Our Favorite Essays by Black Writers About Race and Identity

Books & Culture

A personal and critical lens to blackness in america from our archives.

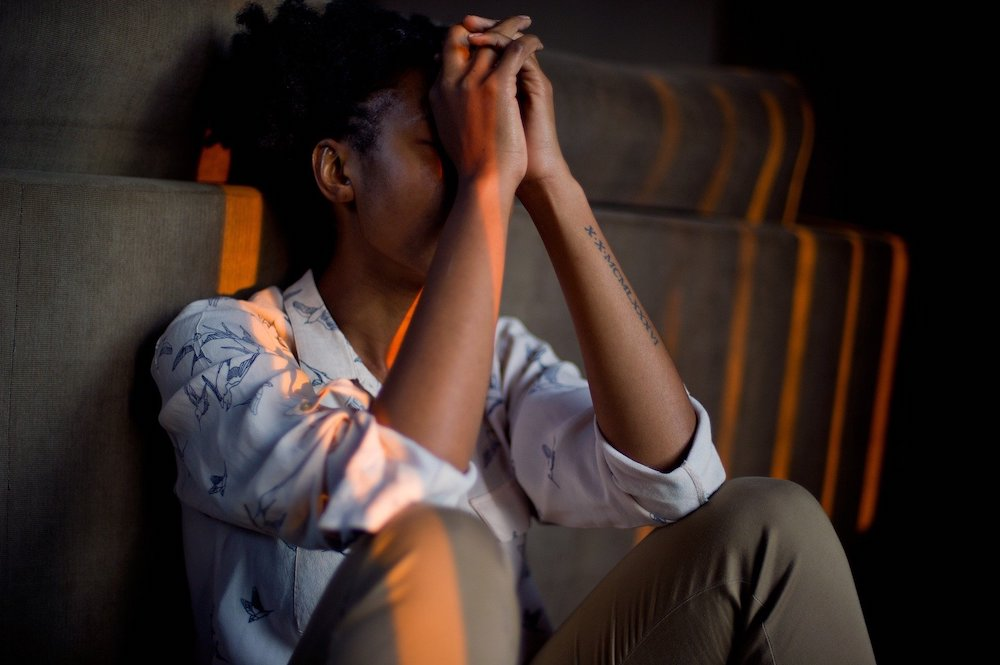

It’s fitting that two of the first three essays in this roundup are centered on examining the Black American experience as one of horror. In a year when radical right-wing activists are truly leaning in, we’ve already seen record numbers of anti-LGBTQ legislation, the very real possibility of the end of Roe v. Wade, and more fervent redlining measures to keep Black people (and other marginalized communities) from voting. Gun violence is at an all time high, in particular mass shootings.

Since the success of Jordan Peele’s runaway hit film Get Out , there has been a steady rise in films depicting the Black American experience for the fraught, nuanced, dangerous life that it can be. This narrative isn’t entirely new, but this is the first time these films have gained critical acclaim and commercial attention. The reason is simple. Whatever the cause—social media, an increasingly diverse population—America can’t run from itself anymore. Our entertainment is finally asking the question that Black people have been asking for generations: In America, who is the real boogeyman?

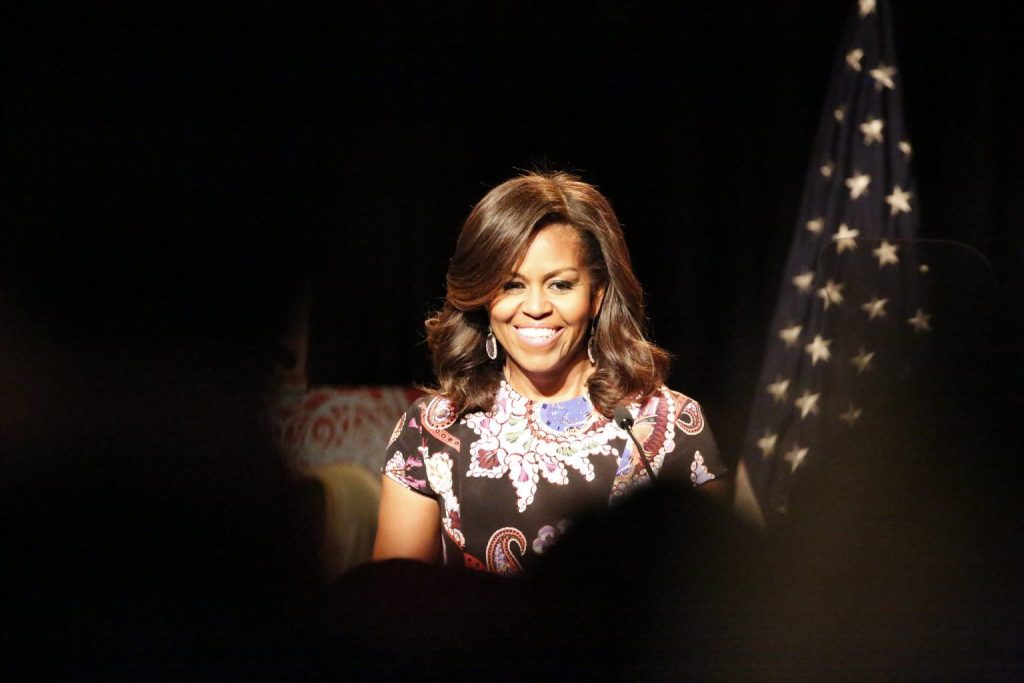

Naturally, the discourse and critical analyses must follow suit. But it doesn’t stop there: the essays on this list span far and wide when it comes to subject matter, critical lens, and personal narrative. There are essays about Black friendship, the radical nature of Black people taking rest, and the affirmation of Black women writing for themselves, telling their own stories. Icons like Michelle Obama, Toni Morrison, and Gayle Jones get a deep dive, and we learn that we should always have been listening to Octavia Butler. This Juneteenth, I hope you’re taking a moment to reflect, on America’s troubled legacy, and to celebrate the ways that Black people continue to thrive.

Modern Horror Is the Perfect Genre for Capturing the Black Experience

Cree Myles writes about the contemporary Black creators rewriting the horror genre and growing the canon:

“Racism is a horror and should be explored as such. White folks have made it clear that they don’t think that’s true. Someone else needs to tell the story.”

Modern Narratives of Black Love and Friendship Are Centering Iconic Trios

Darise Jeanbaptiste writes about how Insecure and Nobody’s Magic illustrate the intricacy of evolving Black relationships:

“The power of the triptych is that it offers three experiences in addition to the fourth, which emerges when all three are viewed or read together.”

I Was Surrounded by “Final Girls” in School, Knowing I’d Never Be One

Whitney Washington writes that the erasure of Black women in slasher films has larger implications about race in America:

“Long before the realities of American life, it was slasher movies that taught me how invisible, ignored, and ultimately expendable Black women are. There was no list of rules long enough to keep me safe from the insidiousness of white supremacy… More than anything, slasher movies showed me that my role was to always be a supporting character, risking my life to be the voice of reason ensuring that the white girl makes it to the finish line.”

“Palmares” Is An Example of What Grows When Black Women Choose Silence

Deesha Philyaw, author of The Secret Lives of Church Ladies , writes that Gayl Jones’ decades-long absence from public life illuminates the power of restorative quiet:

“These women’s silences should not be interpreted as a lack of understanding or awareness, but rather as an abundance of both, most especially the knowledge of what to keep close to the vest, and the implications for failing to do so. They know better than to explain themselves, their powers and their origins, their beliefs and reasons, their magic. These women are silent not because they don’t know anything. They are silent because they know better.”

Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye” Showed Me How Race and Gender Are Intertwined

For the 50th anniversary of Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye , Koritha Mitchell writes how the novel taught her that being a Black woman is more than just Blackness or womanhood:

“I didn’t have the gift of Kimberlé Crenshaw’s concept of ‘intersectionality,’ but The Bluest Eye revealed how, in my presence, racism and sexism would always collide to produce negative experiences that others could dodge. It was not simply being Black or being dark-skinned that mattered; it was being those things while also being female.”

The Delicate Balancing Act of Black Women’s Memoir

Koritha Mitchell writes about how Michelle Obama’s Becoming illustrates larger tensions for Black women writing about themselves:

“In other words, when Black women remain enigmas while seeming to share so much, they create proxies at a distance from their psychic and spiritual realities because they are so rarely safe in public. Despite the release of her memoir, audiences will never be privy to who Michelle Obama actually knows herself to be, and that is more than appropriate.”

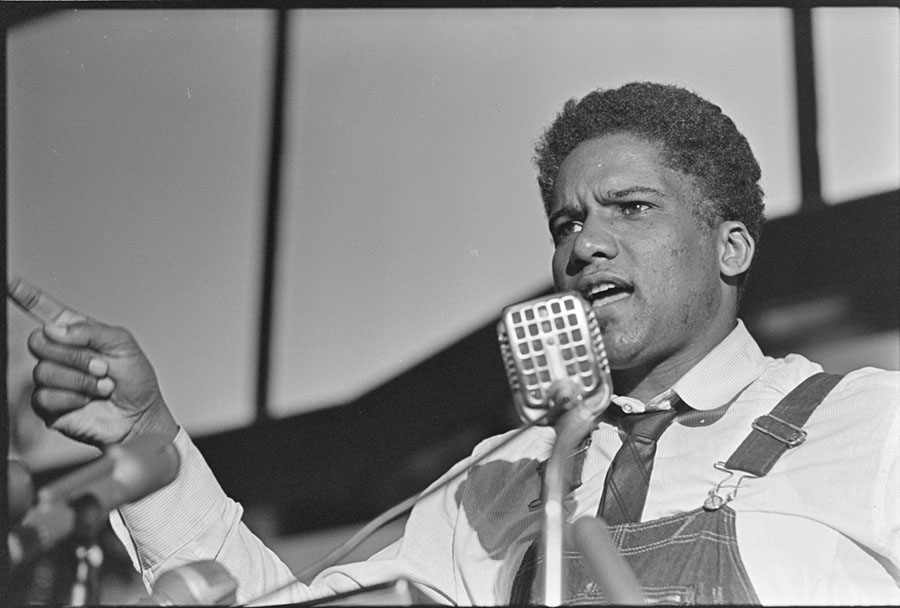

50 Years Later, the Demands of “The Black Manifesto” Are Still Unmet

Carla Bell writes about James Forman’s famous 1969 address, The Black Manifesto , and its contemporary resonances:

“But the Manifesto is as vital a roadmap in our marches and protests today as the day it was first delivered. We, black people in America, remain compelled by the power and purpose of The Black Manifesto, and we continue to demand our full rights as a people of this decadent society.”

You Should Have Been Listening to Octavia Butler This Whole Time

Alicia A. Wallace writes that Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower isn’t just a prescient dystopia—it’s a monument to the wisdom of Black women and girls:

Through her protagonist Lauren Olamina, Butler has been telling the world for decades that it was not going to last in its capitalist, racist, sexist, homophobic form for much longer. She showed us the way injustice would cause the earth to burn, and the importance of community building for survival and revolution. Through Parable of the Sowe r, we had a better future in our hands, but we did not listen.

The Book You Need to Fully Understand How Racism Operates in America

Darryl Robertson writes about Ibram X. Kendi’s Stamped from the Beginning and its examination of the history of overt and covert bigotry:

“While How to Be an Antiracist is an informative and necessary read, it is his National Book Award-winning, Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America that deserves extra attention. If we want to uproot the current racist system, it’s mandatory that we understand how racism was constructed. Stamped does just that.”

I Reject the Imaginary White Man Judging My Work

Tracey Michae’l Lewis-Giggetts turns to Black writers as inspiration for resisting white expectations:

“…it doesn’t only matter that I’m a Black woman telling my story. What matters is the lens through which I’m telling it. And sometimes, many times, that lens, if we’re not careful, can be tainted by the ever-present consciousness of Whiteness as the default.”

Toni Morrison Gave My Own Story Back to Me

The incomparable literary powerhouse showed Brandon Taylor how to stop letting white people dictate the shape of his narrative:

“That’s the magic of Toni Morrison. Once you read her, the world is never the same. It’s deeper, brighter, darker, more beautiful and terrible than you could ever imagine. Her work opens the world and ushers you out into it. She resurfaced the very texture and nature of my imagination and what I could conceive of as possible for writing and for art, for life.”

Art Must Engage With Black Vitality, Not Just Black Pain

Jennifer Baker writes that books like The Fire This Time give depth and nuance to a reflection of Blackness in America:

“These essays provided a deeper connection because Black pain was part of the story; Black identity, self-recognition, our own awareness brokered every page. Black pain was not the sole criterion for the anthology’s existence.”

When Black Characters Wear White Masks

Jennifer Baker writes that whiteface in literature isn’t a disavowal of Blackness, but a commentary on privilege:

“Whiteface stories interrogate the mentality that it’s better to be white while examining how societal gains as well as societal “norms” inflict this way of thinking on Black people. Being white isn’t better, but, for some of these characters, it seems a hell of a lot easier, or at least preferable to dealing with racism.”

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven't read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.

ARTICLE CONTINUES AFTER ADVERTISEMENT

Traveling South to Understand the Soul of America

Imani Perry examines how the history of slavery, racism, and activism in the South has shaped the entire country

Jun 17 - Deirdre Sugiuchi Read

More like this.

In “James,” Percival Everett Does More than Reimagine “Huck Finn”

The author discusses writing from the perspective of Jim and language as a tool of oppression

Mar 19 - Bareerah Ghani

The Stakes of Driving While Black Are Unconscionably High

"Wedding Season (A Nocturne for Sandra Bland)," excerpted from the essay collection "You Get What You Pay For"

Mar 12 - Morgan Parker

10 Memoirs and Essay Collections by Black Women

These contemporary books illuminate the realities of the world for Black women in America

Nov 29 - Alicia Simba

DON’T MISS OUT

Sign up for our newsletter to get submission announcements and stay on top of our best work.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Check your paper for plagiarism in 10 minutes, generate your apa citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- College essay

- How to Write a Diversity Essay | Tips & Examples

How to Write a Diversity Essay | Tips & Examples

Published on November 1, 2021 by Kirsten Courault . Revised on May 31, 2023.

Table of contents

What is a diversity essay, identify how you will enrich the campus community, share stories about your lived experience, explain how your background or identity has affected your life, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about college application essays.

Diversity essays ask students to highlight an important aspect of their identity, background, culture, experience, viewpoints, beliefs, skills, passions, goals, etc.

Diversity essays can come in many forms. Some scholarships are offered specifically for students who come from an underrepresented background or identity in higher education. At highly competitive schools, supplemental diversity essays require students to address how they will enhance the student body with a unique perspective, identity, or background.

In the Common Application and applications for several other colleges, some main essay prompts ask about how your background, identity, or experience has affected you.

Why schools want a diversity essay

Many universities believe a student body representing different perspectives, beliefs, identities, and backgrounds will enhance the campus learning and community experience.

Admissions officers are interested in hearing about how your unique background, identity, beliefs, culture, or characteristics will enrich the campus community.

Through the diversity essay, admissions officers want students to articulate the following:

- What makes them different from other applicants

- Stories related to their background, identity, or experience

- How their unique lived experience has affected their outlook, activities, and goals

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Think about what aspects of your identity or background make you unique, and choose one that has significantly impacted your life.

For some students, it may be easy to identify what sets them apart from their peers. But if you’re having trouble identifying what makes you different from other applicants, consider your life from an outsider’s perspective. Don’t presume your lived experiences are normal or boring just because you’re used to them.

Some examples of identities or experiences that you might write about include the following:

- Race/ethnicity

- Gender identity

- Sexual orientation

- Nationality

- Socioeconomic status

- Immigration background

- Religion/belief system

- Place of residence

- Family circumstances

- Extracurricular activities related to diversity

Include vulnerable, authentic stories about your lived experiences. Maintain focus on your experience rather than going into too much detail comparing yourself to others or describing their experiences.

Keep the focus on you

Tell a story about how your background, identity, or experience has impacted you. While you can briefly mention another person’s experience to provide context, be sure to keep the essay focused on you. Admissions officers are mostly interested in learning about your lived experience, not anyone else’s.

When I was a baby, my grandmother took me in, even though that meant postponing her retirement and continuing to work full-time at the local hairdresser. Even working every shift she could, she never missed a single school play or soccer game.

She and I had a really special bond, even creating our own special language to leave each other secret notes and messages. She always pushed me to succeed in school, and celebrated every academic achievement like it was worthy of a Nobel Prize. Every month, any leftover tip money she received at work went to a special 509 savings plan for my college education.

When I was in the 10th grade, my grandmother was diagnosed with ALS. We didn’t have health insurance, and what began with quitting soccer eventually led to dropping out of school as her condition worsened. In between her doctor’s appointments, keeping the house tidy, and keeping her comfortable, I took advantage of those few free moments to study for the GED.

In school pictures at Raleigh Elementary School, you could immediately spot me as “that Asian girl.” At lunch, I used to bring leftover fun see noodles, but after my classmates remarked how they smelled disgusting, I begged my mom to make a “regular” lunch of sliced bread, mayonnaise, and deli meat.

Although born and raised in North Carolina, I felt a cultural obligation to learn my “mother tongue” and reconnect with my “homeland.” After two years of all-day Saturday Chinese school, I finally visited Beijing for the first time, expecting I would finally belong. While my face initially assured locals of my Chinese identity, the moment I spoke, my cover was blown. My Chinese was littered with tonal errors, and I was instantly labeled as an “ABC,” American-born Chinese.

I felt culturally homeless.

Speak from your own experience

Highlight your actions, difficulties, and feelings rather than comparing yourself to others. While it may be tempting to write about how you have been more or less fortunate than those around you, keep the focus on you and your unique experiences, as shown below.

I began to despair when the FAFSA website once again filled with red error messages.

I had been at the local library for hours and hadn’t even been able to finish the form, much less the other to-do items for my application.

I am the first person in my family to even consider going to college. My parents work two jobs each, but even then, it’s sometimes very hard to make ends meet. Rather than playing soccer or competing in speech and debate, I help my family by taking care of my younger siblings after school and on the weekends.

“We only speak one language here. Speak proper English!” roared a store owner when I had attempted to buy bread and accidentally used the wrong preposition.

In middle school, I had relentlessly studied English grammar textbooks and received the highest marks.

Leaving Seoul was hard, but living in West Orange, New Jersey was much harder一especially navigating everyday communication with Americans.

After sharing relevant personal stories, make sure to provide insight into how your lived experience has influenced your perspective, activities, and goals. You should also explain how your background led you to apply to this university and why you’re a good fit.

Include your outlook, actions, and goals

Conclude your essay with an insight about how your background or identity has affected your outlook, actions, and goals. You should include specific actions and activities that you have done as a result of your insight.

One night, before the midnight premiere of Avengers: Endgame , I stopped by my best friend Maria’s house. Her mother prepared tamales, churros, and Mexican hot chocolate, packing them all neatly in an Igloo lunch box. As we sat in the line snaking around the AMC theater, I thought back to when Maria and I took salsa classes together and when we belted out Selena’s “Bidi Bidi Bom Bom” at karaoke. In that moment, as I munched on a chicken tamale, I realized how much I admired the beauty, complexity, and joy in Maria’s culture but had suppressed and devalued my own.

The following semester, I joined Model UN. Since then, I have learned how to proudly represent other countries and have gained cultural perspectives other than my own. I now understand that all cultures, including my own, are equal. I still struggle with small triggers, like when I go through airport security and feel a suspicious glance toward me, or when I feel self-conscious for bringing kabsa to school lunch. But in the future, I hope to study and work in international relations to continue learning about other cultures and impart a positive impression of Saudi culture to the world.

The smell of the early morning dew and the welcoming whinnies of my family’s horses are some of my most treasured childhood memories. To this day, our farm remains so rural that we do not have broadband access, and we’re too far away from the closest town for the postal service to reach us.

Going to school regularly was always a struggle: between the unceasing demands of the farm and our lack of connectivity, it was hard to keep up with my studies. Despite being a voracious reader, avid amateur chemist, and active participant in the classroom, emergencies and unforeseen events at the farm meant that I had a lot of unexcused absences.

Although it had challenges, my upbringing taught me resilience, the value of hard work, and the importance of family. Staying up all night to watch a foal being born, successfully saving the animals from a minor fire, and finding ways to soothe a nervous mare afraid of thunder have led to an unbreakable family bond.

Our farm is my family’s birthright and our livelihood, and I am eager to learn how to ensure the farm’s financial and technological success for future generations. In college, I am looking forward to joining a chapter of Future Farmers of America and studying agricultural business to carry my family’s legacy forward.

Tailor your answer to the university

After explaining how your identity or background will enrich the university’s existing student body, you can mention the university organizations, groups, or courses in which you’re interested.

Maybe a larger public school setting will allow you to broaden your community, or a small liberal arts college has a specialized program that will give you space to discover your voice and identity. Perhaps this particular university has an active affinity group you’d like to join.

Demonstrating how a university’s specific programs or clubs are relevant to you can show that you’ve done your research and would be a great addition to the university.

At the University of Michigan Engineering, I want to study engineering not only to emulate my mother’s achievements and strength, but also to forge my own path as an engineer with disabilities. I appreciate the University of Michigan’s long-standing dedication to supporting students with disabilities in ways ranging from accessible housing to assistive technology. At the University of Michigan Engineering, I want to receive a top-notch education and use it to inspire others to strive for their best, regardless of their circumstances.

If you want to know more about academic writing , effective communication , or parts of speech , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Academic writing

- Writing process

- Transition words

- Passive voice

- Paraphrasing

Communication

- How to end an email

- Ms, mrs, miss

- How to start an email

- I hope this email finds you well

- Hope you are doing well

Parts of speech

- Personal pronouns

- Conjunctions

In addition to your main college essay , some schools and scholarships may ask for a supplementary essay focused on an aspect of your identity or background. This is sometimes called a diversity essay .

Many universities believe a student body composed of different perspectives, beliefs, identities, and backgrounds will enhance the campus learning and community experience.

Admissions officers are interested in hearing about how your unique background, identity, beliefs, culture, or characteristics will enrich the campus community, which is why they assign a diversity essay .

To write an effective diversity essay , include vulnerable, authentic stories about your unique identity, background, or perspective. Provide insight into how your lived experience has influenced your outlook, activities, and goals. If relevant, you should also mention how your background has led you to apply for this university and why you’re a good fit.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Courault, K. (2023, May 31). How to Write a Diversity Essay | Tips & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 2, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/college-essay/diversity-essay/

Is this article helpful?

Kirsten Courault

Other students also liked, how to write about yourself in a college essay | examples, what do colleges look for in an essay | examples & tips, how to write a scholarship essay | template & example, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

The New York Times

The learning network | what is your racial and ethnic identity.

What Is Your Racial and Ethnic Identity?

Questions about issues in the news for students 13 and older.

- See all Student Opinion »

Multiracial and multiethnic — or “mixed race” — people are a rapidly growing demographic in the United States. And more and more people, especially young people, are embracing and expressing their multifaceted racial and ethnic backgrounds. How about you?

In the article “Black? White? Asian? More Young Americans Choose All of the Above,” Susan Saulny explores how many young people are celebrating their mixed-race identities:

The crop of students moving through college right now includes the largest group of mixed-race people ever to come of age in the United States, and they are only the vanguard: the country is in the midst of a demographic shift driven by immigration and intermarriage. One in seven new marriages is between spouses of different races or ethnicities, according to data from 2008 and 2009 that was analyzed by the Pew Research Center. Multiracial and multiethnic Americans (usually grouped together as “mixed race”) are one of the country’s fastest-growing demographic groups. And experts expect the racial results of the 2010 census, which will start to be released next month, to show the trend continuing or accelerating. Many young adults of mixed backgrounds are rejecting the color lines that have defined Americans for generations in favor of a much more fluid sense of identity. Ask Michelle López-Mullins, a 20-year-old junior and the president of the Multiracial and Biracial Student Association, how she marks her race on forms like the census, and she says, “It depends on the day, and it depends on the options.” They are also using the strength in their growing numbers to affirm roots that were once portrayed as tragic or pitiable. “I think it’s really important to acknowledge who you are and everything that makes you that,” said [Laura] Wood, the 19-year-old vice president of the group. “If someone tries to call me black I say, ‘yes — and white.’ People have the right not to acknowledge everything, but don’t do it because society tells you that you can’t.”

Students: Tell us about your race and ethnicity. How do you identify yourself and why? Is your background a source of pride, confusion, discomfort or something else? How do others react to your perceived and expressed identity? What does your family tree look like?

Students 13 and older are invited to comment below. Please use only your first name. For privacy policy reasons, we will not publish student comments that include a last name.

Comments are no longer being accepted.

i am a west Indian born and raise in Guyana south america. i only know that i am of Indian decent mixed with British. the reaction of people are completely different when i’m by myself because i look Indian but when i am with my family their reaction are different because my mom and brother complexion are white and my dad and i are dark so the look at us pretty weird

As a great man once said “those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it”. Studying history my prediction towards the situation in Egypt is backed by previous strikes. I feel that if people really want a democracy they will achieve it. Their society has to believe in what they believe is right. Like Gandi’s passive resistance, they will endure hardship but with time justice will be accomplished.

I am from the island of Jamaica in the Caribbean, however I categorize myself as African-American in this country. My ancestors mostly from an African descent so that is why i choose that category. However, Jamaicans are known to have be mixed with some traces of Indian and Irish descent of which i am also part of. I mainly express my main root on required information despite my other roots.

My ethnicity or race is Hispanic and I’m proud of that. Being Mexican and Ecuadorian have basically been my life. It affects my entire lifestyle such as my religion, culture, and eating habits. My mother was born in Veracruz, Mexico and my father in Cuenca, Ecuador. Both came to the United States were I was born to provide me a better life. I embrace my origins and tell people of my culture and once in middle school I was proud to announce it in a school project. We are all different and that is what makes the United States one of a kind.

Although I was born in the United States, my parents are immigrants from Colombia.Because of that, my house revolved around Colombian customs and beliefs. I take a lot of pride in my culture because its the culture that influenced my personality.

I am Chinese and was raised in the United States. I was pushed to do the best in everything even though I was not. I tried my best to achieve all that I can. Most people believe that we Chinese have to be extremely smart or above everyone else. These expectations are extremely high even to my standard. We are taught by our parents to believe that we are above everyone else due to extreme stereotypical views. Happy early Chinese New Year.

I think it should not ever matter what race you are. People sometimes think less of them which is not right at all.

I am Italian and African American and am proud of all of my heritages.

My origins are diverse, but so is the world around me. I grew up in a national forest reserve which lent me a respect for rural America. Growing up, I worked as a Thai souse chef for a Thai immigrant. He taught me to cook and I developed that skill in college where my primary super market in college became Patel’s Cash and Carry.

Two of my best friends best friends are Muslim by way of Bangladesh, but dress like 1930’s French models. One is Polish and Irish who loves her Peruvian gay uncle. The love of my life is a first generation Cuban-American who works for a major East Asian research center.

I am happy to consider myself uniquely American. I could have only happened here.

My origins come from Korea. All my family tree has been Korean. There has not been any interracial marriages in my family. I am proud to be Asian and fully accept my background. There is nothing wrong with anyone’s nationality. I think that interracial marriages are beautiful and that people with mixed nationalities are outstanding since they embrace how they are no matter what others might say about them. Being Korean in a Latin American country, I do hear a lot of things about being Asian. However, I am proud of being Asian and totally accept it.

I am Peruvian, and my mother and father are both Peruvian as well. That would basically make me hispanic. My origins are straight from Peru, however my grandmother from my dads side of the family comes from half-Inca and half-African American descent. But other than that, I’m proud to have mixed ancestry at some point. I came here when I was 4 years old, so my beliefs and traditions haven’t changed from when I was still in Peru, sure America does have more freedom. But no matter what, if you were born here or in your home country, traditions, customs and beliefs still follow you throughout your life. Thats why I love being from a different country, because you get to experience the American way of life and yet still have your family’s customs.

I was born in México and most of my family is Mexican. But I have routs of Spanish and German. I am very proud of who I am and as well of nationality. In my family there is some interracial marriages and we have no problem with it. They only thing I do not like is that the rest of Latin America makes fun of how Mexican speak which I found it very rude because not all Mexicans talk that way. I am very proud of where I come from.

My racial background is very simple. I have basically all European backgrounds, with a slight amount of Native American. I therefore consider myself very much just white. I believe that my race is something to be proud of. I must preserve my culture. My culture is what makes me who I am.

I am white with a very strong European background. I am French, German, and Irish mostly. I love knowing my culture and where I came from.

This artical is very true, some people who are mixed perfer one country more then others. At the same time some times thats how their families raisied them. I am hispanic & been told by my grandmother we are mixed with italian too, but i tell everyone I am hispanic. I dont say I’m italian because i was never raised knowing the Italian culture but i am aware its in my blood.

I’m Mexican and I’m proud of that. Being Mexican is an honor, because our culture is amazing,our food and the way we live the religion most of we have.

I am half puerto rican, a quarter english, and a quarter lithuanain. I don’t know much about my lithuanian background but I am proud of it either way. I am poud too be english because my grandmother, who is english, fled to the US from great britain during WW2 and that, to me, seems special. I am proud to be puerto rican because my grandfather came here from a different country with no prospects and made a life for his family and that, to me, is special. Because I am puerto rican, I am a bit of an outcast on the non-hispanic side of my family. This would probably be why I would identify myself as puerto rican.

I am Irish, German, Napoliatan and Scillian. My mother is a full blooded Italian and she shows much pride for her Scillian heritage, where I like to express my Irish roots from my father’s side. I don’t know too much about my father’s side of the family, but I am very proud to be Irish, its part of my personality.

I am a Spanish, im very proud of what I am were I came from. I love my culture and enjoy about learning were I came from and my family tree.

I’m a quarter Italian and the rest of me is pretty American. I’ve always viewed myself as an American girl. My family barely celebrates our Italian side exept on holidays so I’ve always just seen myself as white. My family itself though has grown to be diverse. My cousin married and Indian woman, my adopted cousin is black and my brother’s girlfriend of 5 years is Portuguese.

I am Black and Puerto Rican and thats what I indentify myself as. I am proud to say that that is what I am because I love the mixture of the both. I do take pride in my ethnicity. When I am perceived as something other than what I am I correct them and let them what I really am.

My mom is Puerto Rican and my dad is African American

I am Hungarian, German, Italian, and Irish. I am very prouto be what i am. My backround i dont know everything about my culture and i wanna learn more things. My family tree is very different

I am latin my whole family is Ecuadorian. I was not born in Ecuador i was born when my family came to the states so i am American . My family tells me to be proud that i am American but i love my culture. The way we speak our traditions and the food we eat is South American.

I am an African American. I am very proud of my heritage. I am a young strong black intelligent young man. I love to learn about the history of my ancestors and other blacks. I love to learn about other heritages along with mine. I do not discriminate. People are who they are no matter what they are, Indian, Black, White, Mexican, and so on. My background is a source of discomfort because when others view us they think about slavery. We are viewed different from others when we are in stores. We are more likely to be watched in stores then other. My family tree is made up of the same race. My family is large in size.

My father is from India, while my mother is of German heritage. My brothers and I all look Indian, and no one can guess that we are half Caucasian. When I was young, I always felt that I couldn’t acknowledge being half-German, because I don’t LOOK like it. But now, I do acknowledge it. Still, people look at me funny and many actually believe I am joking when I say I am half-German.

I tend to closely associate myself with my Celtic ancestry and my Indo-european ancestry in general. I feel closely intertwined with these cultures and so tend to embrace them above others, notably Hungarian, French, and Native American. From a very young age the Celtic socities have fasinated intensly and through independent research I have studied the bulk of information avaliable from both contemporary and ancient sources. This of course led me to delve into the history of the Indo-european peoples and their descendents, many of whom I have also descended from.

What's Next

Read our research on: Abortion | International Conflict | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

Racial & ethnic identity, who are you the art and science of measuring identity.

As a shop that studies human behavior through surveys and other social scientific techniques, we have a good line of sight into the contradictory nature of human preferences. Here's a look at how we categorize our survey participants in ways that enhance our understanding of how people think and behave.

Language and Traditions Are Considered Central to National Identity

Across more than 20 countries surveyed, a median of 91% say being able to speak their country’s most common language is important for being considered a true national. And 81% say sharing their country’s customs and traditions is important for true belonging.

Latinos’ Views of and Experiences With the Spanish Language

Most U.S. Latinos speak Spanish: 75% say they are able to carry on a conversation in Spanish pretty well or very well. But not all Latinos are Spanish speakers, and about half (54%) of non-Spanish-speaking Latinos have been shamed by other Latinos for not speaking Spanish.

Among Asian Americans, U.S.-born children of immigrants are most likely to have hidden part of their heritage

32% of U.S.-born Asian adults have hidden a part of their heritage, compared with 15% of immigrants.

Who is Hispanic?

The Census Bureau estimates there were roughly 63.7 million Hispanics in the U.S. as of 2022, a new high. They made up 19% of the nation’s population.

Diverse Cultures and Shared Experiences Shape Asian American Identities

Among Asian Adults living in the U.S., 52% say they most often describe themselves using ethnic labels that reflect their heritage and family roots, either alone or together with "American." About six-in-ten (59%) say that what happens to Asians in the U.S. affects their own lives.

Documentary: Being Asian in America

In this companion documentary, Asian American participants described navigating their own identity. These participants were not part of our focus group study but were similarly sampled to tell their own stories.

Extended Interviews: Being Asian in America

The stories shared by participants in our video documentary reflect opinions, experiences and perspectives similar to those we heard in the focus groups. Watch extended interviews that were not included in our documentary but present thematically relevant stories.

In Their Own Words: The Diverse Perspectives of Being Asian in America

Use this quote sorter to read how focus group participants answered the question, “What does it mean to be you in America?”

What It Means To Be Asian in America

In a new analysis based on dozens of focus groups, Asian American participants described the challenges of navigating their own identity in a nation where the label “Asian” brings expectations about their origins, behavior and physical self.

Refine Your Results

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

5.8: Strategies for Starting Your Cultural Identity Paper

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 14827

This chapter summarizes a range of different ideas about literature that all center on the identity of authors, their characters, and (in part) their readers. In each paper we find a close consideration of the way different groups interact: how they perceive and represent each other, how they talk to and about each other, and how they exert power against each other. Whether discussing the effects of colonialism in nineteenth-century Africa, the perils of assimilation for Native Americans in the early twentieth-century United States, or the economic parallels between slavery and whaling in nineteenth-century America, each paper takes seriously the cultural and political realities that underlie the creation of literature, and each sees literature as a force that can shape those cultural and political realities. When reading literary works, you should be attentive to issues of identity, power, assimilation, and/or prejudice.

If you follow these steps, you’ll be well on your way to writing a compelling paper on racial, ethnic, or cultural themes:

- Consider the racial, ethnic, or cultural background of the author. Do the characters in the work come from a similar background? Does the author come from a colonized or minority population? Conversely, does the author come from an imperial or majority population? Does the work seem intended to address issues particular to the author’s background?

- Consider the history of the work’s setting and/or composition. What were the major political realities of the day? Were there major conflicts, settlements, or economic realities that would have shaped the author’s or his or her contemporary readers’ worldviews? Are the settings in the work familiar to the author’s experience, or are they “other” or exotic settings? How might the politics of the day shape the work’s themes, images, settings, or characters?

- Research the reactions of previous critics to the work. Have they noticed particular attitudes toward race, ethnicity, or culture in the text? Do you agree with their assessment, or do you see ideas they have missed? Can you extend, modify, or correct their arguments?

- Consider the possible readers of the work. How do you think members of the groups represented in the work would feel about the way their race, ethnicity, or culture is represented? If you come from a group depicted in the work you’ve chosen, how does that depiction make you feel?

In short, you want to ask how the work you are studying represents the identities of the groups it depicts. If you can begin to answer these questions, you’ll be well on your way to a cultural analysis of a literary text. Remember that you can write a cultural analysis in many modes: you can celebrate a work’s progressive representation of race or you can critique a work’s problematic complicity in negative social attitudes. Either way, you can write a compelling argument about race, culture, and ethnicity in literature.

Race & Ethnicity—Definition and Differences [+48 Race Essay Topics]

Race and ethnicity are among the features that make people different. Unlike character traits, attitudes, and habits, race and ethnicity can’t be changed or chosen. It fully depends on the ancestry.

But why do we separate these two concepts and what are their core differences? How do people classify different races and types of ethnicity?

To find answers to these questions, keep reading the article.

Also, if you have a writing assignment on the same topic due soon and looking for inspiration, you’ll find plenty of race, racism, and ethnic group essay examples. At IvyPanda , we’ve gathered over 45 samples to help you with your writing, so you don’t have to torture yourself looking for awesome essay ideas.

Race and Ethnicity Definitions

It’s important to learn what race and ethnicity really are before trying to compare them and explore their classification.

Race is a group of people that belong to the same distinct category based on their physical and social qualities.

At the very beginning of the term usage, it only referred to people speaking a common language. Later, the term started to denote certain national affiliations. A reference to physical traits was added to the term race in the 17th century.

In a modern world, race is considered to be a social construct. In other words, it’s a distinguishable identity with a cultural meaning behind. Race is not usually seen as exclusively biological or physical quality, even though it’s partially based on common physical features among group members.

Ethnicity (also known as ethnic group) is a category of people who have similarities like common language, ancestry, history, culture, society, and nation.

Basically, people inherit ethnicity depending on the society they live in. Other factors that define a person’s ethnicity include symbolic systems like religion, cuisine, art, dressing style, and even physical appearance.

Sometimes, the term ethnicity is used as a synonym to people or nation. It’s also fair to mention that it’s sometimes possible for an individual to leave one ethnic group and shift to another. It’s usually done through acculturation, language shift, or religious conversion.

Though, most of the times, representatives of a certain ethnic group continue to speak their common language and share some other typical traits even if derived from their founder population.

Differences Between Race and Ethnicity

Now that we know what race and ethnicity are all about, let’s highlight some of the major differences between these two terms.

- It divides people into groups or populations based mainly on physical appearance

- The main accent is on genetic or biological traits

- Because of geographical isolation, racial categories were a result of a shared genealogy. In modern world, this isolation is practically nonexistent, which lead to mixing of races

- The distinguishing factors can include type of face or skin color. Other genetic differences are considered to be weak

- Members of an ethnic group identify themselves based on nationality, culture, and traditions

- The emphasis is on group history, culture, and sometimes on religion and language

- Definition of ethnicity is based on shared genealogy. It can be either actual or presumed

- Distinguishing factors of ethnic groups keep changing depending on time period. Sometimes, they get defined by stereotypes that dominant groups have

It’s also worth mentioning that the border between two terms is quite vague . As a result, the choice of using either of them can be very subjective.

In the majority of cases, race is considered to be unitary, which means that one person belongs to one race. However, ethnically, this same person can identify themselves as a member of multiple ethnic groups. And it won’t be wrong if a person have lived enough time within those groups.

Race and Ethnicity Classification

It’s time to look at possible ways to classify racial and ethnical groups.

One of the most common classifications for race into four categories: Caucasoid, Mongoloid, Negroid, and Australoid. Three of them have subcategories.

Let’s look at them more closely.

– Caucasoid. White race with light skin color. Hair ranges from brown to black. They have medium to high structure. The subcategories are as follows:

- Alpine. Live in Central Asia

- Nordic . Baltic, British, and Scandinavian inhabitants

- Mediterranean. Hail from France, Italy, Portugal, and Spain

– Mongoloid. The race’s majority is found in Asia. Characterized by black hair, yellow skin tone, and medium height.

- Asian mongol. Found in japan, China, and East-India

- Micronesian. Inhabitants of Malenesia

– Negroid. A race found in Africa. They have black skin, wooly hair, and medium to high structure.

- Negro. African inhabitants

- Far Eastern Pygmy. Found in the south Pacific islands

- Bushman and Hottentot. Live in Kala-Hari desert of Africa

– Australoid. Found in Australia. They have wavy hair, light skin, and medium to tall height.

It’s fair to mention yet again that it’s practically impossible to find pure race representatives because of how mixed they all got.

Speaking of ethnicity classification, one of the most common ways to do that is by continent. And each of continent’s ethnic groups will have their own subcategory.

So, we can roughly divide ethnic groups into following categories:

- North American

- South American

Race Essay Ideas

If all the information above was not enough and you’re looking for race essay topics, or even straight up essay examples for your writing assignment—today’s your lucky day. Because experts at IvyPanda have gathered plenty of those.

Check out the list of race and ethnic group essay samples below. Use them for inspiration, or try to develop one of the suggested topics even further.

Whatever option you’ll choose, we’re sure that you’ll end up with great results!

- The Anatomy of Scientific Racism: Racialist Responses to Black Athletic Achievement

- Race, Ethnicity and Crime

- Representation of Race in Disney Films

- What is the relationship between Race, Poverty and Prison?

- Race in a Southern Community

- African American Women and the Struggle for Racial Equality

- American Ethnic Studies

- Institutionalized Racism from John Brown Raid to Jim Crow Laws

- The Veil and Muslim

- Race and the Body: How Culture Both Shapes and Mirrors Broader Societal Attitudes Towards Race and the Body

- Latinos and African Americans: Friends or Foes?

- Historical US Relationships with Native American

- The experiences of the Aborigines

- Contemporary Racism in Australia: the Experience of Aborigines

- No Reparations for Blacks for the Injustice of Slavery

- Racism (another variant)

- Hispanic Americans

- Racism in the Penitentiary

- How the development of my racial/ethnic identity has been impacted

- My father’s black pride

- African American Ethnic Group

- Ethnic Group Conflicts

- How the Movie Crash Presents the African Americans

- Ethnic Groups and discrimination

- Race and Ethnicity

- Racial and ethnic inequality

- Ethnic Groups and Conflicts

- Ethnics Studies

- Ethnic studies and emigration

- Ethnicity Influence

- Immigration and Ethnic Relations

- A comparison Between Asian Americans and Latinos

- Analysis of the Chinese Experience in “A Different Mirror: A History of Multicultural America” by Ronald Takaki

- Wedding in the UAE

- Social and Cultural Diversity

- The White Dilemma in South Africa

- Ethnocentrism and its Effects on Individuals, Societies, and Multinationals

- Reduction of ethnocentrism and promotion of cultural relativism

- Racial and Ethnic Groups

- Gender and Race

- Child Marriages in Modern India

- Race and Ethnicity (another variant)

- Racial Relations and Color Blindness

- Multiculturalism and “White Anxiety”

- Cultural and racial inequality in Health Care

- The impact of colonialism on cultural transformations in North and South America

- African American Studies

- Share via Facebook

- Share via Twitter

- Share via LinkedIn

- Share via email

You might also like

![essay on racial identity Make Your Online Research More Effective [9 Super Hacks]](https://ivypanda.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Online-Research-309x208.jpg)

Make Your Online Research More Effective [9 Super Hacks]

How to Plan a Paper to Write on: 9 Ways

How to Avoid Plagiarism – 12 Must-Know Ways

Download: Exploring Equity - Identity and Race (UPDATED)2

Part of CEE’s Exploring Equity Issues series, this brief discusses the strong relationship between identity construction in academics and academic achievement. Educators can support students as they develop their identities and leverage it to improve academic outcomes. We provide research on identity theory and strategies educators can use in the classroom to meet the needs of their students.

Racial Identity, Academic Identity, and Academic Outcomes for Students of Color

Experts in psychology and education have shown a strong relationship between identity construction in academics and academic achievement. Studies show that students’ academic self-perceptions in math and science relate to academic performance (Bouchey & Harter, 2005); students’ perceptions of their academic identities relate to their college aspirations (Howard, 2003); and identity matters in the books students choose to read (McCarthey & Moje, 2002; Williams, 2004). Studies also show the effect of self-concept on motivation (particularly engagement and learning in the classroom) and on grades (Choi, 2005; Linnenbrink & Pintrich, 2003). This brief focuses on the racial component of one’s identity and how educators can support students as they develop their identities and leverage it to improve academic outcomes.

PART I: RACIAL AND ACADEMIC IDENTITY

Identity is essentially the answer to the question “who am I?” A person constructs his or her identity throughout life. It is comprised of religion, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, economic background, and a host of other factors. In identity theory, an identity is “the categorization of the self as an occupant of a role and an incorporation of the meanings and expectations associated with that role and its performance” (Stets & Burke, 2000).

Many factors influence the ways in which adolescents view themselves (Fairbanks & Broughton, 2003). The cultural, ethnic, and racial backgrounds of students play an integral role in their beliefs, practices, and expectations for education (Boykin & Toms, 1985). Aspects of an academic identity and an academic self-concept are strongly related to and have an effect on the academic performance of students. Awareness of race and the ways in which structural/institutional racism affects students of color is key to helping them achieve their full academic potential (Howard, 2010).

Academic identity (or academic self concept) has been generally defined as how we see ourselves in an academic domain. Academic identity is a dimension of a larger, global selfconcept (Howard, 2003). Moreover, a student’s academic identity can affect how he or she navigates the school environment. It influences behaviors and choices that students make which affect their educational outcomes. These student outcomes include achievement, academic performance, intellectual engagement, disidentification/ identification, goal orientation/learning goals, educational and occupational aspirations, and motivation.

It is important for educators to have an understanding of how race and culture manifest in education and how race shapes how students see their worlds. On November 13, 2017, the United States Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI) released data from the 2016 Universal Crime Report Hate Crime Statistics program. In 2016, there were 6,063 single-bias incidents reported to law enforcement agencies. Of that number, approximately 58% were motivated by bias due to race, ethnicity, or ancestry. And 9.9% of these issues occurred at a school or college. While not all incidents of bias are classified as hate crimes, they occur much too often to be ignored. This pattern of racial and cultural bias influences how students shape their world view and impacts their concept of self and academic identity.

As educators, we must understand a student’s academic self-concept because it can explain their orientation to school (Plucker & Stocking, 2001). School factors help shape a student’s self-constructed perceptions; for students of color in particular, academic identity is hard to separate from racial and gender identities (Howard, 2003). Leveraging racial identity and racial/cultural awareness may be one way that educators can help meet the varied needs of students. Person environment fit and self-determination theory provide a framework which suggests that certain student needs should be met in order for students to be engaged and motivated in school. As children develop, their needs change and the educational environment (including instructional practices and classroom structure) must shift to meet their needs.

Numerous studies conducted between 1992 and 2001 illuminate how multicultural learning and teaching help foster positive classroom behavior and superior academic achievement for students of color (Allen & Boykin, 1992; Banks, 1993; Ladson-Billings, 1994; Lee, 2001).

PART II: WHAT CAN WE DO?

USE CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE INSTRUCTIONAL PRACTICES Researchers and educators have looked to the role of cultural background, beliefs, and practices in student achievement. In particular, they have stressed culture as a primary link for understanding the academic performance of African American students (e.g., Boykin, 2002; Rogoff, 2003). To enhance the academic outcomes of this population, the curriculum and instructional strategies in public schools should begin to reflect students’ out-of-school cultural experiences (Foster, Lewis, & Onafowora, 2003; Wong & Rowley, 2001). Educators can improve cultural continuity between their students’ home and school experiences by identifying and activating student strengths or situating learning in the lives of students and their families. These strategies can be implemented in a number of ways such as incorporating multicultural books in instructional practices or teaching content by using issues in the students’ community.

LEAD BY EXAMPLE Racial identity has also been deemed an asset in helping students of color negotiate “exposure to risk associated with racial injustice” (Neblett, RivasDrake, & Umana-Taylor, 2012; Zimmerman, Stoddard, Eisman, Caldwell, Aiyer, & Miller, 2013). For students of color, racial identity can serve as a protective and promotive factor of achievement-related outcomes (Oyserman, 2003; Rowley, 1998; Sellers, Caldwell, Schmeelk-Cone, & Zimmerman, 2003; Wong & Rowley, 2001). One way that educators can help their students is to acknowledge the socio-political and historical role that race has played in the United States.

UNDERSTAND THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN MOTIVATION, IDENTITY, AND ACADEMIC OUTCOMES Self-determination theory is based on the idea that people have intrinsic propensities to engage in active, curiosity-based exploration and to integrate new experiences into the self (Hadre & Reeve, 2003; Ryan & Deci, 2002; Skinner & Edge, 2002). This intrinsic motivation and self-regulation leads to positive outcomes such as achievement in school, better decision-making, and goal-setting behaviors. It occurs when certain psychological needs are met: the need for competence, the need for relatedness, and the need for autonomy. Competence refers to feeling capable to complete a task. Relatedness refers to a sense of belonging to the environment. Autonomy is the need for independence and the need to make choices.

Educators can meet the three psychological needs in a number of ways. To satisfy the need for competence, educators can provide students with tasks that they have the skills to complete. Educators can build upon these tasks, as the level of rigor increases, so that students feel capable of completing. To satisfy the need for relatedness, educators can provide students with opportunities to work collaboratively and share their interests and goals with one another. In addition, elevating and utilizing student voice and input increases their sense of relatedness to the environment. To satisfy the need for autonomy, educators can help students by enhancing their opportunities for decision-making and with setting goals. These psychological needs moderate the relationships between risk factors and outcomes for African American students. Students may internalize negative beliefs about their racial group, which may negatively affect their performance in school. This is known as Claude Steele’s notion of stereotype threat (Steele & Aronson, 1995). The process of internalization, a tenet of self-determination theory, occurs because students begin to identify with and internalize messages they receive in their environment. Stigmatized individuals internalize messages and beliefs associated with their group stigma.

When educators meet these needs, students become more engaged and feel more self-determined. By understanding the role of racial identity and academic identity in the lived experiences of students of color, educators can recognize the underlying mechanisms between motivation, engagement, and school outcomes and reduce bias in the classroom and in schools.

Written by Karmen Rouland PhD.

REFERENCES Allen, B. A. and Boykin, A. W. (1992). African American children and the educational process: Alleviating cultural discontinuity through prescriptive pedagogy. School Psychology Review, 21(4), 586-596.

Banks, J. A. (1993). Multicultural education: Historical development, dimension, and practice. Review of Research in Education, 19, 3-49. DOI: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1167339

Bouchey, H. A. & Harter, S. (2005). Reflected appraisals, academic self-perceptions, and math/science performance during early adolescence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97(4), 673-686. DOI: 10.1037/0022-0663.97.4.673

Boykin, A. W. (2002). Integrity-based schooling strategies: Promoting the talent development philosophy. Unpublished manuscript.

Boykin, A. W. & Toms, F. D. (1985). Black child socialization: A conceptual framework. In H. P. McAdoo and J. L. McAdoo (Eds.), Black children: Social, educational, and parental environments (pp. 33-51). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Chavous, T M. (2000). The relationships among racial identity, perceived ethnic fit, and organizational involvement for African American students at a predominantly White university. Journal of Black Psychology, 26(1), 79-100. DOI: 10.1177/0095798400026001005

Choi, N. (2005). Self-efficacy and self-concept as predictors of college students’ academic performance. Psychology in the Schools, 42(2), 197-205. DOI: 10.1002/pits.20048

Fairbanks, C. M., & Broughton, M. A. (2003). Literacy lessons: The convergence of expectations, practices, and classroom culture. Journal of Literacy Research, 34(4), 391-428. DOI:10.1207/s15548430jlr3404_2

Ferguson, R. F. (2003). Teachers’ perceptions and expectations and the Black-White test score gap. Urban Education, 38(4), 460-507. DOI: 10.1177/0042085903038004006

Foster, M., Lewis, J. & Onafowora, L. (2003). Anthropology, culture and research on teaching and learning: Applying what we have learned to improve practice. Teachers College Record,105(2), 261-277.

Hadre, P. L. and Reeve, J. (2003) A motivational model of rural students’ intentions to persist in, versus drop out of, high school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(2), 347-356. DOI: 10.1037/0022-0663.95.2.347

Howard, T. C. (2003). “A tug of war for our minds:” African American high school students’ perceptions of their academic identities and college aspirations. High School Journal, 87(1), 4-17. DOI: 10.1353/hsj.2003.0017

Howard, T. (2010). Why race and culture matter in schools: Closing the achievement gap in America’s classrooms. New York: Teachers College Press.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1994). The dreamkeepers. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishing Co. Lee, C.D. (2001). Is October Brown Chinese? A cultural modeling activity system for underachieving students. American Educational Research Journal, 38(1), 97-142. DOI: 10.3102/00028312038001097

Linnenbrink, E. A., & Pintrich, P. R. (2003). The role of self-efficacy beliefs in student engagement and learning in the classroom. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 19(2), 119-137. DOI: 10.1080/10573560308223

McCarthey, S. J. & Moje, E. B. (2002). Identity matters. Reading Research Quarterly, 37(2), 228-238. DOI: 10.1598/RRQ.37.2.6

Neblett, E. W., Rivas-Drake, D., & Umana-Taylor, A. J. (2012). The promise of racial and ethnic protective factors in promoting ethnic minority youth development. Child DevelopmentPerspectives, 6(3), 295-303. DOI: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00239.x

Oyserman, D., Bybee, D., & Terry, K. (2003). Gendered racial identity and involvement with school. Self and Identity, 2(4), 307-324. DOI: 10.1080/714050250

Plucker, J. A. & Stocking, V. B. (2001). Looking outside and inside: Self-concept development of gifted adolescents. Exceptional Children, 67(4), 535-548. DOI: 10.1177/001440290106700407

Rogoff, B. (2003). The cultural nature of cognitive development. Oxford University Press: New York.

Rowley, S. J., Sellers, R. M., & Chavous, T. M. (1998). The relationship between racial identity and self esteem in African American college and high school students. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(3), 715-724. DOI: 10.1037/0022-3514.74.3.715

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2002). An overview of Self-determination Theory: An organismic-dialectical perspective. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research. 3-33. Rochester, NY: The University of Rochester Press.

Sellers, R. M., Caldwell, C. H., Schmeelk-Cone, K. H., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2003). Racial identity, racial discrimination, perceived stress, and psychological distress among African American young adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44(3), 302 – 317. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1519781

Skinner, E. A., & Edge, K. (2002). Parenting, motivation, and the development of children’s coping. In L. J. Crockett (Ed.), Agency, motivation, and the life course: The Nebaska symposium on motivation, Vol. 48 (pp. 77-143). Lincoln, NE: University Of Nebraska Press.

Steele, C. M. & Aronson, J. (1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(5), 797-811. DOI: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.797

Stets, J. E., & Burke, P. J. (2000). Identity theory and social identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63, 224-237. DOI: 10.2307/2695870.

Williams, B. T. (2004). Heroes, rebels, and victims: Student identities in literacy narratives. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 47(4), 342-345. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40014780 .

Wong, C. A. & Rowley, S. J. (2001). The schooling of ethnic minority children: Commentary. Educational Pscyhologist, 36(1), 57-66. DOI: 10.1207/S15326985EP3601_6

Zimmerman, M. A., Stoddard, S. A., Eisman, A. B., Caldwell, C. H., Aiyer, S. M., Miller, A. (2013). Adolescent resilience: Promotive factors that inform prevention. Child Development Perspectives, 7(4), 215-220. DOI: 10.1111/cdep.12042.

Join Our Mailing List

Receive monthly updates on news and events. Learn about best practices. Be the first to hear about our next free webinar!

Home — Essay Samples — Life — About Myself — My Racial Autobiography: Understanding Identity and Fighting for Justice

My Racial Autobiography: Understanding Identity and Fighting for Justice

- Categories: About Myself National Identity

About this sample

Words: 571 |

Published: Feb 7, 2024

Words: 571 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Table of contents

Family background and cultural identity, racial identity development, personal experiences with racism, intersectionality, community involvement and activism.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Life Sociology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1184 words

2 pages / 1069 words

2 pages / 732 words

1 pages / 514 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on About Myself

There are moments in life when the act of opening a door becomes an invitation to the extraordinary. As I stood before that unassuming door, the anticipation of what lay on the other side ignited my imagination. It was a door [...]

The ability for one to identify self in the immediate environment is an essential component. My identity can be explained in my personality and the continuous interaction in the environments I have been since I was young. [...]

Childhood During my early years, I had the opportunity to explore and discover the world around me. As a child, I was filled with curiosity and wonder, always eager to learn and try new things. Whether it was exploring the [...]

There is that one time when you come to realize that, your whole perception of life has been an illusion, and that discernment changes forever. That time when you stop being a child and grow up. The shift comes in bits and [...]

In this essay I am going to explain my family history. It is almost a tradition to go into the army, or into different areas related to that, like the Marines, in my family. My uncle, my mother’s father, my great grandfather, [...]

It was when my father taught me the game of “Cashflow 101” by Robert Kiyosaki, author of Rich Dad, Poor Dad, that I developed a keen interest in the world of finance. Through the game, I was able to better understand the [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Ethnic and Racial Identity in Adolescence: Implications for Psychosocial, Academic, and Health Outcomes

Deborah rivas-drake.

Brown University

Carol Markstrom

West Virginia University

University of Minnesota

Richard M. Lee

Adriana j. umaña-taylor.

Arizona State University

Tiffany Yip

Fordham University

Eleanor K. Seaton

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Stephen Quintana

University of Wisconsin

Seth J. Schwartz

University of Miami

Sabine French

University of Illinois at Chicago

The construction of an ethnic or racial identity is considered an important developmental milestone for youth of color. This review summarizes research on links between ethnic and racial identity (ERI) with psychosocial, academic, and health risk outcomes among ethnic minority adolescents. With notable exceptions, aspects of ERI are generally associated with adaptive outcomes. ERI are generally beneficial for African American adolescents’ adjustment across all three domains, whereas the evidence is somewhat mixed for Latino and American Indian youth. There is a dearth of research for academic and health risk outcomes among Asian American and Pacific Islander adolescents. The review concludes with suggestions for future research on ERI among minority youth.

The U.S. youth population is in the midst of a remarkable transformation. Currently, ethnic minorities constitute the majority of all U.S. births and more than 40% of American youth under age 18 ( U.S. Census, 2012 ). As the nation’s populace continues to diversify, it is becoming increasingly necessary to fully explicate the role of ethnicity and race in normative developmental processes among young people. The construction of an ethnic or racial identity is thought to be one important means by which ethnicity and race influence normative development and promote positive youth adjustment (e.g., Neblett, Rivas-Drake, & Umaña-Taylor, 2012 ; Williams, Tolan, Durkee, Francois, & Anderson, 2012 ). For example, a recent meta-analysis suggests that an achieved, positive ethnic identity is favorably associated with self-esteem and negatively associated with depressive symptoms among ethnic minority individuals ( Smith & Silva, 2011 ). Empirical research also suggests that some components of ethnic and racial identity (ERI) can buffer the deleterious consequences of adverse life events, such as racial and ethnic discrimination on internalizing symptoms and other negative outcomes ( Galliher, Jones, & Dahl, 2011 ; Rivas-Drake, Hughes, & Way, 2008 ; Sellers, Copeland-Linder, Martin, & Lewis, 2006 ).

The purpose of this article is to provide a narrative review of the existing literature on how racial and ethnic identity are associated with psychological, academic, and health outcomes among ethnic minority adolescents. Although there is broad consensus that identity processes are generally pertinent to adolescence, diverse theoretical traditions posit the particular importance of adolescence in the construction of ethnic and racial identities, concomitant with increased experiences of discrimination ( Greene, Way, & Pahl, 2006 ) and advances in social perspective-taking ability ( Quintana, 1994 , 1999 ) during this period of life vis- à-vis childhood (cf. Umaña-Taylor et al., in press). For instance, Quintana (1994) argued that whereas children form concepts of ethnicity and race, understand their (presumed) literal meanings, and observe their concrete significance in everyday life, adolescents’ notions of ethnicity and race are more abstract and complex. Quintana’s model posits that adolescence is marked by an increased group consciousness perspective of ERI that underlies implications for adjustment, as youth make meaning of their ethnic or racial experiences relative to those of other individuals. In this review, we sought to unpack the degree to which the presumed importance of ERI for adjustment in adolescence is borne out in the empirical literature. As will be discussed, the plethora of studies examining ERI in adolescence supports the notion that it is a period of increased meaning-making around the complexities of ethnic and racial group membership and, consequently, potentially increased significance for adjustment.

Identities linked to ethnicity or race can be developed based on cultural background (e.g., values, traditions) or specific experiences (e.g., racial discrimination) resulting from self-perceived ethnic or racial group membership, or both ( Helms, Jernigan, & Mascher, 2005 ). To help clarify our terminology, we acknowledge the long-standing controversy regarding the use of ethnicity and race in the empirical literature (e.g., Cokley, 2007 ; Helms, 2007 ). Phinney (1996) suggested referring to ethnic and racial groups collectively as ethnic groups due to concerns that using the term race often implies a biological foundation. However, Helms and Talleyrand (1997) suggested that race be retained and limit the term ethnicity to refer to cultural components. With increasing research on Latinos, who are typically defined as an ethnic rather than a racial group, using the term race alone to refer to samples that include Hispanics or Latinos may be problematic. In those mixed samples including Latinos, researchers have noted the use of either ethnic or a combination of ethnic and racial to refer to their samples and their identity formation ( Byrd, 2012 ; Cross & Cross, 2008 ). Many scholars tend to use some combination of ethnicity and race when describing multiple ethnic and racial groups, except when there is a narrow focus on a few groups that have been historically considered racial groups (e.g., Black vs. White).

A number of scholars have also discussed the problem of conflating ethnicity and race with little regard for the social structures in which diverse ethnic and racial group members live ( Markus, 2008 ). Briefly, race indicates power and connotes the ongoing hierarchy in which one group considers other groups as different and inferior ( Markus, 2008 ). Racial differences may indicate differences in societal worth that dominant group members impose on subordinate groups, which are accompanied by stereotypes and prejudicial notions that minority group members often resist ( Markus, 2008 ; Omi & Winant, 1994 ). Yet, ethnicity emphasizes differences in meanings, values, and cultural practices generalized to specific groups ( Markus, 2008 ; Omi & Winant, 1994 ). Ethnic differences may refer to differences in ways of living that derive from association with specific subordinate groups and are often claimed, appreciated and embraced by subordinate group members. We concur with Markus (2008) who argued:

The social distinction of race and ethnicity are inventions—race and ethnicity are alike in many respects. Both race and ethnicity are dynamic sets of ideas (e.g., meanings, values, goals, images, associations) and practices (e.g., meaningful actions, both formal and routine) that people create to distinguish groups and organize their own communities. (p. 654)