An official website of the United States government.

Here’s how you know

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

Occupational Safety and Health Administration

- 中文(简体) (Chinese-Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese-Traditional)

- Kreyòl ayisyen (Haitian Creole)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- Español (Spanish)

- Filipino/Tagalog

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Safety and Health Topics

Workplace Violence

- Workplace Violence Home

Risk Factors

Prevention programs.

- Training & Other Resources

Enforcement

- Workers' Rights

- Enforcement Procedures and Scheduling for Occupational Exposure to Workplace Violence . OSHA Directive CPL 02-01-058, (January 10, 2017).

- Guidelines for Preventing Workplace Violence for Healthcare and Social Service Workers ( EPUB | MOBI ). OSHA Publication 3148, (2016).

- Worker Safety in Hospitals: Caring for our Caregivers, Preventing Workplace Violence in Healthcare . OSHA.

- Taxi Drivers – How to Prevent Robbery and Violence . OSHA Publication 3976 (DHHS/NIOSH Publication No. 2020-100), (November 2019).

- Recommendations for Workplace Violence Prevention Programs in Late-Night Retail Establishments . OSHA Publication 3153, (2009).

This workplace violence website provides information on the extent of violence in the workplace, assessing the hazards in different settings and developing workplace violence prevention plans for individual worksites.

What is workplace violence?

Workplace violence is any act or threat of physical violence, harassment, intimidation, or other threatening disruptive behavior that occurs at the work site. It ranges from threats and verbal abuse to physical assaults and even homicide. It can affect and involve employees, clients, customers and visitors. Acts of violence and other injuries is currently the third-leading cause of fatal occupational injuries in the United States. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries (CFOI), of the 5,333 fatal workplace injuries that occurred in the United States in 2019, 761 were cases of intentional injury by another person. [ More... ] However it manifests itself, workplace violence is a major concern for employers and employees nationwide.

Who is at risk of workplace violence?

Many American workers report having been victims of workplace violence each year. Unfortunately, many more cases go unreported. Research has identified factors that may increase the risk of violence for some workers at certain worksites. Such factors include exchanging money with the public and working with volatile, unstable people. Working alone or in isolated areas may also contribute to the potential for violence. Providing services and care, and working where alcohol is served may also impact the likelihood of violence. Additionally, time of day and location of work, such as working late at night or in areas with high crime rates, are also risk factors that should be considered when addressing issues of workplace violence. Among those with higher-risk are workers who exchange money with the public, delivery drivers, healthcare professionals, public service workers, customer service agents, law enforcement personnel, and those who work alone or in small groups.

How can workplace violence hazards be reduced?

In most workplaces where risk factors can be identified, the risk of assault can be prevented or minimized if employers take appropriate precautions. One of the best protections employers can offer their workers is to establish a zero-tolerance policy toward workplace violence. This policy should cover all workers, patients, clients, visitors, contractors, and anyone else who may come in contact with company personnel.

By assessing their worksites, employers can identify methods for reducing the likelihood of incidents occurring. OSHA believes that a well-written and implemented workplace violence prevention program, combined with engineering controls, administrative controls and training can reduce the incidence of workplace violence in both the private sector and federal workplaces.

This can be a separate workplace violence prevention program or can be incorporated into a safety and health program, employee handbook, or manual of standard operating procedures. It is critical to ensure that all workers know the policy and understand that all claims of workplace violence will be investigated and remedied promptly. In addition, OSHA encourages employers to develop additional methods as necessary to protect employees in high risk industries.

Provides information on risk factors and scope of violence in the workplace to increase awareness of workplace violence.

Provides guidance for evaluating and controlling violence in the workplace.

Training and Other Resources

Provides online training and other resource information.

There are currently no specific OSHA standards for workplace violence. Also provides links to enforcement letters of interpretation.

Nursing Workplace Violence

- Increase in Nurse Violence

- Influence of COVID

- Long-Term Impacts

- How to Protect Nurses

Are you ready to earn your online nursing degree?

While workplace violence in healthcare has been a persistent problem for many years, the rates have spiked during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurses report escalating rates of COVID-related violence directed at them by frustrated and angry patients and their families.

A 2021 Workplace Health & Safety survey of registered nurses reports that 44% experienced physical violence at least once during the pandemic from patients, family members, or visitors. Over two thirds encountered verbal abuse at least once. RNs who provided direct care for patients with COVID-19 experienced more violence than nurses who did not care for these patients. Nurses also faced difficulty reporting these incidents to management.

The healthcare industry leads all other sectors for non-fatal workplace assaults. Within healthcare settings, violence in emergency departments has reached epidemic proportions during the pandemic. Emergency nurses are particularly vulnerable. Nearly 70 percent of emergency nurses report being hit or kicked at work.

Workplace violence injures healthcare professionals physically and psychologically, resulting in lost workdays, burnout, and turnover. The escalating rates of violence undermine efforts to provide quality patient care and hinder effective responses to combatting the COVID-19 virus.

Fast Facts About Workplace Violence Against Nurses

Sources: Nurses’ Experience With Type II Workplace Violence and Underreporting During the COVID-19 Pandemic | The COVID-19 Effect: World’s nurses facing mass trauma, an immediate danger to the profession and future of our health systems

The State of Workplace Violence Against Nurses

The rates of workplace violence have increased rapidly since the pandemic began. In August 2021 at a hospital in San Antonio , Texas, family members of COVID-19 patients physically and verbally abused healthcare workers for enforcing mask and visiting restrictions. Across the country, healthcare professions who advocate for vaccination and masking mandates have been subjected to online verbal abuse and threats of physical harm toward them or their family members.

Incidents of workplace violence are not restricted to the United States. A patient with COVID symptoms in Naples, Italy grew impatient waiting for treatment and spat at a doctor and nurse. His actions led to a shutdown of the entire ward and quarantine of all staff. In the United Kingdom, patients spat at and verbally abused staff who asked that they wear masks. In Mexico, healthcare workers accused of spreading the virus, have been assaulted and doused with bleach on public streets.

Nurses have become especially vulnerable to these kinds of physical and verbal assaults. Tina M. Baxter, an advanced practice registered nurse who provides consulting services for healthcare organizations, attorneys, and insurance professionals, has personally experienced workplace violence on several occasions.

— “Nurses are the most convenient target as we are with the patients the majority of the time. It is often the nurse who is tasked to enforce the rules about visitation, masking, and other mandates.”

–Tina Baxter, APRN, GNP-BC

She points out that “violence as a whole has increased during the pandemic and the lack of civil discourse in society, too often resorting to violence has become the first instinct instead of the last resort…Nurses are the most convenient target as we are with the patients the majority of the time. It is often the nurse who is tasked to enforce the rules about visitation, masking, and other mandates.”

A recent brief prepared by National Nurses United (NNU) support’s Baxter’s observations. NNU identifies multiple factors fueling COVID-related workplace violence. Nurses constantly face patients and families reacting with anger related to understaffing and increased wait times for care. They frequently deal with aggressive family members who refuse to adhere to visiting and masking requirements. The pandemic fatigue felt by many people and the misinformation spread by untrustworthy media and online outlets have also escalated the violent incidents.

The Influence of COVID on Rising Verbal and Physical Attacks

The recent Workplace Health & Safety survey connects COVID-related violence to the strained relations between nurses and patients. Over 67% of the nurses reported incidents of physical violence or verbal abuse between February and June 2020.

One in ten RNs indicated that reporting the violent incidents to management has become more difficult during the pandemic than before. Underreporting violence during the pandemic may be due to busy workloads, non-standardized reporting procedures, unclear definitions of what constitutes violence, and a perceived lack of management support.

Stressful conditions and more intense patient and family interactions are among the major forces behind the increased risks for aggression and violence toward nurses during the pandemic. Priscilla Grace Barnes, a registered nurse, personal trainer, and nutrition coach, explains that “part of being a nurse isn’t solely caring for the patient, it’s educating and communicating with the family. Many times this communication involves difficult situations around rules and regulations nurses have no control over. We are put in very tough situations.”

The pandemic may have helped spread the mistaken assumption that violence is part of the nursing profession . Many nurses believe that they have a responsibility to provide compassionate care even to those exhibiting violent behavior. As a result, nurses feel they must tolerate unsafe and dangerous conditions, rationalizing that the increase in violence stems directly from the anger and frustration experienced by patients and their families.

The Long-Term Impacts of Nurse Violence

A 2021 research study published in Healthcare reports that nurses who have experienced direct and indirect exposure to workplace violence are two to four times more likely to experience post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression, and burnout than nurses with no exposure.

According to the International Council of Nurses (ICN), rates of anxiety, trauma, and burnout have spiked dramatically since the onset of the pandemic. ICN data shows that the number of nurses reporting mental health distress has increased from 60% to 80% in many countries. Failure to address these mental health pressures will impact the already existing nursing shortage. ICN estimates a potential shortfall of 14 million nurses by 2030, which amounts to half the current nursing workforce.

— “Working in a hospital I often felt like I was pouring into a cup that had holes in the bottom of it – no matter how much I gave, the cup was never full.”

–Priscilla Barnes

Government, healthcare organizations, and nursing associations must address the pressing need for mental health support and preventive care for nurses. Barnes argues that healthcare facilities must promote psychological wellness to ensure nurse safety: “Nurses are caregivers. We live to serve. But caregivers have to be well. Working in a hospital I often felt like I was pouring into a cup that had holes in the bottom of it – no matter how much I gave, the cup was never full. This only leads to burnout of those who are the lifeline to the hospital – nurses.”

Despite the generally high regard for nurses held by the general public throughout the pandemic, negative public perceptions have also emerged about workplace safety and mental health challenges in the nursing profession. These unfavorable views may deter prospective nurses from entering the field at the time when they are most needed.

Preventing Workplace Violence Against Nurses: What Needs to Happen?

Even before the pandemic, healthcare workers experienced one of the highest rates of workplace violence compared to all other U.S. workers. According to a 2018 report by the Bureau of Labor Statistics , the number of violent injuries has steadily increased since 2011. Because the problem has reached epidemic proportions, nurses, medical facilities, and government agencies must work together to develop concrete measures to prevent the escalation of workplace violence.

— “Workplace violence should not and does not ‘come with the territory’ of being a nurse.”

–Rhonda Collins, DNP, RN, FAAN

One of the first issues to address is the culture of acceptance about violence in nursing. Rhonda Collins, the chief nursing officer at Vocera Communications, a healthcare technology company, cautions that “workplace violence should not and does not ‘come with the territory’ of being a nurse. Healthcare leaders must aggressively act to address this epidemic by validating concerns and ensuring nurses are heard and respected when reporting violent acts.”

What follows are some suggestions for proactive approaches to prevent workplace violence.

Nurses should also be aware of their surroundings, taking into account poorly-lit areas, placement of emergency exits, and crowded public spaces. Nurses can minimize risks by avoiding clothing or jewelry that can be grabbed or pulled. They should exhibit caution when dealing with patients and others who exhibit aggressive verbal cues (e.g., swearing or threatening language), and non-verbal behaviors (e.g., indications of drug or alcohol abuse or throwing objects.)

Nurses should become familiar with their employer’s health and safety policies, report any incidents, and support employees who have experienced violence. Nurses need to become involved in the development of safety policies, procedures, and emergency plans. All personnel should take advantage of available employer-sponsored programs or professional development opportunities on how to respond and prevent violence and how to use de-escalation techniques.

Collins and other nursing leaders argue that healthcare organizations must adopt a “zero-tolerance policy” on workplace violence. In addition to sponsoring educational and support programs, healthcare facilities must develop clear procedures for reporting violent incidents. To combat underreporting, employers must respond to violence seriously. Management has a responsibility to encourage staff to press charges against persons who commit assaults and to support employees when they report these incidents to law enforcement.

Healthcare facilities should upgrade and maintain security procedures and security systems, develop emergency response protocols, and hire sufficient security personnel. Collins suggests that employers provide nurses “with a wearable panic button that calls safety and security personnel so nurses don’t have to reach for a light on the wall when in distress.”

The Occupational Health and Safety Administration does not require employers to implement violence prevention programs, but it provides voluntary guidelines and may cite employers who fail to maintain a safe workplace environment. In early 2021, the House of Representatives passed the Workplace Violence Prevention Act for HealthCare and Social Workers, but it has not yet received Senate approval.

Although no federal laws currently protect healthcare worker safety, several states have passed legislation to protect them from workplace violence. These measures include the establishment of penalties for assaults on nurses, creating a disturbance inside a healthcare facility, or interfering with ambulance service. Only a small number of states require employer workplace prevention programs.

Nurse Resources for Preventing Workplace Violence

In response to the expanding awareness about workplace violence, several government agencies, professional nursing associations, and other special interest groups have developed resources to address safety concerns and violence prevention.

Workplace Violence Prevention Training for Nurses

This interactive course, developed by the National Institute for Occupational Health helps nurses identify risk factors for workplace violence and acquire skills to prevent and manage violent incidents. Nurses can earn continuing education credits by completing this course.

Reducing Workplace Violence with TeamSTEPPS

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality provides curriculum materials and webinars designed for clinical teams in a variety of healthcare settings. These TeamSTEPPS resources offer strategies to address difficult situations, reduce the risk of injury, and identify behavioral factors and emotional or psychological issues that lead to violence.

Hospitals Against Violence Workforce and Workplace Violence

Administered by the American Hospital Association, this website provides information on safety resources and practices including preparedness drills and de-escalation training. Featured resources include webinars on creating a culture of safety, mitigating risks, and violence prevention.

Violence, Incivility and Bullying

This website, maintained by the American Nurses Association provides downloadable educational materials, ANA position statements, and issue briefs on reporting incidents of workplace violence and bullying. It also provides links to several violence prevention resources and toolkits.

Workplace Violence Prevention – Interventions and Response Online Course

The Emergency Nurses Association offers several resources to help prevent, mitigate, and report workplace violence. This online course, free to ENA members, helps emergency nurses recognize, prevent, avoid, and respond to violent incidents caused by patients, visitors, intruders, other employees, and management.

Addressing Workplace Violence During COVID and Beyond

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the problem of escalating workplace violence in nursing. The healthcare industry and the nursing profession must embrace a cultural shift toward accountability and responsibility, providing a safe environment for all healthcare personnel, promoting positive patient care outcomes, and increasing the effectiveness of nursing practice.

Addressing the problem of workplace violence in nursing is in everyone’s interest. Nurses deserve to work in safe settings, performing their duties without fear of injury. Healthcare organizations will face greater nursing shortages due to injury or burnout, impacting the quality and cost of patient care. Effective workplace violence prevention initiatives must include transparent zero-tolerance policies, clear communication and procedures for incident reporting, and educational and support programs.

Meet Our Contributors

Priscilla Barnes

Priscilla Grace Barnes is a registered nurse who graduated with a bachelor of science in nursing and a bachelor of arts in Spanish from the University of Texas at Austin. With over 11 years experience, she has worked from the smallest of patients in the neonatal intensive care unit to the largest of life events with pediatrics and adults in the surgical setting. With a passion for helping others in and out of the hospital, Priscilla also founded Wellness in Bloom(WIB) where she is a personal trainer and nutritional coach. WIB promotes preventative medicine in a friendly environment, by replacing the stress that so often accompanies health and wellness goals with foundational habits that promote sustainability.

Tina Baxter, APRN, GNP-BC

Tina Baxter is an advanced practice registered nurse and a board-certified gerontological nurse practitioner through the American Nurses Credentialing Center. Baxter resides in Indiana and has been a registered nurse for over 20 years and a nurse practitioner for 14 years. She is the owner of Baxter Professional Services, LLC, a consulting firm which provides legal nurse consulting services for attorneys and insurance professionals, among other services. She is also the founder of The Nurse Shark Academy where she coaches nurses to launch their own businesses.

Rhonda Collins, DNP, RN, FAAN

Rhonda Collins, DNP, RN, FAAN has served as chief nursing officer since 2014. As CNO, Dr. Collins is responsible for working with nursing leadership groups globally to increase their understanding of Vocera solutions, share clinical best practices and to bring their specific requirements to Vocera’s product and solutions teams.

Dr. Collins holds a doctor of nursing practice from Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center and a master’s degree in nursing administration from the University of Texas. A registered nurse for 28 years, Dr. Collins is a frequent speaker on the evolving role of nurses, the importance of communication, and how to use technology to improve clinical workflows and care team collaboration.

Reviewed by:

Elizabeth M. Clarke, FNP, MSN, RN, MSSW

Elizabeth Clarke (Poon) is a board-certified family nurse practitioner who provides primary and urgent care to pediatric populations. She earned a BSN and MSN from the University of Miami.

Clarke is a paid member of our Healthcare Review Partner Network. Learn more about our review partners .

Whether you’re looking to get your pre-licensure degree or taking the next step in your career, the education you need could be more affordable than you think. Find the right nursing program for you.

You might be interested in

HESI vs. TEAS Exam: The Differences Explained

Nursing schools use entrance exams to make admissions decisions. Learn about the differences between the HESI vs. TEAS exams.

10 Nursing Schools That Don’t Require TEAS or HESI Exam

For Chiefs’ RB Clyde Edwards-Helaire, Nursing Runs in the Family

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Vivamus convallis sem tellus, vitae egestas felis vestibule ut.

Error message details.

Reuse Permissions

Request permission to republish or redistribute SHRM content and materials.

Understanding Workplace Violence Prevention and Response

Introduction.

The topic of workplace violence tends to dominate the news in the days following a major incident, but not every instance of workplace violence generates national headlines. Each year, an average of nearly 2 million U.S. workers report having been a victim of violence at work, according to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). And the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics puts the number of annual workplace homicides at about 400.

A 2022 SHRM survey of U.S. workers found that 28 percent of workers have either witnessed aggressive interactions between coworkers (20 percent) and/or have actually been involved in them personally (8 percent). While no prevention plan is an absolute protection against violence at work, understanding how to prepare for and react to violent conduct is imperative.

Introduction Compliance How to Prepare for Workplace Violence

- Identify the types of violence

- Create a violence prevention plan

- Consider insurance needs

- Know the warning signs

- Recognize risky situations

- Encourage reporting

How to Respond to Workplace Violence

- Active shooters

- Suicidal employees

- Domestic violence

- Bomb or arson threats

- Suspicious mail or packages

HR professionals find themselves in a unique position as both the leaders of workplace violence prevention and sometimes also the targets of employee rage. According to a 2019 SHRM research report, 19 percent of HR professionals are unsure or don't know what to do when they witness or are involved in a workplace violence incident and 55 percent don't know whether their organization has a workplace violence prevention program. See Survey: Half of HR Pros' Workplaces Experienced Violence and SHRM Workplace Violence Research Report .

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) defines workplace violence as the act or threat of violence, ranging from verbal abuse to physical assaults, directed toward people at work or on duty. Workplace violence also may include acts that result in damage to an organization's resources or capabilities. Many employers consider workplace harassment and bullying to be forms of workplace violence. Also included in this context is domestic violence that spills over into the workplace in the form of assaults, threats or other actions by outside parties with whom employees have relationships and that occur at the workplace.

What can employers do to protect their workers from becoming victims of workplace violence? The ultimate goal is to deter disgruntled insiders or nefarious outsiders from violence by making your company a hard target. A secondary goal is to make sure your company and workforce are prepared for violence so you can minimize casualties and respond quickly in the event of a violent incident. If you can save a life—or many—the return on investment will be well worth it.

See : Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries Summary Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Workplace Violence NIOSH Occupational Violence

The federal Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) Act includes a general duty clause requiring employers to "furnish to each of his employees employment and a place of employment which are free from recognized hazards that are causing or are likely to cause death or serious physical harm to his employees." According to OHSA's Enforcement Procedures and Scheduling for Occupational Exposure to Workplace Violence , "employers may be found in violation of the General Duty Clause if they fail to reduce or eliminate serious recognized hazards. Under this Instruction, inspectors should therefore gather evidence to demonstrate whether an employer recognized, either individually or through its industry, the existence of a potential workplace violence hazard affecting his or her employees. Furthermore, investigations should focus on whether feasible means of preventing or minimizing such hazards were available to employers." While there is currently no federal OSHA standard specific to workplace violence, there is potential for such a standard in the future, particularly for the health care industry.

Many states have OSHA-approved plans that must be "at least as effective" as the federal OSH Act and that often have further employee protections. Several states require employers to implement workplace violence prevention programs. For example, in 2017, California health care employers became regulated by the Workplace Violence Prevention in Health Care rule requiring a written workplace violence prevention plan, employee training, state reporting and more.

Common-law principles must also be considered in understanding employer liability for workplace violence, including the following:

- Premises liability is the duty of an employer to keep individuals on the premises safe from injury, including criminal and violent acts of others. Implementing security measures at worksites based on an assessment of potential violence specific to that site is recommended.

- Respondent superior refers to the vicarious liability of an employer for the acts of its employees acting within the course and scope of their employment. This liability is typically very fact-specific and often hinges on whether an employer's actions, or failure to act, contributed to the violent act.

- Negligence in hiring or retention of employees occurs when the employer knew or should have known the potential for violence. Conducting background screens upon hire as well as responding immediately and appropriately to threats of violence in the workplace can reduce this liability.

- Discrimination and harassment claims may arise when workplace violence is motivated by a protected characteristic such as race or religion.

How To Prepare for Workplace Violence

Preparing for any type of workplace violence is key. Larger companies with robust security departments have the advantages of resources and trained personnel who manage the security effort. But for smaller companies with little or no security measures in place, the responsibility often falls on the general counsel or the head of human resources. See How to Prepare Your Workforce for Violent Incidents .

As the FBI's Critical Incident Response Group points out in Workplace Violence: Issues in Response , there is no one-size-fits-all plan that employers can download and implement. Every employer will need a plan that is tailored to its particular circumstances and that considers company culture, physical layout, resources, management styles and other factors.

The New York State Department of Labor provides the following examples of employment situations that may pose higher risks of workplace violence:

- Duties that involve the exchange of money.

- Delivery of passengers, goods or services.

- Duties that involve mobile workplace assignments.

- Working with unstable or volatile people in health care, social service or criminal justice settings.

- Working alone or in small numbers.

- Working late at night or during early morning hours.

- Working in high-crime areas.

- Duties that involve guarding valuable property or possessions.

- Working in community-based settings.

- Working in a location with uncontrolled public access to the workplace.

Certain industries are also considered high-risk for workplace violence, including health care , taxi and for-hire drivers , and late-night retail establishments (gas stations, liquor or convenience stores, etc.).

Identify the Different Types of Workplace Violence

The California Division of Occupational Safety and Health, better known as Cal/OSHA, developed a model typology for workplace violence based on the perpetrator's relationship to the victim and/or place of employment that can be used by employers when assessing potential violence in the workplace. When conducting a worksite analysis or threat assessment, each type of perpetrator should be evaluated to determine the likelihood of a violent event and to identify mitigating measures that can be taken to address the particular risk.

Source: Cal/OSHA.

Create a Workplace Violence Prevention Plan

According to OSHA, the building blocks for developing an effective workplace violence prevention program include:

Management commitment and employee participation. Management commitment, including the endorsement and involvement of top management, will provide the motivation and resources necessary for a successful initiative. Including all levels of employees in the process and soliciting employee feedback allows workers to share their broad range of experience and skills and to provide different perspectives and viewpoints to identify workplace violence hazards and mitigate risks.

- Worksite analysis. Conducting a needs assessment to evaluate an organization's vulnerability to violence is a vital step in preparing a workplace violence prevention plan. This involves an inspection of the workplace to find existing or potential hazards that may lead to incidents of workplace violence, including an analysis of the physical environment and hazards specific to particular jobs, departments, shifts, etc. See Example Evaluation of the Physical Environment and Preventing Workplace Violence: 10 Critical Components of a Security lan .

- Substitution of the hazardous practice with a safer work practice such as the use of "buddy systems" when personal safety may be in jeopardy.

- Physical changes that either remove the hazard or create a barrier between the worker and the hazard, such as doors and locks, metal detectors, panic buttons, improved lighting, and accessible exits.

- Changes in work practices and administrative procedures such as a visitor sign-in process or a requirement for home health care workers to contact the office after each in-home visit.

- Safety and health training. Training should be provided at all levels of the organization upon hire and at least annually thereafter. Suggested topics include an overview of the workplace violence prevention plan, including identified hazards and control measures; risk factors for particular occupations; ways to prevent or diffuse volatile situations; the location and use of safety devices such as alarm systems and panic buttons; and other topics identified by the employer as appropriate to the particular workplace. NIOSH offers a video that discusses practical measures for identifying risk factors for violence at work and strategic actions that can be taken to keep employees safe. According to NIOSH, the guidance is based on extensive research, supplemented with information from other authoritative sources.

- Record-keeping and program evaluation. Maintenance of records is required, including required logs of work-related injuries and illnesses (OSHA Form 300), workers' compensation records, training records, safety committee minutes, and the identification and correction of recognized hazards.

Consider Insurance Needs

Employers should consult with their general liability and workers' compensation insurance providers to ensure adequate coverage. Workplace violence or active shooter insurance policies are available to supplement general liability coverage. According to the International Risk Management Institute, workplace violence insurance provides "coverage for the expenses that a company incurs resulting from workplace violence incidents. The policies cover items such as the cost of hiring independent security consultants, public relations experts, death benefits to survivors, and business interruption (BI) expenses."

Know the Warning Signs

Experts with the Center for Personal Protection & Safety say that when survivors of workplace shootings committed by co-workers remember the incident, they often recall signs that something was wrong—that there were behaviors that should have caused concern. Generally, any behavior that makes employees uncomfortable or leaves them feeling intimidated is cause for alarm.

These behaviors include being disruptive, aggressive and hostile as well as exhibiting prolonged anger, holding grudges, being hypersensitive to criticism, blaming others, being preoccupied with violence and being sad for a long period of time. Experts say what begins as sadness can lead to depression and suicide. Individuals who are contemplating suicide might think about taking their lives and the lives of others as well.

There are other signs. If someone who usually is friendly and outgoing becomes quiet and disengaged, that could be cause for concern. Sometimes people who experience a loss, a death, a reprimand, financial trouble, a layoff or termination can snap. Be mindful, too, of people who are the victims of stalking or domestic violence. Their personal lives might put their colleagues at risk. See Preventing Workplace Violence Inspired by COVID-19 .

Recognize Risky Situations

There are circumstances in every workplace that increase the risk of a violent incident, including terminating volatile employees and dealing with workers who show signs of potential violence due to a mental illness.

Terminations

According to psychologist Marc McElhaney, CEO of Critical Response Associates, a consulting firm that helps organizations conduct threat assessments, manage crises and separate high-risk workers from the organization safely, there are four general types of problem employees who might cause trouble if they are fired. However, it is important to note that there's no profile of someone most likely to commit violence—anyone is capable of it.

- The Workplace Bully has a history of intimidation. He gets away with bad behavior because no one wants to confront him or make him mad.

- The Disgruntled Employee believes she has been treated unfairly and can't let go of feeling abused by the organization. She is withdrawn, goes to work in a daze, is unhappy and blames the system for her problems. When she is fired, she might take that opportunity to get back at the company.

- The Overly Attached Employee is "the one who won't go away." This person's identity is dependent on his job. He doesn't have many friends or family. Work is his social life, his recreation, his sense of self. If he is fired, he'll feel betrayed, rejected and angry.

- The Nothing-Left-to-Lose Employee is usually in emotional distress because of recent, critical losses in her life. She might be divorced or widowed, have a limited support system, or even seem suicidal.

Mental Illness

There are times when an employee who is suspected or known by an employer to have a mental illness may seem on the verge of violent conduct. When can, or should, an employer act?

Legally, the federal Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and many state laws prohibit discrimination against employees based on an actual or perceived disability, and mental illness is included within the definition of disability. An employer may wish to require a fitness-for-duty exam for a potentially mentally ill employee, but targeting an employee simply due to a real or perceived disability would run afoul of the law, as the ADA generally does not allow medical exams during employment.

However, if such an employee is displaying some of the indicators of potential violence in the checklist above, and the employer has good reason to believe that an employee has a condition that may present a threat of harm to himself or others, requiring an exam would be allowable. The reason must be based on objective facts, not fear or conjecture. The ADA also allows employers to take action if they can show that an employee poses a direct threat to others, defined as "a significant risk to the health or safety of others that cannot be eliminated by a reasonable accommodation." The threat must be based on "an individualized assessment of the [employee's] present ability to safely perform the essential functions of the job" based on a reasonable medical judgment or objective evidence. According to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, this assessment must include the following factors:

- The duration of the risk.

- The nature and severity of the potential harm.

- The likelihood the potential harm will occur.

- The imminence of the potential harm.

The availability of any reasonable accommodation that would reduce or eliminate the risk of harm must also be considered.

Employers are encouraged to seek legal counsel prior to taking action or requiring medical exams of employees to avoid violating the ADA.

See Managing High-Risk Employees and Creating a Mental Health-Friendly Workplace .

Encourage Reporting

Employee reports of suspicious or threatening behavior are critical to effective violence prevention programs, and employers should ensure that the internal culture supports such reporting. Workers need to have confidence that their reports will be taken seriously, that their identities won't be divulged unnecessarily and that leaders will take appropriate action. If employees lack confidence in their manager to handle a threatening situation or to report such incidents, employers may want to appoint a more senior person or an HR representative to field concerns.

Furthermore, employers might want to set up a hotline where employees can anonymously report concerns. Whatever method they choose, businesses must make sure employees understand that they must respond immediately and diligently if they perceive a threat. It is a good idea during training to review scenarios that employees might want to report and to explain that they should err on the side of over-reporting.

How to Respond to Workplace Violence

Despite diligent efforts to prevent workplace violence, incidents can and do occur. There is no fail-safe method to eliminate workplace violence entirely, although implementing the prevention strategies recommended by experts and discussed in this toolkit can be very effective. When violence does enter the workplace, employers can be prepared by identifying early the existence of the threat, responding appropriately by involving law enforcement and other professionals, and ensuring that all employees are knowledgeable about effective strategies to reduce the likelihood of injury.

Assess Threats

A threat assessment team is an internal committee of employees from different levels and expertise within an organization whose role is to assess the seriousness and likelihood of a threat once it has been recognized. Training for the threat assessment team should include, at a minimum:

- Behavioral and psychological aspects of workplace violence.

- Identification of concerning behaviors.

- Violence risk screening.

- Investigatory and intervention techniques.

- Incident resolution.

- Multidisciplinary case management strategies.

Most employers will need to engage external specialists with expertise in risk management and workplace violence prevention and intervention to provide the necessary training.

The primary goal of a threat assessment team is to receive and review nonemergency incident reports and recommend appropriate action. In the event of imminent emergency situations, emergency personnel should be contacted immediately.

The threat assessment team can accomplish four goals when it conducts its interview of an employee who has threatened others or acted inappropriately:

- Alert the employee that his behavior has been noticed.

- Give him the opportunity to tell his story.

- Gather information about the person.

- Let him know the behavior is unacceptable.

When internal expertise is not available for certain threats, employers will need to consult with an external professional experienced in threat assessments and crisis management.

Active Shooters

In the event of an active shooter in the workplace, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) provides guidance employers can use to ensure that their employees know how to respond and understand when to run, hide or fight .

See Active Shooter – How to Respond .

Suicidal Employees

Suicide threats should always be taken seriously. A human resource professional or the employee's supervisor may be the first person to identify a potentially suicidal employee, so it is critical to recognize the warning signs and encourage at-risk employees to seek help.

If an employee appears to be planning to take action immediately, local emergency authorities should be contacted, since employers usually are not qualified to handle such a situation directly. If there are doubts as to whether the threat is immediate, the HR professional should contact local services, such as an employee assistance program, suicide hotline or hospital. Given the risks of failing to act, it is best to seek professional assistance as soon as possible.

The following are some of the signs you might notice in an employee that may be reason for concern:

- Talking about wanting to die or wanting to kill oneself.

- Making a plan or looking for a way to kill oneself, such as searching online.

- Buying a gun or stockpiling pills.

- Feeling empty, hopeless or like there is no reason to live.

- Feeling trapped or in unbearable pain.

- Talking about being a burden to others.

- Increasing the use of alcohol or drugs.

- Acting anxious or agitated; behaving recklessly.

- Sleeping too little or too much.

- Withdrawing from family or friends or feeling isolated.

- Showing rage or talking about seeking revenge.

- Displaying extreme mood swings.

- Saying goodbye to loved ones; putting affairs in order.

Source: The National Institute of Mental Health.

See NIMH Frequently Asked Questions About Suicide .

Domestic Violence

Domestic violence becomes a workplace issue when the violence follows a victim to work. Employers should avoid dismissing domestic violence as a personal issue as many victims of domestic violence can benefit from the support of their employer. By developing individual and workplace safety plans, employers can prepare for the potential that a domestic situation will escalate in the workplace. According to the Canadian Centre for Occupational and Health Safety, such plans may include the following actions:

- Ask if the victim has already established protection or restraining orders. Help to make sure all the conditions of that order are followed.

- Talk to the employee; work together to identify solutions. Follow up and check on his or her well-being.

- Ask for a recent photo or description of the abuser. Alert others such as security and reception so they are aware of who to look for.

- When necessary, relocate the worker so that he or she cannot be seen through windows or from the outside.

- Do not include the employee's contact information in publicly available company directories or on the company website.

- Change the employee's phone number, have another person screen his or her calls, or block the abuser's calls and e-mails.

- Preprogram 911 on a phone or cellphone. Install a panic button in the employee's work area or provide personal alarms.

- Provide a well-lit parking spot near the building or escort the individual to his or her car or to public transit.

- Offer flexible work scheduling if it can be a solution.

- Call the police if the abuser exhibits criminal activity such as stalking or unauthorized electronic monitoring.

- If the victim and abuser work at the same workplace, do not schedule both employees to work at the same time or location wherever possible.

- If the victim and abuser work at the same workplace, use disciplinary procedures to hold the abuser accountable for unacceptable behavior in the workplace.

[Adapted from: Making It Our Business (2014) from the Centre for Research & Education on Violence against Women & Children]

An Employer's Role in Preventing Partner Abuse

When Domestic Violence Comes to Work

What Employers Can Do When Domestic Violence Enters the Workplace .

Bomb or Arson Threats

Employers should take all bomb or arson threats seriously. The Department of Homeland Security provides a Bomb Threat Checklist employers can use to ensure that all employees know how to handle bomb threats and the procedures to follow.

For threats made via phone, the DHS provides the following guidance:

- Keep the caller on the line as long as possible. Be polite and show interest to keep them talking.

- DO NOT HANG UP, even if the caller does.

- If possible, signal or pass a note to other staff to listen and help notify authorities.

- Write down as much information as possible—caller ID number, exact wording of threat, type of voice or behavior, etc.—that will aid investigators.

- Record the call, if possible.

Suspicious Mail or Packages

All employees with mail-handling responsibilities should be trained in identifying suspicious packages and mail. See USPS: Handling and Processing Mail Safely .

If a suspicious package or piece of mail is identified, employees should know who to contact internally and when emergency personnel should be contacted. In addition, employees should follow identified procedures, including the following:

- Remain calm.

- Do not open the letter or package.

- Leave the item where it is or place it gently on a flat surface.

- Cover the item using a trash can, article of clothing, etc.

- Shut off fans or equipment in the area that circulate air.

- Alert others to leave the area and keep away from the item.

- Evacuate the area, closing the door and blocking the bottom of the door with a towel, coat, etc.

- Wash hands with soap and water.

Employers may want to post these procedures within the mailroom or provide mail-handling employees with pocket cards or another means to readily access the information.

Related Resources

Preventing Workplace Violence: A Road Map for Healthcare Facilities

Workplace Violence Policy

Workplace Violence Prevention Policy

Weapon-Free Workplace Policy

Available in the SHRM Store:

Give Your Company a Fighting Chance: An HR Guide to Understanding and Preventing Workplace Violence

Workplace Violence: The Early Warning Signs

Example Workplace Violence Prevention Programs and Procedures:

Washington State

State of California

External Resources

There are numerous resources available to employers to assist in preparing a workplace violence prevention program. Federal and state OSHA offices are a good place to start. In addition, NIOSH, the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) , and other state and federal offices may offer tools and resources to assist employers.

DOL Workplace Violence Program OSHA Workplace Violence Prevention Programs FBI: Workplace Violence: Issues in Response Workplace Violence Prevention Strategies and Research Needs Example Workplace Violence Handbook Online Workplace Violence Prevention Course for Nurses NIOSH Health Hazard Evaluations DHS Interagency Security Committee Violence in the Federal Workplace Guide

Related Content

Rising Demand for Workforce AI Skills Leads to Calls for Upskilling

As artificial intelligence technology continues to develop, the demand for workers with the ability to work alongside and manage AI systems will increase. This means that workers who are not able to adapt and learn these new skills will be left behind in the job market.

Employers Want New Grads with AI Experience, Knowledge

A vast majority of U.S. professionals say students entering the workforce should have experience using AI and be prepared to use it in the workplace, and they expect higher education to play a critical role in that preparation.

Advertisement

Artificial Intelligence in the Workplace

An organization run by AI is not a futuristic concept. Such technology is already a part of many workplaces and will continue to shape the labor market and HR. Here's how employers and employees can successfully manage generative AI and other AI-powered systems.

HR Daily Newsletter

New, trends and analysis, as well as breaking news alerts, to help HR professionals do their jobs better each business day.

Success title

Success caption

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Ann Med Surg (Lond)

- v.78; 2022 Jun

Workplace violence in healthcare settings: The risk factors, implications and collaborative preventive measures

Mei ching lim.

a Department of Public Health Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Jalan UMS, Kota Kinabalu, 88400, Sabah, Malaysia

Mohammad Saffree Jeffree

Saihpudin sahipudin saupin, nelbon giloi, khamisah awang lukman.

b Centre for Occupational Safety & Health, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, Malaysia

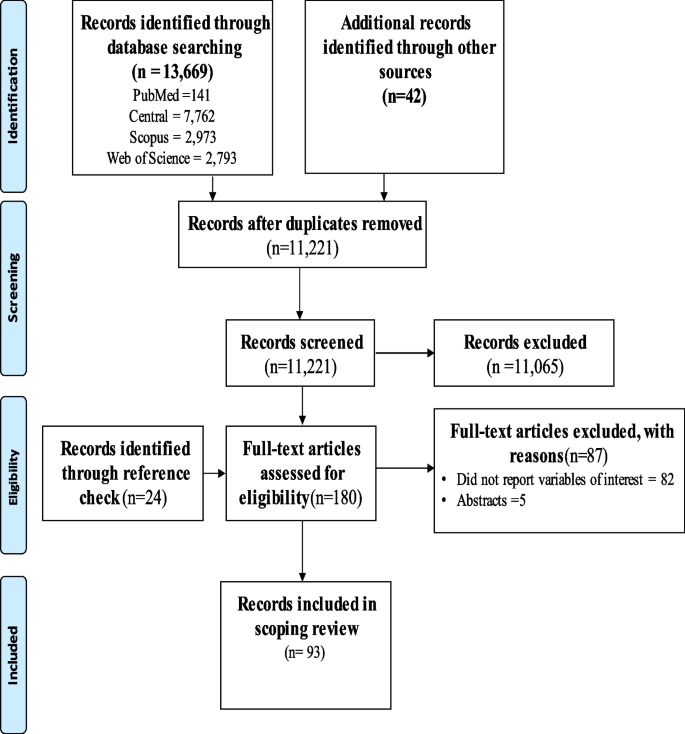

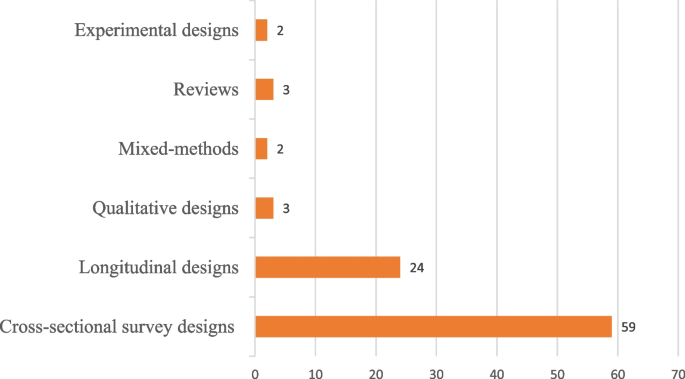

Violence at work refers to acts or threats of violence directed against employees, either inside or outside the workplace, from verbal abuse, bullying, harassment, and physical assaults to homicide. Even though workplace violence has become a worrying trend worldwide, the true magnitude of the problem is uncertain, owing to limited surveillance and lack of awareness of the issue. As a result, if workplace violence, particularly in healthcare settings, is not adequately addressed, it will become a global phenomenon, undermining the peace and stability among the active communities while also posing a risk to the population's health and well-being. Hence, this review intends to identify the risk factors and the implications of workplace violence in healthcare settings and highlight the collaborative efforts needed in sustaining control and prevention measures against workplace violence.

- • Workplace violence needs to be addressed more comprehensively, involving shared responsibilities from all levels.

- • Emphasis on healthcare management's commitment, assurance, and clearly defined policy, reporting procedures, and training.

- • The healthcare workers' commitment to update their awareness and knowledge regarding workplace violence.

- • The provision of technical support and assistance from professional organizations, NGOs, and the community.

1. Introduction

Violence affects people at all levels of society and can occur anywhere; at home, on the streets, in schools, workplaces, and institutions. Violence had previously been overlooked as a Public Health issue due to the lack of a clear definition, undeniably a complex and diffused matter. It is not as simple as relating violence to scientific facts to define it; instead, it is a matter of judgment of appropriate and acceptable behaviors influenced by culture, values, and social norms. Violence is determined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the deliberate use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, that has consequences or has a high probability of resulting in injury, death, mental distress, mal-development, or deprivation.

Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) defines workplace violence as any act or threat of physical violence, harassment, intimidation, or other threatening disruptive behavior that occurs at work [ 1 ]. While physical violence (which includes beating, biting, kicking, pushing, slapping, stabbing, and shooting) in the workplace has been acknowledged, little has been done to address the presence of psychological violence until recent years [ 2 ]. Psychological violence is the intended use of power, including the threat of physical force against another person or group with the potential to impair the affected individual's physical, mental, spiritual, moral, or social development [ 2 ]. Besides, harassment which is also categorized as a type of violence, is defined as any behavior that degrades, humiliates, irritates, alarms, or verbally insults another person, including abusive words, bullying, gestures, and intimidations [ 3 ]. This review aims to determine the risk factors and consequences of workplace violence in healthcare settings, as well as emphasizing the joint efforts required to enhance the control and preventative measures of workplace violence.

2. Workplace violence in healthcare settings

Although violence in the workplace affects almost all sectors and groups of workers, it is apparent that violence in healthcare settings provides a significant risk to public health and an occupational health issue of growing concern. The healthcare and social service industries have the greatest rates of workplace violence injuries, with workers in these industries being five times more likely to be injured than other workers [ 4 ]. In addition, workplace violence in the health sector is estimated to account for about a quarter of all workplace violence [ 5 ]. Workplace violence is constantly on the rise in the health industry due to rising workloads, demanding work pressures, excessive work stress, deteriorating interpersonal relationships, social uncertainty, and economic restraints [ 5 ].

Healthcare workers accounted for 73% of all nonfatal workplace injuries and illnesses due to violence in 2018 [ 4 ]. According to World Health Organization (WHO), it is estimated that between 8% and 38% of health workers suffer physical violence at a certain point in their careers. At the same time, many more are exposed or threatened with verbal aggression [ 6 ]. Most violent cases are committed by patients’ family members or friends and followed by patients themselves [ 4 , 7 ]. Violence in healthcare settings worsens when there is a crisis, emergency, or disaster which involves large groups of people who are even more overwhelmed with panic attacks, shock, uncertainties, fears, and worries of the conditions they or their family members are going through [ 6 ]. As a result, healthcare workers become the targets to vent their anger or frustrations. The most vulnerable healthcare workers victimized are staff at emergency departments, especially nurses and paramedics, and staff directly involved with in-patient care [ 5 , 6 ].

Furthermore, the Healthcare Crime Survey conducted by International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety Foundation's (IAHSSF) in 2019 reported the assault rates against healthcare workers increased from 9.3 incidents in 2016 to 11.7 per 100 beds in 2018, which is the highest rate that IAHSSF has ever recorded since 2012 [ 8 ]. 85% of workplace violence occurrences were classified as National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Type II Customer/Client Workplace Violence, which involves violence directed at employees by customers, clients, patients, students, inmates, or anybody else for whom an organization provides services [ 9 ]. According to a meta-analysis of 47 observational studies, the overall prevalence of workplace violence against healthcare professionals was 62.4%, with verbal abuse accounting for the highest majority (61.2%), followed by psychological violence (50.8%), threats (39.5%), physical violence (13.7%), and sexual harassment (6.3%) [ 10 ].

Even though some institutions may have a proper formal incident reporting system, there are still many incidents, especially in the forms of bullying, verbal abuse, and harassment, unreported [ 11 ]. Lack of reporting guidelines or policy, lack of trust in the reporting system, and fear of retaliation are among the many reasons for underreporting [ 12 , 13 ]. For example, in Malaysia, with the launching of the guidelines and training modules to address and prevent violence against healthcare workers, more cases were reported with a drastic 159% increase from 167 cases in December 2017 to 432 cases in December 2018 [ 14 ]. The Emergency Department and the Psychiatry and Mental Health Departments were high-risk areas, as they were in other countries, with the most common perpetrators being patients, their relatives, or visitors [ 14 ]. While verbal violence, physical assault, intimidation, and sexual harassment were among the types of workplace violence documented [ 14 ], cyberbullying has been on the rise in recent years, with humiliation, defamation, and unlawful video recording in healthcare settings.

3. Risk factors of workplace violence in healthcare settings

The etiology of workplace violence can be pretty complex, and many risk factors are related to both the perpetrators and the healthcare workers assaulted. The environments under which care and services are provided in healthcare settings contributed to healthcare workers being more prone to occupational violence. Many studies were conducted, and some of the risk or associating factors that contributed to the amplified incidence of violence towards healthcare workers over the recent years are: (i) attitudes and behaviors of patients, family members, friends, or visitors who are often under intense emotional charge and expectations [ [15] , [16] , [17] ]; (ii) healthcare workers and work factors which include shortage of staffs, inexperienced or anxious staffs, poor coping mechanism and lack of training [ [18] , [19] , [20] , [21] , [22] ]; and (iii) system or environmental factors (overcrowded areas, long waiting hours, inflexible visiting hours, lack of information as well as difference of language and culture) [ 15 , 17 , 19 , 20 , 23 , 24 ].

4. Effect of workplace violence in healthcare settings

Violence against healthcare workers in any situation is inexcusable, especially when they are working around the clock to ensure that everyone receives the best treatment possible. The effect of violence harms healthcare employees' physical and psychological well-being of healthcare workers [ 6 ]. Victims of violence are more likely to experience demoralization, depression, loss of self-esteem, ineptitude as well as signs of post-traumatic stress disorders like sleeping disorders, irritability, difficulty concentrating, reliving of trauma, and feeling emotionally upset [ 7 , 17 , 24 , 25 ].

Furthermore, the negative implications of such widespread violence in healthcare sectors have a significant impact on the delivery of health care services, including a decline in the quality of care delivered, increased absenteeism, and health workers' decision to leave the field [ 5 , 15 , 17 , 19 , 25 ]. As a result, the number of health services available to the general public will be limited, resulting in increased healthcare costs due to resource constraints. In addition, if healthcare workers leave their employment due to harassment and threats of violence, equal access to primary health care would be threatened, particularly in developing countries where the number of healthcare workers is insufficient to meet the needs and demands of the population.

Many healthcare employees mistakenly feel that workplace violence is just part and parcel of their jobs [ 26 , 27 ] and that they were unlucky enough to be in the wrong location at the wrong time. Many employees believe no action will be taken against the perpetrators [ 28 ], or they refuse to endure the stigmatization and the inconvenience of filing reports and following through on legal proceedings [ 29 , 30 ]. They are typically concerned that if they speak up about what has occurred to them, they will be shamed or labeled incompetent with a lack of supervisory support [ 12 , 29 ]. Furthermore, the harassed healthcare workers are even more concerned that the offenders may inflict additional harassment, violence, or threats on them and their family members if reports are made [ 31 ].

Hence, it further implies the need for proper awareness and recognition followed by clearly defined control and prevention measures of workplace violence in healthcare settings to prevent the negative impact of workplace violence to both the healthcare staffs and services. These measures are also vital to ensure that all healthcare workers, especially the front liners, are well protected in a safe working environment so that health care services can be continued to run smoothly without any interruptions for the benefit of the community.

5. Collaborative efforts in prevention and management of workplace violence in healthcare settings

The detrimental effects, mainly the psychological impact of workplace violence on affected healthcare employees, are one of the most critical reasons it must be handled before it escalates to higher absenteeism rates or further affects healthcare workers' overall performance. It will have even more negative implications for the healthcare sector when staffing is already scarce, and patient loads continue to rise inexorably.

Nonetheless, there is still much room for improvement in workplace violence awareness and abilities. There is an essential need to have a strong collaborative effort, support, and commitment from top management and the workers to protect themselves. There is no single guideline that is suitable for all settings. Hence, the management of each healthcare setting needs to create or adapt and establish a practical, acceptable and sustainable workplace violence prevention program. It should be according to the needs of their respective environments, using the available guidelines or recommendations by WHO, ILO, DOSH, and evidence-based research.

In non-emergency settings, interventions to prevent violence against healthcare professionals focus on techniques to better manage aggressive patients and high-risk visitors while in emergency circumstances, interventions are more focused on assuring the physical security of healthcare facilities [ 6 ]. Among some of the prevention and control measures in the sequence of effectiveness include; (i) substitution by transferring a client or patient with a history of violent behaviour to a more suitable secure facility or area [ 13 ]; (ii) engineering control measures which include installing barrier protection, metal detectors and security alarm systems, allocating conducive patients or visitors areas and clear exit routes [ 1 , 13 ]; (iii) administrative and work place practise controls which include implementing workplace violence response and zero-tolerance policies [ 1 , 17 , 24 , 32 ], ability to resolve conflict situation [ 33 ], establishing mandatory timely reporting system [ 34 ], ensuring employees are not working alone [ 35 ], flowchart for assessing and response in emergency situations [ 1 , 35 ]; (iv) post-incident procedures and services that include trauma-crisis counselling, critical-incident stress debriefing and employee assistance programs [ 35 ]; (v) safety and health training in order to ensure that all staff members are aware of potential hazards and how to protect themselves and their co-workers through established policies and procedures [ 32 , 35 , 36 ].

Aside from that, international or regional professional organizations, councils, and associations play essential roles in supporting, participating in, as well as contributing to initiatives and mechanisms aimed at minimizing and eliminating the potential risks of workplace violence in healthcare settings [ 5 , [37] , [38] , [39] ]. It includes but is not limited to (i) actively advocating on the awareness and training for workplace violence; (ii) incorporating in their codes of practice, codes of ethics, and clauses concerning the unacceptance of any form of workplace violence; (iii) integrating accreditation procedures in healthcare institutions on the requirement of measures aimed at preventing workplace violence; (iv) establishing workplace violence surveillance by mandatory and guided data collection procedures on the incidents of violence in all healthcare settings; and (v) offering support for victims of workplace violence, specifically in the form of legal aid if necessary.

In addition, participation and contribution from community groups, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), as well as business corporations in terms of technical support and financial assistance, play an essential part in curbing and preventing workplace violence in the healthcare settings [ 5 , 35 , [37] , [38] , [39] ]. Among the initiatives and activities which are highlighted include (i) creating and maintaining a strong network of information and expertise in workplace violence; (ii) assisting in promoting awareness of the risks of workplace violence; (iii) participating in training and educational programs; (iv) assisting in the support structure for the prevention and management of workplace violence; as well as (v) incorporating and emphasizing the importance of good communication skills and coping mechanism among the healthcare workers.

Summary of the risk factors, effects as well as the collaborative efforts which are important in the control and prevention measures for workplace violence in healthcare settings are tabulated in Table 1 .

Summary of risk factors, effects and collaborative management of workplace violence in healthcare settings.

6. Conclusion

It is undeniable that workplace violence needs to be addressed more comprehensively, involving shared responsibilities from all levels. These include (i) government's legislations; (ii) healthcare management's dedication, firm support, assurance, and clearly defined policy, reporting procedures, and training; (iii) the healthcare workers' commitment to update their awareness and knowledge regarding workplace violence; and (iv) the provision of technical support and assistance from professional organizations, NGOs, and the community.

Sources of funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

No ethical approval is required for this review.

Not applicable as it is a review and does not involve any new data collection from healthcare workers.

Author contribution

Mei Ching Lim drafted the initial manuscript and was involved in the literature search. Mohammad Saffree Jeffree was responsible for conceptualizing the study, facilitating manuscript writing, and approving the final manuscript. Saihpudin @ Sahipudin Saupin, Nelbon Giloi, and Khamisah Awang Lukman contributed expert input in literature search and facilitated manuscript writing. All authors have seen and approved the final manuscript.

Registration of research studies

Not applicable as it is a review and does not involve any new data collection from healthcare workers .

Dr Mei Ching Lim.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors report no conflict of interest nor proprietary or commercial interest in any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article.

Acknowledgements

Essay about Workplace Violence

What is workplace violence.

Workplace violence is violence or the threat of violence against workers. It can occur at or outside the workplace and can range from threats and verbal abuse to physical assaults and homicide, one of the leading causes of job-related deaths (Osha 2018). Bullying is now considered workplace violence because it has become more common and is also a factor that leads to physical violence. Workplace bullying includes acts of continual hostile conduct that deliberately hurt another person emotionally, verbally, or physically (Mondy 2016).

Bullying can be broken into two parts, the first is physical and the second is psychological. Physical bullying is intimidating or threatening actions like screaming or shoving. Another example would be the invasion of a person’s personal space. Psychological bullying is not as instant, yet a tactic that involves emotions and thinking. Some examples are ridiculing a person in a harmful manner or staring at someone with hostility. Bullying behaviors are now included in most companies’ workplace violence policy. Ultimately, workplace violence is a major issue for employers and employees. This paper will discuss the types of workplace violence, the causes, the impact, statistics, the warning signs and prevention methods for workplace violence.

Types of Workplace Violence

According to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (OSHA), there are five categories of workplace violence. The five types include; criminal intent, customer/client, worker-on-worker, personal relationships, and ideological. Criminal intent is when there is no relationship to the company or an employee. This type of violence occurs while another crime is being committed like shoplifting or robbery. Employees at gas stations and liquor stores, taxi drivers, police officers, and convenience store managers working night shifts face the greatest danger (Mondy 2016). Next is a customer/client affair that transpires while the victim is at their workplace. Social service workers and healthcare workers are the main targets for this mishap.

Following that is worker-on-worker violence. This attack is just what it sounds like, a current or former employee has decided to attack a current employee in the workplace. This could be considered the most common because there are plenty of reasons a person gets irritated or fed up with a coworker. Other reasons are a laid off employee or an employee that was hired without a thorough background check. The next type is personal relationships. This type goes hand in hand with domestic violence.

Typically, the perpetrator has no intentions or bad relationship with the company, they are only focused on the person they know. Women are victims of personal relationships way more than their counterparts. Lastly, ideology is focused on the assassins more than the victims. Ideology is rooted from religious or political views. The type of people associated with this are generally extremists or value driven groups. Examples would be an active shooter or terrorist attacks.

Causes of Workplace Violence

All five types of violence can occur at any time for any given reason. Now we will discuss some of the causes of workplace violence. An employee could be stressed or in denial and those are two causes. Human Resources plays a part in the other two causes which are a lack of pre-employment screening and a lack of an Employee Assistance Program (EAP). Stress is a natural occurrence in any workplace that all employees encounter. Stress could cause an employee to become angry, frustrated or hostile with others. Employers all try to enforce the, “leave your stress at the door” method, but we all know that is not the case. Personal stress could also lead to a workplace incident. Some employers refuse to accept the warnings and behaviors of stressed employees and this covers denial. By ignoring the signs of an employee, the company is putting their employees at risk. Acting as if there is no problem when a potential problem is occurring is equally as dangerous as the workplace violence taking place.

Human resources has two opportunities to lessen the causes by processing a full background check and enforcing the Assistance Programs the company offers. If Human Resources does not run a thorough background check, then there is the possibility that a person with a violent past or a person that is prone to violence might be hired. An EAP is a work-based intervention program designed to assist employees in resolving personal problems that may be adversely affecting the employee’s performance. An EAP could diffuse a situation before the employee has a chance to act.

The Impact of Workplace Violence

Workplace violence undoubtedly affects the person involved, but is also impacts coworkers, executives, clients and the community. Medical bills, workers’ compensation and legal fees are direct losses for a company. While a decrease in productivity, low-morale and negative image are all indirect losses. According to Lower & Associates, as many as half a million employees miss an estimated 1.8 million work days each year resulting in $55 million in lost wages (Ricci 2018). The impact of workplace violence is substantial and can also carry an immense cost to a company.

Every year 2 million American workers report having been victims of workplace violence. Of that 2 million, it is estimated that 25% of workplace violence goes unreported (National Safety Council 2018). According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 409 people were fatally injured in work-related attacks in 2014 (National Safety Council 2018). According to Injury Facts 2016, workplace violence is the third leading cause for deaths overall (National Safety Council 2018). The workers experiencing the most workplace violence are healthcare workers, employees in professional and business services like education, law and media. According to OSHA, taxi drivers are more than 20 times more likely to be murdered on the job than other workers (National Safety Council 2018). According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, women are overwhelmingly victims when it comes to workplace violence (Ricci 2018).

Warning Signs

Before workplace violence occurs, there are warning signs. Whether the signs are physical or psychological, verbal or non-verbal they still can be strong indicators to a potentially violent situation. An employee that is experiencing a high level of stress may display the following actions; crying, sulking or temper tantrums, excessive absenteeism or lateness, pushing the limit of acceptable conduct or disregarding the health and safety of others, disrespect for authority, swearing or emotional language, an inability to focus, talking about the same problems repeatedly without resolving them, or social isolation. These are some additional warning signs that lead to workplace violence; sweating, trembling or shaking, flushed or pale face, clenched jaws or fists, a change in voice, glaring or avoiding eye contact, or violating your personal space. These are all examples of signs that could be clues to a person’s future behavior, but they are also signs that could be prevented.