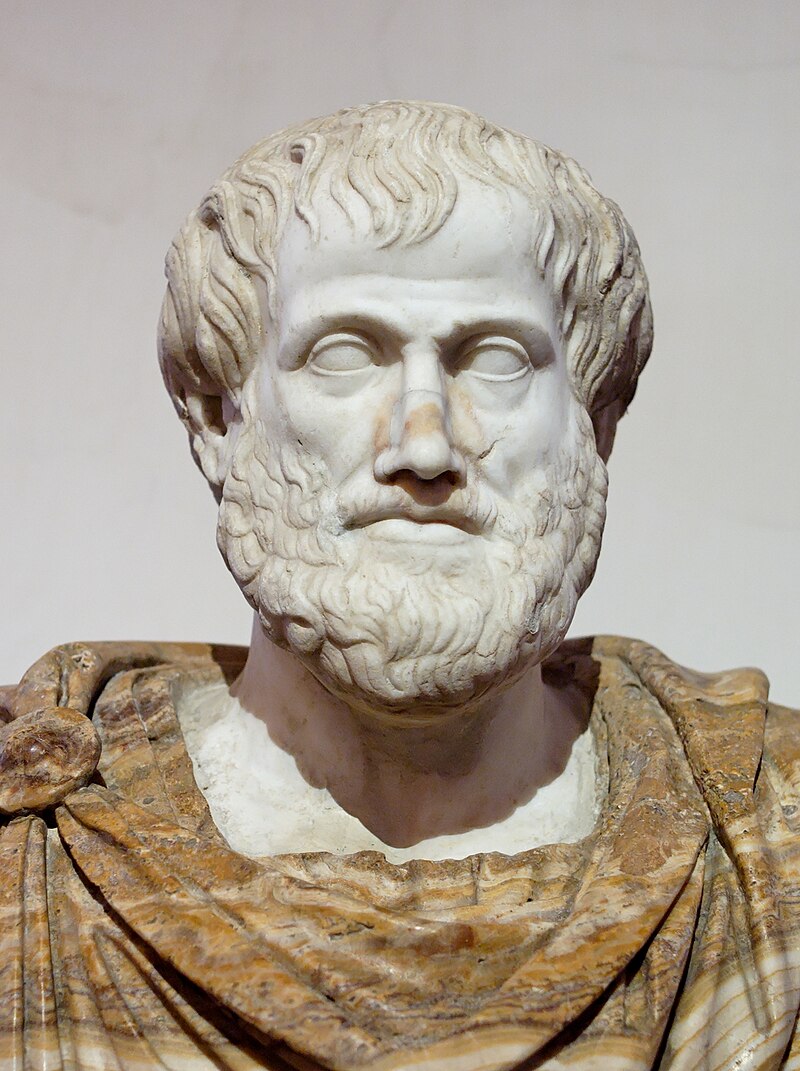

Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle, together with Socrates and Plato, laid much of the groundwork for western philosophy.

Who Was Aristotle?

Early life, family and education.

Aristotle was born circa 384 B.C. in Stagira, a small town on the northern coast of Greece that was once a seaport.

Aristotle’s father, Nicomachus, was court physician to the Macedonian king Amyntas II. Although Nicomachus died when Aristotle was just a young boy, Aristotle remained closely affiliated with and influenced by the Macedonian court for the rest of his life. Little is known about his mother, Phaestis; she is also believed to have died when Aristotle was young.

After Aristotle’s father died, Proxenus of Atarneus, who was married to Aristotle’s older sister, Arimneste, became Aristotle’s guardian until he came of age. When Aristotle turned 17, Proxenus sent him to Athens to pursue a higher education. At the time, Athens was considered the academic center of the universe. In Athens, Aristotle enrolled in Plato ’s Academy, Greek’s premier learning institution, and proved an exemplary scholar. Aristotle maintained a relationship with Greek philosopher Plato, himself a student of Socrates , and his academy for two decades. Plato died in 347 B.C. Because Aristotle had disagreed with some of Plato’s philosophical treatises, Aristotle did not inherit the position of director of the academy, as many imagined he would.

After Plato died, Aristotle’s friend Hermias, king of Atarneus and Assos in Mysia, invited Aristotle to court.

Aristotle’s Books

Aristotle wrote an estimated 200 works, most in the form of notes and manuscript drafts touching on reasoning, rhetoric, politics, ethics, science and psychology. They consist of dialogues, records of scientific observations and systematic works. His student Theophrastus reportedly looked after Aristotle’s writings and later passed them to his own student Neleus, who stored them in a vault to protect them from moisture until they were taken to Rome and used by scholars there. Of Aristotle’s estimated 200 works, only 31 are still in circulation. Most date to Aristotle’s time at the Lyceum.

Poetics is a scientific study of writing and poetry where Aristotle observes, analyzes and defines mostly tragedy and epic poetry. Compared to philosophy, which presents ideas, poetry is an imitative use of language, rhythm and harmony that represents objects and events in the world, Aristotle posited. His book explores the foundation of storymaking, including character development, plot and storyline.

'Nicomachean Ethics' and 'Eudemian Ethics'

In Nichomachean Ethics , which is believed to have been named in tribute to Aristotle’s son, Nicomachus, Aristotle prescribed a moral code of conduct for what he called “good living.” He asserted that good living to some degree defied the more restrictive laws of logic, since the real world poses circumstances that can present a conflict of personal values. That said, it was up to the individual to reason cautiously while developing his or her own judgment. Eudemian Ethics is another of Aristotle’s major treatises on the behavior and judgment that constitute “good living.”

On happiness: In his treatises on ethics, Aristotle aimed to discover the best way to live life and give it meaning — “the supreme good for man,” in his words — which he determined was the pursuit of happiness. Our happiness is not a state but but an activity, and it’s determined by our ability to live a life that enables us to use and develop our reason. While bad luck can affect happiness, a truly happy person, he believed, learns to cultivate habits and behaviors that help him (or her) to keep bad luck in perspective.

The golden mean: Aristotle also defined what he called the “golden mean.” Living a moral life, Aristotle believed, was the ultimate goal. Doing so means approaching every ethical dilemma by finding a mean between living to excess and living deficiently, taking into account an individual’s needs and circumstances.

'Metaphysics'

In his book Metaphysics , Aristotle clarified the distinction between matter and form. To Aristotle, matter was the physical substance of things, while form was the unique nature of a thing that gave it its identity.

In Politics , Aristotle examined human behavior in the context of society and government. Aristotle believed the purpose of government was make it possible for citizens to achieve virtue and happiness. Intended to help guide statesmen and rulers, Politics explores, among other themes, how and why cities come into being; the roles of citizens and politicians; wealth and the class system; the purpose of the political system; types of governments and democracies; and the roles of slavery and women in the household and society.

In Rhetoric , Aristotle observes and analyzes public speaking with scientific rigor in order to teach readers how to be more effective speakers. Aristotle believed rhetoric was essential in politics and law and helped defend truth and justice. Good rhetoric, Aristotle believed, could educate people and encourage them to consider both sides of a debate. Aristotle’s work explored how to construct an argument and maximize its effect, as well as fallacious reasoning to avoid (like generalizing from a single example).

'Prior Analytics'

In Prior Analytics , Aristotle explains the syllogism as “a discourse in which, certain things having been supposed, something different from the things supposed results of necessity because these things are so.” Aristotle defined the main components of reasoning in terms of inclusive and exclusive relationships. These sorts of relationships were visually grafted in the future through the use of Venn diagrams.

Other Works on Logic

Besides Prior Analytics , Aristotle’s other major writings on logic include Categories, On Interpretation and Posterior Analytics . In these works, Aristotle discusses his system for reasoning and for developing sound arguments.

Works on Science

Aristotle composed works on astronomy, including On the Heavens , and earth sciences, including Meteorology . By meteorology, Aristotle didn’t simply mean the study of weather. His more expansive definition of meteorology included “all the affectations we may call common to air and water, and the kinds and parts of the earth and the affectations of its parts.” In Meteorology , Aristotle identified the water cycle and discussed topics ranging from natural disasters to astrological events. Although many of his views on the Earth were controversial at the time, they were re-adopted and popularized during the late Middle Ages.

Works on Psychology

In On the So ul , Aristotle examines human psychology. Aristotle’s writings about how people perceive the world continue to underlie many principles of modern psychology.

Aristotle’s work on philosophy influenced ideas from late antiquity all the way through the Renaissance. One of the main focuses of Aristotle’s philosophy was his systematic concept of logic. Aristotle’s objective was to come up with a universal process of reasoning that would allow man to learn every conceivable thing about reality. The initial process involved describing objects based on their characteristics, states of being and actions.

In his philosophical treatises, Aristotle also discussed how man might next obtain information about objects through deduction and inference. To Aristotle, a deduction was a reasonable argument in which “when certain things are laid down, something else follows out of necessity in virtue of their being so.” His theory of deduction is the basis of what philosophers now call a syllogism, a logical argument where the conclusion is inferred from two or more other premises of a certain form.

Aristotle and Biology

Although Aristotle was not technically a scientist by today’s definitions, science was among the subjects that he researched at length during his time at the Lyceum. Aristotle believed that knowledge could be obtained through interacting with physical objects. He concluded that objects were made up of a potential that circumstances then manipulated to determine the object’s outcome. He also recognized that human interpretation and personal associations played a role in our understanding of those objects.

Aristotle’s research in the sciences included a study of biology. He attempted, with some error, to classify animals into genera based on their similar characteristics. He further classified animals into species based on those that had red blood and those that did not. The animals with red blood were mostly vertebrates, while the “bloodless” animals were labeled cephalopods. Despite the relative inaccuracy of his hypothesis, Aristotle’s classification was regarded as the standard system for hundreds of years.

Marine biology was also an area of fascination for Aristotle. Through dissection, he closely examined the anatomy of marine creatures. In contrast to his biological classifications, his observations of marine life, as expressed in his books, are considerably more accurate.

Wife and Children

During his three-year stay in Mysia, Aristotle met and married his first wife, Pythias, King Hermias’ niece. Together, the couple had a daughter, Pythias, named after her mother.

In 335 B.C., the same year that Aristotle opened the Lyceum, his wife Pythias died. Soon after, Aristotle embarked on a romance with a woman named Herpyllis, who hailed from his hometown of Stagira. According to some historians, Herpyllis may have been Aristotle’s slave, granted to him by the Macedonia court. They presume that he eventually freed and married her. Regardless, it is known that Herpyllis bore Aristotle children, including one son named Nicomachus, after Aristotle’s father.

In 338 B.C., Aristotle went home to Macedonia to start tutoring King Phillip II’s son, the then 13-year-old Alexander the Great . Phillip and Alexander both held Aristotle in high esteem and ensured that the Macedonia court generously compensated him for his work.

In 335 B.C., after Alexander had succeeded his father as king and conquered Athens, Aristotle went back to the city. In Athens, Plato’s Academy, now run by Xenocrates, was still the leading influence on Greek thought. With Alexander’s permission, Aristotle started his own school in Athens, called the Lyceum. On and off, Aristotle spent most of the remainder of his life working as a teacher, researcher and writer at the Lyceum in Athens until the death of his former student Alexander the Great.

Because Aristotle was known to walk around the school grounds while teaching, his students, forced to follow him, were nicknamed the “Peripatetics,” meaning “people who travel about.” Lyceum members researched subjects ranging from science and math to philosophy and politics, and nearly everything in between. Art was also a popular area of interest. Members of the Lyceum wrote up their findings in manuscripts. In so doing, they built the school’s massive collection of written materials, which by ancient accounts was credited as one of the first great libraries.

When Alexander the Great died suddenly in 323 B.C., the pro-Macedonian government was overthrown, and in light of anti-Macedonia sentiment, Aristotle was charged with impiety for his association with his former student and the Macedonian court. To avoid being prosecuted and executed, he left Athens and fled to Chalcis on the island of Euboea, where he would remain until his death a year later.

In 322 B.C., just a year after he fled to Chalcis to escape prosecution under charges of impiety, Aristotle contracted a disease of the digestive organs and died.

In the century following Aristotle’s death, his works fell out of use, but they were revived during the first century. Over time, they came to lay the foundation of more than seven centuries of philosophy. Aristotle’s influence on Western thought in the humanities and social sciences is largely considered unparalleled, with the exception of his teacher Plato’s contributions, and Plato’s teacher Socrates before him. The two-millennia-strong academic practice of interpreting and debating Aristotle’s philosophical works continues to endure.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Aristotle

- Birth Year: 384

- Birth City: Stagira, Chalcidice

- Birth Country: Greece

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle, together with Socrates and Plato, laid much of the groundwork for western philosophy.

- Science and Medicine

- Plato's Academy

- Nationalities

- Death Year: 322

- Death City: Chalcis, Euboea

- Death Country: Greece

We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

- Knowing yourself is the beginning of all wisdom.

- All men by nature desire knowledge.

- A friend to all is a friend to none.

Philosophers

Francis Bacon

Auguste Comte

Charles-Louis de Secondat

Saint Thomas Aquinas

William James

John Stuart Mill

Jean-Paul Sartre

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 13, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

The Greek philosopher Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) made significant and lasting contributions to nearly every aspect of human knowledge, from logic to biology to ethics and aesthetics. Though overshadowed in classical times by the work of his teacher Plato , from late antiquity through the Enlightenment, Aristotle’s surviving writings were incredibly influential. In Arabic philosophy, he was known simply as “The First Teacher.” In the West, he was “The Philosopher.”

Aristotle's Early Life

Aristotle was born in 384 B.C. in Stagira in northern Greece. Both of his parents were members of traditional medical families, and his father, Nicomachus, served as court physician to King Amyntus III of Macedonia . His parents died while he was young, and he was likely raised at his family’s home in Stagira. At age 17 he was sent to Athens to enroll in Plato's Academy . He spent 20 years as a student and teacher at the school, emerging with both a great respect and a good deal of criticism for his teacher’s theories. Plato’s own later writings, in which he softened some earlier positions, likely bear the mark of repeated discussions with his most gifted student.

Did you know? Aristotle's surviving works were likely meant as lecture notes rather than literature, and his now-lost writings were apparently of much better quality. The Roman philosopher Cicero said that "If Plato's prose was silver, Aristotle's was a flowing river of gold."

When Plato died in 347, control of the Academy passed to his nephew Speusippus. Aristotle left Athens soon after, though it is not clear whether frustrations at the Academy or political difficulties due to his family’s Macedonian connections hastened his exit. He spent five years on the coast of Asia Minor as a guest of former students at Assos and Lesbos. It was here that he undertook his pioneering research into marine biology and married his wife Pythias, with whom he had his only daughter, also named Pythias.

In 342 Aristotle was summoned to Macedonia by King Philip II to tutor his son, the future Alexander the Great —a meeting of great historical figures that, in the words of one modern commentator, “made remarkably little impact on either of them.”

Aristotle and the Lyceum

Aristotle returned to Athens in 335 B.C. As an alien, he couldn’t own property, so he rented space in the Lyceum, a former wrestling school outside the city. Like Plato’s Academy, the Lyceum attracted students from throughout the Greek world and developed a curriculum centered on its founder’s teachings. In accordance with Aristotle’s principle of surveying the writings of others as part of the philosophical process, the Lyceum assembled a collection of manuscripts that comprised one of the world’s first great libraries .

Aristotle's Works

It was at the Lyceum that Aristotle probably composed most of his approximately 200 works, of which only 31 survive. In style, his known works are dense and almost jumbled, suggesting that they were lecture notes for internal use at his school. The surviving works of Aristotle are grouped into four categories.

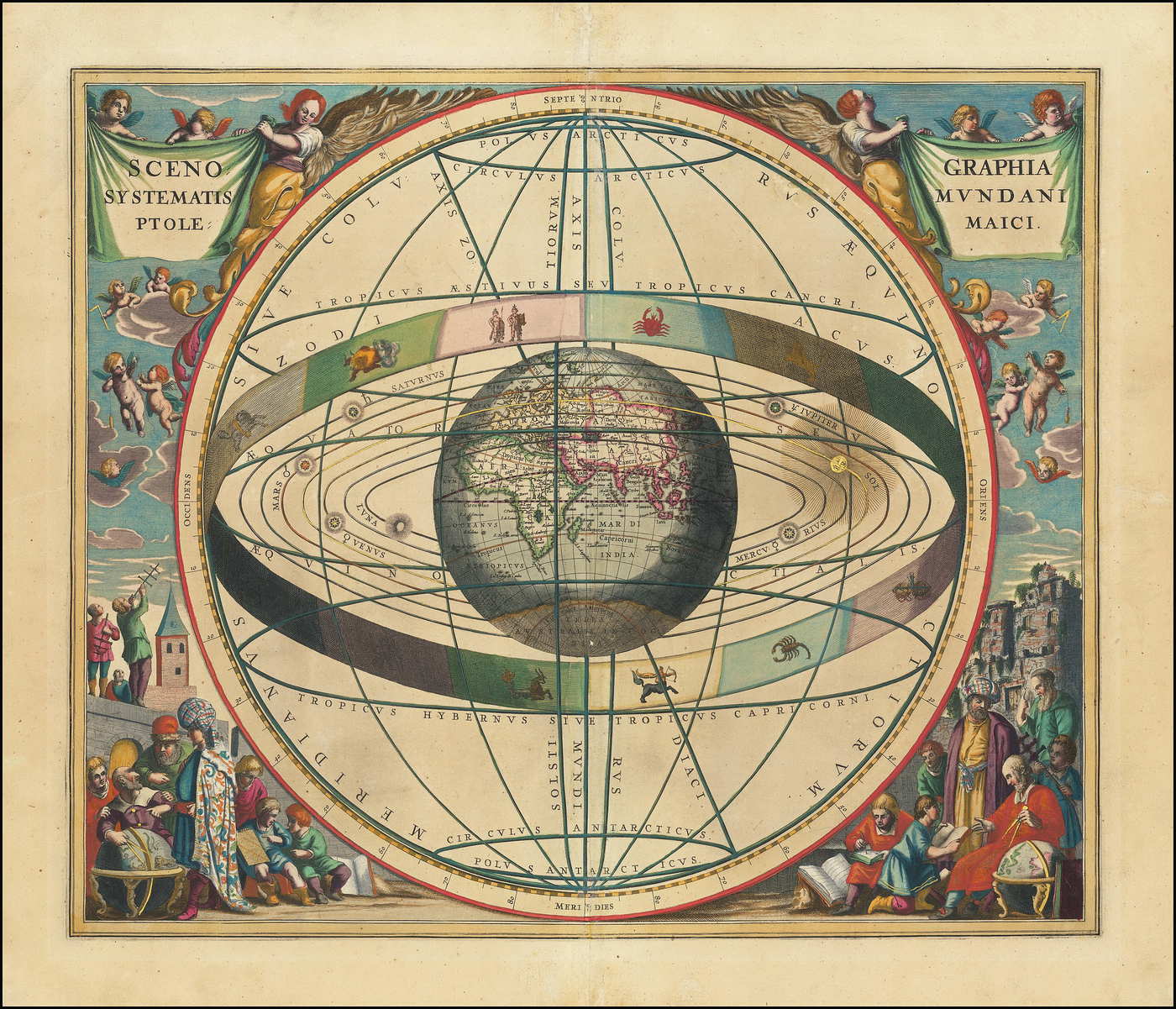

The “Organon” is a set of writings that provide a logical toolkit for use in any philosophical or scientific investigation. Next come Aristotle’s theoretical works, most famously his treatises on animals (“Parts of Animals,” “Movement of Animals,” etc.), cosmology, the “Physics” (a basic inquiry about the nature of matter and change) and the “Metaphysics” (a quasi-theological investigation of existence itself).

Third are Aristotle’s so-called practical works, notably the “Nicomachean Ethics” and “Politics,” both deep investigations into the nature of human flourishing on the individual, familial and societal levels. Finally, his “Rhetoric” and “Poetics” examine the finished products of human productivity, including what makes for a convincing argument and how a well-wrought tragedy can instill cathartic fear and pity.

The Organon

“The Organon” (Latin for “instrument”) is a series of Aristotle’s works on logic (what he himself would call analytics) put together around 40 B.C. by Andronicus of Rhodes and his followers. The set of six books includes “Categories,” “On Interpretation,” “Prior Analytics,” “Posterior Analytics,” “Topics,” and “On Sophistical Refutations.” The Organon contains Aristotle’s worth on syllogisms (from the Greek syllogismos , or “conclusions”), a form of reasoning in which a conclusion is drawn from two assumed premises. For example, all men are mortal, all Greeks are men, therefore all Greeks are mortal.

Metaphysics

Aristotle’s “Metaphysics,” written quite literally after his “Physics,” studies the nature of existence. He called metaphysics the “first philosophy,” or “wisdom.” His primary area of focus was “being qua being,” which examined what can be said about being based on what it is, not because of any particular qualities it may have. In “Metaphysics,” Aristotle also muses on causation, form, matter and even a logic-based argument for the existence of God.

To Aristotle, rhetoric is “the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion.” He identified three main methods of rhetoric: ethos (ethics), pathos (emotional) and logos (logic). He also broke rhetoric into types of speeches: epideictic (ceremonial), forensic (judicial) and deliberative (where the audience is required to reach a verdict). His groundbreaking work in this field earned him the nickname “the father of rhetoric.”

Aristotle’s “Poetics” was composed around 330 B.C. and is the earliest extant work of dramatic theory. It is often interpreted as a rebuttal to his teacher Plato’s argument that poetry is morally suspect and should therefore be expunged from a perfect society. Aristotle takes a different approach, analyzing the purpose of poetry. He argues that creative endeavors like poetry and theater provides catharsis, or the beneficial purging of emotions through art.

Aristotle's Death and Legacy

After the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C., anti-Macedonian sentiment again forced Aristotle to flee Athens. He died a little north of the city in 322, of a digestive complaint. He asked to be buried next to his wife, who had died some years before. In his last years he had a relationship with his slave Herpyllis, who bore him Nicomachus, the son for whom his great ethical treatise is named.

Aristotle’s favored students took over the Lyceum, but within a few decades the school’s influence had faded in comparison to the rival Academy. For several generations Aristotle’s works were all but forgotten. The historian Strabo says they were stored for centuries in a moldy cellar in Asia Minor before their rediscovery in the first century B.C., though it is unlikely that these were the only copies.

In 30 B.C. Andronicus of Rhodes grouped and edited Aristotle’s remaining works in what became the basis for all later editions. After the fall of Rome, Aristotle was still read in Byzantium and became well-known in the Islamic world, where thinkers like Avicenna (970-1037), Averroes (1126-1204) and the Jewish scholar Maimonodes (1134-1204) revitalized Aritotle’s logical and scientific precepts.

Aristotle in the Middle Ages and Beyond

In the 13th century, Aristotle was reintroduced to the West through the work of Albertus Magnus and especially Thomas Aquinas, whose brilliant synthesis of Aristotelian and Christian thought provided a bedrock for late medieval Catholic philosophy, theology and science.

Aristotle’s universal influence waned somewhat during the Renaissance and Reformation , as religious and scientific reformers questioned the way the Catholic Church had subsumed his precepts. Scientists like Galileo and Copernicus disproved his geocentric model of the solar system, while anatomists such as William Harvey dismantled many of his biological theories. However, even today, Aristotle’s work remains a significant starting point for any argument in the fields of logic, aesthetics, political theory and ethics.

HISTORY Vault: Ancient History

From the Sphinx of Egypt to the Kama Sutra, explore ancient history videos.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Aristotle, His Life and Philosophical Ideas Essay (Biography)

Aristotle is considered to be one of the greatest Greek philosophers that ever lived according to the Encyclopedia of Classical philosophy (1997).

He lived between 384 B.C. and 322 B.C. having accomplished a lot in philosophy and all other fields of Education. At the age of seven, he joined Plato’s academy where he became one of his favorite student. He later on became a researcher then a teacher in the same institution. In his life, he taught Alexander the Great who at the time was thirteen years of age, at the invitation of his father King Phillip II.

This great philosopher was born in a town called Stageira in Chalcidice. Later on at the age of eighteen, he moved to Athens to study and this became his home for the next twenty years, after which he moved to Asia after the death of Plato where he concentrated in the study of biology at Lesbos Island. In fact, Meet the Philosophers of Ancient Greece (2005) indicates that he conducted most of his research in this period.

There are a number of significant events which took place during the times of Aristotle and which had an impact in his life. In Athens where he had lived for almost twenty years, there was the anti-Macedonia uprising around 347 B.C. which led to a series of political unrests. Being of Macedonian origin, he was forced to flee the country as indicated in The Columbia Encyclopedia (2008). Later on, King Philip came to power and restored peace between Macedonia and Athens, a gesture that saw to the return of peace. In 323 B.C. however, the political unrest revived again after the rule of Alexander the Great came to an end. Aristotle was considered to be a great sympathizer of Alexander and these latter revolts were directly focused on him. He was charged with blasphemy and forced to flee the country together with his family (Bryant 1996).

With the help of other scholars, Aristotle was able to establish his own school, the Lyceum which was later renamed to Peripatetic. According to the Encyclopedia of classical philosophy (1997), Alexander the Great who was one of Aristotle’s students “financed his research in Peripatetic and had ordered hunters, fishermen, bird-catchers, beekeepers and other professionals to convey to Aristotle any information of scientific interest” (pg 1).

The coming down of Alexander’s reign had negative effects to the life of Aristotle since it caused a security threat forcing him to flee (Bechler 1995). Besides this the death of Plato also caused a major turn of events in the life of Aristotle. This owes to the fact that he left the Academy and started working on his own philosophical dissertations.

After fleeing Athens in 323 BC, Aristotle’s life came to an end in 322 BC after an ailment of the digestive organs (Bar and Bat 1994). His work was considered as the most influential in the world of philosophy and was widely used between the period of antiquity and renaissance. He had a great influence in the western world especially with regards to social sciences and humanities and some of the ideas he developed are still debatable to date.

Aristotle was famous for a number of philosophical theories some of which survived while others were faced out. According to the Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy (1999), a majority of his work was geared towards the public and it is believed that Plato played a big role in these writings.

There are however others which are historical in nature such as the Constitution of the Athenians, a piece that was used by his students in the study of political theories. Despite the fact that most of his writings got lost, the ones that survived are still considered the best writings of the time (Anton, George and Anthony 1971).

One of Aristotle’s most famous theories was the metaphysics. In this theory, he argues that “all investigation must begin with what the senses record and must move only from that point to thought” (Stern 1995, pg 4). The term metaphysics is directly interpreted to ‘what comes after physics’.

According to the Cambridge dictionary of philosophy , there were two conditions to this theory. The first one indicated that objects which were widely known needed to exist separately from the non-sensible objects. The second condition on the other hand had it that the objects which were known were just a generalization of objects.

The other theory developed by Aristotle was that of Practical philosophy . This was stipulated in two of his works namely the Nicomachean Ethics and the politics. The main aim of this was to bring out the best actions in issues related to conduct (Ferrarin 2001). As a result of this, he developed the Nicomachean Ethics as a reminder of the principle of becoming good and not just knowing what is good.

In this philosophy, he went ahead to explain that good people made that choice at one point or the other and not just the actions but the right way of performing those actions as well. He explained different types of individuals; the akratic being one who decides to act contrary to what they know is right out of desire while the enkratic despite feeling like they want to act contrary decide to take the right action.

Another philosophical theory that was brought forth by Aristotle was that of psychology. One of his writings, on the soul provided a universal interpretation of the nature and quantity of cognitive faculties principles of the soul. Other writings such as the Parva naturalia made use of the universal theory to a wide variety of psychological occurrences ranging from sleeping, dreaming and waking to memory and reminiscence (Bryant 1996).

He went ahead and subdivided the capacity to perform different actions into either potentiality or actuality. He explained potentiality as an inborn characteristic in an organism by virtue of it belonging to a specific species. Actuality on the other hand is gained through training and experience in that particular field.

The ideas developed by Aristotle were unique in their own ways. In the development of his theories he tried to bring the natural way of occurrences in to the thinking and actions of living creatures and specifically humans. As a result of this, his theories were subject to less disapproval since they were self-supportive.

The other significant element about these theories was that they remained relevant long afterwards, owing to his extensive research in the different fields. This implies that his ideas were viable in a way that has not been countered by any other scholars so far.

The philosophical ideas and theories developed by Aristotle were mainly influenced by his predecessors such as Socrates and Plato. Plato was his teacher earlier in life and he got an inspiration in mathematics while in the academy. He however opposed some of the speculations made by Plato but later on came to understand these ideas and incorporated some of them in his theories.

The other great influence to the development of Aristotle’s theories was Socrates who died long before Aristotle was born and who also happened to be Plato’s teacher ( Essentials of Philosophy and Ethics 2006 ). Socrates was among the original authors of Greek philosophies and made a great contribution to the development of ethics as a discipline. Aristotle built his theory of ethics on this hence making Socrates an important figure in his work.

The philosophical theories developed by Aristotle acted as the main guidelines to human living at the time. These philosophies played a major role in ensuring co-existence in a place where there were no laid down rules. The theory on ethics for example ensured that people were able to develop behavioral habits that were less of a bother to other people around them. These theories also had an impact on the future since they formed the foundation of the present day education system (Bodaeeus 1993).

Other scholars who came after Aristotle were developing their theories from what Aristotle had already researched on. He also pioneered the issue of gender equality by insisting that women needed to be happy just like their male counterparts. Some of the people who were directly influenced by Aristotle include Aristoxenus, Harpalus, Nichomacus and Dicaerchus among others, all of whom were students at the Lyceum.

Works Cited

Anton, John Peter, George L. Kustas, and Anthony Preus. Essays In Ancient Greek Philosophy . n.p.: State University of New York Press, 1971. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) . Web.

“Aristotle (384-322 B.C.E.).” Encyclopedia of Classical Philosophy. Westport: Greenwood, (1997). Credo Reference. Web.

“Aristotle (384 – 322 B.C.).” The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, (1999). Credo Reference. Web.

“Aristotle (384–322 BCE).” The Essentials of Philosophy and Ethics. Abingdon: Hodder Education, (2006). Credo Reference. Web.

“Aristotle.” The Columbia Encyclopedia. New York: Columbia University Press, (2008). Credo Reference. Web.

Bar On and Bat Ami. Engendering Origins: Critical Feminist Readings In Plato And Aristotle . n.p.: State University of New York Press, 1994. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) . Web.

Bechler, Zeafer. Aristotle’s Theory Of Actuality . n.p.: State University of New York Press, 1995. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) . Web.

Bodaeeus, Richard. The Political Dimensions Of Aristotle’s Ethics . n.p.: State University of New York Press, 1993. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) . Web.

Bryant, Joseph M. Moral Codes And Social Structure In Ancient Greece : A Sociology Of Greek Ethics From Homer To The Epicureans And Stoics . n.p.: State University of New York Press, 1996. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) . Web.

Ferrarin, Alfredo. Hegel And Aristotle . n.p.: Cambridge University Press, 2001. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) . Web.

“Introduction.” Meet the Philosophers of Ancient Greece. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing, (2005). Credo Reference. Web.

Stern-Gillet, Suzanne. Aristotle’s Philosophy Of Friendship . n.p.: State University of New York Press, 1995. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) . Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, June 15). Aristotle, His Life and Philosophical Ideas. https://ivypanda.com/essays/aristotles-life/

"Aristotle, His Life and Philosophical Ideas." IvyPanda , 15 June 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/aristotles-life/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Aristotle, His Life and Philosophical Ideas'. 15 June.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Aristotle, His Life and Philosophical Ideas." June 15, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/aristotles-life/.

1. IvyPanda . "Aristotle, His Life and Philosophical Ideas." June 15, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/aristotles-life/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Aristotle, His Life and Philosophical Ideas." June 15, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/aristotles-life/.

- New York City Article at Wiki vs. New World Encyclopedia

- Socrates by Aristophanes and Plato

- Socrates Influence on Plato’s Philosophy

- Greek Philosopher Socrates

- Athens Put Socrates and Philosophy on Trial

- Information About Socrates: Analysis

- Aristotle's Philosophical Theories

- Compare and Contrast: Plato and Aristotle Essay

- Plato vs. Aristotle: Political Philosophy Compare and Contrast Essay

- Socrates as a Founder of Western Philosophy

- Nicomachean Ethics by Aristotle

- Theory between Economics and Ethics. Adam Smith 'Problem'

- John Locke: His Ideas in The Second Treatise and Contemporary Development

- Comparison of Descartes’ “Meditation” and Plato’s “Phaedo”

- Corrections

Aristotle: A Complete Overview of His Life, Work, and Philosophy

Aristotle is one of the most influential thinkers in the history of Western philosophy. But how much do you really know about this ancient philosopher?

As Plato’s student and Alexander the Great’s teacher, Aristotle left a lasting impact on Western philosophy. He has shaped today’s perceptions of philosophy with his teachings on ethics and logic and thoughts on politics and metaphysics. His philosophy has been both scrutinized and venerated for years, thereby establishing him as an essential personality in Western philosophy.

From discussing topics like ethics to exploring concepts like metaphysics and politics, Aristotle’s writings had a profound influence that endures to this day. Let’s explore Aristotle’s life, his teachings, and their legacy!

Who Was The Great Philosopher Aristotle?

Aristotle (384 – 322 BC) was a renowned ancient Greek philosopher who greatly influenced the world of philosophy, science, and logic. He is considered one of the most influential figures in the history of Western thought.

His works have been pivotal in developing metaphysics , ethics, politics, biology, and aesthetics. In addition, he famously wrote about topics such as natural philosophy, logic, and rhetoric which were studied extensively by many later philosophers.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription.

Aristotle was born in 384 BC in a doctor’s family, which is likely why his future works would also focus on physiology and anatomy. At 15, he became an orphan, and his uncle, who took the boy under his guardianship, told him about the already famous teacher at that time— Plato in Athens.

At 18, Aristotle independently reached Athens and entered the academy of Plato, whose admirer he had already been for three years. Due to his talent and success in scientific activity, Aristotle was given a teaching position in the academy.

In 347 BC, after the death of Plato, Aristotle moved to the city of Assos. Five years later, the Macedonian King Philip invited the philosopher to educate his son Alexander .

In 339 BC, Philip died, and the heir no longer needed lessons, so Aristotle returned to Athens, now a popular and well-known scholar, largely due to his connection to the royal court.

Contribution-wise, Aristotle played an important role in developing both zoology and anatomy via various research methods. He gained recognition for his exceptional contributions to fields like zoology by creating an animal classification system that factored in both physical traits and habits.

In addition to receiving credit for having revolutionized military tactics at that moment in history, another tremendous feat achieved by Aristotle was passing on this knowledge to Alexander The Great . His contribution to military strategy has been commended through time, resulting in his recognition as a brilliant strategist.

Aristotle’s Writings & Works

Aristotle is highly esteemed for his significant contributions across a vast range of human knowledge fields. His numerous written works have profoundly impacted philosophy, science, mathematics, and more.

Aristotle’s The Nicomachean Ethics is a significant work where he presents his theory on the appropriate way to live life. It explores the concept of virtues and their contribution to leading a satisfying life.

Another prominent example is Aristotle’s Politics . In this groundbreaking work, the author explains his political views, including the state’s role, what citizenship should be, and different types of government systems. He claims that the ideal state should be based on a constitution that respects the needs and desires of its citizens.

Another famous work by Aristotle is his Poetics . This piece is considered to be the first work on literary criticism, interpreting and analyzing the genre and structure of Greek literature. It has influenced the study of literature, film, and other art forms. Aristotle discussed the effects of plot, character, and tragedy on audiences to better understand how these devices can be used effectively.

Aristotle is also widely known for his works in the natural sciences. One of the most popular ones is the Metaphysics . This work deals with the fundamental issues of reality, including the study of existence, causality, and substance.

Relatedly, another one of his famous works is named Physics . It laid out his views on motion, time, space, and other important concepts later built upon in the scientific revolution.

Aristotle’s numerous works have made a lasting impact on history by providing valuable insights and knowledge to humanity. They have helped us gain a better understanding of our world, and continue to be discussed in academic and non-academic contexts alike.

Aristotle Was A Student Of Plato

One important fact already stated is that Aristotle was a student of Plato and is widely considered his most illustrious student.

Plato (c. 428 – c. 348 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher who was one of the preeminent minds in Western philosophy, laying down foundations for many areas such as epistemology, metaphysics, and political theory through his numerous dialogues and other works.

While studying at the Academy based in ancient Athens, Aristotle grew intellectually under mentorship from its founder – Plato—hence cementing its status as one of antiquity’s foremost places of advanced studies.

Some of Aristotle’s most prominent works, like Metaphysics and Nicomachean Ethics , discussed various topics, including metaphysics, ethics, or morality, as well as communication through the spoken word—known as rhetoric .

The combination of Aristotle’s education under Plato and his own personal research made him a key figure in philosophy due to his logical yet creative approach to arguments and reasoning. His writing has been fundamental in the formation of traditional thought up until modern times, making him one of the most influential thinkers ever known.

Aristotle’s Style Of Teaching

Aristotle’s pedagogy emphasized using the Socratic method for stimulating dialogue, ideas generation, opinion sharing, and conclusion building. The method focused on dialogues between the teacher and student to generate new ideas, express opinions and reach conclusions.

This was done by starting with a given problem or premise and then questioning it, with each student considering alternate solutions or alternative interpretations.

For example, when teaching, Aristotle might ask his students: “If we assume that all men are mortal, what does this imply about our understanding of Socrates?” Then, through further questioning, he would lead his students to conclude that Socrates is mortal.

In this way, the Socratic method allowed for deeper learning through active participation and discourse from both the teacher and the students.

By prioritizing logic over traditional sources of information like doctrine or custom when arriving at conclusions, Aristotle effectively shaped subsequent philosophical movements.

This influence would even stretch centuries into the future, with figures like Cicero and Augustine citing his work, which is still taught in schools and universities today.

Teaching Alexander The Great

When Alexander the Great was a teenager, his father, Philip II, turned to the famous philosopher of the time, Aristotle, with a request to become his son’s teacher. Aristotle agreed to be Alexander’s teacher on one condition: if Philip restored his hometown of Stagira, which had been destroyed by the Macedonian king.

In that short time (343-340 BC), when the great thinker was Alexander’s teacher, he managed to instill in him a love for philosophy, art, and poetry, which acted as a catalyst in shaping the personality of a young man.

But the Homeric epic Iliad especially influenced Alexander. With the help of this work about the Trojan War, the philosopher found a good means for educating military prowess in his ward. This book accompanied Alexander throughout his short life.

Aristotle taught in the classroom about the duties of rulers and the art of government. He tried to develop the ability to perceive various factors, analyze them, and then make a decision. In addition, he enriched the young ruler with scientific knowledge in the lessons of physics, biology, mathematics, medicine, and geography.

The philosopher was preparing the future ruler so that he would become a full-fledged individual.

Aristotle Gave Us Scientific Reasoning

Aristotle was a pioneering figure in the development of scientific reasoning . By combining his deep knowledge of philosophy, biology, and physics—he laid out the foundations for modern science by advocating for empirical observation, testing, and experimentation to draw meaningful conclusions.

While other philosophers tended towards deriving explanations from religious beliefs or authoritative sources, he stood out due to the emphasis on his analytical abilities tempered with insights into causation.

For instance, Aristotle postulated about natural phenomena, including the behavior of falling objects and species distribution in nature, which later became foundational concepts of classical physics.

To document animal behavior and analyze anatomy, Aristotle produced a multitude of writings on biology for future generations to learn from.

By careful observation, he deduced that every living organism was made up of equivalent elemental constituents. This served as a prefatory notion behind present-day notions concerning evolution and genetics .

Aristotle’s methodical approach to understanding nature left an indelible mark on human thinking. Scientific reasoning has since revolutionized how we understand and interact with our environment; from advances in medicine to space exploration, but Aristotle’s approach to problem-solving has had a lasting legacy.

Aristotle Laid The Foundation For A System Of Logic

Aristotle’s most invaluable and lasting contribution to the world of knowledge was undoubtedly his development of syllogistic logic . He coined the term “ logic ,” emphasizing logical relations between terms in reasonable conclusions. His approach to understanding philosophy and our conception of reality endeavored to explain how we think and develop ideas.

Aristotle’s landmark work, Prior Analytics , put forth syllogism as his chief logical contribution. Syllogisms are modes of reasoning that involve specific assumptions or premises from which a conclusion can be drawn. This logic system marked the starting point for much of our current understanding of argumentation processes.

Moreover, Aristotle presented rules for appropriate reasoning, such as the law of non-contradiction, which expresses that two conflicting statements cannot simultaneously be true. This principle is still recognized as true today in many disciplines, including mathematics and science.

From its inception, Aristotle’s work on logic has been a driving force throughout the ages. Its pervasive impact can be seen in our modern-day understanding of philosophy and knowledge.

His contributions inform us about how we think and enable us to make more rational decisions concerning ourselves and our environment. Truly, his legacy will remain with us for generations to come!

Aristotle Established The Principle Of Inductive Reasoning

Establishing the principle of inductive reasoning is one of Aristotle’s credited accomplishments. Inductive reasoning involves drawing general conclusions from specific observations and experiences. Generalizing fetched evidence helps us draw closer-to-truth conclusions, even if they’re not completely certain.

Aristotle first proposed the concept of induction in his book Prior Analytics . Initially described by Aristotle, induction involves collecting factual data and formulating hypotheses accordingly before reconciling them with further empirical research. Modern logic and systematic research owe much to this groundbreaking theory.

Starting from concrete observations up to developing more theoretical concepts is how inductive logic works differently than deductive logic, which goes straight from theory to specifics. This approach has been incredibly valuable in advancing scientific inquiry by eliminating false premises from the discussion.

Aristotle was a pioneer in many aspects of philosophy. Still, his establishment of the principle of inductive reasoning stands as one of his most significant contributions to our understanding of how knowledge is best acquired and evaluated.

Aristotle Was A Biologist Even Before There Was Biology

Before the formal practice of biology existed, Aristotle showed a remarkable talent for observing and classifying living things. Combining keen observations with philosophy, Aristotle established himself as an early maker of modern-day biological knowledge before it became more established and formalized.

Aristotle is rightly considered the creator of biology as a science. Several of his works are devoted to the problems of biology: The History of Animals , On the Parts of Animals , On the Origin of Animals , On the Movement of Animals , and a small essay, On the Walking of Animals .

In addition to these special works, which treat questions of zoology, the first two books of On the Soul are also devoted to the problem of life and the living.

In works devoted to the study of wildlife, the “empirical component” is especially striking: the philosopher relies both on his observations and on the vast experience gleaned from the practice of contemporary agriculture, fishing, etc.

Judging by his writings, Aristotle collected information about animals primarily from fishermen, shepherds, beekeepers, pig breeders, and veterinarians.

It should be noted that the philosopher shared some of the prejudices of his time, believing, for example, that males are warmer than females and the right side of the body of animals is warmer than the left.

In humans, he believed, the left side of the body is colder than in other living beings, so the heart is shifted to the left to balance the temperature of both sides of the body.

Aristotle’s pioneering work in biology and his insistence on empirical observation exemplify the power of scientific inquiry. Thanks to his observatory approach toward life sciences, many biologists have—a couple of millennia later—decoded nature’s clandestine ways.

Aristotle “Invented” the Field of Economics

The economic views of Aristotle are not separated from his philosophical teachings. They are woven into the general theme of reasoning about the foundations of ethics and politics (and, more broadly, how people and the state should be managed).

In his treatises, one can see the desire to single out and understand certain categories and connections that later became the subject of political economy as a science.

For example, in Aristotle’s time, the basis of wealth and the main source of its increase were slaves. Aristotle called slaves “the first object of possession,” so he advised that care must be taken to acquire good slaves who can work long and hard.

Barter trade’s evolution into large-scale commerce through history was also a subject matter Aristotle examined extensively. He tried with great persistence to understand the laws of exchange.

Aristotle’s focus was on comprehending how barter trade transformed into large-scale operations through historical analysis. Large-scale trade facilitated and contributed to state formation.

Aristotle approved of the type of management that pursued the goal of acquiring goods for the home and the state, calling it “economy.” The economy is associated with the production of products necessary for life. The activities of commercial and usurious capital, aimed at enrichment, he characterized as unnatural, calling it “ chrematistics .”

Chrematistics is focused on making a profit and primarily aims at the accumulation of wealth. Aristotle argues that trading in commodities is not part of chrematistics because it only involves exchanging objects necessary for buyers and sellers.

Therefore, the original form of commodity profit was barter, but with its expansion, money necessarily arises. With the invention of money, barter must inevitably develop into commodity trade. The latter turned into chrematistics, the art of making money.

Arguing in this way, Aristotle concludes that chrematistics is built on money since money is the beginning and end of any exchange.

Therefore, Aristotle tried to determine the nature of these two phenomena (economics and chrematistics) to determine their historical place. On this path, he was the first to distinguish between money as a simple means of enrichment and money that has become capital.

Aristotle’s Views On Death And The Afterlife

Aristotle, who considered the ability to think about death an indispensable condition for active happiness and a wonderful life, did not try to embellish the bitter truth. On the contrary, he believed death was the worst thing because this was the limit.

The philosopher knew that many of his readers believed in an afterlife . We can find hints that his ethics were compatible with a belief in the so’s immortality in a dialogue designed to console those mourning the heroic death of a Cypriot named Evdem, who did not belong to philosophical circles.

But Aristotle, like most of today’s atheists and agnostics, certainly considered death final and irrevocable. Immortality can be desired, he says in Nicomachean Ethics , but it is not given to a person to consciously choose it.

Aristotle believed life and death are not opposites but two parts of a natural process. He theorized that when a person dies, their soul leaves their body and enters either the celestial realm or Hades —depending on whether they had lived virtuously or unvirtuously during their lifetime.

The souls in the celestial realm would enjoy an eternal existence full of happiness, wisdom, and moral fulfillment. At the same time, those who lived a more unvirtuous life would be doomed to an eternity of instability and suffering within Hades.

Aristotle also thought that certain spiritual objects, such as friendship, love , knowledge, and beauty, could exist beyond physical death. Furthermore, he believed that these non-physical forms were immutable and could, therefore, never perish.

Aristotle’s Views On Justice / Equality

Aristotle also expressed his views on justice in Nicomachean Ethics . For him, justice is the equalization of one’s own interest with the interests of others. The task of justice is to serve society, and if the law is violated, it is a crime.

According to the philosopher, actions consistent with justice and contrary to it can be of two types: they can affect one person or the whole society. A person who commits adultery and inflicts beatings is doing injustice to one particular person, and a person who evades military service is doing injustice to society.

For Aristotle, justice is a principle that regulates relations between people regarding the distribution of social values. The ancient Greek philosopher points out the differences between justice and injustice.

He believed that justice is retribution to everyone for his merits. Injustice is arbitrariness that violates human rights. Objective decisions are fair. It is unfair to transfer one’s own responsibilities to others and receive benefits at the expense of others.

Aristotle distinguishes two types of justice—comparative and distributive. Comparative justice implies a comparison of actions between people, and distributive justice focuses on the equitable distribution of social resources to all members of society.

Aristotle’s views on justice are not dissimilar from those of modern society, as he believed that law should be based on equality and applied to all people without discrimination. He also argued that justice should work for the benefit of all it affects.

Aristotle’s Views On Politics

Aristotle plunged into politics with the same passion with which he studied nature and ethics. Aristotle considered man a “political animal” ( zoon politikon ), which acquires its true essence only in community with other people. In his opinion, a person must live in a political society to be complete and happy.

According to Aristotle, the ideal state should be neither too big nor too small so that citizens can personally participate in political life and follow justice. Furthermore, Aristotle taught that the best way of life and government is the golden mean between extremes.

Thus, an ideal state is a place where the interests of different social strata are balanced, and no one group dominates the others.

Aristotle did a great job of studying the history and experience of different forms of government to understand what kind of government best promotes the common good. In his Politics , he analyzes over 150 city-states and their constitutions.

Aristotle argued that a good state should provide education for all its citizens since educated people can better serve their state and live in harmony with laws and morals. For the philosopher, politics was an art and science to secure a just common good.

Aristotle’s Views On Slavery

Aristotle’s singular approach toward envisaging enslavement as a crucial piece of historical community sets him apart. He viewed slavery as a necessary phenomenon in the social structure. That said, his viewpoint was detailed and layered, though unacceptable by today’s ethical standards.

According to the thinker, there exist segments of the human population that are predestined by nature towards servitude. In his opinion, slaves had physical abilities but could not manage their lives or make decisions. So, those born as slaves required leadership from the wise.

One of Aristotle’s beliefs was that slavery actually proved advantageous for both masters and slaves alike. He believed that slavery was advantageous for slave owners and slaves alike because, he argued, masters provided protection and provision to their slaves in exchange for their labor and services.

Aristotle also acknowledged that slaves could be “improved” through the upbringing they received from their masters. In his view, the masters are responsible for teaching the slaves virtues and discipline.

Part of a slave’s improvement process involved learning from their master how to live virtuously, leading them to become more independent individuals with greater responsibilities towards society.

Aristotle’s Views On Women

Aristotle’s views on women became influential in the further development of philosophy and thoughts of future thinkers until the end of the Middle Ages. In his treatise on state Politics , Aristotle defined women as the subordinate sex to men.

As stipulated by Aristotle, according to his beliefs expressed within Politics —when males maintained dominance over politics—females were considered higher class individuals when compared with slaves.

Among the notable features of women were: expansiveness, compassion, and naivety, which also hindered them in political life.

However, in writing Rhetoric , Aristotle put women’s happiness on the same level of importance as men’s because he believed it is impossible to achieve general happiness in society if some segments of the population remained dissatisfied.

Aristotle believed that men and women possess differing levels of intelligence and physiological distinctions. Some recent studies have shown that memory strength may vary between genders, though the reasons for this are unclear.

Besides, the thinker said that fair-skinned women, but not black-skinned women, can climax during sex. Aristotle believed women were more passionate than men despite having weaker intellects.

Overall, even though it might not seem that way, Aristotle’s views on women were somewhat progressive for his time. Aristotle’s outlook on female empowerment and rights was somewhat liberal for its period; nevertheless, it remained insufficiently evolved compared with present-day perspectives.

Aristotle’s Views On Homosexuality

With a discussion of homosexuality in the Nichomachean Ethics , Aristotle was one of the first early Ancient Philosophers who shared their thoughts on this topic.

He proposed that one’s ability and character should outweigh their sex when it comes to making friends. Aristotle asserted that a gentleman should not feel attracted to someone of the same sex if their relationship is solely based on physical pleasure, which would go against nature’s purpose for human sexuality.

Homosexual behavior might cause a man to act against his nature, thus leading him toward moral wickedness.

While generally expressing disapproval of such relationships, the author also recognized their potential benefits in boosting a person’s physical and emotional wellness whenever the relationship is based on genuine mutual affection.

Despite holding these relatively open attitudes towards homosexuality compared to other ancient thinkers, it’s clear that Aristotle still viewed it as primarily something harmful or unnatural. This reflects the prevailing attitudes towards LGBT+ people during his lifetime. Nevertheless, contemporary societal standards classify these views as obsolete and morally questionable.

So, Who Was The Great Philosopher Aristotle?

As a renowned philosopher and polymath from ancient Greece, Aristotle’s contributions have influenced fields including politics, logic, science, mathematics, and philosophy.

Aside from his groundbreaking contributions in these fields, he authored several works on various subjects like ethics, politics, morality, etc., which many scholars continue to study today.

Looking at reality and considering the philosophical disputes prevalent during his time formed Aristotle’s foundation for philosophy. Throughout the Middle Ages, Aristotle’s perspective towards topics such as homosexuality, slavery, and women has been considered influential for later scientific thought.

That being said, most people now regard Aristotle’s beliefs about slavery, homosexuality, and women as archaic.

The level of admiration directed towards Aristotle persists even today because of his extraordinary intelligence and the breadth of his work. He managed to organize and deepen the lessons of his ancestors and lay them out into a large number of works that, fortunately, remain available to us to this day.

Therefore, Aristotle made a far-reaching arrangement of theories, covering all areas of human thought and interest, from what would later become the topics of social sciences and governmental issues to physical science and rationality.

What Was Aristotle’s Opinion on Metaphysics?

By Viktoriya Sus MA Philosophy Viktoriya is a writer from L’viv, Ukraine. She has knowledge about the main thinkers. In her free time, she loves to read books on philosophy and analyze whether ancient philosophical thought is relevant today. Besides writing, she loves traveling, learning new languages, and visiting museums.

Frequently Read Together

Aristotle’s Rhetoric: A Brief Overview

What did Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle Think About Wisdom?

Alexander the Great: The Accursed Macedonian

Culture History

Aristotle (384-322 BCE) was a Greek philosopher and polymath. He was a student of Plato and the teacher of Alexander the Great. Aristotle made significant contributions to various fields, including ethics, metaphysics, biology, physics, and politics. His works laid the foundation for Western philosophy and had a profound influence on the development of scientific thinking.

Aristotle’s early life, spanning from his birth in 384 BCE to his years as a student in Plato’s Academy, played a crucial role in shaping the intellectual giant he would become. Born in the ancient Greek city of Stagira, located in the northern part of the Aegean Sea, Aristotle belonged to a family with connections to medical practice. His father, Nicomachus, was the court physician to King Amyntas II of Macedon, providing Aristotle with a background that would later intersect with his own pursuits in natural sciences.

The loss of his parents at an early age, with his mother dying when he was a child and his father’s death during his adolescence, compelled Aristotle to navigate the challenges of life independently. This period of personal loss likely contributed to the development of his resilience and self-reliance, traits that would be evident in his later endeavors.

As a young man, Aristotle made his way to Athens, the intellectual hub of ancient Greece, to pursue education. This decision marked the beginning of his association with one of the most influential philosophers in history—Plato. In Athens, Aristotle entered Plato’s Academy around 367 BCE. The Academy, founded by Plato, was a center of philosophical inquiry and learning, attracting scholars from various regions.

Under Plato’s tutelage, Aristotle delved into the intricacies of philosophy, absorbing the teachings of his revered master. However, philosophical differences began to emerge between them, laying the groundwork for Aristotle’s eventual divergence from Plato’s idealistic views. While Plato emphasized the world of eternal Forms as the ultimate reality, Aristotle, with a more empirical mindset, leaned towards a focus on the observable world and the study of nature.

Despite these differences, Aristotle’s time in the Academy significantly influenced his intellectual development. It was during these formative years that he honed his analytical skills and acquired a profound understanding of philosophical inquiry. The dialogues and debates within the Academy provided Aristotle with a rich intellectual environment that fostered critical thinking and dialectical reasoning.

Following Plato’s death in 347 BCE, Aristotle’s trajectory took a new turn. Though he was considered as a potential successor to lead the Academy, differences in philosophical approach and perhaps the shadow of Plato’s legacy led to his departure from Athens. Aristotle embarked on a journey that would take him to various regions, including a period spent as the tutor to a young Alexander the Great.

This tutoring role proved to be instrumental in Aristotle’s life. The education of Alexander, who would later become one of history’s most renowned military leaders, allowed Aristotle to delve into a wide range of subjects, including ethics, politics, and natural sciences. The Macedonian court provided Aristotle with resources and opportunities to engage in extensive research and exploration, contributing to the breadth of his later works.

After Alexander’s conquests, which expanded Greek influence across vast territories, Aristotle returned to Athens in 335 BCE. It was during this period that he founded his own school, the Lyceum, marking a significant chapter in his educational legacy. The Lyceum, often referred to as the Peripatetic School due to Aristotle’s habit of walking while lecturing, became a center for learning and intellectual discourse.

In contrast to the more exclusive nature of Plato’s Academy, the Lyceum welcomed a diverse array of students. Aristotle’s teaching style was characterized by a systematic and methodical approach, covering a wide range of subjects. He lectured on topics ranging from ethics and politics to biology and metaphysics, reflecting the interdisciplinary nature of his intellectual pursuits.

Aristotle’s commitment to empirical observation and classification was evident in his biological studies during this period. He engaged in detailed examinations of plant and animal life, making significant contributions to the early understanding of natural history. His observations, while not always accurate by modern standards, laid the foundation for future developments in biology.

Unfortunately, only a fraction of Aristotle’s vast body of work has survived the centuries. The surviving works, often in the form of lecture notes or treatises, provide glimpses into the immense scope of his contributions. Whether exploring the nature of being in “Metaphysics,” discussing ethical virtues in “Nicomachean Ethics,” or laying the groundwork for systematic classification in “Categories,” Aristotle’s writings continue to be a source of inspiration and study in diverse fields.

Aristotle’s early life, marked by personal challenges, intellectual exploration, and the establishment of the Lyceum, serves as a crucial backdrop to understanding the foundations of his enduring legacy. His influence not only shaped the trajectory of Western philosophy but also left an indelible mark on fields ranging from ethics and politics to natural sciences—a testament to the enduring impact of a remarkable thinker whose journey began in the ancient city of Stagira.

Academic Career

Aristotle’s academic career, centered around his role as a philosopher, teacher, and founder of the Lyceum, represents a pivotal chapter in the history of intellectual inquiry. From his early education in Plato’s Academy to the establishment of his own school, Aristotle’s contributions to philosophy and various disciplines continue to resonate across centuries.

Aristotle’s academic journey began in Athens, where he joined Plato’s Academy around 367 BCE. This period of his life was marked by intensive philosophical engagement and intellectual exploration. Plato, the venerable philosopher and founder of the Academy, played a crucial role in shaping Aristotle’s early philosophical outlook. However, as Aristotle immersed himself in the Academy’s intellectual milieu, subtle differences in philosophical approach began to emerge between him and his mentor.

While Plato emphasized the world of abstract Forms as the ultimate reality, Aristotle’s penchant for empirical observation and a focus on the tangible world led to a departure from Plato’s idealism. This intellectual evolution laid the foundation for Aristotle’s distinctive philosophical system, which would later be articulated in his extensive writings.

After spending nearly two decades in the Academy, Aristotle’s academic trajectory took a turn following Plato’s death in 347 BCE. Despite being considered as a potential successor to lead the Academy, Aristotle’s departure from Athens was driven by both philosophical differences and, perhaps, a desire to forge his own intellectual path. This decision set the stage for the next phase of his academic journey.

Aristotle’s association with Alexander the Great played a pivotal role in shaping his academic career. As the tutor to the young prince, Aristotle had the opportunity to delve into a wide array of subjects, ranging from ethics and politics to natural sciences. The Macedonian court provided him with resources and access to knowledge that enriched his intellectual pursuits.

The tutoring relationship with Alexander not only contributed to Aristotle’s scholarly endeavors but also had broader implications for the dissemination of knowledge. The conquests of Alexander spread Greek influence across vast territories, fostering an environment where intellectual exchange flourished. Aristotle’s teachings and ideas, influenced by his experiences with Alexander, permeated through these regions, contributing to the synthesis of Greek philosophy with various cultural traditions.

Following Alexander’s conquests, Aristotle returned to Athens in 335 BCE. It was during this period that he founded his own school, the Lyceum, marking a significant milestone in his academic career. The Lyceum, situated in the outskirts of Athens, became a renowned center for learning and philosophical inquiry. Aristotle’s teaching style at the Lyceum was distinctive—he often walked while lecturing, leading to the school being referred to as the Peripatetic School.

Unlike the more exclusive nature of Plato’s Academy, the Lyceum had a more inclusive ethos. Aristotle welcomed a diverse group of students, and the school became a hub for intellectual exchange. The curriculum at the Lyceum covered a vast range of subjects, reflecting Aristotle’s interdisciplinary approach to knowledge. He lectured on ethics, politics, metaphysics, natural sciences, and more, underscoring the interconnectedness of various branches of inquiry.

The systematic and methodical nature of Aristotle’s teachings at the Lyceum is evident in his surviving works, often presented in the form of lecture notes or treatises. His approach to philosophy was characterized by a commitment to careful analysis, classification, and empirical observation. In “Nicomachean Ethics,” Aristotle delved into the nature of virtue and the pursuit of a morally fulfilling life. In “Politics,” he explored different forms of government and advocated for a balanced, mixed government.

A significant aspect of Aristotle’s academic legacy lies in his contributions to natural sciences. His biological studies, documented in works like “On the Parts of Animals” and “On the Generation of Animals,” demonstrated a keen interest in understanding the diversity of life through observation and classification. While some of his conclusions may not align with modern scientific understanding, his pioneering efforts laid the groundwork for future developments in biology.

Tragically, much of Aristotle’s extensive writings have been lost to time. However, the surviving works, combined with the influence of his ideas on subsequent generations of scholars, highlight the enduring impact of his academic career. The Lyceum, as an institution, played a crucial role in shaping Aristotle’s legacy and fostering intellectual inquiry long after his death.

Aristotle’s academic journey stands as a testament to the transformative power of education and the pursuit of knowledge. From his formative years in Plato’s Academy to the establishment of the Lyceum, Aristotle’s contributions continue to inspire scholars and thinkers across disciplines, marking him as one of history’s most influential figures in the realm of academia and philosophy.

Works and Writings

Aristotle’s prolific works and writings encompass a vast array of subjects, showcasing his profound impact on philosophy, ethics, politics, metaphysics, and the natural sciences. His systematic and analytical approach is evident in surviving texts, which include treatises, dialogues, and lecture notes. While some works have been lost to time, the extant corpus provides invaluable insights into Aristotle’s intellectual legacy.

One of Aristotle’s foundational works is “Nicomachean Ethics,” a treatise on moral philosophy. In this work, Aristotle explores the nature of virtue, ethics, and the pursuit of happiness. He introduces the concept of eudaimonia, often translated as “flourishing” or “the good life,” and argues that virtuous character is essential for achieving it. Aristotle identifies virtues as the mean between extremes, advocating for a balanced and moderate approach to ethical decision-making.

In “Politics,” Aristotle delves into the realm of political philosophy, examining different forms of government and their ethical implications. He categorizes governments based on whether they serve the common good or the interests of a ruling elite. Aristotle’s advocacy for a mixed government, combining elements of monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy, reflects his belief in achieving balance and avoiding the pitfalls associated with each form when taken to extremes.

Metaphysics, Aristotle’s magnum opus, explores the nature of being, existence, and reality. Divided into fourteen books, this work covers a wide range of topics, from substance and causality to potentiality and actuality. Aristotle introduces the concept of the unmoved mover, an eternal and uncaused entity that sets the cosmos in motion. His exploration of metaphysical principles has had a profound impact on Western philosophical thought, influencing thinkers from the medieval period to the present.

In “Physics,” Aristotle addresses the principles of natural philosophy, including concepts of motion, time, and space. He distinguishes between different types of causation, such as material, formal, efficient, and final causes, providing a comprehensive framework for understanding the natural world. While some of Aristotle’s scientific ideas have been superseded by later developments, his emphasis on systematic observation and classification laid the groundwork for the scientific method.

Aristotle’s logical treatises, including “Categories” and “On Interpretation,” form the basis of his contributions to formal logic. In “Categories,” he explores the classification of entities and introduces the notion of substance as a primary category. “On Interpretation” delves into language and propositions, discussing topics like truth, meaning, and the principles of contradiction and excluded middle. Aristotle’s logical works had a profound influence on medieval scholastic philosophers and continue to be studied in the field of logic.

The “Organon,” a collection of Aristotle’s logical treatises, includes works beyond “Categories” and “On Interpretation.” “Prior Analytics” introduces the theory of syllogism, a deductive reasoning system that became central to Aristotelian logic. “Posterior Analytics” explores scientific knowledge and demonstration, while “Topics” delves into dialectical reasoning and argumentation. The “Sophistical Refutations” addresses fallacies and deceptive reasoning. Together, these works form a comprehensive foundation for the study of logic.

Aristotle’s interest in rhetoric is evident in “Rhetoric,” where he examines persuasive communication. He identifies three modes of persuasion: ethos (character), pathos (emotion), and logos (reason). This work provides insights into the art of effective public speaking and persuasive discourse, contributing to the field of rhetoric.

In the realm of natural sciences, Aristotle’s biological works, such as “On the Parts of Animals” and “On the Generation of Animals,” demonstrate his keen observational skills. He classifies animals based on characteristics such as blood circulation and embryonic development, offering early insights into the diversity of living organisms. While some of his conclusions are outdated, Aristotle’s pioneering efforts laid the groundwork for the study of biology.

Aristotle’s literary style varies across his works. In dialogues like “Eudemian Ethics” and “On the Soul,” he engages in dialectical discussions, while more systematic treatises like “Nicomachean Ethics” and “Politics” present structured arguments. The surviving texts often appear as lecture notes, suggesting that Aristotle’s works were products of his teaching at the Lyceum.

Despite the richness of Aristotle’s extant corpus, the fate of some of his writings remains uncertain. The “Corpus Aristotelicum,” a collection of works attributed to Aristotle, includes both genuine and spurious texts. Scholars have debated the authenticity of certain works, such as the “Magnanimity” and “Eudaimonia,” leading to ongoing discussions about the extent of Aristotle’s lost writings.

In the centuries following Aristotle’s death, his works were preserved, studied, and commented upon by scholars in the Islamic world, contributing to the transmission of Greek philosophy. During the medieval period in Europe, Aristotle’s writings became central to scholastic philosophy, especially through the works of thinkers like Thomas Aquinas.

Aristotle’s enduring influence extends beyond philosophy into literature, science, and various academic disciplines. His systematic approach to inquiry, emphasis on empirical observation, and contributions to logic have left an indelible mark on the history of human thought. The ongoing study and interpretation of Aristotle’s works continue to shape contemporary discussions and provide a rich source of inspiration for scholars across the globe.

Philosophical Contributions

Aristotle’s philosophical contributions encompass a vast range of disciplines, shaping the course of Western thought and influencing scholars for centuries. His systematic approach to inquiry, emphasis on empirical observation, and insightful analyses laid the foundation for advancements in philosophy, ethics, metaphysics, politics, and natural sciences.

In metaphysics, Aristotle’s exploration of being, existence, and reality is encapsulated in his magnum opus, “Metaphysics.” He introduced the concept of substance, defining it as that which is independent and exists in its own right. Aristotle distinguished between potentiality and actuality, asserting that everything has both a potential state and an actual state. This conceptual framework became fundamental to understanding change and the nature of existence.