Job Loss and Unemployment Stress

Dealing with uncertainty, elder scams and senior fraud abuse, stress relief guide, social support for stress relief, 12 ways to reduce stress with music, surviving tough times by building resilience.

- Stress Management: How to Reduce and Relieve Stress

- Online Therapy: Is it Right for You?

- Mental Health

- Health & Wellness

- Children & Family

- Relationships

Are you or someone you know in crisis?

- Bipolar Disorder

- Eating Disorders

- Grief & Loss

- Personality Disorders

- PTSD & Trauma

- Schizophrenia

- Therapy & Medication

- Exercise & Fitness

- Healthy Eating

- Well-being & Happiness

- Weight Loss

- Work & Career

- Illness & Disability

- Heart Health

- Childhood Issues

- Learning Disabilities

- Family Caregiving

- Teen Issues

- Communication

- Emotional Intelligence

- Love & Friendship

- Domestic Abuse

- Healthy Aging

- Aging Issues

- Alzheimer’s Disease & Dementia

- Senior Housing

- End of Life

- Meet Our Team

Understanding financial stress

Effects of financial stress on your health, tip 1: talk to someone, tip 2: take inventory of your finances, tip 3: make a plan—and stick to it, tip 4: create a monthly budget, tip 5: manage your overall stress, coping with financial stress.

Feeling overwhelmed by money worries? Whatever your circumstances, there are ways to get through these tough economic times, ease stress and anxiety, and regain control of your finances.

If you’re worried about money, you’re not alone. Many of us, from all over the world and from all walks of life, are having to deal with financial stress and uncertainty at this difficult time. Whether your problems stem from a loss of work, escalating debt, unexpected expenses, or a combination of factors, financial worry is one of the most common stressors in modern life. Even before the global coronavirus pandemic and resulting economic fallout, an American Psychological Association (APA) study found that 72% of Americans feel stressed about money at least some of the time. The recent economic difficulties mean that even more of us are now facing financial struggles and hardship.

Like any source of overwhelming stress, financial problems can take a huge toll on your mental and physical health, your relationships, and your overall quality of life. Feeling beaten down by money worries can adversely impact your sleep, self-esteem, and energy levels. It can leave you feeling angry, ashamed, or fearful, fuel tension and arguments with those closest to you, exacerbate pain and mood swings, and even increase your risk of depression and anxiety. You may resort to unhealthy coping mechanisms, such as drinking, abusing drugs, or gambling to try to escape your worries. In the worst circumstances, financial stress can even prompt suicidal thoughts or actions. But no matter how hopeless your situation seems, there is help available. By tackling your money problems head on, you can find a way through the financial quagmire, ease your stress levels, and regain control of your finances—and your life.

While we all know deep down there are many more important things in life than money, when you’re struggling financially fear and stress can take over your world. It can damage your self-esteem, make you feel flawed, and fill you with a sense of despair. When financial stress becomes overwhelming, your mind, body, and social life can pay a heavy price.

[Read: Stress Symptoms, Signs, and Causes]

Financial stress can lead to:

Insomnia or other sleep difficulties. Nothing will keep you tossing and turning at night more than worrying about unpaid bills or a loss of income.

Weight gain (or loss). Stress can disrupt your appetite, causing you to anxiously overeat or skip meals to save money.

Depression. Living under the cloud of money problems can leave anyone feeling down, hopeless, and struggling to concentrate or make decisions. According to a study at the University of Nottingham in the UK, people who struggle with debt are more than twice as likely to suffer from depression .

Anxiety. Money can be a safety net; without it, you may feel vulnerable and anxious. And all the worrying about unpaid bills or loss of income can trigger anxiety symptoms such as a pounding heartbeat, sweating, shaking, or even panic attacks.

Relationship difficulties. Money is often cited as the most common issue couples argue about. Left unchecked, financial stress can make you angry and irritable, cause a loss of interest in sex, and wear away at the foundations of even the strongest relationships .

Social withdrawal. Financial worries can clip your wings and cause you to withdraw from friends, curtail your social life, and retreat into your shell—which will only make your stress worse.

Physical ailments such as headaches, gastrointestinal problems, diabetes, high blood pressure , and heart disease. In countries without free healthcare, money worries may also cause you to delay or skip seeing a doctor for fear of incurring additional expenses.

Unhealthy coping methods , such as drinking too much , abusing prescription or illegal drugs, gambling, or overeating. Money worries can even lead to self-harm or thoughts of suicide.

If you are feeling suicidal…

Your money problems may seem overwhelming and permanent right now. But with time, things will get better and your outlook will change, especially if you get help. There are many people who want to support you during this difficult time, so please reach out!

Read Are You Feeling Suicidal? , call 1-800-273-TALK in the U.S., or find a helpline in your country at IASP or Suicide.org .

The vicious cycle of poor financial health and poor mental health

A number of studies have demonstrated a cyclical link between financial worries and mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, and substance abuse.

Financial problems adversely impact your mental health. The stress of debt or other financial issues leaves you feeling depressed or anxious.

The decline in your mental health makes it harder to manage money. You may find it harder to concentrate or lack the energy to tackle a mounting pile of bills. Or you may lose income by taking time off work due to anxiety or depression.

These difficulties managing money lead to more financial problems and worsening mental health problems, and so on. You become trapped in a downward spiral of increasing money problems and declining mental health.

No matter how bleak your situation may seem at the moment, there is a way out. These strategies can help you to break the cycle, ease the stress of money problems, and find stability again.

When you’re facing money problems, there’s often a strong temptation to bottle everything up and try to go it alone. Many of us even consider money a taboo subject, one not to be discussed with others. You may feel awkward about disclosing the amount you earn or spend, feel shame about any financial mistakes you’ve made, or embarrassed about not being able to provide for your family. But bottling things up will only make your financial stress worse. In the current economy, where many people are struggling through no fault of their own, you’ll likely find others are far more understanding of your problems.

[Read: Social Support for Stress Relief]

Not only is talking face-to-face with a trusted friend or loved one a proven means of stress relief, but speaking openly about your financial problems can also help you put things in perspective. Keeping money worries to yourself only amplifies them until they seem insurmountable. The simple act of expressing your problems to someone you trust can make them seem far less intimidating.

- The person you talk to doesn’t have to be able to fix your problems or offer financial help.

- To ease your burden, they just need to be willing to talk things out without judging or criticizing.

- Be honest about what you’re going through and the emotions you’re experiencing.

- Talking over your worries can help you make sense of what you’re facing and your friend or loved one may even be able to come up with solutions that you hadn’t thought of alone.

Getting professional advice

Depending on where you live, there are a number of organizations that offer free counseling on dealing with financial problems, whether it’s managing debt, creating and sticking to a budget, finding work, communicating with creditors, or claiming benefits or financial assistance. (See the “Get more help” section below for links).

Whether or not you have a friend or loved one to talk to for emotional support, getting practical advice from an expert is always a good idea. Reaching out is not a sign of weakness and it doesn’t mean that you’ve somehow failed as a provider, parent, or spouse. It just means that you’re wise enough to recognize your financial situation is causing you stress and needs addressing.

Speak to a Licensed Therapist

BetterHelp is an online therapy service that matches you to licensed, accredited therapists who can help with depression, anxiety, relationships, and more. Take the assessment and get matched with a therapist in as little as 48 hours.

Opening up to your family

Financial problems tend to impact the whole family and enlisting your loved ones’ support can be crucial in turning things around. Even if you take pride in being self-sufficient, keep your family up to date on your financial situation and how they can help you save money.

Let them express their concerns. Your loved ones are probably worried—about both you and the financial stability of your family unit. Listen to their concerns and allow them to offer suggestions on how to resolve the financial problems you’re facing.

Make time for (inexpensive) family fun. Set aside regular time where you can enjoy each other’s company, let off steam, and forget about your financial worries. Walking in the park, playing games, or exercising together doesn’t have to cost money but it can help ease stress and keep the whole family positive.

If you’re struggling to make ends meet, you may think you can ease your stress by leaving bills unopened, avoiding phone calls from creditors, or ignoring bank and credit card statements. But denying the reality of your situation will only make things worse in the long run. The first step to devising a plan to solve your money problems is to detail your income, debt, and spending over the course of at least one month.

A number of websites and smartphone apps can help you keep track of your finances moving forward or you can work backwards by gathering receipts and examining bank and credit card statements. Obviously, some money difficulties are easier to solve than others, but by taking inventory of your finances you’ll have a much clearer idea of where you stand. And as daunting or painful as the process may seem, tracking your finances in detail can also help you start to regain a much-needed sense of control over your situation.

Include every source of income. In addition to any salary, include bonuses, benefits, alimony, child support, or any interest you receive.

Keep track of ALL your spending. When you’re faced with a pile of past-due bills and mounting debt, buying a coffee on the way to work may seem like an irrelevant expense. But seemingly small expenses can mount up over time, so keep track of everything. Understanding exactly how you spend your money is key to budgeting and devising a plan to address your financial problems.

List your debts. Include past-due bills, late fees, and list minimum payments due as well as any money you owe to family or friends.

Identify spending patterns and triggers. Does boredom or a stressful day at work cause you to head to the mall or start online shopping? When the kids are acting out, do you keep them quiet with expensive restaurant or takeout meals, rather than cooking at home ? Once you’re aware of your triggers you can find healthier ways of coping with them than resorting to “retail therapy”.

Look to make small changes. Spending money on things like a morning newspaper, lunchtime sandwich, or break-time cigarettes can add up to a significant monthly outlay. While it may be unreasonable to deny yourself every small pleasure, cutting down on nonessential spending and finding small ways to reduce your daily expenditure can really help to free up extra cash to pay off bills.

Eliminate impulse spending. Ever seen something online or in a shop window that you just had to buy? Impulsive buying can wreck your budget and max out your credit cards. To break the habit, try making a rule that you’ll wait a week before making any new purchase.

Go easy on yourself. As you review your debt and spending habits, remember that anyone can get into financial difficulties, especially at times like this . Don’t use this as an excuse to punish yourself for any perceived financial mistakes. Give yourself a break and focus on the aspects you can control as you look to move forward.

When your financial problems go beyond money

Sometimes, the causes for your financial difficulties may lie elsewhere. For example, money troubles can stem from problem gambling , fraud abuse , or a mental health issue, such as overspending during a bipolar manic episode .

To prevent the same financial problems recurring, it’s imperative you address both the underlying issue and the money troubles it’s created in your life.

Just as financial stress can be caused by a wide range of different money problems, so there are an equally wide range of possible solutions. The plan to address your specific problem could be to live within a tighter budget, lower the interest rate on your credit card debt, curb your online spending, seek government benefits, declare bankruptcy, or to find a new job or additional source of income.

If you’ve taken inventory of your financial situation, eliminated discretionary and impulse spending, and your outgoings still exceed your income, there are essentially three choices open to you: increase your income, lower your spending, or both. How you go about achieving any of those goals will require making a plan and following through on it.

- Identify your financial problem. Having taken inventory, you should be able to clearly identify the financial problem you’re facing. It may be that you have too much credit card debt, not enough income, or you overspend on unnecessary purchases when you feel stressed or anxious. Or perhaps, it’s a combination of problems. Make a separate plan for each one.

- Devise a solution. Brainstorm ideas with your family or a trusted friend, or consult a free financial counseling service. You may decide that talking to credit card companies and requesting a lower interest rate would help solve your problem. Or maybe you need to restructure your debt, eliminate your car payment, downsize your home, or talk to your boss about working overtime.

- Put your plan into action. Be specific about how you can follow through on the solutions you’ve devised. Perhaps that means cutting up credit cards, networking for a new job , registering at a local food bank, or selling things on eBay to pay off bills, for example.

- Monitor your progress. As we’ve all experienced recently, events that impact your financial health can happen quickly, so it’s important to regularly review your plan. Are some aspects working better than others? Do changes in interest rates, your monthly expenses, or your hourly wage, for example, mean you should revise your plan?

- Don’t get derailed by setbacks. We’re all human and no matter how tight your plan, you may stray from your goal or something unexpected could happen to derail you. Don’t beat yourself up, but get back on track as soon as possible.

The more detailed you can make your plan, the less powerless you’ll feel over your financial situation.

Whatever your plan to relieve your financial problems, setting and following a monthly budget can help keep you on track and regain your sense of control.

- Include everyday expenses in your budget, such as groceries and the cost of traveling to work, as well as monthly rent, mortgage, and utility bills.

- For items that you pay annually, such as car insurance or property tax, divide them by 12 so you can set aside money each month.

- If possible, try to factor in unexpected expenses, such as a medical co-pay or prescription charge if you fall sick, or the cost of home or car repairs.

- Set up automatic payments wherever possible to help ensure bills are paid on time and you avoid late payments and interest rate hikes.

- Prioritize your spending. If you’re having trouble covering your expenses each month, it can help to prioritize where your money goes first. For example, feeding and housing yourself and your family and keeping the power on are necessities. Paying your credit card isn’t—even if you’re behind on your payments and have debt collection companies harassing you.

- Keep looking for ways to save money. Most of us can find something in our budget that we can eliminate to help make ends meet. Regularly review your budget and look for ways to trim expenses.

- Enlist support from your spouse, partner, or kids. Make sure everyone in your household is pulling in the same direction and understands the financial goals you’re working towards.

Resolving financial problems tends to involve small steps that reap rewards over time. In the current economic climate, it’s unlikely your financial difficulties will disappear overnight. But that doesn’t mean you can’t take steps right away to ease your stress levels and find the energy and peace of mind to better deal with challenges in the long-term.

[Read: Stress Management]

Get moving. Even a little regular exercise can help ease stress, boost your mood and energy, and improve your self-esteem. Aim for 30 minutes on most days, broken up into short 10-minute bursts if that’s easier.

Practice a relaxation technique. Take time to relax each day and give your mind a break from the constant worrying. Meditating , breathing exercises, or other relaxation techniques are excellent ways to relieve stress and restore some balance to your life.

Don’t skimp on sleep. Feeling tired will only increase your stress and negative thought patterns. Finding ways to improve your sleep during this difficult time will help both your mind and body.

Boost your self-esteem. Rightly or wrongly, experiencing financial problems can cause you to feel like a failure and impact your self-esteem. But there are plenty of other, more rewarding ways to improve your sense of self-worth. Even when you’re struggling yourself, helping others by volunteering can increase your confidence and ease stress, anger, and anxiety—not to mention aid a worthy cause. Or you could spend time in nature, learn a new skill, or enjoy the company of people who appreciate you for who you are, rather than for your bank balance.

Eat healthy food. A healthy diet rich in fruit, vegetables, and omega-3s can help support your mood and improve your energy and outlook. And you don’t have to spend a fortune; there are ways to eat well on a budget .

Be grateful for the good things in your life. When you’re plagued by money worries and financial uncertainty , it’s easy to focus all your attention on the negatives. While you don’t have to ignore reality and pretend everything’s fine, you can take a moment to appreciate a close relationship, the beauty of a sunset, or the love of a pet, for example. It can give your mind a break from the constant worrying, help boost your mood, and ease your stress.

Find financial resources

Find U.S. Government Services and Information including How to Get Out of Debt , Unemployment Help , and Getting Help with Living Expenses . Or call 1-844-872-4681. (USA gov)

Get help with debt and housing problems from Citizens Advice , contact a free debt service at National Debtline or Stepchange , or seek free financial advice from the government’s Money Advice Service .

Find Government Services , get free Financial Counselling or call the National Debt Helpline at 1800 007 007.

Find government services and information for Managing Debt and Benefits .

More Information

- Managing Job Loss and Financial Stress - Helping yourself and your family cope with stress and financial worries following job loss. (University of Hawaii)

- Managing Debt - Steps you can take to deal with debt. (Federal Trade Commission)

- Managing money and budgeting - Tips for creating a family budget. (raisingchildren.net.au)

- Make a Budget - Simple worksheet to help you create a budget. (Federal Trade Commission)

- Money Stress Weighing on Americans’ Health - Details of the 2015 Stress in America: Paying with Our Health survey from the American Psychological Association. (APA)

- Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders. (2013). In Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders . American Psychiatric Association. Link

- Inc, Gallup. “The U.S. Healthcare Cost Crisis.” Gallup.com. Accessed November 16, 2021. Link

- Anderson, Norman B, Cynthia D Belar, Steven J Breckler, Katherine C Nordal, David W Ballard, Lynn F Bufka, Luana Bossolo, Sophie Bethune, Angel Brownawell, and Katelynn Wiggins. Stress in America: Paying with our Health. “AMERICAN PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION,” n.d., 23. Link

- Ramsey Solutions. “Money, Marriage, and Communication.” Accessed November 16, 2021. Link

- “At What Costs? Student Loan Debt, Debt Stress, and Racially/Ethnically Diverse College Students’ Perceived Health. – PsycNET.” Accessed November 16, 2021. Link

- Richardson, Thomas, Peter Elliott, and Ronald Roberts. “The Relationship between Personal Unsecured Debt and Mental and Physical Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Clinical Psychology Review 33, no. 8 (December 1, 2013): 1148–62. Link

- Warth, Jacqueline, Marie-Therese Puth, Judith Tillmann, Johannes Porz, Ulrike Zier, Klaus Weckbecker, and Eva Münster. “Over-Indebtedness and Its Association with Sleep and Sleep Medication Use.” BMC Public Health 19, no. 1 (July 17, 2019): 957. Link

- Saleh, Dalia, Nathalie Camart, Fouad Sbeira, and Lucia Romo. “Can We Learn to Manage Stress? A Randomized Controlled Trial Carried out on University Students.” PLOS ONE 13, no. 9 (September 5, 2018): e0200997. Link

- “Stress, Social Support, and the Buffering Hypothesis. – PsycNET.” Accessed November 15, 2021. Link

- Salmon, P. “Effects of Physical Exercise on Anxiety, Depression, and Sensitivity to Stress: A Unifying Theory.” Clinical Psychology Review 21, no. 1 (February 2001): 33–61. Link

- Toussaint, Loren, Quang Anh Nguyen, Claire Roettger, Kiara Dixon, Martin Offenbächer, Niko Kohls, Jameson Hirsch, and Fuschia Sirois. “Effectiveness of Progressive Muscle Relaxation, Deep Breathing, and Guided Imagery in Promoting Psychological and Physiological States of Relaxation.” Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2021 (July 3, 2021): e5924040. Link

More in Stress

Coping with the stress of losing a job

How to cope with events in life outside your control

Preventing and dealing with financial exploitation

Quick tips for when you’re short on time

Using close relationships to manage stress and improve well-being

Fill your life with music that reduces daily stress

Tips for overcoming adversity

Stress Management

How to reduce, prevent, and relieve stress

Professional therapy, done online

BetterHelp makes starting therapy easy. Take the assessment and get matched with a professional, licensed therapist.

Help us help others

Millions of readers rely on HelpGuide.org for free, evidence-based resources to understand and navigate mental health challenges. Please donate today to help us save, support, and change lives.

How financial stress can affect your mental health and 5 things that can help

Associate Professor, School of Psychological Science, and Director, Emotional Wellbeing Lab, The University of Western Australia

Disclosure statement

Kristin Naragon-Gainey receives funding from the National Institutes of Health.

University of Western Australia provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Financial stress is affecting us in many different ways. Some people are struggling to pay bills, feed the family, or maintain a place to live. Others are meeting their basic needs but are dipping into their savings for extras.

Financial stress is increasing and, understandably, is causing some distress. In recent months, Lifeline has seen a rise in the number of calls about financial difficulties.

But understanding and finding ways to reduce our financial stress – and its emotional impact on us – can help make this challenging time a bit easier.

Read more: What's taking the biggest toll on our mental health? Disconnection, financial stress and long waits for care

What is financial stress?

If you’re finding it difficult to meet your current expenses or are worried about your current or future finances, you’re under financial stress . Like other types of stress, financial stress has two components:

objective financial difficulty, where you don’t have enough funds to cover necessary expenses or debts

subjective perceptions about your current or future finances, leading to worry and distress.

These two are related. But someone can have trouble meeting their expenses, view this as acceptable, and not be overly worried. Alternatively, someone may be reasonably financially secure but still feel quite stressed about their finances.

Read more: Stress is a health hazard. But a supportive circle of friends can help undo the damaging effects on your DNA

Why are we feeling it?

There is a broad range of factors that can influence your current level of financial stress. These include contextual and personal ones.

Contextual factors are societal-level influences on the current financial landscape. These include rates of economic growth, market performance, governmental and political policy, and distribution of wealth. These factors may vary across cultures and countries.

Personal factors contributing to stress are unique to each person. For example, demographic characteristics such as age, gender, education and ethnic group may influence someone’s access to financial resources.

Other personal factors that can affect financial stress are financial literacy and practices, personality traits that influence behaviour and perceptions, and major life events with financial implications (such as marriage, having a child, or retiring).

Read more: Centrelink debt debacle is bad policy for mental health

The health impacts can be severe

High levels of financial stress can impact people’s wellbeing, raising levels of psychological distress, anxiety and depression.

A review found clear evidence for a link between financial stress and depression, and that the risk for depression was greatest for people on low incomes.

A large survey of adults in the United States also found that greater financial worries were associated with more psychological distress. This was especially the case for people who were unmarried, unemployed, had lower income levels and who were renters.

So people who are more vulnerable financially – in an objective sense – are also most likely to experience negative psychological effects from financial stress.

However, the perception of your financial situation matters here too. In one study of older adults, including Australians, it was not just someone’s financial situation that was linked to their wellbeing, but also how satisfied people were with their wealth.

Severe financial stressors, such as being forced to sell your home if unable to meet mortgage payments, can affect both psychological and physical health.

Read more: 'We lost the house, we lost everything': what dealing with financial stress looks like

What can I do about it?

While we can’t change the broader financial landscape or some aspects of our financial situation, there are some simple ways to help reduce financial stress and its impacts.

1. Take small steps

Try to identify elements of your finances you can improve and act on some of them, even if they are small steps. This may include creating and following a budget, cutting some extra costs, applying for available financial assistance, getting quotes for more affordable utilities or insurance, or contemplating a career change. Even little changes can improve your financial state over time. Taking action in a difficult situation can improve wellbeing by giving you a greater sense of agency.

2. Check your take on the situation

Examine your perspective. Are you often seeing the negative aspects of your situation but ignoring the positive ones? Are you worrying a lot about very unlikely catastrophes far off in the future? It’s worth checking whether your perceptions about your financial situation are accurate and balanced.

3. Don’t be too hard on yourself

Your financial state does not reflect your value as a person, and over-identifying with your financial status can lead to further stress. Financial difficulties are the result of many factors, only some of which are under your control. Reminding yourself that your finances do not define you as a person can reduce feelings of sadness, shame or guilt.

4. Take care of yourself

It’s draining dealing with ongoing financial stress. So focus on self-care and coping strategies that have helped you with past stressors. This may mean taking some time out to relax, deep breathing or meditation, talking with others and doing some things for fun. Giving yourself permission to take this time can improve your mood, perspective and wellbeing.

5. Ask for help

If you are struggling financially or psychologically, seek help. This may take the form of financial advice or assistance to reduce financial difficulties. If you notice yourself feeling persistently down, anxious, or hopeless, reach out to friends or family and get help from a mental health professional.

If this article has raised issues for you, or if you’re concerned about someone you know, call Lifeline on 13 11 14.

- Mental health

- Cost of living

- Financial stress

- Mental wellbeing

- Cost of living crisis

Biocloud Project Manager - Australian Biocommons

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

Deputy Editor - Technology

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Financial Stress: How to Cope

Elizabeth Scott, PhD is an author, workshop leader, educator, and award-winning blogger on stress management, positive psychology, relationships, and emotional wellbeing.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Elizabeth-Scott-MS-660-695e2294b1844efda01d7a29da7b64c7.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Verywell / Laura Porter

Understanding Financial Stress

Impact on your health, tips for coping, overcoming financial stress.

If you're worried about money, you're not alone. Money is a common source of stress for American adults. In fact, according to the American Psychological Association (APA), 72% of adults report feeling stressed about money, whether it's worrying about paying rent or feeling bogged down by debt. This is pretty significant given financial stress is linked to so many health issues.

Press Play for Advice On Dealing With Money Issues

This episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast shares what to do when financial stress is impacting your mental health. Click below to listen now.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts / Amazon Music

Financial stress is emotional tension that is specifically related to money. Anyone can experience financial stress, but financial stress may occur more often in households with low incomes. Stress can result from not making enough money to meet your needs such as paying rent, paying the bills, and buying groceries.

People with less income might experience additional stress due to their jobs. Their jobs might lack flexibility when it comes to taking time off. They might work in unsafe environments , but they are afraid to leave because they won't be able to support themselves financially while they look for another job.

People with low incomes may not have access to resources to manage their financial stress, either, such as health insurance to receive mental health treatment .

Most people stress about money from time to time. But financial stress can become problematic if it disrupts your everyday life. For instance, you might find you can't focus on or enjoy other parts of your life because your money-related stress is causing you to worry so much.

If your financial stress is severe, you will experience negative effects on your mental health and potentially even your physical health. Financial stress can lead to anxiety , depression , behavioral changes like withdrawing from social activities, or physical symptoms like stomachaches or headaches.

If you experience any side effects related to your financial stress, be sure to talk to a healthcare professional.

Although any stress can take a toll on your health, stress related to financial issues can be especially toxic. Financial stress can lead to:

- Delayed health care : With less money in the budget, people who are already under financial stress tend to cut corners in areas they shouldn't, like health care. According to Gallup's annual Health and Healthcare poll , 29% of American adults held off seeking medical care in 2018 because of cost. Though this tactic may seem like a good way to keep costs down, delaying medical care can actually lead to worse health outcomes and higher costs, both of which can lead to more stress.

- Poor mental health : In many instances, the link between mental and financial health is cyclical—poor financial health can lead to poor mental health, which leads to increasingly poor financial health, and so on. For years, studies have shown that people in debt have higher rates of mental health issues like depression and anxiety than those who are debt-free.

- Poor physical health : Ongoing stress about money has been linked to headaches, stomachaches, migraines, heart disease, diabetes, sleep problems, and more. When we are constantly stressed, our bodies don't have time to recover. Our immune systems are left susceptible to illnesses—this includes colds and viruses. If you already have a chronic medical condition, you may experience flare-ups of your symptoms.

- Unhealthy coping behaviors : Financial stress can cause you to engage in a variety of unhealthy behaviors, from overeating to alcohol and drug use . According to an APA survey published in 2014, 33% of Americans reported eating unhealthy foods or eating too much to deal with stress.

Learning to cope with financial stress and effectively manage your financial situation can help you feel more in control of your life, reduce your stress, and build a more secure future. Try some of the following tips to get started:

- Create extra sources of income . If you're feeling stressed about finances, you likely already feel you need more money in your budget. But knowing how to increase your financial holdings without creating significant stress for yourself can be tricky, too. Thankfully, there are several ways to boost your income and relieve your stress.

- Declutter your budget . Since life is rarely constant, regular budget checkups are essential to improving your financial health. Take control of your finances by setting aside some time to schedule, organize, and declutter all of the money coming in and out of your bank account. The more control you have, the less stress you will feel.

- Don't forget general stress management . As you work on improving your financial situation, you can reduce stress by practicing stress-reducing techniques and making other changes to create a low-stress lifestyle. Eating a nutritious diet , getting enough sleep every night, and doing some form of physical exercise are linked with reducing stress levels. You can also try mindfulness techniques like deep breathing and yoga to ease any anxiety.

- Understand the debt cycle . Understanding debt is the first step to getting yourself out of it. One study found that you may be able to pay off your debt more quickly by paying off one account at a time and by starting with your lowest debts first. Do your research and pay attention to interests rates. It's advisable to first pay off the debt that has the largest interest rate to avoid paying higher costs over time.

It might be impossible to fix your financial problems overnight, but you can start planning for success right away. Remember, the stress you experience isn't only a result of your financial situation—you can ease some of your anxiety by taking care of yourself.

Take Stock of Your Finances

Make a list of the financial struggles that most concern you. Take baby steps to tackle each problem one by one so you don't overwhelm yourself.

Write down what you can start doing today or this week that can get you on track to financial stability. Try making a budget plan, only spending on necessities for a week or a month.

You can also try tracking your spending. Keep a daily or weekly list of what you spend money on, and see where you can spend less.

You might seek professional assistance to help you with your finances. For instance, you can research student loan forgiveness programs and income-based repayment programs that may create more manageable payments for your debt.

If you can't pay your bills, try calling your bank, utility company, or credit card company to explain your situation—oftentimes, they can set up a payment plan that works for you.

Reach Out for Support

Try reaching out for support from your family and friends to help reduce stress. You might try attending a support group for people who are struggling with financial stress, too. Remember, you're not alone. You can develop a system of trusted friends and family to help you stay optimistic about your finances.

In some cases, you may even choose to seek professional help from a mental health care provider. All options for support are valid.

Engage in Self-Care

Maintaining a healthy lifestyle is important to help you manage stress. Try to exercise for 30 minutes a day—move your body in whatever way feels good for you. This improves your mental and physical health. Walking is a great way to get a workout in and relieve stress at the same time.

Make time to relax . Though your financial stress can overwhelm you, remember that there are resources to help you manage your stress and your finances. Take time to unwind, meditate , enjoy a fun activity , and connect with others.

Links and Resources

- Ask a Therapist: How Do I Tackle my Debt and My Anxiety

- How Your Money Affects Your Mental Health

- 4 Simple Ways to Relieve Money Stress

Tran AGTT, Mintert JS, Llamas JD, Lam CK. At what costs? Student loan debt, debt stress, and racially/ethnically diverse college students’ perceived health . Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol . 2018;24(4):459-469. doi:10.1037/cdp0000207

American Psychological Association. Speaking of psychology: The stress of money .

Kraft AD, Quimbo SA, Solon O, Shimkhada R, Florentino J, Peabody JW. The health and cost impact of care delay and the experimental impact of insurance on reducing delays . J Pediatr . 2009;155(2):281-285.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.02.035

Richardson T, Elliott P, Roberts R. The relationship between personal unsecured debt and mental and physical health: A systematic review and meta-analysis . Clinical Psychology Review. 2013;33(8):1148-1162. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2013.08.009

Warth J, Puth M-T, Tillmann J, et al. Over-indebtedness and its association with sleep and sleep medication use . BMC Public Health . 2019;19(1):957. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-7231-1

Stress in America: Paying With Our Health . American Psychological Association..

Briguglio M, Vitale JA, Galentino R, et al. Healthy eating, physical activity, and sleep hygiene (HEPAS) as the winning triad for sustaining physical and mental health in patients at risk for or with neuropsychiatric disorders: Considerations for clinical practice . Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat . 2020;16:55-70. doi:10.2147/NDT.S229206

Zaccaro A, Piarulli A, Laurino M, et al. How breath-control can change your life: A systematic review on psycho-physiological correlates of slow breathing . Front Hum Neurosci . 2018;12:353. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2018.00353

Harvard Business Review. Research: The best strategy for paying off credit card debt .

American Psychological Association. Dealing with financial stress .

Han A, Kim J, Kim J. A study of leisure walking intensity levels on mental health and health perception of older adults . Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine. 2021. doi:10.1177/2333721421999316

American Psychological Association. Stress in America: Paying with our health .

Richardson T, Elliott P, Roberts R. The relationship between personal unsecured debt and mental and physical health: a systematic review and meta-analysis . Clin Psychol Rev . 2013;33(8):1148-1162. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2013.08.009

Saad L. Delaying care a healthcare strategy for three in 10 Americans .

By Elizabeth Scott, PhD Elizabeth Scott, PhD is an author, workshop leader, educator, and award-winning blogger on stress management, positive psychology, relationships, and emotional wellbeing.

Popular Searches

- Back to school

- Why do I feel weird

- School programs

- Managing stress

- When you’re worried about a friend who doesn’t want help

How To Deal With Financial Stress

Things that cause financial stress, effects of financial stress, get more financial tips, you're not alone.

Share this resource

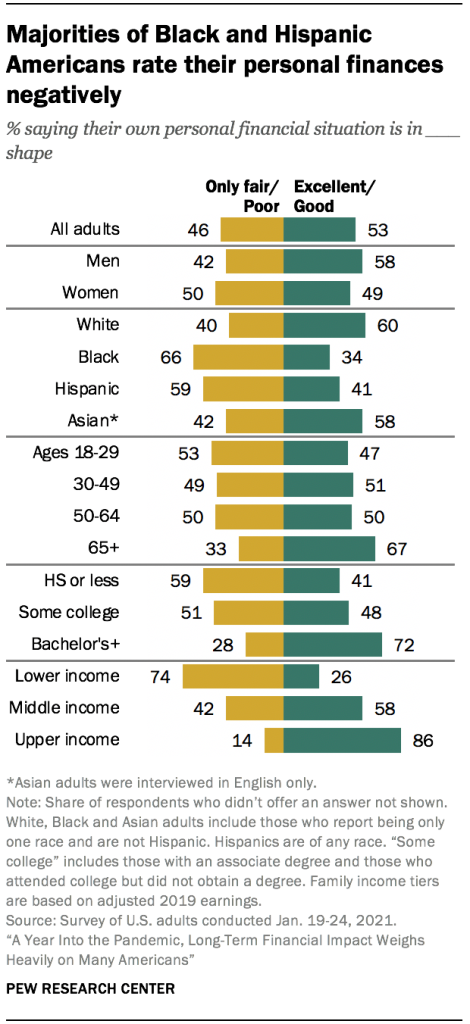

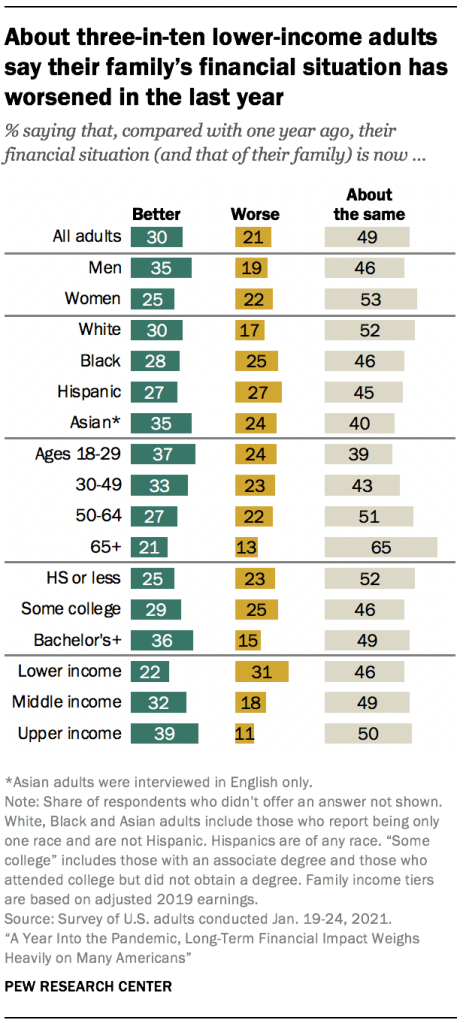

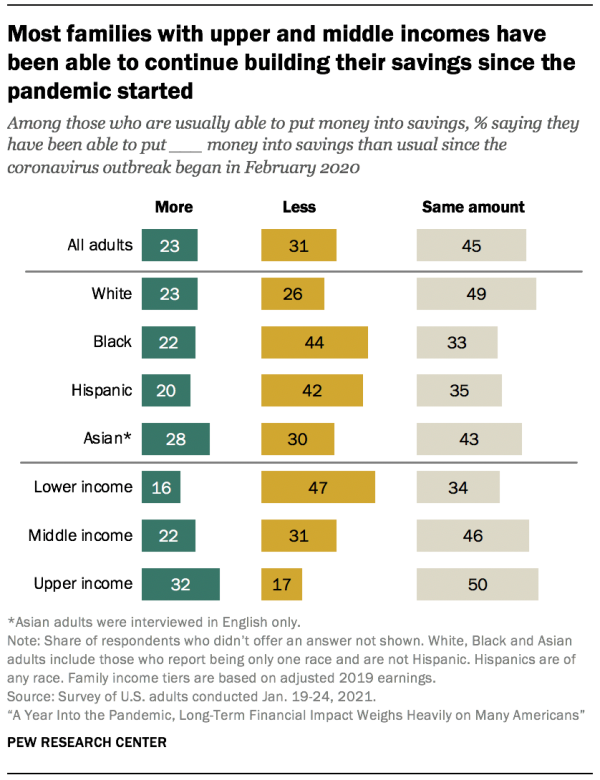

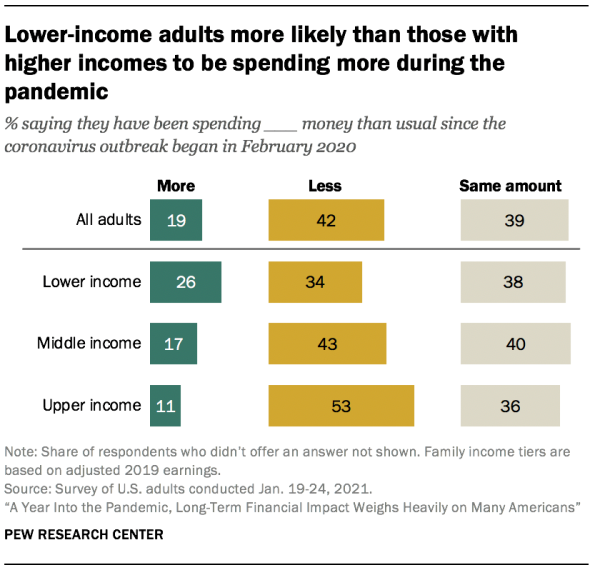

Financial stress is extremely common. According to an American Psychological Association (APA) study, even before the pandemic, over 70% of Americans reported concern about money. And, while a majority of Americans express concerns about their financial health, BIPOC Americans face disproportionately more financial challenges than their white counterparts. Because financial health is so deeply tied to our ability to meet core survival needs, worrying about money can have a significant impact on our mental and emotional wellbeing. Read on for more about the causes of financial stress and how you can take action to minimize and hopefully eliminate it.

There are many causes of financial stress. Sometimes it’s likely to be short term — such as when we lose a job or have unexpected but fleeting expenses. In these cases, a new job and some attentive budgeting can relieve the concern. Sometimes the stress is more chronic and rooted in deep structural inequities — such as the growing number of individuals and families who struggle to make ends meet even while working.

No matter what causes it, the stress of not knowing whether we can meet financial obligations, for ourselves and sometimes for others, can really take a toll on our mental health. And while money troubles or financial stress affects everyone, it may be especially challenging for young people who have less experience than older populations with managing finances. Although, it should be noted that often older people don’t have the physical, mental, or experiential capacity to work, while healthy young people typically have years of possible training and new skills acquisition ahead of them to help turn the tide.

Financial stress and mental health challenges can be mutually reinforcing. Like all stress, if left unaddressed, it can snowball into something bigger. Financial stress can damage mental health, and in turn, negative mental health can make it more challenging to manage our finances. When we’re under a lot of financial stress, we may experience emotional or physical symptoms like:

- Damage to self-esteem, shame, anger, fear, or despair

- Trouble sleeping, low energy or change in weight

- Trouble maintaining relationships or keeping an active social life

- Substance misuse

- Suicidal thoughts and behaviors

Suicide is an extreme response to financial stress and is always the result of a multifaceted array of factors, but financial stress is sometimes a contributor. More common effects of financial stress are depression and anxiety — especially in cases where there’s no clear solution to financial challenges. The most important thing is to identify the source of the stress and to move into problem solving mode whenever possible. Wanting to avoid the stress by avoiding the issue is understandable, but rarely works to actually alleviate the issue. And, in the case of financial stress, avoidance can make the situation much worse. Instead, it’s much more helpful to move into active problem solving mode and use whatever resources you have available. Here are some tips on how to get started:

Stay Connected to Friends and Family

When we’re struggling financially it’s tempting to want to pull away and minimize the challenge. Not having money to spend on socializing and/or feeling shame or embarrassment about our situation can make even admitting that we need help challenging. Our best resource, however, is other people. Sometimes, just having others around to provide emotional support can help us feel less alone. In other situations, friends and family might be able to help provide tactical and practical real-world advice or help you problem-solve, especially if they’ve been in a similar situation before. Remember that financial stress is common, so it’s highly likely that someone in your circle has experienced a similar situation before and will have ideas or at least short term assistance to offer.

Get Professional Financial Advice or Support

When you’re faced with chronic or structural challenges, it’s useful to know that there are organizations that provide free financial advice and other services. One that we know is the Foundation for Financial Planning . You can reach out to your personal bank for help as well. Many banks offer free counseling and financial advice; they’re a good resource because it’s in their best interest to help you. Of course, books are another great resource, and most libraries have a ton of information on financial planning. You can also Google “best books for financial advice” and see what comes up. And, as always, if you really need assistance immediately, there are government programs and benefits available. See if you qualify .

Track and Manage Your Finances

One of the best tools for reducing spending, and knowing where you spend money is by tracking and budgeting where you money goes. It’s always surprising where we spend money and most people don’t realize how much they spend on certain things. Here are a few ways to track and manage your finances:

- Download a financial tracking app, open up a spreadsheet, or just keep track on your phone. Whatever makes sense for you.

- Set a spending budget and stick with it. You can do this by setting a daily, weekly, or monthly budget. Some people like to break a budget down into categories while others might prefer having an overall monthly budget to stay within. Play around and see what works best for you. Be ambitious in cutting your spending, but also be realistic. Remember, change won’t happen overnight but if you stick with it, you will see improvements over time.

- If you need to save or make monthly payments, you can often arrange to have funds automatically debited from your account and moved into a savings account or applied to a bill as soon as you’re paid. Not including these automatic and immediate debits in your monthly budgeting for other expenses can make it much easier to save and pay bills.

- Set up a system or structure that makes it easy for you to stick to your budget, and keep in mind that there’s no one-size-fits-all. For some, it may be easier to track spending and stick to a budget by using a debit card and checking online statements regularly. For others, it may be easier to limit yourself to just using cash.

- Identify triggers for impulse purchases. You’d be surprised how easy it is to pick up small things you don’t need, so ensuring you’ve budgeted for it, and tracked it will really help curtail that unnecessary spending.

- Recognize the impact of small changes. Deciding to set a new spending budget can be intimidating, especially when you only think about it in terms of making big changes. But small changes, like removing a single online subscription, can really add up over time.

Managing The Stress of the Financial Crises

How to Deal With Money Anxiety by Building Financial Wellness

11 Money Terms to Learn Today

Related resources

How to find a good college fit as a latiné student, search resource center.

If you or someone you know needs to talk to someone right now, text, call, or chat 988 for a free confidential conversation with a trained counselor 24/7.

You can also contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741-741.

If this is a medical emergency or if there is immediate danger of harm, call 911 and explain that you need support for a mental health crisis.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- SAGE Open Med

A qualitative examination of the impacts of financial stress on college students’ well-being: Insights from a large, private institution

This qualitative research aims to provide deeper insight into college students’ experiences by examining the impact of financial stress on their well-being.

Four focus groups were conducted at a large, private, urban university in the United States over the course of 1 month, each lasting approximately 1 h. Facilitators used a structured moderator guide to maintain consistency. Four focus groups were conducted and a total of 30 students participated. Students were primarily Asian (66.7%) and White (30.0%), and a majority were female (86.7%). Student participants were 43.3% undergraduate and 56.6% graduate. Transcripts were analyzed in Atlas.ti 8 software using line-by-line open coding guided by the principles of qualitative content analysis. An inductive approach was utilized to code the data. Emergent categories and concepts were then organized hierarchically into themes and subthemes.

Two overarching themes emerged from the focus group analysis. In these students’ perspectives, financial stress impedes their ability to succeed academically. Another major theme is the impact of finances on students’ social lives. Students experiencing financial stress find it challenging to navigate relationships with wealthier peers, often leading to feelings of isolation and embarrassment.

Conclusion:

Given the reported negative impact on students’ well-being, further research is needed to determine methods for mitigating financial stress.

Introduction

The cost of attending college in the United States has increased by 31% over the last decade, demonstrating a substantial shift in the financial commitment associated with pursuing higher education. 1 Research suggests this rising cost may be cause for concern. According to the 2018 Healthy Minds Survey, US college students report their current financial situation as “stressful” (35%), “often stressful” (24%), “rarely stressful” (20%), “always stressful” (14%), and “never stressful” (7%). 2 Similarly, data from the National College Health Assessment 3 demonstrates that 75% of US students experienced moderate to high financial distress in the past 12 months.

There are many potential sources of financial stress for college students. A large number of students report being concerned about the amount of student loans they have taken out and their ability to repay these post graduation. 4 In addition to loans related to the cost of tuition and class supplies, many students also require cost-of-living loans because of their inability to work full time while pursuing an education. 5 Furthermore, many students are financially independent for the first time, resulting in an especially stressful time for them. 6 In fact, many university students struggle to meet basic needs while in school. Data collected by the Hope Center 7 on students at over 100 American colleges show that almost half of the students (45%) experienced food insecurity in the past 30 days and 17% experienced homelessness in the past year.

Research has demonstrated a link between financial stress and poorer mental health outcomes; for example, worry over finances has been correlated with mental illnesses like depression and anxiety. 8 , 9 Similar studies have also reported an association between financial stress and general poor mental health. 10 – 12 A literature review published by McCloud and Bann 13 purported students’ perceived financial stress is correlated with negative mental health outcomes. However, the link between financial stress and debt was not substantiated, suggesting perceived stress may be a more influential factor in mental health than the amount of debt accrued. 12 , 14 As McCloud and Bann 13 report, much of the existing literature utilizes cross-sectional study design, making it difficult to determine longitudinal impact of financial stress on mental health outcomes and demonstrating the need for more research to determine the relationship between these two factors.

In addition to challenges in students’ mental health, there is a link between financial stress and academic success, especially when it comes to student attrition. Studies have shown that students who experience higher levels of financial stress are more likely to discontinue their schooling than more financially secure peers. 15 , 16 In addition, data from the National College Health Assessment indicate that almost a quarter of students (24%) reported that finances negatively impacted performance in a class. 3 This may be due to having to work more hours to pay bills or for living expenses, which subsequently reduces the number of hours that can be committed to studying. 17 This could also be attributable to higher levels of stress or anxiety having a direct effect on academic performance, among other factors. 18

Given the importance of academics and well-being for college students, and the high prevalence of student financial stress, the goal of this study is to better understand the factors driving relationships between these constructs. Recent explorations of college student financial stress have provided valuable insights on this topic, including the impacts of financial stress on academic performance and social functioning. 11 , 16 , 19 However, a majority of this emerging research uses quantitative methodology, which cannot provide the nuance of qualitative research. There have been qualitative studies on university student stressors in general, 20 or on the impact of financial stress on more specific outcomes, but to our knowledge, there have not been qualitative data published on the richness of student experiences of financial stress and its relationship to well-being. Therefore, the aim of this research was to better understand the mechanisms, using a qualitative methodology, for the impact of financial stress on college student academic success and well-being. The hope is that this research can be used to uncover findings that university administrators can utilize to better support students. Although there is some variation in the terminology referring to the subjective experience of feeling distressed, worried, or concerned about one’s financial situation, 11 – 13 we refer to this broadly as “financial stress.”

Participants

A qualitative approach was utilized to gain a deeper understanding into the lived experiences of students with financial stress. Four focus groups were conducted at a large, private, urban university in the United States in September 2019. The student body, comprising 50,000 students, was approximately half undergraduate and half graduate students. About one quarter were international students, primarily from countries in Asia. Public data on family income was not available; however, the university reported that 22% of incoming first-year students were the first in their family to attend college and 18% of undergraduate students were recipients of Pell Grant US federal aid provided to low-income students. 21 Purposive sampling was used to recruit student participants who met the following criteria. First, participants had to be currently enrolled in an on-campus academic program at the university. Second, participants had to qualify by completing an online screener, which demonstrated an experience of current financial stress. This was measured using the question, “How would you describe your financial situation right now?” This one-item measure was chosen to align with national surveys investigating college student well-being. 2 , 22 Participants answered on a 5-point Likert-type scale from “never stressful” to “always stressful.” Those who selected “sometimes stressful,” “often stressful,” and “always stressful” (115 students) were invited to participate in one of the focus group sessions. Those who selected “never stressful” or “rarely stressful” (21 students) were not invited to participate.

Participants were recruited through distribution of a digital flyer in campus newsletters and student-facing social media accounts. Participants were also recruited from an email database of students who had previously indicated interest in focus group participation. Participants were offered a US$15 gift card upon completion of the focus group. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at this university. Participants were given information about the study and written informed consent was obtained via an online form prior to the focus groups.

Focus groups

Focus groups were facilitated by student Community Health Organizers. The role of the Community Health Organizers is to gather student input via peer focus groups and work closely with cross-departmental committees to shape programming, services, and policies centered on well-being. As student researchers, those who hold the Community Health Organizers roles are particularly invested in well-being and each brings their individual biases as a researcher. The Community Health Organizers completed a 2-day intensive training, which included instruction on qualitative data collection and analysis. Students learned how to organize and conduct focus groups, including recruitment strategies, techniques for facilitating diverse perspectives, and methods for recognizing personal bias in coding and analysis. The fall 2019 cohort of Community Health Organizers comprised seven students, both undergraduate and graduate, and included both male and female students.

The focus groups took place in various buildings on campus over the course of 1 month, each lasting approximately 1 h. At each focus group, two Community Health Organizers were present. One Community Health Organizer served as the primary facilitator and one served as note-taker. There was no one else present during the focus groups besides the participants and Community Health Organizers. Focus group participants did not have any prior relationship with the Community Health Organizers. To maintain consistency, students used a structured moderator guide to facilitate the focus groups ( Table 1 ). The moderator guide was tested internally with the research team prior to the focus groups. Participant demographics were also collected. The recommended sample size for focus group discussions is 5–8 people per group and a minimum of four groups to achieve code saturation. 23 The research team held four focus groups to meet this recommendation.

Focus group moderator guide key questions.

All focus groups were audio recorded and files were transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were not returned to participants for comment or correction. Transcripts were analyzed in Atlas.ti 8 software using line-by-line open coding guided by the principles of qualitative content analysis. An inductive approach was utilized to code the data. Each transcript was independently coded by two raters. After each round of independent coding, raters compared codes to discuss discrepancies and reach consensus. Emergent categories and concepts were then organized hierarchically into themes and subthemes. 24 The final coding scheme and all transcripts were reviewed by the investigative team to ensure that they accurately captured the topics that were discussed in the focus groups. Participants did not provide feedback on the findings.

A total of 30 students participated in four focus groups (5–9 students per group). A total of 21 additional students met the eligibility criteria and signed up to attend a focus group, but did not show up on the day of the focus groups. Reasons for dropping out are unknown. Of the 30 participants, students were primarily Asian (66.7%) and White (30.0%), and a majority were female (86.7%; Table 2 ). Student participants were 43.3% undergraduate and 56.6% graduate. Participants were about evenly split into domestic (56.7%) and international (43.3%) students. Similarly, about half (46.7%) were first-generation students and 40.0% of students were receiving financial aid. Participants’ annual family income varied, with 16.7% of participants reporting less than US$25,000 and 13.3% of participants reporting greater than US$100,000 annual family income. To protect participants’ anonymity, information on academic program, age, disability status, grade point average (GPA), and employment status was not gathered.

Demographic characteristics of student focus group participants.

Two overarching themes emerged from the focus group analysis. First, students felt the effects of financial stress play out significantly in their academic lives. In these students’ perspectives, their financial status impedes their ability to succeed academically. Another major theme is the impact of finances on students’ social lives. As subsequent data show, students experiencing financial stress find it challenging to navigate relationships with wealthier peers, often leading to feelings of isolation and embarrassment.

Academic consequences

Inability to purchase textbooks.

To explore academic challenges associated with financial stress, facilitators asked participants, “When it’s hard to pay for things you need or want, how does that affect you academically?” The high cost of textbooks and other online materials was named frequently as a stressor for students. Course materials contributed to “constant worry” about finances, particularly at the beginning of each semester. One student reported avoiding certain classes because they could not afford the required materials. Others feared if they were unable to pay for course materials, their grades would suffer. It was difficult for many students to decide whether to purchase expensive textbooks or pay for other necessary expenses like rent or even “very basic amenities.” When faced with this challenging decision, most students opted to pay for necessities. Without access to course materials, students developed resourceful methods for staying afloat. To avoid purchasing expensive textbooks, one student asked classmates to borrow books so they could take photos of the pages. Another student mentioned purchasing outdated versions of textbooks. While some of the content was similar, there were instances where the old editions did not suffice. The student gave an example where they could not complete practice problems the professor assigned, causing them to fall behind in class.

Prioritizing work over studies

Another common theme among students was the difficult decision to prioritize on- or off-campus jobs over their academics. Students often mentioned how their studies suffered because they had to continue working to earn money. One participant described the challenge of balancing work and academics during exams. The student wanted to take time off to focus on their studies, but had to work instead to maintain basic living expenses. Another expressed a similar sentiment, adding they felt jealous of other students who did not have to work, saying:

. . . you get things wrong or maybe you didn’t so well on this test, but you’re like, “Oh, I had to work a lot last week.” And then you feel bad, some of these other kids in my class who clearly have a lot of money, you know that they didn’t have to work and they could just spend time studying, and that’s also something that I think has hurt me and has hurt my grades. [Undergraduate]

Stress as a distraction from academics

Many discussed how constant stress over finances distracted from their academics. Students mentioned the inability to focus on their studies when their thoughts are constantly preoccupied with expenses. One student explained,

. . . in the back of my mind it’s like, “Oh this payment is coming,” or like, “I have to pay this,” or like, “This is the amount I have in my bank account, oh my god.” These thoughts are constantly in my head, and they prevent me from fully focusing at what’s in front of me and doing as well as, the best I can in my classes. [Undergraduate]

Students perceived this stressor as unique to those experiencing financial stress. They often characterized their constant worry as “unfair” when comparing their situation to students of more means.

Unable to further career goals

In all focus groups, students cited their jobs as an impediment to furthering their career goals. Students felt their jobs were necessary to earn money, but prevented them from pursuing other opportunities. Many identified their jobs as “just something to pay the bills” and “not a value add for my career.” Students expressed desire to take on extracurricular projects or jobs that would advance career goals, as opposed to working solely to earn money.

Many students reported they could not afford to participate in career-enhancing extracurriculars. These extracurriculars were characterized as having “amazing opportunities” for gaining valuable experience outside the classroom. However, many extracurriculars at the university include membership fees or event expenses for which these students could not pay. For example, one student mentioned their disappointment in missing a service trip, which included travel and mentorship by university staff. Two students perceived financial stress as a barrier to networking opportunities, with one expressing dismay at the expensive dues of a professional fraternity. Another described the university as “all about connections.” Wealthy students were seen as already having connections, thus more easily transitioning to a fulfilling job after graduation. Students who were “on the poorer end” had to work even harder to establish professional contacts.

Social consequences

In addition to academic strains, students felt the effects of financial stress strongly in their social lives, which further impacted their sense of belonging and well-being.

Social comparison

Students frequently compared financial status with those of their peers, finding they had to work harder than other students to achieve the same goals. Many made statements like “they’re able to do things easily” and “everybody else has an easier time,” perceiving other students to be at an advantage due to their socioeconomic status. A few students explicitly mentioned the school’s reputation as a school for the wealthy and privileged, describing the university as “for really rich people and legacies” and “where all the wealthy people are.” Constant social comparison to wealthier peers caused these students to feel ostracized and not fully part of the university community.

Class separation and its consequences

As a result of perpetual social comparison, students felt a clear class separation between the “haves” and the “have nots.” In all four focus groups, participants mentioned a clear social divide at the school based on financial status. One student said,

I feel like all the really, really rich kids tend to just migrate towards each other, and there is this circle, or this little bubble of wealth, and it’s kind of impossible to penetrate into it, unless you can afford to do spring break in Cabo. [Undergraduate]

Due to the clear distinction in financial status, many students felt excluded from certain social experiences. Students mentioned their inability to participate in informal social gatherings, like going on trips with friends. These students were typically invited to participate by their friends, but had to decline because they could not afford to go. Some students were upfront with their friends, citing their inability to pay. However, many felt uncomfortable discussing their lack of finances and fabricated other excuses.

In addition to informal gatherings, others cited exclusion from “official” university social experiences, such as student organizations, Greek life, and football games. Students wanted to participate, but could not justify the associated costs. One student poignantly described the feeling of missing out on these experiences:

. . . the social factor is such a big part of what makes the [school] experience, so I feel like I really missed out on a big portion of that, so if I graduate, and I were to talk to another [school] graduate, I feel like we wouldn't be able to connect on a really big portion of what's supposed to be a mutual experience. [Undergraduate]

Feeling self-conscious/embarrassed/ashamed

Many students expressed feelings of embarrassment or shame as a result of their financial status. One said, “for the lack of a better word, I would say it feels just bad . . . you feel kind of like a loner at times.” Some were afraid of being perceived as “cheap” for their unwillingness to spend money for social outings. Others described specific instances where they felt targeted for their financial status. One student suspected they were rejected from a professional organization because they had to “cobble together some stuff . . . at Goodwill” for the final round interview. The student said they were not explicitly denied based on their financial status, but it left them with a sinking feeling that their suit from Goodwill had played a part. Another reported an instance where they were confronted by a friend who demanded to know why the student was always trying to “take benefits from other people.” One student cited an experience where she was the target of gossip in her residence hall because she had complained about the cost of doing laundry.

Navigating the divide

To remain friends with wealthier students, students with financial stress adopted a variety of methods for participating in social outings. Some took on the responsibility of orchestrating plans so they could afford to participate. For example, one student described how they are “strategic about it,” suggesting low-cost restaurants and asking friends to go on a hike instead of paying for an expensive event ticket. However, in most cases, students with financial stress end up skipping these social outings altogether. Unable to participate, students reported feelings of disappointment and alienation. One student dejectedly characterized themselves as the friend that “ruins everything.”

Bonding with other low-income students

While some friendships with peers were described as hard to maintain, many students formed close relationships with others experiencing financial stress. One student found that these relationships were easier because “it feels like you’re not alone in this.” Other students echoed this sentiment, adding that these friendships provide “a nice community where I feel I fit in.” Together, these students found free events on campus to attend. They also described swapping stories about their financial stress, using humor to cope with tough financial situations. Two students said they developed friendships through the first-generation student union, an on-campus space for scholarship recipients. This student union was described as “a more welcoming space” than other venues on campus and an easy way for students to find like-minded peers.

Data from these focus groups illustrate that students experience the effects of financial stress in their academic studies and in their social lives. Financial stress may be a barrier to achieving academic success, as it prevented students from purchasing textbooks, caused them to prioritize jobs over coursework, and stood in the way of furthering career goals. Financial stress was also tied to students’ social lives. Students often made social comparisons to peers, perceiving others as having more disposable income. This constant comparison resulted in feelings of shame and frustration. These students also described how those with financial stress encounter a vastly different college experience, as they struggled to maintain friendships with wealthier peers and felt unable to participate in social events. Interestingly, 13% of participants identified their annual family income as greater than US$100,000. This may suggest financial stress is not necessarily exclusive to low-income students, and middle-class students may also be experiencing similar challenges. Alternately, financial stress may be driven by students’ comparison to wealthy peers, rather than their financial status. Future research could seek to better understand the prevalence of these academic and social consequences.

The insights gathered from these focus groups support previous findings on the impact of financial stress on college students. Joo et al. 16 found financially stressed students reported poorer academic performance than their peers. Bennett et al. 17 echoed these findings, demonstrating students with financial stress spend more time at work, resulting in significantly lower course grades. Student perspectives from these qualitative findings produced similar themes, detailing how work responsibilities can be a barrier for academic achievement. These findings also point to possible long-term effects of financial stress years after college, with students describing their inability to strengthen their career capital in comparison to their peers. Longitudinal research has shown financial stress can cause students to drop out of college; 25 however, for those who persist, future research could explore whether financial stress is a determining factor in students’ post-graduation career prospects.

Data from our study also support findings that the inability to participate in activities with peers is one of the most salient financial stressors for students. 26 As demonstrated by students’ firsthand experiences, their inability to participate in either on-campus events or more informal social gatherings led to feelings of embarrassment, shame, and frustration. These adverse effects on peer-to-peer relationships are striking, as social support is one of the strongest predictors of one’s well-being. 27 As demonstrated in previous research, students experiencing financial stress report poorer subjective well-being. 6 Future research could more deeply explore whether financial stress impacts the relationship between social support and overall well-being.

As evidenced by students’ rich perspectives, it may be difficult for students to receive the full benefits of a college education when their social and academic lives are impeded by financial stress. To address these negative outcomes, university administrators who develop policy and allocate resources will need to consider both the downstream effects of financial stress as well as its root causes. Further research is needed to determine the most effective interventions for mitigating financial stress in a university setting. However, the preliminary evidence from this qualitative research suggests there are a few key areas for administrators to consider. First, academic programs can allocate budget dollars to cover the cost of textbooks or require professors to offer low- or no-cost options. This could ensure all students, regardless of financial status, have adequate access to course materials. Universities can also review available student jobs and incentivize departments to develop job opportunities more in line with students’ career goals. This could satisfy both students’ need to earn money and their desire to gain a valuable experience related to their career aspirations. Colleges may want to consider a policy in which all student worker jobs offer a set amount of paid time off to use in conjunction with major exams, reducing the burden on students who feel they must prioritize work over academics.