Science Essay

Learn How to Write an A+ Science Essay

11 min read

People also read

150+ Engaging Science Essay Topics To Hook Your Readers

8 Impressive Science Essay Examples for Students

Science Fiction Essay: Examples & Easy Steps Guide

Essay About Science and Technology| Tips & Examples

Essay About Science in Everyday Life - Samples & Writing Tips

Check Out 5 Impressive Essay About Science Fair Examples

Did you ever imagine that essay writing was just for students in the Humanities? Well, think again!

For science students, tackling a science essay might seem challenging, as it not only demands a deep understanding of the subject but also strong writing skills.

However, fret not because we've got your back!

With the right steps and tips, you can write an engaging and informative science essay easily!

This blog will take you through all the important steps of writing a science essay, from choosing a topic to presenting the final work.

So, let's get into it!

- 1. What Is a Science Essay?

- 2. How To Write a Science Essay?

- 3. How to Structure a Science Essay?

- 4. Science Essay Examples

- 5. How to Choose the Right Science Essay Topic

- 6. Science Essay Topics

- 7. Science Essay Writing Tips

What Is a Science Essay?

A science essay is an academic paper focusing on a scientific topic from physics, chemistry, biology, or any other scientific field.

Science essays are mostly expository. That is, they require you to explain your chosen topic in detail. However, they can also be descriptive and exploratory.

A descriptive science essay aims to describe a certain scientific phenomenon according to established knowledge.

On the other hand, the exploratory science essay requires you to go beyond the current theories and explore new interpretations.

So before you set out to write your essay, always check out the instructions given by your instructor. Whether a science essay is expository or exploratory must be clear from the start. Or, if you face any difficulty, you can take help from a science essay writer as well.

Moreover, check out this video to understand scientific writing in detail.

Now that you know what it is, let's look at the steps you need to take to write a science essay.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That's our Job!

How To Write a Science Essay?

Writing a science essay is not as complex as it may seem. All you need to do is follow the right steps to create an impressive piece of work that meets the assigned criteria.

Here's what you need to do:

Choose Your Topic

A good topic forms the foundation for an engaging and well-written essay. Therefore, you should ensure that you pick something interesting or relevant to your field of study.

To choose a good topic, you can brainstorm ideas relating to the subject matter. You may also find inspiration from other science essays or articles about the same topic.

Conduct Research

Once you have chosen your topic, start researching it thoroughly to develop a strong argument or discussion in your essay.

Make sure you use reliable sources and cite them properly . You should also make notes while conducting your research so that you can reference them easily when writing the essay. Or, you can get expert assistance from an essay writing service to manage your citations.

Create an Outline

A good essay outline helps to organize the ideas in your paper. It serves as a guide throughout the writing process and ensures you don’t miss out on important points.

An outline makes it easier to write a well-structured paper that flows logically. It should be detailed enough to guide you through the entire writing process.

However, your outline should be flexible, and it's sometimes better to change it along the way to improve your structure.

Start Writing

Once you have a good outline, start writing the essay by following your plan.

The first step in writing any essay is to draft it. This means putting your thoughts down on paper in a rough form without worrying about grammar or spelling mistakes.

So begin your essay by introducing the topic, then carefully explain it using evidence and examples to support your argument.

Don't worry if your first draft isn't perfect - it's just the starting point!

Proofread & Edit

After finishing your first draft, take time to proofread and edit it for grammar and spelling mistakes.

Proofreading is the process of checking for grammatical mistakes. It should be done after you have finished writing your essay.

Editing, on the other hand, involves reviewing the structure and organization of your essay and its content. It should be done before you submit your final work.

Both proofreading and editing are essential for producing a high-quality essay. Make sure to give yourself enough time to do them properly!

After revising the essay, you should format it according to the guidelines given by your instructor. This could involve using a specific font size, page margins, or citation style.

Most science essays are written in Times New Roman font with 12-point size and double spacing. The margins should be 1 inch on all sides, and the text should be justified.

In addition, you must cite your sources properly using a recognized citation style such as APA , Chicago , or Harvard . Make sure to follow the guidelines closely so that your essay looks professional.

Following these steps will help you create an informative and well-structured science essay that meets the given criteria.

Tough Essay Due? Hire Tough Writers!

How to Structure a Science Essay?

A basic science essay structure includes an introduction, body, and conclusion.

Let's look at each of these briefly.

- Introduction

Your essay introduction should introduce your topic and provide a brief overview of what you will discuss in the essay. It should also state your thesis or main argument.

For instance, a thesis statement for a science essay could be,

"The human body is capable of incredible feats, as evidenced by the many athletes who have competed in the Olympic games."

The body of your essay will contain the bulk of your argument or discussion. It should be divided into paragraphs, each discussing a different point.

For instance, imagine you were writing about sports and the human body.

Your first paragraph can discuss the physical capabilities of the human body.

The second paragraph may be about the physical benefits of competing in sports.

Similarly, in the third paragraph, you can present one or two case studies of specific athletes to support your point.

Once you have explained all your points in the body, it’s time to conclude the essay.

Your essay conclusion should summarize the main points of your essay and leave the reader with a sense of closure.

In the conclusion, you reiterate your thesis and sum up your arguments. You can also suggest implications or potential applications of the ideas discussed in the essay.

By following this structure, you will create a well-organized essay.

Check out a few example essays to see this structure in practice.

Science Essay Examples

A great way to get inspired when writing a science essay is to look at other examples of successful essays written by others.

Here are some examples that will give you an idea of how to write your essay.

Science Essay About Genetics - Science Essay Example

Environmental Science Essay Example | PDF Sample

The Science of Nanotechnology

Science, Non-Science, and Pseudo-Science

The Science Of Science Education

Science in our Daily Lives

Short Science Essay Example

Let’s take a look at a short science essay:

Want to read more essay examples? Here, you can find more science essay examples to learn from.

How to Choose the Right Science Essay Topic

Choosing the right science essay topic is a critical first step in crafting a compelling and engaging essay. Here's a concise guide on how to make this decision wisely:

- Consider Your Interests: Start by reflecting on your personal interests within the realm of science. Selecting a topic that genuinely fascinates you will make the research and writing process more enjoyable and motivated.

- Relevance to the Course: Ensure that your chosen topic aligns with your course or assignment requirements. Read the assignment guidelines carefully to understand the scope and focus expected by your instructor.

- Current Trends and Issues: Stay updated with the latest scientific developments and trends. Opting for a topic that addresses contemporary issues not only makes your essay relevant but also demonstrates your awareness of current events in the field.

- Narrow Down the Scope: Science is vast, so narrow your topic to a manageable scope. Instead of a broad subject like "Climate Change," consider a more specific angle like "The Impact of Melting Arctic Ice on Global Sea Levels."

- Available Resources: Ensure that there are sufficient credible sources and research materials available for your chosen topic. A lack of resources can hinder your research efforts.

- Discuss with Your Instructor: If you're uncertain about your topic choice, don't hesitate to consult your instructor or professor. They can provide valuable guidance and may even suggest specific topics based on your academic goals.

Science Essay Topics

Choosing an appropriate topic for a science essay is one of the first steps in writing a successful paper.

Here are a few science essay topics to get you started:

- How space exploration affects our daily lives?

- How has technology changed our understanding of medicine?

- Are there ethical considerations to consider when conducting scientific research?

- How does climate change affect the biodiversity of different parts of the world?

- How can artificial intelligence be used in medicine?

- What impact have vaccines had on global health?

- What is the future of renewable energy?

- How do we ensure that genetically modified organisms are safe for humans and the environment?

- The influence of social media on human behavior: A social science perspective

- What are the potential risks and benefits of stem cell therapy?

Important science topics can cover anything from space exploration to chemistry and biology. So you can choose any topic according to your interests!

Need more topics? We have gathered 100+ science essay topics to help you find a great topic!

Continue reading to find some tips to help you write a successful science essay.

Science Essay Writing Tips

Once you have chosen a topic and looked at examples, it's time to start writing the science essay.

Here are some key tips for a successful essay:

- Research thoroughly

Make sure you do extensive research before you begin writing your paper. This will ensure that the facts and figures you include are accurate and supported by reliable sources.

- Use clear language

Avoid using jargon or overly technical language when writing your essay. Plain language is easier to understand and more engaging for readers.

- Referencing

Always provide references for any information you include in your essay. This will demonstrate that you acknowledge other people's work and show that the evidence you use is credible.

Make sure to follow the basic structure of an essay and organize your thoughts into clear sections. This will improve the flow and make your essay easier to read.

- Ask someone to proofread

It’s also a good idea to get someone else to proofread your work as they may spot mistakes that you have missed.

These few tips will help ensure that your science essay is well-written and informative!

You've learned the steps to writing a successful science essay and looked at some examples and topics to get you started.

Make sure you thoroughly research, use clear language, structure your thoughts, and proofread your essay. With these tips, you’re sure to write a great science essay!

Do you still need expert help writing a science essay? Our science essay writing service is here to help. With our team of professional writers, you can rest assured that your essay will be written to the highest standards.

Contact our online writing service now to get started!

Also, do not forget to try our essay typer tool for quick and cost-free aid with your essays!

Write Essay Within 60 Seconds!

Betty is a freelance writer and researcher. She has a Masters in literature and enjoys providing writing services to her clients. Betty is an avid reader and loves learning new things. She has provided writing services to clients from all academic levels and related academic fields.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

- Communicating in STEM Disciplines

- Features of Academic STEM Writing

- STEM Writing Tips

- Academic Integrity in STEM

- Strategies for Writing

- Science Writing Videos – YouTube Channel

- Educator Resources

- Lesson Plans, Activities and Assignments

- Strategies for Teaching Writing

- Grading Techniques

Science Essay Writing (First-Year Undergraduates)

Writing an Argumentative Science Essay

These resources have been designed to help teach students how to write a well-structured argumentative science essay (approximately 1,250 words) over the course of a term. They will take part in four interactive in-class activity sessions (intended to last 50 – 60 min each) that each focus on a different, critical theme in writing essays, and which are designed to supplement pre-class homework readings and short activities.

Student essays can be written to address any brief. An example is:

Identify a current controversy in science that interests you. State your opinion, and present the evidence that justifies your position.

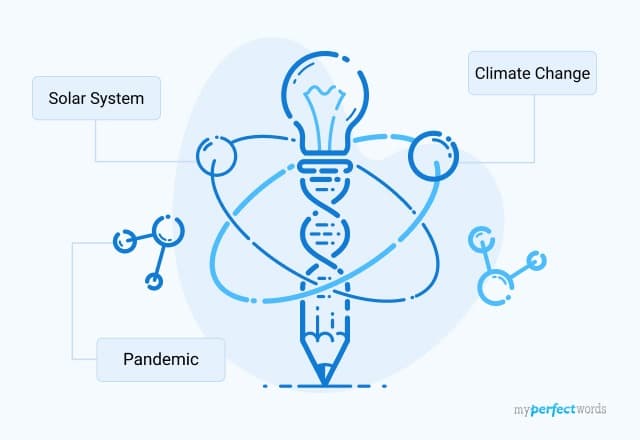

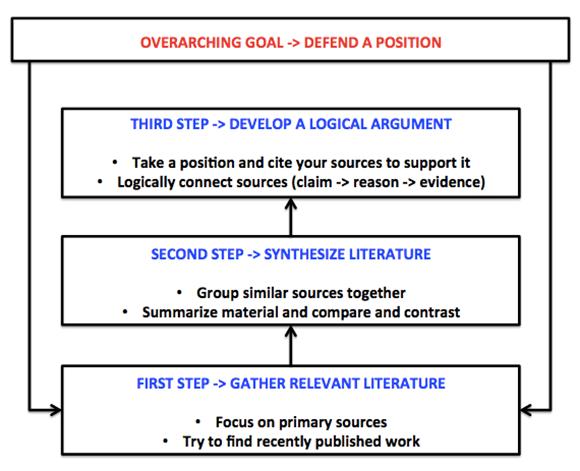

The four in-class activity sessions will help students develop their essays (see Table 1).

Table 1: The four topics that will be covered in in-class activity sessions will help students develop their essays over the term. ‘PRE’ classes refer to readings and very short activities that must be completed before they come to the in-class sessions.

Figure 1. Essay Writing Framework

- Pre-Class Activity

- In-Class Activity

- Activity Solutions

The Fundamental Components of a Good Essay Structure

A good essay requires a good structure; it needs to be clear and concise, and it needs to integrate ‘signposts’ throughout so that a reader is able to follow the logical argument that the author is making. There is no room for an author’s thoughts to wander away from the purpose of the essay, because such misdirection will lead to the reader becoming confused. To stop this confusion arising, various writing and reading conventions have developed over time. One of these conventions is the internal structure of an academic essay.

This internal structure resembles an ‘ ɪ ’ shape. The top horizontal bar represents the thesis , or part of the essay that will comprise a thesis statement and one or more development statements. The thesis statement is the claim of the argument presented in the essay. Without this, the reader would not know what to expect the rest of the essay to develop. The development statement(s) are also crucial as they tells a reader which points will be used to support the argument, and also which order they will be presented in. If some of these points are not listed – or presented in a different order to the one stated – the reader might fail to understand the author’s intent, or even discount the steps used to support the argument.

The vertical bar of the ‘ ɪ ’ represents the main body of the essay, where each of the points presented in the development part of the thesis should be presented and discussed. Examples and references (citations) are generally included in these paragraphs, but it is important to note that each paragraph should contain only one main idea with examples or references that justify it. This main idea should be presented in a topic sentence at the beginning of the paragraph; these topic sentences act as signposts throughout the main body of the essay.

The bottom horizontal bar of the ‘ ɪ ’ represents the summary/conclusion of the essay. Here the thesis (main claim) and pieces of supporting evidence (different points that developed the argument) are restated briefly to show the reader why/how everything fits together. No new information should be added to the essay at this point.

** Materials adapted from those provided by Joanne Nakonechny, UBC Skylight **

Thesis and Development Statements Recap:

How to write a good thesis statement

Your defining sentence/sentences must clearly state the main idea of your writing. You must include the subject you will discuss and the points that you will make about that subject in the order in which you will write about them.

The value of development statements

These list the different reasons (which will be accompanied with evidence) that the writer is going to use to support his/her claim. These narrowed or more focused points provide the steps of the argument to establish the validity of the thesis statement.

Note that if these reasons are too broad, the essay will be vague, because not all aspects of them can be addressed.

Vague development example:

“Science can solve starvation, disease and crime.”

Stronger development example:

“Science, through genetically modified foods and better crop fertilizers, can contribute to solving starvation.”

Note that this second example provides the reader with information about the specific steps the writer is going to use to support the thesis that science can contribute to solving starvation; genetically modified foods and better crop fertilizers are the reasons that the author is going to expand on to support his/her claim that science can contribute to solving starvation.

Activity 1 (complete before the in-class session)

Throughout these classes, you will develop an argumentative essay in which you state a clear thesis, make claims and supply reasons and evidence to support these reasons, and write a sound conclusion. To begin with, you must:

- Identify a current controversy in science that interests you.

- State your opinion and some of the reasons that you can use as evidence to support your position.

- Come to class prepared to speak about these with a partner.

The Fundamentals of a Good Essay Structure [In-Class Session]

Activity 1 (5 minutes)

Produce short written responses that show:

- One idea in the reading that you already use in your essay writing

- One idea in the reading that you will now use in your essay writing

Activity 2 (10 minutes)

Take part in a class discussion about the structure that a good essay should take. Specifically, think about and discuss:

#What is a thesis statement? #What are development statements? How are they linked to the thesis statement? #What is the purpose of these parts of an essay? #How should the main body of an essay be organized? #What is a topic sentence? Is it the same as a development statement? #What sort of information should appear in the conclusion to an essay?

Activity 3 (10 minutes)

As a general rule, thesis statements in many essays are too general, which means it is not possible for the author to fully address them with reasons and evidence in his/her writing. Stronger thesis statements should provide narrowed or more focused points.

Rank the following four thesis statements (from best to worst) and justify your decisions:

Activity 4 (15 minutes)

In the homework, you were asked to identify a current controversy in science that interests you, and to state your opinion and think of some of the reasons that you could use to support your position.

Choose a partner and briefly speak to them about this (you should both aim to have spoken about your interests and opinions within five minutes).

Now, in the next five minutes, try to write a thesis statement and one or more development statements that you will use to begin your argumentative essay.

And, in the last five minutes, talk to your partner about your thesis statement and development statement(s) and see if you can help each other improve them.

Hint: Are your statements too broad/vague, and do they list enough reasons that you will use to support the main claim made in the thesis statement. Re-writing a thesis statement can take some time, but revision is an important part of the writing process. Try to settle on a good thesis and development statement by the next class but don’t rush things – in many ways, these are the most important parts of an essay.

The suggested solutions of these activities require a password for access. We encourage interested instructors to contact Dr. Jackie Stewart and the ScWRL team to obtain access. Please fill out the Access Request and Feedback Form to inquire about resources you are interested in.

Click here for suggested solutions password protected page for: Activity solutions

Searching the Literature and Including Citations and References

Effective Searching

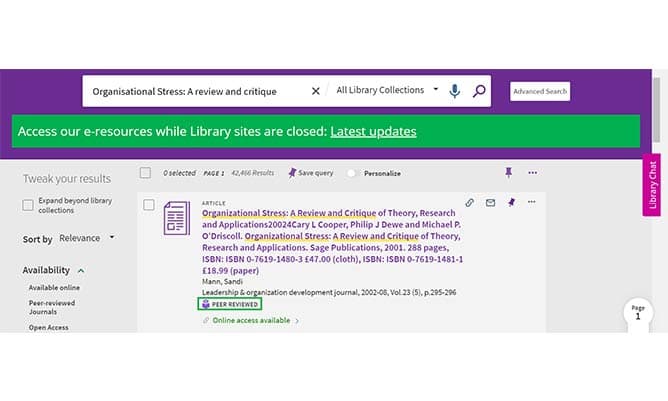

For tips on how to search the literature effectively, to find useful material that could support the development of your essay, and on how to integrate these into your essay, we advise you to read our guides here and here .

Avoiding Plagiarism

Before coming to class, we also ask you to read the following information about plagiarism, so that you know how to identify the different types – and, more importantly, avoid them in your own writing; after all, it is your responsibility to know what plagiarism is and how to avoid it.

To start, review the information in this website link: http://help.library.ubc.ca/planning-your-research/academic-integrity-plagiarism/ , before reading more at this one: http://learningcommons.ubc.ca/resource-guides/avoiding-plagiarism/

You should come to class with an idea about how to avoid each of the three types of plagiarism noted here, ready to participate in a discussion about the main issues. Make some brief notes if you feel they will help you.

Identifying Different Types of Sources

Read the following website link to learn how to differentiate between different types of sources and evaluate how appropriate and useful they are for your essay here: http://help.library.ubc.ca/evaluating-and-citing-sources/evaluating-information-sources/ Make sure you read the information about ‘Primary Sources’ and the related link to ‘Learn about finding…’.

You are also encouraged to watch the following Grammar Squirrel videos to help you solidify these concepts:

- Citing Sources in Science Writing

Make some brief notes on the main differences between primary, secondary and tertiary resources and come to class ready to discuss these.

Searching the Literature

To help you start gathering material for your essay, you should start searching for appropriate literature to support your thesis and the reasons that you are going to develop in the main body of your writing. For a guide on how best to do this, see here .

Before class, find one example of each of primary, secondary and tertiary sources that relate to your essay. On a single sheet of paper, for each resource, write notes on the following, and bring these with you to the in-class session.

- Is this a primary, secondary or tertiary source? Why?

- How might you use this resource in your essay?

For your homework, you were asked to review information about the three main types of plagiarism, and how these can be avoided. You were also asked to read information and watch videos about identifying different types of sources.

Activity 1 (10 minutes)

Take part in a discussion with your classmates and instructor(s) about the three main types of plagiarism. What are they? Have you ever committed any of these before without realizing? How can you avoid plagiarism in your essays?

Activity 2 (15 minutes)

First, take part in a brief discussion with your classmates and instructor(s) about the differences between primary, secondary and tertiary sources. Why are primary sources usually preferred for use in essays and scholarly writing? Are any tertiary sources useful or reliable? Why/why not?

Second, form groups of 4-6 people, and take turns to fill out a table of primary, secondary, and tertiary sources that you each found to support the development of your essays.

When filling out the second column (How might you use this?) , think about how the information contained in this source applies to the scientific controversy that you are writing about; specifically, try to outline how you could use this source to provide a reason and evidence to support the thesis of your argument. You should explain this to your classmates as you fill in the table.

Take part in a discussion with all of your classmates and instructor(s) about the sources that you found. Are they suitable for inclusion in your essays? Why/why not? How are you going to find more sources to help add content depth to your essays?

Activity 4 (10 minutes)

Work with a partner to try to paraphrase some of the information in one of your sources (preferably your primary source); remember the video you watched before class about integrating sources in your work – it is important in science essays to reword what has been written in a source and then attribute the idea to the author(s) of that source.

For now, try to just reword the key information so that it could be included in the main body of your essay. For a more complete guide to attributing the information to the author(s) of the source from which it came, please read the following if you have not already done so: Integrating and Citing Sources .

It is important that you learn the correct format for including citations in your essay, and for compiling the references list at the end.

Click here for suggested solutions password protected page for: Activity Solutions

Paragraph Structure, Topic Sentences and Transitions

Good essays are easy to read and follow a logical development. Structuring the content of your essay in an organized way is thus critical to making sure your reader(s) understand the argument you are making. Even the most content-rich essay can be misinterpreted if it is not structured properly.

A good structure relies upon effective paragraphing. You should try to only include one main content point per paragraph, even if this means some paragraphs are much smaller than others; the key when writing an essay that defends a thesis statement is to use one paragraph for each reason that you present to provide support for your main claim.

Once you have split your essay into discrete paragraphs, you should add in topic sentences to begin each one; these sentences should act as signposts for your reader(s), telling them clearly and succinctly what they can expect to read about in the following paragraph. You can think of them as mini development statements that map the logical development of your essay from paragraph to paragraph.

Finally, you should add in transitions (little words and phrases) that link each sentence together smoothly and make everything easy to read. Words such as ‘initially’, ‘secondly’, ‘however’, ‘furthermore’ and ‘lastly,’ and phrases such as ‘as a result’, ‘on the other hand’ and ‘in addition’ are typical examples that you probably already use on a day-to-day basis.

For more information on effective paragraphing, we advise you to read the following student guide before coming to class: Organizing

Think about the different elements that make a piece of writing effective, and come to class prepared to discuss some of these.

Also, make sure that you bring at least two primary sources that you have found to use in your essay; you will work on writing paragraphs about these with a partner in class.

To prepare you for this class, you should have read the student guide about organizing your writing (how to paragraph effectively). Remember that you must present your essay in a logical way if it is to be interpreted as you mean it to be by your reader(s). A big part of this is invested in writing paragraphs that each present one main idea.

Take part in a class discussion by thinking about the following question: “What makes a good piece of writing?” Hint: Think of as many things as possible (not just those that relate to paragraphing, and structure).

Your instructor will brainstorm the class ideas on the blackboard/whiteboard, but you should do the same so that you can refer to your notes later.

Activity 2 (25 minutes)

Take out the sources that you brought with you (which relate to the current scientific controversy that you are going to discuss in your essay); you should have brought at least two, and these should preferably be primary sources.

Take 10 minutes to write a paragraph about each one so that it could fit into the essay you are writing. Use the brainstorm/notes you took from Activity 1 to help guide your writing. Do not worry too much about writing long paragraphs at this point, but try to make sure you only talk in depth about the one main point of the source you are using in each one.

In the remaining five minutes, try to write a topic sentence for each paragraph; remember that this should act as a mini development statement (or a signpost) that tells a reader what they can expect to read about in the coming paragraph. Lastly, try to add some transition words/phrases to link all the sentences smoothly together.

Make sure you include a citation for your sources (at least one per paragraph)

Activity 3 (15 minutes)

Swap your writing with a partner, and read each other’s work. In the first 10 minutes, make notes on their writing (being constructive) that will help them improve it. Some things to focus on include:

- Is there only one main point per paragraph?

- Does each topic sentence serve as a good signpost? Is it clear from this one sentence alone what the author is going to talk about in that paragraph?

- Does each sentence transition smoothly into the next one?

- Are any of the transition words/phrases confusing?

- Does the writing follow a logical path?

- Are there any confusing terms used (overly complex words, or science jargon)?

- Are the citations formatted correctly?

For the last five minutes, you should take your piece of writing back and begin to improve it based on the feedback your partner gave you. If you do not finish all of these improvements by the end of class, you should complete them as homework; you should try to complete a first draft of your essay soon after this class anyway.

The Importance of Peer Review

When a researcher, or team of researchers, finishes a stage of work, they usually write a paper presenting their methods, findings and conclusions. They then send the paper to a scientific journal to be considered for publication. If the journal’s editor thinks it is suitable for their journal he/she will send the paper to other scientists, who research and publish in the same field and ask them to:

- Comment on its validity – are the research results credible; is the design and methodology appropriate?

- Judge the significance – is it an important finding?

- Determine its originality – are the results new? Does the paper refer properly to work performed by others?

- Give an opinion as to whether the paper should be published, improved or rejected (usually to be submitted elsewhere).

This process is called peer review, and it is incredibly important in making sure that only high-quality written work appears in the literature , but it also allows authors to improve their original work based on the feedback of others.

Did you know?

There are around 21,000 scholarly and scientific journals that use the peer-review system. A high proportion of these are scientific, technical or medical journals, which together publish over 1,000,000 research papers each year.

By the way...

Peer review is also used to assess scientists’ applications for research funds. Funding bodies, such as medical research charities, seek expert advice on a scientist’s proposal before agreeing to pay for it. Peer review in this instance is used to judge which applications have the best potential to help an organization achieve its objectives.

Peer Review – Your Essay

You are not reporting the results of experiments in a journal article or applying for funding, but are writing an essay about a current controversy in science that interests you.

The process of peer review that you will undertake is very similar, however; by hearing what your peers think about your work before you hand it in, you should gain a valuable insight into how they interpret it, and where they think it can be improved. If you make suggested improvements, it is very likely that it will receive a higher grade when you hand it to your instructors.

You already have some experience of the peer-review system, because you provided feedback on a partner’s two paragraphs in the last class, and had them provide you with feedback on your own writing.

For some further tips on how to give effective feedback, make sure you read the following guide before coming to class: How to Give and Receive Effective Feedback , and arrive ready to participate in a discussion about peer review and its importance.

Make sure you also bring a draft of your essay to class; you will be working with a partner to provide feedback on these essays.

Peer review ensures that only high-quality work appears in the science literature; it also allows a writer to improve his/her work based on feedback provided by someone within his/her field. Today you will get the chance to provide constructive feedback on someone else’s essay, while having them comment on yours. This exchange should help you improve your work greatly.

Take part in a class discussion about peer review and its importance. Some specific questions to think about include:

- What would happen if scientists didn't have their work reviewed by their peers?

- Are they any downsides? What happens if there is a disagreement?

- What sort of feedback is the best to give/receive?

Activity 2 (30 minutes)

Choose a partner (preferably someone you haven’t worked with before) and swap your essay drafts. First of all, read through their essay in its entirety before going back and reading it in smaller chunks. Comment on it by annotating the work where you are confused, or where you think improvements can be made. Rather than editing it, suggest other options that would lead to improvements (e.g. don’t make the improvements yourself).

Pay extra attention to the most important elements that dictate whether an essay has a good structure and reads well:

- Are the thesis and development statements clear? Are they too narrow or too broad?

- Is the work split up into paragraphs that focus on one main point each?

- Does the essay follow a logical path of development? Do the reasons that are supplied to support the original thesis follow the order that they were set out in the original development statement(s)?

- Are topic sentences used effectively so that someone who was lost (just started reading halfway through) would understand the route being taken (what the author was going to elaborate on in a given paragraph)?

- Are transition words and phrases used effectively so that each sentence transitions smoothly into the next one?

- Is the conclusion clear and concise? Does the author introduce any new material here that is confusing in any way?

- Is the essay interesting? Do you feel you have learned something new? Do you agree with the thesis statement now that you have read the whole essay (have you been convinced by the author’s argument)?

Read through the comments you have received from your partner and make sure you understand them all. Once you are satisfied that you do, spend the remaining time making improvements based on their feedback. You will not be able to finish all of these in class, but you can take the feedback away with you and use it to improve your essay before handing it in.

Essay Writing Introduction

Essay Structure: Pre-Class Activity | In-Class Activity

Sources and Avoiding Plagiarism: Pre-Class Activity | In-Class Activity

Paragraphing: Pre-Class Activity | In-Class Activity

Peer Review: Pre-Class Activity | In-Class Activity

Click here for suggested solutions password protected page for: Pre-class activity and In-class activity solutions

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER BRIEF

- 08 May 2019

Toolkit: How to write a great paper

A clear format will ensure that your research paper is understood by your readers. Follow:

1. Context — your introduction

2. Content — your results

3. Conclusion — your discussion

Plan your paper carefully and decide where each point will sit within the framework before you begin writing.

Collection: Careers toolkit

Straightforward writing

Scientific writing should always aim to be A, B and C: Accurate, Brief, and Clear. Never choose a long word when a short one will do. Use simple language to communicate your results. Always aim to distill your message down into the simplest sentence possible.

Choose a title

A carefully conceived title will communicate the single core message of your research paper. It should be D, E, F: Declarative, Engaging and Focused.

Conclusions

Add a sentence or two at the end of your concluding statement that sets out your plans for further research. What is next for you or others working in your field?

Find out more

See additional information .

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-01362-9

Related Articles

How to get published in high impact journals

So you’re writing a paper

Writing for a Nature journal

Overcoming low vision to prove my abilities under pressure

Career Q&A 28 MAR 24

How a spreadsheet helped me to land my dream job

Career Column 28 MAR 24

Maple-scented cacti and pom-pom cats: how pranking at work can lift lab spirits

Career Feature 27 MAR 24

Postdoc Research Associates in Single Cell Multi-Omics Analysis and Molecular Biology

The Cao Lab at UT Dallas is seeking for two highly motivated postdocs in Single Cell Multi-Omics Analysis and Molecular Biology to join us.

Dallas, Texas (US)

the Department of Bioengineering, UT Dallas

Expression of Interest – Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions – Postdoctoral Fellowships 2024 (MSCA-PF)

Academic institutions in Brittany are looking for excellent postdoctoral researchers willing to apply for a Marie S. Curie Postdoctoral Fellowship.

France (FR)

Plateforme projets européens (2PE) -Bretagne

Tenure-track Assistant Professor in Ecological and Evolutionary Modeling

Tenure-track Assistant Professor in Ecosystem Ecology linked to IceLab’s Center for modeling adaptive mechanisms in living systems under stress

Umeå, Sweden

Umeå University

Faculty Positions in Westlake University

Founded in 2018, Westlake University is a new type of non-profit research-oriented university in Hangzhou, China, supported by public a...

Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Westlake University

Postdoctoral Fellowships-Metabolic control of cell growth and senescence

Postdoctoral positions in the team Cell growth control by nutrients at Inst. Necker, Université Paris Cité, Inserm, Paris, France.

Paris, Ile-de-France (FR)

Inserm DR IDF Paris Centre Nord

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

How to Write a Scientific Essay

When writing any essay it’s important to always keep the end goal in mind. You want to produce a document that is detailed, factual, about the subject matter and most importantly to the point.

Writing scientific essays will always be slightly different to when you write an essay for say English Literature . You need to be more analytical and precise when answering your questions. To help achieve this, you need to keep three golden rules in mind.

- Analysing the question, so that you know exactly what you have to do

Planning your answer

- Writing the essay

Now, let’s look at these steps in more detail to help you fully understand how to apply the three golden rules.

Analysing the question

- Start by looking at the instruction. Essays need to be written out in continuous prose. You shouldn’t be using bullet points or writing in note form.

- If it helps to make a particular point, however, you can use a diagram providing it is relevant and adequately explained.

- Look at the topic you are required to write about. The wording of the essay title tells you what you should confine your answer to – there is no place for interesting facts about other areas.

The next step is to plan your answer. What we are going to try to do is show you how to produce an effective plan in a very short time. You need a framework to show your knowledge otherwise it is too easy to concentrate on only a few aspects.

For example, when writing an essay on biology we can divide the topic up in a number of different ways. So, if you have to answer a question like ‘Outline the main properties of life and system reproduction’

The steps for planning are simple. Firstly, define the main terms within the question that need to be addressed. Then list the properties asked for and lastly, roughly assess how many words of your word count you are going to allocate to each term.

Writing the Essay

The final step (you’re almost there), now you have your plan in place for the essay, it’s time to get it all down in black and white. Follow your plan for answering the question, making sure you stick to the word count, check your spelling and grammar and give credit where credit’s (always reference your sources).

How Tutors Breakdown Essays

An exceptional essay

- reflects the detail that could be expected from a comprehensive knowledge and understanding of relevant parts of the specification

- is free from fundamental errors

- maintains appropriate depth and accuracy throughout

- includes two or more paragraphs of material that indicates greater depth or breadth of study

A good essay

An average essay

- contains a significant amount of material that reflects the detail that could be expected from a knowledge and understanding of relevant parts of the specification.

In practice this will amount to about half the essay.

- is likely to reflect limited knowledge of some areas and to be patchy in quality

- demonstrates a good understanding of basic principles with some errors and evidence of misunderstanding

A poor essay

- contains much material which is below the level expected of a candidate who has completed the course

- Contains fundamental errors reflecting a poor grasp of basic principles and concepts

Privacy Overview

School of Biological Sciences

University of Manchester

Tutorial – Appendix 2: A Practical Guide to Writing Essays – Level 1

Appendix 2: a practical guide to writing essays.

Writing an essay is a big task that will be easier to manage if you break it down into five main tasks as shown below:

An essay-writing Model in 5 steps

- Analyse the question

What is the topic?

What are the key verbs?

Question the question—brainstorm and probe

What information do you need?

How are you going to find information?

Find the information

Make notes and/or mind maps

- Plan and sort

Arrange information in a logical structure

Plan sections and paragraphs

Introduction and conclusion

- Edit (and proofread)

For sense and logical flow

For grammar and spelling

My Learning Essentials offers a number of online resources and workshops that will help you to, understand the importance of referencing your sources, use appropriate language and style in your writing, write and proofread your essays. For more information visit the writing skills My Learning Essentials pages: http://www.library.manchester.ac.uk/services-and-support/students/support-for-your-studies/my-learning-essentials/

1. Analyse the question

Many students write great essays — but not on the topic they were asked about. First, look at the main idea or topic in the question. What are you going to be writing about? Next, look at the verb in the question — the action word. This verb, or action word, is asking you to do something with the topic.

Here are some common verbs or action words and explanations:

2. Research

Once you have analysed the question, start thinking about what you need to find out. It’s better and more efficient to have a clear focus for your research than to go straight to the library and look through lots of books that may not be relevant.

Start by asking yourself, ‘What do I need to find out?’ Put your ideas down on paper. A mind map is a good way to do this. Useful questions to start focusing your research are: What? Why? When? How? Where? Who?

My Learning Essentials offer a number of online resources and workshops to help you to plan your research. Visit the My Learning Essentials page: http://www.library.manchester.ac.uk/services-and-support/students/support-for-your-studies/my-learning-essentials/workshops-and-online-resources/

3. Plan and sort

First, scan through your source . Find out if there’s any relevant information in what you are reading. If you’re reading a book, look at the contents page, any headings, and the index. Stick a Post-It note on useful pages.

Next, read for detail . Read the text to get the information you want. Start by skimming your eyes over the page to pick our relevant headings, summaries, words. If it’s useful, make notes.

Making notes

There are two rules when you are making notes:

- page reference

- date of publication

- publisher’s name (book)

- place where it was published (book or journal)

- the journal number, volume and date (journal)

- Make brief notes rather than copy text, but if you feel an extract is very valuable put it in quotation marks so that when you write your essay, you’ll know that you have to put it in your own words. Failing to rewrite the text in your own words would be plagiarism.

For more information on plagiarism, refer to the semester 1 section of this handbook, the First Level Handbook, and the My Learning Essentials Plagiarism Resource http://libassets.manchester.ac.uk/mle/avoiding-plagiarism/

Everyone will make notes differently and as it suits them. However, the aim of making notes when you are researching an essay is to use them when you write the essay. It is therefore important that you can:

- Read your notes

- Find their source

- Determine what the topics and main points are on each note (highlight the main ideas, key points or headings).

- Compose your notes so you can move bits of information around later when you have to sort your notes into an essay.

For example:

- Write/type in chunks (one topic for one chunk) with a space between them so you can cut your notes up later, or

- write the main topics or questions you want to answer on separate pieces of paper before you start making notes. As you find relevant information, write it on the appropriate page. (This takes longer as you have to write the source down a number of times, but it does mean you have ordered your notes into headings.)

Sort information into essay plans

You’ve got lots of information now: how do you put it all together to make an essay that makes sense? As there are many ways to sort out a huge heap of clothes (type of clothes, colour, size, fabric…), there are many ways of sorting information. Whichever method you use, you are looking for ways to arrange the information into groups and to order the groups into a logical sequence . You need to play around with your notes until you find a pattern that seems right and will answer the question.

- Find the main points in your notes, put them on a separate page – a mind map is a good way to do this – and see if your main points form any patterns or groups.

- Is there a logical order? Does one thing have to come after another? Do points relate to one another somehow? Think about how you could link the points.

- Using the information above, draw your essay plan. You could draw a picture, a mind map, a flow chart or whatever you want. Or you could build a structure by using bits of card that you can move around.

- Select and put the relevant notes into the appropriate group so you are ready to start writing your first draft.

The essay has four main parts:

- introduction

- references.

People usually write the introduction and conclusion after they have written the main body of the essay, so we have covered the essay components in that order below.

For more information on essay writing visit the My Learning Essentials web pages:

http://www.library.manchester.ac.uk/services-and-support/students/support-for-your-studies/my-learning-essentials/workshops-and-online-resources/?level=3&level1Link=3&level2Links=writing

Structure . The main body should have a clear structure. Depending on the length of the essay, you may have just a series of paragraphs, or sections with headings, or possibly even subsections. In the latter case, make sure that the hierarchy of headings is obvious so that the reader doesn’t get lost.

Flow . The main body of the essay answers the question and flows logically from one key point to another (each point needs to be backed up by evidence [experiments, research, texts, interviews, etc …] that must be referenced). You should normally write one main idea per paragraph and the main ideas in your essay should be linked or ‘signposted’. Signposts show readers where they are going, so they don’t get lost. This lets the reader know how you are going to tackle the idea, or how one idea is linked with the one before it or after it.

Some signpost words and phrases are:

- ‘These changes . . . “

- ‘Such developments

- ‘This

- ‘In the first few paragraphs . . . “

- ‘I will look in turn at. . . ‘

- ‘However, . . . “

- ‘Similarly’

- ‘But’.

Figures: purpose . You should try to include tables, diagrams, and perhaps photographs in your essay. Tables are valuable for summarising information, and are most likely to impress if they show the results of relevant experimental data. Diagrams enable the reader to visualise things, replacing the need for lengthy descriptions. Photographs must be selected with care, to show something meaningful. Nobody will be impressed by a picture of a giraffe – we all know what one looks like, so the picture would be mere decoration. But a detailed picture of a giraffe’s markings might be useful if it illustrates a key point.

Figures: labelling, legends and acknowledgment . Whenever you use a table, diagram or image in your essay you must:

- cite the source

- write a legend (a small box of text that describes the content of the figure).

- make sure that the legend and explanation are adapted to your purpose.

For example: Figure 1. The pathway of synthesis of the amino acid alanine, showing… From Bloggs (1989). [When using a figure originally produced by someone else, never use the original legend, because it is likely to have a different Figure number and to have information that is not relevant for your purposes. Also, make sure that you explain any abbreviations or other symbols that your reader needs to know about the Figure, including details of different colours if they are used to highlight certain aspects of the Figure].

Checklist for the main body of text

- Does your text have a clear structure?

- Does the text follow a logical sequence so that the argument flows?

- Does your text have both breadth and depth – i.e. general coverage of the major issues with in-depth treatment of particularly important points?

- Does your text include some illustrative experimental results?

- Have you chosen the diagrams or photographs carefully to provide information and understanding, or are the illustrations merely decorative?

- Are your figures acknowledged properly? Did you label them and include legend and explanation?

Introduction

The introduction comes at the start of the essay and sets the scene for the reader. It usually defines clearly the subject you will address (e.g. the adaptations of organisms to cold environments), how you will address this subject (e.g. by using examples drawn principally from the Arctic zone) and what you will show or argue (e.g. that all types of organism, from microbes through to mammals, have specific adaptations that fit them for life in cold environments). The length of an introduction depends on the length of your essay, but is usually between 50 to 200 words.

Remember that reading the introduction constitutes the first impression on your reader (i.e. your assessor). Therefore, it should be the last section that you revise at the editing stage, making sure that it leads the reader clearly into the details of the subject you have covered and that it is completely free of typos and spelling mistakes.

Check-list for the Introduction

- Does your introduction start logically by telling the reader what the essay is about – for example, the various adaptations to habitat in the bear family?

- Does your introduction outline how you will address this topic – for example, by an overview of the habitats of bears, followed by in-depth treatment of some specific adaptations?

- Is it free of typos and spelling mistakes?

Conclusion

An essay needs a conclusion. Like the introduction, this need not be long: 50 to 200 words is sufficient, depending on the length of the essay. It should draw the information together and, ideally, place it in a broader context by personalising the findings, stating an opinion or supporting a further direction which may follow on from the topic. The conclusion should not introduce facts in addition to those in the main body.

Check-list for the Conclusion

- Does your conclusion sum up what was said in the main body?

- If the title of the essay was a question, did you give a clear answer in the conclusion?

- Does your conclusion state your personal opinion on the topic or its future development or further work that needs to be done? Does it show that you are thinking further?

In all scientific writing you are expected to cite your main sources of information. Scientific journals have their own preferred (usually obligatory) method of doing this. The piece of text below shows how you can cite work in an essay, dissertation or thesis. Then you supply an alphabetical list of references at the end of the essay. The Harvard style of referencing adopted at the University of Manchester will be covered in the Writing and Referencing Skills unit in semester 2. For more information refer to the Referencing Guide from the University Library (http://subjects.library.manchester.ac.uk/referencing/referencing-harvard).

Citations in the text

Jones and Smith (1999) showed that the ribosomal RNA of fungi differs from that of slime moulds. This challenged the previous assumption that slime moulds are part of the fungal kingdom (Toby and Dean, 1987). However, according to Bloggs et al . (1999) the slime moulds can still be accommodated in the fungal kingdom for convenience. Slime moulds are considered part of the Eucarya domain by Todar (2012).

Reference list at the end of the essay:

List the references in alphabetical order and if you have several publications written by the same author(s) in the same year, add a letter (a,b,c…) after the year to distinguish between them.

Bloggs, A.E., Biggles, N.H. and Bow, R.T. (1999). The Slime Moulds . 2 nd edn. London and New York: Academic Press.

[ Guidance: this reference is to a book. We give the names of all authors, the publication date, title, name of publisher and place of publication. Note that we referred to Bloggs et al .(1999) in the text. The term “ et al .” is an abbreviation of the Latin et alia (meaning “and others”). Note also that within the text “Bloggs et al .” is part of a sentence, so we put only the date in parentheses for the citation in the text. If you wish to cite the entire book, then no page numbers are listed. To cite a specific portion of a book, page numbers are added following the book title in the reference list (see Toby and Dean below).

Todar K. (2012) Overview Of Bacteriology. Available at: http://textbookofbacteriology.net, [Accessed 15 November 2013].

Jones, B.B. and Smith, J.O.E. (1999). Ribosomal RNA of slime moulds, Journal of Ribosomal RNA 12, 33-38.

Toby F.S. and Dean P.L. (1987). Slime moulds are part of the fungal kingdom, in Edwards A.E. and Kane Y. (eds.) The Fungal Kingdom. Luton: Osbert Publishing Co., pp. 154-180 .

EndNote: This is an electronic system for storing and retrieving references. It is very powerful and simple to use, but you must always check that the output is consistent with the instructions given in this section. EndNote will be covered (and assessed) in the Writing and Referencing Skills online unit in Semester 2 to help you research and reference your written work.

Visit the My Learning Essentials online resource for a guide to using EndNote: https://www.escholar.manchester.ac.uk/learning-objects/mle/endnote-guide/ (we recommend EndNote online if you wish to use your own computer).

Note that journals have their own house style so there will be minor differences between them, particularly in their use of punctuation, but all reference lists for the same journal will be in the same format.

First Draft

When you write your first draft, keep two things in mind:

- Length: you may lose marks if your essay is too long. Ensure therefore that your essay is within the page limit that has been set.

- Expression: don’t worry about such matters as punctuation, spelling or grammar at this stage. You can get this right at the editing stage. If you put too much time into getting these things right at the drafting stage, you will have less time to spend on thinking about the content, and you will be less willing to change it when you edit for sense and flow at the editing stage.

Writing style

The style of your essay should fit the task or the questions asked and be targeted to your reader. Just as you are careful to use the correct tone of voice and language in different situations so you must take care with your writing. Generally writing should be:

- Make sure that you write exactly what you mean in a simple way.

- Write briefly and keep to the point. Use short sentences. Make sure that the meaning of your sentences is obvious.

- Check that you would feel comfortable reading your essay if you were actually the reader.

- Make sure that you have included everything of importance. Take care to explain or define any abbreviations or specialised jargon in full before using a shortened version later. Do not use slang, colloquialisms or cliches in formal written work.

When you are editing your essay, you will need to bear in mind a number of things. The best way to do this, without forgetting something, is to edit in ‘layers’, using a check-list to make sure you have not forgotten anything.

Check-list for Style

- Tone – is it right for the purpose and the receiver?

- Clarity – is it simple, clear and easy to understand?

- Complete – have you included everything of importance?

Check-list for Sense

- Does your essay make sense?

- Does it flow logically?

- Have you got all the main points in?

- Are there bits of information that aren’t useful and need to be deleted?

- Are your main ideas in paragraphs?

- Are the paragraphs linked to one another so that the essay flows rather than jumps from one thing to another?

- Is the essay within the page limit?

Check-list for Proofreading

- Are the punctuation, grammar, spelling and format correct?

- If you have written your essay on a word-processor, run the spell check over it.

- Have you referenced all quotes and names correctly?

- Is the essay written in the correct format? (one and a half line spacing, margins at least 2.5cm all around the text, minimum font size 10 point).

School Writer in Residence

The School has three ‘Writers in Residence’ who are funded by The Royal Literary Fund.

Susan Barker – Monday and Friday

Tania Hershman – Tuesday

Katherine Clements – Wednesday and Thursday

The Writers in Residence are based in the Simon Building. Please see the BIOL10000 Blackboard site for further information about the writers’ expertise and instructions for appointment booking.

- ← Tutorial – Appendix 5: A practical guide to writing essays – Level 2

- Tutorial Guide – Employability Skills P2 – Level 2 →

Tips for writing a first-class essay

- Tuesday, April 13, 2021

- Undergraduate

Chloe Softly

- United Kingdom

- minute read

As a final year student, I have noticed huge developments in my academic writing and ultimately would like to share a few wise words on what I think has helped me to achieve first-class essay marks.

Firstly, how will we ever get a first without being aware of what is expected? We need to get to know the mark scheme. A great way of guaranteeing we are achieving all the key elements of the mark scheme, is to align our initial plan with each point of the criteria and keep checking throughout our essay writing to assure all areas are being covered.

Another BIG thing is always to make sure you understand the question. Now I hope this doesn’t sound patronising, but it is so important to read, read and read the question again to fully understand. A main part of understanding fully includes evaluating the action phrase in the question, so make sure you know what is required when you see phrases such as ‘Describe’ and ‘Critically Analyse’.

Along with understanding the question, we need to be able to answer it effectively, and the best way to do this is through the structure. Within academic writing it is vital to frame your argument coherently so the essay flows from paragraph to paragraph. A massive factor in enabling this stems from our essay structure outlined in the introduction. A thing I like to do after finishing my essay is putting a tick next to each paragraph if it matches with this initial outlined structure to guarantee that the essay flows.

The final tip I have is to make sure your references reflect the depth of your knowledge. I always include references from the core and further reading lists, but also carry out additional reading to provide my markers with new perceptions. They want to learn from us! In order to find new sources, I make sure to use the University of Manchester Library, to certify these sources are credible (Peer-Reviewed). With some essays you may end up having a multitude of sources that can be difficult to organise, so one way that I handle this is by creating a table that consists of three columns: one for the main argument, one for the supporting evidence, and one for the source citation. This presents me with a simple method of creating a bibliography, without adding extra pressure to myself.

Although these tips may be useful, we cannot ignore the abundance of resources that are available to assist us. One great resource is the ‘Academic Phrasebank’, a document put together by Dr. John Morley at the University of Manchester, that provides insights into how to succeed within your academic writing. From providing notes on essay structure, grammar, and most essential key phrases, this document has become an indispensable guide to me. All in all, from mark schemes to structure to sources, these are just a few tips that will hopefully help. It’s time to go get that first!

I am Chloe Softly, follow my blogs for an insight into life as an Undergraduate student at Alliance MBS.

- Download our brochure

- Chat to a student

- Undergraduate courses

Related blogs

- Reducing stress during exam results season Thursday, July 21, 2022

- Life as a student at Alliance Manchester Business School Thursday, July 21, 2022

- An international penultimate year student summer schedule Thursday, July 21, 2022

The War at Stanford

I didn’t know that college would be a factory of unreason.

Listen to this article

Produced by ElevenLabs and News Over Audio (NOA) using AI narration.

This article was featured in the One Story to Read Today newsletter. Sign up for it here .

ne of the section leaders for my computer-science class, Hamza El Boudali, believes that President Joe Biden should be killed. “I’m not calling for a civilian to do it, but I think a military should,” the 23-year-old Stanford University student told a small group of protesters last month. “I’d be happy if Biden was dead.” He thinks that Stanford is complicit in what he calls the genocide of Palestinians, and that Biden is not only complicit but responsible for it. “I’m not calling for a vigilante to do it,” he later clarified, “but I’m saying he is guilty of mass murder and should be treated in the same way that a terrorist with darker skin would be (and we all know terrorists with dark skin are typically bombed and drone striked by American planes).” El Boudali has also said that he believes that Hamas’s October 7 attack was a justifiable act of resistance, and that he would actually prefer Hamas rule America in place of its current government (though he clarified later that he “doesn’t mean Hamas is perfect”). When you ask him what his cause is, he answers: “Peace.”

I switched to a different computer-science section.

Israel is 7,500 miles away from Stanford’s campus, where I am a sophomore. But the Hamas invasion and the Israeli counterinvasion have fractured my university, a place typically less focused on geopolitics than on venture-capital funding for the latest dorm-based tech start-up. Few students would call for Biden’s head—I think—but many of the same young people who say they want peace in Gaza don’t seem to realize that they are in fact advocating for violence. Extremism has swept through classrooms and dorms, and it is becoming normal for students to be harassed and intimidated for their faith, heritage, or appearance—they have been called perpetrators of genocide for wearing kippahs, and accused of supporting terrorism for wearing keffiyehs. The extremism and anti-Semitism at Ivy League universities on the East Coast have attracted so much media and congressional attention that two Ivy presidents have lost their jobs. But few people seem to have noticed the culture war that has taken over our California campus.

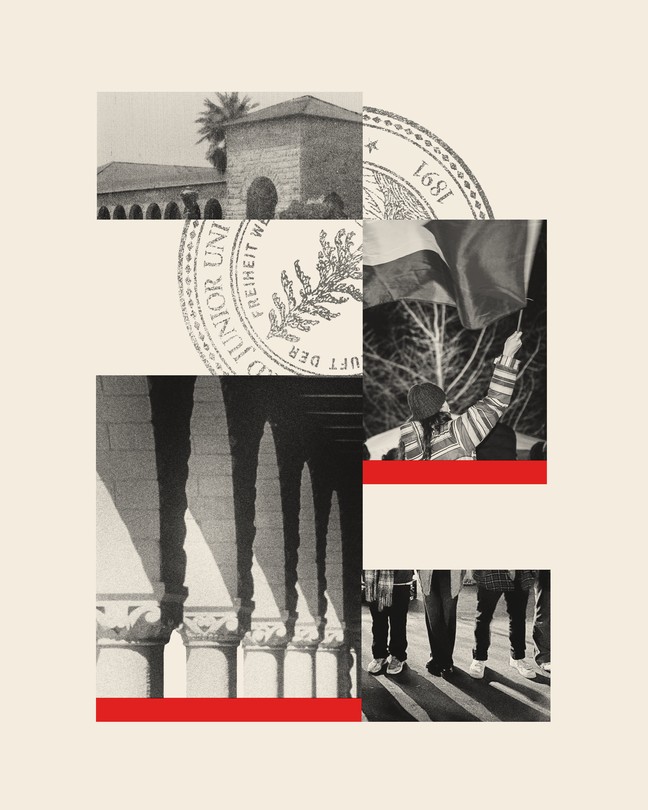

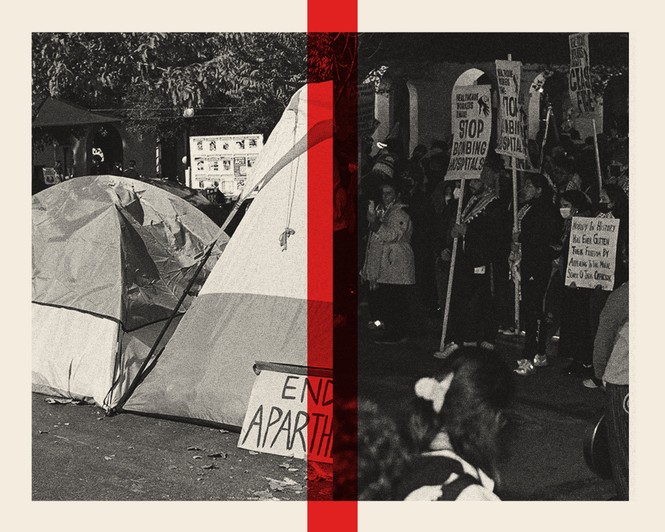

For four months, two rival groups of protesters, separated by a narrow bike path, faced off on Stanford’s palm-covered grounds. The “Sit-In to Stop Genocide” encampment was erected by students in mid-October, even before Israeli troops had crossed into Gaza, to demand that the university divest from Israel and condemn its behavior. Posters were hung equating Hamas with Ukraine and Nelson Mandela. Across from the sit-in, a rival group of pro-Israel students eventually set up the “Blue and White Tent” to provide, as one activist put it, a “safe space” to “be a proud Jew on campus.” Soon it became the center of its own cluster of tents, with photos of Hamas’s victims sitting opposite the rubble-ridden images of Gaza and a long (and incomplete) list of the names of slain Palestinians displayed by the students at the sit-in.

Some days the dueling encampments would host only a few people each, but on a sunny weekday afternoon, there could be dozens. Most of the time, the groups tolerated each other. But not always. Students on both sides were reportedly spit on and yelled at, and had their belongings destroyed. (The perpetrators in many cases seemed to be adults who weren’t affiliated with Stanford, a security guard told me.) The university put in place round-the-clock security, but when something actually happened, no one quite knew what to do.

Conor Friedersdorf: How October 7 changed America’s free speech culture

Stanford has a policy barring overnight camping, but for months didn’t enforce it, “out of a desire to support the peaceful expression of free speech in the ways that students choose to exercise that expression”—and, the administration told alumni, because the university feared that confronting the students would only make the conflict worse. When the school finally said the tents had to go last month, enormous protests against the university administration, and against Israel, followed.

“We don’t want no two states! We want all of ’48!” students chanted, a slogan advocating that Israel be dismantled and replaced by a single Arab nation. Palestinian flags flew alongside bright “Welcome!” banners left over from new-student orientation. A young woman gave a speech that seemed to capture the sense of urgency and power that so many students here feel. “We are Stanford University!” she shouted. “We control things!”

“W e’ve had protests in the past,” Richard Saller, the university’s interim president, told me in November—about the environment, and apartheid, and Vietnam. But they didn’t pit “students against each other” the way that this conflict has.

I’ve spoken with Saller, a scholar of Roman history, a few times over the past six months in my capacity as a student journalist. We first met in September, a few weeks into his tenure. His predecessor, Marc Tessier-Lavigne, had resigned as president after my reporting for The Stanford Daily exposed misconduct in his academic research. (Tessier-Lavigne had failed to retract papers with faked data over the course of 20 years. In his resignation statement , he denied allegations of fraud and misconduct; a Stanford investigation determined that he had not personally manipulated data or ordered any manipulation but that he had repeatedly “failed to decisively and forthrightly correct mistakes” from his lab.)

In that first conversation, Saller told me that everyone was “eager to move on” from the Tessier-Lavigne scandal. He was cheerful and upbeat. He knew he wasn’t staying in the job long; he hadn’t even bothered to move into the recently vacated presidential manor. In any case, campus, at that time, was serene. Then, a week later, came October 7.

The attack was as clear a litmus test as one could imagine for the Middle East conflict. Hamas insurgents raided homes and a music festival with the goal of slaughtering as many civilians as possible. Some victims were raped and mutilated, several independent investigations found. Hundreds of hostages were taken into Gaza and many have been tortured.

This, of course, was bad. Saying this was bad does not negate or marginalize the abuses and suffering Palestinians have experienced in Gaza and elsewhere. Everyone, of every ideology, should be able to say that this was bad. But much of this campus failed that simple test.

Two days after the deadliest massacre of Jews since the Holocaust, Stanford released milquetoast statements marking the “moment of intense emotion” and declaring “deep concern” over “the crisis in Israel and Palestine.” The official statements did not use the words Hamas or violence .

The absence of a clear institutional response led some teachers to take matters into their own hands. During a mandatory freshman seminar on October 10, a lecturer named Ameer Loggins tossed out his lesson plan to tell students that the actions of the Palestinian “military force” had been justified, that Israelis were colonizers, and that the Holocaust had been overemphasized, according to interviews I conducted with students in the class. Loggins then asked the Jewish students to identify themselves. He instructed one of them to “stand up, face the window, and he kind of kicked away his chair,” a witness told me. Loggins described this as an effort to demonstrate Israel’s treatment of Palestinians. (Loggins did not reply to a request for comment; a spokesperson for Stanford said that there were “different recollections of the details regarding what happened” in the class.)

“We’re only in our third week of college, and we’re afraid to be here,” three students in the class wrote in an email that night to administrators. “This isn’t what Stanford was supposed to be.” The class Loggins taught is called COLLEGE, short for “Civic, Liberal, and Global Education,” and it is billed as an effort to develop “the skills that empower and enable us to live together.”

Loggins was suspended from teaching duties and an investigation was opened; this angered pro-Palestine activists, who organized a petition that garnered more than 1,700 signatures contesting the suspension. A pamphlet from the petitioners argued that Loggins’s behavior had not been out of bounds.

The day after the class, Stanford put out a statement written by Saller and Jenny Martinez, the university provost, more forcefully condemning the Hamas attack. Immediately, this new statement generated backlash.

Pro-Palestine activists complained about it during an event held the same day, the first of several “teach-ins” about the conflict. Students gathered in one of Stanford’s dorms to “bear witness to the struggles of decolonization.” The grievances and pain shared by Palestinian students were real. They told of discrimination and violence, of frightened family members subjected to harsh conditions. But the most raucous reaction from the crowd was in response to a young woman who said, “You ask us, do we condemn Hamas? Fuck you!” She added that she was “so proud of my resistance.”

David Palumbo-Liu, a professor of comparative literature with a focus on postcolonial studies, also spoke at the teach-in, explaining to the crowd that “European settlers” had come to “replace” Palestine’s “native population.”

Palumbo-Liu is known as an intelligent and supportive professor, and is popular among students, who call him by his initials, DPL. I wanted to ask him about his involvement in the teach-in, so we met one day in a café a few hundred feet away from the tents. I asked if he could elaborate on what he’d said at the event about Palestine’s native population. He was happy to expand: This was “one of those discussions that could go on forever. Like, who is actually native? At what point does nativism lapse, right? Well, you haven’t been native for X number of years, so …” In the end, he said, “you have two people who both feel they have a claim to the land,” and “they have to live together. Both sides have to cede something.”

The struggle at Stanford, he told me, “is to find a way in which open discussions can be had that allow people to disagree.” It’s true that Stanford has utterly failed in its efforts to encourage productive dialogue. But I still found it hard to reconcile DPL’s words with his public statements on Israel, which he’d recently said on Facebook should be “the most hated nation in the world.” He also wrote: “When Zionists say they don’t feel ‘safe’ on campus, I’ve come to see that as they no longer feel immune to criticism of Israel.” He continued: “Well as the saying goes, get used to it.”

Z ionists, and indeed Jewish students of all political beliefs, have been given good reason to fear for their safety. They’ve been followed, harassed, and called derogatory racial epithets. At least one was told he was a “dirty Jew.” At least twice, mezuzahs have been ripped from students’ doors, and swastikas have been drawn in dorms. Arab and Muslim students also face alarming threats. The computer-science section leader, El Boudali, a pro-Palestine activist, told me he felt “safe personally,” but knew others who did not: “Some people have reported feeling like they’re followed, especially women who wear the hijab.”

In a remarkably short period of time, aggression and abuse have become commonplace, an accepted part of campus activism. In January, Jewish students organized an event dedicated to ameliorating anti-Semitism. It marked one of Saller’s first public appearances in the new year. Its topic seemed uncontroversial, and I thought it would generate little backlash.

Protests began before the panel discussion even started, with activists lining the stairs leading to the auditorium. During the event they drowned out the panelists, one of whom was Israel’s special envoy for combatting anti-Semitism, by demanding a cease-fire. After participants began cycling out into the dark, things got ugly.

Activists, their faces covered by keffiyehs or medical masks, confronted attendees. “Go back to Brooklyn!” a young woman shouted at Jewish students. One protester, who emerged as the leader of the group, said that she and her compatriots would “take all of your places and ensure Israel falls.” She told attendees to get “off our fucking campus” and launched into conspiracy theories about Jews being involved in “child trafficking.” As a rabbi tried to leave the event, protesters pursued him, chanting, “There is only one solution! Intifada revolution!”