Ethics and Pandemics pp 61–83 Cite as

Utilitarianism and Consequentialist Ethics: Framing the Greater Good

- Andrew Sola 4

- First Online: 24 June 2023

367 Accesses

Part of the book series: Springer Series in Public Health and Health Policy Ethics ((SSPHHPE))

This chapter evaluates the most important alternative to Kantian deontology: utilitarianism, the idea that we should pursue the greatest possible happiness even if doing so infringes on other people’s rights. Both the advantages and disadvantages of the theory are discussed. Three interdisciplinary perspectives are offered. The first explores the problem of equitable vaccine distribution by discussing the Fair Priority Model for Vaccine Distribution. The second interdisciplinary perspective addresses the ethical problem of quantifying human life and medical treatments while assessing the strengths and weaknesses of utilitarian cost-benefit analysis. The final interdisciplinary perspective introduces readers to the history of smallpox. The eradication of the disease is one of the great triumphs of medical history. However, the discovery of the smallpox vaccine is founded on a great problem: The first test subject was the 8-year-old son of Edward Jenner’s gardener. Readers are encouraged to assess Jenner’s action, as well as compulsory vaccination policies. The chapter concludes by asking readers to perform a self-assessment. Given the two major ethical theories discussed—Kantian deontology and utilitarian consequentialism—which seems to be best equipped to deal with pandemic dilemmas?

- Utilitarianism

- Consequentialism

- Vaccine equity

- Healthcare economics

- Edward Jenner

- Vaccination

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Peter Singer has consistently argued that people in wealthy countries should donate their money to the poorest places on this planet since a dollar goes much further in, say, alleviating hunger in a developing nation than it does in a wealthy nation.

When you donate to charity, the universal law you are creating would be as follows: “All people should donate to charity.”

Bentham, J. (1789). An introduction to the principles of morals and legislation . Econlib. 2018. https://www.econlib.org/library/Bentham/bnthPML.html

DOT. (2021, March 23). Departmental guidance on valuation of a statistical life in economic analysis. https://www.transportation.gov/office-policy/transportation-policy/revised-departmental-guidance-on-valuation-of-a-statistical-life-in-economic-analysis . Accessed 1 Sept 2022.

Emanuel, E. J., et al. (2020). An ethical framework for global vaccine allocation . Science 10.1126. https://philpapers.org/archive/EMAAEF-2.pdf

EPA. (2022, March 30). Mortality risk valuation. https://www.epa.gov/environmental-economics/mortality-risk-valuation . Accessed 1 Sept 2022.

Gandjour, A. (2020). Willingness to pay for new medicines: A step towards narrowing the gap between NICE and IQWiG. BMC Health Services Research, 20 , 343. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-5050-9

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hume, D. (1748). An enquiry concerning human understanding . Project Gutenberg. 2011. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/9662/9662-h/9662-h.htm

Jecker, N. S. (2021, September 17). Are COVID-19 boosters ethical, with half the world waiting for a first shot? A bioethicist weighs in. The Conversation . https://theconversation.com/are-covid-19-boosters-ethical-with-half-the-world-waiting-for-a-first-shot-a-bioethicist-weighs-in-167606 . Accessed 18 Oct 2021.

Kant, I. (1795). Perpetual peace: A philosophical sketch . Project Gutenberg. 2016. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/50922/50922-h/50922-h.htm

McCloskey, H. J. (1965). A non-utilitarian approach to punishment. Inquiry, 8 , 239–255.

Article Google Scholar

Mill, J. S. (1863). Utilitarianism . Project Gutenberg. 2004. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/11224/11224-h/11224-h.htm

Mill, J. S. (1873). Autobiography . Project Gutenberg. 2018. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/10378/10378-h/10378-h.htm

Neumann, P. J., Cohen, J. T., & Weinstein, M. C. (2014). Updating cost-effectiveness—The curious resilience of the $50,000-per-QALY threshold. New England Journal of Medicine, 371 , 796–797. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1405158

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Rachels, J., & Rachels, S. (2012). The elements of moral philosophy (7th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Google Scholar

Schuessler, J. (2021, September 11). Peter Singer wins $1 million Berggruen Prize. The New York Times . https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/07/arts/peter-singer-berggruen-prize.html . Accessed on 11 Sept 2021.

Singer, P. (1975). Animal liberation: A new ethics for our treatment of animals . Harper Collins.

Singer, P. (1999, September 5). The singer solution to world poverty. New York Times Magazine . https://www.nytimes.com/1999/09/05/magazine/the-singer-solution-to-world-poverty.html . Accessed 28 Aug 2022.

Singer, P. (2000). Writings on ethical life . Harper Collins.

Singer, P. (2009). The life you can save: Acting now to end world poverty . Random House.

Snowden, F. M. (2019). Epidemics and society: From the black death to the present . Yale UP.

Book Google Scholar

UK Health Security Agency. (2021, May 19). Economic evaluation: Health economic studies. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/economic-evaluation-health-economic-studies . Accessed 10 Sept 2022.

UN. (2021). No poverty: End poverty in all its forms everywhere. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2021/goal-01/ . Accessed 28 Aug 2022.

WHO. (2021). Vaccine equity campaign. https://www.who.int/campaigns/vaccine-equity . Accessed 28 Aug 2022.

World Bank. (2018, October 17). Press Release. Nearly half the world lives on less than $5.50 a day. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2018/10/17/nearly-half-the-world-lives-on-less-than-550-a-day . Accessed 5 Dec 2021.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Amerikazentrum, e.V., FOM University of Applied Sciences, Hamburg, Germany

Andrew Sola

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Sola, A. (2023). Utilitarianism and Consequentialist Ethics: Framing the Greater Good. In: Ethics and Pandemics. Springer Series in Public Health and Health Policy Ethics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-33207-4_4

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-33207-4_4

Published : 24 June 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-33206-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-33207-4

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

5 Utilitarianism: Theory and Applications

- Published: October 2002

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Utilitarianism is a comprehensive doctrine claiming that the greatest amount of happiness is an end that should exclusively guide all actions of both government and individuals. The fact that people value the happiness of those close to them more than that of strangers makes utilitarianism personally unacceptable to many, but it may still be a proper principle for government, given some overriding respect for individual rights. There are, however, basic problems concerning the value of life, and the treatment of future people and foreigners. The conventional discounting of future incomes does not imply that the utility of future people is discounted. The state's primary responsibility is to its own citizens, but it should not treat aliens as mere instruments for the welfare of citizens.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

5 Utilitarianism

Frank Aragbonfoh Abumere

Introduction

Let us start our introduction to utilitarianism with an example that shows how utilitarians answer the following question, “Can the ends justify the means?” Imagine that Peter is an unemployed poor man in New York. Although he has no money, his family still depends on him; his unemployed wife (Sandra) is sick and needs $500 for treatment, and their little children (Ann and Sam) have been thrown out of school because they could not pay tuition fees ($500 for both of them). Peter has no source of income and he cannot get a loan; even John (his friend and a millionaire) has refused to help him. From his perspective, there are only two alternatives: either he pays by stealing or he does not. So, he steals $1000 from John in order to pay for Sandra’s treatment and to pay the tuition fees of Ann and Sam. One could say that stealing is morally wrong. Therefore, we will say that what Peter has done— stealing from John—is morally wrong.

Utilitarianism, however, will say what Peter has done is morally right. For utilitarians, stealing in itself is neither bad nor good; what makes it bad or good is the consequences it produces. In our example, Peter stole from one person who has less need for the money, and spent the money on three people who have more need for the money. Therefore, for utilitarians, Peter’s stealing from John (the “means”) can be justified by the fact that the money was used for the treatment of Sandra and the tuition fees of Ann and Sam (the “end”). This justification is based on the calculation that the benefits of the theft outweigh the losses caused by the theft. Peter’s act of stealing is morally right because it produced more good than bad. In other words, the action produced more pleasure or happiness than pain or unhappiness, that is, it increased net utility.

The aim of this chapter is to explain why utilitarianism reaches such a conclusion as described above, and then examine the strengths and weaknesses of utilitarianism. The discussion is divided into three parts: the first part explains what utilitarianism is, the second discusses some varieties (or types) of utilitarianism, and the third explores whether utilitarianism is persuasive and reasonable.

What is Utilitarianism?

Utilitarianism is a form of consequentialism. For consequentialism, the moral rightness or wrongness of an act depends on the consequences it produces. On consequentialist grounds, actions and inactions whose negative consequences outweigh the positive consequences will be deemed morally wrong while actions and inactions whose positive consequences outweigh the negative consequences will be deemed morally right. On utilitarian grounds, actions and inactions which benefit few people and harm more people will be deemed morally wrong while actions and inactions which harm fewer people and benefit more people will be deemed morally right.

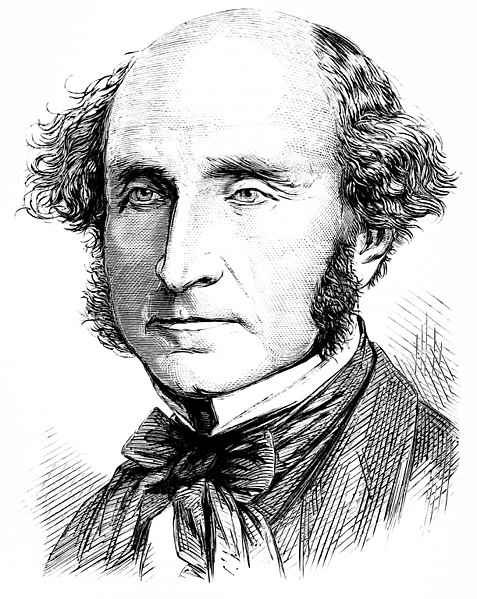

Benefit and harm can be characterized in more than one way; for classical utilitarians such as Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) and John Stuart Mill (1806-1873), they are defined in terms of happiness/unhappiness and pleasure/pain. On this view, actions and inactions that cause less pain or unhappiness and more pleasure or happiness than available alternative actions and inactions will be deemed morally right, while actions and inactions that cause more pain or unhappiness and less pleasure or happiness than available alternative actions and inactions will be deemed morally wrong. Although pleasure and happiness can have different meanings, in the context of this chapter they will be treated as synonymous.

Utilitarians’ concern is how to increase net utility. Their moral theory is based on the principle of utility which states that “the morally right action is the action that produces the most good” (Driver 2014). The morally wrong action is the one that leads to the reduction of the maximum good. For instance, a utilitarian may argue that although some armed robbers robbed a bank in a heist, as long as there are more people who benefit from the robbery (say, in a Robin Hood-like manner the robbers generously shared the money with many people) than there are people who suffer from the robbery (say, only the billionaire who owns the bank will bear the cost of the loss), the heist will be morally right rather than morally wrong. And on this utilitarian premise, if more people suffer from the heist while fewer people benefit from it, the heist will be morally wrong.

From the above description of utilitarianism, it is noticeable that utilitarianism is opposed to deontology, which is a moral theory that says that as moral agents we have certain duties or obligations, and these duties or obligations are formalized in terms of rules (see Chapter 6). There is a variant of utilitarianism, namely rule utilitarianism, that provides rules for evaluating the utility of actions and inactions (see the next part of the chapter for a detailed explanation). The difference between a utilitarian rule and a deontological rule is that according to rule utilitarians, acting according to the rule is correct because the rule is one that, if widely accepted and followed, will produce the most good. According to deontologists, whether the consequences of our actions are positive or negative does not determine their moral rightness or moral wrongness. What determines their moral rightness or moral wrongness is whether we act or fail to act in accordance with our duty or duties (where our duty is based on rules that are not themselves justified by the consequences of their being widely accepted and followed).

Some Varieties (or Types) of Utilitarianism

The above description of utilitarianism is general. We can, however, distinguish between different types of utilitarianism. First, we can distinguish between “actual consequence utilitarians” and “foreseeable consequence utilitarians.” The former base the evaluation of the moral rightness and moral wrongness of actions on the actual consequences of actions; while the latter base the evaluation of the moral rightness and moral wrongness of actions on the foreseeable consequences of actions. J. J. C. Smart (1920-2012) explains the rationale for this distinction with reference to the following example: imagine that you rescued someone from drowning. You were acting in good faith to save a drowning person, but it just so happens that the person later became a mass murderer. Since the person became a mass murderer, actual consequence utilitarians would argue that in hindsight the act of rescuing the person was morally wrong. However, foreseeable consequence utilitarians would argue that—looking forward (i.e., in foresight)—it could not be foreseen that the person was going to be a mass murderer, hence the act of rescuing them was morally right (Smart 1973, 49). Moreover, they could have turned out to be a “saint” or Nelson Mandela or Martin Luther King Jr., in which case the action would be considered to be morally right by actual consequence utilitarians.

A second distinction we can make is that between act utilitarianism and rule utilitarianism. Act utilitarianism focuses on individual actions and says that we should apply the principle of utility in order to evaluate them. Therefore, act utilitarians argue that among possible actions, the action that produces the most utility would the morally right action. But this may seem impossible to do in practice since, for every thing that we might do that has a potential effect on other people, we would thus be morally required to examine its consequences and pick the one with the best outcome. Rule utilitarianism responds to this problem by focusing on general types of actions and determining whether they typically lead to good or bad results. This, for them is the meaning of commonly held moral rules: they are generalizations of the typical consequences of our actions. For example, if stealing typically leads to bad consequences, stealing in general would be considered by a rule utilitarian to be wrong. [1]

Hence rule utilitarians claim to be able to reinterpret talk of rights, justice, and fair treatment in terms of the principle of utility by claiming that the rationale behind any such rules is really that these rules generally lead to greater welfare for all concerned. We may wonder whether utilitarianism in general is capable of even addressing the notion that people have rights and deserve to be treated justly and fairly, because in critical situations the rights and wellbeing of persons can be sacrificed as long as this seems to lead to an increase overall utility.

For example, in a version of the famous “trolley problem,” imagine that you and an overweight stranger are standing next to each other on a footbridge above a rail track. You discover that there is a runaway trolley rolling down the track and the trolley is about to kill five people who cannot get off of the track quickly enough to avoid the accident. Being willing to sacrifice yourself to save the five persons, you consider

jumping off the bridge, in front of the trolley…but you realize that you are far too light to stop the trolley….The only way you can stop the trolley killing five people is by pushing this large stranger off the footbridge, in front of the trolley. If you push the stranger off, he will be killed, but you will save the other five. (Singer 2005, 340)

Utilitarianism, especially act utilitarianism, seems to suggest that the life of the overweight stranger should be sacrificed regardless of any purported right to life he may have. A rule utilitarian, however, may respond that since in general killing innocent people to save others is not what typically leads to the best outcomes, we should be very wary of making a decision to do so in this case. This is especially true in this scenario since everything rests on our calculation of what might possibly stop the trolley, while in fact there is really far too much uncertainty in the outcome to warrant such a serious decision. If nothing else, the emphasis placed on general principles by rule utilitarians can serve as a warning not to take too lightly the notion that the ends might justify the means.

Whether or not this response is adequate is something that has been extensively debated with reference to this famous example as well as countless variations. This brings us to our final question here about utilitarianism—whether it is ultimately a persuasive and reasonable approach to morality.

Is Utilitarianism Persuasive and Reasonable?

First of all, let us start by asking about the principle of utility as the foundational principle of morality, that is, about the claim that what is morally right is just what leads to the better outcome. John Stuart Mill’s argument that it is is based on his claim that “each person, so far as he believes it to be attainable, desires his own happiness” (Mill [1861] 1879, Ch. 4). Mill derives the principle of utility from this claim based on three considerations, namely desirability, exhaustiveness, and impartiality. That is, happiness is desirable as an end in itself; it is the only thing that is so desirable (exhaustiveness); and no one person’s happiness is really any more desirable or less desirable than that of any other person (impartiality) (see Macleod 2017).

In defending desirability, Mill argues,

The only proof capable of being given that an object is visible, is that people actually see it. The only proof that a sound is audible, is that people hear it: and so of the other sources of our experience. In like manner…the sole evidence it is possible to produce that anything is desirable, is that people do actually desire it. (Mill [1861] 1879, Ch. 4)

In defending exhaustiveness, Mill does not argue that other things, apart from happiness, are not desired as such; but while other things appear to be desired , happiness is the only thing that is really desired since whatever else we may desire, we do so because attaining that thing would make us happy. Finally, in defending impartiality, Mill argues that equal amounts of happiness are equally desirable, whether the happiness is felt by the same person or by different persons. In Mill’s words, “each person’s happiness is a good to that person, and the general happiness, therefore, a good to the aggregate of all persons” (Mill [1861] 1879, Ch. 4). We may wonder, however, whether this last argument is truly adequate. Does Mill really show here that we should treat everyone’s happiness as equally worthy of pursuit, or does he simply assert this?

Let us grant that Mill’s argument here is successful and the principle of utility is the basis of morality. Utilitarianism claims that we should thus calculate, to the best of our ability, the expected utility that will result from our actions and how it will affect us and others, and use that as the basis for the moral evaluation of our decisions. But then we may ask, how exactly do we quantify utility? Here there are two different but related problems: how can I come up with a way of comparing different types of pleasure and pain, benefit or harm that I myself might experience, and how can I compare my benefit and yours on some neutral scale of comparison? Bentham famously claimed that there was a single universal scale that could enable us to objectively compare all benefits and harms based on the following factors: intensity, duration, certainty/uncertainty, proximity, fecundity, purity, and extent. And he offered on this basis what he called a “felicific calculus” as a way of objectively comparing any two pleasures we might encounter (Bentham [1789] 1907).

For example, let us compare the pleasure of drinking a pint of beer to that of reading Shakespeare’s Hamlet . Suppose the following are the case:

- The pleasure derived from drinking a pint of beer is more intense than the pleasure derived from reading Hamlet (intensity).

- The pleasure of drinking the beer lasts longer than that of reading Hamlet (duration).

- We are confident that drinking the beer is more pleasurable than reading Hamlet (certainty/uncertainty).

- The beer is closer to us than the play, and therefore it is easier for us to access the former than the latter (proximity).

- Drinking the beer is more likely to promote more pleasure in the future while reading Hamlet is less likely to promote more pleasure in the future (fecundity).

- Drinking the beer is pure pleasure while reading Hamlet is mixed with something else (purity).

- Finally, drinking the beer affects both myself and my friends in the bar and so has a greater extent than my solitary reading of Hamlet (extent).

Since, on all of these measures, drinking a pint of beer is more pleasurable than reading Hamlet , it follows according to Bentham that it is objectively better for you to drink the pint of beer and forget about reading Hamlet , and so you should. Of course, it is up to each individual to make such a calculation based on the intensity, duration, certainty, etc. of the pleasure resulting from each possible choice they may make in their eyes, but Bentham at least claims that such a comparison is possible.

This brings us back to the problem we mentioned before that, realistically, we cannot be expected to always engage in very difficult calculations every single time we want to make a decision. In an attempt to resolve this problem, utilitarians might claim that in the evaluation of the moral rightness and moral wrongness of actions, the application of the principle of utility can be backward-looking (based on hindsight) or forward-looking (based on foresight). That is, we can use past experience of the results of our actions as a guide to estimating what the probable outcomes of our actions might be and save ourselves from the burden of having to make new estimates for each and every choice we may face.

In addition, we may wonder whether Bentham’s approach misses something important about the different kinds of pleasurable outcomes we may pursue. Mill, for example, would respond to our claim that drinking beer is objectively more pleasurable than reading Hamlet by saying that it overlooks an important distinction between qualitatively different kinds of pleasure. In Mill’s view Bentham’s calculus misses the fact that not all pleasures are equal—there are “higher” and “lower” pleasures that make it “better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied” (Mill [1861] 1879, Ch. 2). Mill justifies this claim by saying that between two pleasures, although one pleasure requires a greater amount of difficulty to attain than the other pleasure, if those who are competently acquainted with both pleasures prefer (or value) one over the other, then the one is a higher pleasure while the other is a lower pleasure. For Mill, although drinking a pint of beer may seem to be more pleasurable than reading Hamlet , if you are presented with these two options and you are to make a choice—each and every time or as a rule—you should still choose to read Hamlet and forego drinking the pint of beer. Reading Hamlet generates a higher quality (although perhaps a lower quantity) of pleasure, while drinking a pint of beer generates lower quality (although higher quantity) of pleasure.

In the end, these issues may be merely technical problems faced by utilitarianism—is there some neutral scale of comparison between pleasures? If there is, is it based on Betham’s scale which makes no distinctions between higher and lower pleasures, or Mill’s which does? The more serious problem, however, remains, which is that utilitarianism seems willing in principle to sacrifice the interests and even perhaps lives of individuals for the sake of the benefit of a larger group. And this seems to conflict with our basic moral intuition that people have a right not to be used in this way. While Mill argued that the notion of rights could be accounted for on purely utilitarian terms, Bentham simply dismissed it. For him such “natural rights” are “simple nonsense, natural and imprescriptible rights, rhetorical nonsense—nonsense upon stilts” (Bentham [1796] 1843, 501).

Let us conclude by revisiting the question we started with: can the ends justify the means? I stated that as far as utilitarianism is concerned the answer to this question is in the affirmative. While the answer is plausible and right for utilitarians, it is implausible for many others, and notably wrong for deontologists. As we have seen in this chapter, on a close examination utilitarianism is less persuasive and less reasonable than it appears to be when it is far away.

Bentham, Jeremy. (1789) 1907. An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Bentham, Jeremy. (1796) 1843. Anarchical Fallacies. In The Works of Jeremy Bentham, ed. John Bowring. Vol 2. Edinburgh: William Tait.

Driver, Julia. 2014. “The History of Utilitarianism.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2017/entries/utilitarianism-history/

Hooker, Brad. 2016. “Rule Consequentialism.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy , ed. Edward N. Zalta. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/consequentialism-rule/

Macleod, Christopher. 2017. “John Stuart Mill.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy , ed. Edward N. Zalta. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2017/entries/mill/

Mill, John Stuart . Utilitarianism . (1861) 1879. 7th ed. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/11224

Singer, Peter. 2005. “Ethics and Intuitions.” The Journal of Ethics 9(3/4): 331-352.

Smart, J. J. C. 1973. “An Outline of a System of Utilitarian Ethics.” In Smart, J. J. C. and Bernard Williams.

Smart, J. J. C. and Bernard Williams. 1973. Utilitarianism: For and Against . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Further Reading

Hare, R. M. 1981. Moral Thinking. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hooker, Brad. 1990. “Rule-Consequentialism.” Mind 99(393): 66-77.

Scheffler, Samuel. 1988. Consequentialism and Its Critics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sen, Amartya and Bernard Williams, eds. 1982. Utilitarianism and Beyond. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sidgwick, Henry. 1907. The Methods of Ethics. London: Macmillan.

Singer, Peter. 2000. Writings on an Ethical Life. New York: HarperCollins.

Thomson, Judith Jarvis. 1985. “The Trolley Problem.” The Yale Law Journal 94(6): 1395-1415.

Williams, Bernard. 1973. “A Critique of Utilitarianism.” In Smart, J. J. C and Bernard Williams.

- Of course, there may be exceptions to such a rule in particular, atypical cases if stealing might lead to better consequences. This raises a complication for rule utilitarians: if they were to argue that we should follow rules such as “do not steal” except in those cases where stealing would lead to better consequences, then this could mean rule utilitarianism wouldn’t be very different from act utilitarianism. One would still have to evaluate the consequences of each particular act to see if one should follow the rule or not. Hooker (2016) argues that rule utilitarianism need not collapse into act utilitarianism in this way, because it would be better to have a set of rules that are more clear and easily understood and followed than ones that require us to evaluate many possible exceptions. ↵

Utilitarianism Copyright © 2019 by Frank Aragbonfoh Abumere is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Cambridge University Press - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Liberal Utilitarianism—Yes, But for Whom?

In his important paper “Just Better Utilitarianism,” Matti Häyry reminds his readers that liberal utilitarianism can offer a basis for moral and political choices in bioethics and thus could be helpful in decisionmaking. 1 Although I agree with the general defense of Häyry’s liberal utilitarianism, in this commentary, I urge Häyry to say more on who belongs to our moral community. I challenge Häyry’s principle of actual or prospective existence. I also argue that Häyry should say more on human beings at the “margin of life” (such as fetuses and other mindless humans). I claim that debate over whether some form of utilitarianism is superior over other moral theories is not as important as answering the question underlying these issues: Who belongs to our moral community?

Introduction

In his important paper “Just Better Utilitarianism,” Matti Häyry reminds his readers that liberal utilitarianism can offer a basis for moral and political choices in bioethics and thus could be helpful in decisionmaking. 1 Although I agree with the general defense of Häyry’s liberal utilitarianism, in this commentary, I urge Häyry to say more on who belongs to our moral community. I challenge Häyry’s principle of actual or prospective existence. I also argue that Häyry should say more on human beings at the “margin of life” (such as fetuses). I claim that debate over whether some form of utilitarianism is superior over other moral theories is not as important as answering the question underlying these issues: Who belongs to our moral community?

Challenging the Principle of Actual and Prospective Existence

Häyry’s liberal utilitarianism includes the following principle:

“When the moral rightness of human activities is assessed, the imagined needs of non-existent beings who will never come into existence shall not be counted.”

Call this the principle of actual or prospective existence. Häyry adopts this rule to avoid the repugnant conclusion that we must reproduce every time we could have offspring with tolerable lives. This principle is in line with Häyry’s antinatalist view: not having children is both rational and ethical. 2 , 3 Some see this sort of antinatalist conclusion as repugnant or implausible itself, 4 whereas others endorse similar conclusions for somewhat different reasons. 5 , 6

I am not sure whether it is wrong to have children. That is because I am not fully confident that existence is always bad. However, I am confident that nonexistence cannot be bad, so it cannot be wrong not to have children. Thus, abstaining from procreation seems to be the safe option, morally, because you cannot wrong someone who does not exist. Be that as it may, I think we have a reason to reject the principle of actual or prospective existence or, at least, to revise it.

To see this, consider the following case:

A couple wants to have a child. If they procreate now, their child will be sick. She will suffer pain and discomfort through her life. However, if the couple waits a month, they will have a healthy child whose life is much better – overall – than the life of the child who would be conceived earlier. 7

Assuming that the child would be a different child because of different DNA and that the couple has no reason not to wait a month, it seems that they should wait a month. It is better, morally, to have a child whose life is better than one whose life is worse, other things being equal. Based on some of Häyry’s previous work, I assume he agrees. 8

However, if the principle of actual or prospective existence is correct, it might be difficult to claim that the couple should wait and have the child whose life would be better instead of proceeding immediately to have the child whose life would be worse. After all, if they choose not to wait a month and have the sick child instead, the other child would never come into existence. If the other child never comes into existence, then according to the principle, her imagined needs are not to be counted. And if her imagined needs are not counted, it is not obvious why the couple should have waited a month and created the better off-child rather than the worse-off child.

So, to avoid this problem, it could be that the imagined needs of people that never come into existence matter, at least sometimes. More precisely, they matter when one has decided to bring a person into existence.

One might wonder what sort of moral obligations the couple have if they cannot have the healthier child at all. For example, suppose that no matter what they do, any child they have will spend her life in pain. Technically, a child they conceived at a later time would be a different person from one they conceived at an earlier time, because postponing the act of procreation would cause different gametes to unite. Would it be wrong for the couple to procreate?

I think many people would agree that if the life of the child is worth living, the couple does nothing morally wrong in bringing her into existence. And many would say that even if they also agreed that a couple that could bring a healthy child into existence but intentionally chooses to have a sick child instead does do something wrong.

As I see it, Häyry has three options here. He could reject the principle of actual or prospective existence. But that would, it seems, lead to the repugnant conclusion that we should reproduce every time we could have offspring with tolerable lives. Another choice is to simply bite the bullet and accept that it is not morally wrong to create a life that is worse than some other life you could create instead. But this would contradict Häyry’s previous claims. 9 The third option, which I think is the most plausible one, is to revise the principle of actual and prospective existence so that it is not vulnerable to the counter-example raised above.

Here is one friendly suggestion for how to do that, which I call the revised principle of actual or prospective existence :

When the moral rightness of human activities is assessed, the imagined needs of nonexistent beings who will never come into existence shall not be counted unless one has already made the decision to bring a person into existence. If one has decided to procreate, the imagined needs of nonexistent beings should be counted and one therefore has a moral reason to bring the best-off person one can into existence.

So, if the quality of life of those people who never exist does not matter when one has not decided whether to bring any persons into existence, but only when one has decided to bring a person into existence, the principle does not create an obligation to procreate every time one could do so. This would be in line with what Häyry and others have argued or assumed to be true. 10

Do Actual but Mindless Humans Deserve our Moral Consideration?

How we treat mindless humans could also pose a problem for liberal utilitarianism. By mindless humans , I mean beings that are biologically human (that have human DNA) but that are not conscious, such as (at least early) fetuses and brain-dead humans. For simplicity, here my discussion is focused on fetuses.

Häyry does not discuss the ethics of abortion or the moral status of the fetuses in his paper, but he mentions Alberto Giubilini and Francesca Minerva’s now-famous article on the moral permissibility of infanticide. 11 Häyry approaches that article at a more abstract level: his reaction to it was to demand clarity in bioethical arguments 12 and to discuss the possibility of anonymous publishing. 13

I assume Häyry’s position on ethics of abortion has not changed significantly since he started his career in philosophical bioethics. Then, Häyry summarized his view as follows: abortion is morally permissible and should be legally permitted as long as the woman makes the decision while being aware of the consequences of her decision to herself and the fetus. 14

Pro-choice views on the ethics of abortion can, roughly, be based on two kind of arguments: (1) person-denying arguments and (2) bodily-autonomy arguments. Thus, if abortion is not morally wrong, that is so because either (1) a fetus is not a person and does not have a right to life, which means that a fetus is a sort of being whose life is not wrong to end or (2) the pregnant woman has a right to her bodily autonomy, which means that, even if the fetus has a right to life or is a person, the fetus does not have a right to use another person’s body to sustain its life and, therefore, abortion is morally justified.

In “Just Better Utilitarianism,” Häyry posits his liberal utilitarianism in light of Jeremy Bentham’s words: “The question is not, Can they reason ? nor, Can they talk ? but, Can they suffer ?” 15 Häyry uses this reasoning on nonhuman animals. According to liberal utilitarianism, meat consumption, factory farming, and other related practices are immoral because animals can, indeed, suffer. 16 Their interest in not suffering is more basic than our need (or desire, to say it more accurately) to consume animal-based products, such as meat. Because it is wrong to satisfy less basic needs of one being by preventing the possibility of satisfying more basic needs of others, meat consumption and the other practices are morally wrong.

Now, if mindless humans such as fetuses can suffer (i.e., feel pain), could that undermine the notion that liberal utilitarianism justifies abortion? One might think so, because if abortion is permissible, then the more basic needs of the fetuses (avoiding suffering) would be ignored in favor of the less basic needs of pregnant women (controlling what happens to one’s body).

Studies often suggest that a cortex and intact thalamocortical tracts are necessary to experience pain. Since the cortex only becomes functional and the tracts only develop after 24 weeks, many studies hold that a fetus cannot experience pain until the final trimester. But in recent work, it has been argued that neuroscience cannot definitively rule out fetal pain before 24 weeks. 17 Although most abortions occur well before 24 weeks, some of the States in United States allow abortion even during the final trimester. 18

Suppose fetuses do feel pain. It seems that liberal utilitarians should at least be concerned about it. They could not simply ignore fetal pain.

In a landmark paper, Judith Jarvis Thomson argued that abortion is still morally permissible even on the assumption that fetuses have a right to life and are persons. To support her position, she offered the following hypothetical case.

Famous Violinist . You wake up and find yourself in a bed, attached to an unconscious famous violinist. He has been found to have a fatal kidney ailment, and the Society of Music Lovers has attached him to you because you alone have the right blood type to help. A doctor tells you: “We’re sorry you have been connected to this person. We would have never allowed it if we had known. But to unplug him now would kill him. Nevertheless, it’s only for nine months; after that, he will recover from his ailment and can safely be unplugged from you.” 19

Thomson’s reaction to the case was that although it would be very nice for you to remain attached, it is not your moral obligation. It is morally permissible for you to detach yourself from the violinist because, although he has a right to life, he does not have a right to use your body to sustain his own life. Because the case is, allegedly, analogous enough with pregnancy, the pregnant woman likewise has a right to detach the fetus from her, even in the cases where the fetus would die as a result. 20

To see what moral weight fetal pain, if it exists, would have, we can revise Thomson’s case so that detaching yourself from the violinist is very painful to him. Consider the following revised case.

Painful Detachment. You wake up and find yourself in a bed attached to an unconscious famous violinist. He has been found to have a fatal kidney ailment, and the Society of Music Lovers has attached him to you because you alone have the right blood type to help. A doctor tells you: “We’re sorry you have been connected to this person. We would never have allowed it if we had known. But to unplug him now would kill him very painfully. Nevertheless, it is only for nine months; after that, he will cover from his ailment and can safely be unplugged from you.”

Does the pain detaching yourself would cause make you morally obligated to remain attached to the violinist? Probably not. Does it give you a moral reason to consider whether you can do something to ease the pain? Probably yes. If it is possible, the violinist should be offered pain relief, if pain, as a liberal utilitarian must assume, has any moral relevance. Similarly, we should be concerned about fetal pain.

But now, what if we could ease the pain of animals in factory farming? If, given that fetuses do feel pain, we are only obligated to ensure that abortion does not cause the fetus to feel pain, not to prevent abortions per se, why we should stop killing animals? Is not enough that we make sure they are killed painlessly? If on the other hand, we believe that we should not kill animals for food even if we can do so without inflicting pain, why we should not abstain from killing fetuses as well?

A liberal utilitarian might have at least two replies. She might say that killing animals is unnecessary because the same goods can be achieved by other means, such as by eating plant-based food. However, there are no proper alternatives to abortion: the same goods that are achieved by abortion cannot be achieved by, for example, gestating the fetus to the term and giving it up for adoption. 21 One might also say that pregnancies happen inside women’s bodies while killing animals does not, and that this is morally relevant.

But now suppose we imagine that, thanks to new technology, it is no longer necessary to kill the fetus when ending the pregnancy prematurely. Perhaps sometimes, pregnancy does not happen inside a female body in the first place. 22 Consider the following cases.

Partial ectogenesis. It has become possible to detach a fetus from the female body in a very early phase of pregnancy and gestate the fetus inside an artificial womb instead. A woman gets pregnant and wants to have an abortion, but the doctor tells her: “You know, you don't need to kill the fetus. We can just remove it alive and gestate it in an artificial womb machine. Then, after a few months, you could give it up for adoption if you still feel you don’t want to have a child.”

Is the woman still entitled to have the fetus killed, or is she morally obligated not to kill the fetus? Surely, people’s intuitions differ here, but I suspect—and some studies suggest 23 —that at least many women would feel that avoiding the burdens of the pregnancy is not the point of abortion: the point of abortion is not to have a child at all. 24 , 25 , 26

To propose partial ectogenesis as an alternative to abortion would thus be to misunderstand the purpose of abortion. Since the purpose of the abortion is to have the fetus killed, but the justification for the abortion is bodily autonomy and integrity, when an artificial womb device becomes an option, another justification for abortion will be needed. That brings us to the next case.

Complete ectogenesis. It has become possible to create embryos in vitro and gestate them in artificial womb machines. A couple wants to have a child, but after the embryos are created and transferred into the machine, they change their mind. They do not want to have a child. However, the doctor tells them: “You know, you don’t need to destroy the embryo developing in the machine. You can just leave it there, and when the time comes, if you do not want the newborn, we can give it to some other couple that does want to have a child.”

Is the couple—either together or separately—still entitled to have the embryo destroyed, or are they morally obligated not to destroy it? 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 Again, our intuitions probably differ. But what seems to be relevant is whether the fetus itself is the sort of being whose life it is seriously morally wrong to end. So, it is likely that to determine what the couple or the woman should do, morally, in the above cases cannot be answered without answering the question of whether the fetus itself is entitled to a right to life. Häyry could just assume that embryos or fetuses are not the sort of beings (persons) whose life it is seriously morally wrong to end. But this simply assumes an answer to the very difficult question that, to my mind, should be answered first.

It is very easy to be a utilitarian when faced with simple scenarios. It is also easy to become a utilitarian in time of crisis: for instance, public health often uses a utilitarian approach to make triage decisions during pandemics 31 such as COVID-19. For an example of a simple case, consider the following.

A billionaire who is convinced by liberal utilitarianism donates one million dollars to the state on the condition that the money be spent to save as many of his fellow citizens’ lives as possible. The state has two choices: use the money for one ambulance helicopter that patrols a rural part of the country, or use the money for 10 ambulances that are used in major cities. The helicopter would save, on average, one life annually while the ambulances would save, on average, one hundred lives annually.

It is obvious what to choose. Other things being equal, the money should be spent for the ambulances, so that the greatest number of people would be saved.

But now suppose there is a third possibility. Use the money to fund a campaign to discourage women from choosing abortion. Suppose further that this money would save 1,000 embryos and fetuses from being aborted. Should the state choose this policy instead because it saves even more lives? It depends. It depends on whether we count fetuses and embryos as part of our moral community. If we do, then it seems to be a moral obligation to choose the campaign, but if we do not consider these mindless humans a part of our moral community, then there is no moral obligation to choose this option over the ambulances. 32

There are also recent real-life cases that illustrate the problem. For instance, there is an ongoing debate whether guidelines for treating extremely premature babies should be altered to free up ventilators for adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. 33 In some cases, a ventilator would give an adult a higher probability of survival than it would give the extremely premature baby who would otherwise get it. However, saving babies rather than adults would likely maximize life years saved, since a baby who survives is likely to live longer than an adult who does. It is difficult to apply any utilitarian approach successfully if we do not know what moral status to assign to the mindless human fetuses. 34

We could simply say that fetuses are not persons because they lack (self-)consciousness. But we could say many nonhuman animals lack that as well. Or someone could reply that being a person does not matter: what matters is that when killing a fetus (or embryo) we are depriving it of life unjustly. 35 Is not life itself a very basic need that outweighs any alleged needs or wants to control one’s body?