- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

Media Representations of Crime and Criminal Justice

Christopher Birkbeck, University of Salford

- Published: 02 September 2014

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

To date, criminologists have approached the media from a communications perspective that, directly or indirectly, treats them as a powerful social force. However, systematic research (conducted mainly outside but also within criminology) has failed to substantiate this image: the media may be an ubiquitous ingredient in daily life, but their influence is crucially mediated by social and psychological variables. Further progress in critically assessing the power of the media will depend on developments in media and communications theory rather than criminology. Meanwhile, criminologists could open up alternative lines of inquiry relating to the media’s quality of publicness and its location at the interface between revelation and concealment—an interface of considerable significance for crime and criminal justice. To do so would be to explore the media as a discourse, and materialization, of conventionality.

Introduction

Criminologists often criticize the media for a variety of sins, notably the emotiveness, distortion, and oversimplification that they bring to matters of crime and justice. This academic frustration is driven by the media’s social and technical accomplishments: their perceived capacity to create, reproduce, and deliver content in mind-boggling abundance and near instantaneity and their putative impacts on many aspects of social and cultural life. From this perspective, these apparently potent forms of communication subvert the work of criminology by purveying unrealistic images of crime and criminal justice and eschewing rational reflection about them.

Central to this critique are a conception of the media as a process of communication and an underlying imaginary drawn from physics. Messages are seen as profuse, ephemeral, but highly charged particles circulating in the social universe, with a potential to render some sort of change (in behavior, emotions, beliefs, or attitudes) in any individual or organization that they collide with. The predominant analytical framework is one of causal relations ( Greer and Reiner, 2012 ), within which media representations of crime and criminal justice are posited as both the outcome of societal and organizational processes and an influence on those who intersect with them. The communications perspective is shared with many other academic disciplines, most obviously media and communication studies. It was prefigured by social critics and the general public at least a century ago and—significantly—is still widely held today ( J. Anderson, 2008 ).

Notable for its absence has been any extended reflection on the merits and problems of adopting a communications perspective within criminology. For although this perspective has underpinned a burgeoning literature within the discipline ( Carrabine, 2008 ; Greer and Reiner, 2012 ; Jewkes, 2004 ; Mason, 2003 ; Surette, 2011 ), it appears to demand a vision of causality as a one-way process in which messages are merely an intermediate link between producers and consumers. From this viewpoint, a focus on the messages themselves will supposedly reveal important aspects of the production and consumption processes; or a focus on production will naturally look to its consequences for consumption. The problem, however, is that the messages produced are not necessarily the messages consumed, because the mere fact of production does not guarantee exposure or attention to content, and attention, if garnered, does not imply a singular reading. Criminologists have not been unaware of this, particularly those focusing on questions of meaning in media content (e.g., Carrabine, 2008 ; Rafter, 2007 ; Sparks, 1992 ), who have pointed out that texts are polysemic and may be interpreted in different ways by different consumers. Nevertheless, both the discipline in general and even these scholars in particular have not followed through on the implications of this claim, the former preferring to proceed as if the question of meaning can be ignored, and the latter opting to provide a presumed common reading of the texts that they consider. Both of these tactics create crucial weaknesses for their analyses. A better solution to the problem would be to treat messages as jointly determined by producers and consumers, but this would be to look much more closely at the process of communication and less at the particular images of crime and justice, at least for the time being. In other words, it would lead away from criminology into a more explicit engagement with communications theories and methods.

Some may see in this a welcome enrichment of approach through transdisciplinarity. But for those who are interested in remaining more firmly within the discipline there is an alternative perspective already hinted at by some of the studies on the production of media content. This perspective focuses on the media not as a process of communication but as a form of publicness and a key constituent of the contemporary public domain. Along with a host of other topics, matters of crime and criminal justice are made collectively visible by the media ( Thompson, 1995 , 2011 ), a process of some significance given that most instances of crime and many actions of criminal justice agencies seek some sort of secrecy. Interesting questions relate to the processes of revelation and concealment and to the media as the interface between them, questions partly touched on in existing studies but relegated to a relatively minor supporting role within the dominant communications perspective. Somewhat paradoxically, when looked at as a form of publicness, media representations of crime and justice offer a study in the production of conventionality.

The Challenges for a Communications Perspective

Difficulties in characterizing media representations of crime and justice.

Although scholarly interest in the media, crime, and justice has existed since at least the 1920s, researchers with a specialist focus on criminology did not begin to look at this topic until after the Second World War. The first task that they set for themselves, one that continues to serve as a staple ingredient in many contemporary projects, was to delineate the idiosyncratic renderings of crime and justice in the media. This could be done by comparing media content with the images of crime and justice furnished by systematic study (i.e., by criminology). For example, in perhaps the earliest study of this type, Davis (1952) compared changes in the amount of column inches devoted to crime in Colorado newspapers with changes in the volume of crimes recorded by the police. He found that the two were not associated.

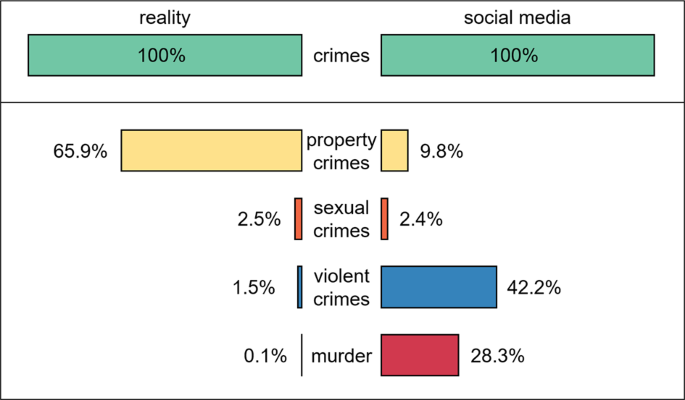

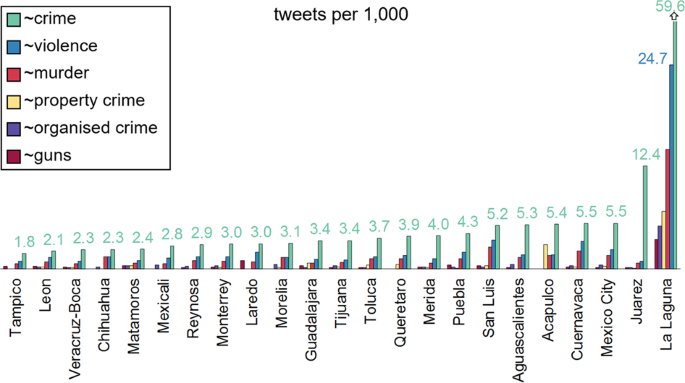

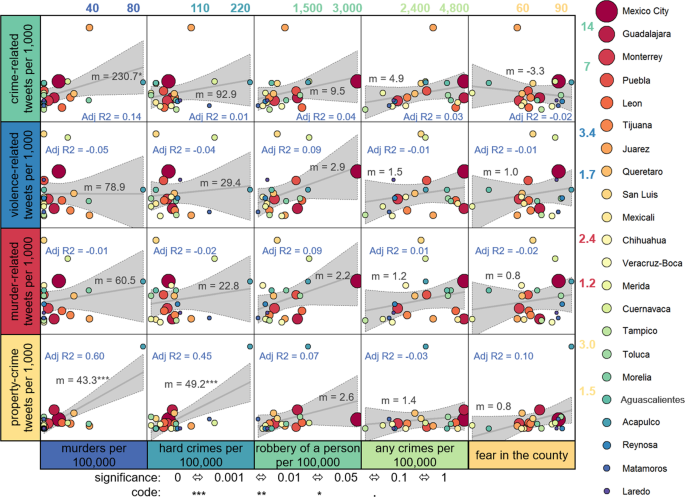

Much recent work has used content analysis to compare the proportional representation of different crime types, offenders, and criminal justice outcomes in the media with that found in official statistics. For example, in a study of items about crime published in British newspapers between 1945 and 1991, Reiner, Livingstone and Allen (2003 : 18) found that about two-thirds referred to violent or sex offenses, a picture that was “almost the obverse of [that given by] official statistics.” Similarly, Cheatwood (2010) found that fictional crime programs broadcast by radio in the United States between 1929 and 1962 dealt almost exclusively with murders, whereas murders never accounted for more than 0.5 percent of offenses known to the police. Both studies reported that the offenders featured in these media samples were older and of higher social status than the typical offender caught by the police. However, Pollak and Kubrin (2007) summarized more recent research that indicated that young violent offenders and offenders from ethnic minorities were overrepresented in news items compared to official statistics. Finally, Reiner, Livingstone, and Allen (2003) found that the clear-up rate for offenses reported in the news was above the general clear-up rate achieved by the police during the same period. These authors noted that media attention to the criminal justice system was largely confined to the police, as did Cheatwood. Surette (2011) has referred to the “Law of Opposites” and “Front End Loading” to designate the respective patterns of reporting.

Beyond simple comparisons like this, representational processes begin to look more complex. For example, Galeste, Fradella, and Vogel (2012 : 4) identified four “myths” about sex offenders—that they are “compulsive, homogenous, specialists and incapable of benefiting from treatment”—which, they claimed, are perpetuated by the media. Nevertheless, only 38 percent of the articles they examined contained at least one of these myths. Researchers have noted the penchant for certain news items to use strong condemnatory terms for offenders, such as “fiend” or “beast” for sex offenders ( Greer, 2003 ); yet this is to highlight the well-known difference between “tabloid” and “quality” news, which may be blurring ( Esser, 1999 ) but has not disappeared ( Peelo et al., 2004 ). An influential perspective for examining the “construction” of crime and justice has been that of “framing,” which studies particular configurations of problem definitions, causal interpretations, moral evaluations, and treatment recommendations ( Entman, 1993 : 52). However, frames are seen to originate in ideology, politics, culture, and science, rather than the media. The latter mainly serve as a means for communicating frames—for there are usually several frames in existence at any given time—and as a source of information for researchers interested in studying them. For example, Sasson (1995) identified five frames that characterize political, policy, media, and private “talk” about crime. This kind of variety in the media’s depictions of crime and criminal justice makes it very difficult to posit straightforward effects of the resulting content.

A particular problem is posed by the matter of interpretation: what does media content mean to the person who intersects with it? The construction of meaning may be partly set by the producer of the message or text, but it will also be shaped by the characteristics of those who attend to it: their cultural background, personal history, level of comprehension, and the context of reception ( McQuail, 2013 ). Nellis (2009 : 131), for example, observed that although The Shawshank Redemption may look like a “prison movie,” film critic Mark Kermode “plausibly argues … [that] … its overall appeal and popularity has had little to do with its specifically penal content.” Nevertheless, despite some sort of routine caveat of this nature, rather than explore different meanings criminologists have proceeded to provide their own extended reading of the text or content, implying that this is how it will be interpreted by others. For example, Rafter (2006 : 3) asserted that “crime films offer contradictory sorts of satisfaction: pride in our ability to think critically and root for the character who challenges authority …; and pride in our maturity for backing the restoration of moral order.” Whether these sorts of satisfaction arise among viewers has not been explored.

Criminologists link what is often claimed to be the media’s idiosyncratic renderings of crime and justice with two additional claims that would be significant if they were well supported. The first is that crime and criminal justice are prominent topics in the media (e.g., Beale, 2006 ). However, general inventories of media content show that these are merely two among many subjects in the news, such as the economy, civil rights, sport, and international affairs ( Quandt, 2008 ) and not the most frequent. In the realm of fiction, where classificatory tasks seem much more complicated ( Altman, 2003 ), films or shows about “crime” or “justice” sit alongside many others about “romance,” “comedy,” “science fiction,” and so on.

The second claim is that most people get their information about crime and justice from the media; at least, that is what they say when asked about it ( Marsh and Melville, 2009 ). This claim would seem unproblematic given that most criminological events cannot be witnessed directly, but it fails to give due consideration to other sources of information, such as that relayed by friends and acquaintances, or that which can be gained through personal experience as a protagonist or victim of crimes or, perhaps more important, lesser delicts of equal moral consequence to the individual (cf. Katz, 1987 ). More significantly, attention needs to be paid to the priority accorded to different sources of information and to the notion of “information” itself. What, exactly, is captured from the media? Perhaps people believe that the media are an important source of information, when something other than a single survey question used as a method of measurement might reveal different processes at work. Some of the limitations to survey research for measuring respondents’ contact with the media have been explored by Prior (2009) who found that many people overstate their viewing of TV news—sometimes quite considerably.

Related to this is a tendency among criminologists to assume that the samples of items compiled to demonstrate the “distorted” image of crime and justice will also have been seen, heard, or read by the public, but this is not necessarily the case ( Graber, 2004 ). Indeed, the only people likely to view and—more important—analyze these particular samples are the researchers themselves. Media and communications studies have long recognized that audiences are not passive recipients of messages (Livingstone and Das, 2103). Some people may never watch “slasher films,” and never want to; others may do everything possible to view them.

Seeking the Effects of Media Images of Crime and Justice

Research that directly seeks evidence of media effects represents a vast field of inquiry that has mainly been conducted outside of criminology, much of it in relation to topics that are of little or no interest to the discipline. However, matters relating to crime or criminal justice have often featured as questions of specific concern, or as case studies for broader conceptual and theoretical explorations. One prominent line of inquiry has involved the search for the effects of media content on violent and aggressive behavior ( J. Anderson, 2008 ). Another has looked at the effects of media on perceptions, beliefs, and attitudes relating to crime and justice (e.g., Holbrook and Hill, 2005 ). Some studies have used experimental methods, in which subjects were asked to read short texts or view video clips and were then canvassed for reactions or observed in their immediate behavior (e.g., Slater, Rouner, and Long, 2006 ). Other studies have asked samples of respondents about their recent engagement with the media, perceptions of crime, attitudes toward punishment, and associated matters (e.g., Goidel, Freeman, and Procopio, 2006 ). The focus of attention has been the individual, as reflected in the numerous theories of media effects—social learning, cognitive, reception, cultivation, agenda setting, and so on—proposed by psychologists, communications theorists, and others ( Bryant and Oliver, 2008 ). Criminologists undertaking empirical projects to detect effects have mainly focused their attention on fear of crime (e.g., Ditton et al., 2004 ) or punitiveness (e.g., Callanan, 2005 ), both of which link to the considerable interest within the discipline in the evolution of crime policy over the past 50 years and the well-documented shift from penal welfarism to populist punitiveness. In so doing, they have cited antecedent work from outside criminology, used similar research techniques, and obtained similar sorts of findings.

The cumulative results of this “individual effects” research, reported in literature reviews and meta-analyses, can be summarized as follows: variables measuring exposure or attention to the media are not always statistically significant; significance, when established, usually indicates association rather than causality; and the associations are comparatively weak. For example, J. Anderson (2008) reported that 70 years of research had shown correlations between media exposure and aggression ranging from .01 to .10. Similarly, C. Anderson and colleagues (2010) reported only small effects of violent video gaming on different dimensions of aggression. Morgan and Shanahan (2010 : 340) reported that a prior meta-analysis of more than two decades of cultivation research showed that television makes “a small but consistent contribution to viewers’ beliefs and perspectives.” Research has confirmed the ability of the media to influence people’s estimation of the most salient issues at any time—the so-called agenda-setting effect—including the issues of crime and criminal justice ( Uscinski, 2009 ). However, agenda setting can be weakened or eliminated by factors relating to personal experience or beliefs ( Graber, 2004 ). Translating these results into situated processes leads to what J. Anderson (2008 : 1272) called the “some/some/some” conditionals, as in “For some children under some conditions some television is harmful.”

For some commentators, these generally modest results are indicators that the search for effects is not a very fruitful enterprise ( Ferguson and Kilburn, 2010 ). For others, however, even small effects are worth documenting ( C. Anderson et al., 2010 ; Grabe and Drew, 2007 ). Given the multiple options for refining and varying the research strategy—changing samples, time frames, and measurement techniques; studying different variables relating to audiences, media types, genres, contents, and outcomes; testing different concepts and theories—there are endless possibilities for doing more of this kind of work in the search for more significant results.

Effects, however, have not only been researched and theorized in relation to the individual; they have also been discussed at the organizational level. Thus, and in relation to criminology’s subject matter, media content may affect the decisions made by the judiciary, bureaucrats, politicians, other media organizations, nongovernmental organizations, and so on. This has been one of the premises underlying studies of moral panics and scandals. For example, Cohen’s ([1972] 2003) initial work on a moral panic over youth violence in English seaside towns included extensive consideration, on the one hand, of the media treatment of the topic and, on the other, of official reactions to the “problem” (greater police control, harsher judicial treatment, and so on). Similarly, Greer and McLaughlin (2011 , 2012 ) described a “politics of outrage” that emerged in relation to the United Kingdom’s Metropolitan Police Service and that they linked to the resignation of one its commissioners and to complications in public order policing. The notion that the media have this kind of influence is also underwritten by the organizations themselves, most of which have a media strategy if not a media liaison office ( Mawby, 2010 ) and whose members sometimes cite the media as a factor that influences their decisions.

The methodological preference in this work is for case studies, but the latter have been limited by their reliance on the media as almost the sole data source. As colleagues working on individual effects would attest, any impact of the media on organizations cannot be demonstrated by focusing entirely on the media; additional determinants of decisions need to be examined. Researchers would need to observe for themselves what happens within organizations and assess the role of media alongside that of organizational resources, objectives, normative frameworks, the existence of institutional competitors, and the like. There is general agreement, both within criminology ( Surette, 2011 ) and outside of it ( Voltmer and Koch-Baumgartner, 2010 ), that this is a complex task and that, so far, the results have been equivocal: there are some processes or policy outcomes where significant media influence has been detected but many that seem completely impervious.

Despite these difficulties, criminologists doing empirical research on individual or organizational effects tend to be faithful to the communications canon. They argue that it would be premature to give up this line of inquiry ( Ditton et al., 2004 : 598) and often overstate the analytical significance of their findings (e.g., Callanan, 2005 ). What these media-centric studies reveal, however, is that the principal determinants of the phenomena under study lie elsewhere. For example, in their study of media usage and fear of crime Weitzer and Kubrin (2004) focused on four theories of media effects but hardly commented on the fact that in their results age, gender, race, and the local violent crime rate emerged as stronger predictors of fear. Another way of envisaging the peripheral role of the media in thinking about the causes of crime is to peruse any text on theories of criminal behavior, where discussion of the media is likely to make only a brief appearance and only in relation to social learning and anomie perspectives.

Several authors have correctly observed that the notion of effects needs to be critically assessed: people should not be seen as passive recipients of media messages but rather as individuals who intersect with these messages in different ways—purposefully, accidentally, attentively, distractedly, passionately, apathetically, and so on (e.g., Carrabine, 2008 ; Chiricos, Eschholz and Gertz, 1997 ; Sparks, 1992 ). And they have noted the importance of understanding how people make meaning out of the content they intersect with. For example, Rafter (2007) has suggested that the media provide individuals with a “tool kit” ( Swidler, 1986 ) of images and ideas about crime and justice that they use to develop their own discourse about these topics, a conception that grants much agency to the individual in the interpretation and subsequent use of media content. In making this kind of argument, these criminologists have drawn—explicitly or implicitly—on theories of audience and reception that have an established trajectory in media studies ( Livingstone and Das, 2013 ). But they have not studied audiences or reception, or provided inventories of interpretations, or typologies of media users (for a very limited exception see Chiricos, Eschholz, and Gertz, 1997 ). Instead, they have preferred to develop their own reading of media content and offer this as the likely reading among the audience. As suggestive as these readings might be, they can only be speculative: criminology as exegesis. To go beyond this demands sustained engagement with the concepts, theories, and methods of media and communications studies, for which matters of crime and justice simply become case material. There is no prima facie reason for thinking that the processes operating in the reception, interpretation, and use of media content on these topics are radically different to those operating in relation to, for example, the environment, politics, the economy, or fashion.

The Production of Media Representations of Crime and Justice

One of the stronger antidotes to the notion of passive media recipients lies in the concept of the market, a mechanism through which consumers express their preferences and cumulatively construct something like collective attention. From this perspective, it is the task of media organizations—which sit at the interface between demand and supply—to read market forces accurately and do their best to develop content that will attract sufficient attention. They may not always be successful in this: some content surprises because it garners so much attention; other content surprises because it garners so little. The most thorough examination of market forces in relation to crime and justice content was Hamilton’s (1998) , who argued that the presence or absence of violence in television programs is strongly determined by strategic attempts to attract particular audiences. Because the most frequent consumers of violence are viewers ages 18 to 34, channels and advertisers seek to target this group through programming schedules. More generally, crime and violence are thought to attract public attention and to have been used increasingly to maintain ratings ( Beale, 2006 ). In relation to news and reality TV shows, matters of crime and justice also have the added attraction of comparatively low production costs. Several criminologists and communications scholars have examined the journalistic practices which underlie the production of crime and justice news, including journalists’ routine reliance on specific sources for items of interest and the efforts of criminal justice agencies or stakeholders to influence and control what is reported ( Chermak and Weiss, 2005 ; Ericson, Baranek and Chan, 1987 , 1989 ; Schlesinger and Tumber, 1994 ; Silverman, 2012 ). They have demonstrated quite convincingly that the agendas of media organizations and sources frequently overlap and are consciously made to do so but that there are also inherent tensions between media objectives on one side and public relations on the other (see also Doyle, 2003 ). While media professionals and sources can usually maintain cooperative relationships in the generation of newsworthy items about crime—focusing on the immediate, the dramatic, the novel, the celebrity offender, and so on ( Jewkes, 2004 )—that relationship will rapidly become conflictive if the media turn a critical eye on agencies’ shortcomings.

Of course, newsworthiness can only be an explanation, and a superficial one at that, of the demand for factual content on crime and justice. Deeper explanations, which would also cover the demand for fictional content, require a different approach. Thus criminologists and others have gestured at individual and collective social processes that translate into the “demand” for certain kinds of media content on crime and justice. For example, Sparks (1992 : 120) speculated that crime fiction “presupposes an inherent tension between anxiety and reassurance and that this constitutes a significant source of its appeal to the viewer.” Echoing the earlier influential work of Hall and colleagues (1978) , he posited a “displacement” process by which widespread social anxieties about economic and social change (notably unemployment and immigration) were partly addressed and partly resolved through narratives depicting the overturn of disorder (see also Welsh, Fleming, and Dowler, 2011 ). Moving more toward the terrain of psychoanalysis, other researchers have written of voyeurism and the fascination with mediated crime and violence ( Carrabine, 2008 ; Jewkes, 2004 ), or of offenders as scapegoats “onto which society projects ‘its darkest fears and desires’ (Schober, 2007:135)” ( Kohm and Greenhill, 2011 : 196). Intriguing as these claims are, they have yet to be substantiated by systematic empirical research. More problematically, they seek to hold media portrayals of crime and justice in the largely contradictory position of simultaneously being a result of consumers’ demands and a determinant of their perceptions—a difficulty that might be resolved by arguing for a positive feedback spiral between the two but that has not so far been recognized or addressed. This sort of problem derives from the adherence to a communications perspective that ultimately privileges a focus on media representations as determinants of individuals’ images of crime and justice.

The Media as a Materialization of Publicness

Studies on the production of media content relating to crime and justice offer a useful starting point for developing an additional framework to the communications perspective. For example, Ericson, Baranek, and Chan (1989) looked at media-source relations in terms of openness and closure in the genesis of news. While criminal justice agencies “patrol the facts” ( Ericson, 1989 ) by attempting to establish particular dividing lines between what is revealed and what is concealed, journalists and others are often trying to move those divides. For Ericson and colleagues, unable to free themselves entirely from the framework of communication, the significance of this process lay mainly in its consequences for the inventory of news items that would be offered to consumers ( Ericson, Baranek, and Chan, 1991 ). But it is also significant for what it indicates about the tensions between social visibility and invisibility in relation to crime and justice. One set of tensions relates to that which is withheld from public view and another to that which is brought into the public domain. Both are founded on a widely held lay theory of media functioning. Both work to maintain a notional boundary to the public domain; both connect significantly with the dynamics of crime and criminal justice; and both support the production of conventionality in public life.

When legal or moral censures of behavior are powerful, those who think they will attract such censure usually work to keep the offense clandestine and its authorship anonymous. Few seek to publicize their own wrongdoing, except politically motivated actors, who often accompany their actions with discursive challenges to the prevailing normative climate—positioning themselves, for example, as “freedom fighters,” not terrorists. Video surveillance, now so widespread and an easy source of material for the news and entertainment media, is mainly ignored and sometimes avoided by those committing crimes in public places ( Phillips, 1999 ). For a long time some individuals—fascinated with deviance—have kept photos, home movies, or sound recordings of their crimes, and these have been joined more recently by “happy slappers” ( Chan et al., 2012 ) and others who record their clips on mobile phones ( Kenyon and Rookwood, 2010 ). But they have rarely sought to make these materials public, even if some of them have subsequently entered the public domain. The result, quite obviously, is that those who think that they are, or might be, engaged in wrongdoing will try to avoid public disclosure.

For media organizations, the undermining of secrecy can be a powerful source of news or infotainment. In its more confrontational mode, this process takes the form of revelations and seeks its justification in the idea of accountability. It is typically used against other organizations (in the criminal justice sector, particularly the police or prisons) or against white-collar or higher status offenders, and it often produces scandals. Information or allegations arising from these revelations may then be examined by police or prosecutors to determine whether legal action should be taken. While investigative reporting is obviously a prominent topic in journalism studies ( de Burgh, 2008 ), criminology has so far paid scant attention to it. Which sorts of crimes and delicts are investigated and why, how journalists gather and make sense of information, the roles played by whistle-blowers, and freedom-of-information requests are just some of the topics that are ripe for investigation.

In its lighter mode, designed for infotainment rather than accountability, the undermining of secrecy is much shallower, sometimes bordering on illusion. Here the media seek to get close to offending behavior but are hampered by the evasive tactics of their protagonists or by legal and ethical constraints on what can be revealed. It is not so difficult, of course, to find convicted offenders who will talk about what they have done rather than simply use the media to proclaim their innocence. However, their media performance is likely to center on justifications ( Sykes and Matza, 1957 ), excuses ( Scott and Lyman, 1968 ), or apologies ( Birkbeck, 2013 ) for their behavior, all of which represent discursive strategies for moral alignment with the public domain. When it comes to individuals who are supposedly involved in ongoing criminal activity as part of a gang or organized crime group, anonymity may be a condition of collaboration, and generalities the order of the day in what they say. Media organizations cannot learn about, witness, or generate criminal behavior in the course of their activities without an obligation to report it (even if they may not always do so), and consequently their domain of inquiry is quite limited. Thus the police and other spokespersons for criminal justice, bureaucrats in other branches of government, politicians, journalists, occasionally researchers, and victims and witnesses are the sources for news items ( Frost and Phillips, 2011 ; Thompson, Young, and Burns, 2000 ). Rarely included are those labeled as offenders ( Pollak and Kubrin, 2007 ). The interesting questions relate to presentational strategy: that which is revealed and that which is not by people who publicly acknowledge their engagement in crime. Those questions cannot be answered by focusing on the media appearance itself but only by comparing media revelations with revelations made to researchers who interact with these individuals under different conditions (although with similar ethical and legal obligations) and often for much longer periods of time (e.g., Miranda, 2003 ).

Thus where wrongdoers do not entirely evade public attention there seem to be many moral incentives that support the construction of accounts or apologies for their crimes. But even for the small group of rebels, terrorists, or others who would seek to defend their crimes or encourage others to join them there are legal and institutional barriers to getting a hearing. Media space is well policed, in order to exclude content that is considered undesirable. Schmid and De Graaf (1982 : 165), for example, cited rules within the CBS News organization that sought to avoid providing “an excessive platform for the terrorist/kidnapper”; while Miller (1984) reported a similar approach by the BBC to television coverage of the Provisional IRA in the United Kingdom. The object is to avoid incitement to crime—a crime itself—by publicizing nothing in the way of encouragement. In the United States, the First Amendment right to free speech has been curtailed by the courts when incitement to crime is argued to be in play ( Montz, 2002 ); in the United Kingdom, the Broadcasting Act of 1990 prohibited the dissemination of anything that “is likely to encourage or incite to crime or lead to disorder” ( Ofcom, 2013 ). Of course, this type of legislative control is based on a theory of noxious media effects, and its purview extends beyond the news to fictional portrayals of crime ( Montz, 2002 ). Criminology could do much by developing a critical perspective on the notion of incitement to crime and setting out the limitations to any simplistic view of media effects in this regard.

The right to free speech is also debated in relation to the media’s coverage of police investigations and criminal trials. In interviews with media representatives, witnesses may subtly change their accounts of events in order to comply with the interests of the news organization. Reports with information gathered by journalists about crimes, victims, or offenders may affect the perceptions and judgments of those involved in processing the case, particularly jurors (e.g., Spano, Groscup, and Penrod, 2011 ). Closure of proceedings, jury sequestering, and contempt of court are the measures typically used to control publicity in criminal cases, often aimed at limiting the perceived undesirable effects of the media (e.g., Conboy and Scott, 1996 ). Once again, there is scope for criminology to review the trends in, and characteristics of, this kind of control but from a theoretical rather than a normative perspective.

A concern for noxious effects also crystallizes in the controls on materials considered to be offensive to “good taste” and “decency” ( Shaw, 1999 ). Here the worry is less about the posterior effects of media content than about the reactions provoked at the moment of its reception: readers, listeners, or viewers may be shocked, offended, or repulsed ( Taylor, 1998 ). An associated concern is with the dignified treatment of those in the frame: too close an examination of grief, harm, or vulnerability may be felt to invade their privacy ( Fullerton and Patterson, 2006 ). Advocates, commentators, social critics, journalists, and legal scholars have examined the history, merits, and problems of this type of control (e.g., Couvares, 2006 ; Tait, 2009 ), but criminologists have not looked at censorship or control—whether external or self-imposed—of media content. Doing so would be less the addition of one more voice in the normative or historical debate about the appropriateness of particular media contents than an extended exploration of the contours of control: what material relating to crime or justice is felt to be inappropriate and why? Scholars in other disciplines (e.g., Campbell, 2004 ; Tait, 2008 ) have assembled some important observations relating to graphic portrayals of violence and death and have reflected on their uses, meanings, and moral significance, but these would need to be reexamined to understand the dynamics of revelation and concealment around crime. Campbell, for example, discussed the racist murder of James Byrd in Texas by three men who dragged him behind their truck for three miles. He noted the effects of this ordeal on the body of the victim—flesh worn down to the bone, ribs broken, head torn off, and so on—and the unsparing detail in the photographs of the deceased. These pictures were not carried by the news media, and the jurors found them “horrendous, and had to force themselves to look” (58). Criminologists could doubtless join other scholars here in considering whether these images should have been made public or what emotions they provoked in those who saw them, but a central criminological question—probably overlooked by other disciplines—concerns the understanding of concealment. Why are such graphic accounts of violence not made public? How does the boundary between revelation and concealment affect the meanings and censure brought to bear on these events? Within criminology, some purchase on this type of question can be gained through historical studies of the concealment of executions (e.g., Foucault, 1979 ; Lofland, 1975 ; Sarat and Schuster, 1995 ), but explanations—while very suggestive—are still quite speculative and topically focused. Their relevance would also have to be explored in relation to nonstate violence and to crimes that do not involve force but fraud or stealth.

Sociologist William Gamson (1988 : 162) once remarked that “There is some residue of [a lay theory of media effects] in all of us.” This lay theory accords great influence to the media because it equates publicness with collective attention and suggestibility. Systematic research, however, has failed to confirm the equation: in point of fact, media effects are mediated by social and psychological variables. Criminologists know this (through their reading of the extant literature) and have confirmed it for themselves (through their own studies of the media); nevertheless, they have largely continued to work within a communications perspective that is insinuated by the lay theory of media effects. They have thus been inattentive to an alternative conceptualization of the media as the construction of publicness and to the questions about the revelation and concealment of crime and criminal justice that thereby arise. Those questions lead in a number of different directions, offering additional lines of inquiry that look to be at least as productive as those currently pursued. They also imply a decentering of the media within the analytical frame, for revelation and concealment are inherent in every type of public domain, from street life to mass meetings. It is the visibility and accessibility of the media that makes them a convenient object for study.

Normative debates about “appropriate” media content on crime and justice reflect the importance accorded to the character of the public domain. In fact, the tensions relating to revelation and concealment spring from a desire to ensure that publicness is an exercise in conventionality, not deviance. This is reflected at the level of discourse, where the identities talked into being in the news are those of respectability; the community created in words and images is that of civil society; and the experience narrated is that of a melodramatic conflict between good and bad ( Birkbeck, 2013 ). Even fictional renderings of crime could be seen as rhetorics of conventionality: “Given the primacy of the hero, villains and their villainies may be relatively incidental” ( Sparks, 1992 : 147). And although the outcome of conflicts between good and bad may sometimes be ambiguous, the situation does not become more ambivalent; it simply becomes bleaker: “evil is ubiquitous, crime intractable, the criminal justice system impotent and moral redemption impossible” ( Rafter, 2007 : 409). Yet even a cursory glance at the media hints at the narrowness and superficiality of current convention. Surely there are better, more satisfying ways of discoursing on crime and justice.

Altman, R. ( 2003 ). “A Semantic/Syntactic Approach to Film Genre.” In Film Genre Reader III , edited by B.K. Grant , 27–41 (Austin: University of Texas Press).

Google Scholar

Google Preview

Anderson, C. , et al. ( 2010 ). “ Violent Video Game Effects on Aggression, Empathy, and Prosocial Behavior in Eastern and Western Countries: A Meta-Analytic Review. ” Psychological Bulletin 136(2): 151–173.

Anderson, J. ( 2008 ). “ The Production of Media Violence and Aggression Research: A Cultural Analysis. ” The American Behavioral Scientist 51(8): 1260–1279.

Beale, S. ( 2006 ). “ The News Media’s Influence on Criminal Justice Policy: How Market-Driven News Promotes Punitiveness. ” William & Mary Law Review 48(2): 397–482.

Birkbeck, C. ( 2013 ). Collective Morality and Crime in the Americas (New York: Routledge).

Bryant, J. , and Oliver, M. (eds.). ( 2008 ). Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum).

Callanan, V. ( 2005 ). Feeding the Fear of Crime: Crime-Related Media and Support for Three Strikes (New York: LFB Scholarly Publishing).

Campbell, D. ( 2004 ). “ Horrific Blindness: Images of Death in Contemporary Media. ” Journal for Cultural Research 8(1): 55–74.

Carrabine, E. ( 2008 ). Crime, Culture and the Media (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press).

Chan, S. , Khader, M. , Ang, J. , Tan, E. , Khoo, K. , and Chin, J. ( 2012 ). “ Understanding ‘Happy Slapping.’ ” International Journal of Police Science and Management 14(1): 42–57.

Cheatwood, D. ( 2010 ). “ Images of Crime and Justice in Early Commercial Radio—1932 to 1958. ” Criminal Justice Review 35(1): 32–51.

Chermak, S. , and Weiss, A. ( 2005 ). “ Maintaining Legitimacy Using External Communication Strategies: An Analysis of Police-Media Relations. ” Journal of Criminal Justice 33(5): 501–512.

Chiricos, T. , Eschholz, S. , and Gertz, M. ( 1997 ). “ Crime, News and Fear of Crime: Toward an Identification of Audience Effects. ” Social Problems 44: 342–357.

Cohen, S. ([ 1972 ] 2003). Folk Devils and Moral Panics (New York: Routledge).

Conboy, M. , and Scott, A. ( 1996 ). “ Tipping the Scales of Justice: An Attempt to Balance the Right to a Fair Trial with the Right to Free Speech. ” Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development 11(3): 775–803.

Couvares, F.G. (ed.). ( 2006 ). Movie Censorship and American Culture (Boston: University of Massachusetts Press).

Davis, F.J. ( 1952 ). “ Crime in Colorado Newspapers. ” American Journal of Sociology 57(4): 325–330.

de Burgh, H. (ed.). ( 2008 ). Investigative Journalism (New York: Routledge).

Ditton, J. , Chadee, D. , Farrall, S. , Gilchrist, E. , and Bannister, J. ( 2004 ). “ From Imitation to Intimidation: A Note on the Curious and Changing Relationship between the Media, Crime and Fear of Crime. ” British Journal of Criminology 44(4): 595–610.

Doyle, A. ( 2003 ). Arresting Images: Crime and Policing in Front of the Television Camera (Toronto: University of Toronto Press).

Entman, R. ( 1993 ). “ Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm. ” Journal of Communication 43(4): 51–58.

Ericson, R. ( 1989 ). “ Patrolling the Facts: Secrecy and Publicity in Police Work. ” The British Journal of Sociology 40(2): 205–226.

Ericson, R. , Baranek, P. , and Chan, J. ( 1987 ). Visualizing Deviance: A Study of News Organization (Toronto: University of Toronto Press).

Ericson, R. , Baranek, P. , and Chan, J. ( 1989 ). Negotiating Control: A Study of News Sources (Toronto: University of Toronto Press).

Ericson, R. , Baranek, P. , and Chan, J. ( 1991 ). Representing Order: Crime, Law, and Justice in the News Media (Toronto: University of Toronto Press).

Esser, F. ( 1999 ). “ ‘Tabloidization’ of News : A Comparative Analysis of Anglo-American and German Press Journalism,” European Journal of Communication 14(3): 291–324.

Ferguson, C. , and Kilburn, J. ( 2010 ). “ Much Ado about Nothing: The Misestimation and Overinterpretation of Violent Video Game Effects in Eastern and Western Nations: Comment on Anderson et al. (2010). ” Psychological Bulletin 136(2): 174–178.

Foucault, M. ( 1979 ). Discipline and Punish (New York: Vintage).

Frost, N. , and Phillips, N. ( 2011 ). “ Talking Heads: Crime Reporting and Cable News. ” Justice Quarterly 28(1): 97–112.

Fullerton, R. , and Patterson, M. ( 2006 ). “ Murder in Our Midst: Expanding Coverage to Include Care and Responsibility. ” Journal of Mass Media Ethics 21(4): 304–321.

Galeste, M. , Fradella, H. , and Vogel, B. ( 2012 ). “ Sex Offender Myths in Print Media: Separating Fact from Fiction in U.S. Newspapers. ” Western Criminology Review 13(2):4–24.

Gamson, W. ( 1988 ). “ The 1987 Distinguished Lecture: A Constructionist Approach to Mass Media and Public Opinion. ” Symbolic Interaction 11(2): 161–174.

Goidel, R. , Freeman, C. , and Procopio, S. ( 2006 ). “ The Impact of Television Viewing on Perceptions of Juvenile Crime. ” Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media 50(1): 119–139.

Grabe, M. , and Drew, D. ( 2007 ). “ Crime Cultivations: Comparisons across Media Genres and Channels. ” Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media 51(1): 147–171.

Graber, D. ( 2004 ). “ Mediated Politics and Citizenship in the Twenty-First Century. ” Annual Review of Psychology 55:545–571.

Greer, C. ( 2003 ). Sex Crime and the Media: Sex Offending and the Press in a Divided Society , (Cullompton, UK: Willan).

Greer, C. , and McLaughlin, E. ( 2011 ). “‘Trial by Media’: Policing, the 24-7 News Mediasphere and the ‘Politics of Outrage. ’” Theoretical Criminology 15(1): 23–46.

Greer, C. , and McLaughlin, E. ( 2012 ). “ ‘This Is Not Justice’: Ian Tomlinson, Institutional Failure and the Press Politics of Outrage. ” British Journal of Criminology 52:274–293.

Greer, C. , and Reiner, R. ( 2012 ). “Mediated Mayhem: Media, Crime and Criminal Justice.” In The Oxford Handbook of Criminology , edited by M. Maguire , R. Morgan , and R. Reiner , 245–278 (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Hall, S. , Critcher, C. , Jefferson, T. , Clarke, J. , and Roberts, B. ( 1978 ). Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State, and Law and Order (London: Macmillan).

Hamilton, J.T. ( 1998 ). Channeling Violence: The Economic Market for Violent Television Programming (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press).

Holbrook, R. , and Hill, T. ( 2005 ). “ Agenda-Setting and Priming in Prime Time Television: Crime Drama as Political Cues. ” Political Communication 22(3): 277–295.

Jewkes, Y. ( 2004 ). Media and Crime (Newbury Park, CA: SAGE).

Katz, J. ( 1987 ). “ What Makes Crime ‘News’? ” Media, Culture and Society 9:47–75.

Kenyon, J. , and Rookwood, J. ( 2010 ). “ ‘One Eye in Toxteth, One Eye in Croxteth’—Examining Youth Perspectives of Racist and Anti-Social Behaviour, Identity and the Value of Sport as an Integrative Enclave in Liverpool. ” International Journal of Arts and Sciences 3(8): 496–519.

Kohm, S.A. , and Greenhill, P. ( 2011 ). “ Pedophile Films as Popular Culture: A Problem of Justice? Theoretical Criminology 15(2): 195–215.

Livingstone, S. , and Das, R. ( 2013 ). “The End of Audiences? Theoretical Echoes of Reception Amid the Uncertainties of Use.” In A Companion to Media Dynamics , edited by J. Hartley , J. Burgess , and A. Bruns , 104–121 (Chichester, UK: Blackwell).

Lofland, J. ( 1975 ). “ Open and Concealed Dramaturgic Strategies: The Case of the State Execution. ” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 4(3): 272–295.

Marsh, I. , and Melville, G. ( 2009 ). Crime, Justice and the Media (New York: Routledge).

Mason, P. (ed.). ( 2003 ). Criminal Visions: Media Representations of Crime and Justice (Cullompton, UK: Willan).

Mawby, R. ( 2010 ). “ Policing Corporate Communications, Crime Reporting and the Shaping of Policing News. ” Policing and Society 20(1): 124–139.

McQuail, D. ( 2013 ). “ The Media Audience: A Brief Biography—Stages of Growth or Paradigm Change? ” The Communication Review 16:9–20.

Miller, D. ( 1984 ). “ The Use and Abuse of Political Violence. ” Political Studies 32:401–419.

Miranda, M. ( 2003 ). Homegirls in the Public Sphere (Austin: University of Texas Press).

Montz, V. ( 2002 ). “ Recent Incitement Claims against Publishers and Filmmakers: Restraints on First Amendment Rights or Proper Limits on Violent Speech? ” Virginia Sports and Entertainment Law Journal 1(2): 171–210.

Morgan, M. , and Shanahan, J. ( 2010 ). “ The State of Cultivation. ” Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media 54(2): 337–355.

Nellis, M. ( 2009 ). “ The Aesthetics of Redemption: Released Prisoners in American Film and Literature. ” Theoretical Criminology 13(1): 129–146.

Ofcom ( 2013 ). Programme Code, Section 1: Family Viewing Policy, Offence to Good Taste and Decency, Portrayal of Violence and Respect for Human Dignity (London, UK: Ofcom). http://www.ofcom.org.uk/static/archive/itc/itc_publications/codes_guidance/programme_code/section_1.asp.html, accessed July 20, 2013.

Peelo, M. et al. ( 2004 ). “ Newspaper Reporting and the Public Construction of Homicide. ” British Journal of Criminology 44:256–275.

Phillips, C. ( 1999 ). “ A Review of CCTV Evaluations: Crime Reduction Effects and Attitudes Towards its Use. ” Crime Prevention Studies 10:123–155.

Pollak, J. , and Kubrin, C. ( 2007 ). “ Crime in the News: How Crimes, Offenders and Victims Are Portrayed by the Media. ” Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture 14(1): 59–83.

Prior, M. ( 2009 ). “ Improving Media Effects Research through Better Measurement of Media Exposure. ” The Journal of Politics 71(3): 893–908.

Quandt, T. ( 2008 ). “ (No) News on the World Wide Web? A Comparative Content Analysis of Online News in Europe and the United States. ” Journalism Studies 9(5): 717–738.

Rafter, N. ( 2006 ). Shots in the Mirror: Crime Films and Society (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Rafter, N. ( 2007 ). “ Crime, Film and Criminology: Recent Sex-Crime Movies. ” Theoretical Criminology 11(3): 403–420.

Reiner, R. , Livingstone, S. , and Allen, J. ( 2003 ). “From Law and Order to Lynch Mobs: Crime News since the Second World War.” In Criminal Visions: Media Representations of Crime and Justice , edited by P. Mason , 13–32 (Cullompton, UK: Willan).

Sarat, A. , and Schuster, A. ( 1995 ). “ To See or Not to See: Television, Capital Punishment, and Law’s Violence. ” Yale Journal of Law and the Humanities 7(2): 397–432.

Sasson, T. ( 1995 ). Crime Talk: How Citizens Construct a Social Problem (New York: Aldine de Gruyter).

Schlesinger, P. , and Tumber, H. ( 1994 ). Reporting Crime: The Media Politics of Criminal Justice (Oxford: Clarendon Press).

Schmid, A.P. , and De Graaf, J. ( 1982 ). Violence as Communication: Insurgent Terrorism and the Western News Media (Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE).

Scott, M. , and Lyman, S. ( 1968 ). “ Accounts. ” American Sociological Review 33(1): 46–62.

Shaw, C. ( 1999 ). Deciding What We Watch: Taste, Decency and Media Ethics in the UK and the USA (New York: Oxford University Press).

Silverman, J. ( 2012 ). Crime, Policy and the Media: The Shaping of Criminal Justice 1989–2010 (London: Routledge).

Slater, M. , Rouner, D. , and Long, M. ( 2006 ). “ Television Dramas and Support for Controversial Public Policies: Effects and Mechanisms. ” Journal of Communication 56:235–252.

Spano, L. , Groscup, J. , and Penrod, S. ( 2011 ). “Pretrial Publicity and the Jury: Research and Methods.” In Handbook of Trial Consulting , edited by R. Weiner and B. Bornstein , 217–244 (New York: Springer).

Sparks, R. ( 1992 ). Television and the Drama of Crime: Moral Tales and the Place of Crime in Public Life (Philadelphia: Open University Press).

Surette, R. ( 2011 ). Media, Crime and Criminal Justice (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth).

Swidler, A. ( 1986 ). “ Culture in Action: Symbols and Strategies. ” American Sociological Review 51(2): 273–286.

Sykes, G. , and Matza, D. ( 1957 ). “ Techniques of Neutralization: A Theory of Delinquency. ” American Sociological Review 22(6): 664–670.

Tait, S. ( 2008 ). “ Pornographies of Violence? Internet Spectatorship on Body Horror. ” Critical Studies in Media Communication 25(1): 91–111.

Tait, S. ( 2009 ). “ Visualising Technologies and the Ethics and Aesthetics of Screening Death. ” Science as Culture 18(3): 333–353.

Taylor, J. ( 1998 ). Body Horror: Photojournalism, Catastrophe and War (New York: New York University Press).

Thompson, C. , Young, R. , and Burns, R. ( 2000 ). “ Representing Gangs in the News: Media Constructions of Criminal Gangs. ” Sociological Spectrum 20:409–432.

Thompson, J. ( 1995 ). The Media and Modernity: A Social Theory of the Media (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press).

Thompson, J. ( 2011 ). “ Shifting Boundaries of Public and Private Life. ” Theory Culture and Society 28(4): 49–70.

Uscinski, J.E. ( 2009 ). “ When Does the Public’s Issue Agenda Affect the Media’s Issue Agenda (and Vice Versa)? Developing a Framework for Media-Public Influence. ” Social Science Quarterly 90(4): 796–815.

Voltmer, K. , and Koch-Baumgarten, S. ( 2010 ). “Introduction: Mass Media and Public Policy—Is There a Link?” In Public Policy and Mass Media: The Interplay of Mass Communication and Political Decision Making, edited by S. Koch-Baumgarten and K. Voltmer , 1–13 (London: Routledge).

Weitzer, R. , and Kubrin, C. ( 2004 ). “ Breaking News: How Local News and Real-World Conditions Affect Fear of Crime. ” Justice Quarterly 21(3): 497–520.

Welsh, A. , Fleming, T. , and Dowler, K. ( 2011 ). “ Constructing Crime and Justice on Film: Meaning and Message in Cinema. ” Contemporary Justice Review: Issues in Criminal, Social, and Restorative Justice 14(4): 457–476.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press