Internet Addiction

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

More a popular idea than a scientifically valid concept, internet addiction is the belief that people can become so dependent on using their mobile phones or other electronic devices that they lose control of their own behavior and suffer negative consequences. The harm is alleged to stem both from direct involvement with the device—something that has never been proven—and from the abandonment of other activities, such as studying, face-to-face socializing, or sleep.

- What Is Internet Addiction?

- Signs of Excessive Internet Use

- Internet Use and Mental Health

- What to Do About Internet Addiction

There is much debate in the scientific community about whether excessive internet use can be classified as a true addiction. In an addiction to substances such as drugs or alcohol , consumption ceases being pleasurable but continues and is difficult to escape even as the likelihood of harm to the body and life mounts. In the case of internet use, there is no clear point at which being online becomes non-pleasurable for most individuals. In part for this reason, behavioral "addictions," including using the internet, remain controversial: Experts debate where the line should be drawn between passionate absorption in any activity—say, devoting a lot of time to playing the cello or reading books—and being stuck in a rut of compulsivity that stops being useful and detrimentally affects other areas of life.

In preparing the current edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders , psychiatrists and other experts debated whether to include internet addiction. They decided that there was not enough scientific evidence to support inclusion at this time, although the DSM-5 does recognize Internet Gaming Disorder as a condition warranting further study.

Most often, the word “addiction” is used in the colloquial sense. Common Sense Media finds that 59 percent of parents “feel” their kids are addicted to their mobile devices—just as 27 percent of the parents feel that they themselves are. Sixty-nine percent of parents say they check their own devices at least hourly, as do 78 percent of teens. Spending a lot of time on the internet is increasingly considered normal behavior, especially for adolescents. Much of their social activity has simply moved online. Like any new technology, the computer has changed the way everyone lives, learns, and communicates. It is possible to be online far too much, even though this does not constitute a true addiction in the eyes of most clinicians.

Internet content creators leverage the ways in which the brain works to rally consumers ' attention . One simple example: A perceived threat activates your fight-or-flight response, a part of the brain known as the Reticular Activating System mobilizes the body for action. So online content exploits potential dangers—violence, natural disaster, disease, etc.—to attract and hold your attention.

Problematic or excessive internet use can indeed pose a serious problem. It can displace such important needs as sleep, homework, and exercise, often a source of friction between parents and teens. It can have negative effects on real-life relationships.

The idea of internet addiction is a particular concern among parents, who worry about the harmful effects of screen time and often argue about device use with their children. According to a 2019 survey conducted by Common Sense Media, children aged 8 to 12 now spend 5 hours a day on digital devices, while teens clock more than 7 hours—not including schoolwork. Teen screen time is slowly ticking upward, and most teens take their phones to bed with them.

Whether classified as an addiction or not, heavy use of technology can be detrimental. It can impair focus, resulting in poor performance at school or work. Excessive internet consumption also makes it more difficult for people to communicate normally or to regulate their emotions. They spend less time on non-internet-related activities at the cost of relationships with friends, family, and significant others.

One way to assess whether you’re using the internet too much is to ask yourself if your basics needs (or your child’s, if they are the concern) are being met. Do you sleep enough, eat healthy, get enough exercise, enjoy the outdoors, and spend time socializing in-person? The real harm of screen time may lie in missed opportunities for growth and connection.

Excessive screen time can be particularly harmful to a developing brain: It decreases focus and attention span while increasing the need for more constant stimulation and instant gratification. Those who use the internet excessively may feel anxious if their access to their device gets restricted. They tend to be more impulsive and struggle to recognize facial and nonverbal cues in real life.

Internet use becomes a problem when people start substituting online connections for real, physical relationships. The effects of technology on relationships include increased isolation and loneliness . Defaulting to online communication also denies us the opportunity to hear someone’s voice and read their facial cues in-person; it can also lead to poorer outcomes and miscommunication. Experts recommend that we save the important conversations for when we can be face-to-face for just this reason.

Online content has been designed to elicit specific “checking habits,” which can result in distraction and poor performance at school or work. Constantly checking your smartphone or another device can also lead to relationship-sabotaging behaviors, like phubbing (snubbing loved ones for the instant gratification of checking the internet on your device). As more time is spent online, less is devoted to the natural pleasures of everyday life.

Excessive use of the internet is known to negatively impact a person’s mental health. It has been associated with mental health issues, such as loneliness, depression , anxiety , and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Research suggests that people are likely to use the internet more as an emotional crutch to cope with negative feelings instead of addressing them in proactive and healthy ways.

This is a subject of debate at present. While internet addiction is not in the DSM-V, it is clearly a behavior that negatively impacts mental health and cognition for many, and many struggle to cut back on their time online. The term "addiction" is often used as a shorthand for, “My child spends a lot of time on social media , texting friends, or playing video games, and I’m worried how it will affect his or her future development and success.” At the same time, many people label it a behavioral addiction, engaging reward circuitry seen in other problematic behaviors such as gambling.

Time online is also sometimes used as an escape from boredom or relief from loneliness or other unpleasantness. Occasionally, excessive screen time masks a state of depression or anxiety. In such cases, digital engagement becomes an attempt to remedy the feelings of distress caused by true mental health disorders that could likely benefit from professional or other attention.

Given how much people rely on technology to complete everyday tasks, from online schooling to paying bills to ordering food to keeping in touch with loved ones who are far away, it isn’t feasible to stop using the internet altogether. In most cases, the goal should be to reduce the time spent online. Many of those who’ve struggled to balance internet use with other activities recommend such simple “digital detox” measures as leaving devices in the kitchen or any other room but the bedroom at night. Cognitive behavioral therapy can also help address addiction-like behaviors, like constant checking habits.

Amidst growing concerns about the increased amount of time people are spending online, the “digital detox” has become a popular way to cope. A digital detox involves temporarily abstaining from using devices, like computers and smartphones. Someone may go on a digital detox in order to re-engage with a passion or activity, focus more on in-person interactions, or break free of a pattern of compulsive or excessive use. Digital detoxes also allow more time for self-care that a person may have been neglecting in order to stay plugged into the internet, which can lead to lower stress levels and better sleep.

There is no one-size-fits-all answer. You may want to digitally detox if you notice that you’re experiencing sleep disruptions due to staying up late or waking up early to be on a device, if the internet is making you feel depressed, or if the constant need to be connected causes you stress. Other signs may include feeling anxious if you can’t locate your phone, having FOMO ( fear of missing out) if you’re not checking the internet or social media, struggling to focus without (or due to) constant checking behaviors, etc.

Unlike other detoxes where the goal is to abstain completely, digital detoxes are more flexible and tailored to the individual. It may not be possible due to work or personal obligations to shut your devices off entirely for long periods of time. If it’s time for a digital detox , there are some strategies you can try: Block off non-screen time during the day and/or night, set a “digital curfew” for using devices at night or on weekends, specify digital-free spaces in your home (e.g., the bedroom or dinner table), and use the additional time in fulfilling ways (e.g., socialize, rekindle old interests, volunteer, etc.).

Use the internet and social media with purpose; set time limits on your unstructured use to avoid going down long and unfulfilling rabbit holes. Take advantage of the extra free time you suddenly have. Spend more time socializing in-person and volunteer. Rekindle old interests or take up a new hobby. Go outside. Pay more attention to how you are feeling, both physically and emotionally.

Encouraging young adults to tell their stories may help heal the sense of disconnection technology and the pandemic have created.

Smartphones bridge global connections yet chip away at the essence, and the joy, of face-to-face interactions.

In a new study, teens report finding more benefits than harms online, yet they admit to feeling “happy” and “peaceful” when away from their smartphones.

Today, more teens are at peace and happier when they are detached from their devices. Here are 5 ways to help parents create a smartphone contract to manage screen time.

Personal Perspective: How the internet influences understanding mental illness.

Take charge of your unhealthy smartphone use.

"Infinite" video games are designed to keep you hooked. Switching to "finite" games could help you find balance in your life.

One of these addiction game-changers could save a loved one’s life. Or your own.

Most parenting blogs recommend setting a two-hour-per-day time limit on all screens for minors. Is that what's best for your children?

While our phones provide us with many benefits, it's essential to maintain a balanced relationship with them.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Know If You Have an Internet Addiction and What to Do About It

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/ElizabethHartneyPhD_1000-cdd9def4f706402cad18d66303e23ede.jpg)

Emily is a board-certified science editor who has worked with top digital publishing brands like Voices for Biodiversity, Study.com, GoodTherapy, Vox, and Verywell.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Emily-Swaim-1000-0f3197de18f74329aeffb690a177160c.jpg)

picturegarden / Getty Images

- Top 5 Things to Know

Internet Addiction in Kids

- What to Do If You're Addicted

Internet addiction is a behavioral addiction in which a person becomes dependent on the Internet or other online devices as a maladaptive way of coping with life's stresses.

Internet addiction has and is becoming widely recognized and acknowledged. So much so that in 2020, the World Health Organization formally recognized addiction to digital technology as a worldwide problem, where excessive online activity and Internet use lead to struggles with time management, sleep, energy, and attention.

Top 5 Things to Know About Internet Addiction

- Internet addiction is not yet an officially recognized mental disorder. Researchers have formulated diagnostic criteria for Internet addiction, but it is not included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR) . However, Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) is included as a condition for further study, and Internet addiction is developing as a specialist area.

- At least three subtypes of Internet addiction have been identified: video game addiction , cybersex or online sex addiction, and online gambling addiction .

- Increasingly, addiction to mobile devices, such as cellphones and smartphones, and addiction to social networking sites, such as Facebook, are being investigated. There may be overlaps between each of these subtypes. For example, online gambling involves online games, and online games may have elements of pornography.

- Sexting , or sending sexually explicit texts, has landed many people in trouble. Some have been teens who have found themselves in hot water with child pornography charges if they are underage. It can also be a potential gateway to physical infidelity .

- Treatment for Internet addiction is available, but only a few specialized Internet addiction services exist. However, a psychologist with knowledge of addiction treatment will probably be able to help.

If you or a loved one are struggling with an addiction, contact the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) National Helpline at 1-800-662-4357 for information on support and treatment facilities in your area.

For more mental health resources, see our National Helpline Database .

As Internet addiction is not formally recognized as an addictive disorder, it may be difficult to get a diagnosis. However, several leading experts in the field of behavioral addiction have contributed to the current knowledge of symptoms of Internet addiction. All types of Internet addiction contain the following four components:

Excessive Use of the Internet

Despite the agreement that excessive Internet use is a key symptom, no one seems able to define exactly how much computer time counts as excessive. While guidelines suggest no more than two hours of screen time per day for youths under 18, there are no official recommendations for adults.

Furthermore, two hours can be unrealistic for people who use computers for work or study. Some authors add the caveat “for non-essential use,” but for someone with Internet addiction, all computer use can feel essential.

Here are some questions from Internet addiction assessment instruments that will help you to evaluate how much is too much.

How Often Do You...

- Stay online longer than you intended?

- Hear other people in your life complain about how much time you spend online?

- Say or think, “Just a few more minutes” when online?

- Try and fail to cut down on how much time you spend online?

- Hide how long you’ve been online?

If any of these situations are coming up on a daily basis, you may be addicted to the Internet.

Although originally understood to be the basis of physical dependence on alcohol or drugs, withdrawal symptoms are now being recognized in behavioral addictions, including Internet addiction.

Common Internet withdrawal symptoms include anger, tension, and depression when Internet access is not available. These symptoms may be perceived as boredom, joylessness, moodiness, nervousness, and irritability when you can’t go on the computer.

Tolerance is another hallmark of alcohol and drug addiction and seems to be applicable to Internet addiction as well. This can be understood as wanting—and from the user's point of view, needing—more and more computer-related stimulation. You might want ever-increasing amounts of time on the computer, so it gradually takes over everything you do. The quest for more is likely a predominant theme in your thought processes and planning.

Negative Repercussions

If Internet addiction caused no harm, there would be no problem. But when excessive computer use becomes addictive, something starts to suffer.

One negative effect of internet addiction is that you may not have any offline personal relationships, or the ones you do have may be neglected or suffer arguments over your Internet use.

- Online affairs can develop quickly and easily, sometimes without the person even believing online infidelity is cheating on their partner.

- You may see your grades and other achievements suffer from so much of your attention being devoted to Internet use.

- You may also have little energy for anything other than computer use—people with Internet addiction are often exhausted from staying up too late on the computer and becoming sleep deprived.

- Finances can also suffer , particularly if your addiction is for online gambling, online shopping, or cybersex.

Internet addiction is particularly concerning for kids and teens. Children lack the knowledge and awareness to properly manage their own computer use and have no idea about the potential harms that the Internet can open them up to. The majority of kids have access to a computer, and it has become commonplace for kids and teens to carry cellphones.

While this may reassure parents that they can have two-way contact with their child in an emergency, there are very real risks that this constant access to the Internet can expose them to.

- Children have become increasingly accustomed to lengthy periods of time connected to the Internet, disconnecting them from the surrounding world.

- Children who own a computer and have privileged online access have an increased risk of involvement in cyberbullying , both as a victim and as a perpetrator.

- Children who engage in problematic internet use are more likely to use their cellphone for cybersex, particularly through sexting, or access apps which could potentially increase the risk of sex addiction and online sexual harms, such as Tinder.

In addition, kids who play games online often face peer pressure to play for extended periods of time in order to support the group they are playing with or to keep their skills sharp. This lack of boundaries can make kids vulnerable to developing video game addiction. This can also be disruptive to the development of healthy social relationships and can lead to isolation and victimization.

Children and teens are advised to have no more than two hours of screen time per day.

What to Do If You Have an Internet Addiction

If you recognize the symptoms of Internet addiction in yourself or someone in your care, talk to your doctor about getting help. As well as being able to provide referrals to Internet addiction clinics, psychologists, and other therapists, your doctor can prescribe medications or therapy to treat an underlying problem if you have one, such as depression or social anxiety disorder.

Internet addiction can also overlap with other behavioral addictions, such as work addiction, television addiction , and smartphone addiction.

Internet addiction can have devastating effects on individuals, families, and particularly growing children and teens. Getting help may be challenging but can make a huge difference in your quality of life.

Dresp-Langley B, Hutt A. Digital addiction and sleep . IJERPH . 2022;19(11):6910. doi:10.3390/ijerph19116910

American Psychiatric Association. Internet Gaming .

Young KS, de Abreu CN. Internet Addiction: A Handbook and Guide to Evaluation and Treatment . New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc.; 2011.

Holoyda B, Landess J, Sorrentino R, Friedman SH. Trouble at teens' fingertips: Youth sexting and the law . Behav Sci Law . 2018;36(2):170-181. doi:10.1002/bsl.2335

Jorgenson AG, Hsiao RC, Yen CF. Internet Addiction and Other Behavioral Addictions . Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am . 2016;25(3):509-520. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2016.03.004

Reid Chassiakos YL, Radesky J, Christakis D, Moreno MA, Cross C. Children and Adolescents and Digital Media . Pediatrics . 2016;138(5):e20162593. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-2593

Musetti A, Cattivelli R, Giacobbi M, et al. Challenges in Internet Addiction Disorder: Is a Diagnosis Feasible or Not ? Front Psychol . 2016;7:842. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00842

Walrave M, Heirman W. Cyberbullying: Predicting Victimisation and Perpetration . Child Soc . 2011;25:59-72. doi:10.1111/j.1099-0860.2009.00260.x

Gámez-Guadix M, De Santisteban P. "Sex Pics?": Longitudinal Predictors of Sexting Among Adolescents . J Adolesc Health. 2018;63(5):608-614. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.05.032

Hilgard J, Engelhardt CR, Bartholow BD. Individual differences in motives, preferences, and pathology in video games: the gaming attitudes, motives, and experiences scales (GAMES) . Front Psychol. 2013;4:608. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00608

Alavi SS, Ferdosi M, Jannatifard F, Eslami M, Alaghemandan H, Setare M. Behavioral Addiction versus Substance Addiction: Correspondence of Psychiatric and Psychological Views . Int J Prev Med . 2012;3(4):290-294.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2013.

By Elizabeth Hartney, BSc, MSc, MA, PhD Elizabeth Hartney, BSc, MSc, MA, PhD is a psychologist, professor, and Director of the Centre for Health Leadership and Research at Royal Roads University, Canada.

Advertisement

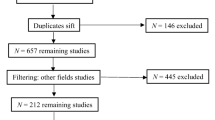

Current Research and Viewpoints on Internet Addiction in Adolescents

- Adolescent Medicine (M Goldstein, Section Editor)

- Published: 09 January 2021

- Volume 9 , pages 1–10, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- David S. Bickham ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2139-6804 1

18k Accesses

39 Citations

71 Altmetric

11 Mentions

Explore all metrics

Purpose of Review

This review describes recent research findings and contemporary viewpoints regarding internet addiction in adolescents including its nomenclature, prevalence, potential determinants, comorbid disorders, and treatment.

Recent Findings

Prevalence studies show findings that are disparate by location and vary widely by definitions being used. Impulsivity, aggression, and neuroticism potentially predispose youth to internet addiction. Cognitive behavioral therapy and medications that treat commonly co-occurring mental health problems including depression and ADHD hold considerable clinical promise for internet addiction.

The inclusion of internet gaming disorder in the DSM-5 and the ICD-11 has prompted considerable work demonstrating the validity of these diagnostic approaches. However, there is also a movement for a conceptualization of the disorder that captures a broader range of media-use behaviors beyond only gaming. Efforts to resolve these approaches are necessary in order to standardize definitions and clinical approaches. Future work should focus on clinical investigations of treatments, especially in the USA, and longitudinal studies of the disorder’s etiology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Social Media and Youth Mental Health

Paul E. Weigle & Reem M. A. Shafi

The positive aspects of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a qualitative investigation of successful adults with ADHD

Jane Ann Sedgwick, Andrew Merwood & Philip Asherson

Online Dating and Problematic Use: A Systematic Review

Gabriel Bonilla-Zorita, Mark D. Griffiths & Daria J. Kuss

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Every day we carry with us a tool that provides unlimited social, creative, and entertainment possibilities. Activities facilitated by our smartphones have always been central to the developmental goals of adolescents—as young people move toward their peers as their primary social support system, their phones provide constant connection to their friends as well as access to the popular media that often defines and shapes youth culture. Considering young people’s continued use of more venerable forms of entertainment screen media (e.g., television, video games, computers), it is not surprising that adolescents spend more time using media than they do sleeping or in school—an average of 7 h 22 min a day [ 1 ]. While the majority of young media users adequately integrate it into their otherwise rich lives, an undeniable subset suffers from what has been termed by some as internet addiction [ 2 ] but, as discussed below, has been referred to by many different names. While overuse of technology and its impact has been of concern since the days of television, the constantly changing media landscape as well as advances in our understanding of the issue requires regular updates of what is known. The purpose of this review is to provide an understanding of this issue grounded in the established evidence of the field but primarily informed by work published between 2015 and 2020 and, in doing so, address the following questions: What is internet addiction and is this the best term for the problem? What is its prevalence among adolescents around the world? What individual characteristics predispose young people to internet addiction and what are the common comorbidities? And, finally, what treatment strategies are being use and which have been found to be effective?

Defining the Issue

To answer any of these questions, first we must define the problem at hand. Unfortunately, this is a difficult task as recent publications use a wide variety of terms to reference this problem. Video game addiction, problematic internet use, problematic internet gaming, internet addiction, problematic video gaming, and numerous other terms have been used to identify this problem in the last 5 years. Such terms all have limitations. Focusing on a specific behavior, such as internet gaming, does not capture the variety of media use problems experienced by young people. Even the term “internet” may not be especially precise or consistent in meaning as online functionality is now seamless and permeates all activities on a phone, computer, tablet, game system, or television. In order to focus the nomenclature on the variety of behaviors that cross devices and avoid the term addiction which may unnecessarily stigmatize game players and impede their seeking help, my colleagues and I have suggested the use of the term problematic interactive media use (PIMU) [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ]. The term PIMU attempts to capture the broad spectrum of potential media use behaviors seen in clinical settings including gaming, information seeking, pornography use, and social media use without naming a specific behavior or type of media which could position the term for obsolescence [ 3 •].

A Focus on Gaming

Another approach to defining this issue has been to focus on internet games as they are seen as having unique features and elevated harm through excessive use [ 7 ]. In 2013 the American Psychiatric Association described internet gaming disorder (IGD) in its updated Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) as a condition needing further research in order to classify as a unique mental disorder [ 8 ]. The proposed clinical diagnosis of IGD includes persistent use of the internet to play games with associated distress or life impairment as well as endorsement of at least 5 of 9 symptoms including preoccupation with games, increased need to spend more time gaming, inability to reduce game time, lying to others about the amount of gaming, and using gaming to reduce negative mood [ 8 ]. Following suit, the World Health Organization included gaming disorder (GD) in its 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) [ 9 ]. These two diagnostic approaches both characterize problematic gaming as repetitive, persistent, lasting at least a year, and resulting in significant impairments of daily life [ 10 ]. While there is considerable overlap in the identified clinical symptoms (e.g., loss of control over gaming and continued use of gaming even when after negative consequences), the GD diagnosis does seem to focus on more severe levels of problematic use and worse functional impairment [ 10 ]. The inclusion of IGD and GD in these major diagnostic manuals have been seen as an opportunity for unification in the field around the conceptualization, and measurement of problematic gaming and resulting discussions have, to some extent, indicated increasing agreement [ 7 ].

However, in the years following the definition of IGD, numerous authors took umbrage with these diagnostic criteria pointing out limitations of the defined symptoms and calling into question the idea that there is consensus in the field around this diagnosis [ 11 ••]. For example, preoccupation with gaming, they argue, could represent a form of engagement similar to other types of engrossing activities rather than something pathological [ 11 ••]. Similarly, using gaming to avoid adverse moods is unlikely to differentiate problematic from casual gamers. The use of the term “internet” in the name of the condition was also met with resistance considering that it assumes that video games accessed through the internet are different from other video games in terms of their addictive qualities [ 11 ••]. Some argue that the field is lacking the unified definitions and extensive, foundational research necessary that must precede a diagnosis [ 12 ]. Finally, by focusing on gaming, IGD does not account for other potentially addictive online behaviors. There appears, however, not to be an easy solution to this concern. A broader conceptualization of the disorder has been seen as too general by some, but it seems untenable to create new diagnostic criteria for each specific online behavior. This complexity is evident even within the APA’s description of IGD when the manual states that “Internet gaming disorder” is “also commonly referred to as Internet use disorder, Internet addiction, or gaming addiction [ 8 ].”

Scales and Assessment

Building effective igd scales.

As evidence that much of the field is accepting IGD as a unifying conceptualization of problematic media use, numerous clinicians and scientist have investigated the DSM-5 criteria by designing and testing new scales or applying existing scales to this new framework. Some early testing utilized an interview procedure to confirm a 5-symptom cutoff for IGD, although a cutoff of 4 was adequate for differentiating between those suffering from IGD and healthy controls [ 13 ]. Scales such as the Internet Gaming Disorder Scale and its short form as well as the Internet Gaming Disorder Test (IGDT-10) have been designed and tested demonstrating that fairly short (e.g., 9 or 10 items) assessments can demonstrate strong psychometric properties, support the defined cutoff of 5 symptoms, and successfully measure a single construct [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ]. Testing has been done on other assessment tools that are aligned with the IGD criteria including the Clinical Video Game Addiction Test which provided further support for the 5-item cutoff diagnosis [ 18 ] and the Chen Internet Addiction Scale—Gaming Version which identified its own cutoff [ 19 ]. This abundance of screeners and other instruments demonstrates how, as a result of the inclusion of IGD in the DSM-5, researchers and clinicians have access to numerous well-designed and tested assessments for problematic game play. On the other hand, the profusion of scales may also indicate that the field is still far from one regularly stated goal: a universal and standardized measurement tool.

Internet Addiction Scales

To further expand the assessment landscape, researchers and clinicians who prefer a broader conceptualization of this disorder, one more aligned with internet addiction rather than gaming disorder, have also created scales for research and clinical settings. The Chen Internet Addiction Scale is one of the earliest and most utilized scales [ 20 ]. Developed by applying established concepts from substance abuse and impulse control, it and its revised form have established internal reliability and criterion validity [ 21 ]. The designers of the 20-item Internet Addiction Test (IAT) used the criteria for pathological gambling as the basis of the test and designed it specifically to differentiate between casual and compulsive internet users [ 2 ]. The IAT has high internal reliability [ 22 ], a consistent factor structure across age categories [ 23 ], and is associated with expected comorbidities including depression [ 22 ] and attention-deficit disorders [ 24 ]. The 18-item Problematic and Risky Internet Use Screening Scale (PRIUSS) has three subscales—social consequences, emotional consequences, and risky/impulsive internet use—and a 3-item version was created that used one question from each subscale [ 25 , 26 ]. The strong psychometric properties of both versions of this scale are indicative of their value as tools for identifying adolescents and young adults struggling with their technology use.

Much like the measures of IGD, these internet addiction scales are more similar than dissimilar. They all assess a diverse array of experiences and consequences related to PIMU including its impact on social relationships, sleep, and aspects of mental health. In fact, some items from the different scales are almost identical. For example, the IAT asks, “Do you choose to spend more time online over going out with others?” the PRIUSS asks, “Do you choose to socialize online instead of in person?” and the CIAS asks how much this statement matches your experiences: “I find myself going online instead of spending time with friends.” The scales share an overall approach of asking about internet use in general rather than about specific online activities. While this allows the instruments to focus on the impulsive and risky aspects of internet use in general, it requires young people to differentiate between online and offline activities, a distinction that may no longer be relevant. Scales using this approach should continually be tested and revised as technology develops.

Considering the similarities of the scales, a researcher or clinician would likely be well served by any of them. However, even though the IAT and the CIAS both have identified diagnostic cutoffs, the availability of a 3-item pre-screener for the PRIUSS makes this instrument especially useful for inclusion in a battery of in-office measures. The PRIUSS does, however, require the adolescent or young adult patient to endorse behaviors that are worded in such a way that might activate feelings of judgment or reactance. For example, the question “Do you neglect your responsibilities because of the internet?” puts the onus directly on the user with little room for rationalizing an external cause. That said, the consistently high performance of this scale indicates the set of questions as a whole are successful at classifying problematic internet users.

Because the field lacks standardized language, reporting on the current prevalence of this issue requires the use of work that employs different definitions. However, the similarities across measures likely result in reasonably comparable prevalence rates. In a systematic review focusing on problematic gaming, reported rates varied from 0.6 (in Norway) to 50% (in Korea) with a median prevalence rate of 5.5% across all included studies and 2.0% for population-based studies [ 27 ]. A meta-analyses using data across multiple decades found a pooled prevalence of 4.6% with a range of .6 to 19.9% with higher frequencies in studies performed in the 1990s (12.1%), those with samples under 1000 (8.6%), those that utilized concepts based of psychological gambling (9.5%), and those performed in Asia (9.9%) and North America (9.4%) [ 28 ••].

Recent studies reinforce the variability of prevalence in different regions of the world. In a study of 7 European countries with a representative sample of 12,938, the prevalence of IGD was 1.6% with 5.1% being considered “at-risk” for IGD with little variation among countries [ 29 ]. In studies of individual countries, prevalence of IGD in Germany ranged from 1.16 [ 30 ] to 3.5% [ 31 ]. In Italy, 12.1% were classified as having problematic use and .4% as having internet addiction [ 32 ].

Countries in Asia showed similar disparities. In a review of 38 studies from countries defined by the authors as Southeast Asia (with most being from India), prevalence of internet addiction ranged from 0 to 47.4% [ 33 ]. Among middle and high school students in Japan, prevalence was 7.9% for problematic internet use and 15.9% for adaptive internet use, a lower cutoff of the diagnostic questionnaire [ 34 ]. In rural Thailand, 5.4% reached the cutoff for IGD [ 35 ], and in Taiwan 3.1% met that threshold [ 17 ]. Among 2666 urban middle school children in China, prevalence of IGD was 13.0% [ 36 ]. Finally, in rural South Korea, the prevalence of PIU was 21.6% among a sample of 1168 13- to 18-year-olds [ 37 ].

With such disparate findings from around the world, it seems that PIMU prevalence varies considerably from county to country and region to region. While this may be the case, summary findings from two large reviews do have similar final estimates—5.5% [ 27 ] and 4.6% [ 28 •• ]. This rate is also similar to the prevalence of youth “at-risk” for IGD across Europe (5.1%) [ 29 ] and for full IGD in rural Thailand (5.4%) [ 35 ]. While far from definitive, 5% might be our strongest general prevalence estimate given the evidence. There are some sample and study characteristics that seem to result in a higher prevalence. Unsurprisingly, rates are higher when less restrictive definitions of the disorder are used. There is also some evidence that rates are lower in Europe and higher in North America and Asia, but these results were not universal. If we accept a prevalence of approximately 5% in the USA, that would translate to approximately 1.5 million adolescents experiencing significant life consequences as a result of their struggles with digital technology. Understanding who is most at risk and how best to treat this problem is essential for comprehensive, contemporary adolescent medicine.

Potential Determinants of PIMU

Individual characteristics, demographic features, and psychosocial traits have all been identified as possible determinants of PIMU. Perhaps the most widely documented risk factor is being male. Prevalence among boys and young men has been found to be 2 [ 38 ], 3 [ 28 ••], or even 5 [ 27 ] times higher than among girls and young women. Throughout early adolescence PIMU increases with age, but peaks around 15–16 [ 39 ]. Indicators of lower socioeconomic status including less maternal education and a single parent household have been shown to increase the risk for PIMU [ 36 ].

Family Functioning

Young people’s family functioning also seems to play a role in their development of PIMU. Risk factors seem to include lower levels of family cohesion, more family conflict, and poorer family relationships [ 40 ]. The most frequent finding in a recent systematic review was that a worse parent-child relationship was associated with more problematic gaming [ 41 ]. Less time with parents, less affection from parents, more hostility from parents, and lower quality parenting were all family characteristics potentially indicated in the development of gaming problems [ 41 ]. Game play and other online social activities may serve as solace from difficult family lives as adolescents seeking treatment for gaming addiction report that they are motived to play in part by escapism and the draw of virtual friendships [ 42 ]. At the other end of the spectrum, positive parent-child relationships may be protective against the development of problematic gaming [ 41 ]. Additionally, parental monitoring of adolescents’ internet use can also reduce PIMU which, in turn, improves parent-child relationships [ 43 ]. Parents, it seems, have some prevention tools available to them which could improve their family functioning overall. Fathers appear to have a particularly influential role as their relationships with adolescents has been shown to be especially protective [ 41 , 43 ].

Personality Traits

Certain individual personality traits appear to be common among adolescents with media use issues potentially indicating that young people with these traits are predisposed to develop PIMU. PIMU sufferers regularly demonstrate limitations in areas related to self-control including higher levels of impulsivity. In two studies examining problematic smartphone use, one identified dysfunctional impulsivity and low self-control as two key risk factors [ 44 ] and the other found impulsivity to predict this behavior in their female participants [ 45 ]. Patients diagnosed with IGD also demonstrated higher levels of impulsivity than healthy controls [ 46 ]. A systematic review of research examining the personality traits predictive of IGD concludes that impulsivity plays a role in IGD and that certain aspects of this trait, such as high levels of urgency, are especially potent risk factors. [ 47 •].

In addition to impulsivity, behavior traits related to aggression and hostility are common among adolescents with media use problems. Aggressive tendencies were identified as a predictor of IGD by multiple studies in a recent review of the research [ 47 •]. In a large European survey study, adolescents who reported IGD had higher scores on rule-breaking and aggressive behaviors scales [ 29 ]. While it may seem that aggression findings are simply indicative of the observed gender differences, models that include gender as well as other traits that predict PIMU found that hostility was independently associated with problematic smartphone use [ 48 ] and conduct problems were predictive of problematic internet use [ 49 ].

Neuroticism, the tendency to feel nervous and to worry, has been identified as a potential predisposing factor for PIMU. Using the Big Five model of personality to investigate commonalities among young people with IGD, the authors of a recent review highlighted multiple studies linking neuroticism with PIMU and concluded that this work demonstrates a clear and consistent link [ 47 •]. Some of the strongest evidence comes from clinical samples in which young people seeking care for IGD showed higher levels of neuroticism than healthy controls [ 50 ]. Additionally, neuroticism may be an important trait that differentiates game players who have problematic use versus those who are simply heavily engaged with the games [ 51 ] perhaps in part because the control provided by video games is especially appealing to those with neurotic tendencies [ 50 ]. Neuroticism is a common element of internalizing mood disorders including anxiety and depression [ 52 ], which, as described below, are frequently comorbid with PIMU.

While it is clear that some traits are common among PIMU sufferers (and there are others not covered above), we must stop short of claiming a defining personality profile. Young people experiencing PIMU are likely to have as much diversity as they do similarity in their psychological and personality characteristics. Some of the most conclusive findings originate from clinical samples, but, because of limited specialized care opportunities, this work has been almost entirely conducted outside of the USA. Seeing as culture plays an important role in the development of personality, investigations are necessary to determine if our current knowledge is generalizable to the USA.

Neurobiology and Brain Function

Apart from individual characteristics and family functioning, there appear to be some neurobiological dysfunction that may characterize PIMU sufferers. Working from models based on the brain functioning in gambling and substance use addicts, researchers have looked for similarities with these disorders. Sussman and colleagues call attention to the viewpoint that people are not actually addicted to a substance or a behavior itself but rather to the brain’s response to the drug or activity [ 53 ••]. This perspective opens the door for digital entertainment obsession to be compared to substance use and gambling disorder. Video games and certain types of internet use have been shown to release dopamine at a rapid rate leading to immediate gratification and the potential for a repetitive response that can include compulsive behaviors and increased tolerance [ 53 ••]. In a simultaneous test of reward processing and inhibitory control, both behavioral and electroencephalography findings indicate adolescents with IGD demonstrate irregularities in both systems [ 54 • ]. Additionally, fMRI studies have documented neurobiological explanations for dysregulated reward processing, diminished impulse control, and other behavioral and cognitive patterns in IGD sufferers that are similar to those from people with gambling disorders [ 55 ]. Imaging studies have demonstrated that the brains of adolescents with internet addiction share at least one structural abnormality with brains of those with substance use disorder, namely, reduced thickness in the orbitofrontal cortex [ 56 ]. The evidence at hand seems to indicate that PIMU shares similarities in neural functioning and potentially some brain structures with other compulsive behaviors as well as substance use. However, there are still many fewer neuroimaging studies of PIMU sufferers than of substance users, and many of the existing studies are hindered by small, heterogeneous samples and lack of attention to comorbid conditions [ 55 ].

The observed similarities between PIMU and substance use disorder do not necessarily signify that compulsive technology use should be characterized as a behavioral addiction. In fact, there are strong reasons to consider other conceptualizations for this set of behaviors. Excessive use may be indicative of maladaptive coping [ 57 ] or the manifestation of existing self-regulatory problems [ 58 •]. Rather than being a novel disorder, PIMU behaviors may be symptoms of existing psychiatric problems being expressed within the digital environment [ 3 •]. If these underlying disorders are appropriate explanations for these behaviors, then, some argue, we should not classify the set of symptoms as a behavioral addiction [ 59 ]. Furthermore, there is limited evidence that stopping use results in serious withdrawal symptoms which is a key factor in some diagnostic tools [ 60 ].The term addiction may also convey a sense of stigma and potentially interfere with one’s likelihood for seeking help or leading to incorrect treatment [ 3 , 61 ]. A consistent set of observed, troublesome, comorbid disorders may support the possibility that existing problems drive problematic media use rather than the behavior indicating a uniquely diagnosable behavioral addiction.

Comorbidities

A core set of mental health problems comorbid with PIMU have been identified and include depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety, and autism [ 62 •]. As most of the research in this area is cross-sectional, the exact explanation for the association between PIMU and these other disorders is unknown and could include a one directional relationship (in either direction), a bi-directional relationship, or a common factor causing both issues [ 62 •]. Bearing in mind the complex etiology of these severe mental health issues, PIMU may very well arise from pre-existing mental health problems. The behaviors and environment afforded by excessive game play and internet use may also exacerbate certain symptoms of these disorders. The associations likely differ by unique co-occurring disorder as well as by the specific behaviors evident in an individual’s experience of PIMU. Longitudinal representative research along with additional clinical investigations examining different presentations of PIMU (especially using samples from the USA) is needed to fully understand this relationship.

Depression and Anxiety

Regardless of the specifics of the relationships, identifying the most common mental health issues that are comorbid with PIMU can help illuminate the disorder. Depression is consistently found to be predictive of problematic video game, internet, and smartphone use [ 63 , 64 , 65 ]. In a study comparing multiple predictors of the Internet Addiction Scale, level of depression had the strongest association even when considering demographics, personality traits, and future time perspective (i.e., the ability to envision and pursue future goals) [ 22 ]. Considering anxiety is closely related to depression, it is not surprising that it too has been shown to be linked to PIMU. Young people’s use of technology to cope with depression and anxiety likely explains at least some of these observed relationships, but a reciprocal relationship between PIMU and depression or anxiety is likely most realistic [ 64 , 66 ].

Seeing as impulsivity is a common trait of adolescents suffering from PIMU, it follows that ADHD is one of its most common comorbidities. In a recent review, 87% of the included studies found significant relationships between ADHD symptoms and PIMU [ 62 •]. Findings from a meta-analysis align with these results with studies consistently showing that PIMU is present at higher rates among those with ADHD from those without [ 67 ]. Furthermore, adolescents with ADHD show more severe symptoms of PIMU and are less likely to respond to treatment [ 67 , 68 ]. Ease of boredom, poor self-control, and other typical symptoms of ADHD are likely driving this association [ 67 ].

PIMU was shown to be prevalence in 45.5% of a small clinical sample of youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) [ 69 ]. Youth with ASD have higher levels of compulsive internet use and video game play compared to healthy peers [ 70 ]. Online communication platforms especially those that occur within the well-defined ruleset of multiplayer games may be seen as less threatening and thereby particularly attractive to youth with ASD who desire connection but tend to lack well-developed social skills [ 4 ]. The coexistence of ADHD and ASD is an especially predictive combination with PIMU observed in 12.5% of patients with ADHD, 10.8% of those with ASD, and 20.0% of those with both disorders [ 71 ].

For clinicians hoping to better discriminate between adolescents who are heavily engaged with screen media and those who are experiencing problematic use, it is likely effective to attend carefully to young people with mental health issues commonly comorbid to PIMU. To inform on this effort, my colleagues and I have proposed the acronym A-SAD (ADHD, social anxiety, ASD,depression) to remember these key disorders [ 5 •]. While this suggestion is consistent with current evidence, research testing this approach is still necessary in order to understand its overall effectiveness in clinical settings.

Even though there is continued debate about the nomenclature around this issue and the appropriateness of labeling the problem an addiction or its own mental health diagnosis, adolescents around the world are seeking treatment to overcome their disordered media use and its consequences. As of yet, there is not an agreed upon approach for treating PIMU resulting in resourceful and skilled clinicians applying and adapting multiple approaches known to be effective to similar issues to this newer problem. For many years, there were few systematic investigations of these treatments, but recently the number of clinical trials has increased.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

With rigorous research in this field becoming more common, a recent review was able to rely more heavily on randomized clinical trials in reaching its conclusions [ 72 •]. This work identified 3 treatment possibilities as most heavily researched—cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), pharmacological, and group/family therapies—however, approaches in all three were only classified as experimental [ 72 •]. CBT seeks to change problematic thought patterns and their resulting behaviors especially in terms of coping with psychological problems in healthy, direct ways. The approach of using CBT to address the cognitions of problematic users was proposed almost two decades ago and has been applied and adjusted to numerous populations and settings [ 73 ]. In a prototypical study, patients identified as having internet addiction and a comorbid disorder received CBT for 10 sessions and showed improvement in both internet use and anxiety [ 74 •]. Pooled effect sizes from studies of this treatment have demonstrated that overall, CBT is successful at reducing symptoms of depression and of IGD and slightly less so for anxiety [ 75 ••]. Although there is less evidence for CBT’s effectiveness at reducing game play, such a goal is less central as gaming is not inherently problematic [ 75 ••]. Dialectical behavior therapy, which is based on CBT but addresses emotions along with thoughts and behaviors, has also been applied to PIMU and seems to offer promise for future treatment [ 6 ].

Pharmacological Treatment

Other treatments including pharmacological and group and family therapies have not been the subject of as many research investigations as CBT, but findings from these areas do show encouraging effects. The general approach of pharmacological treatment has been to use medications to treat comorbid conditions or underlying pathologies of PIMU including depression [ 76 ], ADHD [ 77 ], obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) [ 78 ], and others. In an exemplar RCT of 114 adolescents and adults with IGD, the effectiveness of two antidepressants (escitalopram and bupropion) were investigated [ 79 ••]. Both were effective at reducing IGD, but bupropion also improved impulsivity, inattention, and mood problems which is consistent with its reported use as a treatment for ADHD [ 79 ••]. Following a similar protocol, researchers compared the effectiveness of two ADHD medications, a stimulant (methylphenidate) and non-stimulant (atomoxetine), on symptoms of both ADHD and IGD [ 80 ]. Both medications successfully reduced symptoms of IGD seemingly through their ability to regulate impulsivity [ 80 ]. Other studies reveal similar effects resulting in an overall conclusion that a pharmacological approach can be successful in reducing symptoms of both PIMU and comorbid disorders [ 81 ].

Group and Family Therapies

Group and family therapies are also being used to address PIMU. While group-based interventions that are 8-weeks or longer and include 9–12 people appear most effective [ 82 ], these approaches vary greatly making it difficult to determine which other aspects of the approach contribute to any observed successes. A systematic review describes four studies using single-family groups, multi-family groups, and school-based groups and implementing CBT-based approaches, novel psychotherapy approaches designed specifically for PIMU sufferers, and traditional family therapy approaches [ 81 ]. Group interventions have also been designed to prevent PIMU among adolescents although the effectiveness of this approach is still unknown [ 83 ]. Investigations of these treatments do show some promise. For example, a study of using multi-family group therapy found 20 out of 21 adolescent participants were no longer considered addicted to the internet following the six, 2-h sessions [ 84 ]. While the approach as a whole is based on strategies known to be effective in substance use and other adolescent problems, the heterogeneity of the therapies makes it difficult to draw any final conclusions.

There has been much advancement in identifying and treating PIMU over the last 5 years. The inclusion of IGD in the DSM-5 and of GD in the WHO’s ICD-11 has been the impetus for a growing consensus around terminology and approach. Considerable research has demonstrated that IGD can be assessed reliably and that the defined cutoffs effectively differentiate between those with and without the disorder. However, a large debate continues about whether the terminology and subsequent conceptual and clinical approaches should be based on a specific activity or broader set of behaviors. A framework that describes and addresses a multitude of behaviors that share certain determinants, comorbidities, and expressions can avoid the unsustainable situation of developing a new term and tactic for every problematic media behavior.

Additional research is necessary to more fully develop our clinical understanding and treatment approach to PIMU. Foundational, longitudinal work would help disentangle the direction of association between mental health problems and PIMU, and clinical investigations could continue to determine how therapy and medication can most effectively treat the condition. Clinical work investigating patient samples from the USA are very rare and are necessary to build awareness and increase resources available to treat the problem. Additionally, new research should explore the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on PIMU. As screens have been relied upon for essential purposes including education, communication, and social connectedness, use has inevitably risen, and youth previously balancing media use and other activities may find themselves struggling. While our knowledge has grown substantially in this area, there are still questions that need to be answered before we can effectively treat this modern facet of adolescent health.

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Rideout VJ, Robb MB. The common sense census: media use by tweens and teens. San Francisco, CA: Common Sense Media; 2019.

Google Scholar

Young KS. Internet addiction: the emergence of a new clinical disorder. CyberPsychology Behav. 1998;1:237–44.

Article Google Scholar

Rich M, Tsappis M, Kavanaugh JR. Problematic interactive media use among children and adolescents: addiction, compulsion, or syndrome? In: Internet addiction in children and adolescents: risk factors, assessment, and treatment. New York, NY, US: Springer Publishing Company; 2017. page 3–28. The chapter in which the term Problematic Interactive Media Use (PIMU) is presented .

Pluhar E, Kavanaugh JR, Levinson JA, Rich M. Problematic interactive media use in teens: comorbidities, assessment, and treatment. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2019;12:447–55.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Nereim C, Bickham D, Rich M. A primary care pediatrician’s guide to assessing problematic interactive media use. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2019;31. A summary specifically for clinicians in which the acronym A-SAD is presented as a tool for recalling mental health problems that frequently co-occur with PIMU .

Pluhar E, Jhe G, Tsappis M, Bickham D, Rich M. Adapting dialectical behavior therapy for treating problematic interactive media use. J Psychiatr Pr. 2020;26:63–70.

Petry NM, Rehbein F, Gentile DA, Lemmens JS, Rumpf H-J, Mößle T, et al. An international consensus for assessing internet gaming disorder using the new DSM-5 approach. Addiction. 2014;109:1399–406.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Book Google Scholar

World Health Organization. International classification of diseases for mortality and morbidity statistics. 11th ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2018.

Jo YS, Bhang SY, Choi JS, Lee HK, Lee SY, Kweon Y-S. Clinical characteristics of diagnosis for internet gaming disorder: comparison of DSM-5 IGD and ICD-11 GD diagnosis. J Clin Med. 2019;8.

Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD, Pontes HM. Chaos and confusion in DSM-5 diagnosis of Internet Gaming Disorder: Issues, concerns, and recommendations for clarity in the field. J Behav Addict 2017;6:103–9. A key piece critiquing the diagnostic criteria included for Internet Gaming Disorder in the DSM-5.

Van Rooij AJ, Kardefelt-Winther D. Lost in the chaos: flawed literature should not generate new disorders. J Behav Addict. 2017;6:128–32.

Ko C-H, Yen C-F, Yen C-N, Yen J-Y, Chen C-C, Chen S-H. Screening for internet addiction: an empirical study on cut-off points for the Chen internet addiction scale. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2005;21:545–51.

Lemmens JS, Valkenburg PM, Gentile DA. The internet gaming disorder scale. Psychol Assess. 2015;27:567–82.

Pontes HM, Griffiths MD. Measuring DSM-5 internet gaming disorder: development and validation of a short psychometric scale. Comput Human Behav. 2015;45:137–43.

Kiraly O, Sleczka P, Pontes HM, Urban R, Griffiths MD, Demetrovics Z. Validation of the ten-item internet gaming disorder test (IGDT-10) and evaluation of the nine DSM-5 internet gaming disorder criteria. Addict Behav. 2017;64:253–60.

Chiu YC, Pan YC, Lin YH. Chinese adaptation of the ten-item internet gaming disorder test and prevalence estimate of internet gaming disorder among adolescents in Taiwan. J Behav Addict. 2018;7:719–26.

van Rooij AJ, Schoenmakers TM, Van de Mheen D. Clinical validation of the C-VAT 2.0 assessment tool for gaming disorder: a sensitivity analysis of the proposed DSM-5 criteria and the clinical characteristics of young patients with “video game addiction.” Addict Behav 2017;64:269–274

Ko CH, Chen SH, Wang CH, Tsai WX, Yen JY. The clinical utility of the Chen Internet Addiction Scale-Gaming Version, for internet gaming disorder in the DSM-5 among young adults. Int J Env. Res Public Heal. 2019;16.

Chen S-H, Weng L-J, Su Y-J, Wu H-M, Yang P-F. Development of a Chinese internet addiction scale and its psychometric study. Chinese J Psychol. 2003;45:279–94.

Mak K-K, Lai C-M, Ko C-H, Chou C, Kim D-I, Watanabe H, et al. Psychometric properties of the revised Chen Internet Addiction Scale (CIAS-R) in Chinese adolescents. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2014;42:1237–45.

Przepiorka A, Blachnio A, Cudo A. The role of depression, personality, and future time perspective in internet addiction in adolescents and emerging adults. Psychiatry Res. 2019;272:340–8.

Chin F, Leung CH. The concurrent validity of the internet addiction test (IAT) and the mobile phone dependence questionnaire (MPDQ). PLoS One2018;13.

Tateno M, Teo AR, Shirasaka T, Tayama M, Watabe M, Kato TA. Internet addiction and self-evaluated attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder traits among Japanese college students. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;70:567–72.

Jelenchick LA, Eickhoff J, Christakis DA, Brown RL, Zhang C, Benson M, et al. The Problematic and Risky Internet Use Screening Scale (PRIUSS) for adolescents and young adults: scale development and refinement. Comput. Human Behav. 2014;35: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.01.035 .

Moreno MA, Arseniev-Koehler A, Selkie E. Development and testing of a 3-item screening tool for problematic internet use. J. Pediatr. 2016;176:167–172.e1.

Paulus FW, Ohmann S, von Gontard A, Popow C. Internet gaming disorder in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018;60:645–59.

Fam JY. Prevalence of internet gaming disorder in adolescents: a meta-analysis across three decades. Scand J Psychol 2018;59:524–31. A comprehensive review and analysis of IGD prevelance studies conducted between 1994 and 2015 that identifies characteristics of studies that are related to higher observed prevelance.

Muller KW, Janikian M, Dreier M, Wolfling K, Beutel ME, Tzavara C, et al. Regular gaming behavior and internet gaming disorder in European adolescents: results from a cross-national representative survey of prevalence, predictors, and psychopathological correlates. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;24:565–74.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Rehbein F, Kliem S, Baier D, Mossle T, Petry NM. Prevalence of internet gaming disorder in German adolescents: diagnostic contribution of the nine DSM-5 criteria in a state-wide representative sample. Addiction. 2015;110:842–51.

Wartberg L, Kriston L, Thomasius R. Internet gaming disorder and problematic social media use in a representative sample of German adolescents: prevalence estimates, comorbid depressive symptoms and related psychosocial aspects. Comput. Human Behav. 2020;103:31–6.

Vigna-Taglianti F, Brambilla R, Priotto B, Angelino R, Cuomo G, Diecidue R. Problematic internet use among high school students: prevalence, associated factors and gender differences. Psychiatry Res. 2017;257:163–71.

Balhara YPS, Mahapatra A, Sharma P, Bhargava R. Problematic internet use among students in South-East Asia: current state of evidence. Indian J Public Heal. 2018;62:197–210.

Mihara S, Higuchi S. Cross-sectional and longitudinal epidemiological studies of internet gaming disorder: a systematic review of the literature. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2017;71:425–44.

Taechoyotin P, Tongrod P, Thaweerungruangkul T, Towattananon N, Teekapakvisit P, Aksornpusitpong C, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of internet gaming disorder among secondary school students in rural community, Thailand: a cross-sectional study BMC Res Notes 2020;13:11.

Yang X, Jiang X, Mo PK, Cai Y, Ma L, Lau JT. Prevalence and interpersonal correlates of internet gaming disorders among Chinese adolescents. Int J Env Res Public Heal. 2020;17.

Lee J-Y, Kim S-Y, Bae K-Y, Kim J-M, Shin I-S, Yoon J-S, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for problematic internet use among rural adolescents in Korea. Asia-Pacific psychiatry Off J Pacific Rim Coll Psychiatr. 2018;10:e12310.

Yang J, Guo Y, Du X, Jiang Y, Wang W, Xiao D, et al. Association between problematic internet use and sleep disturbance among adolescents: the role of the child’s sex. Int J Env. Res Public Heal. 2018;15.

Karacic S, Oreskovic S. Internet addiction through the phase of adolescence: a questionnaire study. JMIR Ment Heal. 2017;4:e11.

Bonnaire C, Phan O. Relationships between parental attitudes, family functioning and internet gaming disorder in adolescents attending school. Psychiatry Res. 2017;255:104–10.

Schneider LA, King DL, Delfabbro PH. Family factors in adolescent problematic internet gaming: a systematic review. J Behav Addict. 2017;6:321–33.

Beranuy M, Carbonell X, Griffiths MD. A qualitative analysis of online gaming addicts in treatment. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2013;11:149–61.

Su B, Yu C, Zhang W, Su Q, Zhu J, Jiang Y. Father–child longitudinal relationship: parental monitoring and internet gaming disorder in Chinese adolescents. Front Psychol. 2018;9:95.

Kim Y, Jeong JE, Cho H, Jung DJ, Kwak M, Rho MJ, et al. Personality factors predicting smartphone addiction predisposition: behavioral inhibition and activation systems, impulsivity, and self-control. PLoS One. 2016;11:15.

CAS Google Scholar

Lee SY, Lee D, Nam CR, Kim DY, Park S, Kwon JG, et al. Distinct patterns of internet and smartphone-related problems among adolescents by gender: latent class analysis. J Behav Addict. 2018;7:454–65.

Choi S-W, Kim H, Kim G-Y, Jeon Y, Park S, Lee J-Y, et al. Similarities and differences among internet gaming disorder, gambling disorder and alcohol use disorder: a focus on impulsivity and compulsivity. J Behav Addict. 2014;3:246–53.

Gervasi AM, La Marca L, Costanzo A, Pace U, Guglielmucci F, Schimmenti A. Personality and internet gaming disorder: a systematic review of recent literature. Curr. Addict. Reports 2017;4:293–307. An extensive review that uses the Big Five Model of personlity as framework for an investigation of a wide range of traits that are associated to IGD .

Firat S, Gul H, Sertcelik M, Gul A, Gurel Y, Kilic BG. The relationship between problematic smartphone use and psychiatric symptoms among adolescents who applied to psychiatry clinics. Psychiatry Res. 2018;270:97–103.

Wartberg L, Brunner R, Kriston L, Durkee T, Parzer P, Fischer-Waldschmidt G, et al. Psychopathological factors associated with problematic alcohol and problematic internet use in a sample of adolescents in Germany. Psychiatry Res. 2016;240:272–7.

Müller KW, Beutel ME, Egloff B, Wölfling K. Investigating risk factors for internet gaming disorder: a comparison of patients with addictive gaming, pathological gamblers and healthy controls regarding the big five personality traits. Eur Addict Res. 2014;20:129–36.

Lehenbauer-Baum M, Klaps A, Kovacovsky Z, Witzmann K, Zahlbruckner R, Stetina BU. Addiction and engagement: an explorative study toward classification criteria for internet gaming disorder. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2015;18:343–9.

Griffith JW, Zinbarg RE, Craske MG, Mineka S, Rose RD, Waters AM, et al. Neuroticism as a common dimension in the internalizing disorders. Psychol Med. 2010;40:1125–36.

Sussman CJ, Harper JM, Stahl JL, Weigle P. Internet and video game addictions: diagnosis, epidemiology, and neurobiology. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2018;27:307–26. A thorough review with an excellent description of the neurobiology research and an explanation of the neural processes involved with internet addiction .

Li Q, Wang Y, Yang Z, Dai W, Zheng Y, Sun Y, et al. Dysfunctional cognitive control and reward processing in adolescents with Internet gaming disorder. Psychophysiology 2020;57:e13469. In this study using behavioral and electrophysiological measures, adolescents with IGD demonstrated limits in their control and approach systems through both the go/no-go task and EEG results.

Fauth-Buhler M, Mann K. Neurobiological correlates of internet gaming disorder: similarities to pathological gambling. Addict Behav. 2017;64:349–56.

Hong SB, Kim JW, Choi EJ, Kim HH, Suh JE, Kim CD, et al. Reduced orbitofrontal cortical thickness in male adolescents with internet addiction. Behav Brain Funct. 2013;9:5.

Starcevic V. Internet gaming disorder: inadequate diagnostic criteria wrapped in a constraining conceptual model. J Behav Addict. 2017;6:110–3.

Przybylski AK, Weinstein N, Murayama K. Internet gaming disorder: investigating the clinical relevance of a new phenomenon. Am J Psychiatry 2017;174:230–6. A report on four survey studies representing a total of 18,932 participants that investigated the prevalence of IGD and found that 1% or less would be classified as suffering from this disorder.

Kardefelt-Winther D, Heeren A, Schimmenti A, van Rooij A, Maurage P, Carras M, et al. How can we conceptualize behavioural addiction without pathologizing common behaviours? Addiction. 2017;112:1709–15.

Kaptsis D, King DL, Delfabbro PH, Gradisar M. Withdrawal symptoms in internet gaming disorder: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;43:58–66.

Quandt T. Stepping back to advance: why IGD needs an intensified debate instead of a consensus. J Behav Addict. 2017;6:121–3.

Gonzalez-Bueso V, Santamaria JJ, Fernandez D, Merino L, Montero E, Ribas J. Association between internet gaming disorder or pathological video-game use and comorbid psychopathology: a comprehensive review. Int J Env. Res Public Heal. 2018;15. This extremely in-depth review examines the associations between IGD and numerous mental health disorders in 24 studies. Results showed common co-occurrence between IGD and anxiety, depression, and ADHD symptoms.

Boumosleh JM, Jaalouk D. Depression, anxiety, and smartphone addiction in university students-a cross sectional study. PLoS One 2017;12:14.

Loton D, Borkoles E, Lubman D, Polman R. Video game addiction, engagement and symptoms of stress, depression and anxiety: the mediating role of coping. Int J Ment Heal Addict. 2016;14:565–78.

Tan Y, Chen Y, Lu Y, Li L. Exploring associations between problematic internet use, depressive symptoms and sleep disturbance among southern Chinese adolescents. Int J Env. Res Public Heal. 2016;13.

Krossbakken E, Pallesen S, Mentzoni RA, King DL, Molde H, Finseras TR, et al. A cross-lagged study of developmental trajectories of video game engagement, addiction, and mental health. Front Psychol. 2018;9:2239.

Wang HR, Cho H, Kim DJ. Prevalence and correlates of comorbid depression in a nonclinical online sample with DSM-5 internet gaming disorder. J Affect Disord. 2018;226:1–5.

Han DH, Yoo M, Renshaw PF, Petry NM. A cohort study of patients seeking internet gaming disorder treatment. J Behav Addict. 2018;7:930–8.

Kawabe K, Horiuchi F, Miyama T, Jogamoto T, Aibara K, Ishii E, et al. Internet addiction and attention-deficit / hyperactivity disorder symptoms in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Res Dev Disabil. 2019;89:22–8.

MacMullin JA, Lunsky Y, Weiss JA. Plugged in: electronics use in youth and young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2015;20:45–54.

So R, Makino K, Fujiwara M, Hirota T, Ohcho K, Ikeda S, et al. The prevalence of internet addiction among a Japanese adolescent psychiatric clinic sample with autism spectrum disorder and/or attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a cross-sectional study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;47:2217–24.

Zajac K, Ginley MK, Chang R, Petry NM. Treatments for internet gaming disorder and internet addiction: a systematic review. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2017;31:979–94. A unique approach that reviews treament studies for IGD and Internet addiction separately and describes in detail their methodology, results, strengths, and limitations.

Davis RA. A cognitive-behavioral model of pathological internet use. Comput. Human Behav. 2001;17:187–95.

Santos VA, Freire R, Zugliani M, Cirillo P, Santos HH, Nardi AE, et al. Treatment of internet addiction with anxiety disorders: treatment protocol and preliminary before-after results involving pharmacotherapy and modified cognitive behavioral therapy. JMIR Res Protoc 2016;5:e46. In this clincial study, patients with internet addiction and either panic disorder or generalized anxiety disorder received medication for their anxiety and 10 sessions of modified CBT. All 39 patients showed improved anxiety and internet addiction scores reduced on average.

Stevens MWR, King DL, Dorstyn D, Delfabbro PH. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for internet gaming disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Psychother 2019;26:191–203. This analysis of 12 studies in which CBT was utilized to treat IGD found the therapy to be highly effective in reducing IGD symptoms and depression and slightly less successful at treating anxiety. Evidence from a small number of studies suggested that the effects of the therapy reduced with time .

Han DH, Renshaw PF. Bupropion in the treatment of problematic online game play in patients with major depressive disorder. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26:689–96.

Han DH, Lee YS, Na C, Ahn JY, Chung US, Daniels MA, et al. The effect of methylphenidate on internet video game play in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2009;50:251–6.

Bipeta R, Yerramilli SS, Karredla AR, Gopinath S. Diagnostic stability of internet addiction in obsessive-compulsive disorder: data from a naturalistic one-year treatment study. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2015;12:14–23.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Song J, Park JH, Han DH, Roh S, Son JH, Choi TY, et al. Comparative study of the effects of bupropion and escitalopram on Internet gaming disorder. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2016;70:527–35. In this RCT where adolescents and adults with IGD were assigned to receive either one of two anti-depressants or no medication, both drug treatments were effective but bupropion was more successful at improving IGD symptoms, attention problems, and impulsivity.

Park JH, Lee YS, Sohn JH, Han DH. Effectiveness of atomoxetine and methylphenidate for problematic online gaming in adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Hum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp. 2016;31:427–32.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Kuss DJ, Lopez-Fernandez O. Internet addiction and problematic internet use: a systematic review of clinical research. World J psychiatry. 2016;6:143–76.

Chun J, Shim H, Kim S. A meta-analysis of treatment interventions for internet addiction among Korean adolescents. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2017;20:225–31.

Lindenberg K, Halasy K, Schoenmaekers S. A randomized efficacy trial of a cognitive-behavioral group intervention to prevent internet use disorder onset in adolescents: the PROTECT study protocol. Contemp. Clin trials Commun 2017;6:64–71.

Liu Q-X, Fang X-Y, Yan N, Zhou Z-K, Yuan X-J, Lan J, et al. Multi-family group therapy for adolescent internet addiction: exploring the underlying mechanisms. Addict Behav. 2015;42:1–8.

Download references

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Jill Kavanaugh, MLIS for her assistance with the literature searches for this review.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Digital Wellness Lab, Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital, 300 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA, 02115, USA

David S. Bickham

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to David S. Bickham .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.