The Federalist Papers

Welcome. This is where you learn about the Federalist Papers.

Dennis grover interviews mary webster, modern english translation of the federalist papers explains how the us constitution blocks the abuse of power, blocks growth of tyranny, and defends individual rights..

How The Federalist Papers Saved My Life and They Will Help Save the Country

Check out my 10th-grade reading-level translation of Federalist Paper Number 1.

The Federalist Papers Explains Federal Powers

Introduction to.

Outline of all 85

Federalist Papers

Federalist Paper # 1

original text

modern English translation

Introducing your hostess on this inspiring journey.

My qualifications to teach the U.S. Constitution

Federalist Papers: Translation v. Original Text

Federalist Papers Explain How to Become a Tyrant

Introduction to Annotated Constitution

Laws, Regulations, and Tyranny

Federal Property

Amendment One v. The Johnson Amendment

Presidential Appointments

Advice and Consent

Bruce Walker cartoons

Political cartoons, central coast humane society cartoons.

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 3

- The Articles of Confederation

- What was the Articles of Confederation?

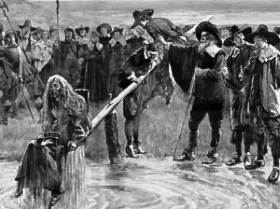

- Shays's Rebellion

- The Constitutional Convention

- The US Constitution

The Federalist Papers

- The Bill of Rights

- Social consequences of revolutionary ideals

- The presidency of George Washington

- Why was George Washington the first president?

- The presidency of John Adams

- Regional attitudes about slavery, 1754-1800

- Continuity and change in American society, 1754-1800

- Creating a nation

- The Federalist Papers was a collection of essays written by John Jay, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton in 1788.

- The essays urged the ratification of the United States Constitution, which had been debated and drafted at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787.

- The Federalist Papers is considered one of the most significant American contributions to the field of political philosophy and theory and is still widely considered to be the most authoritative source for determining the original intent of the framers of the US Constitution.

The Articles of Confederation and Constitutional Convention

- In Federalist No. 10 , Madison reflects on how to prevent rule by majority faction and advocates the expansion of the United States into a large, commercial republic.

- In Federalist No. 39 and Federalist 51 , Madison seeks to “lay a due foundation for that separate and distinct exercise of the different powers of government, which to a certain extent is admitted on all hands to be essential to the preservation of liberty,” emphasizing the need for checks and balances through the separation of powers into three branches of the federal government and the division of powers between the federal government and the states. 4

- In Federalist No. 84 , Hamilton advances the case against the Bill of Rights, expressing the fear that explicitly enumerated rights could too easily be construed as comprising the only rights to which American citizens were entitled.

What do you think?

- For more on Shays’s Rebellion, see Leonard L. Richards, Shays’s Rebellion: The American Revolution’s Final Battle (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002).

- Bernard Bailyn, ed. The Debate on the Constitution: Federalist and Anti-Federalist Speeches, Articles, and Letters During the Struggle over Ratification; Part One, September 1787 – February 1788 (New York: Penguin Books, 1993).

- See Federalist No. 1 .

- See Federalist No. 51 .

- For more, see Michael Meyerson, Liberty’s Blueprint: How Madison and Hamilton Wrote the Federalist Papers, Defined the Constitution, and Made Democracy Safe for the World (New York: Basic Books, 2008).

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Federalist Papers

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 22, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

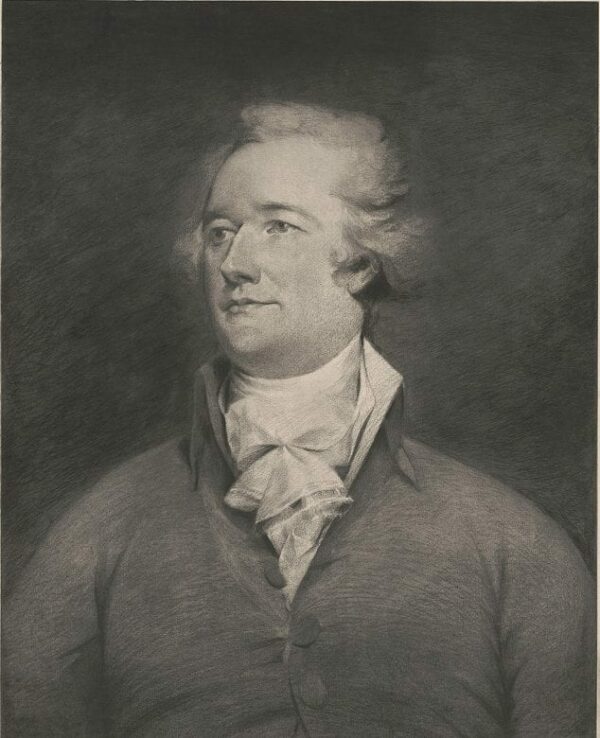

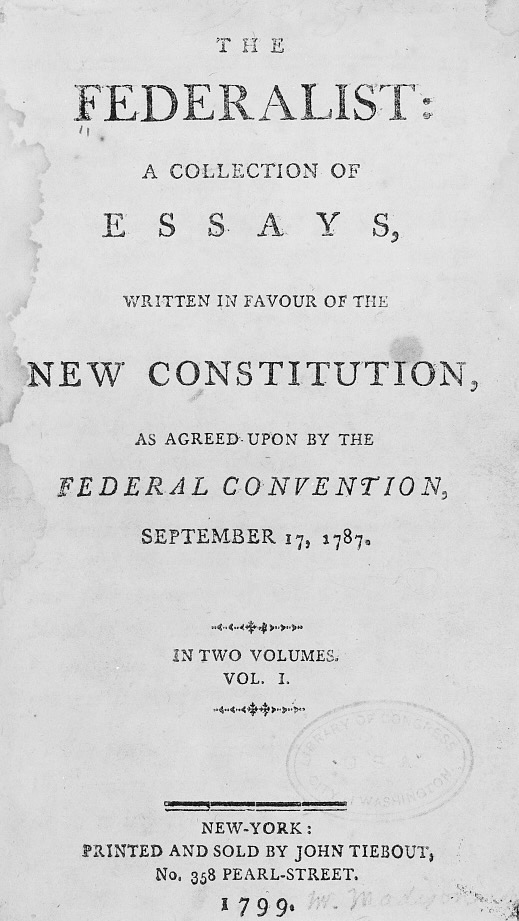

The Federalist Papers are a collection of essays written in the 1780s in support of the proposed U.S. Constitution and the strong federal government it advocated. In October 1787, the first in a series of 85 essays arguing for ratification of the Constitution appeared in the Independent Journal , under the pseudonym “Publius.” Addressed to “The People of the State of New York,” the essays were actually written by the statesmen Alexander Hamilton , James Madison and John Jay . They would be published serially from 1787-88 in several New York newspapers. The first 77 essays, including Madison’s famous Federalist 10 and Federalist 51 , appeared in book form in 1788. Titled The Federalist , it has been hailed as one of the most important political documents in U.S. history.

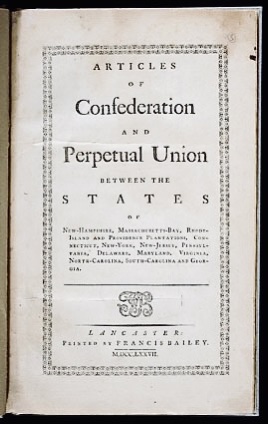

Articles of Confederation

As the first written constitution of the newly independent United States, the Articles of Confederation nominally granted Congress the power to conduct foreign policy, maintain armed forces and coin money.

But in practice, this centralized government body had little authority over the individual states, including no power to levy taxes or regulate commerce, which hampered the new nation’s ability to pay its outstanding debts from the Revolutionary War .

In May 1787, 55 delegates gathered in Philadelphia to address the deficiencies of the Articles of Confederation and the problems that had arisen from this weakened central government.

A New Constitution

The document that emerged from the Constitutional Convention went far beyond amending the Articles, however. Instead, it established an entirely new system, including a robust central government divided into legislative , executive and judicial branches.

As soon as 39 delegates signed the proposed Constitution in September 1787, the document went to the states for ratification, igniting a furious debate between “Federalists,” who favored ratification of the Constitution as written, and “Antifederalists,” who opposed the Constitution and resisted giving stronger powers to the national government.

The Rise of Publius

In New York, opposition to the Constitution was particularly strong, and ratification was seen as particularly important. Immediately after the document was adopted, Antifederalists began publishing articles in the press criticizing it.

They argued that the document gave Congress excessive powers and that it could lead to the American people losing the hard-won liberties they had fought for and won in the Revolution.

In response to such critiques, the New York lawyer and statesman Alexander Hamilton, who had served as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention, decided to write a comprehensive series of essays defending the Constitution, and promoting its ratification.

Who Wrote the Federalist Papers?

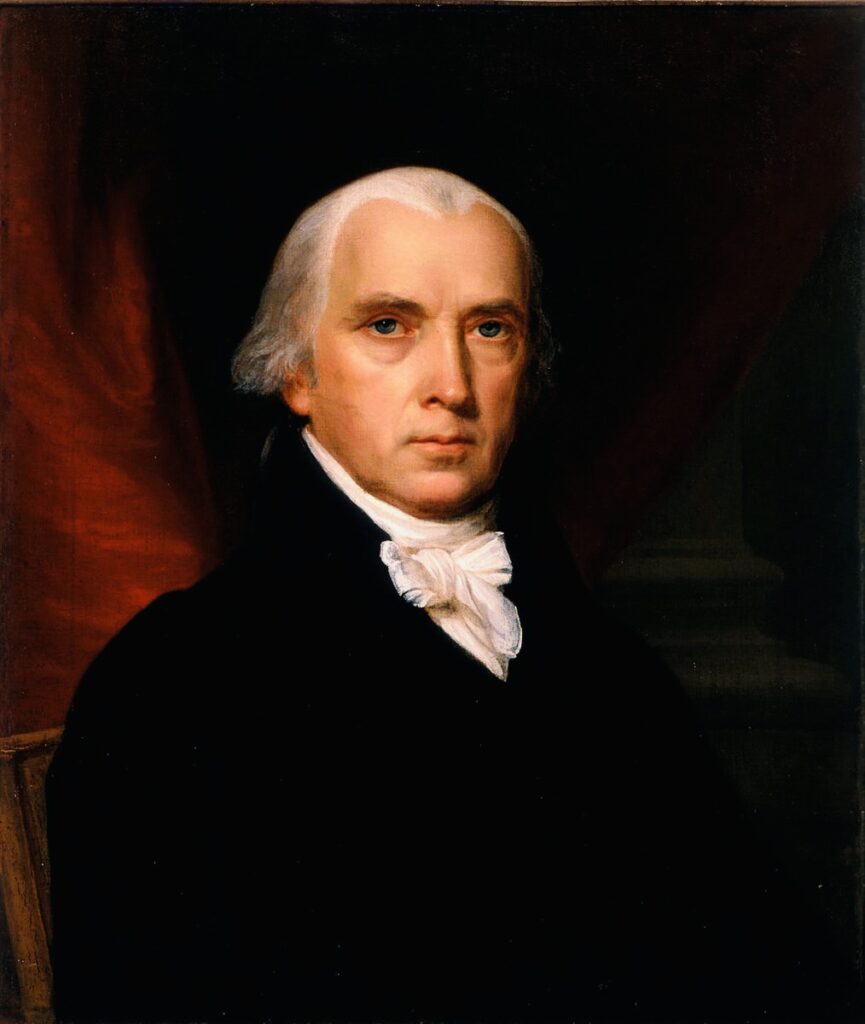

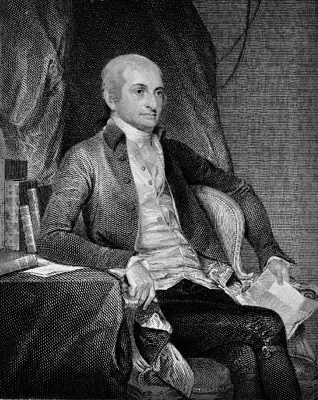

As a collaborator, Hamilton recruited his fellow New Yorker John Jay, who had helped negotiate the treaty ending the war with Britain and served as secretary of foreign affairs under the Articles of Confederation. The two later enlisted the help of James Madison, another delegate to the Constitutional Convention who was in New York at the time serving in the Confederation Congress.

To avoid opening himself and Madison to charges of betraying the Convention’s confidentiality, Hamilton chose the pen name “Publius,” after a general who had helped found the Roman Republic. He wrote the first essay, which appeared in the Independent Journal, on October 27, 1787.

In it, Hamilton argued that the debate facing the nation was not only over ratification of the proposed Constitution, but over the question of “whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force.”

After writing the next four essays on the failures of the Articles of Confederation in the realm of foreign affairs, Jay had to drop out of the project due to an attack of rheumatism; he would write only one more essay in the series. Madison wrote a total of 29 essays, while Hamilton wrote a staggering 51.

Federalist Papers Summary

In the Federalist Papers, Hamilton, Jay and Madison argued that the decentralization of power that existed under the Articles of Confederation prevented the new nation from becoming strong enough to compete on the world stage or to quell internal insurrections such as Shays’s Rebellion .

In addition to laying out the many ways in which they believed the Articles of Confederation didn’t work, Hamilton, Jay and Madison used the Federalist essays to explain key provisions of the proposed Constitution, as well as the nature of the republican form of government.

'Federalist 10'

In Federalist 10 , which became the most influential of all the essays, Madison argued against the French political philosopher Montesquieu ’s assertion that true democracy—including Montesquieu’s concept of the separation of powers—was feasible only for small states.

A larger republic, Madison suggested, could more easily balance the competing interests of the different factions or groups (or political parties ) within it. “Extend the sphere, and you take in a greater variety of parties and interests,” he wrote. “[Y]ou make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens[.]”

After emphasizing the central government’s weakness in law enforcement under the Articles of Confederation in Federalist 21-22 , Hamilton dove into a comprehensive defense of the proposed Constitution in the next 14 essays, devoting seven of them to the importance of the government’s power of taxation.

Madison followed with 20 essays devoted to the structure of the new government, including the need for checks and balances between the different powers.

'Federalist 51'

“If men were angels, no government would be necessary,” Madison wrote memorably in Federalist 51 . “If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary.”

After Jay contributed one more essay on the powers of the Senate , Hamilton concluded the Federalist essays with 21 installments exploring the powers held by the three branches of government—legislative, executive and judiciary.

Impact of the Federalist Papers

Despite their outsized influence in the years to come, and their importance today as touchstones for understanding the Constitution and the founding principles of the U.S. government, the essays published as The Federalist in 1788 saw limited circulation outside of New York at the time they were written. They also fell short of convincing many New York voters, who sent far more Antifederalists than Federalists to the state ratification convention.

Still, in July 1788, a slim majority of New York delegates voted in favor of the Constitution, on the condition that amendments would be added securing certain additional rights. Though Hamilton had opposed this (writing in Federalist 84 that such a bill was unnecessary and could even be harmful) Madison himself would draft the Bill of Rights in 1789, while serving as a representative in the nation’s first Congress.

HISTORY Vault: The American Revolution

Stream American Revolution documentaries and your favorite HISTORY series, commercial-free.

Ron Chernow, Hamilton (Penguin, 2004). Pauline Maier, Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788 (Simon & Schuster, 2010). “If Men Were Angels: Teaching the Constitution with the Federalist Papers.” Constitutional Rights Foundation . Dan T. Coenen, “Fifteen Curious Facts About the Federalist Papers.” University of Georgia School of Law , April 1, 2007.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Federalist Papers

- Federalist 1-10

- Federalist 11-36

- Federalist 37-61

- Federalist 62-85

- America's Four Republics

- Article The First

- Feds Finally Agree

- Historic.us

Monday, December 17, 2012

Alexander hamilton - john jay - james madison.

Students and Teachers of US History this is a video of Stanley and Christopher Klos presenting America's Four United Republics Curriculum at the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School. The December 2015 video was an impromptu capture by a member of the audience of Penn students, professors and guests that numbered about 200. - Click Here for more information

The Constitutionalist

The politics of constitutions.

Can We Teach the “Federalist Papers” Today?

Steven B. Smith is the Alfred Cowles Professor of Political Science at Yale University .

Over the years I have taught the Federalist Papers more times than I can count and it has always been a challenge. This is not due to the inherent difficulty of the text, although its language and arguments are often demanding, but because students believe they already know what the book is about before they even open it. They know, perhaps, that it contains eighty-five articles written by James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay – known collectively as Publius — designed to persuade the ratifying convention of New York state to support the new Constitution. But what they don’t know and it seems increasingly difficult to convey is the truly revolutionary nature of the book itself. Far from being simply an occasional document written for the limited purposes of securing ratification of the new Constitution, the Federalist Papers initiated nothing less than a revolution in political thought.

The Federalist Papers changed our understanding of government in three decisive ways. First, it offered a defense of what was truly a first in political history, namely, a written Constitution. The closest model to our own, the British constitution, consisted of the ancient body of common law stretching back to the Norman Conquest but not something codified in a single document or text. Today, of course, written constitutions are the norm but in the eighteenth-century this was unheard of.

It is the very ubiquity of written constitutions that has over shadowed the uniqueness of the Federalist’s achievement. As these constitutions have proliferated, so too have their claims. The Soviet Constitution of 1936 enumerated a basket of economic rights not found in the Western democracies. The UN Charter of 1945 promised certain social and cultural rights previously unknown in history. And the EU Constitution – all 235 pages of it – comprises a contradictory bundle of claims on behalf of social justice, universal health care, and full employment that go far beyond any country’s capacity. There is an ever-widening gap between what these constitutions promise and the political reality they profess to describe.

Second, Publius fundamentally redefined what it meant to be (or to have) a republican form of government. In the past, republics were deemed possible only in small rustic outposts like Switzerland or the city-states of northern Italy. The Constitution’s opponents repeatedly cited the authority of Montesquieu’s Spirit of the Laws to argue that a vast territory of the kind imagined by the framers would inevitably slide into monarchy or even despotism. In a large state, the center of government must of necessity be distant and removed from the people it is supposed to represent.

Furthermore, there was the assumption that any people who were to govern themselves must be relatively homogenous in terms of their manners, habits, and customs. A republic is not only a set of institutions but represents an ethos, a shared way of life, that is only possible among people with common moral habits and dispositions. Large states produce luxury , a term that for much of the eighteenth-century was synonymous with inequality and corruption. Only small states were likely to produce a society where there were no extremes of wealth, influence, or education, that produced the kind of moderation – some would call it mediocrity — necessary for a simple, sturdy, and virtuous people. The small republic was regarded as a school of citizenship as much as a plan for government.

The Federalist authors completely overturned these previous assumptions. They were the first to propose a large extended republic composed of diverse factions and interests with representative institutions designed to create the requisite checks and balances on power. This was nothing short of a new definition of republicanism that had no previous model to which it might refer. This idea of a republic extensive enough to ensure the multiplicity of competing interests found in large states but without the disadvantages of the concentration of power into the hands of a distant ruler was a first in the history of political theory. This has rightly been called the “Madisonian Moment.”

From its beginnings, the Madisonian republic was to be an unabashedly bourgeois republic based upon the rights of property and the protection of individual liberty. The task of government would not impose impossibly high standards of justice and morality – the ends, for example, of Plato’s Republic — but control the dangers of faction and conflict arising from the diversity of different kinds of property. The task of statesmanship in the modern commercial republic would not be to abolish or eliminate factions but to manage the differences between them. “The regulation of these various and interfering interests,” Madison wrote in Federalist #10 , “forms the principal task of modern legislation.”

This in turn led to the third great innovation proposed by the Federalist , namely, the principle of representation. According to Hamilton, the principle of representation – along with checks and balances and judicial tenure for good behavior — marks one of the great discoveries of modern political science. This led in turn to a distinction between democracies that were based on the direct rule of the people and republics that were governed indirectly through representatives. Democracies, Madison wrote, have “ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention, have ever been found incompatible with personal security or the rights of property.” The purpose of representation, by contrast, was “to refine and enlarge the public views by passing them through the medium of a chosen body of citizens.” Representation would act like the process of smelting where the gold is extracted from the dross.

The question of exactly who could represent whom was the explicit theme of Federalist #35 . Building on Madison’s sociology of different kinds of property, Hamilton divided society into two broad economic classes that he describes as the interests of the manufacturers and the mechanics on the one side and the interests of land-owners on the other. The mechanics and manufacturers, he says, will find their natural patron in the wealthy merchant just as the various land owners will find their patron in the wealthier landlords. Standing between these two will be the group that Hamilton believes to be their “natural arbiter,” namely those of “the learned professions,” who through education and enlightenment will have a broader and more impartial grasp of the whole. By the learned professions, Hamilton meant mainly lawyers. It would be through their talents and demonstrated abilities that this class will attract the “sympathy” of its constituents. This passage expressed Hamilton’s hope – at best only partially realized — for reconciling popular government with something like liberal education.

The Federalist Papers have been remarkably successful in defining the terms of modern republican government. They instituted nothing short of a conceptual revolution in political thought. A republic – or what we call democracy today — has become largely what Publius said it was. And yet many today are extremely disaffected with the representative republic. It has long been a complaint that our representative institutions are remote and unresponsive. Some even believe that we are experiencing a crisis of representation that requires new forms of direct political participation. Experiments with mini-publics, crowdsourcing techniques, and sortition are some of the more extreme solutions being offered.

The critique of the Federalist Papers comes today mainly from two sources. Those on the left complain that the commercial republic favors the interests of the wealthy and does not do enough to redistribute wealth downwards. They have a point. The Federalist authors did not aim to eliminate classes and redistribute wealth. Publius’s goal was not to abolish classes but to represent them. The American founding was both more modest and more successful than later revolutions – the French, the Russian – that claimed to remake society from the ground up. The American founders rejected not only ancient egalitarianism represented by Sparta but also implicitly later experiments in socialism. The Marxist critique of the American founding was correct. It aimed only at a political revolution, not a social one. It is difficult in today’s environment to show how Publius’s goal was actually an act of heroic self-restraint that they hoped would be a guide to future statesmen.

Critics on the right have complained that the Madisonian republic is not sufficiently attentive to the claims of civic virtue – the forms of “social capital” – that make for a healthy moral climate. No regime, especially a republic, can afford to be indifferent to the character of its citizens. The problem facing the Madisonian republic is whether there remained any room left for such traditional republican themes as equality, virtue, and the common good. There is an almost complete silence about religion and religious education in the Federalist which was then (and probably still remains) the primary source of moral instruction for most people. Was this an oversight? It seems likely that the Federalist authors simply took for granted that religious education would remain the primary form of instruction, but this is certainly no longer the case today. It begs the question of whether a republican form of government can be sustained on the principles of individualism and the pursuit of interest that are at the core of modern capitalist economic systems?

The question is whether teaching the Federalist Papers can be rescued today. Students are more likely to be attuned to the failings of the American founders than by their success. The fact that many of the Constitution’s signers were slave owners and the document itself is silent on slavery will be taken as evidence of a malign intent. Recent attempts by scholars to put the American founding in a “global” context have the effect of diminishing the sheer novelty and iconoclasm of the founding moment. Perhaps most tellingly, the virtues of a bourgeois republic – honesty, compromise, tolerance, and fair-dealing – seem pale in comparison to the demands for social justice here and now. As a student of mine once said, “I need something to help me get up in the morning.”

There is no simple answer to these objections except to return again and again to the text. If, however, the defense of the bourgeois democratic order against a rising wave of autocracy is not enough to get one out of bed, I don’t know what is.

Share Our Content

15 thoughts on “ can we teach the “federalist papers” today ”.

- Pingback: Can We Teach the “Federalist Papers” Today? - The Investing Box

- Pingback: Can We Teach the “Federalist Papers” Today? - United Push Back

- Pingback: Can We Teach the “Federalist Papers” Today?

- Pingback: Can We Teach the “Federalist Papers” Today? – Investings Keeper

- Pingback: Can We Teach the “Federalist Papers” Today? – Beneficial Investment Now – Investing and Stock News

- Pingback: Can We Teach the “Federalist Papers” Today? – MAGAtoon

- Pingback: Can We Teach the “Federalist Papers” Today? – Gnews Amrita Bazar

- Pingback: Can We Teach the “Federalist Papers” Today? – CFO News Hubb

- Pingback: Can We Teach the “Federalist Papers” Today? – GOP MAGA

Maybe we should teach the Anti-Federalist Papers. A coup d’etat that gave us the 16th Amendment, the Federal Reserve Act and an empire. No thanks. Of course, I do understand that we got exactly what we deserve based upon our level of rational thinking.

- Pingback: Can We Educate the “Federalist Papers” At this time? - BuyInsuranceGroup.com

- Pingback: Can We Teach the “Federalist Papers” Today? – Amrita Bazar IG News

- Pingback: Can We Teach the “Federalist Papers” Today? - Investment Policy Wealth

- Pingback: US CONSTITUTION - Essay-prime

- Pingback: US CONSTITUTION - Qualified-writers

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Discover more from the constitutionalist.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Oxford University Press's Academic Insights for the Thinking World

The Federalist Papers: America Then and Now

- October 23 rd 2008

Recently published in the new-look Oxford World’s Classics series is an edition of The Federalist Papers , which has been edited by Lawrence Goldman . Lawrence is Tutorial Fellow of Modern History at St Peter’s College, Oxford , and has been the editor of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography since 2004. In the post below, Lawrence talks about how reading The Federalist Papers helps our understanding of present-day America.

The Federalist Papers comprise 85 essays published in the New York city press in the winter of 1787-88 and were written by three of the most eminent of the founding fathers of the republic: Alexander Hamilton , aide-de-camp to George Washington during the Revolutionary War and the first Secretary of the US Treasury; James Madison , the fourth president of the United States and the most influential figure in the drafting of the US Constitution in 1787; and John Jay , a leading American diplomat during the Revolution and the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. These three, all of them ‘federalists’, or supporters of the projected federal union of individual states to form the United States, came together to commend the Constitution to the people of New York in articles published every 2-3 days over several months.

During the War of Independence the thirteen former British colonies had been held together by a very weak form of national government. By the mid-1780s many Americans believed that this was no longer sufficient to meet the new challenges of nation and state formation. Through the summer of 1787 a federal Constitution was drafted at a convention of all the states in Philadelphia; it then had to be ratified by popularly-elected assemblies in each state. When 9 of 13 states had so ratified it, the Constitution would become operative and the United States created.

The state of New York – large, wealthy and populous – was crucial to the federalist design, but there was considerable opposition to joining the Union there, in a state which had fared well since independence from Britain in 1776 and in which many citizens wanted to ‘go it alone’. Hence the need to persuade the people by publishing these essays which explained and defended the draft Constitution and the need to form an American Union.

The Federalist Papers are thus a detailed account and analysis of the new Constitution, but are more than just an operational manual on how the projected federal government would work. They are also fluent philosophical discussions of the nature and purposes of government which have an important place in the development of western political thought and which may help us understand enduring American values and national character.

A first feature of the Federalist Papers is a sense of the vulnerability of the American experiment in self-government which the essays impart. The authors, reflecting their age, were critically aware of the threats to the republic they hoped to create. Some of those threats were internal, including social disorder on the one hand and the threat of tyranny on the other. Others were external, including the very real possibility that Great Britain or another of the European colonial powers might try to re-conquer the North American continent. Hence the need to form a ‘more perfect union’ with the internal strength and centralised control required to deter future aggression and defend the novelty of popular government. It could be argued that America’s peculiar sensitivity to threats of this nature, whether of internal subversion such as during the McCarthyite era, or of external aggression from nations and cultures hostile to the American way of life, as also during the Cold War, dates from the historical experience of the 1780s and is enshrined in the discussion in the Federalist Papers. In Europe it is now customary to think Americans rather too quick to imagine themselves beset by enemies and thus too ready to adopt aggressive or threatening policies. A reading of the Federalist Papers suggests that concern over the vulnerability of the American republic has been an aspect of an enduring national perspective.

A second enduring aspect of these essays is the counterpoint in the American mind between idealism and realism. The Federalist Papers display both of the American behavioural archetypes so beloved of modern commentaries on the United States and its people. On the one hand there is an element of the utopian about them as the authors commend to their readers an entirely innovative form of government unlike any elsewhere on the globe. They capture the optimism and enthusiasm of the American spirit. On the other hand, the psychological foundations of the essays are intensely realistic and pragmatic: the authors also adopt an unflattering view of human nature which is frequently presented as avaricious, factional, and selfish, and for that reason needs to be controlled and directed by a stronger central government than had existed hitherto among the newly-independent states. Men are sometimes angels but are more often not: for that reason they need the guiding hand of a central government.

What follows from this is another revealing tension between a republic of virtue and a republic of laws. Hitherto in human history, as the Federalist Papers make clear, it had been accepted that self-government in a republic required, above all, individual and public virtue: if men and women were morally good in themselves and careful for the civic good as well, they might be able to govern themselves; if not, republics must fall. But what happens to this traditional view of republicanism if, in reality, men and women are self-interested and lack moral sense? The answer provided in the Federalist Papers is to build a system of government on laws rather than on virtue; the enduring American faith in their constitution and constitutionalism in general is related to this fear that left to themselves the people would descend into disorder and conflict, and there seemed to be evidence of this in the states in the 1780s after independence had been secured. In the view of the Federalist Papers, if men and women are not naturally virtuous they can be constrained to be so by a shared obedience to laws – laws made by the people for their own welfare.

In line with the belief that republics depended on virtue, conventional theories of republicanism from the ancient Greek philosophers to Rousseau held that republics had to be homogeneous and also of small extent so that all the population shared the same basic interests. But in perhaps the most famous of the essays, number 10, written by James Madison, he overturned this classical view and made the case for a plurality of interests in a large and extensive republic, the kind of society the proposed United States was to become. As Madison argued his case, if the major threat to popular self-government came from the potential development of a tyranny, the antidote to this was a plethora of social interests in competition with each other. In such a situation no single interest could come to dominate the new United States; instead, there would be many different groups constantly jockeying for position and influence. And it followed that the larger the republic and the more diverse the population, the greater the range of interests and the smaller the threat from any single one of them.

In this way Madison famously defended the proposed United States from the attacks of so-called Antifederalists: their fear that the new government might become an authoritarian one could be countered by pointing to the benefits of pluralism. Thus the Federalist Papers point us beyond the age of the Revolution towards the modern liberalism of the United States in a society encompassing a plethora of groups and interests which compete freely for resources, influence, and prominence.

In conclusion, while we must treat the Federalist Papers as an expression of the values, ideas and psychology of the men who made the American Revolution, they give us clues towards an understanding of some of the pervasive attitudes and features of contemporary American life. In a society still governed by the Constitution of 1787 the assumptions of that age must inevitably shape the nature of the American present, and some of those enduring assumptions may be found in the Federalist Papers.

- Oxford World's Classics

Our Privacy Policy sets out how Oxford University Press handles your personal information, and your rights to object to your personal information being used for marketing to you or being processed as part of our business activities.

We will only use your personal information to register you for OUPblog articles.

Or subscribe to articles in the subject area by email or RSS

Related posts:

Recent Comments

[…] as paradigmatic statements of the general theory of the Constitution. Some time ago on OUPblog, Lawrence Goldman explained how reading The Federalist Papers can further an understanding of present-day […]

[…] legacy in development of modern western political thought. And, closer to home, they illuminate two important aspects of the American experiment: the sheer vulnerability of self-government; and what Oxford University’s Lawrence Goldman calls, […]

Comments are closed.

Navigation menu

Personal tools.

- View source

- View history

- Encyclopedia Home

- Alphabetical List of Entries

- Topical List

- What links here

- Related changes

- Special pages

- Printable version

- Permanent link

- Page information

The Federalist Papers

The Federalist Papers originated as a series of articles in a New York newspaper in 1787–88. Published anonymously under the pen name of “Publius,” they were written primarily for instrumental political purposes: to promote ratification of the Constitution and defend it against its critics.

Initiated by Alexander Hamilton , the series came to eighty-five articles, the majority by Hamilton himself, twenty-six by James Madison , and five by John Jay. The Federalist was the title under which Hamilton collected the papers for publication as a book.

Despite their polemical origin, the papers are widely viewed as the best work of political philosophy produced in the United States, and as the best expositions of the Constitution to be found amidst all the ratification debates. They are frequently cited for discerning the meaning of the Constitution and the intentions of the founders, although Hamilton’s papers are not always reliable as an exposition of his views: in The Federalist , Hamilton took care to avoid coming out clearly with his views on either the inadequacies of the Constitution or the potentiality for using it dynamically. Instead, he expressed himself indirectly, arguing that the only real danger would arise from the potential weaknesses of the central government under the Constitution , not from its potentialities for greater strength as charged by its opponents. Despite this, The Federalist can be and frequently has been referred to for its exposition of Hamilton’s position on executive authority, judicial review, and other institutional aspects of the Constitution.

The Federalist Papers are also admired abroad—sometimes more than in the United States. Hamilton is held in high esteem abroad: while in America his realist style is received with suspicion of undemocratic intentions, abroad it is taken as a reassurance of solidity, and it is the Jeffersonian idealist style that is received with suspicion of hidden intentions. The Federalist Papers are studied by jurists and legal scholars and cited for writing other countries’ constitutions. In this capacity they have played a significant role in the spread of federal, democratic, and constitutional governments around the world.

- 1 MODERN FEDERATION AS EXPOUNDED BY THE FEDERALIST

- 2 AMBIGUITIES OF COORDINATE FEDERALISM IN THE FEDERALIST

- 3 USE AND ABUSE OF THE FEDERALIST

- 4.1 Ira Straus

MODERN FEDERATION AS EXPOUNDED BY THE FEDERALIST

The Federalist Papers defended a new form of federalism : what it called “federation” as differentiated from “confederation.” There were precursors for this usage; The Federalist Papers solidified it. All subsequent federalism has been influenced by the example of “federation” in the United States; indeed, the success of it in the United States has led to its being known as “modern federation” in contrast to “classical confederation.” In its basic structures and principles, it has served as the model for most subsequent federal unions, as well as for the reform of older confederacies such as Switzerland.

The main distinguishing characteristics of the model of modern federation, elucidated and defended by The Federalist Papers , are as follows:

1. The federal government’s most important figures, the legislative, are elected largely by the individual citizens, rather than being primarily selected by the governments of member states as in confederation.

2. Conversely, federal law applies directly to individuals, through federal courts and agencies, rather than to member states as in confederation.

3. State citizens become also federal citizens, and naturalization criteria are established federally.

4. The federal Constitution and federal laws and treaties are the supreme law of the land, over and above state constitutions and laws.

5. Federal powers are enumerated, along with what came to be called an “Elastic Clause” (the authority to take measures “necessary and proper” for implementing its enumerated powers); the states keep the vast range of “reserved” powers, that is, the unspecified generality of other potential governmental powers. States cannot act where the federal government is assigned exclusive competence, nor where preempted by lawful federal action; they are specifically excluded from independent foreign relations, from maintaining an army or navy, from interfering with money, and from disrupting contracts or imposing tariffs.

6. Federal and state laws operate in parallel or as “coordinate” powers, each applying directly to individual citizens, rather than acting primarily through or with dependence on one another.

This “coordinate” method applies only to the “vertical” division of powers between federal and state governments, not to the “horizontal” or “functional” division of federal powers into executive, legislative, and judicial branches. The latter “separation of powers” is made in such a form as to deliberately keep the three branches mutually dependent on one another, so that no one of them can step forth—excepting the executive in emergencies—as a full-fledged authority on its own. This mutual functional dependence within the federal level is considered an assurance of steadiness of the rule of law and lack of arbitrariness; by contrast, obstructionism was feared if there were to remain a relation of dependence upon a vertically separate level of government. Thus the turn to “coordinate” powers, with federal and state operations proceeding autonomously from one another, or what came to be called “coordinate federalism.” This terminology encapsulated the departure from the old confederalism, in which federal government operations had been heavily dependent on the states.

AMBIGUITIES OF COORDINATE FEDERALISM IN THE FEDERALIST

Despite The Federalist ’s strong preference for coordinate powers, there are important deviations from it. For example, there are “concurrent” or overlapping powers, such as taxation. This, Hamilton says in The Federalist No. 32, necessarily follows from “the division of sovereign power”: each level of government needs it in order to function with “full vigor” on its own (thus allowing the celebratory formulation for American federalism, “strong States and a strong Federal Government”). Coordinate federalism requires, it turns out, some concurrent powers, not just coordinate powers.

In practice, the deviations from the “coordinate” theory go farther still. For the militia, the state governments have the competence to appoint all the officers and to conduct the training most of the time, but the federal government is authorized to regulate the training and discipline, as well as to place the militia when needed under federal command (a provision defended by Hamilton in The Federalist No. 29). For commercial law, the states draw up the detailed codes, but the federal power to regulate interstate commerce opened the door to broad federal interference with state codes in the twentieth century. In these spheres there is state authority, but it is subordinated to federal authority—a situation close to the traditional hierarchical model, not to the matrix model sometimes used for the coordinate ideal.

While the states are reserved the wider range of powers, the federal government is assigned the prime cuts among the powers. Its competences go to what are usually viewed as core areas of sovereignty—foreign relations, military, and currency—as well as to regulation of some state powers when they get too close to high politics or to interstate concerns. It already formally held most of these competences during the Confederation, but now could carry them out independently of state action. The Federalist Papers advertise this as being the main point of the Constitution: not a fearsome matter of extending the powers of the federal government into newfangled realms, but the unobjectionable matter of rendering its already agreed-upon powers effective. This effectiveness is achieved by adding the key structural characteristic of the modern sovereign state, elaborated by Hobbes in terms not dissimilar to passages in The Federalist : that of penetrating all intermediate levels and reaching down to the individual citizen to derive its authorization and, conversely, to impose its obligations.

In the early years after the Constitution, many federal powers remained dependent de facto on cooperation from the states; The Federalist ’s authors worried that the states would use this dependence to whittle away federal powers, and defended the Constitution’s provisions for federal supremacy as a protection against such whittling away. Later it was the states that became more dependent on federal cooperation. There was an undefined potential for developing the powers of the two levels of government in a cooperative or mutually dependent form; in the twentieth century, the federal government developed this into what came to be called “cooperative federalism,” wielding its superior financial resources to influence state policy in the fields of cooperation.

USE AND ABUSE OF THE FEDERALIST

The Federalist Papers have been used with increasing frequency as a guide for interpreting the Constitution. Bernard Bailyn (2003) has counted the frequency and found an almost linear progression: from occasional use by the Supreme Court in the years just after 1789 to more frequent use with every passing stage in American history. Much of this use he regards as abuse of the Papers.

The notes of Madison on the Constitutional Convention of 1787 are in principle a better source for discovering intention, but are less often used than The Federalist . They are harder to read, are harder to systematize, and have a structure of shifting counterpoint rather than consistent exposition. Moreover, they were just notes of debates where people were thinking out loud, not formal polished documents, and got off to a yawning start: they were kept secret for half a century.

The Federalist Papers , while clearer, are often subjected to questionable interpretation. Taking the Papers as gospel shorn from context, the result can be to stand the purpose of the authors on its head.

The crux of the problem is the fact that The Federalist Papers were both polemically vigorous and politically prudent. They were intended to promote ratification of a stronger central government as something that could sustain itself, sink deeper roots, and grow higher capabilities over time. In doing so, they often found it expedient to emphasize how weak the Constitution was and portray it as incapable of being stretched in the ways that opponents feared and proponents sometimes quietly wished. They cannot always be taken at face value.

To locate the original intention of the Constitution itself, the place to start would not be The Federalist Papers , but—as Madison did in The Federalist No. 40—the authorizing resolutions for the Constitutional Convention. There one finds a clear and repeated expression of purpose, namely, to create a stronger federal government, and specifically to “render the federal Constitution adequate to the exigencies of government and the preservation of the Union” (Madison 1788). Next one would have to look at the brief statement of purpose in the preamble of the Constitution. There, the lead purpose is “in Order to form a more perfect Union,” followed by a number of more specific functional purposes understood to be bound up with a more perfect union.

The intention of the wording of the Constitution would be found by looking at the Committee on Style at the Constitutional Convention, a group dominated by centralizing federalists. It took the hard substance of the constitutional plan that had been agreed upon in the months of debate, and proceeded to rewrite it in a soft cautious language, restoring important symbolic phrases of the old confederation in order to assuage the fears of the Convention’s opponents. It helped in ratification, but at the usual cost of PR: obfuscation. Theorists of nullification and secession, such as Calhoun , would later cite the confederal language as proof that each state still retained its sovereignty unchanged.

The original purpose of The Federalist Papers is the least in doubt of the entire series of documents: it was to encourage ratification and answer the critics who argued the Constitution was a blueprint for tyranny. As such, it was prone to carry further the diplomatic disguises already introduced by the Committee on Style. The authors, particularly Hamilton, argued repeatedly that, if anything, the government proposed by the Constitution would be too weak, not too strong. They said this with a purpose, not of restraining it further—as would be done by taking their descriptions of its weaknesses as indications of original intent—but of enabling its strengths to come into play and get reinforced by bonds of habit.

Hamilton in practice opposed “strict constructionism” regarding federal enumerated powers; he generally emphasized the Elastic (“necessary and proper”) Clause in the 1790's. But in The Federalist Papers , Hamilton in No. 33 justifies the Elastic and Supremacy Clauses in cautious, defensive, polemical fashion, denying any elastic intention but only the necessity of defending against what he portrays as the main danger: that of a whittling away of federal power by the states. Madison in No. 44 is slightly more expansive, arguing the necessity of recurrence in any federal constitution to “the doctrine of construction or implication” and warning against the ruinously constrictive construction that the states would end up applying to federal powers in the absence of the Elastic Clause. The logical implication was that either one side or the other—either the federal government or the states—must dominate the process of construing the extent of federal powers, and his preference in 1787–88 was for the federal government to predominate. In The Federalist , he warned against continuing dangers of interposition by the states against federal authority; at the Convention, he had advocated a congressional “negative” on state laws, that is, a federal power of interposition against state laws, as the only way of preventing individual states from flying out of the common orbit. While a legislative negative was rejected at the Convention, a judicial negative was later achieved in practice by the establishment of judicial review under a Federalist-led Supreme Court. Hamilton in The Federalist Nos. 78 and 80 provided support for judicial review, arguing—in defensive form as ever—that it was needed for preventing state encroachments from reducing the Constitution to naught.

The Elastic Clause was a residuum at the end of the Constitutional Convention flowing from the original pre-Convention resolutions. The resolutions called for powers “adequate to the exigencies of the Union”; the Convention met and enumerated the federal powers and structures that it could specifically agree on, then invested the remainder of its mandate into the Elastic and Supremacy Clauses, in which the Constitution makes itself supreme and grants its government all powers “necessary and proper” for carrying out the functions it specifies. There is a direct historical line in this, extending afterward to Hamilton’s broad construction of the Elastic Clause in the 1790's. From beginning to end, the underlying thought is dynamic, to do all that is necessary for union and government. The static, defensive exegesis of the Elastic Clause in The Federalist Papers , and in subsequent conceptions of strict construction, is implausible.

THE FEDERALIST AND THE GLOBAL SPREAD OF MODERN FEDERATION

The success of the modern federation in the United States after 1789 made it the main norm for subsequent federalism. The Federalist Papers provided the template for federation building; Hamilton was celebrated as its greatest evangelist. Switzerland reformed its confederation in 1848 and 1870 along the lines of modern federation. The new Latin American countries also often adopted federal constitutions in this period, although their implementation of federalism, like that of democracy itself, was sketchy.

After 1865, several British emigrant colonies adopted the overall model of modern federation: first the Canadian colonies (despite using the name “confederation”), then the Australian ones (using “commonwealth”), then South Africa (using “union”; there the ideological role of Hamilton and The Federalist was enormous, and the result was almost a unitary state). After 1945, several countries emerging out of the British dependent empire, such as India and Nigeria, adopted variants of modern federation. Defeated Germany and Austria also adopted federal constitutions. Later, other European and Third World countries also federalized their formerly unitary states. The process is by no means finished. Enumerating all the countries that had developed federal elements in their governance, Daniel Elazar concluded in the 1980's that a “federal revolution” was in process.

Once modern federation was known as a solution to the limitations of confederation, there has been less tolerance for the inconsistencies of confederation. Confederalism was a compromise between the extremes of separation and a unitary centralized state, splitting the difference; modern federation is more like a synthesis that upgrades both sides. What in previous millennia could be seen in confederalism as a lesser evil and a reasonable price to pay for avoiding the extremes, after 1787 came to seem like a collection of unnecessary contradictions: and if unnecessary, then also intolerable, once compared to what was available through modern federation.

The Federalist Papers have themselves been the strongest propagators of the view that confederalism is an inherently failed system. They made their case forcefully, not as scholars but as debaters for ratifying the Constitution. Their case was one-sided but had substance. They showed that confederation, even when successful, was working on an emergency basis, or else on a basis of special fortunate circumstances or external pressures. They offered in its place a structure that could work well on an ordinary systematic basis, without incessant crises or fears of collapse or dependence on special circumstances.

In recent years, it has been argued that Swiss confederalism was an impressive success, and so in a sense it was, holding together for half a millennium. Yet half a century after modern federation was invented in the United States, the Swiss found their old confederal system a failure and replaced it with one modeled along the lines of the modern federal one. The description of the old Swiss confederation as a failure became a commonplace; it entered into the realm of patriotic Swiss conviction. The judgment looks too harsh when the length of the two historical experiences are viewed side by side, yet has carried conviction in an evolutionary sense, as the cumulative outcome of historical experience. After the Constitution and The Federalist Papers , confederalism could not remain as successful in terms of longevity as it had been previously; the historical space for it shrank, while new and larger spaces opened up for modern federation. The advance of technology worked in the same direction, increasing interdependence within national territories and making localities more intertwined.

Despite the shrinkage of space for confederation within national bounds, confederation took on new force on another level. The American Union’s survival of the Civil War and consolidation afterwards gave a further impetus to discussion of modern federation, understood not only as a static technique for more sophisticated government within a given space, but also as a dynamic method of uniting people across wider spaces, in order to meet the needs of modern technological progress and the growth of interdependence. International federalist movements emerged after 1865, taking The Federalist Papers as their bible. They gained influence in the face of the world wars of the 1900's, feeding into the development of international organizations ranging from very loose and weak ones to integrative alliances and confederations such as NATO and the EU. The missionary ideology of The Federalist , used by its proponents for pummeling confederation, led on the international level to new confederations. When some (such as the League of Nations) were viewed as failures, further missionary use of The Federalist fed into the formation of still more confederations, often stronger and better conceived but confederations nonetheless, even if (as in the case of the EU) with a genetic plan of evolving into a federation. Federation seemed no less necessary but more difficult than federalist propagandists had suggested. Reflection on this situation led to an academic school of integration theory in the 1950's and 1960's, which treated functionalism and confederation as necessary historical phases in integration; in the neofunctionalist version of the theory it would lead eventually to federation, and in the version of Karl Deutsch it need not move beyond a “pluralistic security-community.” The work of Deutsch tied in with the view that confederation had been a greater success historically than was usually credited; to prove the success of the American confederation, Deutsch and his colleagues cited Merrill Jensen, an historian highly critical of The Federalist and friendly to the Anti-Federalists or Confederalists. Jensen argued that the Articles of Confederation had been a success, contrary to the American patriotic story that paralleled the Swiss one in condemning the confederalist experience. The relevance of The Federalist Papers was seen in this new literature as minimal, except at the final stages of a process that was only beginning and that the Papers themselves mystified as a matter of tactical necessity for getting a difficult decision made. Their exaggerations of the defects of confederalism were highlighted; their argument that only federation would “work” was seen as both a mistake and a diversion from the direction that progress would actually need to take in this era. It was only their normative orientation that was seen as helpful. The very success of The Federalist Papers had led to their partial eclipse. Nevertheless, their eclipse on the supranational level may not be permanent, and their influence on the level of national constitutionalism has remained enormous throughout.

Last updated: 2006

SEE ALSO: Anti-Federalists ; Federalists ; Hamilton, Alexander ; Madison, James

- Historical Events

- This page was last edited on 4 July 2018, at 21:08.

- Content is available under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike unless otherwise noted.

- Privacy policy

- Federalism in America

- Disclaimers

The American Founding

Introduction to the Federalist Papers

Origin of the Federalist

The 85 essays appeared in one or more of the following four New York newspapers: 1) The New York Journal , edited by Thomas Greenleaf, 2) Independent Journal , edited by John McLean, 3) New York Advertiser , edited by Samuel and John Loudon, and 4) Daily Advertiser , edited by Francis Childs. This site uses the 1818 Gideon edition. Initially, they were intended to be a 20-essay response to the Antifederalist attacks on the Constitution that were flooding the New York newspapers right after the Constitution had been signed in Philadelphia on September 17, 1787. The Cato letters started to appear on September 27, George Mason ‘s objections were in circulation and the Brutus Essays were launched on October 18. The number of essays in The Federalist was extended in response to the relentless, and effective, Antifederalist criticism of the proposed Constitution .

McLean bundled the first 36 essays together—they appeared in the newspapers between October 27, 1787 and January 8, 1788—and published them as Volume 1 on March 22, 1788. Essays 37 through 77 of The Federalist appeared between January 11 and April 2, 1788. On May 28, McLean took Federalist 37-77 as well as the yet to be published Federalist 78-85 and issued them all as Volume 2 of The Federalist . Between June 14 and August 16, these eight remaining essays— Federalist 78-85—appeared in the Independent Journal and New York Packet .

THE STATUS OF THE FEDERALIST

One of the persistent questions concerning the status of The Federalist is this: is it a propaganda tract written to secure ratification of the Constitution and thus of no enduring relevance or is it the authoritative expositor of the meaning of the Constitution having a privileged position in constitutional interpretation? It is tempting to adopt the former position because 1) the essays originated in the rough and tumble of the ratification struggle. It is also tempting to 2) see The Federalist as incoherent; didn’t Hamilton and Madison disagree with each other within five years of co-authoring the essays? Surely the seeds of their disagreement are sown in the very essays! 3) The essays sometimes appeared at a rate of about three per week and, according to Madison , there were occasions when the last part of an essay was being written as the first part was being typed.

- One should not confuse self-serving propaganda with advocating a political position in a persuasive manner. After all, rhetorical skills are a vital part of the democratic electoral process and something a free people have to handle. These are op-ed pieces of the highest quality addressing the most pressing issues of the day.

- Moreover, because Hamilton and Madison parted ways doesn’t mean that they weren’t in fundamental agreement in 1787-1788 about the need for a more energetic form of government. And just because they were written with a certain haste, doesn’t mean that they were unreflective and not well written. Federalist 10 , the most famous of all the essays, is actually the final draft of an essay that originated in Madison ‘s Vices in 1787, matured at the Constitutional Convention in June 1787, and was refined in a letter to Jefferson in October 1787. All of Jay ‘s essays focus on foreign policy, the heart of the Madisonian essays are Federalist 37-51 on the great difficulty of founding, and Hamilton tends to focus on the institutional features of federalism and the separation of powers.

I suggest, furthermore, that the moment these essays were available in book form, they acquired a status that went beyond the more narrowly conceived objective of trying to influence the ratification of the Constitution . The Federalist now acquired a “timeless” and higher purpose, a sort of icon status equal to the very Constitution that it was defending and interpreting. And we can see this switch in tone in Federalist 37 when Madison invites his readers to contemplate the great difficulty of founding. Federalist 38 , echoing Federalist 1 , points to the uniqueness of the America Founding: never before had a nation been founded by the reflection and choice of multiple founders who sat down and deliberated over creating the best form of government consistent with the genius of the American people. Thomas Jefferson referred to the Constitution as the work of “demigods,” and The Federalist “the best commentary on the principles of government, which ever was written.” There is a coherent teaching on the constitutional aspects of a new republicanism and a new federalism in The Federalist that makes the essays attractive to readers of every generation.

AUTHORSHIP OF THE FEDERALIST

A second question about The Federalist is how many essays did each person write? James Madison —at the time a resident of New York since he was a Virginia delegate to the Confederation Congress that met in New York— John Jay , and Alexander Hamilton —both of New York wrote these essays under the pseudonym, “Publius.” So one answer to the question is that it doesn’t matter since everyone signed off under the same pseudonym, “Publius.” But given the icon status of The Federalist , there has been an enduring curiosity about the authorship of the essays. Although it is virtually agreed that Jay wrote only five essays, there have been several disputes over the decades concerning the distribution of the essays between Hamilton and Madison . Suffice it to note, that Madison ‘s last contribution was Federalist 63 , leaving Hamilton as the exclusive author of the nineteen Executive and Judiciary essays. Madison left New York in order to comply with the residence law in Virginia concerning eligibility for the Virginia ratifying convention . There is also widespread agreement that Madison wrote the first 13 essays on the great difficulty of founding. There is still dispute over the authorship of Federalist 50-58, but these have persuasively been resolved in favor of Madison .

OUTLINE OF THE FEDERALIST

A third question concerns how to “outline” the essays into its component parts. We get some natural help from the authors themselves. Federalist 1 outlines the six topics to be discussed in the essays without providing an exact table of contents. The authors didn’t know in October 1787 how many essays would be devoted to each topic. Nevertheless, if one sticks with the “formal division of the subject” outlined in the first essay, it is possible to work out the actual division of essays into the six topic areas or “points” after the fact so to speak.

Martin Diamond was one of the earliest scholars to break The Federalist into its component parts. He identified Union as the subject matter of the first 36 Federalist essays and Republicanism as the subject matter of the last 49 essays. There is certain neatness to this breakdown, and accuracy to the Union essays. The fist three topics outlined in Federalist 1 are:

- The utility of the union

- The insufficiency of the present confederation under the Articles of Confederation

- The need for a government at least as energetic as the one proposed.

The opening paragraph of Federalist 15 summarizes the previous 14 essays and says: “in pursuance of the plan which I have laid down for the pursuance of the subject, the point next in order to be examined is the ‘insufficiency of the present confederation.’” So we can say with confidence that Federalist 1-14 is devoted to the utility of the union. Similarly, Federalist 23 opens with the following observation: “the necessity of a Constitution, at least equally energetic as the one proposed…is the point at the examination of the examination at which we are arrived.” Thus Federalist 15-22 covered the second point dealing with union or federalism. Finally, Federalist 37 makes it clear that coverage of the third point has come to an end and new beginning has arrived. And since McLean bundled the first 36 essays into Volume 1, we have confidence in declaring a conclusion to the coverage of the first three points all having to do with union and federalism.

The difficulty with the Diamond project is that it becomes messy with respect to topics 4, 5, and 6 listed in Federalist 1 : 4) the Constitution conforms to the true principles of republicanism , 5) the analogy of the Constitution to state governments, and 6) the added benefits from adopting the Constitution . Let’s work our way backward. In Federalist 85 , we learn that “according to the formal division of the subject of these papers announced in my first number, there would appear still to remain for discussion two points,” namely, the fifth and sixth points. That leaves, “republicanism,” the fourth point, as the topic for Federalist 37-84, or virtually the entire Part II of The Federalist .

I propose that we substitute the word Constitutionalism for Republicanism as the subject matter for essays 37-51, reserving the appellation Republicanism for essays 52-84. This substitution is similar to the “Merits of the Constitution ” designation offered by Charles Kesler in his new introduction to the Rossiter edition; the advantage of this Constitutional approach is that it helps explain why issues other than Republicanism strictly speaking are covered in Federalist 37-46. Kesler carries the Constitutional designation through to the end; I suggest we return to Republicanism with Federalist 52 .

Finally, to assist the reader in following the argument of The Federalist , I have broken the argument down into seven major parts. This breakdown follows the open ended one provided in Federalist 1 . This can be used in conjunction with the Essay-by-Essay Summary and the actual text of The Federalist .

Note: The text of The Federalist used on this site is from the edition reviewed by James Madison and published by Jacob Gideon in 1818. There may be slight variations in language from the essays as originally published.

State: Virginia

Age at Convention: 36

Date of Birth: March 16, 1751

Date of Death: June 28, 1836

Schooling: College of New Jersey (Princeton) 1771

Occupation: Politician

Prior Political Experience: Lower House of Virginia 1776, 1783-1786, Upper House of Virginia 1778, Virginia State Constitutional Convention 1776, Confederation Congress 1781- 1783, 1786-1788, Virginia House of Delegates 1784-1786, Annapolis Convention Signer 1786

Committee Assignments: Third Committee of Representation, Committee of Slave Trade, Committee of Leftovers, Committee of Style

Convention Contributions: Arrived May 25 and was present through the signing of the Constitution. He is best known for writing the Virginia Plan and defending the attempt to build a stronger central government. He kept copious notes of the proceedings of the Convention which were made available to the general public upon his death in 1836. William Pierce stated that “Mr. Madison is a character who has long been in public life; and what is very remarkable every Person seems to acknowledge his greatness. He blends together the profound politician, with the Scholar. … The affairs of the United States, he perhaps, has the most correct knowledge of, of any Man in the Union.”

New Government Participation: Attended the ratification convention of Virginia and supported the ratification of the Constitution. He also coauthored the Federalist Papers. Served as Virginia’s U.S. Representative (1789-1797) where he drafted and debated the First Twelve Amendments to the Constitution; ten of which became the Bill of Rights; author of the Virginia Resolutions which argued that the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 were unconstitutional. Served as Secretary of State (1801-1809) Elected President of the United States of America (1809-1817).

Biography from the National Archives: The oldest of 10 children and a scion of the planter aristocracy, Madison was born in 1751 at Port Conway, King George County, VA, while his mother was visiting her parents. In a few weeks she journeyed back with her newborn son to Montpelier estate, in Orange County, which became his lifelong home. He received his early education from his mother, from tutors, and at a private school. An excellent scholar though frail and sickly in his youth, in 1771 he graduated from the College of New Jersey (later Princeton), where he demonstrated special interest in government and the law. But, considering the ministry for a career, he stayed on for a year of postgraduate study in theology.

Back at Montpelier, still undecided on a profession, Madison soon embraced the patriot cause, and state and local politics absorbed much of his time. In 1775 he served on the Orange County committee of safety; the next year at the Virginia convention, which, besides advocating various Revolutionary steps, framed the Virginia constitution; in 1776-77 in the House of Delegates; and in 1778-80 in the Council of State. His ill health precluded any military service.

In 1780 Madison was chosen to represent Virginia in the Continental Congress (1780-83 and 1786-88). Although originally the youngest delegate, he played a major role in the deliberations of that body. Meantime, in the years 1784-86, he had again sat in the Virginia House of Delegates. He was a guiding force behind the Mount Vernon Conference (1785), attended the Annapolis Convention (1786), and was otherwise highly instrumental in the convening of the Constitutional Convention in 1787. He had also written extensively about deficiencies in the Articles of Confederation.

Madison was clearly the preeminent figure at the convention. Some of the delegates favored an authoritarian central government; others, retention of state sovereignty; and most occupied positions in the middle of the two extremes. Madison, who was rarely absent and whose Virginia Plan was in large part the basis of the Constitution, tirelessly advocated a strong government, though many of his proposals were rejected. Despite his poor speaking capabilities, he took the floor more than 150 times, third only after Gouverneur Morris and James Wilson. Madison was also a member of numerous committees, the most important of which were those on postponed matters and style. His journal of the convention is the best single record of the event. He also played a key part in guiding the Constitution through the Continental Congress.

Playing a lead in the ratification process in Virginia, too, Madison defended the document against such powerful opponents as Patrick Henry, George Mason, and Richard Henry Lee. In New York, where Madison was serving in the Continental Congress, he collaborated with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay in a series of essays that in 1787-88 appeared in the newspapers and were soon published in book form as The Federalist (1788). This set of essays is a classic of political theory and a lucid exposition of the republican principles that dominated the framing of the Constitution.

In the U.S. House of Representatives (1789-97), Madison helped frame and ensure passage of the Bill of Rights. He also assisted in organizing the executive department and creating a system of federal taxation. As leaders of the opposition to Hamilton’s policies, he and Jefferson founded the Democratic-Republican Party.

In 1794 Madison married a vivacious widow who was 16 years his junior, Dolley Payne Todd, who had a son; they were to raise no children of their own. Madison spent the period 1797-1801 in semiretirement, but in 1798 he wrote the Virginia Resolutions, which attacked the Alien and Sedition Acts. While he served as Secretary of State (1801-9), his wife often served as President Jefferson’s hostess.

In 1809 Madison succeeded Jefferson. Like the first three Presidents, Madison was enmeshed in the ramifications of European wars. Diplomacy had failed to prevent the seizure of U.S. ships, goods, and men on the high seas, and a depression wracked the country. Madison continued to apply diplomatic techniques and economic sanctions, eventually effective to some degree against France. But continued British interference with shipping, as well as other grievances, led to the War of 1812.

The war, for which the young nation was ill prepared, ended in stalemate in December 1814 when the inconclusive Treaty of Ghent which nearly restored prewar conditions, was signed. But, thanks mainly to Andrew Jackson’s spectacular victory at the Battle of New Orleans (Chalmette) in January 1815, most Americans believed they had won. Twice tested, independence had survived, and an ebullient nationalism marked Madison’s last years in office, during which period the Democratic-Republicans held virtually uncontested sway.

In retirement after his second term, Madison managed Montpelier but continued to be active in public affairs. He devoted long hours to editing his journal of the Constitutional Convention, which the government was to publish 4 years after his death. He served as co-chairman of the Virginia constitutional convention of 1829-30 and as rector of the University of Virginia during the period 1826-36. Writing newspaper articles defending the administration of Monroe, he also acted as his foreign policy adviser.

Madison spoke out, too, against the emerging sectional controversy that threatened the existence of the Union. Although a slaveholder all his life, he was active during his later years in the American Colonization Society, whose mission was the resettlement of slaves in Africa.

Madison died at the age of 85 in 1836, survived by his wife and stepson.

Age at Convention: 62

Date of Birth: December 11,1725

Date of Death: October 7, 1792

Schooling: Personal tutors

Occupation: Planter and Slave Holder, Lending and Investments, Real Estate Land Speculation, Public Security Investments, Land owner

Prior Political Experience: Author of Virginia Bill of Rights, State Lower House of Virginia 1776-1780, 1786-1787, Virginia State Constitutional Convention 1776

Committee Assignments: First Committee of Representation, Committee of Assumption of State Debts, Committee of Trade, Chairman Committee of Economy, Frugality, and Manufactures

Convention Contributions: Arrived May 25 and was present through the signing of the Constitution, however he did not sign the Constitution. Initially Mason advocated a stronger central government but withdrew his support toward the end of the deliberations. He argued that the Constitution inadequately represented the interests of the people and the States and that the new government will “produce a monarchy, or a corrupt, tyrannical aristocracy.” William Pierce stated that “he is able and convincing in debate, steady and firm in his principles, and undoubtedly one of the best politicians in America.” He kept notes of the debates at the Convention.

New Government Participation: He attended the ratification convention of Virginia where he opposed the ratification of the Constitution. Did not serve in the new Federal Government.

Biography from the National Archives: In 1725 George Mason was born to George and Ann Thomson Mason. When the boy was 10 years old his father died, and young George’s upbringing was left in the care of his uncle, John Mercer. The future jurist’s education was profoundly shaped by the contents of his uncle’s 1500-volume library, one-third of which concerned the law.

Mason established himself as an important figure in his community. As owner of Gunston Hall he was one of the richest planters in Virginia. In 1750 he married Anne Eilbeck, and in 23 years of marriage they had five sons and four daughters. In 1752 he acquired an interest in the Ohio Company, an organization that speculated in western lands. When the crown revoked the company’s rights in 1773, Mason, the company’s treasurer, wrote his first major state paper, Extracts from the Virginia Charters, with Some Remarks upon Them.