- Current Issue

- All Articles

- Best Sellers

- New Releases

- Print and Book Bundles

- Coming Soon

- Limited Editions

- Portfolios and Sets

- Back Issues

- Aperture PhotoBook Club

- Aperture Conversations

- Member Events

- Online Resources

- Internships

- Professional Development

- Educational Publications

- Portfolio Prize

- PhotoBook Awards

- Creator Labs Photo Fund

- Connect Council

- Patron Circle

- Annual Fund

- Capital Campaign

- Corporate Opportunities

- Planned Giving

- Vision & Justice Book Series

A New Digital Platform Asks What Truth Means in Photography

With issues of truth more pressing than ever, alan govenar started an online space for critical discussion about the role of images in contemporary life. here, he speaks about projects from istanbul to the bronx..

Sabiha Çimen, Quran School students having fun with a pink smoke bomb at a picnic event, Istanbul, Turkey, 2017 © Sabiha Çimen/Magnum Photos

Chris Boot: Earlier this year, you started a website for photography debates and as a meeting place for ideas, Truth in Photography , which has just launched its second edition. Can you start by telling me why the focus on truth?

Alan Govenar: Issues of truth are more pressing than ever. We’re all looking for truth, particularly as it relates to current events, news, photography. The possibilities for manipulation of the truth have never been greater, given the technological advances over the last decades. Truth in photography is a question, not an answer. Truth in photography is a perception. It’s a feeling. In many ways, it’s intangible.

Boot: It’s clear from the second edition that the arguments and issues are evolving. It ranges from Nigel Poor’s work within the prison system, The San Quentin Project , that began as a feature in the “ Prison Nation ” issue of Aperture magazine and is now a book, published by Aperture.

There’s a piece about the Bronx Documentary Center, another about the girls of Quran schools by the Magnum photographer Sabiha Ҫimen.

Govenar: She is one of the most fascinating new contributors. What’s particularly interesting is that she is a young photographer, and this work related to the Quran schools is her most personal. She told me that in these photographs, she sees herself. She attended Quran schools. Her sisters attended Quran schools. And what she has been striving to depict in her photographs is a sense of what the girls are experiencing, how they manifest their inner lives. Growing up, she was told by her mother that the headscarf was liberating, that if she wore a headscarf, then she could mix in the world. But her mother was also committed to her getting a secular education. So, for her to go into the Quran schools—not only is she in some sense realizing a truth about herself, but she’s also looking at how these girls dress essentially the same, how they engage in group activities, what their fantasies are.

Boot: Her text is incredibly powerful. It’s probably relevant to mention that she’s Turkish and grew up in Istanbul, so she’s right at that crossroads of the secular West and the Muslim East. What she has to say about her adoption of the scarf and how that changed her and made different kinds of photographs possible is a moving piece of writing in addition to the photographs.

Her work, in a way, is both core to a kind of changing set of values in photography, which, judging by the content of Truth in Photography, you’re thinking about and monitoring. And clearly, the Me Too and Black Lives Matter movements have had an enormous impact on the field. Do you see a new ethics for photography emerging, and if so, how would you describe the contours of that?

Govenar: I think the awareness, the consciousness, of ethics in photography have become more apparent, more visible. Photographers are having to discuss ethics, perhaps in a way that they have not before. But historically, for me, the ethics of photography are never neutral. Photographers and photography take a position, a point of view that’s inherent to the framing in which the images are made. This has always been an issue. Issues of truth are time-honored and time-debated, maybe time-disregarded. But we now face this floodgate of images daily. We have to somehow try to make sense of them.

Boot: It does feel like the words “cultural revolution,” as they apply to what’s happened in the last few years and particularly last year, have real meaning here. Would you agree with that?

Govenar: I would. But I think in a larger sense, it’s not only those issues. It’s the systemic issues, because so much of the production of photography, particularly as it relates to photojournalism, is driven by magazine editors, newspaper editors, online news editors.

And then the other spectrum is fine art photography—or what we like to think of as fine art photography, when in fact, for me, it’s a kind of artificial hierarchy that emerges in photography beginning with Stieglitz. While photography is perhaps, intrinsically, the most democratic of all art forms—anyone can make a photograph if you have a camera, and it’s become easier—but photographs are not considered equal. The technical and aesthetic criteria by which we judge them is also part of the issue: How do we see the image? How do we feel the image?

Those are the issues that are not often discussed. But then how are the subjects that photographers focus on prioritized? One of the areas in the spring edition that we introduced is this idea of the struggle for gun control. I was very surprised to find, in searching the Magnum photo archive, that there were no photographs ever made of gun buybacks, which have been happening for decades in the United States and in other places around the world. We’re featuring a portfolio of work by Alessandra Sanguinetti of the March for Our Lives protests. She photographed one of these demonstrations. They were held all over the country.

Boot: You’re identifying a gap in the perspective. I mean, it does seem like Magnum, and not Magnum alone, but a generation of photographers who perhaps have taken advantage of, let’s call it photographer’s privilege—they could go anywhere and had the privilege of viewing others the way that they were not viewed. That was, in a sense, the essence of photography for many years. These quixotic individuals who could adapt and fit in and record without necessarily having a responsibility to their subjects—although I do very vividly recall a conversation with Philip Jones Griffiths several years ago, where he discounted any photographs that were made without the implicit consent of the subjects, i.e. that his idea of photography was rooted in the sense of serving the subject rather than just catching the subject.

But that generation of photographers is deeply challenged by this new environment. Magazines and the media generally have to think differently about who they commission and what viewpoints they adopt, with much more attention paid to the subjects, paid to whom the subjects would wish to be recorded by, obviously with a drive towards more inclusivity and balance in their commissioning practices. Is that something you encounter in your work, this sense of the older generation being profoundly challenged by new thinking?

Govenar: Consent and context are critical in the making of photography, in the publishing of photography, in the exhibition of photography and its presentation in various media. It’s always been a concern of mine. I founded Documentary Arts in 1985 to have a holistic approach, a way of seeing the still photograph as important, but also to focus on not only, how an individual image can become iconic, but on issues of context and the ways we can contextualize the image in different media. To really understand what is happening around us or what we are experiencing, we need to also listen to audio, or see film, or video. If there is truth in photography, it’s in the multitude of perspectives. And that isn’t limited to the factual media. Sometimes it’s in the interpretation. Sometimes there’s more truth in fiction, than in what appears to be factual. Ultimately, truth in photography is intangible, it’s about what we sense, what we identify with, or perhaps know through the realm of experience.

Boot: One of the things that occurs to me about the future of photography is, well, take New York City, for example. You’re out and about with your camera in New York. Subjects are not passive. There are rules of respect and consent that go with the territory of a highly empowered society, let’s call it that. Whereas the history of photography is marked by colonialism and photography served colonial purposes., While much of that has changed, there has been a different attitude to subjects and consent from photographers working in places where people don’t have a voice in the same way.

It occurs to me now that you have to treat every subject the way you would your mother, your brother, another New Yorker. You just can’t have a hierarchy depending on where you are photographing.

Govenar: Part of what we’re trying to do is present the work of professional photographers side by side with the work of community-based photographers and vernacular photography. In the 1980s, I started writing about this concept of community photography. Until that point, discussions of community photography were largely focused on content, what was in the picture. What I was interested in was the process through which these photographs were made. I had received a commission from the Dallas Museum of Art to create a project called Living Texas Blues , and, and at that time, there was a two-volume history of Texas photography being published by Texas Monthly Press. And there was not a single African American photographer represented. When I talked to the curators who were both at major institutions in the state, they said, “Well, we only had time to work with existing collections, and we couldn’t identify any known African American photographers in an existing collection.”

That was in 1985. And that’s when I founded Documentary Arts. Our first major project was focused on African American photography. It’s when I went to New York to meet with Cornell Capa to discuss some of these issues with him. He introduced me to Deborah Willis , who’s been a colleague for decades and who’s been very enthusiastic about the work of Documentary Arts.

In 1995, my wife Kaleta Doolin and I founded the Texas African American Photography Archive. In the first edition of Truth in Photography, we featured a selection from the sixty thousand images that we collected and form the core corpus of this archive. But the bigger point here is that we have worked to present community photographers, who were actively involved in their communities. On the Truth in Photography website, you can hear the voices of the photographers and watch video of people in their communities talking about their work. So, in a sense, what’s being advocated today, which is consent, context, and transparency about the nature of the interaction between the photographer and his or her subjects, the collaborative portrait—all very important ideas—this is the way community photographers have historically worked.

I organized and curated an exhibition on Alonzo Jordan for the International Center of Photography that opened in 2011. He was a barber in the town of Jasper, Texas. His barber shop, when he wasn’t cutting hair, was his studio. His living room was his studio. And he worked in a seventy-mile radius around Jasper in little towns, making photographs. The photograph had greater significance than just what was in it, what the subject was. It was the way in which the subject was depicted and portrayed.

Boot: And the way that image played a role in family lives, individual lives, community lives.

Govenar: And the self-esteem of the subjects. So, when we’re talking today about a new ethics that needs to address these same issues, I think what we’re also talking about is the need to broaden our knowledge of the history of photography.

When the book on Alonzo Jordan was published by Steidl in 2011, it inserted someone who was a total no-name in the history of photography into the canon of photography When we talk about the new ethics, we have to include a reassessment of history going back even into the nineteenth century.

Photobooks have become so important in our world today as a mechanism for transmitting and communicating the work of exciting new photographers but also reassessing historical images. Aperture magazine has also gone in that direction. What we’re doing on the Truth in Photography platform, is, in part, reprinting older articles. For example, in the spring edition, in citizen journalism, we’re reprinting an Aperture magazine article on polling places, for which people were asked to photograph the places where they vote. It’s a wonderful article. And it’s a way to take photographs that were made in the past and present them in the new context. Because we see them differently today. Context defines our perception.

![truth in photography essay Volunteers who sang and delivered Xmas packages to SHU [Secure Housing Units], December 25, 1975](https://aperturewp.wpenginepowered.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/NP_016_Mapping-HR-1024x666.jpg)

Boot: It’s very interesting you should talk about community photography. As it happens, my first job in photography was in London in the 1980s within a community arts and photography movement that was all about empowerment, empowering the subject, empowering people to tell their own stories and photographs as an alternative to the objectification of a professional media. Have you looked at the community photography movement in Britain in the 1980s?

Govenar: Very much so. When I started writing about community photography, one of the photographers whose work I admired was Val Wilmer, whom I’m sure you knew.

Govenar: Val introduced me to exactly what you were talking about. She was immediately interested in what I was starting to write and think about. And one of the first publications—and probably the first outside the United States—of one of these images that I was working with was in that magazine Ten.8 , which was such an important photographic journal. Through Val, I was introduced to the Photographers’ Gallery. I didn’t know that much about it, but I was definitely in tune with that. Going to London in the 1980s—you and I didn’t know each other, but we were focused on some of the same issues. It was also around the same time that I met Simon Njami, who was publishing his journal Revue Noire and publishing little photobooks about then-unknown African photographers who were essentially community photographers in different parts of Africa.

There were other parallels. Certainly, the work that was being done by African American community photographers paralleled work that was being done in Latino and Jewish communities. In a sense, by understanding community photography, we had a lens to better understand, for example, the work of Roman Vishniac and others.

Part of it is that we’re searching for the factual in photography because the way photography has evolved is that we’ve tended to attribute higher value to images that aren’t factual, not only as commodities in the art world and artworks. So, the image that is the faux reality may be worth more from a monetary standpoint than the image of something that is factual and accurate.

But it’s interesting to see how things are turning now. In my interview with Clément Chéroux, he talked about how the need for us to know what is factual and accurate is increasingly more important to us, because there’s so much that is false. Sadly, some photographs of fictional realities have created the groundwork for what we now call misinformation. Ten years ago, it was called art. Maybe it’s still called art, and maybe, it should be called something else.

Boot: Alan, I congratulate you on the work you’ve done over your lifetime of expanding the understanding of photography and what you’re doing today with Documentary Arts and with Truth in Photography. Thank you for sharing your thoughts with Aperture.

You May Also Like

The Musicians Who Energized a Revolution in Nepal

Close Encounters with Miranda July

Mariko Mori’s Anime-Inspired Critique of Gender in Japan

The World Is Martin Parr’s Runway

What Christopher Gregory-Rivera Discovered in Puerto Rico’s State Secrets

Annie Ernaux Inspires an Exhibition about Fleeting Encounters

Naomieh Jovin’s Photo Collages of Haitian American Life

How One Photographer Documented Ghana’s Transformations

In Public Spaces, Tender Photographs about Love and Friendship

How Kishin Shinoyama Found Fame and Controversy

Truth in photography: Perception, myth and reality in the postmodern world

Photography uses the archetype of beauty as a connection to truth., leslie mullen.

Photography was originally considered a way to objectively represent reality, completely untouched by the photographer’s perspective. However, photographers manipulate their pictures in various ways, from choosing what to shoot to altering the resulting image through computer digitalization. The manipulation inherent to photography brings to light questions about the nature of truth. All art forms manipulate reality in order to reveal truths not apparent to the uncritical eye.

Scientific, news, artistic and documentary photography all use the archetype of beauty as a connection to truth. Beauty, however, is based on the beliefs of a culture and does not necessarily define truth. Understanding of photographic truth, like all other truths, depends on an understanding of culture, belief, history, and the universal aspects of human nature.

[This is an abstract of the original thesis presented to the graduate school of the University of Florida in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of master of arts in mass communication, University of Florida 1998]

Many people see the phrase “Truth in Journalism” as an oxymoron these days. From such incidents as an NBC news crew blowing up a car to illustrate the dangers of a particular brand of automobile, to a reporter for the Boston Globe who admitted that she created sources in order to better tell a story, the public is left wondering what in journalism is really true and what is fabricated. This mistrust extends to the photographs used in news stories. With digital manipulation, for instance, photographs can be seamlessly altered to reflect whatever the photographers or editors wish to show. When the O.J. Simpson murder case was the biggest news story of the day, the picture of Simpson on Time’s cover had noticeably darker skin than the same mug shot picture featured on Newsweek or another prominent news magazines. When the public became aware of the altered photograph, Time justified the manipulation by calling the picture “cover art,” and therefore not subject to the same standards as straight news photographs. Adam Clayton Powell III wrote, “The editors argued that it was not unethical, because Time covers are art, not news, a possible surprise to unsuspecting readers who thought they were looking at photographic reality.” A news photograph is often not just an interesting picture used to highlight a story; sometimes, it is a mode of storytelling that incorporates ideas of truth, reality, cultural value systems, and perception.

A History of Manipulation When photography was first introduced 150 years ago, it was seen as the perfect documentary medium because the mechanical nature of the medium ensured unadulterated, exact replicas of the subject matter. The technological advances of cameras and the subsequent development of photojournalism led to clearer, more realistic photos. Although many news photographers claim their photographs represent the undistorted truth, in actuality a great deal of manipulation goes into the production and publication of a photograph. The photographer chooses what aspect of reality he wishes to represent both when he takes the picture, and when he readies it for publication. Even when a photographer tries to capture the scene precisely, he may miss representing the essence of the scene before him.

Digital Imaging Computer technology has been applied to photography, creating digital imaging and a new realm of ethical qualms. Because digital images can be seamlessly altered, there has been a great deal of hand wringing about the “evils” of practicing this type of photography. The advent of digital imaging causes us to question and redefine the nature of the photographic visual medium, just as the invention of photography caused artists to re-evaluate the nature of painting.

Digital imaging actually differs from photography as much as photography differs from painting. Photographs are analogous, or continuous, representations of space with infinite spatial or tonal variations. Digital images, on the other hand, are composed of discrete pixels. The images are encoded by dividing the picture into a Cartesian grid of cells. In digital imaging, as in standard photography, writing, or conversation, we must depend on the integrity of the communicator while still maintaining a healthy dose of skepticism, so as not to be erroneously persuaded. Digital imaging is not “an evil,” as described by some in the industry, but merely another tool at the photographer’s disposal.

Photography and Perception Biologically everyone perceives images the same way. Visual sensory perception is based on the functions of the eye – light enters the eye, hits the cells of the retina, and the brain interprets the impulses of those optical cells into coherent, understandable forms. Differences in the perception of images arise from the cognitive aspect of perception – the interpretation of what those images mean. Signs are not inherently understood, but learned through living in a particular culture. Photographs are referred to as iconic signs – those signs that closely resemble the thing they represent. We read photographs as we read the world around us, a world that is full of uses, values and meanings.

Reality, Perception and Truth If reality is historically and culturally based there cannot be a “ultimate reality” but instead highly variable and subjective realities. A shift of one’s frame of reference can alter reality, and such shifts often occur, either gradually, such as in the natural development of a culture over time, or instantly, as with the discovery of a new scientific theory. If our notion of reality depends on this world that we “made up,” through our measurements, culture and history, it would follow that our notion of truth is also a product of such factors. By this view, truth is just another contextual measurement by which we judge reality. From this standpoint, how “true” or “false” something is, depends on our perceptions. If we view reality through our frames of reference, and frames of reference shift over time, it would naturally follow that our ideas of truth will change over time as well.

Sign up now

Payment failed.

Modern Philosophy and Truth The relativistic philosophy explained above, that truth is a product of culture, which alters over time, is a central conviction of postmodernism. According to the postmodern viewpoint, culture is constructed, and because our ideas of reality are entirely dependent on culture, reality is also constructed. According to postmodernists, we cannot separate our human perspective from reality, therefore we can never really know what reality is. This is why many believed photography could be the perfect postmodern art form: photography was originally seen as a purely mechanical, objective means of communication, solving the postmodern dilemma of human perceptual interference.

A quality of the photographic negative is that it allows for multiple, identical reproductions of an image. With digital photography, perfect reproductions became possible, without the degradation to which negatives were susceptible. This mechanical reproduction negates the individualism of a work of art. Some would argue that the very nature of photography created the postmodernist viewpoint. In postmodernism, there is no such state as individualism because we are all products of our culture; we are all stamped-out products of the machine age. This denial of the individual denies personal emotion and unique viewpoints. Postmodernism did not just grow out of photography, however; it also stemmed from Marxism, semiotics, poststructuralism, feminism, and psychoanalysis. Modernism has a belief in originality, progress and the power of the individual. Modernism uses the symbolic language of images, and it has a much more optimistic outlook than does postmodernism. According to modernism, we are not imprisoned by our culture, rather, by living in culture we become tutored in a rich symbolic language. The modernist theory that images contain signs which must be decoded in order to be understood comes from Structuralism. The modernist concern for the “essence and purity” of art is a concern with the representation of truth, and the modernist “belief in universality” is a belief in absolute truths. Postmodernism instead supports the relativistic position explained earlier in this paper. In the postmodern world there is no such thing as absolute truth. The postmodernist believes that truth is socially constructed. An acceptance of postmodernism does not necessarily discount modernism, even though the two often are in direct opposition. Because there does not appear to be a consensus about the definition of “truth,” it is still debated, and philosophy often plays out this debate in the art world. According to the scholar Lawrence Beyer, the whole purpose of art is to uncover hidden truths, thus making it the ideal platform from which to conduct the debate.

The Function of Art Artists aspire to achieve the same type of understanding about truth as do other schools of knowledge. The word “fact” is derived from the Latin factum: a thing done or made. Works of art, or artifacts, are made or created with skill, hence a close relationship between the words “art” and “fact.” Not only can art simplify in order to show what matters, but it can also often show us things previously unseen; art shows us more.

By taking such liberties with reality, by uncovering and revealing underlying meanings, by showing us “what matters,” the artist can help us make sense of the world. This is one reason art has always been with us. Humans have always had a need to understand who we are and why we are here. These are the fundamental questions that science and philosophy grapples with and, more often than not, fails to answer.

At times, artists have been mere tools, used by those in power to convince the masses of a particular ideology.

Art as Persuasion The ability of art to persuade the masses goes back to the beginning of written history. At times, artists have been mere tools, used by those in power to convince the masses of a particular ideology.

According to John Merryman and Albert Elsen, the concept of the artist as a political and cultural rebel is a modern idea. When artists began working independently, fulfilling their own agendas and espousing their own beliefs, they often acted in opposition to the ruling government or dominant religion. Thus, art has often been used as a form of political or social persuasion, either as a tool of the ruling class or church, or as a mode of argument against government and the values of the majority. More recently, especially with the growth of advertising, art has come to be used as a form of consumer and cultural persuasion. For instance, professional artists today practice a form of consumer persuasion when they try to attract purchasers and get them to invest in their products. Art today is more often viewed as a commodity to be bought and sold rather than as a significant political statement.

Persuasive Art: Documentary Photography One reason art is practiced is due to the human need for understanding. Another function of art is to satisfy the need to keep a record of events that are deemed significant. Before photography, events were chronicled through written accounts or through various forms of pictorial representation. Photography enabled people to document significant events with more visual accuracy than any other medium. Documentarists always knew that some manipulation was necessary in order to make a point, however much they denied it. Most documentarists never admitted to manipulation until after the documentary movement of the thirties and forties was over. But they all understood that documentary truth has to be created, that literal representation in photography can fail to signify the fact or issue at hand. Documentarists need to convey stories with meaning, and their methods in doing so can often bring documentary photography out of the world of straight news photography and closer to the realm of art.

Documentarists often try to achieve a level of drama and sensitivity in their photographs on par with art, to combine straight news photographs with artistic methods to tell a compelling, emotional story. This dramatization of truth allows photographers “to capture particular truths while simultaneously transcending them to reach a level of universal truth,” a function of art as discussed above.

Documentaries need to speak in a language the audience can understand, so documentarists often employ certain structural techniques used in fiction, “both to give coherence to the story they are telling and to ensure that audiences are able to relate to the events being played out before them.” Documentarists achieve this both in the manner of how the photographic subject is represented, in the captions that typically accompany documentary photographs, or in the story that the photographs highlight. The balance between structural and narrative ploys needed to increase interest, and the honest reproduction of events, is one of the most difficult and hotly debated topics among documentarists.

The documentary medium is a form of storytelling that persuades the audience to see the subject matter in a particular light. Documentary photography is especially powerful and compelling because of its close association with immediacy and truth. Documentaries can be seen as tools of persuasion in that audiences tend to fall in line with the documentary’s argument. It is not always the documentary photographer, however, who shapes the story.

We do not consider art to be untruthful, but we do understand it to be a deliberately fictional representation of reality.

Photography, because it mechanically reproduces the scene before it, was at first considered to be a method of representation that excluded the artist’s perspective. However, I have thus far shown how photography is an inherently manipulative medium. To call photography untruthful is not correct; a quality of art is that it does manipulate in order to reveal truth, or to show us aspects of the world we normally would never consider. We do not consider art to be untruthful, but we do understand it to be a deliberately fictional representation of reality.

Myth and Meaning Art is often used as a tool by ruling powers to persuade the masses. Often, religious leaders have been the dominant authority figures of a culture, and thus art and religion have a long, entwined history. Art has been used to celebrate various religions throughout the world for centuries. Religious leaders have also used art to strengthen their authority over the populace. Although our post-industrial society prides itself on rationality, our current stories and art make use of many of the same themes as religious mythology. Even our journalism and news photographs rely on this mythic-based dialogue to transmit certain ideas, thoughts, and values. The myths of a modern culture conform to suit the character of the culture, and are often so well disguised that we do not even think of them as “myths.” Every culture has myths, however they merely take on an acceptable shape, changing and adapting to suit a culture’s tastes and standards. Although the superficial details of mythic stories change over the course of time, the underlying meanings remain consistent. These unchanging values of myths are called archetypes: original models after which other things are patterned. Myths are distinctive forms of speech, narratives that are familiar and reassuring to the host culture. Myths are a culture’s way of trying to articulate the core concerns and preoccupations of society. Karl Jung saw mythic archetypes as recurring patterns, or universal blueprints, in the human psyche. Jung stated that our belief in myth is reflected in our dreams, and that by unlocking the mythic code of our dreams we can come to an understanding about our lives. Jung believed that such an understanding could lead to meaning, direction, order and a sense of wholeness. Because myths guide us through human experience common to all, we view them, either consciously or not, as reflecting the deepest truths of life. And perhaps, because myth reflects the unchanging facets of the human experience and human nature, they do represent absolute truths. Postmodernism states that truths change over time because human culture and perceptions change over time, but the existence of myth proves there are some aspects of humanity which remain indifferent to the passage of time.

News & Documentary Photography and Myth The purveyors of myth hold a great deal of influential power within a culture. Previously, the purveyors of myth were almost solely religious authorities. In our more secular society, journalists often fill this role. Through the dispersion of news, journalists tell stories that address societal concerns. Journalists are storytellers in our culture, only they must remain true to real events in their telling, rather than create or transform events as a novelist or movie maker does. Journalists pride themselves on this objectivity, of stating just the facts. When a story is broadcast on a news show, the audience does not usually wonder if the story is true, or whether the journalist is lying. We trust journalists to give us objective information that is relevant to our lives. We also trust that this information is true, because journalists are seen as “news specialists.”

Myth, like news, rests on its authority as “truth.” By accepting journalists as “news specialists,” we believe that the news they relay to us is true and, for the most part, unbiased. As news specialists, journalists themselves fulfill a mythic archetype: the messenger, or communicator. In Greek mythology, the God Hermes represented the messenger archetype; the Roman equivalent was the God Mercury. Because we see mythic archetypes as representations of “the true,” the association between messenger and journalist reinforces our belief that journalism is “the truth.”

On closer inspection, the notion that journalism equals truth does not hold up. For instance, because journalists look for certain elements to carry or propel their story, they cannot be considered wholly objective. Just as fiction uses the different or particular to illustrate universal values, so do news stories. Journalists tend mainly to report on stories that have certain elements, or “news values.”

In other words, journalists, as members of a particular culture, are bound by the “culture grammar” that defines rules of narrative construction, a realization that changes the notion of an “objective” transposing of reality. New Journalism, for instance, uses the devices of fiction in order to tell a compelling news story.

Regular news reporting is not fiction, but it is a story about reality, rather than reality itself. These constructed stories, drawing their themes from myth, give people a schema for viewing the world and for living their lives. The documentary form of journalism, “the creative treatment of actuality,” uses fictional narration devices more freely and overtly than do straight news stories. Documentaries are modes of storytelling that use fictional narrative methods. A narrative consists of causally-linked events that occur at a specific place and time. Documentarists rely on several narrative techniques, such as the ‘a day in the life’ format, the ‘problem – solution’ format, and the ‘journey to discovery.’

News and documentary photography effectively record the texture of current experience, and invest that experience with meaning. Photographs, as stated earlier, are symbolic narratives. But in order for these symbolic narratives to remain effective, the photographs must remain current.

Science Photography and Truth Photography is not only used by journalists and artists, however. Scientists also make wide use of photography’s various applications. Science and truth have a long association, and the modern era was in part defined by a belief in science’s ability to objectively discover absolute truths. Currently, science does not claim to discover final truths, yet scientists are often seen as unquestionable authorities in our technology-driven culture, very similar to the earlier unquestionable authorities of religion. Journalists actually contribute to this image, strengthening the connection between science and authority. Journalists tend to hold scientists in high esteem, and they promote scientists as superstars, super geniuses, or as brilliant eccentrics who operate outside the realm of normal human activity. Science has had a long association with religion. Science and religion generally also share a belief that truth is found or revealed, rather than made, as postmodernists believe. Yet a principal difference between science and religion lies in the search for truth. The common quest of both science and religion is the search for truth and understanding, but religion relies on faith whereas science relies on proof obtained through observation and experimentation.

We put our faith in our scientists, not only because of our belief in the truth of mythological archetypes, but also because science represents the search for truth. We often rely on journalists, our messengers or scribes, to interpret this knowledge for us.

Science and the visual arts have much in common. Both science and the visual arts have an interest in color and light, and both attempt to achieve understanding derived from observation.

Science and the arts may tend to flourish together because practitioners from each field draw from one another for inspiration. Not only can photography make traditionally dull science topics seem artistic, but photography can also make such topics seem exciting. Photography can expand the audience for science by making science both more interesting and accessible.

Just as journalists and scientists disagree on the definition of truth, they also disagree on how to communicate truth. Many scientists object to the literary devices journalists employ in telling a story, for instance. Journalists strive to capture the essence of the science, but scientists expect the “nuts and bolts” of their findings to be expressed as well.

In order for a journalist to have his story read by the public, he must make that story appealing and interesting. Photography aides in this process, giving the public clear pictures to accompany and illustrate the text.

Truth and Beauty One quality of art and photography that is associated with truth is the representation of beauty. One reason beauty and truth are linked is because of beauty’s connection to myth through archetypal patterns. Archetypes can be geometric patterns (such as circles, spheres and triangles) that occur naturally in nature. Artists often use these patterns as signifiers or clues of deeper meaning. Religious art often relies on symbols and patterns to convey meaning and truth. Beauty similarly is associated to truth due to its archetypal representation of order and form. This emphasis on order coincides with the Platonic ideal of beauty, which is based on unity, regularity and simplicity. Plato stated that every living person is in the process of becoming, of moving toward the ideal. The more “beautiful” something is, the more it will be seen as closer to the ideal. The idea that beauty is associated with truth and meaning has long been a basic belief of scientific philosophy.

The Sublime and the Beautiful The Kantian idea of the sublime appears at first glance to be the antithesis of Platonic beauty. Beauty is achievable, pleasurable, and evokes feeling of peace and contentment. The sublime, rather than the opposite of beauty, is instead a higher, less restful form of appreciation. Beauty is calm and surety; the feeling of truth found. The sublime is awe and exhilaration, but also a restless feeling of the need to achieve understanding. The sublime is often connected to beauty, however. Beauty acts as a base from which the sublime is reached. Perhaps what motivates “a search after the beautiful,” or the true, is the sense of the sublime that follows from an appreciation of the beautiful. As stated previously, beauty promotes feelings of peace and satisfaction, of truth found, whereas the sublime promotes the need to search for truth.

Beauty and Photography Beauty is a common theme in science, art, literature and journalism. All these modes of inquiry seek to uncover "truth," and beauty is a way for them to “prove” they were successful in their search. But just as beauty does not always equal scientific truth, it does not define other truths either. The same applies to photographs – beautiful pictures are not inherently any more true than ugly ones. In fact, many beautiful photographs are manipulated, showing a falsified vision of reality. And just as with scientific theories, belief affects whether we see a photograph as beautiful or not.

A photographer who prefers to represent beauty is often seen as someone who irresponsibly depicts the world through rose- colored glasses. National Geographic , for instance, has been accused of only presenting the sunnier side of life due to its preference for strikingly beautiful images. Despite the belief that beauty is a sign of irresponsibility or decadence, most successful documentary photographs can still be considered beautiful in form, even when the subject matter (the content) is ugly. The horror of war is, unfortunately, an undeniable truth about the history of human existence.

In photography, as in other forms of art, simply a beautiful form is not enough to suggest truth or to reveal meaning.

In photography, as in other forms of art, simply a beautiful form is not enough to suggest truth or to reveal meaning. If photographers take a picture simply because the image looks nice, the end result may often be banal rather than beautiful.

A dramatic or beautiful picture will catch the eye, but it often won’t engage the mind unless it is placed in context. This is why, according to Adams, photographers and other artists need a firm grounding in the history of their art to be successful. To be able to reveal meaning in new ways, one must know how meaning has been revealed in the past.

Beauty does not guarantee either truth or meaning. Beauty, like myth, depends on what we as a community believe. Despite the fact that order and symmetry define beauty, we may not acknowledge the ‘beauty’ of an object unless we are willing or ready to do so. This ties our sense of the beautiful inexorably to culture. Postmodern art highlights this culturally-dependant quality of beauty to prove how truth is product of culture. As stated previously, the idea that truth is defined by culture is the position of postmodernist philosophy.

Beauty in Aesthetic Philosophy Modern philosophical theories reflect on the issues of beauty and belief, as well as the issues of symbolism and meaning. One of the differences between modernism and postmodernism has to do with the artistic representation of the sublime. As stated above, the sublime is characterized by boundlessness and formlessness. It is very difficult, if not impossible, to represent the concept of the sublime in a work of art. We can conceptualize the infinitely great and the infinitely small, but all of our attempts to describe or represent such concepts seem inadequate.

In modernism, art involves both the beautiful and the sublime. In postmodern art, however, beauty is eschewed entirely as an outdated, ineffective model. When you consider that postmodernists believe that chaos ultimately wins out over order, this makes perfect sense.

Postmodernism looks down on beauty as nostalgia, or at least as a man-made construct; beauty is, after all, based on belief. Postmodernism instead seeks new forms of presentation, not for enjoyment, but as a means of expressing the unpresentable, the sublime. Postmodernism may have determined its own dead end by stating that the surface is everything. It is no wonder that postmodernism is often characterized by malaise or nihilism; why bother giving anything more than a cursory glance if there is no sense of deeper meaning? Without the symbols of myth, such as beauty, it is possible that a sense of the sublime may never be achieved, and it is the sublime that often prompts a need to search for deeper understanding.

Postmodernism has touched upon most of the fields in the liberal arts, and photography as been especially affected. Both modern and postmodern art promote the idea that images must be decoded. In modernism, this decoding is achieved by understanding a language of symbols or signs that indicate deeper meanings. Postmodernism says photographs need to be decoded according to their relationships to other factors within the culture. Whereas modernism treats a photograph as an image containing meaning, postmodernism sees a photograph as a cultural object.

Photography, as stated previously, is a manipulated medium, despite the protestations by news photographers of complete objectivity. The photographer chooses his subjects, frames his pictures, and alters the appearance of the photograph in the darkroom. He creates according to his own personal vision and aesthetic taste. This fact alone would seem to negate the postmodernist viewpoint, however, postmodernists claim that which we take as individual taste is a product of culture, any subjective aspects photographers believe they have infused in a photograph are really only borrowed from a pre-existing pool of ideas.

Although the postmodernist viewpoint currently prevails in most of the critical literature on photography, I believe there is still room for some of the tenets of modernism in current photographic thinking. The continued efficacy and resonance of mythic archetypes and themes throughout society would seem to indicate that symbols are effective in conveying meaning. The fact that new photographic images continue to capture our interest and even astonish and amaze us seems to suggest that the malaise postmodernists wallow in is not wholly reflective of the attitude expressed by the general public. Originality, genius, and individuality are still possible within a society of shared beliefs, influences and experiences. After all, as stated previously, art often means different things to different people. Although beauty has always been associated with form, order, and symmetry, individual understandings or representations of beauty vary. While the existence of myths suggests there are inherent, universal aspects of human understanding, there are enough differences among us to ensure we may never reach the dead end that postmodernists claim we have already crashed into.

Part of our trust in photography stems from our unconscious faith in mythic archetypes as universal truths.

Conclusion Photographic truth, like all other truths, depends on culture, belief, history, understanding, and human nature. There are truths that change, while others remain constant. The truths that remain constant will most likely reflect basic, unchanging facets of human life, such as of nature and biology, or of how to best cope with the demands of living in society. These unchanging facets are often related through mythic archetypes, and these archetypes are often featured in art works that endure over time. These works of art endure because they capture aspects of our own experiences, perceptions, attitudes and intentions. If they did not fairly reflect our own lives, they probably would not last. But even these unchanging truths are under constant reconsideration. Reality is not static, it is in constant flux, undergoing revision as new aspects of life continually come to light. Part of our trust in photography stems from our unconscious faith in mythic archetypes as universal truths. Myth is a symbolic language reflecting conditions inherent in human culture, and it affects how we see the world and tells us how we should conduct our lives. Although unacknowledged by the conscious mind, myths influence our ideas of what is “true” and guide us down the path toward understanding. Photography speaks in an extremely powerful symbolic language, a language that derives power from its non-verbal, almost subconscious quality. Although news and documentary photographs are not formally considered “artistic” photographs, they best perform the same function as art: by choosing and selecting which aspects of reality to highlight and address, they do away with the trivia and chaff of the day-to-day, and show us in many ways how life may be led and understood. Through manipulation, they reveal truth, or at least, what the photographer perceives to be truth. Our understanding of reality depends on a knowledge and awareness of both the internal and external world. Photography, as both a reflection and a manipulation of reality, is likewise viewed and judged by that vision. It is only by understanding why photography is so closely aligned with truth that we can come to comprehend our own deep-rooted faith in its authenticity.

you can download the complete thesis here

Additional reading

Cindy Sherman in Photo Elysee

The consolation of radiant lightness

The Riga Photography Biennial 2024 focuses on identity issues

Join our subscribers list to get the latest news, updates and special offers delivered directly in your inbox.

TRUTH IN PHOTOGRAPHY

A new platform explores the ongoing dialogue around photography, social change, and the shifting role of media

TRUTH IN PHOTOGRAPHY is a new interactive platform looking into the history of image-making through the work of renowned artists, lesser-known practitioners and vernacular photography. Magnum Photos will be collaborating with Alan Govenar, curator and founder of the platform, to provide content drawn from the archives as well as contemporary work that will interrogate the nature and intentions of the medium.

Here, Magnum’s Cultural Director Pauline Vermare discusses the project with Govenar. The first edition of TRUTH IN PHOTOGRAPHY features two Magnum bodies of work, Nanna Heitmann’s reportage on Covid-19 in Russia, and a group portfolio on the US/Mexico border – images from both illustrate this interview. You can explore the platform here .

Pauline Vermare: You have been building this encyclopedic project for a long time now. It is made of layers and layers of content – not only photographs but also video, audio, text… This is an impressive combination of knowledge that amounts to years of research and critical thinking. Can you tell us more about the nature of the platform, and your intentions for it?

Alan Govenar: TRUTH IN PHOTOGRAPHY is an open-ended forum for active dialogue and discussion about photography and social change, exploring the issues vital to truth in image-making that are crucial to our world today. This interactive project questions the singular truth of photography by presenting multiple points of view, featuring diverse curators, photographers, critics, and historians, and integrating vernacular photography, photojournalism, and fine art photography. TRUTH IN PHOTOGRAPHY continues the work of Documentary Arts, a Texas- and New-York-based non-profit organization I founded in 1985 to present essential perspectives on historical issues and contemporary life.

What was your thought-process around the selection of different themes explored on the site?

The themes we focus on are historical and contemporary, timely and timeless. They are not definitive but are instead points of emphasis and comprehensive in different ways. Clearly, photographers in today’s world are broadly engaged in many, if not all, of these themes. Some of themes we intend to explore include: Looking for Truth in a Digital Age; The Ethics of Truth; Community and Cultural Identity; The Democratization of the Camera; The Transmission of Photographic Truth; The Manipulation of Photographic Truth; The Professionalism of Photography; Advocacy for Social Change; Concerned Photography; Citizen Journalism; and The Power of Abstraction to Reveal Truth. As TRUTH IN PHOTOGRAPHY evolves, new themes will emerge, offering windows into the thinking and creative process of photographers as the scope of their work expands.

One of the great appeals of the platform is the juxtaposition you create between archival and contemporary work, and between professional and vernacular photography, which really exemplifies the breadth and depth of what photography is – what it means for the photographers, what it means for the subjects, what it means for the viewers. For the launch of the platform and this first edition, you have curated two essays by Magnum photographers: one is Nanna Heitmann’s Covid-19 work, which is accompanied by an interview. Can you tell us about that?

Nanna Heitmann’s photo-essay is an intimate portrayal of the intensity of Covid-19 in and around Moscow, from photographs of congregants at a Russian Orthodox Church that echo the compositions and coloration of Bruegel paintings to haunting, yet gentle, portraits of frontline medical workers and the stark reality of hospital patients. In my Zoom interview, Nanna speaks with humility and candor about the difficult truths and ethical challenges of documenting the suffering she witnessed. Her comments are at once compelling and poignant.

The core idea and mission of the platform is to be open and diverse, engaging photographers, curators, editors, academics of all backgrounds to take part in the narrative. Can you tell us more about the intended participatory nature of the project?

At this point, the site encourages submissions in two different ways. The first is our Share Your Truth page, where anyone can submit an image by uploading it, and then filling out a description of the image and answering the question “How does the image express or manipulate truth?” The second way to submit to Truth in Photography is to view our submissions page. There you can fill out a contact form to let us know how you would like to contribute to the site.

In addition, there is an opinion section, where anyone can give their perspective by finishing the sentence “Truth in photography is…”

Our collaborators – Magnum Photos, Aperture Foundation, International Center of Photography, Local Learning, Family Pictures, and others (museums, libraries, schools, colleges, cultural organizations and the general public) — will help shape our curatorial direction in the development, design, and content. With each edition of our open-ended forum, we hope to add partners and collaborators.

Most of the projects you have led until now had a very strong educational dimension to them. What about this one?

The site explores the ways in which the truth in photography has been debated and challenged, delving into current issues, but also those from the past. As the site evolves, it will become a multimedia encyclopedia of photography that strives for gender and cultural balance, reflecting the diversity of image-makers from around the globe. Every edition of TRUTH IN PHOTOGRAPHY will include historical content that delves into the way image-making developed into what it is today, and how the issue of truth has been central to the medium from the very beginning. In addition, TRUTH IN PHOTOGRAPHY will be a multifaceted resource, containing many links to other websites, essays, articles, blogs, and books, which elaborate the context of the featured photo-essays and provide opportunities for continued learning. We are working with teachers and community educators to develop learning resource materials. Documentary Arts has a long-standing commitment to educational outreach. Our websites www.documentaryarts.org , www.mastersoftraditionalarts.org , everydaymusiconline.org and museumofstreetculture.org offer learning resource guides free of charge.

Theory & Practice

Palermo Gilden

Bruce gilden, explore more.

Completely Half, A Music Video by Bieke Depoorter

Philip Jones Griffith’s Dark Odyssey

Philip jones griffiths.

Exploring Istanbul Through Emin Özmen’s Lens

The Coles of Tomorrow

Behind Bruce Gilden’s Portraits

What to Do If You Are Stuck in a Creative Rut

Back to the Archive, Looking for Peace with Newsha Tavakolian

Famous Faces From the Darkroom

Past Square Print Sale

Conditions of the Heart: on Empathy and Connection in Photography

Magnum photographers.

Photographic truth and documentary photography

Does a photograph represent “truth?” What makes it truthful? When is it untruthful? If it does convey truth, whose truth is it? These questions have been with photography since its origins. They have become more pressing with the advent of digital photography and the ease with which a digital image can be manipulated. They are especially important for those of use who think of ourselves as working in the journalistic and documentary traditions of photography.

I recently re-read Jerry L. Thompson’s book of essays, Truth and Photography: Notes on Looking and Photographing . The following reflections are drawn in part from his opening essay by that title.

Early in its history photography was often seen as an objective representation of reality. It was a “true,” scientific, representation of the world. So for early photographers, truth meant verisimilitude: that is, truth meant that that the picture looked exactly like what would be seen from the camera’s view (with one eye closed since the ordinary camera doesn’t have stereo vision).

Before long, however, self-reflective viewers and photographers began to realize that even the literal image had a subjective element. In addition to the abstraction generated by seeing the world in black-and-white, what photographers chose to photograph, and what they chose to include in the photograph – how it was framed – was highly subjective. As Thompson says, it was a view from a particular point of view.

So although early documentary photographers claimed to objectively represent the world’s realities, they soon became more self-aware, acknowledging that documentary photography had an interpretive and even artful dimension to it.

By the end of the 19th century and through much of the 20th, artistic expression became for many photographers the motivation for photography, and this affected even the documentary tradition. The photographer’s goal was to express the her or his response to the world, to “express your creative vision” as so many camera ads have proclaimed. The photographer’s goal in this view is not to directly copy something but to convey the subjective experience of the subject or the photographer’s mastery of it. Sometimes, in fact, the subject itself is unimportant but is used to convey a personal vision that might have nothing directly to do with the actual subject. What is being documented is the photographer’s experience or impression of the subject.

Thompson analyzes Walker Evans’ photographs from the 1930s. Although apparently they are straight, “documentary” photographs of buildings and people, they are in fact highly personal. In fact, Walker saw them as projections of himself. For Alfred Steiglitz during the same era, truth was his own emotional state and the true artist mastered the medium to shape the image in a way that conveyed his or her own truth. In these views, then, truth means “fidelity to the subjective experience of the artist.”

So photography, Thompson notes, moves between descriptive and expressive approaches. Yet even the descriptive photograph is highly subjective and could depart substantially from “objective” reality.

The lines between these two poles are blurred in the work of Pedro Meyer, Truth & Fictions: a journey from documentary to digital photography. In her introduction to the book, Joan Fontcuberta argues that only a myotic view of documentary work would exclude Meyer’s approach. She gives an example of such a dictionary definition: “Documentary photographs are thought of as those in which the events in front of the lens (or in the print) have been altered as little as possible from what they would have been, had the photographer not been there….” Sometimes Meyer, a Mexican photographer, does not make any alterations in the photos he presents: “…they ae perfect instances of found paradoxical situations….” But often Meyer invisibly manipulates and adds to photographs, creating a fantasy world in which it is difficult to distinguish what was actually there. They are presented as a kind of document, but one that calls attention to the blurred lines between fact and fiction. What is “real” and what is not? Fontcuberta calls on artists to “seed doubt, destroy certainties, annihilate convictions….”

Thompson points out for many photographers – whether their intent isdescriptive or expressive – truth depends on the vision and mastery of the photographer. Thompson is encouraged by the alternate possibilities suggested by a famous Walker Evans portrait in which the subject asserts her own “…overwhelming presence, a ravishing mystery that…delivers a gift, a gift of sight.” “The kind of large, open truth I am trying to attach to photography reaches back toward this initial, primordial sense of wonder, of awe.” So photography as mastery is not the only way to conceive photography. As I have argued before, a photograph depends upon a kind of collaboration between photographer and subject. Sometimes the subject takes, or is given, power in the relationship.

Mastery of the photographic medium has led present-day photography to its “truth,” Thompson acknowledges, but another broader truth endures and asserts itself from time to time in what he calls “genuine encounters.” In my words, when the subject is genuinely respected and allowed to be co-creator with the photographer. “If, at the start of the twentieth-first century, photography still has any unspent capital left, it may be that its greatest reserves will be found in this direction….”

What Is Photographic Truth?

Photography struggles with truth as a concept. With other art forms, truth is generally a non-issue. We do not question whether a painting is real. We do not question whether a dance is real. We are generally able to discern fictional texts from nonfiction; furthermore, we’re generally able to sift through multiple nonfiction texts and combine them with our own experiences to arrive at a conclusion of truth. But not with photography.

Given the mechanical nature of photography, a real-world event had to have existed for you to either take (or make) an image of it. As an aside, taking an image means the act of going out, seeing an event, and taking what’s unfolded before you. Making, in contrast, is when you’ve made the event in front of your camera (whether that’s as simple as directing your friends to say “cheese” at the barbecue before making their image or something more elaborate, like sourcing clothing, hair, makeup, etc. for a fashion shoot).

I digress. If you imagine a thing, you can’t just take a photograph of it. You first have to actually have some semblance of that thing in front of you to make (or take) the photograph. If I imagine an image of a boat, I can just paint a boat. If I imagine a song about a girl, I can just write the song. But if I imagine a specific image of a boat or a girl, I need those things to actually exist in front of my camera in a way I imagined them for me to make a photographic image of them. In this way, photography is mechanically grounded in reality (to an extent).

Self Portrait as a Drowned Man

In Self Portrait as a Drowned Man (1840), Hippolyte Bayard used makeup, props, and posing to pass off as a dead man (when he was not actually dead). He wrote an accompanying statement to the photograph, which furthered his false claim. Photography is mechanically entrenched in the real world. You cannot take a picture of something that is not actually there. Bayard had to make himself look dead.

To reiterate, photography differs from other arts. You can paint whatever you can imagine. You can write whatever you can think of. But with photography, you need at least a real-world form of what you are photographing.

Before the invention of Photoshop (and even before the invention of cameras that could feasibly take portraits outdoors), Constance Sackville-West painted fantastic scenes and then collaged studio images of her family photos into them. Given the limitations, this is a very rudimentary Photoshopping of her time. I don’t think anyone today would question that these people are actually outdoors.

Bayard and Sackville-West are just two such examples of creatives who used photography in a manner that challenges truth while photography was still in its infancy. There are innumerable other examples both new and old.

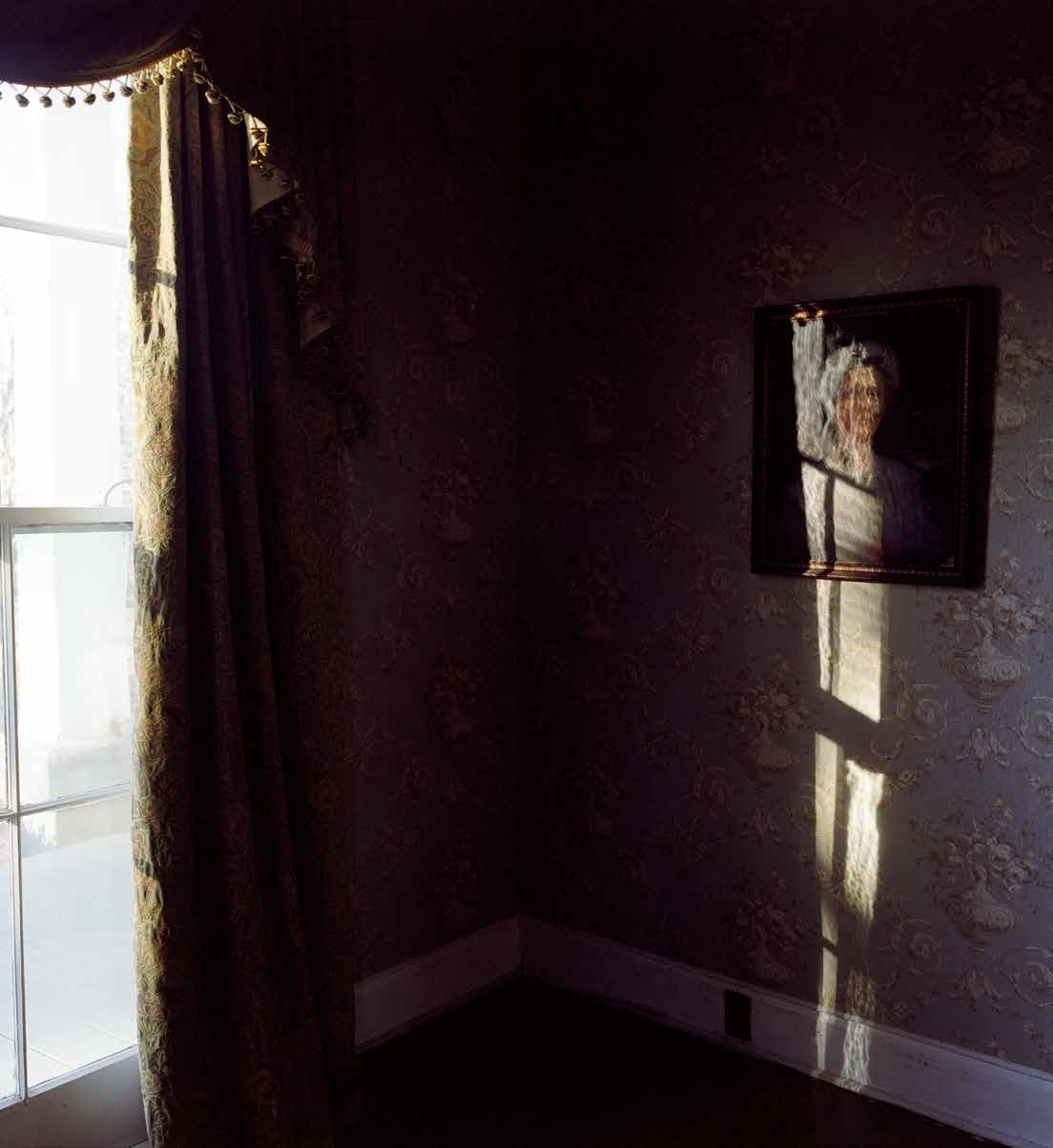

The above image was co-authored with my friends Briarna and Frank as an exercise in creating sunlight. Except for a few minor tweaks by way of color grading, the image is very much straight out of the camera.

This is a studio image and is lit with multiple flashes, some of which had colored gels on them, as well as various reflectors and gobos. The image is indoors, and there is no natural light. The model is not drunk. However, these things seem true because of how the image is staged and lit. In order to create the image, we had to actually stage and light it in a way we had imagined. Although what you see actually existed for the image to be made, none of it is real in the sense that none of it is authentic.

The Next Camera

"Stephen Mayes' "The Next Revolution in Photography Is Coming argues that current digital cameras create images of what is physically in front of them. In order to create a better image, these cameras photograph only a small portion of what is there, instead of having been coded to use algorithms to fill in the blanks.

Since the time Mayes wrote that article, we also have additional augmented photographic techniques more readily available, such as photogrammetry. In this photogrammetric tiki image, I took a whole bunch of images of this little tiki from all different angles. And then, I ran them through specialized software, which created a simulated 3-D model of the tiki. I can turn this around and look at all the nooks and crannies from any side of the computer. If I wanted to be clever, I could use a 3D printer to make a replica of it.

But is the image real? That is to say, this model isn’t a mechanical 1:1 replication of the tiki. It’s what the computer code put together from a bunch of pictures. Even if I printed it, it would be several iterations from the original model and the 3D-printed object.

Mirrors and Windows

In his 1978 essay, “Mirrors and Windows,” John Szarkowski talks about various dichotomies which exist in photography. Romantic or realist. Straight or synthetic. Szarkowski concludes that we are able to describe where a photograph — or body of work — exists on these continuums and that that placement is a factor of and factored by several factors. Ultimately, this placement is a descriptive one and not a prescriptive one.

Szarkowski concludes his essay with the question of the concept of what a photograph — and I guess photography — aspires to be: “is it a mirror, reflecting a portrait of the artist who made it, or a window, through which one might better know the world?”

I would argue that ultimately, it doesn’t matter. I don’t think you’ll have ever had a photograph which is just one or the other, and one or the other isn’t necessarily better or worse. But I believe that the framework in which a photograph is meant to be viewed is more important.

An image can be factual, but not be true. Inversely, an image can be false but still represent the truth.

To clarify, truth isn't necessarily fact. And a factual image may not be true.

As an example, my image of glasses (above), I'd argue, isn't true. They are indeed glasses. The image was lit and photographed as it was. But unless you looked closely (or I told you), you would not know they are doll glasses. And in that, the image warps reality in a way photography does so well. Photography has the power to upend truth. It is factual — and unaltered an image as can be (save for a few tweaks to color).

The clarification here (and perhaps one I should have made earlier in this article) is that truth and fact are not the same things. The image exists as a fact. I actually did have toy glasses on a pink piece of paper. I actually put lights on them and pressed the button on the camera. This is factually true. But the truth of the image, which I won’t go into detail about, is one of commentary on consumption and materialism.

Conversely, my image of Lucien may not necessarily be fact. But it is a mirror to the truth. You can behold it and feel a certain something. Or perhaps not. It reflects an emotional truth, despite being a constructed image.

Here, "constructed" means that I didn’t actually just catch him in my studio like that. It wasn’t happenstance, but rather, he was invited, and this was a concept we had discussed in advance. But either way, he doesn’t leave trails of light as he moves. That was a decision that was executed on camera to speak to an emotional truth.

The onus of Mayes’ claim rests on an inherent truth in photography, or at least that photography has more of an inherent truth than an image created from computing coding and algorithms.

Since its invention, photography has never been true. Photography is lies. An image of a thing is just that: an image. It is not the thing itself. Bayard clearly proves that with a bit of figurative smoke and mirrors, you can quite literally take a photograph that lies.

This leaves us with the question of the photograph as perhaps a mirror to the truth.

Ali Choudhry is a photographer in Australia. His photographic practice aims to explore the relationship with the self, between the other, and the world. Through use of minimalist compositions and selective use of color and form he aims to invoke what he calls the "breath". He is currently working towards a BA (Honours) in Photography.

This is a great article. Because of the inherent mechanical aspect of photography in general it has often been looked down upon by the "art" world. Using a computer program to manipulate images intensifies the disconnect seen by "traditional" artists.

Thanks Glenn! And I agree completely. I'm also weary of this "digital art" craze; but we'll see.

University of Notre Dame

Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews

- Home ›

- Reviews ›

Photography and Philosophy: Essays on the Pencil of Nature

Scott Walden (ed.), Photography and Philosophy: Essays on the Pencil of Nature , Blackwell Publishing, 2008, 325pp., $79.95 (hbk), ISBN 9781405139243.

Reviewed by John Andrew Fisher, University of Colorado at Boulder

Shows devoted to photography seem to be everywhere in the art world. As Scott Walden, the editor of this collection of essays notes, photography "has become the darling of the avant-garde." It appears that photography has become trendier than painting. One reason for this may be that while the nature and scope of painting has been thoroughly investigated over the last two centuries, photography appears to be relatively unexplored. Moreover, as a medium photography has the advantage over both painting and sculpture of permeating social life and thus of appearing to be easier to understand in an art-world setting than other art forms. In addition, the variety of uses of photography in everyday life -- portraits, snapshots, fashion and advertising photographs -- provide artists with a multitude of genres to explore and often parody.

Perhaps surprisingly then, only a few of the thirteen essays that make up this collection directly address the artistic or conceptual content of current art photography. This is not to say that the collection is in any way disappointing. On the contrary, it is a ground-breaking, cutting-edge anthology of essays by leading analytic philosophers of art all focused in one way or another on the foundations of photography. In his contribution to the collection, Walden elaborates on his focus on truth in images with an explanation that could also serve as a rationale for the entire collection:

the operative assumption here is that the best methodology for understanding our appreciation of pictures involves first developing an understanding of their most literal aspects, and then proceeding to an understanding of the more complex aspects in terms of these relatively simple ones… . The faith is that if we can understand truth in relation to the depiction of the simple, visible properties of people and objects depicted, we can then, in terms of these and some other -- as yet undetermined -- principles governing the viewing of pictures, arrive at a more comprehensive understanding of the use of images in journalism, advertising, illustration, and art. (p. 94)

This faith might seem debatable, but in fact these essays do indirectly illuminate photography as art even when that is not their primary goal. By undermining the complacency with which we approach a mass art medium, they indirectly address the central aesthetic question that arises in looking at art photography: "In what ways can I appreciate a photograph aesthetically?"

Why does photography merit extended philosophical examination? Few other art media have troubled art theorists as much as photography, and this has been true since its inception in the nineteenth-century. Only instrumental classical music has fascinated philosophers as much. In pure instrumental music there is no intrinsic representational content, yet the music feels as if it is saying something and sounds as if it expresses emotions. In the case of photography we have the opposite problem: instead of too little representation, we have nothing but pure representation; we see nothing in a photograph but the objects that are photographed.

There are four fundamental issues that underlie the more specific themes of these essays: (i) What is the nature of photography? (ii) Given this nature, can photographs as photographs be fine art? (iii) How does photographic representation differ from other types of visual representation? and (iv) In what way are photographs more realistic, objective or true than representations produced in more traditional media?

Most of the papers were written especially for this anthology, although three chapters are reprints of papers by prominent figures in analytic aesthetics (Kendall Walton, Roger Scruton, Arthur Danto). Two of these papers, Walton's "Transparent Pictures: On the Nature of Photographic Realism," and Scruton's "Photography and Representation," are classics and serve to anchor the anthology by providing influential albeit controversial accounts of the foundations of photography. Walton argues that photographs are 'transparent,' by which he means that in looking at photographs we "quite literally" see their subjects. Scruton argues that a photograph cannot be what he calls a "representation," and by this he intends to imply that it cannot qua photograph be a work of art. To make their arguments, these two thinkers develop extended analyses of concepts central to photographs: in Walton's case, the concepts of seeing and visual experience, and in Scruton's case, the concept of an artistic representation. In relating photography to more general concepts, these papers join several others in the anthology. For example, Danto argues that individuals have rights over the way they appear, a meditation spawned by what he regards as untruthful photographic portraits.

Although the anthology is not divided into sections, one can collect most of the articles into three main groupings. The first group consists of five articles, all directed at analyses of the realism, objectivity, and truth that we attach to photographs: Walton on the transparency of photography, Cynthia Freeland on icons, Aaron Meskin and Jonathan Cohen on evidence, Walden on truth and Barbara Savedoff on authority. Danto's contribution, "The Naked Truth," also explores the specific sort of truth that might be ascribed to photographic portraits. He proposes a distinction between the optical truth that a high-speed photograph, which he calls a 'still,' might reveal and the natural way we see people or things. He argues that the "still … shows the world as we are not able to perceive it visually. It shows us the world from the perspective of stopped time" (300). Such photos often lie as portraits, Danto thinks, and when they do, they violate the personhood of the subject by failing to respect the image the subject desires to project to the community.