospitability.

Is there something in you that is drawing you back there? Or was it a time of your life when you needed it, when it suited you?

Absolutely. In Orkney, you were working for the RSPB looking for corncrakes. Kathleen Jamie, in your third book, Findings, has an essay about corncrakes. Was that something you came across before, or after?

Good question! I was writing a series of columns for Caught by the River, a nature writing website, and I think I’d already done the first four and my friend Morag said to me, ‘Have you read any Kathleen Jamie?’ and directed me towards Findings, which I just gulped up. It was interesting to discover that she was operating in some of the same territory that I was trying to—in an extremely skillful and much more developed way. And a little bit of me was like: ‘Damn you Jamie! Back off!’

“I spent two summers being out every night, looking and listening for corncrakes”

But I’ve gone back and looked at this book recently, and realised how influential she has been on me—just by showing what can be done with the nature essay. I think she’s wonderful. She’s a poet, which you can just see in her work, in her tight descriptions. She describes the weather in Orkney as there being ‘frequent scraps of rainbow,’ which is just right. So yes, it wasn’t like I read Jamie’s stuff and thought I’d go and do something similar, but during the writing of The Outrun, I came across her near the beginning.

The first time I came across your writing was an essay for Aeon , “The Corncrake Wife”. Perhaps it’s the quest element, the idea of these corncrakes being so tricky to find, that makes them so compelling to read about.

Yes—I spent two summers being out every night, looking and listening for corncrakes, and I only ever saw one of them. They almost became a sort of phantom, or symbol, or a way of allowing me to see the island as much as find the bird. There’s a lot of mythology and theory associated with them. It was something that I randomly applied for, got the job, and working for the RSPB opened a lot of doors for me. That was the beginning of my deeper interest in the natural world and realising, through writing and also through reading people like Jamie, that it was something that I could write about.

I’ve given this book to a number of people and recommended it to more. She’s a poet, but she’s also a realist—she talks about details of modern-day Scottish life, the people that she meets, and a little bit about her own daily life: she has to be back to pick the kids up from school, things like that. And she’s just really smart, in terms of the research that she does and sometimes, not in a too heavy handed way, but the way she relates it to wider ecological issues.

“They almost became a sort of phantom, or symbol, or a way of allowing me to see the island as much as find the bird”

The title essay, “Findings”, is about beach-combing and the things that she finds. I like how she describes, on the same poetic level, the gannet skull that she finds but also the unusual plastic objects she finds washed up, which is obviously about the pollution of the seas. Her tone is really well judged and her beautiful, clear-eyed descriptions show the reality of what’s going on on the coastlines.

And a very different style to George Monbiot, next, with Feral. Is it accurate to describe him as a polemicist? He comes from a very different direction.

This is a bold and radical book, which introduced me to several new ideas and changed the way I look at the countryside in quite a challenging way. As you say, it’s different to Jamie in that he’s unafraid of stating his opinions. The book broadly is about this idea of ‘re-wilding,’ which was a new idea to me. A really exciting one, I found it. All the stuff about the return of large predators and the effects that the loss of the top predators has had on the landscape was really eye-opening, and also—particularly as a sheep-farmer’s daughter—it was quite difficult to read some of his opinions. Because he hates sheep. Or rather, he hates the effect that sheep have had on the uplands of this country.

He describes sheep farming as ‘having done more damage to the living systems of this country than either climate change or industrial pollution.’

Yes! Which is a really radical idea. But I think he might be right.

How does that feel, coming from a sheep-farming family?

Well, I guess there might be some differences between the Scottish islands and the uplands of Wales, in that they weren’t really wooded places in the first place. But I think I’m open to looking at the way that agriculture is very protected, sometimes, and it’s difficult to criticise. Perhaps we should be looking at new ways of using the land, and diversifying what landowners and farmers do.

My dad is an organic farmer, which is slightly less intensive and slightly more varied, and has a lower impact on the land, but after reading Monbiot, I do look out, even in Orkney, and see the ‘green deserts’ he describes, the monocultures of grassland for beef.

“After reading Monbiot, I do look out even in Orkney and see the ‘green deserts’ he describes”

However, I put Monbiot in a category with two American writers I love, Naomi Klein and Rebecca Solnit, in that he’s an outspoken writer on conservation and the environment, but he does offer some mitigations and some ways forward: in his ideas about re-wilding, and talking about localisation and how landowners can diversify or be more creative about how the land is used and the species that can possibly be introduced. So while it is very challenging and difficult, there are also some exciting ideas and suggested ways forward that could provide some blueprint.

He uses very emotive language, phrases like ‘sheep-wrecked’—do you think that is necessary to shock people, almost, to make people look afresh at landscapes, the way you described?

Let’s move on to your last book, the illustrated Orkney Book of Birds. You say you’ve learnt a great deal from this book. Why would you recommend it?

I wouldn’t recommend it to everyone, just to people who are in or visiting Orkney. It’s a little masterpiece of local knowledge and research, presented extremely readably. It’s a guidebook, and over the last few years, as a novice birdwatcher in Orkney, it’s the nature book I return to the most. Unlike the Collins bird guide, it only includes the species found in Orkney, which is different to what you find in other places, and includes lovely details such as the Orcadian dialect names for all the different birds: puffins are ‘tammie norries’, and lapwings are ‘teeicks’.

“In Orkney, puffins are ‘tammie norries’, and lapwings are ‘teeicks”

It also includes their specific local locations, the different islands or habitats they are found on, their numbers and how they have increased or declined over the years, looking at data from local surveys. Then it often has specific, almost poetic, facts, like how there was a starling roost on the Kirkwall lifeboat, or that most farms in Orkney tend to have a pair of pied wagtails. It really helped me to appreciate my local patch. The birds I’m now most knowledgable on are the seabirds and the farmland birds that you get in Orkney.

And as well as the text, which is fabulously researched and written by Tim Dean, there are also the illustrations by Tracy Hall, which are beautiful. What I particularly like is that they are shown in their specific Orkney locations where they are found, you can see identifiable buildings and coastlines. I think the corncrakes are on the island of Egilsay, which has been a place that has encouraged them. I love this book.

Having moved to Yorkshire, do you feel you’ve had to learn a whole new population of birds and wildlife?

Well, I’m just starting off! I was out for a walk yesterday and I saw some grey wagtails, a bird we don’t get in Orkney. There are so many species down here that you don’t get in Orkney. I hear tawny owls, hooting at night, which feels very exotic to me, as the only owls we have in Orkney are the short-eared owls, which are silent. So I’ve been learning a new landscape. But I can’t help comparing it—I keep saying ‘oh, we don’t get that at home!’ I do feel like Orkney is my heartland, my local patch, and I can see myself returning there at some point. I’m just having an interlude here in Yorkshire. The islands are really…particularly the curlews and oystercatchers and the gannets and the tysties [black guillemots] are the birds that speak most to my heart, that I grew up with and got to know deeply over the years that I lived there.

It’s something that is dyed in you, almost. What you said there reminded me of Nan Shepard, and the way she was always going in and out of the same hills over years and decades, how rich those layers of experience can become. It’s all imbued with this history of yourself.

Yes. Although I said that I wasn’t a birdwatcher when I was a kid, I grew up on a farm so I was aware of the birds, and knew their names and their calls were already in me. I think it was there all along, I just avoided admitting it for a long time. So it’s been very rewarding to study it all and write about it more closely.

April 13, 2017

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]

Support Five Books

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you've enjoyed this interview, please support us by donating a small amount .

Amy Liptrot

Amy Liptrot's first book, The Outrun was a Sunday Times bestselling title and winner of the 2016 Wainwright Prize for nature writing. It was also shortlisted for the Wellcome Book Prize, for the Saltire Non-Fiction Book of the Year, and was recently announced as in the running for narrative non-fiction book of the year at the British Book Awards.

We ask experts to recommend the five best books in their subject and explain their selection in an interview.

This site has an archive of more than one thousand seven hundred interviews, or eight thousand book recommendations. We publish at least two new interviews per week.

Five Books participates in the Amazon Associate program and earns money from qualifying purchases.

© Five Books 2024

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Book News & Features

The workings of nature: naturalist writing and making sense of the world.

Genevieve Valentine

Buy Featured Book

Your purchase helps support NPR programming. How?

- Independent Bookstores

"In every generation and among every nation, there are a few individuals with the desire to study the workings of nature; if they did not exist, those nations would perish."

-- Al-Jahiz, The Book of Animals

In 185 AD, Chinese astronomers recorded a supernova. Among more detached details of its appearance, there is this: "It was like a large bamboo mat. It displayed the five colors, both pleasing and otherwise."

The attempt to ground the unknown within the familiar — and the editorial aside of "otherwise" — cuts to the heart of naturalist writing. Nearly 2000 years later, Carl Sagan did the same in Cosmos , condensing astronomy to its component parts: facts and wonder.

We've been curious about the natural world since before recorded time; the history of naturalism is human history. By the ninth century, al-Jahiz's multi-volume History of Animals combined zoological folklore with scientific observation, including theories of natural selection. In the early 20th century, Sioux author Zitkala-Ša wrote landscapes intertwined with the personal, which became a model for the form. In 1962, Rachel Carson's ecological manifesto Silent Spring was a deciding factor in banning DDT.

The best naturalist writing delivers both a secondhand thrill of obsession and a jolt of protectiveness for what's been discovered. Some of it reveals as much about the author as the surroundings. (Carl Linnaeus' 1811 Tour of Lapland manuscript cuts off a paragraph about wedding customs mid-sentence, picking up again with a breathless catalog of marsh plants.) And naturalists themselves are shaped by the lure of landscapes on the page. Robert MacFarlane's Landmarks explores the British countryside using others' writing as an interior map that challenges him to approach familiar places in new ways.

We love reading about nature for the same reason naturalists love being ankle-deep in marshes: Nature provides enough order to soothe and enough entropy to surprise. It's also why so many involve a person in the landscape; understanding our place in the world is as important as understanding the world itself. We read the work of naturalists to capture that sense of discovery made familiar. They present worlds we've never seen, and make us care as if they were our own backyards.

Not every naturalist sets out to be an activist; this is a literary tradition as much as a scientific one. But there are threads that connect naturalist literature, across continents and centuries. It's driven by an environmental curiosity that integrates the scientific and the spiritual; facts inspire wonder, rather than quench it. And every piece of naturalist literature, from al-Jahiz to today, makes a case for preserving the world it sees.

The Invention of Nature

Some naturalists actually do try to encompass the world entire. In The Invention of Nature , Andrea Wulf follows Alexander Humboldt's expeditions in Latin America and European royal courts, painting a portrait of a man whose hunger for knowledge — and constant pontificating about it — bordered on caricature. Humboldt's legacy is the 'web of life' his work conveyed to a lay audience. That interconnectedness made him an early conservationist; by 1800 he was noting adverse effects "when forests are destroyed, as they are everywhere in America by European planters, with an imprudent precipitation."

But he wasn't the first to catalog the systems of life. A century before Humboldt, German-born naturalist Maria Sybilla Merian was in Surinam, recording her life's passion: butterflies, moths, and insects. Chrysalis , Kim Todd's biography of this amateur scientist who established the idea of a life cycle, aims for a sly impression of Merian, down to the subject matter: "Insects," Todd explains, "generally gave off a whiff of vice." Merian's engravings made life cycles palpable for a public who still believed rotten meat spontaneously transformed into flies; it was impressive enough to change assumptions about the natural world (though Merian's credit waned as male scientists began absorbing her work into their own).

Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

To write about the world around us is to write about people, whether cataloging the unknown or coming to terms with one's backyard. This is the dynamic at the heart of Annie Dillard's Pilgrim at Tinker Creek , which carries a touch of the hymnal (and a grim streak that has a grandmother in Merian's engraving of a tarantula devouring a bird), and Barbara Hurd's Stirring the Mud , a love letter swamps, bogs, and "the damp edges of what is most commonly praised." And few naturalists write themselves into their landscapes quite so drily as M. Krishnan. The essays in Of Birds and Birdsong carry a sense of magical realism; always scientifically rigorous (his bird descriptions are those of a man looking for a particular friend in a crowd of thousands), Krishnan writes himself as a resigned meddler in avian affairs; he could try to be invisible among nature's bounty, but then who'd train his pigeons?

Of course, some writers have to fight to be seen on the landscape at all. Enter The Colors of Nature , an anthology of nature writing by people of color edited by Alison H. Deming and Lauret E. Savoy, providing deeply personal connections to — or disconnects from — nature. Jamaica Kincaid's "In History" considers naturalism in the aftermath of colonialism, asking a crucial question for naturalism in a global context: "What should history mean to someone who looks like me?" And Joseph Bruchac's travel diary is pragmatism shot through with hope; "Our old words keep returning to the land."

The Colors of Nature

For others, the internal landscape and that hope for the natural world must be rediscovered in tandem. In Braiding Sweetgrass , botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer tackles everything from sustainable agriculture to pond scum as a reflection of her Potawatomi heritage, which carries a stewardship "which could not be taken by history: the knowing that we belonged to the land." That sense of connection, or the loss of it, is the spine of the book: mucking out a pond is a microcosm, agriculture becomes rumination on symbiosis, and mast fruiting of pecan trees parallels human and plant communities.

It's a book absorbed with the unfolding of the world to observant eyes — that sense of discovery that draws us in. Happily for armchair naturalists, mysteries of the natural world never stop unfolding; but increasingly, a sense of impending doom accompanies the delight of knowledge. Kimmerer mentions a language between trees as something awaiting more specific study; it arrives later this year in Peter Wohlleben's The Hidden Life of Trees . A no-nonsense writing style — he came, he studied, here's how to date a forest via its weevil population — frames a deeply conservationist argument: Trees harbor not only ecosystems, but feelings, vocabulary, and etiquette. Hidden Life is designed to be an arboreal Silent Spring .

For some places, however, no revelations are yet possible; the world being studied is simply too mysterious to be yet wholly understood. With meditative prose, 1986's Arctic Dreams chronicled Barry Lopez's expeditions in an ecosystem so punishing half an animal population can die every winter, and so otherworldly animal fat is preserved on bones after a century. "Something eerie ties us to the world of animals," he says, and it's both a warning and a promise. In The Whale: In Search of the Giants of the Deep, Philip Hoare's marine obsession is similarly dreamlike; for him, what we know about whales and how they make us feel is deeply linked. After all, our 'discovery' of them is still in its first blush. Sperm whales were first filmed in 1984; "We knew what the world looked like before we knew what the whale looked like." The only absolute conclusion in his book is a stern one: Humanity's damaging effects on nature and its fascination with the unknown has been devastating; if we're going to keep whales long enough to know them, that fascination will have to take a more protective turn.

To write about the world around us is to write about people, whether cataloging the unknown or coming to terms with one's backyard. These narratives are crucial, especially now — stories of the worth of nature, even just as a mirror of ourselves, build a narrative in which nature's something worth saving. It's imperfect; making nature an object rather than a subject prevents us from seeing ourselves as part of natural patterns of cause and effect. But in The Colors of Nature, Aileen Suzara pins it down: "The landscape is a narrative, not a narrator, because it has no human voice." The human voice that looked at the dark and saw a dying star is heard 2000 years later. If we're going to have another 2000 years, there's no time like the present to start listening.

Genevieve Valentine's latest novel is Icon.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Top 10 nature memoirs

Moving on from writing that holds the natural world at arm’s length, authors have begun using intimate life to show nature as a protagonist in itself

T he lockdowns of 2020/2021 galvanised and expanded a readership drawn to writing about the natural world. For the fortunate, the pause and hush offered space to witness the seasons unfolding, to hear voices other than our own, and to realise “our” story is deeply entangled with other lives. Undisturbed by the hum of road and shipping traffic, birdsong and the buzz of pollinators were amplified in our days’ soundtracks, and whales were recorded for the first time speaking in complex “sentences” . With the grave threat posed by the compound climate, ecological and biodiversity crises, a need and longing to repair our connection to the living world is keenly felt by many, and literature is playing a key role.

While the early nature writing canon leaned towards natural history – often at arm’s length, often written by a man out in a “wild” place – recent forms are bringing the issues of our time closer to home in memoir, making vivid the lives of others – human and not. The diversification of authors and of the places, cultures, and beings represented are lending vitality to the genre. A current fascination with the intelligences of the “‘more-than-human” world is firmly placing nature as protagonist rather than in service to a human plot.

Given the Arctic is such an active protagonist in climate change, it is perhaps surprising that the genre has seldom ventured to the far north. I was lucky enough to spend half a decade in Iceland, leaning into its genius loci. I still do, whenever I get the chance: it is a place that allows me to think differently. My debut The Raven’s Nest is an ecological memoir set in its otherworldly Westfjords. I call it ecological because, in life as on the page, it manifests everything as relational and interdependent. Entangled with the story of my marriage to an Icelander, other stories – of people, ravens, storms, the supernatural, life and death – build a weave in cycles of light and dark, into the titular nest. Amid volcanic eruptions and melting ice sheets, people and place are continuous. We are increasingly aware that the far north is not remote but central – in the regulation of climate, ocean currents, and therefore in all our futures. Treading a fine line between insider and outsider, I felt compelled to record what I witnessed and became a part of.

What happens when we listen to the voices which make a place? How might we feel our entanglements with the world to know it as home and treat it as such, even when we are unsure where we belong to? These books, many with a focus on the far north and spanning nearly a century, have inspired how I explore this interplay between place, people, living, thought and the body.

1. A Woman in the Polar Night by Christiane Ritter In the winter of 1933/4 Ritter, an Austrian painter and self-proclaimed “housewife”, makes the radical decision to join her hunter-trapper husband and a Norwegian hunter in Arctic Spitsbergen, living together in a tiny hut. Often alone for long spells, her mundane chores and her will to survive the extremes uncover marvels, both in the place and her spirit. The imagistic prose is exhilarating. Written as a journal – with long periods tellingly absent – we witness her transformation as she relinquishes herself to this place.

2. The Living Mountain by Nan Shepherd This dazzling gem written in the 1940s is an intimate journey into the Cairngorms Massif. Shepherd swims naked in clear mountain lochs, walks to be with the mountains as companions, naps on them, looks at them upside down between her legs, thrills in the glow of sparks from her hobnail boots while nightwalking. She probes at the possible, but there are no heroics here. The summit is not the point. It is rather to find new thoughts in the material – in the here and now – which is also metaphysical.

3. Arctic Dreams: Imagination and Desire in a Northern Landscape by Barry Lopez Written in the 1980s, this is a portal into the Arctic before it was synonymous with climate change. Lopez’s masterwork is the result of years of travel, delving into its histories, fauna, ice, water, stars, light and people – both his Indigenous companions and visiting scientists and workers. Scientifically rigorous, poetic and often reverent in its tone, Lopez builds a prismatic portrait. We are in the hands of a truly reliable and loving guide: an ecologist with a profound respect for knowledge of all kinds, so humble and curious that his words and thoughts seem almost prayerful.

4. Wild: An Elemental Journey by Jay Griffiths Partly in response to a debilitating depression, Griffiths makes a seven-year journey across the Earth to which she gives everything, in search of the meaning of “wild” – in the world and in herself. Using the elements as a structural device – Earth, Water, Fire, Wind (and she adds Ice) – she travels to the Peruvian Amazon, the Indonesian Ocean, the Australian bush, the mountains of West Papua, and the Canadian Arctic. Through sharp and heartful observation of these places and a high regard for the indigenous knowledges she encounters, her philosophical inquiry takes us to far corners of our minds, using a deeply embodied prose and wild language that writhes on the tongue.

5. Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer Kimmerer’s world is animate and abundant. She is in love with it, and moves through it as if it loves her back. She asks what might “right relationship” look like in a damaged world? What is the language of reciprocity, the “grammar of animacy”? Drawing on her native Potawatomi culture, twined with her training as a bryologist, she shows us how science and culture, myth and reality are not opposed but live within one another.

6. Land of Love and Ruins by Oddný Eir This beautiful, pioneering autofiction mainly set in Iceland is a deceptively small and easy text which covers vast swathes of philosophical terrain in a variety of landscapes and homescapes. Written as a journal marked by feast days, equinoxes and the stages of the moon, Eir’s sensuous and breezy narrative voice explores what shape of existence might allow a woman to tend well to all those relationships which make her: to her living kin, to her ancestors, to a partner and to the Earth itself, without losing herself.

7. Small Bodies of Water by Nina Mingya Powles A series of loosely connected essays, Small Bodies of Water’s luscious prose flows deftly between moments in the author’s international life, each so vividly and sensuously portrayed as to immerse us in a world, and the age at which that world was lived. We move with Powles across time and geography – from adolescence to adulthood , from Borneo to New Zealand to London – exploring the fluid (and sometimes suspended) nature of identity and home. Deeply embodied, the pleasures of swimming, food, languages, flora and fauna are keenly felt as anchors, and an almost aqueous merging of the bloodline across generations pulses through it.

8. Soundings by Doreen Cunningham A failed relationship and resulting professional and financial ruin compel former climate journalist Cunningham to make a bold move. Taking out a bank loan, she travels with her young son along the migration route of the grey whales, from Mexico to the Canadian Arctic, back to a family of Iñupiaq whale hunters who took her in as one of their own years earlier on a research trip. Cunningham’s honouring of the hunters’ culture is nuanced by this entanglement, and the endless wait of the whale hunt is made fascinating by her quiet observations. The protagonists make a deeply refreshing triad: a single mother travelling with her child, learning from the whales how to parent.

9. On Time and Water by Andri Snær Magnason A poetic and heartful treatise which argues that we lack the metaphors to carry the enormity of the ecological crisis. We do not – cannot – truly understand words such as “climate change” and “ocean acidification”, so cannot respond appropriately. Approaching them slant through myth and family history (his grandparents honeymooned as participants in one of the first Icelandic glaciological surveys) Magnason’s simple proposition elicits a shift in perspective to connect to the future “in an intimate and urgent way”. By invoking our time as “the handshake of generations” – the period inhabited by those who have loved us, ourselves, and those who we will love in the future – he brings the impacts of this unknown future close to our hearts.

10. Islands of Abandonment: Life in the Post Human Landscape by Cal Flyn In rigorously researched and poetic prose Flyn manages a rare feat: an angle on nature writing that is entirely new. Travelling to places that humans once inhabited, then destroyed and (mostly) left, she returns to see what has thrived in their wake. From the abandoned buildings of Detroit to Chernobyl to the “bings”(spoil heaps) of Scotland’s West Lothian, she finds a strange kind of abundance. Flyn proposes that rather than purely lamenting a lost vitality in the natural world, we might also reframe and cultivate our aesthetic sensibilities to see, and appreciate, the life in ruins.

The Raven’s Nest by Sarah Thomas is published by Atlantic Books. To help the Guardian and Observer, order your copy from guardianbookshop.com . Delivery charges may apply.

- Science and nature books

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

What is nature writing?

What we talk about when we talk about nature writing.

“Nature writing can be defined as non-fiction or fiction prose or poetry about the natural environment.” This is actually its definition on Wikipedia.

For the purposes of this prize, we're accepting only non-fiction prose submissions (see last week's resources on breaking down the brief ), but in general, nature writing can mean many more things and cover lots of different ideas. As such, there’s a whole variety of approaches to writing a book in this genre. Different types of nature writing books can include: factual books such as field guides, natural history told through essays, poetry about the natural world, literary memoir and personal reflections.

Typically, nature writing is writing about the natural environment. Your book might take a look at the natural world and examine what it means to you or what you’ve encountered in the environment. You could frame this idea through a personal lens.

Perhaps you want to take a more focused or factual approach and look at individual flora and fauna in detail. Recent books that we’ve enjoyed have looked at topics such as beekeeping, owls, social and cultural history, trees, swimming, cows and have offered personal observation and reflection on their chosen topics.

You might be writing about the landscape, from farming to remote islands or city life. You may want to write about the fauna and flora of a whole region, or just one animal or a single tree. You don’t need to go out into the wilderness to write about nature and you don’t need to be hiking for three months in a remote area either. Most importantly, we believe the best books on nature writing convey a clear sense of place and mainly focus on the natural world and our human relationship with it.

The Nan Shepherd Prize aims to find the next big voice in nature writing from emerging writers, and we can’t wait to read about what nature means to you.

- Read an academic paper on New Nature Writing here .

- ‘Land Lines’ was a two-year project funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, and is a collaboration between researchers at the Universities of Leeds, Sussex and St Andrews. The project carried out a sustained study on modern British nature writing, beginning in 1789 with Gilbert White’s seminal study, The Natural History of Selborne, and ending in 2014 with Helen Macdonald’s prize-winning memoir, H is for Hawk. You can look at their website here .

- Read about nature writing throughout history (this is a US perspective) here .

- Read about which nature books have inspired today’s contemporary nature writers here .

- Read this guide to nature writing from Sharmaine Lovegrove, publisher of Dialogue Books, who teamed up with the Forestry Commission to find undiscovered nature writers here .

Over @NanPrize we’ve been sharing examples of our favourite nature writing books, so if you want to see some specific examples of recent favourites, that might be a good place to start. We’ve also got a collection here which will give you an idea as to what books we like to publish in the nature writing genre.

What is Nature Writing?

Definition and Examples

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

Nature writing is a form of creative nonfiction in which the natural environment (or a narrator 's encounter with the natural environment) serves as the dominant subject.

"In critical practice," says Michael P. Branch, "the term 'nature writing' has usually been reserved for a brand of nature representation that is deemed literary, written in the speculative personal voice , and presented in the form of the nonfiction essay . Such nature writing is frequently pastoral or romantic in its philosophical assumptions, tends to be modern or even ecological in its sensibility, and is often in service to an explicit or implicit preservationist agenda" ("Before Nature Writing," in Beyond Nature Writing: Expanding the Boundaries of Ecocriticism , ed. by K. Armbruster and K.R. Wallace, 2001).

Examples of Nature Writing:

- At the Turn of the Year, by William Sharp

- The Battle of the Ants, by Henry David Thoreau

- Hours of Spring, by Richard Jefferies

- The House-Martin, by Gilbert White

- In Mammoth Cave, by John Burroughs

- An Island Garden, by Celia Thaxter

- January in the Sussex Woods, by Richard Jefferies

- The Land of Little Rain, by Mary Austin

- Migration, by Barry Lopez

- The Passenger Pigeon, by John James Audubon

- Rural Hours, by Susan Fenimore Cooper

- Where I Lived, and What I Lived For, by Henry David Thoreau

Observations:

- "Gilbert White established the pastoral dimension of nature writing in the late 18th century and remains the patron saint of English nature writing. Henry David Thoreau was an equally crucial figure in mid-19th century America . . .. "The second half of the 19th century saw the origins of what we today call the environmental movement. Two of its most influential American voices were John Muir and John Burroughs , literary sons of Thoreau, though hardly twins. . . . "In the early 20th century the activist voice and prophetic anger of nature writers who saw, in Muir's words, that 'the money changers were in the temple' continued to grow. Building upon the principles of scientific ecology that were being developed in the 1930s and 1940s, Rachel Carson and Aldo Leopold sought to create a literature in which appreciation of nature's wholeness would lead to ethical principles and social programs. "Today, nature writing in America flourishes as never before. Nonfiction may well be the most vital form of current American literature, and a notable proportion of the best writers of nonfiction practice nature writing." (J. Elder and R. Finch, Introduction, The Norton Book of Nature Writing . Norton, 2002)

"Human Writing . . . in Nature"

- "By cordoning nature off as something separate from ourselves and by writing about it that way, we kill both the genre and a part of ourselves. The best writing in this genre is not really 'nature writing' anyway but human writing that just happens to take place in nature. And the reason we are still talking about [Thoreau's] Walden 150 years later is as much for the personal story as the pastoral one: a single human being, wrestling mightily with himself, trying to figure out how best to live during his brief time on earth, and, not least of all, a human being who has the nerve, talent, and raw ambition to put that wrestling match on display on the printed page. The human spilling over into the wild, the wild informing the human; the two always intermingling. There's something to celebrate." (David Gessner, "Sick of Nature." The Boston Globe , Aug. 1, 2004)

Confessions of a Nature Writer

- "I do not believe that the solution to the world's ills is a return to some previous age of mankind. But I do doubt that any solution is possible unless we think of ourselves in the context of living nature "Perhaps that suggests an answer to the question what a 'nature writer' is. He is not a sentimentalist who says that 'nature never did betray the heart that loved her.' Neither is he simply a scientist classifying animals or reporting on the behavior of birds just because certain facts can be ascertained. He is a writer whose subject is the natural context of human life, a man who tries to communicate his observations and his thoughts in the presence of nature as part of his attempt to make himself more aware of that context. 'Nature writing' is nothing really new. It has always existed in literature. But it has tended in the course of the last century to become specialized partly because so much writing that is not specifically 'nature writing' does not present the natural context at all; because so many novels and so many treatises describe man as an economic unit, a political unit, or as a member of some social class but not as a living creature surrounded by other living things." (Joseph Wood Krutch, "Some Unsentimental Confessions of a Nature Writer." New York Herald Tribune Book Review , 1952)

- Creative Nonfiction

- Defining Nonfiction Writing

- A Guide to All Types of Narration, With Examples

- What You Should Know About Travel Writing

- Notable Authors of the 19th Century

- Genres in Literature

- Top 5 Books about Social Protest

- Must Reads If You Like 'Walden'

- Great Summer Creative Writing Programs for High School Students

- Point of View in Grammar and Composition

- Ways of Defining Art

- Ralph Waldo Emerson: American Transcendentalist Writer and Speaker

- What Is a Synopsis and How Do You Write One?

- The Power and Pleasure of Metaphor

- What Literature Can Teach Us

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

Nature Writing is Survival Writing: On Rethinking a Genre

Michelle nijhuis thinks it’s time for some new perspectives.

If there were a contest for Most Hated Genre, nature writing would surely take top honors. Other candidates—romance, say—have their detractors, but are stoutly defended by both practitioners and fans. When it comes to nature writing, though, no one seems to hate container and contents more than nature writers themselves.

“‘Nature writing’ has become a cant phrase, branded and bandied out of any useful existence, and I would be glad to see its deletion from the current discourse,” the essayist Robert Macfarlane wrote in 2015. When David Gessner, in his book Sick of Nature , imagined a party attended by his fellow nature writers, he described a thoroughgoing dud: “As usual with this crowd, there’s a whole lot of listening and observing going on, not a lot of merriment.”

Critics, for their part, have dismissed the genre as a “solidly bourgeois form of escapism,” with nature writers indulging in a “literature of consolation” and “fiddling while the agrochemicals burn.” Nature writers and their work are variously portrayed, fairly and not, as misanthropic, condescending, and plain embarrassing. Joyce Carol Oates, in her essay “Against Nature,” enumerated nature writing’s “painfully limited set of responses” to its subject in scathing all caps: “REVERENCE, AWE, PIETY, MYSTICAL ONENESS.”

Oates, apparently, was not consoled.

The persistence of nature writing as a genre has more to do with publishers than with writers. Labels can usefully lash books together, giving each a better chance of staying afloat in a flooded marketplace, but they can also reinforce established stereotypes, limiting those who work within a genre and excluding those who fall outside its definition. As Oates suggested, there are countless ways to think and write about what we call “nature,” many of them urgent. But nature writing, as defined by publishers and historical precedent, ignores all but a few.

The nature-writing genre emerged in the late 1700s, during the peculiar moment when nature, as Europeans and North American intellectuals saw it, was no longer fearfully mysterious but not yet endangered. The scientific classification of species had brought some apparent order to undomesticated landscapes, allowing writers such as William Bartram, a botanist who traveled through the American South shortly before the Revolutionary War, to perceive not a tangle of flora and fauna but “an infinite variety of animated scenes, inexpressibly beautiful and pleasing.”

Such “appreciative aesthetic responses to a scientific view of nature,” as the writer and naturalist David Rains Wallace once described them, were products not only of their time and place but their culture and class. Scientific views of nature are not the only possible views, of course, and as many anthropologists and linguists have pointed out, the concept of “nature” as a collection of objects, separate from but subservient to humans, is also far from universal.

In the 19th century, many of the thinkers we now call nature writers took some exception to the genre’s original project. While Ralph Waldo Emerson famously saw human transcendence as the primary purpose of the non-human world, his rebellious protégé Henry David Thoreau was more interested in other forms of life for their own sake, and more willing to get his literal and metaphorical boots muddy. John Muir, though notoriously dismissive of the human history of the Sierra Nevada , had unusually egalitarian ideas about other species, considering even lizards, squirrels, and gnats to be fellow occupants of the planet.

As I learned while researching my book Beloved Beasts , a history of the modern conservation movement, the rise of the science of ecology in the early 20th century made it ever clearer that the boundaries between humans and “nature” were more linguistic and cultural than physical. Rachel Carson, who cited Thoreau as one of her primary influences, further expanded the nature-writing genre by tying the fate of other species to the fate of human bodies.

Any genre can only stretch so far, though, and the limitations of nature writing are inscribed in its very name. Nature writing still tends to treat its subject as “an infinite variety of animated scenes,” and while the genre’s membership and approaches have diversified somewhat in recent years, its prizewinners resemble its founders : mostly white, mostly male, and mostly from wealthy countries. The poet and essayist Kathleen Jamie calls them Lone Enraptured Males .

Meanwhile, writers in every genre and discipline are wrestling with the relationship between humans and the rest of life, recognizing that while writing about other species is often about wonder and uplift, it is also, inevitably, about survival—the survival of all species, including our own. Amitav Ghosh, whose novels often follow the connections among species and habitats—humans and snakes, tigers and dolphins, land and sea—recently published The Nutmeg’s Curse , his second book-length essay about the literature, history, and politics of climate change. (The first was The Great Derangement , published in 2016.)

Science-fiction writer Jeff VanderMeer returns again and again to the unstable boundaries between humans and other species, most recently in his novel Hummingbird Salamander . Margaret Atwood, a dedicated birdwatcher, wrote that the sight of red-necked crakes “scuttling about in the underbrush” in northern Australia inspired her dystopian MaddAddam trilogy . Historians such as Dina Gilio-Whitaker, the author of As Long as Grass Grows , and Nick Estes, the author of Our History Is The Future , document the damage done to Indigenous cultures and all species by centuries of capitalism and colonialism. These and many other works acknowledge that humans are both observers of and participants in the network of life on earth—and that our roles, while often destructive, can be constructive, too.

Today, the nature-writing genre reminds me of the climate-change beat in journalism: the stakes and scope of the job have magnified to the point that the label is arguably worse than useless, misrepresenting the work as narrower than it is and restricting its potential audience. The state of “nature,” like the state of the global climate, can no longer be appreciated from a distance, and its literature can no longer be confined to a single shelf. If we must give it a label, I say we call it survival writing. Or, better yet, writing.

__________________________________

Michelle Nijhuis’s book Beloved Beasts is available through W.W. Norton & Company. Copyright © 2022.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Michelle Nijhuis

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

Lit Hub Asks: 5 Authors, 7 Questions, No Wrong Answers

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

- Shopping Cart

Advanced Search

- Browse Our Shelves

- Best Sellers

- Digital Audiobooks

- Featured Titles

- New This Week

- Staff Recommended

- Suggestions for Kids

- Fiction Suggestions

- Nonfiction Suggestions

- Reading Lists

- Upcoming Events

- Ticketed Events

- Science Book Talks

- Past Events

- Video Archive

- Online Gift Codes

- University Clothing

- Goods & Gifts from Harvard Book Store

- Hours & Directions

- Newsletter Archive

- Frequent Buyer Program

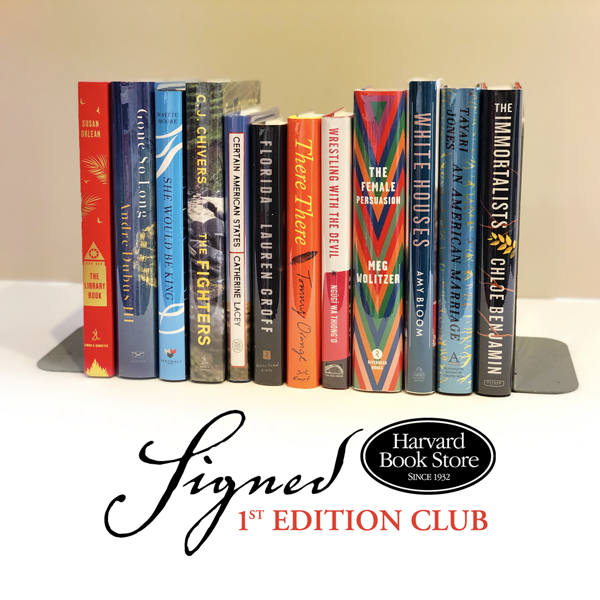

- Signed First Edition Club

- Signed New Voices in Fiction Club

- Harvard Square Book Circle

- Off-Site Book Sales

- Corporate & Special Sales

- Print on Demand

- All Our Shelves

- Academic New Arrivals

- New Hardcover - Biography

- New Hardcover - Fiction

- New Hardcover - Nonfiction

- New Titles - Paperback

- African American Studies

- Anthologies

- Anthropology / Archaeology

- Architecture

- Asia & The Pacific

- Astronomy / Geology

- Boston / Cambridge / New England

- Business & Management

- Career Guides

- Child Care / Childbirth / Adoption

- Children's Board Books

- Children's Picture Books

- Children's Activity Books

- Children's Beginning Readers

- Children's Middle Grade

- Children's Gift Books

- Children's Nonfiction

- Children's/Teen Graphic Novels

- Teen Nonfiction

- Young Adult

- Classical Studies

- Cognitive Science / Linguistics

- College Guides

- Cultural & Critical Theory

- Education - Higher Ed

- Environment / Sustainablity

- European History

- Exam Preps / Outlines

- Games & Hobbies

- Gender Studies / Gay & Lesbian

- Gift / Seasonal Books

- Globalization

- Graphic Novels

- Hardcover Classics

- Health / Fitness / Med Ref

- Islamic Studies

- Large Print

- Latin America / Caribbean

- Law & Legal Issues

- Literary Crit & Biography

- Local Economy

- Mathematics

- Media Studies

- Middle East

- Myths / Tales / Legends

- Native American

- Paperback Favorites

- Performing Arts / Acting

- Personal Finance

- Personal Growth

- Photography

- Physics / Chemistry

- Poetry Criticism

- Ref / English Lang Dict & Thes

- Ref / Foreign Lang Dict / Phrase

- Reference - General

- Religion - Christianity

- Religion - Comparative

- Religion - Eastern

- Romance & Erotica

- Science Fiction

- Short Introductions

- Technology, Culture & Media

- Theology / Religious Studies

- Travel Atlases & Maps

- Travel Lit / Adventure

- Urban Studies

- Wines And Spirits

- Women's Studies

- World History

- Writing Style And Publishing

The Best American Science and Nature Writing 2020

A collection of the best science and nature writing published in North America in 2019, guest edited by New York Times best-selling author and ground-breaking physicist Dr. Michio Kaku.

“Scientists and science writers have a monumental task: making science exciting and relevant to the average person, so that they care,” writes renowned American physicist Michio Kaku. “If we fail in this endeavor, then we must face dire consequences.” From the startlingly human abilities of AI, to the devastating accounts of California’s forest fires, to the impending traffic jam on the moon, the selections in this year’s Best American Science and Nature Writing explore the latest mysteries and marvels occurring in our labs and in nature. These gripping narratives masterfully translate the work of today’s brightest scientists, offering a clearer view of our world and making us care.

THE BEST AMERICAN SCIENCE AND NATURE WRITING 2020 INCLUDES RIVKA GALCHEN • ADAM GOPNIK • FERRIS JABR • JOSHUA SOKOL • MELINDA WENNER MOYER • SIDDHARTHA MUKHERJEE • NATALIE WOLCHOVER and others

There are no customer reviews for this item yet.

Classic Totes

Tote bags and pouches in a variety of styles, sizes, and designs , plus mugs, bookmarks, and more!

Shipping & Pickup

We ship anywhere in the U.S. and orders of $75+ ship free via media mail!

Noteworthy Signed Books: Join the Club!

Join our Signed First Edition Club (or give a gift subscription) for a signed book of great literary merit, delivered to you monthly.

Harvard Square's Independent Bookstore

© 2024 Harvard Book Store All rights reserved

Contact Harvard Book Store 1256 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138

Tel (617) 661-1515 Toll Free (800) 542-READ Email [email protected]

View our current hours »

Join our bookselling team »

We plan to remain closed to the public for two weeks, through Saturday, March 28 While our doors are closed, we plan to staff our phones, email, and harvard.com web order services from 10am to 6pm daily.

Store Hours Monday - Saturday: 9am - 11pm Sunday: 10am - 10pm

Holiday Hours 12/24: 9am - 7pm 12/25: closed 12/31: 9am - 9pm 1/1: 12pm - 11pm All other hours as usual.

Map Find Harvard Book Store »

Online Customer Service Shipping » Online Returns » Privacy Policy »

Harvard University harvard.edu »

- Clubs & Services

Nature Writing

Master of Arts, Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing

Master of Arts, Master of Fine Arts

Graduate Program in Creative Writing

Our Nature Writing concentration seeks to empower writers who care about the urgent and wonder-filled world of contemporary environmental literature. We are founded on the core belief that writing can be an agent of change, that creativity engenders solutions, and that students should be individually mentored to achieve their highest artistic goals. We welcome and mentor all genres.

Program Overview

Use your passion as a force for positive change

Western’s MFA and M.A. in Nature Writing offers an ethically-alert, cutting-edge program which explores essential topics in the field of contemporary ecological writing, including climate chaos and environmental justice. While students focus on their genre of choice, major subgenres are explored in both traditional and experimental forms.

Because the Nature Writing concentration offers both an MFA and an M.A., you’ll be able to choose a degree that best meets your personal and career goals, setting you up for professional success after graduation.

A diverse and rigorous curriculum includes zoom classes and asynchronous discussions, making the program flexible and convenient. Faculty and guest speakers are widely published and are dedicated teachers and mentors.

Students come from diverse disciplines and backgrounds, and we encourage any writers engaged in the intersection of art, ecology, and stewardship.

Graduates leave the program with a book-length manuscript, short-form work, and a thorough understanding of the many approaches to writing about our place, our planet, and our people.

Inspired by our surroundings

Nature Writing students and faculty enjoy a walk together during each summer residency to enjoy the breathtaking landscape of the Gunnison Valley.

- Program Requirements

At Western, course rotations are crafted to encompass a variety of subject fields for a comprehensive education and versatile degree. For required courses and degree plans, visit the official University Catalog . Below is a general overview of courses at Western Colorado University related to this area of study.

The Graduate Program in Creative Writing offers an MFA in Genre Fiction, Nature Writing, Poetry, or Screenwriting. Western's curricula differs from other low-residency programs by emphasizing intense training in craft, building of a writing community, close study of historically underrepresented writers, and exposure to the business of being a writer.

All programs require a high degree of commitment and excellence from candidates, who must maintain at least a 3.00 course average to complete the program. A minimum grade of B- in each course is required.

In all three summer semesters, MFA candidates complete a 3-credit intensive course in their concentrations. In their first summer, they take a first-year intensive course and also complete two credits of CRWR 600, The Common Read & Writing Craft. In their second summer, they take a second-year intensive course and also earn two credits for starting their thesis project. In their third summer, they take a final intensive course, plus a 1-credit elective which allows them to explore other concentrations.

During the Fall and Spring semesters of their first year, full-time students take two 6-credit courses for a total of 12 credits per semester. Students may anticipate spending between 25 and 30 hours per week on assigned coursework. The coursework typically consists of readings and viewings, asynchronous discussions, and writing assignments for which instructors offer online feedback. Students also participate regularly in live virtual classes and one-on-one meetings with faculty.