- TOP CATEGORIES

- AS and A Level

- University Degree

- International Baccalaureate

- Uncategorised

- 5 Star Essays

- Study Tools

- Study Guides

- Meet the Team

Extended Essay - The Role of a UN-Secretary General to Achieve World Peace: The Endeavor of U Thant in Handling the Cuban Missile Crisis

Candidate Number: 006048004

Topic: The Role of a UN Secretary-General to Achieve World Peace: The Endeavour of U Thant in handling the Cuban Missile Crisis

Question: To what extent did U Thant play a vital role as Secretary-General of the United Nations, maintaining his neutral position, in keeping the peace and preventing a Nuclear Warfare by Disentangling the US-Soviet Conflict in the Caribbean Area in 1962?

Name: Zwe Kyaw Zwa

Candidate Number: 006048-004

Centre Number: 6048

Subject: History

Extended Essay Supervisor: Ms. Sandar Chen Date: 16/9/2012

Word Count: 3975

Abstract: 280

This extended essay examines the question: To what extent did U Thant play a vital role as Secretary-General of the United Nations, maintaining his neutral position, in keeping the peace and preventing a nuclear warfare by disentangling the US-Soviet Conflict in the Caribbean area in 1962? My thesis examines the historical investigation of the US naval quarantine of the Soviet shipment of nuclear warheads to Cuba, the confrontational conversations between the conflicting governments and U Thant’s unbiased negotiation for compromised solution for world peace. Along with the withdrawal of the Soviet warships and bombers, and the disassembling of nuclear weapons in Cuba, the crisis ends with US’s pledge of not invading Cuba.

The scope of the essay is restricted only to the negotiations between the state leaders of the conflicting nations, John F. Kennedy, Nikita Khrushchev and Fidel Castro, and the UN Secretary-General U Thant. Also, the essay does not explore the historical details of the background of the crisis but focuses mainly on U Thant’s compromised solution destined to peace during the Cuban missile crisis. In order to examine the research question, secondary sources relating to U Thant’s position in the crisis written by both foreign and Burmese authors, including the Secretary-General himself, are used.

The investigation undertaken leads to the conclusion that U Thant’s attempt to solve the crisis was more significant rather than the role played by Kennedy, Khrushchev and Castro. It can also be learnt from this historical event that a peaceful, impartial solution to the crisis is better than a confrontation by warfare. Therefore, the third Secretary-General’s involvement in settling the Cuban missile crisis as a neutral mediator for peace negotiations is of vital significance.

- Abstract………………………………………………………………..2

- Introduction…………………………………………………………....4

- Direct Confrontation of US and USSR negotiated by U Thant for Peace in the Cuban Missile Crisis

- The Threat of a Nuclear War……………………………….5

- First Phase: The Naval Quarantine ………...........................6

- Second Phase: Negotiation Peak…………………………...9

- Third Phase: Mission to Cuba……………………………..12

- Resolution………………………………………………….15

- Conclusion............................................... …………………………....16

- Bibliography………………………………………………………….18

- Appendices…………………………………………………………...20

- Introduction

During U Thant’s tenure as the third Secretary-General of the United Nations, he was instrumental in solving numerous peace-threatening crises such as the Cuban missile crisis in the Caribbean area (1962), the formation of independent Malaysia (1963), the Congo Civil War (1960-64), the Cyprus crisis (1963-64) and the emergence of Bangladesh (1971). Out of these, this extended essay analyses the Cuban missile crisis in details in order to highlight U Thant’s peace-keeping role in saving the world on a brink of nuclear war.

U Thant’s neutral position as a mediator between the nuclear superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union, to achieve world peace has been emphasized. Among the most difficult problems he tackled, this crisis seems to be the most prominent event in which U Thant fulfilled his responsibility as a Secretary-General to shun war and seek peace in times even when he was presented with the most challenging obstacles and dilemmas. The choice of compromised diplomacy by U Thant rather than military confrontation has prevented the devastating effects of warfare such as a massive loss of lives, economic failure, starvation and famine, as well as health problems including the social impacts on the victims of war.

Despite U Thant’s contribution in solving the missile crisis, his efforts have not been recognized over time, when books published on the crisis emphasize only on President John F. Kennedy, leaving the Secretary-General’s role out of the conflict. Traditionalists believed that the victor of the crisis was America according to the popular belief that when two world powers went eye-ball to eye-ball, “the other guy blinked.” On the other hand, revisionists assumed that Kennedy had consented to Khrushchev’s proposal for political gain. However, no one called attention to U Thant’s vital role as a neutral mediator and peace negotiator in the crisis. Therefore, the purpose of this extended essay is to remind the world of U Thant’s participation as a central figure in solving the major conflict between two nuclear superpowers which would certainly have led to a catastrophe.

- Direct Confrontation of US and USSR Negotiated by U Thant for Peace in the Cuban Missile Crisis

- The Threat of a Nuclear War

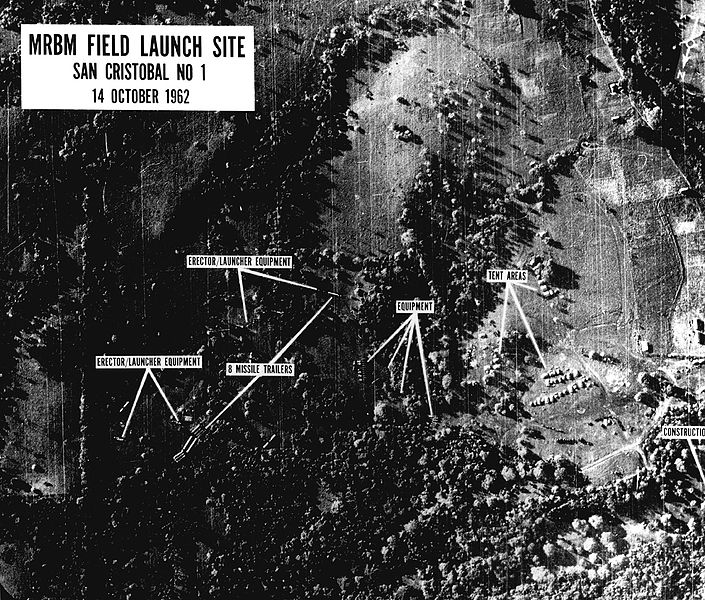

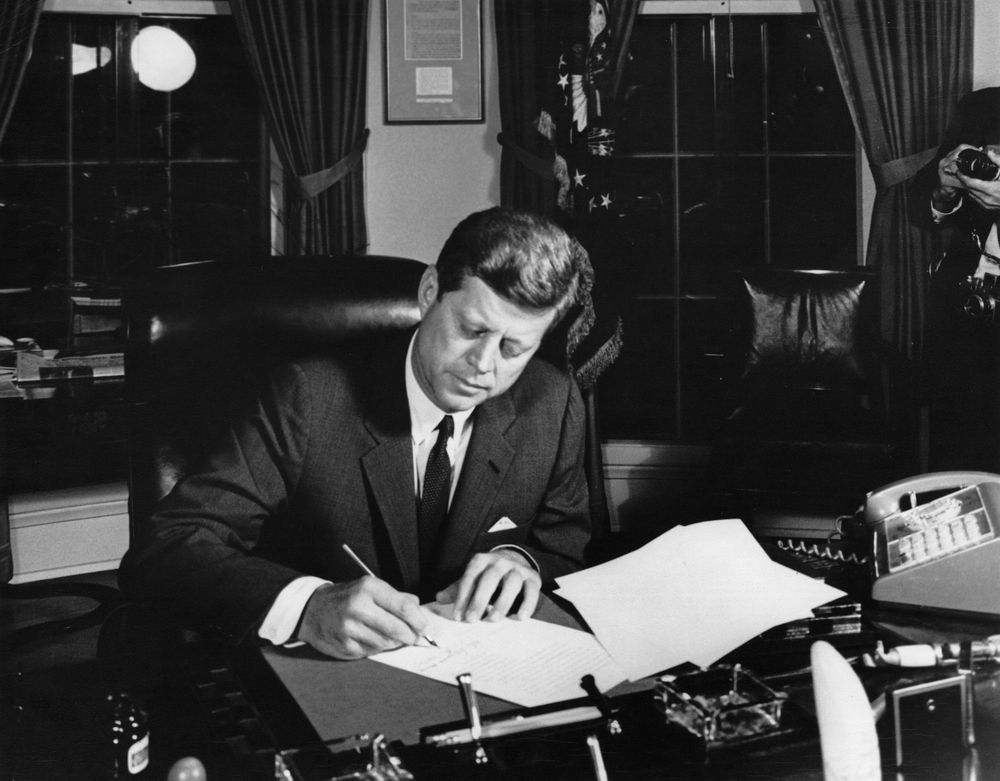

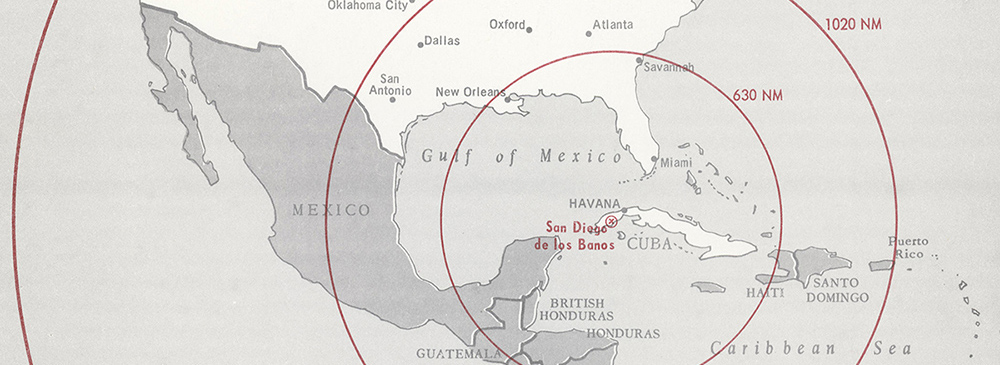

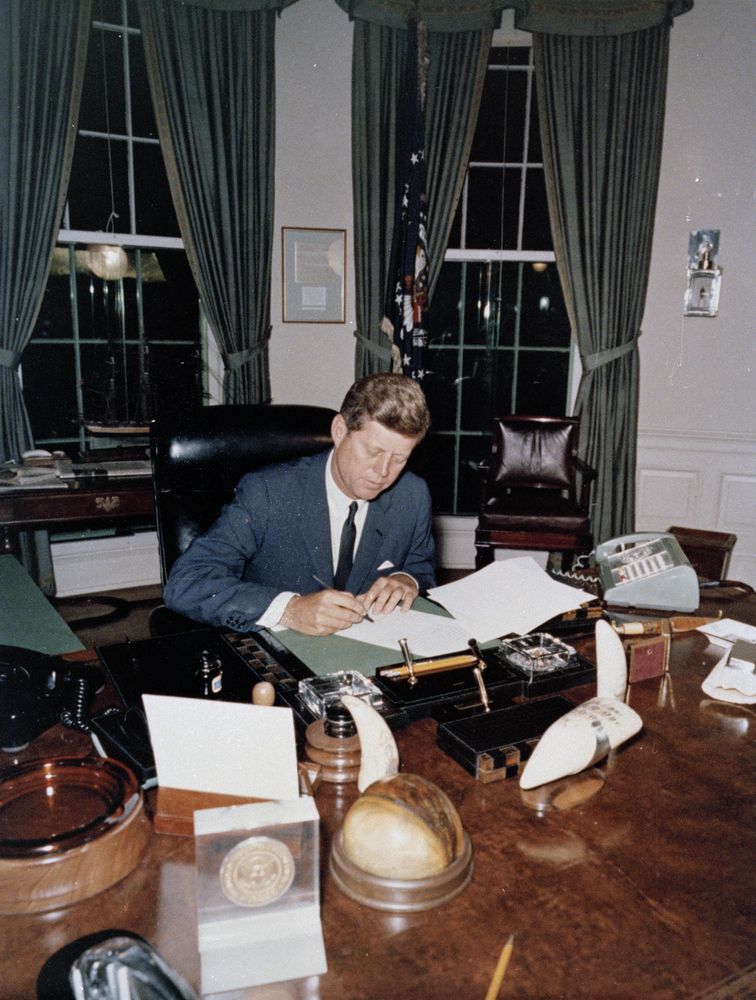

On 22 nd October 1962, the United States president, John F. Kennedy, made one of 20th century's most memorable presidential speeches. Kennedy told the world of the Soviet Union’s secret plans to build bases in Cuba, capable of launching nuclear missiles which had a range of over 2,000 miles. His announcement to begin a '500 mile naval and air quarantine' on 24th October on all military cargo under shipment to Cuba alarmed the world. He also requested the United Nations to intervene in order to de-escalate and resolve the nuclear standoff between the USSR and the USA.

Kennedy’s speech could be assumed illegitimate as the United States had no right to interfere in the Soviet’s shipment to Cuba which was travelling on the International route. The US and the USSR could have consulted with the UN in order to solve to the crisis without notifying the world, which had made the case much more critical. On the other hand, the urgency of the crisis had made the United Nations’ involvement even more crucial.

- First Phase: The Naval Quarantine

Soon after the United States had called upon an emergency meeting of the Security Council, U Thant, the United Nations' Secretary-General, received further requests from the Soviet Union and Cuba to solve the predicament, stating that the action of the US was breaching the UN Charter and international law, and that Cuba had been forced to prepare to defend itself against “American aggression,” respectively. Apparently, each of the concerned nations desired the United Nations to fulfill its demand; the US wished the UN to withdraw the shipment of offensive weapons to Cuba while the USSR demanded the UN to lift the naval blockade on Cuba, leading to the fact that it considered the UN to be nothing more than a mediating organization. Therefore, the peace desired by these nations was of bias while the duty of a Secretary-General was to seek a consensual peace.

During a tense week of serious discussion, despite the US’s anticipation of the UN’s role in the crisis, the Secretary-General himself was not expected to play a vital part. Furthermore, the United States viewed the UN only as an assembly in which it would gain approval of the world view and an organization providing eyewitness to the withdrawal of Soviet weapons from Cuba. However, the Americans’ underestimation on U Thant was proved wrong when he soon displayed the extent of his mediation and intervention in the crisis.

Advised by the forty-five delegations of non-aligned countries, U Thant sent two identical appealing messages on 24 th October directly to Premier Nikita Khrushchev of the Soviet Union and President John F. Kennedy of the United States. The entreaty involved voluntary deferment of all quarantine measures and arms shipments to Cuba for three weeks. These written messages were the first evidence of U Thant’s peaceful, unbiased negotiation.

This is a preview of the whole essay

The Americans’ initially responded to U Thant’s message with dissatisfaction. Since his message did not request the deconstruction of the Cuban missile sites and removal of the weapons, the US dreaded that it would have to consent to remove the blockade without a parallel action to any military activity in Cuba. The US ambassador Adlai Stevenson even asked U Thant to delay sending the message for a day. Furthermore, U Thant was requested to restrain mentioning only “vague references to verification” and without references to the Cuban missile sites by Secretary of State Dean Rusk in the speech which he had decided to deliver at the Security Council meeting the same day. All the more, the president himself ordered Stevenson to force U Thant to postpone his speech. To all these demands, U Thant refused since he might have perceived fruitful consequences and therefore, demonstrated his capability to make independent decisions as a Secretary-General.

On 24th October, at the Security Council meeting, U Thant proclaimed the contents of the two messages as well as the possible negotiation through a common ground; that, with the US’s assurance of not invading Cuba, all weaponry would be removed. He further expressed his opinion that “moderation, self-restraint and good sense…above the anger of the moment or the pride of nations…will prevail over all other considerations.” This statement reflected his understanding of overcoming war with negotiation and peace.

U Thant’s public statement was strongly criticized by the Soviet Union ambassador Valery Zorin, for not vigorously disapproving the US’s quarantine on Cuba. Irritated by his persistent censure, U Thant suggested to Zorin to make this claim at the Security Council meeting, which he did so. Taking Zorin as an example, it could be possible that most Russians would have initially thought his statement was unsatisfying. Yet, U Thant’s instruction to Zorin further proved that a Secretary-General stood as a neutral independent figure. Moreover, U Thant sent a message to Moscow explicating the efforts he had undertaken to be unbiased and requested the explanation of the objection. Two days later, Khrushchev notified the Secretary-General that Vasily Kuznetsov, First Deputy Foreign Minister, would arrive to head the Soviet Delegation. Here, U Thant displayed the authority of a Secretary-General, going to such an extent as to relegate Zorin in order to solve the issues with a more impartial negotiator.

In the evening, on 25 th October, U Thant received a cable from Khrushchev with a positive response to his appeal. It read: “I understand your concern…I agree to your proposal, which is in the interest of peace.” Khrushchev’s reply was a critical evidence of U Thant’s success in his very first initiative. The New York Times praised his achievement in its article: “Thant Bids U.S. and Russia Desists 2 Weeks.” Ambassador Stevenson expressed his admiration for U Thant’s accomplishment by claiming that it was “the indispensable first step in the peaceful resolution of the Cuba crisis.”

- Second Phase: Negotiation Peak

U Thant’s peaceful agreement improved the crisis at sea when Khrushchev ordered several of his ships to withdraw. However, “freighters and tankers,” including a Soviet tanker (Bucharest), were still approaching the interception area where a war could erupt upon intervention by the US navy. The superpowers were still challenging each others’ rights. Khrushchev had sent a cable to Kennedy saying, “We will not simply be bystanders with regard to piratical acts by American ships on high seas…to protect our rights.” The solemnity of the crisis had yet to pass.

Right then, the US requested U Thant to make another appeal to the Soviet even though it had not agreed to his first message yet. Kennedy said to Stevenson, “See if U Thant on his own responsibility will ask Mr. Khrushchev not to send his ships pending modality.” Seeing an opportunity, U Thant agreed to include the contents, which he contemplated as bases of achieving peace, in his message:

- Concern over an imminent war between the confronting nations

- Fear of previous discussions turn into futility

- Plea to delay the Soviet shipments to Cuba

- Assurance of the US withholding the attack to advancing Soviet ships

On 25 th October, U Thant sent this cable to Khrushchev and at the same time, sent another to Kennedy, advising him to strain his forces from directly antagonizing the Soviet navy. In this way, being an unbiased Secretary-General, U Thant had verified his action by appealing to both nations instead of only the USSR. Moreover, he had anticipated that Khrushchev would be able to avoid embarrassment, giving him an honorable way out without displaying weakness by momentarily stopping the advancement for peaceful negotiations.

All this time, Kennedy was convinced that U Thant would bring light to the problem; “U Thant is supposedly arranging for the Russians to stay out. So we have to let some hours to by…” Therefore, he immediately agreed to U Thant’s second appeal. This showed that the US had acknowledged U Thant’s efforts by having high expectations from him.

The Secretary-General once again made a feat when both leaders replied in agreement to his appeal. Once again, U Thant’s achievement made the front page on the New York Times: “Moscow Agree to Avoid Blockade Zones after New Plea from Thant on Talks.”

The matter then progressed to uprooting the offensive arms in Cuba. With the standstill of the Soviet ships as well as the US’s assurance of non-violence movement, the US delegation, led by John J. McCloy, and the Soviet delegation, led by Vasily Kuznetsov, along with U Thant himself, discussed over the issue of dismantling the Cuban missiles. The Security Council meetings from 25 th October to 28 th October were probably the most significant ones in bringing peace to the crisis.

During these meetings, U Thant proposed a crucial offer, a ‘non-invasive pledge formula,’ which would become the backbone of the resolution. A few weeks ago, on 8 th October, Cuban President Osvaldo Dorticos delivered a speech in which he pledged to remove his ‘defensive’ weapons in return for the US’s guarantee of non-aggression against his country. U Thant took full advantage of this communist propaganda to form a feasible solution in the crisis; pressing on a deal for exchanging the American invasion of Cuba with dismantling its missile sites. The Secretary-General had used a brilliant tactic to turn the Cubans back on their words. With a new hope of ending the crisis arisen, both Khrushchev and Kennedy accepted this new proposal to discuss with their respective advisors.

On 26 th October, U Thant once again, proposed another agreement; that, he would lead a UN team to Cuba in order to discuss about the dismantling of the missiles. During this period of negotiation, he requested Cuba to halt all of its military construction. At the same time, he proposed a pretense UN observation of the English Thor missiles so as to “save the Russians’ face,” in order to present his impartiality. He then sent a cable to inform Premier Castro of Cuba and in turn, received an invitation to Havana. The crisis was swiftly expected to come to an end.

- Third Phase: Mission to Cuba

All optimism was shattered when Khrushchev sent an agreement on 27 th October to fulfill U Thant’s deal only if the Americans withdrew their Jupiter Missiles in Turkey. Rejected by the Turkish Government to follow Khrushchev’s demand, the US had no other choice but to agree with the Joints Chief of Staff’s plan to invade Cuba on 28 th or 29 th of October.

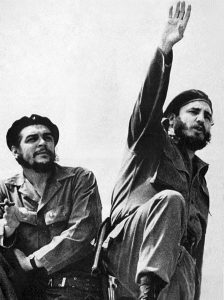

To make matters worse, on 28 th October, Premier Fidel Castro sent a cable to Kennedy stating that the president’s guarantees were inadequate unless he included the following: “cessation of the piratical acts from Puerto Rico, economic blockade, subversive activities, violation of Cuban airspace, and withdrawal of US forces from Guantanamo.” Furthermore, a U-2 American pilot had been reported to be missing after being attacked over Cuba. In fact, Castro even appeared to be forcing the Russians to commence a nuclear invasion against the US.

Due to the rising tension, U Thant decided to make an immediate trip to Havana to consult with Castro himself. The New York Times quoted: “Thant’s Cuba Talks Fruitful; He Will Fly to Havana Today; Blockade Halted during Trip.”

The Secretary-General organized two groups of UN personnel: the first group with seventeen important security officers, while the second group comprised nineteen people including military staff and communication officers. U Thant had planned thoroughly to leave with the first team and would summon the second team upon achieving permission from Castro to observe the dissembling of the missiles in Cuba as soon as possible.

Unfortunately, without informing the Secretary-General, the UN people had arranged twenty-eight pieces of luggage of “communications equipment, supplies, typewriters and other paraphernalia,” to carry out a UN supervision in Cuba. Bringing in such materials without consent from Castro would evolve into a conflict between the UN negotiators and the Cubans. Despite being furious, U Thant did not reveal his anger as he had always controlled his feelings no matter how dire the consequences he faced. Remaining calm, he brought an end to the confusion by revealing the truth to the Cubans; that, the equipment had been brought without his authorization and that, they would be returned to the plane. Without this instant action, the entire mission could have failed immediately.

On 30 th October, U Thant’s first meeting in Havana with Castro was a failure. Even though Thant had stressed on the plea for trading the US’s pledge of not invading Cuba for UN’s supervision of dismantling the Cuban missile sites, as agreed by Khrushchev, Castro bluntly rejected this offer. This might be due to Castro’s desire to gain power as a strong military leader of Cuba by possessing these offensive weapons. In addition, he might not believe the US’s promise of not invading Cuba, and so, could not accept U Thant’s proposal.

The very same day, U Thant received good news from a Soviet general; that, the Soviet had begun disassembling the missiles in Cuba and would complete the operation by 2 nd November. This was encouraging news not only for the national security of the US, but also for the world to avoid a nuclear warfare.

On 31 st October, despite Thant's second meeting with Castro remaining futile, he still managed to persuade Castro to return the body of the US pilot, Major Rudolph Anderson. Returning to New York, U Thant could conclude that his trip to Cuba had been fairly successful; he had acquired direct information of withdrawal of missiles in Cuba as well as retrieved the US pilot’s body.

From 1 st to 20 th November, U Thant continued to serve as a mediator to ensure an absolute cessation of the crisis. During this time, he achieved consent from Castro, in agreement from both the US and the USSR, to send the ICRC (International Committee of Red Cross) to verify the uprooting of missiles in Cuba, instead of the UN observers. On 20 th November, after the US air surveillance of the withdrawal of Soviet bombers in Cuba, Kennedy lifted the quarantine. The Cuban missile crisis had come to an end.

The following results have been obtained from the UN’s intervention in the Cuban missile crisis:

- Dismantle of the Soviet nuclear missiles from Cuba

- US’s pledge with USSR of not invading Cuba

- Fidel Castro became a stronger military leader of Cuba due to the disappearance of foreign invasion

- Peace prevailed regionally and globally preventing nuclear warfare

- Reputation of U Thant acknowledged by the world

From this historical event, we can learn the lesson that resolving a crisis by peaceful means such as table-talks, negotiations and political discussions, mediated by the United Nations, are better than military option. An early UN intervention prevented the eruption of war unlike U Thant’s late intercession during the Vietnam War (1 st November 1955-30 th April 1975). Due to numerous battles between the US and the Communists, there were thousands of Vietnamese and Americans causalities along with the downfall in the economic activities of the country. Cuba, Russia and the United States had all managed to avoid unnecessary casualties as a result of the third Secretary-General’s endeavor to achieve world peace.

Throughout the whole crisis, the Secretary-General had taken thorough approaches to resolution. By announcing his statements publicly or sending unbiased, effective appeals to the respective leaders, a great impact had been made on the result of the negotiation. The contents of these messages, in which he requested both the United States and the Soviet Union leaders to perform certain actions, indicated his neutral position when mediating between the superpowers. No matter the consequences he faced, such as when the nations reached the brink of war even during the negotiation, U Thant managed to deescalate the tension. He even travelled to Cuba to negotiate personally with its leader, Fidel Castro, when the latter rejected the plan of dismantling the missile sites, and also went to the extent of persuading Castro to return the body of the U-2 American pilot. All these events presented U Thant’s unyielding efforts in bringing peace to the conflict.

However, the Soviets, including the Soviet Union Ambassador Valery Zorin, had argued that they had their rights to bring shipments to Cuba as they were travelling on an international route, and claimed that the United States was manipulating the Secretary-General to gain their advantage in the crisis. On the other hand, the Americans protested that they, too, had their rights to protect their country from the threat of nuclear weapons in Cuba. Despite these biased claims, the duty of a UN Secretary-General was to solve the crisis requested by the nations' leaders, as U Thant had accomplished to do so and had received much praise for it.

On 7 th January 1963, Ambassadors Stevenson and Kuznetsov sent a joint letter of gratitude to U Thant stating that they wished to express to him their gratitude for his efforts in helping their Governments to escape the threat to peace which previously occurred in the Caribbean area. Stevenson would also pointed out that the solution to the crisis “was a classic example of performance by the United Nations in the manner contemplated by the Charter…It provided through the Secretary-General…the means of conciliation, of mediation and of negotiation.” Truly, U Thant’s exertions in facilitating tactful and ingenious unbiased proposals as well as transmitting de-escalating messages have influenced the negotiations overpoweringly.

Though U Thant had received support from both superpowers while bringing end to the conflict, it would not have been possible to overcome the real possibility of war without the Secretary-General himself. As President John F. Kennedy quoted, “U Thant has put the world deeply in his debt.” As a result, U Thant had played a crucial part as a neutral figure in keeping the peace and preventing the nuclear warfare between the United States and the Soviet Union.

- Bibliography

Abram Chayes, International Crises and the Role of Law: The Cuban Missile Crisis, London, 1974.

Ernest R. May, Philip Zelikow , eds., The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House during the Cuban Missile Crisis, Harvard University Press (HUP), 1997 .

Laurence Chang and Peter Kornbluh, The Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962: A National

Security Archive Document Reader, New York: The New Press, 1992.

James G. Hershberg, “Russian Documents,” Cold War International History Project Bulletin, n.p., n.d.

Ramses Nassif, U Thant in New York, 1961-1971, A Portrait of the Third UN Secretary-General, C. Hurst & Company, London, 1988.

Richard Ned Lebow, “Domestic Politics and the Cuban Missile Crisis: The Traditional and Revisionist Interpretations Reevaluated,” Journal of Diplomatic History , 14 (Fall 1990).

Robert F. Kennedy, Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis, W. W. Norton & Company, 1969.

U Thant, View from the UN, Garden City, N.Y: Doubleday, 1978.

Editorial New York Times, October 25; October 27; October 30, 1962.

Gertrude Samuels, “The Meditation of U Thant,” New York Times Magazine , December 13, 1964.

Websites-URLs

A. Walter Dorn and Robert Pauk, The Cuban Missile Crisis Resolved: "Untold Story of an Unsung Hero," Ottawa Citizen. Walter Dorn, 22 Oct. 2007: A12. Web. 6 Jan. 2010

(< http://www.walterdorn.org/pub/8>).

Edward C. Keefer and Erin R Mahan, eds. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969-1976: SALT I, 1969-1972. Volume XXXII. Washington, DC: United States Government Publication Office, 2010

(< >).

Graham Allison - Foreign Affairs - The Cuban Missile Crisis at 50: “Lessons for U.S. Foreign Policy Today,” July/August 2012

(< http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/137679/graham-allison/the-cuban-missile-crisis-at-50>).

Hla Oo's Blog - 1974 U Thant Uprising - Former UNSG U Thant (< >).

Michael Dobbs - The National Security Archive - One Minute to Midnight: "Kennedy, Khrushchev and Castro on the Brink of Nuclear War," 18th June 2008 (< >).

Oracle Education Foundation - The Cuban Missile Crisis- Fourteen Days in October (< >).

October 27, 1962: U.S. and U.S.S.R. in confrontation at U.N. Security Council (< >).

Picture of U Thant - Havel's House of the History: Autographs of Leaders of the United Nations, 6 (< >).

Picture of Poltava on its way to Cuba - About Facts Net - Cuban Missile Crisis Pictures 1 (<http://aboutfacts.net/DocsCubanMissleCrisisPictures1.htm>).

Sergei Khrushchev - “How My Father and President Kennedy Saved the World,” n.d., 26 February 2010

(<http://www.americanheritage.com/content/how-my-father-and-president-kenedy-savedworld>).

Appendix 1: Dr. Than Naing Personal Interview Transcript

11 th September, 2012

39, Kyauk Myaung Township, Yangon

Z.K.Z: What do you understand by the UN's Secretary-General?

T.N: According to some books, the article (1) 4 of the UN Charter states that he or she is one who handles administration, gathers human resources, peacekeeping and mediation. In my point of view, I believe the last two features that define a Secretary-General are most significant. After all, the need for that person is to minimize international conflicts, that is, to maintain peace for as much as possible.

Z.K.Z: Even as a Burmese citizen, U Thant managed to become a Secretary-General. Can you explain how he had achieved this distinguished position?

T.N: To start with, I want to explain briefly about U Thant’s life from his birth in 1909. Although he had been born into a wealthy Burmese merchant family and became a high school headmaster, he could not, of course, attempt to accomplish this feat alone. He needed support, which was given by his friend, U Nu, who was then Burma’s prime minister. First, he became secretary to the prime minister and then, received the honor of being the Burmese representative to the United Nations.

After the death of the second Secretary-General, Dag Hammarskjold, in a plane crash on his mission to Congo on 18 th September 1961, the Soviet Union under Khrushchev proposed the Troika plan to the UN to appoint three UN Secretary-Generals to precede Hammarskjold, one representing the Communist world, one for the West, and one for the group of non-aligned nations. But, the United States opposed the plan and immediately decided to choose the third Secretary-General, one from a neutral nation. On 3 rd November 1961, U Thant of Burma was appointed the position of an acting UN Secretary-General and then on 30 th November 1962, the third permanent Secretary-General. He was chosen due to his previous efforts in giving birth to the Non-Aligned Movement, as well as his contributions in the Congo Crisis, working under Hammarskjold.

Z.K.Z: Among his greatest accomplishments, which do you think has revealed U Thant’s strength to maintain the role as the head of the United Nations?

T.N: It is true that he has tackled numerous disputes and wars such as the West Iranian problem, the Borneo problem, the Cyprus crisis, the Prague Spring, the Congo civil war, and the India-Pakistan war, but, his contribution in ending the Cuban Missile crisis is the most well-recognized. During this crisis, which was also one of the most challenging problems encountered by the Secretary-General, he exposed his potential of mediating between the two adversaries, the US and the USSR, as well as maintained peace throughout the discussions to overcome the imminent calamity of a nuclear warfare.

So, I think it is acceptable for him to be awarded the title ‘Maha Thray Sithu,’ by the Burmese government in 1961, and also the ‘Jawaharlal Nehru Award for International Understanding,’ by the Indian government in 1965. He lived up to these titles when he demonstrated his strenuous efforts in the Cuba crisis, and therefore, is appointed to serve the second term at the United Nations.

Z.K.Z: Can you say that U Thant has acted as an important figure in solving the Cuban missile crisis?

T.N: The Secretary-General was, of course, a very significant person since he acted as a medium through which the conflicting nations had communicated. Without him, I am sure that a nuclear war…the third World War would have started then.

Z.K.Z: Do you believe U Thant remained as a neutral figure all this time?

T.N: Some people, especially the Russians, claim that U Thant was being controlled by the US government while the Americans stated that he was just acting independently. I agree with what the Americans say because according to many books and articles I have read about him, he is an impartial person and does not follow others’ biased orders if he doesn’t see any benefit to the situation.

Z.K.Z: How do you think the world, including you, view this man?

T.N: U Thant, through bringing resolutions to international conflicts, has gained immense popularity from many nations. However, with the disappointment he has caused in the Arab-Israel conflict and his negative view towards the Americans' attack on Vietnam, his relationships with Israel and the US deteriorated rapidly.

Despite his strengths and weaknesses, I am still proud to be a Burmese citizen to know that another of us has climbed to the peak of the world and has been awarded praise for handling numerous critical international conflicts.

Z.K.Z: Do you think that he has achieved his role as a peace keeper till his death?

T.N: An irony is present in this case. On 25 th November 1971, three years after his resignation from the UN, U Thant passed away due to lung cancer. While he has accomplished the role as a conciliator throughout his personal life as well as his terms as a Secretary-General at the UN, his death leads to a civil war in his native land, Burma. Since he is a friend of U Nu, the military leader General Ne Win planned to make a common funeral for the late Secretary-General and even decided to bury him at a distant cemetery in Kyandaw. Raged and inflamed, thousands of demonstrators, including monks and University students, rampaged around Yangon, setting fire to buildings. Sadly, many of these rioters were arrested by the Burmese military government and the remains of U Thant were sealed in a mausoleum near the Shwedagon Pagoda. Such tragedy happened to the body of a person who had embraced peace and loathed violence throughout his life.

Figure I: U Thant, Secretary-General of the United Nations (1961–1972)

Figure II: US Ambassador Adlai Stevenson displays photos of Soviet missiles in Cuba at the UN Security Council meeting of October 25, 1962.

Fig III: Location of Soviet missile sites and airfields in Cuba (1962)

Fig V: U Thant’s mausoleum on Shwedagon Pagoda Rd., Yangon

List of Weaponry on the Indigirka bound for Mariel, Cuba on 4th October:

Abram Chayes, International Crises and the Role of Law: The Cuban Missile Crisis, London, 1974, p. 84.

Richard Ned Lebow, “Domestic Politics and the Cuban Missile Crisis: The Traditional and Revisionist Interpretations Reevaluated,” Journal of Diplomatic History, 14 (Fall 1990): pp. 471–92.

Ramses Nassif, U Thant in New York, 1961-1971, A Portrait of the Third UN Secretary-General, C. Hurst & Company, London, 1988, p. 26.

Robert F. Kennedy, Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis, W. W. Norton & Company, 1969, pp. 163–71.

Graham Allison - Foreign Affairs - The Cuban Missile Crisis at 50: “Lessons for U.S. Foreign Policy Today,” July/August 2012.

Ernest R. May, Philip Zelikow , eds., The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House during the Cuban Missile Crisis, Harvard University Press (HUP), 1997 , pp. 372–88.

Ibid. , p. 372.

Ramses Nassif, U Thant in New York, 1961-1971, A Portrait of the Third UN Secretary-General, C. Hurst & Company, London, 1988, pp. 28, 29.

U Thant, View from the UN, Garden City, N.Y: Doubleday, 1978, p. 164.

Ramses Nassif, U Thant in New York, 1961-1971, A Portrait of the Third UN Secretary-General, C. Hurst & Company, London, 1988, p. 30.

U Thant, View from the UN, Garden City, N.Y: Doubleday, 1978, p. 165.

New York Times, October 25, 1962, p. 1.

Adlai Stevenson, Hearings before the Subcommittee on International Organization Affairs,

Senate Foreign Relations Committee, 88th Congress, 1st Session (March 13, 1963): p. 7.

Sergei Khrushchev, “How My Father and President Kennedy Saved the World,” n.d., 26 February 2010.

Edward C. Keefer and Erin R Mahan, eds. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969-1976: SALT I, 1969-1972. Volume XXXII. Washington, DC: United States Government Publication Office, 2010,pp. 185–87.(< >).

Ibid., pp. 191–92.

Robert F. Kennedy, Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis, W. W. Norton & Company, 1969, pp. 190–91.

Ibid., pp. 187–88.

Ernest R. May, Philip Zelikow , eds., The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House during the Cuban Missile Crisis, Harvard University Press (HUP), 1997 , pp. 428-29.

New York Times, October 27, 1962, p. 8.

U Thant, View from the UN, Garden City, N.Y: Doubleday, 1978, p. 464.

Ramses Nassif, U Thant in New York, 1961-1971, A Portrait of the Third UN Secretary-General, C. Hurst & Company, London, 1988, p. 29.

Ernest R. May, Philip Zelikow , eds., The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House during the Cuban Missile Crisis, Harvard University Press (HUP), 1997 , pp. 484–85.

Ramses Nassif, U Thant in New York, 1961-1971, A Portrait of the Third UN Secretary-General, C. Hurst & Company, London, 1988, p. 31.

Edward C. Keefer and Erin R Mahan, eds. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969-1976: SALT I, 1969-1972. Volume XXXII. Washington, DC: United States Government Publication Office, 2010, pp. 258-259.

Ramses Nassif, U Thant in New York, 1961-1971, A Portrait of the Third UN Secretary-General, C. Hurst &Company, London, 1988, p. 32.

Ernest R. May, Philip Zelikow , eds., The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House during the Cuban Missile Crisis, Harvard University Press (HUP), 1997 , p. 520.

Ibid. , p. 688.

New York Times, October 30, 1962, p. 1.

Ramses Nassif, U Thant in New York, 1961-1971, A Portrait of the Third UN Secretary-General, C. Hurst & Company, London, 1988, p. 33.

Ramses Nassif, U Thant in New York, 1961-1971, A Portrait of the Third UN Secretary-General, C. Hurst & Company, London, 1988, p. 32.

Ibid., p. 33.

Ibid., p. 34.

Ibid., p. 35.

“Russian Documents,” CWIHPB , p. 293.

Ramses Nassif, U Thant in New York, 1961-1971 , A Portrait of the Third UN Secretary-General, C. Hurst & Company, London, 1988, p. 37.

ABC-TV, “Adlai Stevenson Reports,” December 23, 1962.

Gertrude Samuels, “The Meditation of U Thant,” New York Times Magazine , December13, 1964, p. 115.

Primary Resource: Interview with U Thant's grand-nephew, Dr. Than Naing

Picture of U Thant - Havel's House of the History: Autographs of Leaders of the United Nations, p 6.

(<http://www.havelshouseofhistory.com/Autographs%20of%20Leaders%20of%20the%20UN%20Page%206.htm>)

October 27, 1962: U.S. and U.S.S.R. in confrontation at U.N. Security Council (<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/October_1962>)

Oracle Education Foundation - The Cuban Missile Crisis- Fourteen Days in October (<http://library.thinkquest.org/11046/days/index.html>)

Picture of Poltava on its way to Cuba - About Facts Net - Cuban Missile Crisis Pictures 1 (<http://aboutfacts.net/DocsCubanMissleCrisisPictures1.htm>)

Hla Oo's Blog - 1974 U Thant Uprising - Former UNSG U Thant

(< http://hlaoo1980.blogspot.com/2010/10/1974-u-thant-uprising.html>)

Michael Dobbs - The National Security Archive - One Minute to Midnight: "Kennedy, Khrushchev and Castro on the Brink of Nuclear War," 18th June 2008 (<http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/nsa/cuba_mis_cri/dobbs/warheads.htm>)

Document Details

- Author Type Student

- Word Count 6177

- Page Count 27

- Level International Baccalaureate

- Subject History

- Type of work Research assignment (e.g. EPQs)

Related Essays

Investigation: The Cuban Missile Crisis as a Thaw in the Cold War

Extended Essay: Columbus's Actions in the New World

Extended Essay - "to what extent was Yellow journalism to blame for instiga...

Explain the USAs policy of containment. How successful was this in Korea, V...

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 8

- John F. Kennedy as president

- Bay of Pigs Invasion

- Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis

- Lyndon Johnson as president

- Vietnam War

- The Vietnam War

- The student movement and the antiwar movement

- Second-wave feminism

- The election of 1968

- 1960s America

- In October 1962, the Soviet provision of ballistic missiles to Cuba led to the most dangerous Cold War confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union and brought the world to the brink of nuclear war.

- Over the course of two extremely tense weeks, US President John F. Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev negotiated a peaceful outcome to the crisis.

- The crisis evoked fears of nuclear destruction, revealed the dangers of brinksmanship , and invigorated attempts to halt the arms race.

The Cuban Revolution

Origins of the cuban missile crisis, negotiating a peaceful outcome, consequences of the cuban missile crisis, what do you think.

- Sergo Mikoyan, The Soviet Cuban Missile Crisis: Castro, Mikoyan, Kennedy, Khrushchev, and the Missiles of November (Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 2012), 225-226.

- Strobe Talbott, ed. Khrushchev Remembers (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1970), 494.

- See Michael Dobbs, One Minute to Midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro on the Brink of Nuclear War (New York: Random House, 2008); and Timothy Naftali and Aleksandr Fursenko, One Hell of a Gamble: Khrushchev, Castro, and Kennedy, 1958-1964: The Secret History of the Cuban Missile Crisis (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1997).

- See James G. Blight and Philip Brenner, Sad and Luminous Days: Cuba’s Struggle with the Superpowers after the Cuban Missile Crisis (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002).

- Paul S. Boyer, Promises to Keep: The United States since World War II (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1999), 179.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Cuban Missile Crisis

By: History.com Editors

Updated: April 20, 2023 | Original: January 4, 2010

During the Cuban Missile Crisis, leaders of the U.S. and the Soviet Union engaged in a tense, 13-day political and military standoff in October 1962 over the installation of nuclear-armed Soviet missiles on Cuba, just 90 miles from U.S. shores. In a TV address on October 22, 1962, President John F. Kennedy (1917-63) notified Americans about the presence of the missiles, explained his decision to enact a naval blockade around Cuba and made it clear the U.S. was prepared to use military force if necessary to neutralize this perceived threat to national security. Following this news, many people feared the world was on the brink of nuclear war. However, disaster was avoided when the U.S. agreed to Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev’s (1894-1971) offer to remove the Cuban missiles in exchange for the U.S. promising not to invade Cuba. Kennedy also secretly agreed to remove U.S. missiles from Turkey.

Discovering the Missiles

After seizing power in the Caribbean island nation of Cuba in 1959, leftist revolutionary leader Fidel Castro (1926-2016) aligned himself with the Soviet Union . Under Castro, Cuba grew dependent on the Soviets for military and economic aid. During this time, the U.S. and the Soviets (and their respective allies) were engaged in the Cold War (1945-91), an ongoing series of largely political and economic clashes.

Did you know? The actor Kevin Costner (1955-) starred in a movie about the Cuban Missile Crisis titled Thirteen Days . Released in 2000, the movie's tagline was "You'll never believe how close we came."

The two superpowers plunged into one of their biggest Cold War confrontations after the pilot of an American U-2 spy plane piloted by Major Richard Heyser making a high-altitude pass over Cuba on October 14, 1962, photographed a Soviet SS-4 medium-range ballistic missile being assembled for installation.

President Kennedy was briefed about the situation on October 16, and he immediately called together a group of advisors and officials known as the executive committee, or ExComm. For nearly the next two weeks, the president and his team wrestled with a diplomatic crisis of epic proportions, as did their counterparts in the Soviet Union.

A New Threat to the U.S.

For the American officials, the urgency of the situation stemmed from the fact that the nuclear-armed Cuban missiles were being installed so close to the U.S. mainland–just 90 miles south of Florida . From that launch point, they were capable of quickly reaching targets in the eastern U.S. If allowed to become operational, the missiles would fundamentally alter the complexion of the nuclear rivalry between the U.S. and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), which up to that point had been dominated by the Americans.

Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev had gambled on sending the missiles to Cuba with the specific goal of increasing his nation’s nuclear strike capability. The Soviets had long felt uneasy about the number of nuclear weapons that were targeted at them from sites in Western Europe and Turkey, and they saw the deployment of missiles in Cuba as a way to level the playing field. Another key factor in the Soviet missile scheme was the hostile relationship between the U.S. and Cuba. The Kennedy administration had already launched one attack on the island–the failed Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961–and Castro and Khrushchev saw the missiles as a means of deterring further U.S. aggression.

Watch the three-episode documentary event, Kennedy . Available to stream now.

Kennedy Weighs the Options

From the outset of the crisis, Kennedy and ExComm determined that the presence of Soviet missiles in Cuba was unacceptable. The challenge facing them was to orchestrate their removal without initiating a wider conflict–and possibly a nuclear war. In deliberations that stretched on for nearly a week, they came up with a variety of options, including a bombing attack on the missile sites and a full-scale invasion of Cuba. But Kennedy ultimately decided on a more measured approach. First, he would employ the U.S. Navy to establish a blockade, or quarantine, of the island to prevent the Soviets from delivering additional missiles and military equipment. Second, he would deliver an ultimatum that the existing missiles be removed.

In a television broadcast on October 22, 1962, the president notified Americans about the presence of the missiles, explained his decision to enact the blockade and made it clear that the U.S. was prepared to use military force if necessary to neutralize this perceived threat to national security. Following this public declaration, people around the globe nervously waited for the Soviet response. Some Americans, fearing their country was on the brink of nuclear war, hoarded food and gas.

HISTORY Vault: Nuclear Terror

Now more than ever, terrorist groups are obtaining nuclear weapons. With increasing cases of theft and re-sale at dozens of Russian sites, it's becoming more and more likely for terrorists to succeed.

Showdown at Sea: U.S. Blockades Cuba

A crucial moment in the unfolding crisis arrived on October 24, when Soviet ships bound for Cuba neared the line of U.S. vessels enforcing the blockade. An attempt by the Soviets to breach the blockade would likely have sparked a military confrontation that could have quickly escalated to a nuclear exchange. But the Soviet ships stopped short of the blockade.

Although the events at sea offered a positive sign that war could be averted, they did nothing to address the problem of the missiles already in Cuba. The tense standoff between the superpowers continued through the week, and on October 27, an American reconnaissance plane was shot down over Cuba, and a U.S. invasion force was readied in Florida. (The 35-year-old pilot of the downed plane, Major Rudolf Anderson, is considered the sole U.S. combat casualty of the Cuban missile crisis.) “I thought it was the last Saturday I would ever see,” recalled U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara (1916-2009), as quoted by Martin Walker in “The Cold War.” A similar sense of doom was felt by other key players on both sides.

A Deal Ends the Standoff

Despite the enormous tension, Soviet and American leaders found a way out of the impasse. During the crisis, the Americans and Soviets had exchanged letters and other communications, and on October 26, Khrushchev sent a message to Kennedy in which he offered to remove the Cuban missiles in exchange for a promise by U.S. leaders not to invade Cuba. The following day, the Soviet leader sent a letter proposing that the USSR would dismantle its missiles in Cuba if the Americans removed their missile installations in Turkey.

Officially, the Kennedy administration decided to accept the terms of the first message and ignore the second Khrushchev letter entirely. Privately, however, American officials also agreed to withdraw their nation’s missiles from Turkey. U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy (1925-68) personally delivered the message to the Soviet ambassador in Washington , and on October 28, the crisis drew to a close.

Both the Americans and Soviets were sobered by the Cuban Missile Crisis. The following year, a direct “hot line” communication link was installed between Washington and Moscow to help defuse similar situations, and the superpowers signed two treaties related to nuclear weapons. The Cold War was and the nuclear arms race was far from over, though. In fact, another legacy of the crisis was that it convinced the Soviets to increase their investment in an arsenal of intercontinental ballistic missiles capable of reaching the U.S. from Soviet territory.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- About WordPress

- Get Involved

- WordPress.org

- Documentation

- Learn WordPress

- Cuban Missile Crisis

Contextual Essay

Topic: How did the Cuban Missile Crisis affect the United States’ foreign policy in Cuba during the Cold War?

- Introduction

Despite the short geographical distance between the two countries, Cuba and the United States have had a complicated relationship for more than 150 years owing to a long list of historical events. Among all, the Cuban Missile Crisis is considered as one of the most dangerous moments in both the American and Cuban history as it was the first time that these two countries and the former Soviet Union came close to the outbreak of a nuclear war. While the Crisis revealed the possibility of a strong alliance formed by the former Soviet Union and Cuba, two communist countries, it also served as a reminder to U.S. leaders that their past strategy of imposing democratic ideology on Cuba might not work anymore and the U.S. needed a different approach. It was lucky that the U.S. was able to escape from a nuclear disaster in the end, how did the Cuban Missile Crisis affect the U.S. foreign policy in Cuba during the Cold War?

To answer my research question, I searched on different academic databases related to Latin American studies, history, and political science. JSTOR, Hispanic American Historical Review, and Journal of American History were examples of databases that I used. I also put in keywords like “Cuban Missile Crisis,” “Cuba and the U.S.,” and “U.S. cold war foreign policy” to find sources that are related to my research focus. Furthermore, I have included primary and secondary sources that address the foreign policies the U.S. implemented before and after the Cuban Missile Crisis. In order to provide a more comprehensive picture of the impact of the Crisis on the U.S. foreign policy in Cuba, the primary sources used would include declassified CIA documents, government memos, photos, and correspondence between leaders. These sources would be the best for my project because they provided persuading first-hand information for analyzing the issue. I cut sources that were not trustworthy and did not relate to my topic. This research topic was significant because it reflected the period when Cuban-U.S. relations became more negative. By understanding the change in foreign policy direction after the Cuban Missile Crisis, we could gain a better understanding of the development of Cuban-U.S. relations since the Cold War. On top of that, it was also a chance for us to reflect upon the decision-making process and learn from the past.

In my opinion, the Cuban Missile Crisis affected U.S. foreign policy in Cuba during the Cold War in three ways. First, the Crisis allowed the U.S. government to realize the importance of flexible and planned crisis management. Second, the Crisis reinforced the U.S. government’s belief in the Containment Policy. Third, the Crisis reminded the U.S. of the importance of multilateralism when it came to international affairs.

In October 1962, the United States detected that the former Soviet Union had deployed medium-range missiles in Cuba. This discovery then led to a tense standoff that lasted for 13 days, which was later known as the Cuban Missile Crisis. In response to the Soviet Union’s action, the Kennedy administration quickly placed a “quarantine” naval blockade around Cuba and demanded the destruction of missile sites. [1] This decision was made carefully by the U.S. government because any miscalculation would lead to a nuclear war between Cuba, the U.S.S.R. and the U.S. After weighing possible options, the former Soviet Union finally announced the removal of missiles for an American pledge not to reinvade Cuba. [2] On the other hand, the U.S. also agreed to secretly remove its nuclear missiles from Turkey in a separate deal. [3] The Crisis was then over and the three countries involved were able to escape from a detrimental nuclear crisis.

After World War II, the United States and the former Soviet Union began battling indirectly through a plethora of ways like propaganda, economic aid, and military coalitions. This was known as the period of the Cold War. [4] The Cuban Missile Crisis happened amid the Cold War then caused the escalation of tension between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. Despite the removal of nuclear missiles by the U.S.S.R., Moscow still decided to upgrade the Soviet nuclear strike force. This decision allowed the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. to further their nuclear arms race as a result. [5] The Cold War tensions only softened after the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty was negotiated and signed by both superpowers. [6] Additionally, both the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. reflected upon the dangerous nuclear crisis and established the “Hotline” to reduce the possibility of war by miscalculation. [7]

- Crisis management

To begin, the success of solving the Cuban Missile Crisis has proven to the U.S. the importance of planning and flexibility when it came to crisis management with a tight time limit. This was supported by the CIA document “Major Consequences of Certain U.S. Courses of Action on Cuba” and the Dillon group discussion paper “Scenario for Airstrike Against Offensive Missile Bases and Bombers in Cuba.” Rather than devoting to existing plans, the Kennedy administration came up with flexible plans. Depending on the potential reactions of Cuba towards different hypothetical scenarios of the United States’ response after the deployment of Soviet nuclear weapons in Cuba, the CIA document listed several modes of blockade and warnings that the U.S. could use to avoid a nuclear war. [8] The CIA document also presented the meanings of different military strategies to the U.S., the U.S.S.R., and Cuba.[9] In addition, the Dillon group discussion paper included the advantages and disadvantages of using airstrikes against Cuba.[10] Not only did these documents reveal the careful planning process that the U.S. government underwent under a pressurized time limit, but they also allowed the U.S. government to realize the uncertainty in the U.S.-Cuban relations and the U.S.-Soviet relations. The U.S. would need to have flexible military plans prepared to protect itself from a similar crisis and to sustain harmonious relationships with the U.S.S.R. and Cuba in the long run.

- Containment Policy

Furthermore, the Cuban Missile Crisis has allowed the U.S. government to reflect upon the extent of the application of the Containment Policy to prevent the spread of communism. Since the U.S. became a superpower after World War II, it seldom faced threat from countries that were close to its border. The Crisis then was an opportunity for the U.S. to learn that it was possible that itself could be trapped by the “containment policy” by other communist countries like the Soviet Union and Cuba. This could explain why the U.S. chose not to invade or attack Cuba but to compromise with the U.S.S.R. by trading nuclear missiles for those in Cuba, despite intended to actively suppress communism. [11]

As mentioned in the White House document, “two extreme views on the proper role of force in the international relations were wrong – the view which rejects force altogether as an instrument of foreign policy; and the view that force can solve everything,” the Crisis made the U.S. understand that forceful use of containment policy on communist countries might not work all the time. [12] The U.S. would need to change its focus and turn to other diplomatic strategies to better protect its national interest.

- Multilateralism

In addition, the success of solving the Cuban Missile Crisis allowed the United States to understand the importance of multilateralism when it came to international conflicts with communist countries. Amid the Crisis, the U.S. actively sought support from different countries. This was clearly noted in the CIA daily report “The Crisis USSR/Cuba” that many countries like Spain, France, and Venezuela showed public support for the U.S. quarantine blockade policy on Cuba.[13] On top of the support of other countries, the U.S. also sought justification of the quarantine through the Organization of American States and made good use of the United Nations to communicate with the Soviets on the size of the quarantine zone.[14] All these measures made it difficult for Moscow or Cuba to further escalate the Crisis or interpret American actions as a serious threat to their interests. With the clever use of multilateralism, the U.S. was able to minimize the danger of the Crisis smoothly before any escalation of tensions. This experience also served as a good resource for solving troubling diplomatic problems with Cuba or other communist countries in the future.

In conclusion, the Cuban Missile Crisis has several effects on the United States’ foreign policy in Cuba during the Cold War. To begin, the success of solving the Cuban Missile Crisis has proven to the U.S. the importance of planning and flexibility when it came to crisis management with a tight time limit. Additionally, the Cuban Missile Crisis has allowed the U.S. government to reflect upon the extent of the application of the Containment Policy to prevent the spread of communism. Furthermore, the Cuban Missile Crisis provided the United States a chance to understand the importance of multilateralism when it came to solving international conflicts with communist countries. By understanding more about the effects that the Cuban Missile Crisis had on U.S. foreign policy in Cuba, we were able to realize the vulnerability and insecurity in Cuban-U.S. relations. This allowed us to gain a more diverse view of the causes of the conflicting U.S.-Cuban relations in the 20th and 21st centuries.

- Primary Sources (10-15 sources)

CIA Special National Intelligence Estimate, “Major Consequences of Certain U.S. Courses of Action on Cuba,” October 20, 1962. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nsa/cuba_mis_cri/19621020cia.pdf.

CIA daily report, “The Crisis USSR/Cuba,” October 27, 1962. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nsa/cuba_mis_cri/621027%20The%20Crisis%20USSR-Cuba.pdf

Dillon group discussion paper, “Scenario for Airstrike Against Offensive Missile Bases and Bombers in Cuba,” October 25, 1962. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nsa/cuba_mis_cri/19621025dillon.pdf

White House, “Post Mortem on Cuba,” October 29, 1962. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nsa/cuba_mis_cri/19621029mortem.pdf

John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. “Cuban Missile Crisis,” Accessed February 25, 2020. https://microsites.jfklibrary.org/cmc/ .

The U-2 Plane. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nsa/cuba_mis_cri/19.jpg

October 5, 1962: CIA chart of “reconnaissance objectives in Cuba.”

Graphic from Military History Quarterly of the U.S. invasion plan, 1962.

CIA reference photograph of Soviet cruise missile in its air-launched configuration.

October 17, 1962: U-2 photograph of first IRBM site found under construction.

[1] “The Cold War,” JFK Library, accessed May 5, 2020, https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/jfk-in-history/the-cold-war .

[3] “Cuban Missile Crisis.” JFK Library. Accessed May 5, 2020. https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/jfk-in-history/cuban-missile-crisis.

[4] “The Cold War,” JFK Library, accessed May 5, 2020, https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/jfk-in-history/the-cold-war .

[8] CIA Special National Intelligence Estimate, “Major Consequences of Certain U.S. Courses of Action on Cuba,” October 20, 1962. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nsa/cuba_mis_cri/19621020cia.pdf .

[10] Dillon group discussion paper, “Scenario for Airstrike Against Offensive Missile Bases and Bombers in Cuba,” October 25, 1962. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nsa/cuba_mis_cri/19621025dillon.pdf

[11] CIA Special National Intelligence Estimate, “Major Consequences of Certain U.S. Courses of Action on Cuba,” October 20, 1962. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nsa/cuba_mis_cri/19621020cia.pdf .

[12] White House, “Post Mortem on Cuba,” October 29, 1962. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nsa/cuba_mis_cri/19621029mortem.pdf

[13] CIA daily report, “The Crisis USSR/Cuba,” October 27, 1962. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nsa/cuba_mis_cri/621027%20The%20Crisis%20USSR-Cuba.pd

[14] “TWE Remembers: The OAS Endorses a Quarantine of Cuba (Cuban Missile Crisis, Day Eight).” Council on Foreign Relations. Accessed May 4, 2020. https://www.cfr.org/blog/twe-remembers-oas-endorses-quarantine-cuba-cuban-missile-crisis-day-eight.

- Modern History

Thirteen days that shook the world - The Cuban Missile Crisis

By 1962, the Cold War was in full swing. The Soviet Union and the United States were locked in a struggle for global supremacy.

Each side trying to outdo the other in terms of military power and political influence.

This led to a major standoff between the two superpowers, known as the Cuban Missile Crisis.

For thirteen days in October 1962, the world held its breath as it waited to see if a full-blown nuclear war would break out.

Ultimately, cooler heads prevailed and a diplomatic solution was reached.

The Cuban Revolution

Before the 1960s, Cuba was ruled by a corrupt dictator named Fulgencio Batista. Under Batista's rule, American businesses had a great deal of control over the Cuban economy.

American businesses owned most of Cuba’s public railways, almost half the sugar industry, and 90% of the telephone and electric companies.

In 1959, a revolutionary group led by Fidel Castro overthrew Batista's government.

Once in power, Castro wanted to minimise America’s control on Cuba's economy.

His new Cuban government seized American businesses and nationalised them.

The United States was not happy about this turn of events. The American government saw Castro's regime as a threat to its interests in the region.

In response, the U.S. began working to overthrow the Cuban government.

The Bay of Pigs Invasion

In 1961, the CIA hatched a plan to overthrow Castro. The plan was to train and arm Cuban exiles and then send them back to invade their homeland.

The exiles were trained in Guatemala and then flown to Cuba in CIA-owned aircraft.

They landed in April 1961 at the Bay of Pigs in Cuba, but the invasion was a complete disaster.

The failure was largely due to the lack of support from the local population and the absence of the anticipated U.S. air support.

The exiles were quickly defeated, and many were captured or killed. The debacle served as a humiliating embarrassment for the United States.

Following the invasion, Castro turned to the Soviet Union for help. He knew that the Soviets had nuclear weapons, and he hoped that they would be deter the United States from trying to overthrow his regime.

Secret missiles to Cuba

In 1962, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev decided to take advantage of Castro's vulnerability.

He secretly ordered Soviet ballistic missiles to be placed in Cuba. The missiles were capable of reaching most of the United States, including major cities like Washington D.C., New York City, and Miami.

In addition to the nuclear missiles, the USSR had also managed to send 40,000 Soviet troops to Cuba.

These were both combat-ready soldiers, but also the engineers and technicians required to assemble and fire the missiles.

These secret movements of missiles and men was in response to the U.S. stationing Jupiter ballistic missiles in Turkey, which was aimed at the Soviet Union.

These American missiles had been placed in Turkey in 1960, and the Soviets saw them as a direct threat, as they could strike the USSR within five minutes of being launched.

The Crisis Begins

On the 14th of October 1962, American spy planes discovered the Soviet missiles in Cuba and President John F Kennedy was faced with a difficult decision: should he order a strike against the missile sites, or should he try to negotiate with the Soviets?

Further plane photographs on the 15th of October showed they the build-up continued.

Kennedy convened a meeting of his top advisors to discuss what to do. The options were to do nothing, launch a military attack on Cuba, or impose a naval blockade on Cuba.

After much deliberation, Kennedy decided on the latter option. On the 22nd of October, he appeared on American TV and announced that the United States would impose a naval blockade of Cuba until the Soviet Union agreed to remove the missiles.

This was known as a "quarantine" rather than a blockade, so as not to provoke the Soviets into taking military action.

For a day and a half, during the 24th and 25h of October, some Soviet ships that were heading for Cuba were turned back from the U.S. quarantine line, but further spy photographs showed that the missiles were still in place on Cuba.

Kennedy's advisors said that all missiles would be operational within three days and were capable of reaching American targets within 10 minutes of launch.

The president asked for an estimated death toll if the US was hit. He was told that each missile was capable of killing 600,000 people each.

Then, on the morning of Saturday, October 27th, an American U-2 spy plane was shot down by a Soviet-operated surface-to-air missile as it flew over Cuba.

The pilot of the U-2, named Major Rudolf Anderson, was killed, and the US Joint Chiefs of Staff were outraged. They encouraged Kennedy to launch a retaliatory air strike on the missile bases.

However, fearing that such an attack would begin a nuclear war, Kennedy refused.

Instead, late on Saturday evening, the president sent an offer to Khrushchev.

The Cuban Missile Crisis finally ended on the 28th of October with a secret agreement between the United States and the Soviet Union.

The United States agreed to remove its nuclear missiles from Turkey and promised not to invade Cuba.

In return, the Soviet Union agreed to remove its missiles from Cuba and to not place any more nuclear weapons on the island.

The world breathed a sigh of relief, and the crisis was over.

Consequences

The Cuban Missile Crisis was a turning point in the Cold War. It showed that both sides were capable of destroying the other, and that diplomacy was necessary to avoid such a catastrophe.

The experience also led to increased cooperation between the United States and the Soviet Union in order to prevent future conflicts.

The Cuban Missile Crisis was a watershed moment not just for American-Soviet relations, but for international politics as well.

Specifically, it led to the establishment of the Moscow-Washington hotline in 1963, which was a direct communication link between the leaders of the two nations.

The fact that two superpowers with such different ideologies were able to come to a diplomatic resolution in such a short amount of time is a testament to the power of communication and negotiation.

It is a reminder that, even in the darkest of times, cooler heads can still prevail.

Further reading

What do you need help with, download ready-to-use digital learning resources.

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2024.

Contact via email

National Museum of Nuclear Science & History

Nuclear Close Calls: The Cuban Missile Crisis

- Cold War History

During the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union were largely prevented from engaging in direct combat with each other due to the fear of mutually assured destruction (MAD). In 1962, however, the Cuban Missile Crisis brought the world perilously close to nuclear war.

“Why not throw a hedgehog at Uncle Sam’s pants?”

Soviet General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev’s decision to put nuclear missiles in Cuba was precipitated by two major developments. The first was the rise of the Cuban communist movement, which in 1959 overthrew President Fulgencio Batista and brought Fidel Castro to power. The Cuban Revolution was an affront to the United States, which took control of the island following the Spanish-American War of 1898. After granting Cuba its independence several years later, the United States remained a close ally. Under the directive of President Dwight D. Eisenhower, the CIA prepared to overthrow the Castro government. The resulting Bay of Pigs Invasion, ordered by President John F. Kennedy in April 1961, saw the defeat of approximately 1,500 American-trained Cuban exiles at the hands of the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces.

The Soviet Union, meanwhile, was motivated to assist the fledgling communist government that had somewhat surprisingly come to power without any support or influence from Moscow. Despite the Americans’ humiliating defeat at the Bay of Pigs, the Soviets feared that the United States would continue to oppose and delegitimize the Castro regime. As Khrushchev explained, “The fate of Cuba and the maintenance of Soviet prestige in that part of the world preoccupied me. We had to think up some way of confronting America with more than words. We had to establish a tangible and effective deterrent to American interference in the Caribbean. But what exactly? The logical answer was missiles” (Gaddis 76).

The other factor which led Khrushchev to his decision was the disparity between American and Soviet nuclear capabilities. According to physicist Pavel Podvig, Soviet bombers at the time “could deliver about 270 nuclear weapons to U.S. territory.” By contrast, the United States had thousands of warheads that it could deliver via 1,576 Strategic Air Command bombers as well as 183 Atlas and Titan intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), 144 Polaris missiles via nine nuclear submarines, and ten newly-built Minuteman ICBMs (Rhodes 93).

The Soviets did not yet have a reliable source of ICBMs, but they did have effective medium-range ballistic missiles (MRBMs) and intermediate-range ballistic missiles (IRBMs). If these weapons were deployed in Cuba, only 90 miles from the American mainland, it would in the eyes of Khrushchev equalize “what the West likes to call the ‘balance of power’” (Sheehan 438). From the Soviet perspective, nuclearizing Cuba would also serve as an effective response to the American Jupiter missiles deployed in Turkey. “Why not throw a hedgehog at Uncle Sam’s pants?” quipped Khrushchev at a meeting in April 1962 (Gaddis 75).

Operation Anadyr

From July to October 1962, the Soviets secretly transported troops and equipment to Cuba. If all went according to plan, the Americans would find out about the operation only after it was too late to stop it. 41,902 soldiers were deployed—most wearing civilian clothes and introduced to an unconvinced Cuban population as “agricultural specialists”—before the crisis started. Thirty-six R-12 missiles and twenty-four launchers were successfully deployed on the island as well as a number of tactical cruise missiles designed to stop an invading American force (Sheehan 441). After the end of the Cold War, Russian officials revealed that 162 nuclear weapons were stationed in Cuba when the crisis broke out (Rhodes 99).

The CIA was unaware of the operation until October, as it had little presence in Cuba following the Bay of Pigs fiasco. Furthermore, a series of international incidents involving U-2 spy planes had caused the United States to put a five-week moratorium on aerial reconnaissance over Cuba. The missions resumed on October 14, when Air Force Major Richard Heyser flew over the island and recorded video evidence of the R-12 sites. Coupled with information from Colonel Oleg Penkovsky, a CIA spy in the Soviet Military Intelligence, there was no denying the harsh truth: the Soviet Union was deploying missiles in Cuba.

Quarantining Nuclear Missiles

Kennedy wisely ruled out a military strike, noting that it was likely to miss at least some of the missiles and would prompt Soviet retaliation, probably against a vulnerable West Berlin. He ultimately chose the second option proposed by the CIA, but with one crucial difference. Rather than publicly calling it a “blockade,” which as McCone noted would have required a declaration of war, Kennedy instead termed it a “quarantine.” His military advisers nevertheless continued to push for an attack, to which Kennedy sardonically quipped, “These brass hats have one great advantage in their favor. If we listen to them, and do what they want us to do, none of us will be alive later to tell them that they were wrong” (Sheehan 445). Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara later affirmed that an American invasion would have prompted Soviet forces in Cuba “to use their nuclear weapons rather than lose them” (Rhodes 100).

Kennedy announced the blockade on October 22 in a speech that evoked the Monroe Doctrine, a nineteenth century policy which established the United States’ sphere of influence in the Western Hemisphere by opposing any future European colonization in the Americas: “It shall be the policy of this nation to regard any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western Hemisphere as an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response upon the Soviet Union.” Kennedy also ordered the Strategic Air Command (SAC) into Defense Condition 3 (DEFCON 3) and two days later upped it to DEFCON 2, only one step short of nuclear war. Among other preparations, 66 B-52s carrying hydrogen bombs were constantly airborne, replaced with a fresh crew every 24 hours.

The gambit was designed to exert maximum pressure on the Soviet Union. U.S. officials made sure that the Soviets would pick up the communications ordering the American nuclear forces on high alert. At the United Nations, American Ambassador Adlai Stevenson famously sparred with Soviet Ambassador Valerian Zorin over the crisis. “Well, let me say something to you, Mr. Ambassador—we do have the evidence [of missile sites],” asserted Stevenson. “We have it, and it is clear and it is incontrovertible. And let me say something else—those weapons must be taken out of Cuba” (Hanhimaki and Westad 485).

The B-59 Submarine

Perhaps the most dangerous moment of the Cuban Missile Crisis came on October 27, when U.S. Navy warships enforcing the blockade attempted to surface the Soviet B-59 submarine. It was one of four submarines sent from the Soviet Union to Cuba, all of which were detected and three of which were eventually forced to surface. The diesel-powered B-59 had lost contact with Moscow for several days, and thus was not informed of the escalating crisis. With its air conditioning broken and battery failing, temperatures inside the submarine were above 100ºF. Crew members fainted from heat exhaustion and rising carbon dioxide levels.

American warships tracking the submarine dropped depth charges on either side of the B-59 as a warning. The crew, unaware of the blockade, thought that perhaps war had been declared. Vadim Orlov, an intelligence officer aboard the submarine, recalled how the American ships “surrounded us and started to tighten the circle, practicing attacks and dropping depth charges. They exploded right next to the hull. It felt like you were sitting in a metal barrel, which somebody is constantly blasting with a sledgehammer.”

Unbeknownst to the Americans, the B-59 was equipped with a T-5 nuclear-tipped torpedo. It was capable of a blast equivalent to 10 kilotons of TNT, roughly two-thirds the strength of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima. Firing without a direct order from Moscow, however, required the consent of all three senior officers on board. Orlov remembered Captain Valentin Savitsky shouting, “We’re going to blast them now! We will die, but we will sink them all—we will not disgrace our Navy!” Political officer Ivan Semonovich Maslennikov agreed that they should launch the torpedo.

The last remaining officer, Second Captain Vasili Alexandrovich Arkhipov, dissented. They did not know for sure that the ship was under attack, he argued. Why not surface and then await orders from Moscow? In the end, Arkhipov’s view prevailed. The B-59 surfaced near the American warships and the submarine set off north to return to the Soviet Union without incident.

Armageddon Averted

Although the Americans and the Soviets ultimately reached an agreement, it took almost a week of tense negotiations following the institution of the blockade. Meanwhile, the fate of the world continued to hang in the balance. On October 26, Khrushchev sent a private letter to Kennedy proposing a resolution to the crisis: “We, for our part, will declare that our ships, bound for Cuba, will not carry any kind of armaments. You would declare that the United States will not invade Cuba with its forces and will not support any sort of forces which might intend to carry out an invasion of Cuba. Then the necessity for the presence of our military specialists in Cuba would disappear.” A deal was on the table—the Soviet Union would remove the missiles if the United States was willing to accept Castro’s communist regime in Cuba.