Shooting an Elephant

George orwell, everything you need for every book you read..

Orwell uses his experience of shooting an elephant as a metaphor for his experience with the institution of colonialism. He writes that the encounter with the elephant gave him insight into “the real motives for which despotic governments act.” Killing the elephant as it peacefully eats grass is indisputably an act of barbarism—one that symbolizes the barbarity of colonialism as a whole. The elephant’s rebelliousness does not justify Orwell’s choice to kill it. Rather, its rampage is a result of a life spent in captivity—Orwell explains that “tame elephants always are [chained up] when their attack of “must” is due.” Similarly, the sometimes-violent disrespect that British like Orwell receive from locals is a justified consequence of the restraints the colonial regime imposes on its subjects. Moreover, just as Orwell knows he should not harm the elephant, he knows that the locals do not deserve to be oppressed and subjugated. Nevertheless, he ends up killing the elephant and dreams of harming insolent Burmese, simply because he fears being laughed at by the Burmese if he acts any other way. By showing how the conventions of colonialism force him to behave barbarically for no reason beyond the conventions themselves, Orwell illustrates that “when the white man turns tyrant it is his own freedom that he destroys.”

Colonialism ThemeTracker

Colonialism Quotes in Shooting an Elephant

With one part of my mind I thought of the British Raj as an unbreakable tyranny, as something clamped down, in saecula saeculorum, upon the will of prostrate peoples; with another part I thought that the greatest joy in the world would be to drive a bayonet into a Buddhist priest's guts. Feelings like these are the normal by-products of imperialism; ask any Anglo-Indian official, if you can catch him off duty.

That is invariably the case in the East; a story always sounds clear enough at a distance, but the nearer you get to the scene of events the vaguer it becomes.

And it was at this moment, as I stood there with the rifle in my hands, that I first grasped the hollowness, the futility of the white man's dominion in the East. Here was I, the white man with his gun, standing in front of the unarmed native crowd – seemingly the leading actor of the piece; but in reality I was only an absurd puppet pushed to and fro by the will of those yellow faces behind. I perceived in this moment that when the white man turns tyrant it is his own freedom that he destroys. He becomes a sort of hollow, posing dummy, the conventionalized figure of a sahib. For it is the condition of his rule that he shall spend his life in trying to impress the "natives," and so in every crisis he has got to do what the "natives" expect of him. He wears a mask, and his face grows to fit it. I had got to shoot the elephant.

A white man mustn't be frightened in front of "natives"; and so, in general, he isn't frightened. The sole thought in my mind was that if anything went wrong those two thousand Burmans would see me pursued, caught, trampled on and reduced to a grinning corpse like that Indian up the hill. And if that happened it was quite probable that some of them would laugh. That would never do.

And afterwards I was very glad that the coolie had been killed; it put me legally in the right and it gave me a sufficient pretext for shooting the elephant. I often wondered whether any of the others grasped that I had done it solely to avoid looking a fool.

Literary Journalism and Social Justice pp 117–128 Cite as

Making Visible the Invisible: George Orwell’s “Marrakech”

- Russell Frank 3

- First Online: 05 August 2022

202 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Much of the best literary journalism shows us what we do not and perhaps wish not to see. Nowhere is the mission of making visible those who are invisible articulated as explicitly as in George Orwell’s 1939 essay “Marrakech.” The colonial enterprise, Orwell tells us, is predicated on not seeing as fully human those whom we subjugate. If we did, we would have to reckon not only with their misery but with our complicity in their subjugation and misery. This chapter argues for the critical role of “Marrakech,” and literary journalism in general, in the shift from the ethnocentrism that underpins colonization abroad and domestic oppression at home, to recognition of our common humanity.

- Literary journalism

- George Orwell

- Colonialism

- Ethnocentrism

- Journalism history

- Narrative journalism

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Kevin Kerrane and Ben Yagoda, eds., The Art of Fact: A Historical Anthology of Literary Journalism (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1998).

George Orwell, “Marrakech,” in The Art of Fact , eds. Kevin Kerrane and Ben Yagoda (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1998), 434.

Orwell, “Marrakech,” 435.

Orwell, “Marrakech,” 437.

Karim Bejjit Hassan II, “Orwell’s Marrakech: Desolate Spaces, Dehumanised Subjects,” Writing the Maghreb , https://writingthemaghreb.wordpress.com/2011/07/11/orwell’s-marrakech-desolate-spaces-dehumanised-subjects/ .

Hassan, “Orwell’s Marrakech.”

Thomas March, “Orwell’s Marrakech,” Explicator 57, Spring 1999, 163–164.

Orwell, “Marrakech,” 434.

Sylvester Monroe and Peter Goldman, “Brothers,” in The Art of Fact , 204–211.

Monroe and Goldman, “Brothers,” 208.

Orwell, “Marrakech,” 436.

James Agee, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men: Three Tenant Families (Boston: Houghton-Mifflin, 1969), 38–43.

Orwell, “Marrakech,” 438.

Cleo McNelly, “On Not Teaching Orwell,” College English 38, no. 6 (1977): 553. https://doi.org/10.2307/376095 .

Ryszard Kapuscinski, “Another Day of Life,” in The Art of Fact , 507–521.

Kapuscinski, “Another Day of Life,” 515.

Kapuscinski, “Another Day of Life,” 508.

Orwell, “The Spike,” in The Art of Fact , 245–251.

Stephen Crane, “An Experiment in Misery,” in The Art of Fact , 63–70.

Jack London, from The People of the Abyss, in The Art of Fact , 83–89.

Marvel Cooke, from “The Bronx Slave Market,” in The Art of Fact , 252–257.

Ted Conover, from Coyotes, in The Art of Fact , 331–335.

Charles Dickens, “The Great Tasmania’ s Cargo,” in The Art of Fact , 38–45.

Walt Whitman from Specimen Days , in The Art of Fact , 46–48.

Martha Gellhorn, “The Third Winter,” in The Art of Fact , 422–432.

John Steinbeck, from Once There Was a War, in The Art of Fact , 458–460.

Walter Bernstein, “Juke Joint,” in The Art of Fact , 104–110.

John Hersey, from Hiroshima , in The Art of Fact , 111–114.

Michael Herr, from Dispatches, in The Art of Fact , 494–506.

Svetlana Alexievich, from Boys in Zinc, in The Art of Fact , 536–548.

Lillian Ross, from “Portrait of Hemingway,” in The Art of Fact , 129–138 .

W.C. Heinz, “The Day of the Fight,” in The Art of Fact , 115–128.

Gay Talese, “The Silent Season of a Hero,” in The Art of Fact , 143–160.

Al Stump, “The Fight to Live,” in The Art of Fact , 271–289 .

Bob Greene, “So … We Meet at Last, Mr. Bond,” in The Art of Fact , 212–217.

Richard Ben Cramer, from What It Takes: The Way to the White House , in The Art of Fact , 236–241.

W.T. Stead, from If Christ Came to Chicago , in The Art of Fact , 49–57 .

Abraham Cahan, “Can’t Get Their Minds Ashore” and “Pillelu, Pillelu!” in The Art of Fact , 76–82.

Joseph Mitchell, “Lady Olga,” in The Art of Fact , 439–451.

Rosemary Mahoney, from Whoredom in Kimmage , in The Art of Fact , 367–383.

Dennis Covington, from “Snake Handling and Redemption,” in The Art of Fact , 391–403.

Tom Wolfe, from The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test , in The Art of Fact , 169–182.

Gary Smith, “Shadow of a Nation,” in The Art of Fact , 218–235 .

Bill Buford, from Among the Thugs, in The Art of Fact , 354–366.

Daniel Defoe, from The True and Genuine Account of the Life and Actions of the Late Jonathan Wild , in The Art of Fact , 23–28 .

Hickman Powell, from Ninety Times Guilty, in The Art of Fact , 97–103.

Truman Capote, from In Cold Blood , in The Art of Fact , 161–168.

Katherine Boo, Behind the Beautiful Forevers (New York: Random House, 2014), 36–37.

Stephen Crane, “An Experiment in Misery,” 70.

Francois Rabelais, and Burton Raffel, Gargantua and Pantagruel (New York: Norton, 1990). The Rabelais quote is the source for the title of Jacob Riis’ How the Other Half Lives (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1890).

London, from The People of the Abyss , 84.

Tracy Kidder, Mountains Beyond Mountains (New York: Random House, 2003).

Orwell, “The Spike,” 247.

Orwell, “The Spike,” 249.

Cooke, from “The Bronx Slave Market,” 256.

Sylvester Graham, “Harlem on My Mind,” in The Art of Fact , 386.

See also Barbara Ehrenreich, Nickel and Dimed: On Not Getting by in America (New York: Henry Holt, 2002).

James Agee, from Let Us Now Praise Famous Men , in The Art of Fact , 417–421.

Rebecca West, from Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, in The Art of Fact , 456.

West, from Black Lamb and Grey Falcon , 457.

James Clifford, “On Ethnographic Surrealism,” in The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art (Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 1988), 121.

Clifford, “On Ethnographic Surrealism,” 120.

See, for example, Barbara Myerhoff and Jay Ruby, eds., A Crack in the Mirror: Reflexive Perspectives in Anthropology , introduction (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1982).

Viet Thanh Nguyen, ed., The Displaced: Refugee Writers on Refugee Lives , (New York, NY: Abrams, 2018), introduction, Kindle.

Nguyen, The Displaced , introduction.

Daniel Trilling, Lights in the Distance: Exile and Refuge at the Borders of Europe , (London: Picador, 2019), chap. 21, Kindle.

Wesley Lowery, They Can’t Kill Us All: Ferguson, Baltimore, and a New Era in America’s Racial Justice Movement (Little Brown & Company, 2017), 58.

Bibliography

Agee, James, and Walker Evans. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men . Boston: Houghton-Mifflin, 1939 and 1940.

Google Scholar

Boo, Katherine. Behind the Beautiful Forevers. New York: Random House, 2014.

Clifford, James. “On Ethnographic Surrealism.” In The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art, 117–151 . Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 1988.

Chapter Google Scholar

Hassan, Karim Bejjit II. “Orwell’s Marrakech: Desolate Spaces, Dehumanised Subjects.” Writing the Maghreb (July 2011) . https://writingthemaghreb.wordpress.com/2011/07/11/orwell’s-marrakech-desolate-spaces-dehumanised-subjects/ .

Kerrane, Kevin, and Ben Yagoda, eds. The Art of Fact: A Historical Anthology of Literary Journalism . New York: Simon & Schuster, 1998.

Kidder, Tracy. Mountains beyond Mountains . New York: Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2014.

Lowery, Wesley. They Can’t Kill Us All: Ferguson, Baltimore, and a New Era in America’s Racial Justice Movement . Little Brown & Company, 2017.

McNelly, Cleo. “On Not Teaching Orwell.” College English 38, no. 6 (1977): 553. https://doi.org/10.2307/376095 .

Article Google Scholar

Myerhoff, Barbara and Jay Ruby. “Introduction.” In A Crack in the Mirror: Reflexive Perspectives in Anthropology , edited by Myerhoff and Ruby, 1–35 . Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Nguyen, Viet Thanh. “Introduction.” In The Displaced: Refugee Writers on Refugee Lives . Edited by Nguyen. New York: Abrams, 2018. Kindle.

Rabelais, Francois and Burton Raffel. Gargantua and Pantagruel. New York: Norton, 1990.

Riis, Jacob A. How the Other Half Lives: Studies among the Tenements of New York. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1890.

Book Google Scholar

Trilling, Daniel. Lights in the Distance: Exile and Refuge at the Borders of Europe . London: Picador, 2019.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, USA

Russell Frank

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Russell Frank .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of English Language and Literature, Brock University, St. Catharines, ON, Canada

Robert Alexander

Faculty of Arts Department of Media, Communications, Creative Arts, Language and Literature (MCCALL), Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Willa McDonald

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Frank, R. (2022). Making Visible the Invisible: George Orwell’s “Marrakech”. In: Alexander, R., McDonald, W. (eds) Literary Journalism and Social Justice . Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-89420-7_8

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-89420-7_8

Published : 05 August 2022

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-89419-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-89420-7

eBook Packages : Literature, Cultural and Media Studies Literature, Cultural and Media Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Lesson Plans

- Teacher's Guides

- Media Resources

George Orwell's Essay on his Life in Burma: "Shooting An Elephant"

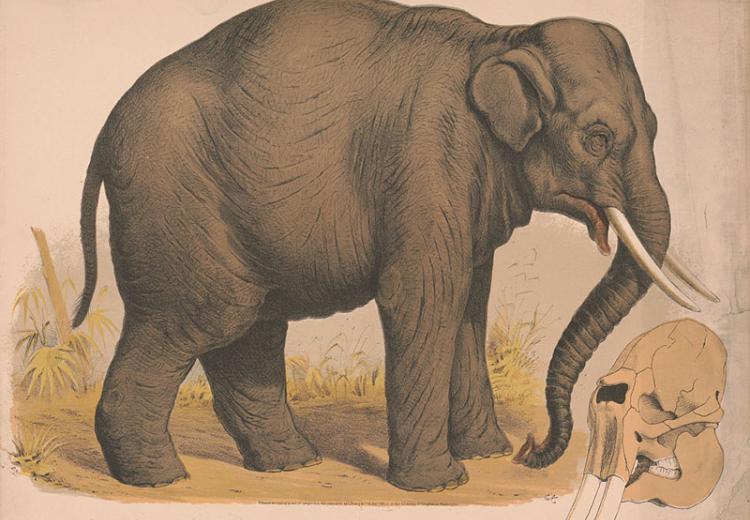

George Orwell confronted an Asian elephant like this one in the story recounted for this lesson plan.

Library of Congress

Eric A. Blair, better known by his pen name, George Orwell, is today best known for his last two novels, the anti-totalitarian works Animal Farm and 1984 . He was also an accomplished and experienced essayist, writing on topics as diverse as anti-Semitism in England, Rudyard Kipling, Salvador Dali, and nationalism. Among his most powerful essays is the 1931 autobiographical essay "Shooting an Elephant," which Orwell based on his experience as a police officer in colonial Burma.

This lesson plan is designed to help students read Orwell's essay both as a work of literature and as a window into the historical context about which it was written. This lesson plan may be used in both the History and Social Studies classroom and the Literature and Language Arts classroom.

Guiding Questions

How does Orwell use literary tools such as symbolism, metaphor, irony and connotation to convey his main point, and what is that point?

What is Orwell's argument or message, and what persuasive tools does he use to make it?

Learning Objectives

Analyze Orwell's essay within its appropriate cultural and historical context.

Evaluate the main points of this essay.

Discuss Orwell's use of persuasive tools such as symbolism, metaphor, and irony in this essay, and explain how he uses each of these tools to convey his argument or message.

Lesson Plan Details

The essay "Shooting an Elephant" is set in a town in southern Burma during the colonial period. The country that is today Burma (Myanmar) was, during the time of Orwell's experiences in the colony, a province of India, itself a British colony. Prior to British intervention in the nineteenth century Burma was a sovereign kingdom. After three wars between British forces and the Burmese, beginning with the First Anglo-Burmese War in 1824-26, followed by the Second Anglo-Burmese War of 1852, the country fell under British control after its defeat in the Third Anglo-Burmese War in 1885. Burma was subsumed under the administration of British India, becoming a province of that colony in 1886. It would remain an Indian province until it was granted the status of an individual British colony in 1937. Burma would gain its independence in January 1948.

Eric A. Blair was born in Mohitari, India, in 1903 to parents in the Indian Civil Service. His education brought him to England where he would study at Eton College ("college" in England is roughly equivalent to a US high school). However, he was unable to win a scholarship to continue his studies at the university level. With few opportunities available, he would follow his parents' path into service for the British Empire, joining the Indian Imperial Police in 1922. He would be stationed in what is today Burma (Myanmar) until 1927 when he would quit the imperial civil service in disgust. His experiences as a policeman for the Empire would form the basis of his early writing, including the novel Burmese Days as well as the essay "Shooting an Elephant." These experiences would continue to influence his world view and his writing until his death in 1950.

- Review George Orwell's Shooting an Elephant . The text is available through the EDSITEment-reviewed web resource Center for the Liberal Arts .

- Familiarize yourself with the historical context of Orwell's story, as well as the biographical circumstances that placed him in Burma as a police officer. Additional information on Burmese history , the British Empire in India and the biography of George Orwell can be accessed through the EDSITEment-reviewed web resource Internet Public Library.

- Review metaphor , imagery , irony , symbolism and connotative and denotative language. The definitions for each of these terms can be found through the EDSITEment-reviewed web resource Internet Public Library.

Activity 1. British Bobbies in Burma

It was once said that the sun never set on the British Empire, whose territory touched every continent on earth. English imperialism evolved through several phases, including the early colonization of North America, to its involvement in South Asia, the colonization of Australia and New Zealand, its role in the nineteenth century scramble for Africa, involvement with politics in the Middle East, and its expansion into Southeast Asia. At the height of its power in the early twentieth century the British Empire had control over nearly two-fifths of the world's land mass and governed an empire of between 300 and 400 million people. It is the addition of the Southeast Asian countries today known as Burma (Myanmar), Malaysia and Singapore that set the stage for Orwell's vignette from the life of a colonial official.

- Review with students the history of the British Empire. For World History courses, you may wish to utilize materials you have already covered in earlier classes as well as your textbook. You may also wish to use the overview of the British Empire that is available through the EDSITEment-reviewed web resource Internet Public Library.

- Ask students to look at this late nineteenth century map of the British Empire . Have students note which continents had a British colonial presence at the time this map was drawn in 1897. Next, ask students to read through the list of territories which were part of the British Empire in 1921 . Again, ask students to note which continents had a British colonial presence that year. Both the map and the list of territories are available through the EDSITEment-reviewed web resource Internet Public Library.

- Ask students to read the history of British involvement in Burma available through the EDSITEment-reviewed web resource Internet Public Library.

- Introduce students to Eric Blair, the man who would take the pen name George Orwell. You may wish to do so by reading the background information above to the class, or by reading a short biography of the writer available through the EDSITEment-reviewed Internet Public Library. Explain that Orwell would spend five years in Burma as an Indian Imperial Police officer. This experience allowed him to see the workings of the British Empire on a daily and very personal level.

Activity 2. The Reluctant Imperialist

Ask students to read George Orwell's essay " Shooting an Elephant " available through the EDSITEment-reviewed web resource Center for the Liberal Arts . Ask students to take notes as they read of their first impressions, questions that may arise, or their reactions to the story. Ask them to also note any metaphors, symbolism or examples of irony in the text.

- How does Orwell feel about the British presence in Burma? How does he feel about his job with the Indian Imperial police? What are some of the internal conflicts Orwell describes feeling in his role as a colonial police officer? How do you know?

- He wrote and published this essay a number of years after he had left the civil service. How does Orwell describe his feelings about the British Empire, and about his role in it, both at the time he took part in the incident described, and at the time of writing the essay, after having had the opportunity to reflect upon these experiences? Ask students to point to examples in the text which support their view.

- What did Orwell mean by the following sentence: It was a tiny incident in itself, but it gave me a better glimpse than I had had before of the real nature of imperialism -- the real motives for which despotic governments act .

"All this was perplexing and upsetting. For at that time I had already made up my mind that imperialism was an evil thing and the sooner I chucked up my job and got out of it the better. Theoretically—and secretly, of course—I was all for the Burmese and all against their oppressors, the British. As for the job I was doing, I hated it more bitterly than I can perhaps make clear. In a job like that you see the dirty work of Empire at close quarters. The wretched prisoners huddling in the stinking cages of the lock-ups, the grey, cowed faces of the long-term convicts, the scarred buttocks of the men who had been flogged with bamboos—all these oppressed me with an intolerable sense of guilt. But I could get nothing into perspective. I was young and ill-educated and I had had to think out my problems in the utter silence that is imposed on every Englishman in the East… All I knew was that I was stuck between my hatred of the empire I served and my rage against the evil-spirited little beasts who tried to make my job impossible. With one part of my mind I thought of the British Raj as an unbreakable tyranny, as something clamped down, in saecula saeculorum *, upon the will of the prostrate peoples; with another part I thought that the greatest joy in the world would be to drive a bayonet into a Buddhist priest's guts. Feelings like these are the normal by-products of imperialism; ask any Anglo-Indian official, if you can catch him off duty." * In saecula saeculorum is a liturgical term meaning "for ever and ever"

- Orwell states that he was against the British in their oppression of the Burmese. However, Orwell himself was British, and in his role as a police officer he was part of the oppression he is speaking against. How can he be against the British and their empire when he is a British officer of the empire?

- What does Orwell mean when he writes that he was "theoretically… all for the Burmese and all against their oppressors." Why does he use the word "theoretically" in this sentence, and what does he mean by it?

- How does this "theoretical" belief conflict with his actual feelings? Does he show empathy or sympathy for the Burmese in his description of this incident? Does he show a lack of sympathy? Both? Ask students to focus on the kind of language Orwell uses. How does he convey these feelings through his use of language?

- Does Orwell believe these conflicting feelings can be reconciled? Why or why not?

- What does he mean by "the utter silence that is imposed on every Englishman in the East"?

"I was sub-divisional police officer of the town, and in an aimless, petty kind of way anti-European feeling was very bitter. No one had the guts to raise a riot, but if a European woman went through the bazaars alone somebody would probably spit betel juice over her dress. As a police officer I was an obvious target and was baited whenever it seemed safe to do so. When a nimble Burman tripped me up on the football field and the referee (another Burman) looked the other way, the crowd yelled with hideous laughter. This happened more than once. In the end the sneering yellow faces of young men that met me everywhere, the insults hooted after me when I was at a safe distance, got badly on my nerves. The young Buddhist priests were the worst of all. There were several thousands of them in the town and none of them seemed to have anything to do except stand on street corners and jeer at Europeans ."

- Knowing that Orwell had sympathy for the position of the Burmese under colonialism, how does it make you feel to read the description of the way in which he was treated as a policeman?

- Why do you think the Burmese insulted and laughed at him?

- The first sentence of this paragraph is "In Moulmein, in lower Burma, I was hated by large numbers of people- the only time in my life that I have been important enough for this to happen to me." What does he mean when he says he was "important enough" to be hated?

- As a colonial police officer Orwell was both a visible and accessible symbol to many Burmese. What did he symbolize to the Burmese?

- Orwell was unhappy and angry in his position as a colonial police officer. Why? At whom was his anger directed? What did the Burmese symbolize to Orwell?

Activity 3. The Price of Saving Face

Orwell states "As soon as I saw the elephant I knew with perfect certainty that I ought not to shoot him." Later he says "… I did not want to shoot the elephant." Despite feeling that he ought not take this course of action, and feeling that he wished not to take this course, he also feels compelled to shoot the animal. In this activity students will be asked to discuss the reasons why Orwell felt he had to kill the elephant.

"It was perfectly clear to me what I ought to do. I ought to walk up to within, say, twenty-five yards of the elephant and test his behavior. If he charged, I could shoot; if he took no notice of me, it would be safe to leave him until the mahout came back. But also I knew that I was going to do no such thing. I was a poor shot with a rifle and the ground was soft mud into which one would sink at every step. If the elephant charged and I missed him, I should have about as much chance as a toad under a steam-roller. But even then I was not thinking particularly of my own skin, only the watchful yellow faces behind. For at that moment, with the crowd watching me, I was not afraid in the ordinary sense, as I would have been if I had been alone … The sole thought in my mind was that if anything went wrong those two thousand Burmans would see me pursued, caught, trampled on and reduced to a grinning corpse like that Indian up the hill. And if that happened it was quite probably that some of them would laugh. That would never do."

- Orwell repeatedly states in the text that he does not want to shoot the elephant. In addition, by the time that he has found the elephant, the animal has become calm and has ceased to be an immediate danger. Despite this, Orwell feels compelled to execute the creature. Why?

- Orwell makes it clear in this essay that he was not a particularly talented rifleman. In the excerpt above he explains that by attempting to shoot the elephant he was putting himself into grave danger. But it is not a fear for his "own skin" which compels him to go through with this course of action. Instead, it was a fear outside of "the ordinary sense." What did Orwell fear?

- In colonial Burma a small number of British civil servants, officers and military personnel were vastly outnumbered by their colonial subjects. They were able to maintain control, in part, because they possessed superior firepower -- a point made clear when Orwell states that the "Burmese population had no weapons and were quite helpless against (the elephant)." Yet, Orwell's description of the relationship between the Burmese and Europeans indicates that the division of power was not necessarily that simple. How did the Burmese resist their colonial masters through non-violent means? Ask students to show examples from the text to support their ideas.

- Ask students to explain how they would feel and what they would do were they in Orwell's position.

Activity 4. Reading Between the Lines

"But at that moment I glanced round at the crowd that had followed me. It was an immense crowd… They were watching me as they would watch a conjurer about to perform a trick. They did not like me, but with the magical rifle in my hands I was momentarily worth watching. And suddenly I realized that I should have to shoot the elephant after all. The people expected it of me and I had got to do it; I could feel their two thousand wills pressing me forward, irresistibly. And it was at this moment, as I stood there with the rifle in my hands, that I first grasped the hollowness, the futility of the white man's dominion in the East. Here was I, the white man with his gun, standing in front of the unarmed native crowd—seemingly the leading actor of the piece; but in reality I was only an absurd puppet pushed to and fro by the will of those yellow faces behind. I perceived in this moment that when the white man turns tyrant it is his own freedom that he destroys. He becomes a sort of hollow, posing dummy, the conventionalized figure of a sahib. For it is the condition of his rule that he shall spend his life in trying to impress the "natives," and so in every crisis he has got to do what the "natives" expect of him. He wears a mask, and his face grows to fit it ..."

- In this passage Orwell uses a series of metaphors: "seemingly the lead actor," "an absurd puppet," "he wears a mask," "a conjurer about to perform a trick." as well as comparing the colonial official to a "posing dummy." Ask students to examine this series of metaphors individually as well as collectively in order to find the overarching metaphor for the entire incident.

- If Orwell is "seemingly the lead actor," who is the audience? What is the 'part' he is playing?

- If he is "an absurd puppet," then who is the puppeteer? Does Orwell as the puppet have only one person or group pulling his strings, or is there more than one puppet master?

- How are the metaphors of the "absurd puppet" and the "posing dummy" similar?

- How does his description of himself seemingly the lead actor make this metaphor similar to the "absurd puppet" of the next phrase?

- How is Orwell's description of the colonial official as 'wearing a mask' similar to his own part in this situation as the "lead actor"?

- Each of these metaphors has a theatrical basis. In the following paragraph he even states: "The crowd grew very still, and a deep, low, happy sigh, as of people who see the theatre curtain go up at last, breathed from innumerable throats." What is the 'theater' in which this 'scene' is being 'played'? What is the 'play'?

How does Orwell use metaphors in order to describe a people and a situation geographically and culturally unfamiliar understandable to his readers? Irony

"…The sole thought in my mind was that if anything went wrong those two thousand Burmans would see me pursued, caught, trampled on and reduced to a grinning corpse like that Indian up the hill. And if that happened it was quite probable that some of them would laugh. That would never do."

- When irony is employed by a writer the true intent of his or her words is covered up or even contradicted by the words that are used. Where is irony employed in this excerpt, and what is Orwell's true intent?

- The use of irony often also presumes there being two audiences who will read or hear the delivery of the ironic phrase differently. One audience will hear only the literal meaning of the words, while another audience will hear the intent that lies beneath. Who are the two audiences to whom Orwell is speaking?

Connotation and Denotation

In this section a series of sentences and phrases will be supplied which should provide examples for students to discuss the differences between the connotative and denotative meanings. Explain that denotative meanings are generally the literal meaning of the word, while connotative meanings are the "coloring" attached to words beyond their literal meaning. For example, the "army of people" Orwell refers to in his essay bring to mind not only a large group of people, but also a military and oppositional force. Ask students to explain the connotative and denotative meanings of the following words or phrases using this organizational chart .

- One day something happened which in a roundabout way was enlightening .

- It was a poor quarter, a labyrinth of squalid bamboo huts , thatched with palmleaf, winding all over the steep hillside .

- I marched down the hill, looking and feeling a fool, with the rifle over my shoulder and an ever-growing army of people jostling at my heels.

- They were watching me as they would watch a conjurer about to perform a trick. They did not like me, but with the magical rifle in my hands I was momentarily worth watching.

- He wears a mask , and his face grows to fit it.

Activity 5. Persuasive Perspectives

Orwell was both an accomplished and a prolific essayist whose work covered a large number of topics. Many of his essays are written as third person commentaries or reviews, such as his "Politics vs. Literature: An Examination of Gulliver's Travels." Orwell often chose to include himself in his essays, writing from a first person perspective, such as that employed in one of his most famous essays, "Politics and the English Language."

In these works Orwell uses the first person perspective as a rhetorical strategy for supporting his argument. For example, he opens his 1946 essay "Politics and the English Language" with the following lines:

"Most people who bother with the matter at all would admit that the English language is in a bad way, but it is generally assumed that we cannot by conscious action do anything about it. Our civilization is decadent, and our language- so the argument runs- must inevitably share in the general collapse. It follows that any struggle against the abuse of language is a sentimental archaism … Underneath this lies the half-conscious belief that language is a natural growth and not an instrument which we shape for our own purposes."

In the paragraph which follows the above excerpt Orwell switches from the first person plural to the first person singular. By the second paragraph, however, he has already included his audience in his argument: we cannot do anything; our civilization is decadent. If we disagree with these sentiments, then we are ready to follow Orwell's argument over the following ten pages.

While he does not use the inclusive "we" in "Shooting an Elephant," Orwell's use of the first person perspective is a rhetorical strategy. Discuss with students Orwell's decision to utilize the first person perspective rather than the third person perspective. You might ask question such as:

- How does seeing the incident through both the eyes of Eric Blair, the young colonial police officer, and George Orwell, the reflective essayist, support Orwell's argument?

- How does the story change by having the narrator not only present, but active, in the action of the story?

- How does the use of the first person perspective create a sense of sympathy or understanding for Orwell's position?

- If time permits you may wish to ask students to re-write a section of "Shooting an Elephant" from a different perspective- such as in the third person. What is gained by this shift in perspective? What is lost?

Ask students to write a short essay about one of the following two topics. Students should be sure to support their answers with examples from the text.

- Explain Orwell's use of language, and of rhetorical tools such as the first person perspective, metaphor, symbolism, irony, connotative and denotative language, in his commentary on the colonial project. How does Orwell use language to bring his audience into the immediacy of his world as a colonial police officer?

- The litany of examples of cruelties, insults and moral bankruptcy extend from the Buddhist priests, to the market sellers, the referee, the young British officials who declare the worth of the elephant far above that of an Indian coolie, to Orwell himself. While this essay contains anger and bitterness, is not simply a nihilistic diatribe. In what ways did the project of empire affect all parties involved in the shooting of an elephant?

- George Orwell wrote a second essay called A Hanging about his time as a police officer with the Indian Imperial Police. In addition, Orwell's first novel, Burmese Days , give a fictionalized account of his time in Burma. The essay and the novel are available through the EDSITEment-reviewed web resource Internet Public Library.

- George Orwell was not the only writer to discuss imperialism in his work. Another well known British author, Rudyard Kipling, also made imperialism the focus of some of his works, and the backdrop to many others. Both Orwell and Kipling were born in India to English parents (Kipling was born in Bombay in 1865), and both returned to India after their educations. Despite similar backgrounds their descriptions of empire and their ideas on the moral foundations of the project of empire were quite different. Have students investigate the views of empire by each of these authors through a comparative reading of Orwell's Shooting an Elephant and Kipling's famous poem urging American imperialism in the Philippines, The White Man's Burden . Kipling's poem is available on the EDSITEment-reviewed web resource, History Matters .

Selected EDSITEment Websites

- Burmese history

- History of British Empire in India

- 1897 map of British Empire

- List of British Territories in 1921

- British involvement in Burma

- Biography of George Orwell (Eric Blair)

- Connotation

- Shooting an Elephant

- Burmese Days

- The White Man's Burden

Materials & Media

"shooting an elephant" organizational chart, related on edsitement, animal farm : allegory and the art of persuasion, allegory in painting, fiction and nonfiction for ap english literature and composition, edsitement's recommended reading list for college-bound students.

Colonialism: ”Shooting an Elephant” by George Orwell Essay

The problems of colonialism are generally thought to have not been recognized in earlier times and are thus considered to be only recently discovered. However, there are many texts, both in fiction and non-fiction, that indicate the problems of colonialism were widely recognized and ignored in the face of tremendous profits and the ability to suppress. These texts reveal the inconsistencies of colonialism and its tendency to place the colonized people, regardless of their own values, abilities, and talents, at a somehow sub-human status as if they were naturally intended to serve the desires and greed of the white people who came to rule over them.

Understanding colonialism from the perspective of the ‘dominant’ white man in the colonized country as in Orson Wells’ story “Shooting an Elephant” (1936) reveals how colonialism didn’t necessarily bring about the sense of superiority and greatness expected for the individual white man living in that country.

At the same time, Wells structures this story as a journey story. Journey stories are usually some form of coming-of-age ritual in which the main character learns something significant about himself as a result of some physical journey he’s undertaken. While he doesn’t take any lengthy journeys outside of his familiar region, the narrator of “Shooting an Elephant” relates an incident in which he found himself forced to shoot an elephant by the limitations and expectations of his position as the authoritative white man, learning much about himself in the process.

The story begins with an introduction to the character. It’s told in the first person, so the character speaks directly to the reader as he shares his thoughts about how much he hates his job as an Imperial Policeman. He hates this job because he is obliged to uphold the British persona (that all British are far superior to all India and therefore cannot socialize at any level) even though he doesn’t agree with it and is astonishingly lonely in his present capacity.

While he sympathizes with the situation of the people of India and wants more than anything to be friends with them, the Indian people hate him and constantly bait him by spitting on him, tripping him, and generally finding means of irritating him without actually stepping outside the bounds of their own station in this colonized life. “All I knew was that I was stuck between my hatred of the empire I served and my rage against the evil-spirited little beasts who tried to make my job impossible.”

He is frustrated because he doesn’t have anyone to talk to, and he is being blamed for the actions of his government, something he doesn’t have any control over at all.

Then one day, he is called on to come and take care of a problem. An elephant in musth is running loose in the poor section of town, and they need him to stop it. ‘Musth’ is explained to be something like an animal in heat, ready to copulate with his own species and therefore driven mostly out of his mind by the physical urge until either it is satisfied or the period passes.

The narrator is proud because the common people are confidently turning to him to take care of the problem, but despite his exterior appearance, internally, he isn’t sure if there is anything he can do about it. He rides his pony to the area of town where the elephant is reported to be like a knight riding to the rescue of a fair damsel brandishing his rifle, which is not strong enough to kill the elephant, but he hopes he will make enough noise to frighten it away from the populated areas.

He sends for a stronger gun when he discovers that the elephant has killed a man, but when he sees the elephant, he decides that he doesn’t really need to kill it because it is coming out of musth. “I decided that I would watch him for a little while to make sure that he did not turn savage again and then go home.” The value of a trained elephant was very high when it was alive but very low when dead, and the narrator believes he will be able to point to this fact as a rationale for why the animal wasn’t shot. Although he is sure he is superior in this instant and the one making all the decisions, he is about to learn otherwise.

As he turns to go home, he notices the crowd of excited people who have gathered behind him, waiting either for elephant meat or to see the Englishman get trampled. “Here was I, the white man with his gun, standing in front of the unarmed native crowd—seemingly the leading actor of the piece; but in reality, I was only an absurd puppet pushed to and fro by the will of those yellow faces behind.”

Suddenly, he realizes the true nature of imperialism, wherein seeking to dominate another, the dominator actually only enslaves himself. Although he looked like he was in charge on the outside, he really only had two choices – either kill the elephant and maintain the idea that the British were superior and decisive, or leave the now harmless elephant to wander around until the owner came to get him and give the English empire an association with weakness and indecisiveness in the process. Although the elephant was an expensive piece of equipment, the reputation of the British Empire was more important, so the narrator shoots the elephant.

This short and unusual series of events causes the narrator to reassess his position in life and realize that his position of command is, in reality, a position of service and capitulation to someone else’s set of ideas.

The narrator experiences a loss of self in the face of having to live up to an ideal image of the sahib who must take definitive action rather than simply doing the right thing. The way Wells presents the story indicates that the narrator’s need to shoot the elephant sprung from the need not to make the ‘white man,’ as a social concept, appear foolish rather than from the actual pressure of the crowd itself. Throughout the story, there is a schism between outward appearances and inward realities that highlights the level to which colonization worked to destroy from within on numerous and sometimes unexpected levels.

Pressure Drops

- Who’ll Stop the Rain?

- The Famine-Makers

- It Can Happen to You

- Burning All Illusions

- Everybody Knows

Abolition Everywhere

- Cop Cities, Borders, and Bombs

- ICJ’s Order to Prevent Genocide Applies to the Governments Arming Israel, Too

- Stop Arming Israel

- The Racketeering of State Violence

Trouble Ahead Trouble Behind

- Making Gaza Unliveable

- Israel’s Nuclear Threat: The Dangers Only Multiply

- The Sins of Butte

- Elon Musk and the New Era of Extractive Geopolitics

- Nuclear Warning: A Scientist in Distress

Bottomlines

- Why Should We Give All Our Money to Landlords?

- So Long, and Thanks for All the Hamburgers

- If Capitalism is ‘Natural,’ Why Was so Much Force Used to Build it?

- It’s a Capitalist World

- The Tragedy of Allende-Era Chile: A Strong Start Countered by Imperialist Assault

Empire Burlesque

- Corbyn, Starmer and Labour’s Descent

- Britain in the Bardo

- How Boris Johnson Became a Footnote

- Modern America’s Murderous Apotheosis at Uvalde

- Cheney’s Inferno Comes to Capitol Hill

Borderzone Notes

- Latin America’s New Left

- Religion, Science, Politics

- Virus as Vehicle: How COVID-19 Advances Trump’s White Supremacy Plans

- The War on Indigenous Women

Eurozone Notes

- Just a Little Genocide

- Human Rights and Basic Income

- Halmahera: EVs For Uncontacted People

- West Papua: What the UN Did and Must Undo

- Language, Denaturing, and the Jaguar’s Gaze

Feature Articles

- Buying Democracy with Dirty Money

- Zone of Extermination

- The Banality of Sir Keir Starmer

- Israel’s War Psychosis

- How Israeli Propagandists Reach Journalists

- Larry Hogan’s Dead Chief-of-Staff

- The New York Times’ Bret Stephens, Hasbarist

- What Biden and the Democrats Can Appear to Do About Gaza

- Starvation Games

Culture & Reviews

- Israelism Bucks Blind Faith in Israeli Occupation, Apartheid and “the Jewish Disneyland”

- Los Alamos, Mon Amour: Gone with the Downwind

- Suicide and the Novelist

- Nuclear Power Plant is Ground Zero in SOS – THE SAN ONOFRE SYNDROME

- Bombshells: Barbie and the Nuclear Age

CounterPunch Magazine Archive

Read over 400 magazine and newsletter back issues here

Support CounterPunch

Make a tax-deductible monthly or one-time donation and enjoy access to CP+. Donate Now

Support our evolving Subscribe Area and enjoy access to all Subscribers content. Subscribe

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

‘I had got to escape not merely from imperialism but from every form of man’s dominion over man.’ Research George Orwell’s essays, correspondence and full-length texts in order to establish the background to his anti-imperialist views.

In 1936, George Orwell wrote that he ‘had got to escape not merely from imperialism but from every form of man’s dominion over man’ – strong words indeed. This research reviews those early works that reflect his Empire experiences and notes how his anti-imperialism developed. Orwell’s time as a policeman in Burma in the 1920s caused him to rethink many of the principles that had resulted from his colonial family background, class, education and Englishness. His eventual hatred of imperialism stimulated Orwell to absorb himself in a lifetime’s literary campaign on behalf of victims of oppression whether that stemmed from the exploitation of subject races by imperialist Britain, the inhumane treatment of the working-classes by capitalist industrialists or the cruel and corrupt wielding of absolute power by despotic extremist regimes.

Related Papers

Cross-Cultural Studies Journal Vol. 28

Pavan Malreddy

Journal of East-West Thought No.3, Vol.13, Fall

Subham Mukherjee

George Orwell's Shooting an Elephant (1936) introduces to the readers the colonial experiences of the author during his time in Burma. Thinking through the author's conflicting ideology and his contradictory identities, this paper argues that beneath the apparent dichotomy, Orwell maintains an underlying complicity in his sentiments of anti-colonialism. In his existential and moral suffering, the author tacitly reproduces the colonial subjects and reinforces the production of alterity, naturalizing the white man's burden. The paper explores the colonial assimilation of the colonizer and the colonized and how it survives in the intellectual recesses of an anti-imperialist. Referring to Althusser's conceptualization of the mechanism of ideology, we critically reexamine the molecular nature of the colonial and the ideological apparatus and how it discreetly constructs ideological complicity, which dialectically defends the colonial subjectivity and the loss of Self through a logic of colonial exclusion.

Douglas Kerr

This essay argues for a close relationship and intriguing similarities between George Orwell and Rudyard Kipling, writers a generation apart, who are usually thought of as occupying opposite ends of the political spectrum, with Kipling’s wholehearted conservative belief in the British Empire standing in contrast to Orwell’s socialist hatred of the same institution. Yet these two great writers of fiction and journalism have much in common: born in India into what Orwell called “the ‘service’ middle class”, both had their political and intellectual formation in the East. Empire made Kipling proud and it made Orwell ashamed, but their imperial experience overseas gave both of them a global vision, which each in turn tried to share with their readers at home who understood too little, they felt, of Britain’s global responsibilities (Kipling) or her reliance on a “coolie empire” (Orwell). This essay examines the global vision of both writers, and the highly partial perspective conferred on it by the optic of empire. It does so by looking at two journalistic or “travel writing” texts about other people’s empires: Kipling’s account in From Sea to Sea of a visit to China in 1889, and Orwell’s essay “Marrakech”, written during his stay in French Morocco in 1938-39.

Journal of World-Systems Research

Brendan McQuade

George Orwell is one the best known and highly regarded writers of the twentieth century. In his adjective form— Orwellian—he has become a “Sartrean ‘singular universal,’ an individual whose “singular” experiences express the “universal” character of a historical moment. Orwell is a literary representation of the unease felt in the disenchanted, alienated, anomic world of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. This towering cultural legacy obscures a more complex and interesting legacy. This world-system biography explains his contemporary relevance by retracing the road from Mandalay to Wigan that transformed Eric Blair, a disappointing-Etonianturned- imperial-policeman, into George Orwell, a contradictory and complex socialist and, later, literary icon. Orwell’s contradictory class position—between both ruling class and working class and nation and empire—and resultantly tense relationship to nationalism, empire, and the Left makes his work a particularly powerful exposition of the tension between comsopolitianism and radicalism, between the abstract concerns of intellectuals and the complex demands of local political action. Viewed in full, Orwell represents the “traumatic kernel” of our age of cynicism: the historic failure and inability of the left to find a revolutionary path forward between the “timid reformism” of social democrats and “comfortable martyrdom” of anachronistic and self-satisfied radicals.

George Orwell Studies

Darcy Moore

Orwell and Empire Douglas Kerr Oxford University Press, 2022, pp 240 ISBN: 9780192864093 (hbk)

Imperialism has been the most powerful force in world history over last four or five centuries. The world has moved from the colonial to post-colonial era or neoimperialism. Throughout the period, the imperialists have changed their grounds and strategies in imperialistic rules. But the ultimate objective has remained the same-to rule and exploit the natives with their multifaceted dominance-technological, economic and military. Through dominance with these, they have been, to a great extent, successful in establishing their racial and cultural superiority. George Orwell is popularly known to be an anti-imperialist writer. This paper, I believe, will lead us to an almost different conclusion. Here, we discover the inevitable dilemma in a disguised imperialist. We discover the seeds of imperialism under the mask of anti-imperialism. In this regard, it studies his revealing short story "Shooting an Elephant". It also humbly approaches to refute Barry Hindess' arguments supporting neoimperialism.

International Journal of Arabic-English Studies

Abdullah Shehabat

Journal of British Studies

Daniel Ritschel

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES & SOCIAL STUDIES

YİĞİT SÜMBÜL

The British rule in Burma as a colony lasted over sixty years in which there took place many disputes between the sides and led to the separation of the latter from the British in 1886 and total independence in 1948. The British preserved their activism in the territory for much more, covering the time period in which a famous anti-imperialist British writer of fiction, George Orwell, worked as a police officer around the area. The colonial domination of England over Burma was narrated by Orwell in his famous essay "Shooting an Elephant", one of his various political essays reflecting his anti-capitalist viewpoint. The narrator in the essay is usually thought to be Orwell himself, as he worked in Burma as a British officer for a couple of years. It is widely known that Orwell spent some time in the place as a police officer, similar to that of the narrator, but "the degree to which his account is autobiographical is disputed, with no conclusive evidence to prove it to be fact or fiction" (Crick, 1981:1). On the surface level, the essay centers on the inner conflict of a white European police officer in Burma regarding the killing of an elephant which raided the bazaar and caused material damage. It is not known whether Orwell himself had such an incident with an elephant, but the vividness of the descriptions strengthen such a claim. On a deeper level of understanding, the incident of shooting the elephant metaphorically represents the macrocosm of British imperialism and colonialism over the east. Imperialism, here, refers to "a state of mind, fuelled by the arrogance of superiority that could be adopted by any nation irrespective of its geographical location in the world" (Chy, 2006:55). In this respect, the essay gets a much more critical depth displaying the stance of the author against British colonialism and imperialism. As a short synopsis of what the author tells in the essay, before unveiling the metaphorical meaning, it is necessary to mention that the story takes place in Moulmein, Lower Burma, which was one of the British colonies and later annexed into British India. The narrator, who is working in the colony as a police officer, is asked to take care of a stray elephant which ravages a bazaar; and the narrator gets this incident as a responsibility on his own shoulders as a matter of 'White Man's Burden'. With the tension created by the thousands following him, believing he is going to shoot the elephant, the officer feels that it is now obligatory to kill the animal in order not to harm British reputation as the superior hand in the imperial business. As Taylor puts it, "he shot it, because the huge crowd expected him to and he had 'to impress' the natives" (Taylor and Cumming, 1993). The narration turns into an interior monologue of the author as he dives deeper into his conscience and dilemmas in killing the elephant, revealing the whole colonial nature of the feeling of guilt and responsibility. The essay takes a political stance, however, from the very opening lines referring to the relationship between the colonizer and the colonized. In a self-conscious and self-critical attitude, the narrator admits that he "was hated by large numbers of people" (2003:1), due to his position as an outsider coming and reordering the pre-established norms and laws in the Burmese society. However, the approach of the narrator to the situation is of an opposition against the colonial-imperial rule of his own nation, and the essay functions as a post-colonial text, using the Western language, forms and voice against itself. The scene is described, Abstract: Generally known for his politically concerned literary pieces, Eric Arthur Blaire, who uses the pen name George Orwell during his short-lived literary career, is the author of various novels, short stories, essays and a small number of poems; placing him among the luminaries of the 20 th century literature. Orwell's political writings shed light upon popular political issues of his time, ranging from colonialism and imperialism to authoritarian regimes and socialism. Besides his artistic career, Orwell has always been subject to critical dispute upon his commissions as a police officer in the British colony of Burma, during which he conceived the ideas for his critical essay, "Shooting an Elephant". The aim of this article is to discuss Orwell's political essay "Shooting an Elephant" in the light of post-colonial literary criticism, emphasizing the possible interpretations that the elephant in the narrative allegorically stands for imperialism and the reactions of the officer, who gives voice to Orwell's own critical stance towards British colonial rule over the Burmese, reinforce the self-depreciating nature of colonialism on a much broader universal scale. Consequently, the present study concludes that Orwell's experiences in the British colony foreshadows the forthcoming end of British imperialism, not only in Burma, but in other colonies throughout the world as well.

RELATED PAPERS

Ulrich Gehmann

Brazilian Journal of Physics

Elder A de Vasconcelos

Nahwa Travel

Paket wisata Travel Malang Surabaya

Riam Badriana

prathibha bandaru

Bruna Carolini Barbosa

Palabra Clave - Revista de Comunicación

Felipe Marañón

Scientific Data

Tatiana Akimova

Andi Rahman

Bruniana & Campanelliana

Simone Guidi

E3S Web of Conferences

Ulan Tlemissov

Onomázein Revista de lingüística, filología y traducción

Norma Manjarrés

Sebastián Ramírez López

Srinath Kamineni MD, FRCS-Orth

ayush tyagi

The Journal of Immunology

Mitchell Kronenberg

Revista Universo Contábil

Andréia Oliveira Santos

Stato, Chiese e Pluralismo Confessionale

nicola colaianni

Corinne Autant-Bernard

Behavioral Ecology

Marco Rodriguez

Zagazig Journal of Agricultural Research

Narges Hamed Abdo

Miscellanea Historico-Archivistica, t. 22, 2015, s. 169-202

Jacek Krochmal

jhkghjf hfdgedfg

FEMERIS: Revista Multidisciplinar de Estudios de Género

Sergio Alcina

Murat Bardakçı ile Hürriyet Tarih

Mustafa Birol Ülker

See More Documents Like This

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Burma Sahib by Paul Theroux review – how Eric Blair became George Orwell

The evils of empire are brought to life in this fascinating imagining of Orwell’s days as a colonial policeman, but the perspective of Burmese people is sidelined

G eorge Orwell’s years as a colonial policeman in Burma in the 1920s preoccupied him for the rest of his life. Straight out of Eton, he was thrown into a world that mirrored the public school with its rivalries and floggings; except that now it was the Burmese people who were being flogged. He wrote about it repeatedly: in his 1934 novel Burmese Days, several essays, and passages devoted to Burma in The Road to Wigan Pier. Even on his deathbed he was writing notes for a novella about Burma entitled A Smoking Room Story. Now, Paul Theroux has taken on this material, with a novel that explores Burma as the place where Eric Blair became George Orwell .

There has been so much written about Orwell recently, from DJ Taylor’s casually magisterial biography , to Anna Funder’s intricately daring book about his first wife , to Sandra Newman’s high-wire feminist retelling of Nineteen Eighty-Four. In her 2005 travel memoir Finding George Orwell in Burma , Emma Larkin discovers that Orwell’s great uncle had a Burmese mother.

This is a risky project for Theroux; there is always the danger in novels about writers that the dialogue becomes an embarrassing parody. He avoids this by focusing on Orwell’s blankness of character at this age. The dialogue is convincing because the inner Orwell remains hidden and the things he says are conventional and terse. Theroux uses this to suggest that all the time a secret self was developing: “his other self, the restless inquisitor, the doubter, the contrarian”.

The secret self is Orwell the writer, and, in the end, Theroux is writing for Orwell connoisseurs. We know very little about what Orwell was reading during these years, but Theroux imagines it all for him, moving from Wells to Lawrence to Forster. Theroux shows how these literary influences might combine with everyday experience to create the writer of Burmese Days. Indeed, phrases from the novel are seen to have their genesis in conversations here.

Beyond its interest for Orwell enthusiasts, I couldn’t decide if this book succeeded as a novel. It is rather fascinating in its portrait of Orwell’s ambivalence towards the empire he reviles and serves. If Burmese Days doesn’t have the reach and depth of Orwell’s best work, it’s because he was dishonest at this point in making his autobiographical hero a convinced rebel – “notoriously a bolshie in his opinions”. In fact, at the time Orwell had been more confused. One ex-Etonian visitor reported Orwell revelling in being a servant of the crown, and in his 1936 essay Shooting an Elephant he wrote, repellently, that “in the end the sneering yellow faces of young men that met me everywhere, the insults hooted after me when I was at a safe distance, got badly on my nerves” (the “yellow faces” are bad enough; “sneering” turns the Burmese into Eton schoolboys).

Theroux takes these admissions and shows Orwell veering between ethical disdain and appalling complicity. We see Orwell presented with a series of moral tests – pulling a dead man’s ring off his finger and finding the whole finger comes with it; ordering the hanging of a man he knows to be innocent. When an elephant goes on the rampage and kills a man, he is faced with the appalling prospect of shooting it, largely to pacify the jeering onlookers because “no one in that crowd … would have respected the Burma sahib for doing nothing”.

Orwell fails as a policeman and he fails morally, with each test becoming more disillusioned with empire, yet more implicated in its methods. Assaulted by schoolboys, he longs for “a dah, to swipe at their skinny arms and slash their faces”. Inspired by Larkin’s research, Theroux invents a half-Burmese first cousin for Orwell, which works as a thought experiment by revealing Orwell’s embarrassed, small-minded racism (“the young half blood calling his mother Aunt Ida”).

Theroux brings the empire and its evils alive as a day-by-day experience. This is what writing the book as a novel enables him to do, in a way that more abstract academic discourses around colonialism can’t. But if it becomes most compellingly a book about empire, then that is also where its perspective is most limited. In that line about “yellow faces” Orwell was luxuriating in his own self-inculpation, and this is what Theroux’s Orwell does throughout. The problem is that at this point in history, the stories about Burma we need to read are not stories about the intricate feelings of the white men who colonised it.

after newsletter promotion

The novel doesn’t seem especially troubled by this. The Burmese are here merely as supporting characters, with the women as exotic stereotypes, whose slippery delicacy contrasts with the no less stereotypical but more richly Lawrentian memsahib who orders Orwell into bed as an alternative to “frigging” herself.

I was left comparing Burma Sahib to Theroux’s 1981 novel The Mosquito Coast – at its heart a story about an anarchic empire builder with overreaching ambitions. The Mosquito Coast is also about the complex feelings of white men in the jungle, but it has aged well because of its madness and extremity. The portrait of white male angst there ballooned into a tragic portrayal of American fatherhood, and of America itself as doomed by the awful power of frontier fathers. The writing in Burma Sahib is in places just as brilliant, but it is precisely the exquisite rightness page by page that reminds us that Theroux now has less compelling things to say.

Burma Sahib by Paul Theroux is published by Hamish Hamilton (£20). To support the Guardian and the Observer buy a copy at guardianbookshop.com . Delivery charges may apply.

- George Orwell

- Paul Theroux

Most viewed

- About George Orwell

- Partners and Sponsors

- Accessibility

- Upcoming events

- The Orwell Festival

- The Orwell Memorial Lectures

- Books by Orwell

Essays and other works

- Encountering Orwell

- Orwell Live

- About the prizes

- Reporting Homelessness

- Enter the Prizes

- Previous winners

- Orwell Fellows

- Introduction

- Enter the Prize

- Terms and Conditions

- Volunteering

- About Feedback

- Responding to Feedback

- Start your journey

- Inspiration

- Find Your Form

- Start Writing

- Reading Recommendations

- Previous themes

- Our offer for teachers

- Lesson Plans

- Events and Workshops

- Orwell in the Classroom

- GCSE Practice Papers

- The Orwell Youth Fellows

- Paisley Workshops

The Orwell Foundation

- The Orwell Prizes

- The Orwell Youth Prize

- The Orwell Council

The Orwell Foundation is delighted to make available a selection of essays, articles, sketches, reviews and scripts written by Orwell.

This material remains under copyright in some jurisdictions, including the US, and is reproduced here with the kind permission of the Orwell Estate . All queries regarding rights should be addressed to the Estate’s representatives at A. M. Heath literary agency.

The Orwell Foundation is an independent charity – please consider making a donation to help us maintain these resources for readers everywhere.

Sketches For Burmese Days

- 1. John Flory – My Epitaph

- 2. Extract, Preliminary to Autobiography

- 3. Extract, the Autobiography of John Flory

- 4. An Incident in Rangoon

- 5. Extract, A Rebuke to the Author, John Flory

Essays and articles

- A Day in the Life of a Tramp ( Le Progrès Civique , 1929)

- A Hanging ( The Adelphi , 1931)

- A Nice Cup of Tea ( Evening Standard , 1946)

- Antisemitism in Britain ( Contemporary Jewish Record , 1945)

- Arthur Koestler (written 1944)

- British Cookery (unpublished, 1946)

- Can Socialists be Happy? (as John Freeman, Tribune , 1943)

- Common Lodging Houses ( New Statesman , 3 September 1932)

- Confessions of a Book Reviewer ( Tribune , 1946)

- “For what am I fighting?” ( New Statesman , 4 January 1941)

- Freedom and Happiness – Review of We by Yevgeny Zamyatin ( Tribune , 1946)

- Freedom of the Park ( Tribune , 1945)

- Future of a Ruined Germany ( The Observer , 1945)

- Good Bad Books ( Tribune , 1945)

- In Defence of English Cooking ( Evening Standard , 1945)

- In Front of Your Nose ( Tribune , 1946)

- Just Junk – But Who Could Resist It? ( Evening Standard , 1946)

- My Country Right or Left ( Folios of New Writing , 1940)

- Nonsense Poetry ( Tribune , 1945)

- Notes on Nationalism ( Polemic , October 1945)

- Pleasure Spots ( Tribune , January 1946)

- Poetry and the microphone ( The New Saxon Pamphlet , 1945)

- Politics and the English Language ( Horizon , 1946)

- Politics vs. Literature: An examination of Gulliver’s Travels ( Polemic , 1946)

- Reflections on Gandhi ( Partisan Review , 1949)

- Rudyard Kipling ( Horizon , 1942)

- Second Thoughts on James Burnham ( Polemic , 1946)

- Shooting an Elephant ( New Writing , 1936)

- Some Thoughts on the Common Toad ( Tribune , 1946)

- Spilling the Spanish Beans ( New English Weekly , 29 July and 2 September 1937)

- The Art of Donald McGill ( Horizon , 1941)

- The Moon Under Water ( Evening Standard , 1946)

- The Prevention of Literature ( Polemic , 1946)

- The Proletarian Writer (BBC Home Service and The Listener , 1940)

- The Spike ( Adelphi , 1931)

- The Sporting Spirit ( Tribune , 1945)

- Why I Write ( Gangrel , 1946)

- You and the Atom Bomb ( Tribune , 1945)

Reviews by Orwell

- Anonymous Review of Burmese Interlude by C. V. Warren ( The Listener , 1938)

- Anonymous Review of Trials in Burma by Maurice Collis ( The Listener , 1938)

- Review of The Pub and the People by Mass-Observation ( The Listener , 1943)

Letters and other material

- BBC Archive: George Orwell

- Free will (a one act drama, written 1920)

- George Orwell to Steven Runciman (August 1920)

- George Orwell to Victor Gollancz (9 May 1937)

- George Orwell to Frederic Warburg (22 October 1948, Letters of Note)

- ‘Three parties that mattered’: extract from Homage to Catalonia (1938)

- Voice – a magazine programme , episode 6 (BBC Indian Service, 1942)

- Your Questions Answered: Wigan Pier (BBC Overseas Service)

- The Freedom of the Press: proposed preface to Animal Farm (1945, first published 1972)

- Preface to the Ukrainian edition of Animal Farm (March 1947)

External links are being provided for informational purposes only; they do not constitute an endorsement or an approval by The Orwell Foundation of any of the products, services or opinions of the corporation or organisation or individual. The Foundation bears no responsibility for the accuracy, legality or content of the external site or for that of subsequent links. Contact the external site for answers to questions regarding its content.

We use cookies. By browsing our site you agree to our use of cookies. Accept

The Failed Saint: On George Orwell’s India

By jason christian january 21, 2024.

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2024%2F01%2FMA_I120489_TePapa_Ruins_full.jpg)

For five years I had been part of an oppressive system, and it had left me with a bad conscience. Innumerable remembered faces—faces of prisoners in the dock, of men waiting in the condemned cells, of subordinates I had bullied and aged peasants I had snubbed, of servants and coolies I had hit with my fist in moments of rage (nearly everyone does these things in the East, at any rate occasionally: Orientals can be very provoking)—haunted me intolerably. I was conscious of an immense weight of guilt that I had got to expiate.

It is curious, but till that moment I had never realized what it means to destroy a healthy, conscious man. When I saw the prisoner step aside to avoid the puddle, I saw the mystery, the unspeakable wrongness, of cutting a life short when it is in full tide. This man was not dying, he was alive just as we were alive [...] and in two minutes, with a sudden snap, one of us would be gone—one mind less, one world less.

LARB Contributor

LARB Staff Recommendations

Orwell’s many-thorned bomb shelter: a conversation with rebecca solnit.

Andrea Hoag interviews Rebecca Solnit about her new book on George Orwell, “Orwell’s Roses.”

Andrea Hoag Oct 13, 2021

The Odor of Mortality: On John Sutherland’s “Orwell’s Nose”

In "Orwell's Nose," John Sutherland captures Orwell's essence in a brief 240 pages better than most biographers do in 600. But is it enough?

Andrew Fedorov Aug 29, 2016

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

Advertisement

Supported by

Before He Was George Orwell, He Was Eric Blair, Police Officer

Paul Theroux’s new novel, “Burma Sahib,” explores the writer’s formative experiences in colonial Myanmar.

- Share full article

By William Boyd

William Boyd’s most recent novel is “The Romantic.”

- Apple Books

- Barnes and Noble

- Books-A-Million

When you purchase an independently reviewed book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission.

BURMA SAHIB , by Paul Theroux

George Orwell died of tuberculosis in 1950, at the age of 46. Yet today, over 70 years later, his long shadow remains as dark and well defined as ever, particularly in Britain, where he is enlisted and quoted as an authority as often as Shakespeare, Winston Churchill or the Bible. The word “ Orwellian ” is as omnipresent as “Kafkaesque.” His two dystopian novel-allegories — “Animal Farm” and “1984” — have sold in the millions around the world.

Orwell’s influence extends far past his literary reputation. He has become a kind of posthumous public intellectual, and it’s hard to imagine other figures in literature who command the same import as a sage and a seer. Albert Camus, perhaps? Henry David Thoreau? Walt Whitman? Tolstoy? In any event, the Orwell industry is thriving. Almost everything that Orwell wrote seems to be in print. Biographies of the man abound.

But there is one area of his life that is relatively unexplored and full of baffling gaps, not to say mystery. In 1922, a 19-year-old man named Eric Blair, fresh from his elite private school, Eton College, traveled to what was then the British colony of Burma (present-day Myanmar) to train and work as a colonial police officer, as many middle-class Englishmen did in those days when a job in the colonies was more easily had than one at home. He was still several years removed from becoming “George Orwell” by adopting the nom de plume that would carry his legacy.

Paul Theroux has exploited this biographical lacuna with great shrewdness and gusto. He not only knows all the details of Orwell’s life but he also knows Burma well, and his fictional account of Blair’s life there from 1922 to 1927 is a valid and entirely credible attempt to add flesh to the skeletal facts we have of this time.

The narrative follows Blair’s itinerary through Burma — the spells passed in Rangoon and postings to various provincial towns and districts — and it also draws from his 1934 novel, “Burmese Days,” and the celebrated essays “ A Hanging ” and “ Shooting an Elephant .” Theroux reimagines these familiar scenes with gritty aplomb. If you are going to write fiction about a real person, then there is no point in simply reiterating the received wisdom about that person’s nature or character. He or she must be rendered idiosyncratically; the curated myth must be robustly de-mythologized or else the endeavor is pointless.

Theroux is very much up to the task. His Blair is a somewhat tormented soul, naïve and out of his depth, increasingly uneasy about his responsibilities as a police officer and increasingly repelled by the snobberies and barbarities of colonial life. He’s also a victim of the arrogant and resentful bullies who are his superiors. His thoughts, as imagined and detailed by Theroux, are full of anguished questions and examinations of his feelings and motives.

This Blair also has an active sex life with local prostitutes and colonial wives. We know nothing of Orwell’s sexual activities during his four and a half years in Burma but everything Theroux writes reeks of plausibility. The deadening torpor of colonial life, its petty jealousies, its social hierarchies, its sexual hypocrisies, its unthinking racism all ring exceptionally true.

Theroux, of course, has a parallel reputation as one of our greatest travel writers, and the Burma that he conjures in these pages is wonderfully present in lush and dense prose: