We use cookies to enhance our website for you. Proceed if you agree to this policy or learn more about it.

- Essay Database >

- Essays Samples >

- Essay Types >

- Report Example

Homicide Reports Samples For Students

4 samples of this type

Do you feel the need to check out some previously written Reports on Homicide before you start writing an own piece? In this open-access catalog of Homicide Report examples, you are granted an exciting opportunity to explore meaningful topics, content structuring techniques, text flow, formatting styles, and other academically acclaimed writing practices. Implementing them while composing your own Homicide Report will definitely allow you to finalize the piece faster.

Presenting high-quality samples isn't the only way our free essays service can help students in their writing ventures – our experts can also compose from scratch a fully customized Report on Homicide that would make a solid basis for your own academic work.

Good Procedure For Solving The Case Report Example

Final project: cold case arrest warrant report.

Final Project: Cold Case Arrest Warrant Report This report represents an outline of a homicide investigation. The first section presents the action plan for solving the case. The report also provides a summary of the homicide, armed robbery, and witness statements, and a briefing of evidence and forensic reports. Additionally, it describes the criteria for decision-making and determination of facts regarding the homicide. The report indicates what the investigating officer concludes about the case, in an attempt to obtain an arrest warrant for the suspect.

Free Labeling Theory Report Example

Introduction 3.

History of Labeling Theory 4 Critiques of Labeling Theory 5 How Do Current Criminal Justices Policies Demonstrate an Application of the Theory to Practice? 7 Reflection 8 Conclusion 9

Reference List 10

Government measures to decrease the level of robbery report examples, criminal law.

Don't waste your time searching for a sample.

Get your report done by professional writers!

Just from $10/page

Stand Your Ground Law Report Sample

Password recovery email has been sent to [email protected]

Use your new password to log in

You are not register!

By clicking Register, you agree to our Terms of Service and that you have read our Privacy Policy .

Now you can download documents directly to your device!

Check your email! An email with your password has already been sent to you! Now you can download documents directly to your device.

or Use the QR code to Save this Paper to Your Phone

The sample is NOT original!

Short on a deadline?

Don't waste time. Get help with 11% off using code - GETWOWED

No, thanks! I'm fine with missing my deadline

Research Paper

Homicide research paper.

This sample Homicide Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Like other free research paper examples, it is not a custom research paper. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our custom writing services and buy a paper on any of the criminal justice research paper topics . This sample research paper on homicide features: 5400+ words (19 pages), an outline, APA format in-text citations, and a bibliography with 23 sources.

I. Introduction

Ii. homicide trends over time, a. the crime drop, b. explanations for the crime drop, iii. race-specific homicide trends, a. divergence or convergence, iv. intimate partner homicide trends, a. exposure reduction, b. backlash or retaliation, c. economic deprivation, v. conclusion.

Criminal homicide is classified by the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program as both murder and nonnegligent manslaughter or as manslaughter by negligence. Homicide research generally examines murder and nonnegligent manslaughter, defined as the willful killing of one by another. Justifiable homicide, manslaughter caused by negligence, suicide, or attempts to murder are not included in this definition. For UCR purposes, justifiable homicide is limited to the killing of a felon by an officer in the line of duty or the killing of a felon, during the commission of a felony, by a private citizen. Manslaughter by negligence is the killing of a human being by gross negligence.

When researching homicide, scholars generally utilize two national sources of homicide data—the Uniform Crime Reporting Program of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and mortality files from the Vital Statistics Division of the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). These two data sources vary greatly in the information collected.

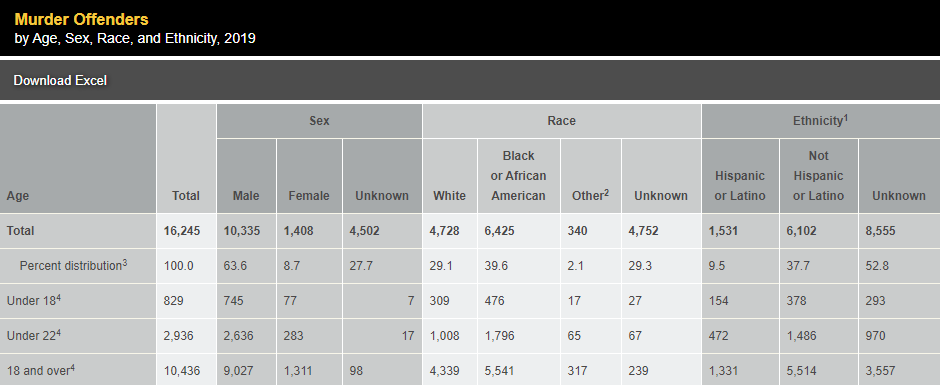

The UCR is an official source of crime statistics based on reported crimes. That is, it is based on the number of arrests voluntarily reported to the FBI by law enforcement agencies. These crimes include murder, rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, larceny-theft, vehicle theft, and arson. In addition to monthly criminal offense information compiled for UCR purposes, law enforcement agencies submit supplemental data to the FBI on homicide. Supplemental Homicide Reports (SHRs) contain supplemental information on homicide incidents. SHRs include detailed, incident-level data on nearly all murders and nonnegligent manslaughters that have occurred in the United States in a given year. These reports contain information for each homicide incident, including information on trends, demographics of persons arrested, and the characteristics of the homicide (i.e., demographics of victims, victim–offender relationships, weapon used, and circumstances surrounding the homicide).

Though a rich source of homicide data, the UCR Program has weaknesses of which researchers are well aware. Missing information regarding the homicide incident is problematic in the UCR and probably its main weakness. This may be due to the fact that participation by police agencies in the UCR Program is completely voluntary. Therefore, some law enforcement agencies fail to report their homicide incidents to the FBI or fail to fully record all relevant information. Despite this fact, official sources like the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) have found that the SHRs are just over 90% complete. Though the coverage is high, there are still a number of homicides that go unaccounted for. Some researchers have taken steps to correct for underreporting by law enforcement agencies by statistically adjusting for the total number of homicide incidents reported to the UCR (see Fox, 2004). The ability to adjust for missing data based on known homicide cases has increased the popularity of this data source among researchers. However, one growing problem, particularly with homicide offender information, is the increase in the number of unsolved or uncleared murders by police agencies. Stranger homicides take longer to clear by arrest and therefore often get submitted as “unknown.” Ignoring homicides with missing offender information understates homicide offending. Thus, there is greater dependency on researchers to use weighting strategies that statistically adjust for missing offender data (see Fox, 2004, for a detailed discussion of this specific issue).

The mortality reporting system is far simpler compared to the UCR. In this system, homicide information is gathered by medical examiners in the completion of standardized death certificates. Once verified, death certificates are entered into a national mortality dataset by the NCHS. According to the NCHS, these data represent at least 90% of all homicides that have occurred in the United States. This type of data contains information on the victim of the homicide. Victim information includes demographics, occupation, education, time of death, place of death, and cause of death. Just as seen for the UCR, there are weaknesses in mortality data such as omissions and underreporting. Unfortunately, for a variety of reasons not all death certificates are received by NCHS, and in some incidents information on death certificates is not entered into mortality figures. In addition, unlike with the UCR, offender information is not available and unable to be collected. Even with these notable limitations, homicide remains the most accurately measured and reported offense relative to other types of criminal offenses.

One of the reasons these data issues are so critical is that researchers and policymakers are interested in documenting and understanding the changes in homicide offending over time. That is, researchers and policy makers alike want to know how much homicide offending is occurring, why homicides occur and if the level of homicide offending is increasing or decreasing in certain areas (i.e., states, cities, or counties) over time.

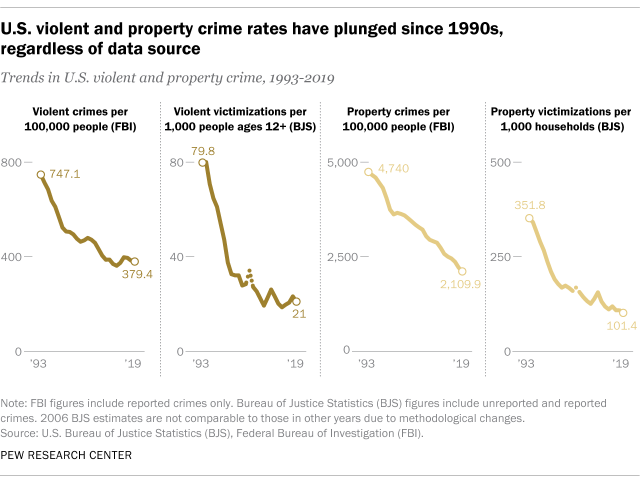

One of the most remarkable findings in the study of urban violence is that homicide rates fell sharply in U.S. cities in the 1990s. In fact, homicides plunged to their lowest point in 35 years, making this drop critical to any discussion of homicide. That is, any effort to understand homicide requires an examination of homicide trends over time, particularly this rather remarkable, unexpected crime drop of the 1990s. To that end, this research paper will provide statistical information on urban homicide trends since the 1980s, drawing specifically on SHRs. After documenting some important changes, some of the leading explanations for the crime drop will then be outlined, to give the reader an understanding of the level and nature of work being conducted to understand this precipitous decline.

Researchers use time series data of total homicide rates to document the crime drop. As stated in the introduction, homicide is the most accurately measured and reported offense, making it the best benchmark when trying to illustrate changes in criminal offending over time. In addition, homicide is the most serious crime, leading it to be the most widely used among academicians. For these reasons and others, homicides provide a useful and accurate account of crime trends.

Time series data show that homicides averaged 19.0 per 100,000 population in 1980, and rates tended to fluctuate between 19 and 22.5 until 1991, when homicides peaked (22.5 per 100,000 population). That is, examination of SHR data reveals that homicides dropped by 20% from 1980 to 1985, but then rose by 47% from 1985 to 1991. Starting in 1991, homicides started a steady decline until 2000, falling to their lowest rate in 2000, or a drop of 46%. Since 2000, the rate of homicide has been largely stable until 2006 or so when an increase was observed. Overall, SHR data have documented a dramatic rise in homicides in the late 1980s, followed by the precipitous decline in the 1990s. This incredible crime drop has gained widespread attention as scholars have searched for answers (FBI, 2008).

The drop in homicide rates occurred without warning, leading to an explosion of newspaper articles, TV reports, and other media accounts. Scholarly attention soon followed with a list of potential explanations, including greater police presence, prison expansion, reduced handgun availability, tapering drug (specifically crack cocaine) markets, gains in the economy, and age shifts in the population (Blumstein & Wallman, 2001). While the list continues to grow, some of the explanations receiving the greatest attention in the literature are outlined below.

Rise in Imprisonment Rates . An understanding of the changes in crime rates cannot occur without some consideration of the political and legal context of the time period. The enormous growth in “get tough on crime” policies that began in the 1970s is no exception. The expansion of the incarcerated population started in the mid-1970s, and by 2000 more than 2 million persons were incarcerated— 4 times the prison population of 1970. Because the rise in incarceration rates corresponds closely with the decline in homicide rates, some researchers linked the two. For example, while homicides were dropping from 1991 to 2001 in large cities, the Bureau of Justice Statistics reports incarceration rates rose by 54.2% during this time period (a rate change of 310 to 478 per 100,000 residents nationally). The rise in incarceration, backed by structured sentencing (i.e., “get tough” on violent and drug-related criminal offenders) and other conservative criminal justice policies, is one of the longest trends documented in the literature. Given the steady and prolonged trends in both rates of violence and incarcerations, it is not surprising that a number of scholars argue for the association between the two.

Increase in Police Presence . One response to rising crime rates is to hire more police officers. There is evidence that this was indeed a response to crime trends based on annual figures in the UCR. These reports tell of more police on the street, particularly in the 1990s when the FBI reports an extra 50,000–60,000 officers nationally (Levitt, 2004). On average, the police force size was 236.1 per 100,000 city residents in 2000, up from 206.9 per 100,000 persons in 1980 in large U.S. cities (Parker, 2008).These trends provide scholars with reasons to argue that increasing police presence is a likely predictor of the crime decline in the 1990s.

Diminishing Drug Markets . A link between violence and illicit drug markets is another major theme in the crime drop debate. Crack cocaine markets, which grew throughout the mid-1980s and peaked in the early 1990s, were related to homicide trends during this same time period (Blumstein, 1995). In fact, researchers found that drug markets contribute to violence, and studies have pointed to crack cocaine patterns specifically as related to trends in urban violence (Blumstein & Rosenfeld, 1998; Cook & Laub, 1998; Goldstein 1985). While determining how to best capture the impact of drug markets has hindered much of this research, police arrests for drug (specifically cocaine) sales represent one way to tap the level of drug activity in a given area or city. The UCR has shown that drug arrests for sales/manufacturing have exploded, growing by two and a half times from 1982 to 2003 alone (from 137,900 to 330,600). Thus, evidence of the waning crack market in the 1990s, or at least the growing enforcement of drug sales in recent times, has placed drug markets at the forefront of the crime drop debate.

Improving Economy of the 1990s . The link between economic factors and crime cannot be understated, so it comes as no surprise that the economic improvements of the 1990s have gained attention as a plausible explanation for the crime decline. In fact, in accord with labor statistics, the unemployment rate rose during the recessions of the early 1980s and early 1990s, recovering after both periods. On the other hand, the unemployment rate steadily declined throughout the 1990s, where employment gains for males and females correspond to the crime drop of this period. The unemployment rate alone fell from 6.8 in 1991 to 4.8 in 2001 (a drop of 30% in 10 years). Other economic performance indicators suggest better times for many Americans in the 1990s, as well as growth in major industries like information technology and services. Given that the 1990s mark a time of sustained economic growth and prosperity, these economic improvements are likely contributors to the crime drop.

Guns and Gun Control Policies . Finally, while explanations derived from guns and gun control policies drew a lot of attention early in the crime drop debate, mainly because such a large percentage of homicides are gun-related (Cook & Laub, 1998), interest in this explanation has diminished over time. The early interest in the relationship between violent crime and firearms made sense—the rate of violent crimes committed with firearms rose in the 1980s and 1990s and subsequently dropped. But over time, scholars have downplayed the degree to which gun control and concealed weapon laws contributed to the crime drop (Levitt, 2004). For example, some researchers found that the percentage of total killings by young males remained stable during the time of the crime drop, which was troubling since young males are much more likely to use a gun in a homicide than others, and other researchers discovered that the passage of the Brady Act gun control legislation in 1993 had no influence on homicide trends. Adding to the downfall of this explanation, researchers evaluating gun buyback programs and other gun control policies found that these programs also had little to do with reduction in gun violence. Even the highly publicized concealed weapon laws link to lower violent crime came under scrutiny (Lott & Mustard, 1997) when researchers revealed that the decline in crime actually predated the passage of many concealed weapon laws.

Since many of these explanations represent early responses to the crime drop, the research paper will now turn to more recent trends in the study of homicide. Clearly understanding homicide trends, particularly the crime drop of the 1990s, remains a critical focus. Moving beyond time series data of total homicide rates, scholars have acknowledged that since homicide trends differ across groups (Blumstein & Rosenfeld, 1998; Cook & Laub, 2002; Parker, 2008), these characteristics need to be accounted for in the crime drop debate. Current examples include Heimer and Lauritsen’s (in press) examination of trends in violence against women; LaFree, O’Brien, and Baumer’s (2006) exploration into racial patterns in arrest rates for multiple violent offenses; and Parker’s (2008) effort to account for the role of local labor markets in the study of race-specific homicide trends since the 1980s. All of these efforts acknowledge the diversity in the American population, including the differential levels of involvement in violence by the various groups, and argue that accounting for the differences across groups will advance understanding of the crime drop. To illustrate, a closer look at homicide trends is offered, involving two specific characteristics— racial groups and intimate partners.

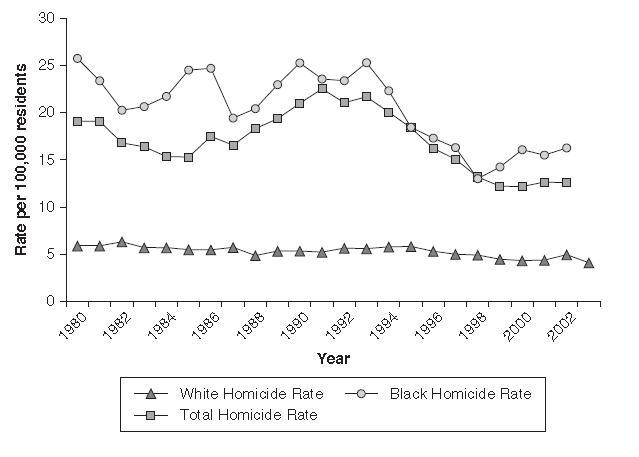

As described, the changes in total homicide rates since the 1980s were dramatic, particularly the now well-documented decline of the 1990s. But the reality is that the trends are even more striking when separated by racial groups during this time period. When homicide trends are examined for whites and blacks separately, for example, two important differences are revealed. First, the homicide victim rate among blacks is much higher, with more extreme peaks and drops than the white homicide rate or the total homicide rate (see Figure 1). In fact, the black homicide rate was 25.8 in 1980, as compared to 19.0 per 100,000 city residents for total homicide. Between 1980 and 1985, the drop in black homicide rates is similar to the rate drop in total homicides (16% versus 20%, respectively). The exception is a large dip in black homicide rates in 1987 (19.43 per 100,000 population). By the 1990s, however, the crime drop in black homicide rates was considerable in magnitude, marking a 45% drop; that is, the rate was nearly cut in half. Subsequent years, on the other hand, show an increase in black homicide rates during the 2000s (approximately ranging from 14.4 to 16.5 per 100,000).

Second, the change in white homicide rates over time is modest, to say the least, suggesting stability rather than variability when compared to black homicide rates and total homicide rates. That is, white homicide rates peaked in 1980, reaching a rate of 5.89 per 100,000 white residents, while in comparison, the total homicide rate peaked in the early 1990s. From 1980 to 1985, white homicide rates dropped 6.8% (from 5.89 to 5.49) and then dropped again in the late 1980s (a 4.5% drop), only to continue to descend throughout the 1990s and into 2000 by another 17%. This drop was far lower in magnitude when compared to total and black homicide rates. Overall, then, white homicides averaged 5 per 100,000 white residents throughout the 1980s and into the 1990s. By 1998, white homicide rates dropped below 5 per 100,000 white residents for the first time, staying in the mid to low 4s since then (Parker, 2008). Thus, among the notable differences in white homicide rates is the lack of a peak around 1991 and little to no change in offending rates throughout the 1990s. On the other hand, there were considerable shifts and fluctuations in the rates for black homicide rates and total homicide rates over the last three decades. These trends, specifically the differences across racial groups, required researchers to move the discussion away from total homicide rates. Furthermore, it drew attention to whether white and black homicide rates were converging for the first time.

Figure 1 . Homicide Rate per 100,000 Residents in Total and by Race, 1980–2003 (Adjusted Supplemental Homicide Reports)

SOURCE : Parker, K. F. (2008). Unequal Crime Decline. New York: New York University Press.

The racial patterns in homicide trends reveal some interesting findings. First, the trends in black and total homicide rates are similar over time, but white homicide rates follow a different pattern. That is, while both black and total homicide rates experienced a decline in the early 1980s, followed by increases in the late 1980s, only to drop again in the 1990s, the decline in white homicide rates was more modest and steady over the 24-year period. An equally important issue is whether the racial gap in homicide is persisting or narrowing over time. Recent evidence suggests that the racial gap has indeed narrowed, and the racial disparities between groups have declined with the crime drop. That is, by examining the racial difference in homicide offending rates (based on the ratio of black to white homicide rates), it is now known that both black and white homicide rates decreased in the late 1990s and that the racial gap between these groups also narrowed considerably (in fact, by approximately 37%). This is an important reality about homicide that only recently gained attention, largely due to the work by LaFree et al. (2006), and it cannot be understated. In LaFree et al.’s work, they reveal that the black– white gap in violence was exceptionally high during the 1960s, but that gap has decreased over time. They argue that the narrowing of the racial gap is likely linked to the narrowing of crime-generating structural characteristics, such as social and economic indicators. According to LaFree et al., only by examining homicide trends separately by racial groups is it apparent that the racial gap has narrowed. Furthermore, evidence has surfaced that the narrowing of the gap is largely attributed to the rapid decline in black homicide rates during the 1990s, more than to any changes in white homicide rates (see Parker, 2008). This finding alone adds considerable weight to the efforts to diversify the study of homicide.

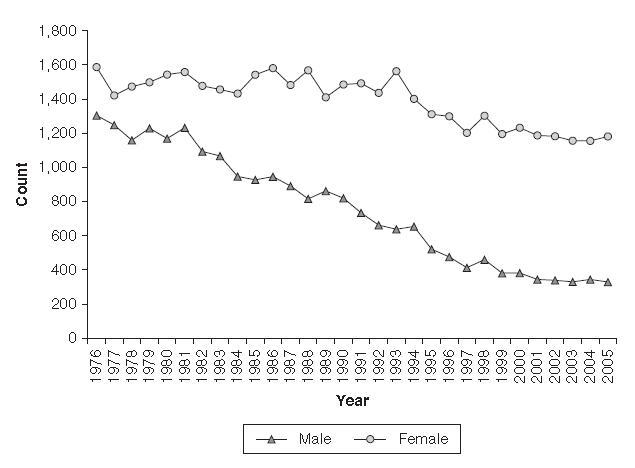

Intimate partner homicide has also gained attention in recent years, partly because of the efforts by feminist scholars to bring awareness to violence among intimate groups. While intimate partners (i.e., spouses, ex-spouses, boyfriends, and girlfriends) make up approximately 11% of all homicides, females are much more likely to be killed by an intimate partner than males. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, while both the number of male and female victims of intimate partner homicides dropped from 1976 to 2005, the number of males killed by an intimate partner had the most significant drop (75%) since 1976. On the other hand, the decline for females killed by an intimate partner was only witnessed after 1993 (see Figure 2).

As research in this area grows, descriptive accounts reveal that intimate partner homicide trends differ not only by the gender of the victim and offender, but also by the type of victim–offender relationship and the race of the victim (Browne & Williams, 1993; Gallup-Black, 2005; Puzone, Saltzman, Kresnow, Thompson, & Mercy, 2000). Essentially, while total intimate partner homicide has decreased over time, much like total homicide rates, once these rates are examined separately by gender, relationship type, or race, significant differences emerge. For instance, males have experienced a greater decline in intimate partner homicide victimization than females, and blacks more so than whites. In addition, intimate partner homicide among married persons has decreased, but homicide involving nonmarried persons has increased over time. In fact, the rise in nonmarried intimate partner victimization is most pronounced among white females. A number of reasons for the specific trends in violence among intimate partners, particularly the differences across gender and relationship type over time, have been offered. Some of these explanations are outlined here.

Figure 2 . Intimate Partner Homicides by Gender, 1976–2005

SOURCE : Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2008). Supplemental Homicide Files. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics.

The exposure reduction hypothesis proposes that factors that reduce the exposure or contact between violent intimate partners should decrease the probability of intimate partner homicide, because the opportunity for violence would be removed. A number of factors have been examined to determine the exposure reduction effects on intimate partner homicide. These factors include access to domestic violence resources, declining domesticity, and improved economic status of females.

Access to domestic violence resources, specifically the availability of legal (i.e., presence of statutes pertaining to domestic violence) and extra-legal services (i.e., number of shelters and other programs), is related to the decline in the rates of female-perpetrated intimate partner homicide, but less so for male-perpetrated intimate partner homicide (Browne & Williams, 1989; Dugan, Nagin, & Rosenfeld, 1999, 2003). On the other hand, research has also shown that some domestic violence resources (e.g., prosecutors’ willingness to prosecute) have the unintended consequence of putting women more at risk for intimate partner homicide victimization (Dugan et al., 2003). Because the role of domestic violence resources has been largely inconclusive, increasing divorce rates, declining marriage rates, an improved economic status of women, as well as other economic conditions, have received attention, partly because they consistently have been found to predict intimate partner homicide (Dugan et al., 1999, 2003; Reckdenwald, 2008; Rosenfeld, 1997).

Reflecting a decline in domesticity, rising divorce rates and the general trend toward declining marriage in the United States have surfaced as strong predictors of intimate partner homicide largely because these factors reduce the exposure to violence. For instance, divorce rates would result in fewer married couples living together and would therefore reduce the exposure of violent couples. The same idea applies to falling marriage rates, which would reduce the exposure of violent couples because fewer individuals would be getting married and living together. Rosenfeld (1997) examined intimate partner homicide trends in St. Louis, Missouri, and found that 30% of the decline in African American spousal homicides was attributable to falling marriage rates and rising divorce rates.

However, decreasing marriage rates may mean that more individuals are cohabitating without getting married. Cohabitation has been shown to be an important risk factor in intimate partner homicide. Wilson, Johnson, and Daly (1995) found that females that cohabitate with their partner are 9 times more likely to be killed by their intimate partner than are married females. Interestingly, other researchers have found that cohabitating men with female partners are 10 times more likely to be victims of intimate partner homicide compared to men in married relationships.

Improvement in the economic status of women has an exposure-reducing effect, reducing the rates of intimate partner homicide. Improvements such as higher educational attainment, income, and employment increase the opportunities available to women, and thus reduce the likelihood that they will resort to killing their male partners. Dugan et al. (1999) found that females’ improved status was associated with a reduction in intimate partner homicide victimization, particularly male intimate partner homicide victimization. That is, the increase in females’ relative income is associated with a decline in married female–perpetrated homicide. Furthermore, an increase in females’ relative educational attainment is associated with a decline in nonmarried male victimization. They suggest that “more educated women are better able, and perhaps more willing, to exit violent relationships and thus avoid killing their partner” (pp. 204–205).

While research has shown the importance of reducing the exposure between intimate partners in violent relationships, it is well-known that the highest risk for homicide is when the victim leaves the relationship, and this is especially true for females who are killed by their male partners (Block, 2000). Thus, retaliation by the abusive partner from domestic violence interventions is another important consideration. Dugan et al. (2003) found a retaliation effect where domestic violence resources actually increased homicide between intimate partners because they failed to effectively reduce exposure between intimate partners. In fact, the prosecutor’s willingness to prosecute violators of protection orders, though intended to reduce exposure between violent intimate partners, actually caused a retaliation effect where homicide increased for married and unmarried white females and African American unmarried males. They concluded that “being willing to prosecute without providing adequate protection may be harmful” (p. 192). Reckdenwald (2008) also found that the number of shelters per 100,000 females was significantly related to intimate partner homicide. Despite all the efforts to increase shelter availability to females in violent relationships, it appears that the increase in availability is actually associated with an increase in intimate partner homicide. For instance, in 1990 and 2000, the increase in the shelter rate was related to an increase in male-perpetrated intimate partner homicide. It was concluded that efforts to prevent domestic violence and homicide need to also provide adequate protection during times that are characterized by increased violence.

Aside from exposure reduction and retaliation effects, recent research has explored the link between economic deprivation and intimate partner homicide over time (Reckdenwald, 2008). The main idea is that, even though women have experienced improvements economically since the 1960s, they still lag behind their male counterparts in regard to occupational prestige and income levels. Furthermore, women are much more likely to be impoverished than males. Economic deprivation arguments allows researchers to tap the influence of poverty, unemployment, and the dependency on public assistance on the trends in male- and female-perpetrated intimate partner homicides over time, particularly since patterns of intimate partner homicide involving males and females diverge over time. Reckdenwald (2008) found that cities that had the greatest levels of change in female poverty, unemployment, and public assistance from 1990 to 2000 were also areas that experienced significant changes in female-perpetrated intimate partner homicides, suggesting that trends in such homicide were largely influenced by persisting economic deprivation among females.

As noted, overall attempts to explain the different trends in male and female intimate partner homicide have examined a number of different factors, including domestic violence resources, declining domesticity, improving economic status of females, and economic deprivation. Though a conclusive explanation has not surfaced, separating homicide trends by gender and the victim–offender relationship gives a better understanding of the nature of the crime drop in the 1990s.

The study of homicide invokes a scientific investigation of the frequency, nature, and causes of one human being killing another. As researchers explore criminal homicide, they tend to examine murder and nonnegligent manslaughter as defined by official sources (such as the UCR), which excludes justifiable homicide, manslaughter caused by negligence, suicide, or attempted murders. There are generally two national sources of homicide data—the Uniform Crime Reporting Program of the FBI and mortality files from the Vital Statistics Division of the National Center for Health Statistics. Even though these data sources are not without limitations, particularly as they relate to missing data on key characteristics of victims or offenders involved in these incidents, homicide remains the most accurately recorded and documented offense relative to other types of criminal behavior.

One of the most critical questions facing scholars and policymakers today is this: Why did homicide rates decline so considerably during the 1990s? As described here, UCR Supplemental Homicide Reports show that homicide rates fell sharply in U.S. cities in the 1990s. In fact, homicides were almost cut in half, declining approximately 46% during this 10-year period and plunging to their lowest point in 35 years. Scholars have offered a number of potential explanations, including greater police presence, prison expansion, reduced handgun availability, tapering drug (specifically crack cocaine) markets, gains in the economy, and age shifts in the population. Unfortunately, a lack of data and other measurement issues restrict definitive tests of these ideas and explanations.

Because the reasons for the crime drop remain largely unanswered, scholars have moved toward both documenting the potential differences in homicide trends across specific groups and exploring the nature of homicide trends in more detail. Two examples of recent efforts are provided: (1) the study of racial patterns in homicide trends and evidence of a convergence in black and white homicide rates over time and (2) research on how homicide among intimate partners differ by gender of the victim, type of relationship, and race, and recent attempts to explain the different trends in intimate partner homicides over time. As these examples clearly show, total homicide rates mask the nature of the crime drop, ignoring the diversity in trends and differences in life circumstances across groups based on race, gender, and other characteristics. The reality of the crime drop and an understanding of homicide trends over time require moving beyond a general investigation of total homicide rates to explore homicides among distinct groups more closely.

- How to Write a Research Paper

- Research Paper Topics

- Research Paper Examples

Bibliography:

- Block, C. R. (2000). The Chicago Women’s Health Risk Study. Risk of serious injury or death in intimate violence: A collaborative research project [Final report to the National Institute of Justice]. Retrieved August 21, 2013, from http://www.icjia.state.il.us/public/pdf/cwhrs/cwhrs.pdf

- Blumstein, A. (1995). Youth violence, guns, and the illicit-drug industry. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 86(1), 10–36.

- Blumstein, A., & Rosenfeld, R. (1998). Explaining recent trends in U.S. homicide rates. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 88, 1175–1216.

- Blumstein, A., &Wallman, J. (2001). The crime drop in America. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Browne, A., & Williams, K. R. (1989). Exploring the effect of resource availability and the likelihood of female-perpetrated homicides. Law and Society Review, 23, 75–94.

- Browne, A., & Williams, K. R. (1993). Gender, intimacy, and lethal violence. Gender & Society, 7, 78–98.

- Cook, P., & Laub, J. (1998). The unprecedented epidemic in youth violence. In M. Tonry & M. H. Moore (Eds.), Youth violence: Crime and justice (Vol. 24, pp. 27–64). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Cook, P., & Laub, J. (2002). After the epidemic: Recent trends in youth violence in the United States. In M. Tonry (Ed.), Crime and justice: A review of research: Vol. 4 (pp. 1–37). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Dugan, L., Nagin, D. S., & Rosenfeld, R. (1999). Explaining the decline in intimate partner homicide: The effects of changing domesticity, women’s status, and domestic violence resources. Homicide Studies, 3, 187–214.

- Dugan, L., Nagin, D. S., & Rosenfeld, R. (2003). Exposure reduction or retaliation? The effects of domestic violence resources on intimate-partner homicide. Law & Society Review, 37, 169–198.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2008). Supplemental homicide files. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics.

- Fox, J. A. (2004). Missing data problems in the SHR. Homicide Studies, 8, 214–254.

- Gallup-Black, A. (2005). Twenty years of rural and urban trends in family and intimate partner homicide. Homicide Studies, 9, 149–173.

- Goldstein, P. J. (1985). The drug-violence nexus:A tri-partite conceptual framework. Journal of Drug Issues, 15, 493–506.

- Heimer, K., & Lauritsen, J. L. (in press). Gender and violence in the United States: Trends in offending and victimization. In R. Rosenfeld & A. Goldberger (Eds.), Understanding crime trends. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

- LaFree, G., O’Brien, R., & Baumer, E. (2006). Is the gap between black and white arrest rates narrowing? National trends for personal contact crimes, 1960 to 2002. In R. Peterson, L. Krivo, & J. Hagan (Eds.), The many colors of crime: Inequalities of race, ethnicity, and crime in America (pp. 179–198). New York: New York University Press.

- Levitt, S. D. (2004). Understanding why crime fell in the 1990s: Four factors that explain the decline and six that do not. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 18, 163–190.

- Lott, J. R., & Mustard, D. B. (1997). Crime, deterrence, and right-to-carry concealed handguns. Journal of Legal Studies, 26, 1–68.

- Parker, K. F. (2008). Unequal crime decline: Theorizing race, urban inequality, and criminal violence. New York: New York University Press.

- Puzone, C. A., Saltzman, L. E., Kresnow, M-J., Thompson, M. P., & Mercy, J. A. (2000). National trends in intimate partner homicide. Violence Against Women, 6, 409–426.

- Reckdenwald, A. (2008). Examining trends in intimate partner homicide over time, 1990–2000. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Florida, Gainesville.

- Rosenfeld, R. (1997). Changing relationships between men and women: A note on the decline in intimate partner homicide. Homicide Studies, 1, 72–83.

- Wilson, M., Johnson, H., & Daly, M. (1995). Lethal and nonlethal violence against wives. Canadian Journal of Criminology, 37, 331–361.

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on criminal justice and get your high quality paper at affordable price.

ORDER HIGH QUALITY CUSTOM PAPER

Related Posts

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BJPsych Open

- v.6(5); 2020 Sep

Families of victims of homicide: qualitative study of their experiences with mental health inquiries

Department of Psychological Medicine, University of Auckland; and Counties Manukau District Health Board, New Zealand

Alan F. Merry

Department of Anaesthesiology, Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, University of Auckland; and Department of Anaesthesia, Auckland City Hospital, New Zealand

Ron Paterson

Faculty of Law, University of Auckland; Melbourne Law School, University of Melbourne, Australia; and New Zealand Government Inquiry into Mental Health and Addiction, New Zealand

Sally N. Merry

Department of Psychological Medicine, University of Auckland; Cure Kids Duke Family Chair in Child and Adolescent Mental Health, New Zealand; and Werry Centre for Child and Adolescent Mental Health, New Zealand

Associated Data

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2020.84.

The authors report direct access to the study data. Access to transcripts of interviews with participants is ongoing and stored in accordance with New Zealand ethics committee guidelines. The analysed data is provided and can be accessed via the supplementary data.

Investigations may be undertaken into mental healthcare related homicides to ascertain if lessons can be learned to prevent the chance of recurrence. Families of victims are variably involved in serious incident reviews. Their perspectives on the inquiry process have rarely been studied.

To explore the experiences of investigative processes from the perspectives of family members of homicide victims killed by a mental health patient to better inform the process of conducting inquiries.

The study design was informed by interpretive description methodology. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with five families whose loved one had been killed by a mental health patient and where there had been a subsequent inquiry process in New Zealand. Data were analysed using an inductive approach.

Families in this study felt excluded, marginalised and disempowered by mental health inquires. The data highlight these families’ perspectives, particularly on the importance of a clear process of inquiry, and of actions by healthcare providers that indicate restorative intent.

Conclusions

Families in this study were united in reporting that they felt excluded from mental health inquiries. We suggest that the inclusion of families’ perspectives should be a key consideration in the conduct of mental health inquiries. There may be benefit from inquiries that communicate a clear process of investigation that reflects restorative intent, acknowledges victims, provides appropriate apologies and gives families opportunities to contribute.

Families who have experienced the loss of a loved one as a consequence of homicide where the perpetrator was receiving mental healthcare are a unique group whose voices have rarely been sought. 1 A homicide by a person in receipt of mental healthcare is a serious incident 2 and investigations of mental healthcare related homicides may give families an opportunity to present the victims’ perspective. 3 Key principles for investigating serious incidents in healthcare include a process that is open and transparent and an approach that is objective, timely and systems focused. 2 The purposes of inquiries may be to establish facts, provide an impetus to learn from events leading to the incident, 4 hold multiple people or systems to account or to reassure the public. 5

Staff, patients, victims and perpetrators and their families and carers are all affected by homicide. An inquiry provides a means to highlight gaps in systems and processes of care that can result in serious incidents. 6 Serious incidents include acts or omissions in care that can result in serious injury or unexpected death. 2 Homicide, the crime of killing a person, is subject to particular scrutiny when the perpetrator had a psychiatric illness as the care of the perpetrator may be retrospectively analysed to determine whether the death could have been prevented. 7 It is recommended that patients and victims’ families are involved and supported throughout an investigation process. 2 However, victims of mentally disordered offenders feel isolated and unsupported by healthcare and legal systems. 1 , 8

Types of inquires in New Zealand

In New Zealand, inquiries following mental healthcare related homicide include hospital serious incident reviews (internal and external), coronial inquests and formal complaint procedures. District health boards, responsible for providing mental health services in New Zealand, may conduct a serious incident review. These usually precede coronial inquiries or external inquiries requested by the Director of Mental Health (within the Ministry of Health, the government agency responsible for district health boards) under specific mental health legislation and investigations initiated by a formal complaint to the New Zealand Health and Disability Commissioner.

Information may be shared between different inquiries to avoid duplication and expedite investigations (according to a Memorandum of Understanding between the Office of the Chief Coroner and the Office of the Health and Disability Commissioner, 2016). Unlike the National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness, 9 New Zealand does not hold details of homicides and suicides by people under the care of mental health services in a central repository for clinicians to access, for conducting research or for developing national policies. There is no official guidance to standardise inquiries across the 20 district health boards in New Zealand. 10

Families of victims of mental healthcare related homicide seek an explanation of what happened and wish to know what improvements will be made to services. 11 , 12 Yet such families describe invalidating experiences, 13 difficulties establishing contact with hospital managers and struggles with obtaining information from mental health providers about investigations of perpetrators’ care. 8 Healthcare services may not feel the same obligation to disclose information to victims’ families 8 compared with families whose loved one died as a result of a medical adverse event 14 and may be uncertain about what information to share with families. 15

Theoretical approaches to inquiries have been proposed for adverse events in healthcare. 16 , 17 Reason's model, used to analyse complex industrial accidents, 18 has been adapted for use in medical contexts. 16 This conceptual framework includes consideration of attributes of the patient, team and organisation in relation to the outcome. Mental health inquiry panels have developed systems-based protocols to conduct inquiries, a form of structured analysis that explores contributory technological, psychological, social and human factors to adverse outcomes. 17 There is limited evidence that investigations with a systems focus are effective in recommending and implementing useful changes to mental health services. 16

Our observation that the views of families were often missing in inquiries led to this study. Inquiries have reported on relationships between healthcare and other systems and how peoples’ actions and choices are influenced by the system within which they are working. 19 , 20 The authors’ experiences of working within New Zealand's healthcare system influenced the study design. Our intent was to return findings to the field of practice and present evidence for consideration of potential changes to inquiries that could benefit those involved with them.

In this study we have explored families’ experiences of inquiries related to mental healthcare. Victims of crime who encounter the legal system have a high risk of a negative mental health impact and of re-traumatisation. 21 There are few studies that specifically document families of victims’ experiences of investigations into the mental healthcare of perpetrators. 21 , 22 In principle, including the perspectives of families of patients and victims is good practice for inquiry panels. Yet, families of victims of homicide describe difficulty navigating mental health systems and obtaining information when perpetrators have a psychiatric illness. 8

This study is part of a larger body of work to investigate the perspectives of various stakeholders in mental healthcare related inquiries in New Zealand, including their expectations of and experiences with the process. Our wider study extends to the views of clinicians, and members of inquiry panels. This article reports on the participation of families of victims in mental healthcare related inquiries, their understanding of an inquiry's purpose, and the support they received. By investigating families’ experiences with mental healthcare related inquiries following a homicide perpetrated by a patient, there is potential to identify how mental health services can better respond to their needs and concerns when conducting reviews of serious incidents.

Study design and methodological considerations

The study design was informed by interpretive description, 23 – 25 an approach to qualitative research whereby ‘logic derived from the disciplinary orientation’ 25 is applied to analysing a phenomenon. Our research explored families of victims’ experiences of serious incident reviews following mental healthcare related homicide. Our experiences as clinicians, researchers and government policy advisors span systems of general and forensic psychiatry, anaesthesia, law and the safety and quality of healthcare. The primary analysis was conducted by L.N., who is a forensic psychiatrist. Interpretive description was chosen to address the study's question as it enables clinicians to engage with research at the junction of clinical practice. The focus of our research question was the participants’ experiences of district health board inquiries. We presumed that our research question intersected with clinical practice and policy, and that the first author's (L.N.) clinical experience in mental health and forensic services, and with conducting inquiries, would enhance the qualitative analysis undertaken. The process was iterative with immersion and deep engagement with the data (by L.N.) to develop initial codes and facilitate the development of conceptual themes, sharing the analysis with participants for further feedback, and discussing findings with mental health clinicians to broaden perspectives. 26 To enhance trustworthiness, an independent researcher (a psychologist experienced in qualitative methods) co-coded the data, provided a commentary and contributed to the development of themes over a period of 6 months. This was developed further by disseminating findings to clinicians working in mental health services. In this step, L.N. presented initial findings to clinicians and discussed how these might be received and applied in practice.

Participants

Participants were families of victims of mental health homicide, that is, a member of their families had been killed by a patient under the care of mental health services in New Zealand. A family may be defined as a group of people that may be made up of partners, children, parents, aunts, uncles, cousins and grandparents. The term ‘under the care of mental health services’ refers to patients formally under the care of a district health board mental health team (secondary services). Additional inclusion criteria were: age 18 years or above; able to give informed written consent; a serious incident review was conducted by a district health board mental health service between 2002 and 2017; and contact with the family did not breach New Zealand privacy legislation. A New Zealand Health and Disability Ethics Committee approved the study, with conditions that participants be recruited via a third party (ethics approval number 17/NTA/228).

Originally, we proposed a purposive sample to access participants and approached two key New Zealand agencies: Victim Support (a non-governmental organisation that supports victims of crime) and the Ministry of Justice (which holds the Victim Notification Register containing details of victims, for the purpose of informing victims about events regarding the offender). Both agencies declined to facilitate entry into the study; the former cited a lack of resources and the latter cited privacy interests. Accordingly, the study used a snowball sample. In total, five participant families were recruited between August 2018 and March 2019. The first participants were recruited via a key informant in mental health advocacy, who recommended a chain of potential respondents. Additional participants were recruited through hospital managers and family advisors based at the district health board mental health services in Auckland, New Zealand, who identified family members of people who had been victims of homicide perpetrated by a mental health patient. Participants who expressed interest in the study were sent an information sheet and a copy of the interview schedule, which was followed up by a telephone call from the first author. Participants gave their written consent to take part in the study.

Before commencing the study, the semi-structured interview schedule (see Appendix) was checked by, discussed with, and approved by a family member of a patient who had died under the care of hospital services (not mental healthcare related). Between July 2018 and March 2019, the first author interviewed all participants. They were invited to bring a support person and asked if they wanted specific cultural support. Interviews began with acknowledging the victim and exploring families’ involvement and understanding of inquiries. Families were also asked to reflect on their experiences of the inquiry process, including the support they received. Interviews were guided by participants’ concerns and adjusted accordingly. Some participants provided written reflections. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Following the interviews, participants were offered psychological counselling, funded by the study.

The interview transcripts were returned to the participants to confirm accuracy of the data. Names and locations in the transcripts were de-identified and a code was assigned to each transcript. NVivo was used to store and manage the data. All transcripts were read intensively and primarily coded by the first author, using an inductive approach. 27 , 28 Memos, observations, reflections and critical questions were recorded across the data-set. An independent researcher (a psychologist-researcher) co-coded a portion (20%) of the data, peers reviewed the coding process and verified the coding framework.

During the analytic process, codes and memos were checked against the transcripts. As described above, concept themes were developed. 29 , 30 The results were presented to mental health clinicians at educational forums in New Zealand and Australia. Verbal and written feedback was incorporated into the development of key themes. The themes were further developed in discussion with an external supervisor (a psychiatrist) of the study. This step may be described as the ‘thoughtful clinician test’, 25 whereby expert practitioners are considered a ‘collateral data source’ to critically reflect on perspectives of the phenomena. This formal relationship also acknowledged the sensitive and emotionally demanding nature of the research. 31

Five families of homicide victims participated in separate interviews and one family provided additional written reflections. There were a total of nine participants in the study involved with four different New Zealand district health boards that included family members who were parents, siblings, sons and daughters of the victims ( Table 1 ). One family included parents of a mental health patient who was killed by another patient. The remaining family members had little or no experience of mental health services as consumers. The families were involved in a range of inquiries, including hospital serious incident reviews (internal and external), coronial inquests and formal complaint procedures. All participants accepted post-interview counselling sessions. Three elements of a good inquiry emerged from the data: understanding the perspectives of families of victims, communicating a clear process of inquiry, and acting with restorative intent. Quotations illustrating these themes are presented (see also the supplementary data, available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2020.84 ).

Description of participants

Understanding the perspectives of families of victims

The families in the study expressed initial bewilderment that their loved one had been killed by a mental health patient and disbelief when they felt contact with hospital authorities lacked empathy for their loss and circumstances. Their experiences of mental health inquiries into the care of the perpetrator were marked by exclusion, marginalisation and disempowerment. Several participants spoke of their disappointment that the victim and their needs were not enquired into.

‘[Victim] wasn't at the forefront of his own death. In a way he was collateral damage, he was secondary to their thoughts. They were more worried about their reputation and what they did, or didn't do, what was missed out was health and well-being and recovery. They weren't concerned about ours, or how he died.’ (Family 1)

These participants’ concerns continued as they described their sense of exclusion from the inquiry process. These families felt angry at being ‘shut out’ and some described their perception of a lack of respect shown to them by hospital providers. This was more prominent when participants discovered information second-hand, from the media.

‘The way I found out was pretty much newspaper articles, yeah literally. So all my information was newspaper articles and I didn't find that acceptable.’ (Family 2)

The sense of exclusion was compounded by feeling marginalised from the inquiry process. Some families met with hospital representatives and spoke about their concerns that district health boards focused on being defensive, rather than empathetic. These participants expected an acknowledgement of loss of their family member. With the exception of one family, condolences were absent.

‘I was expecting them to say “look we're really sorry about that” or “this has happened to [victim]”. I was numb at that stage, I just walked out. My cousin was behind me and I did hear him say “I can't believe you people just sat there and didn't say sorry”. Then we just left and that was all there was to it.’ (Family 3)

The participants’ attempts to access information from hospital authorities were frequently unsuccessful. They were told the information could not be divulged because of the need to protect the perpetrators’ privacy. Several families requested basic details relating to the perpetrator, or inquiry. They emphasised that they wanted information about public safety, not confidential medical information. Over time, these family members continued to have unanswered questions about the perpetrator's mental healthcare.

‘It [an inquiry] could have given me some closure instead of having all these questions and no one to answer them. There are always so many questions. There was just no one to answer or give me an insight of why it happened and how it happened.’ (Family 2)

These families described their disempowerment and the cumulative psychological stress that arose from their attempts to obtain information.

‘People are absolutely appalled at the way [we've] been treated and the length of time it's gone on. The emotional trauma that it has caused us. It's been absolutely horrendous.’ (Family 4)

The participants in the study spoke of difficult emotions in waiting for various inquiry processes to be completed over a period of months and, in some cases, years. Some described the double pain of loss and injustice as perpetrators were found legally insane. In these cases, families highlighted they felt further excluded and isolated, with few avenues of recourse to address their concerns about process.

Communicating a clear process of inquiry

All the families in the study referred to a serious void in communication from mental health services. These families described a paucity of information about the inquiry process and its purpose. One family articulated their response to the lack of process:

‘There was no process, that's what's most frustrating, that's why I feel like I just want to sue [the hospital]. Hurt them in some way so that it makes them have a process. I just try to forget about it, I just bury it deep and don't talk about it or think about it, I don't ever.’ (Family 3)

These participants considered essential elements in communicating process to include an open invitation to participate; a verbal and written explanation about the purpose of the inquiry and how the case would be investigated; and sharing the findings and recommendations with them. Several highlighted that written information may have helped them understand what the process of a district health board inquiry entailed:

‘I don't know whether it was because we were caught up in the court case or whether it was too fresh. We didn't really understand what the review process was, who would be part of it, what our involvement would be for opportunity for input.’ (Family 5)

Several families reported that their contact with district health boards during and following inquiries was harmful. Some examples were given: a brief summary report in their mailbox; being made aware of an inquiry after it had been completed; and not receiving findings or feedback following the conclusion of an inquiry. They spoke of lost opportunities to make sense of events in the narrative of the victim, identify gaps in mental health service care of the perpetrator and contribute to improving services.

‘If [we] could have been told about those results and the processes that they put in place to actually learn from what happened, I believe that would have made a difference, it might not have resolved all the anger or frustrations but it would have been a big step in the healing.’ (Family 3)

Several families expressed their feelings of frustration and mistrust of hospital providers over time. They viewed access to support and advocacy, as important in understanding their rights, and what they could expect from mental health services. As they progressed with other independent coronial or complaint-related reviews, they became concerned about transparency in the conduct of mental health inquiries.

'Transparency is a tough one to achieve when [the medical profession] is self-regulating and does its own review. There needs to be an independent review and you can't rely on the [hospital] to do its own review because it just doesn't work. You're not going to get people crucifying themselves for their own performance.’ (Family 3)

Despite their concerns, the participants described a role for mental health inquiries in answering specific questions about the perpetrators’ care. This was something often addressed less effectively in legal inquiry processes. Their experiences of coronial inquests were mixed as in some cases a coroner's review occurred many years after the homicide. In general, the participants spoke more positively about coronial inquiries. Several participants described the difficulty in understanding processes and the links between different inquiries and proceedings after they had been completed.

‘With the benefit of hindsight, I would have considered taking legal advice to better understand options for recourse… the process used to incarcerate [perpetrator] under the Mental Health Act, the process of review of [perpetrator]'s imprisonment and/or release…and civil proceedings against [perpetrator] or the [hospital] for the emotional harm they have caused us.’ (Family 3)

Several families in the study stated that the provision of clear information at the outset may have helped them understand what they could expect from an investigation.

‘[Victim] died and then that was it. If we'd got something back from the report, we would have got some sense of closure.’ (Family 5)

These participants were left with unanswered questions related to the perpetrators’ care and recommendations and changes that would be made to services as a result of an inquiry.

Acting with restorative intent

The participants in this study spoke of their grief in losing their family member and described actions that could promote healing. Actions that demonstrated restorative intent emerged as an important attribute of the inquiry process: for district health boards to demonstrate a sincere intent to engage with them; to acknowledge the victim, apologise to the family and convey a commitment to undertake an inquiry with integrity. For several participants, the lack of acknowledgement of their loss and needs perpetuated their grief:

‘No one wants to acknowledge that you had a stake in the whole thing, an opinion, maybe a solution or a point of view.’ (Family 1) ‘One thing that would have really helped was an acknowledgement and some form of apology [from mental health services]. We've never had that…just recognising a life was lost and that person was here. They need to realise it's people they are dealing with.’ (Family 4)

For one participant, the humanity of the victim was not acknowledged until many years later at a coronial inquest:

‘It [coronial inquest] was the first time that [victim] had ever been thought of as a person.’ (Family 4)

Several families wanted to contribute to district health board inquiries to enable mental health services to improve care, and for their perspectives to be recognised and valued.

‘I do see something coming out of the process if I was involved as long as I had an opportunity, not a right. An opportunity to query, or challenge or respond, not just get the findings…prior to that just saying, these are our preliminary findings, we value your input, it could be valuable to us. At least it would give you a sense that you are actually contributing to the process getting better.’ (Family 3)

These families wanted to see evidence that meaningful learning had taken place to help prevent similar mistakes in the future.

‘I think confirmation a lesson has been learnt. If you had feedback from an inquiry to say we've learnt this lesson, we've amended our process. Thank you for your input. That would make me feel okay, something good has come from this.’ (Family 3)

Several participants related concerns that inquiries were not disseminated to mental health services nationally and that district health boards did not learn from inquiries as inquiry recommendations were not formally enforced.

‘All they are is recommendations, this is a real “stuff you” to the victims, not only did [the hospital] ignore them, they also sent a letter to the coroner telling him he was wrong…That just piles contempt on top of contempt.’ (Family 3) ‘It's all very well putting something on a piece of paper…unless you actually act and implement change, then to be honest the review's a total waste of time.’ (Family 4)

Several participants spoke of feeling aggrieved and re-traumatised by denial of accountability by mental health services. One family received a mandated apology many months later following an inquiry. These actions were perceived by participants as harmful, insincere and disrespectful to the memory of their loved one.

‘We've had to fight for everything. When I say fight I mean Official Information Act, Ombudsman, everything, they would not give us anything without making us fight for it. That's going on behind the scenes while you're trying to go through a court process into a murder. You're not only fighting the justice system, you're fighting the Ministry of Health, and individual [hospital service] for stuff that should be available pretty early, as of right.’ (Family 1)

Several participants who had negative encounters with mental health services proactively sought further information from mental health services and accountability from governmental bodies. Some escalated their concerns to formal complaint procedures and became advocates for families with similar circumstances.

In this exploratory study, we examined the experiences of mental health inquiries from the perspective of a small number of families of victims of homicide in New Zealand. Their complex experiences suggest a strong sense of exclusion and disempowerment following the death of their family member. We were moved by the depth of feeling of these participants over time and their unresolved questions despite the inquiry processes. Our results suggest that these families sought to engage with district health boards during these inquiries specifically to better understand the circumstances of their family member's death and what changes could be made to secondary mental health services to prevent a similar death in the future. They received limited information and little or no formal support from mental health services. First steps in promoting healing would presumably include an acknowledgement of loss by district health boards and the communication of a clear process but these steps were typically missed out. 1 , 32

Although this study has been carried out in a small population in New Zealand, there are similar processes for inquiries internationally. 33 The UK's National Health Service Serious Incident Framework notes a central premise of an investigation is to ensure learning is prioritised to prevent the likelihood of similar incidents occurring in the future. 2 A review of investigations of the deaths of patients concluded that many carers and families do not experience healthcare providers as open and transparent. 8 Secondary victims, such as families of victims of mentally disordered offenders, who may have encounters with legal systems in these processes may be exposed to psychological risks. 13 Many do not have access to an advocate and feel unsupported. 8 The present study contributes to an ongoing dialogue about the responsibility for creating a safe psychological climate for families of victims involved with mental health inquiries.

In practice, investigations vary, as does the communication of findings to families. 34 The participants in this study were involved with various medico-legal proceedings in the time that had elapsed since their family member was killed. The lengthy time frames meant it was not possible to narrow the focus of the study to one type of inquiry, for example, the hospital serious incident review of mental healthcare of the perpetrators. The study reveals the difficult experiences of families of victims in navigating multiple processes of inquiry. Not all were involved with the hospital serious incident review process. However, they emphasised this investigation as particularly important as a source of information about the events leading up to the death of their family member and the mental healthcare the perpetrator received.

This study highlights the potential for inquiries to have a restorative function, 14 , 15 in addition to that of documenting and interpreting events. 5 , 16 This is exemplified by the participants’ experiences of exclusion from inquiries that led some to pursue information and accountability through a wider system, including formal complaint and legal processes.

It is also reasonable for the family of a victim to expect an explanation, acknowledgement of 35 and apologies for any failings in care and communication in a timely and sensitive manner. 1 , 36 , 37 This study has highlighted the potential neglect of families during inquiry processes in New Zealand. We postulate that this is likely to be true elsewhere, as well. We suggest that healthcare and mental health service providers should consider families of victims as key stakeholders, obtain their perspectives and consider making formal access to support available to them. The focus on experiences of families of homicide victims as a group with distinct needs 8 could assist with debriefing and educating front-line clinicians. Our findings may encourage members of inquiry panels to view the inclusion of families of victims as a vital step in the process and one which may attenuate these families’ emotional distress. 21 Communicating a clear process and the findings of the inquiry may help a little to mitigate negative consequences of loss as a consequence of homicide. 1

Strengths and limitations

The rapport built with participants in initial contact and sensitive interviews and the capture of depth and richness of their experiences are strengths of this study. Transferability of the findings to other contexts, may be limited by the small sample size, the methodology and analytic process. These data represent the experiences of New Zealand families who chose to participate in this study but cannot be assumed to represent those of all families of victims. The participants in this study may have felt most strongly about their experience of inquiries, or found the process particularly distressing. The findings may guide reflection on approaches to deriving wider purposes and meanings from inquiries of this type. The dissemination of findings to clinicians working in mental health services revealed practical tensions in responding to families of victims at an individual level and developing policy responses to families of victims at local service and wider system levels. Although clinicians identified with the participants’ experiences, their capacity to effect changes in inquiry practice is limited to their individual contexts and involvement in inquiries.

Future research

Family members of victims of homicide are one stakeholder group in mental healthcare related inquiries, and those who participated were a small subgroup of the whole, limited to New Zealand. However, their feedback was common to all, and in line with concerns raised in the literature. Investigating whether these findings apply more generally is important. Another important group to consider is the family members of patients who have been perpetrators of homicide. Families of victims and perpetrators are both groups that are difficult to access, as their private information is held by gatekeepers. Understanding the impact of inquiries on clinicians 38 , 39 and the perspectives of those conducting inquiries would also help guide the development of a more tailored framework for conducting inquiries into serious mental health incidents, and one that can better address the needs of families. 16 , 40

Implications

The data in this study have highlighted a gap in the way inquiries are conducted. Families in this study were united in reporting that they felt excluded from mental health inquiries. We suggest that perspectives of families of mental health related homicide should be a key consideration in the conduct of mental health inquiries. There may be benefit from inquiries that communicate a clear process of investigation that reflects restorative intent, acknowledges victims, provides appropriate apologies and gives families opportunities to contribute.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the victims of mental-health-related homicide and thank their families for contributing to the study. Thank you to Peter Adams, Stephen Buetow and Janie Sheridan for their advice on qualitative methods and valuable comments on the manuscript. Thank you also to Ruth Allen for her assistance with the analysis and to Heather Gunter for her support in designing the interview schedule.

Participant interview schedule

Author contributions.

L.N. was responsible for the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. All authors contributed to the concept of the work, critically revising the content of the article and approving the final version. The authors are jointly responsible for the accuracy and integrity of the work.

This research was supported by a Faculty Research Development Fund award from The University of Auckland (L.N., grant number 3715260).

Supplementary material

Data availability, declaration of interest.

The first author reports a grant from The University of Auckland during the conduct of the study. The other authors have nothing to disclose.

ICMJE forms are in the supplementary material, available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2020.84 .

Criminal Justice Research: Homicide Essay

Criminology is the study that investigates criminal behaviors concerning an individual and a society. It covers the cause, control and nature of the behavior. It is a field related to all disciplines. As a study, criminology investigates relations among human beings and their activities in the world. Criminology has several research areas. As a study, it explores the causes, magnitudes and incidence of crime. It also gains capacity with the regulations and reaction of crime from the society and the government. Criminology depends on quantitative techniques to explore the circulation and origins of crime. Quantitative methods are systematic and practical research procedures of social phenomena via different techniques. In criminology, quantitative methods have provided the key research methods for reviewing the causes and distribution of crime. They offer numerous ways to attain data that is beneficial to a given society. In the investigation, quantitative methods involve key research forms. The forms of research include evaluation, survey and field research. This research assists criminologists in the process of finding effective and dependable data. The data obtained is sampled and then used to make key declarations about the matter being investigated. There are currently several types of data used to measure crime (Maddan, 2010).

Crime is the violation of laws that forbids it and permit punishment for its commission. In general, there are four methods to measure crime to get quantitative data. One of the methods is observation. Observation as a method is not the best way to obtain information since it does not give a reliable measure of the crime. The second method is surveys of offenders. A survey of offenders is a convenient method to measure data. The advantage of this method is that information not yet reported to authorities can be obtained. Another advantage is that crimes not recorded or reported to authorities can be discovered. Assessment of offenders avails data about them along with their victims. A Survey of offenders exposes the extent of crime perpetrated by an offender. They are helpful, particularly for victimless crimes. The third method is victimization reports. Victimization reports are established on police measures of crime. They are mainly centered on reported crimes. In normal circumstances, knowing the depth of crime is a tough task. Therefore, the various methods are combined to obtain effective data (Hagan, 2008).