Race and Ethnicity

Race is a concept of human classification scheme based on visible features including eye color, skin color, the texture of the hair and other facial and bodily characteristics. Through these features, humans are ten categorized into distinct groups of population and this is enhanced by the fact that the characteristics are fully inherited.

Across the globe, debate on the topic of race has dominated for centuries. This is especially due to the resultant discrimination meted on the basis of these differences. Consequently, a lot of controversy surrounds the issue of race socially, politically but also in the scientific world.

According to many sociologists, race is more of a modern idea rather than a historical. This is based on overwhelming evidence that in ancient days physical differences mattered least. Most divisions were as a result of status, religion, language and even class.

Most controversy originates from the need to understand whether the beliefs associated with racial differences have any genetic or biological basis. Classification of races is mainly done in reference to the geographical origin of the people. The African are indigenous to the African continent: Caucasian are natives of Europe, the greater Asian represents the Mongols, Micronesians and Polynesians: Amerindian are from the American continent while the Australoid are from Australia. However, the common definition of race regroups these categories in accordance to skin color as black, white and brown. The groups described above can then fall into either of these skin color groupings (Origin of the Races, 2010, par6).

It is possible to believe that since the concept of race was a social description of genetic and biological differences then the biologists would agree with these assertions. However, this is not true due to several facts which biologists considered. First, race when defined in line with who resides in what continent is highly discontinuous as it was clear that there were different races sharing a continent. Secondly, there is continuity in genetic variations even in the socially defined race groupings.

This implies that even in people within the same race, there were distinct racial differences hence begging the question whether the socially defined race was actually a biologically unifying factor. Biologists estimate that 85% of total biological variations exist within a unitary local population. This means that the differences among a racial group such as Caucasians are much more compared to those obtained from the difference between the Caucasians and Africans (Sternberg, Elena & Kidd, 2005, p49).

In addition, biologists found out that the various races were not distinct but rather shared a single lineage as well as a single evolutionary path. Therefore there is no proven genetic value derived from the concept of race. Other scientists have declared that there is absolutely no scientific foundation linking race, intelligence and genetics.

Still, a trait such as skin color is completely independent of other traits such as eye shape, blood type, hair texture and other such differences. This means that it cannot be correct to group people using a group of features (Race the power of an illusion, 2010, par3).

What is clear to all is that all human beings in the modern day belong to the same biological sub-species referred to biologically as Homo sapiens sapiens. It has been proven that humans of different races are at least four times more biologically similar in comparison to the different types of chimpanzees which would ordinarily be seen as being looking alike.

It is clear that the original definition of race in terms of the external features of the facial formation and skin color did not capture the scientific fact which show that the genetic differences which result to these changes account to an insignificant proportion of the gene controlling the human genome.

Despite the fact that it is clear that race is not biological, it remains very real. It is still considered an important factor which gives people different levels of access to opportunities. The most visible aspect is the enormous advantages available to white people. This cuts across many sectors of human life and affects all humanity regardless of knowledge of existence.

This being the case, I find it difficult to understand the source of great social tensions across the globe based on race and ethnicity. There is enormous evidence of people being discriminated against on the basis of race. In fact countries such as the US have legislation guarding against discrimination on basis of race in different areas.

The findings define a stack reality which must be respected by all human beings. The idea of view persons of a different race as being inferior or superior is totally unfounded and goes against scientific findings.

Consequently these facts offer a source of unity for the entire humanity. Humanity should understand the need to scrap the racial boundaries not only for the sake of peace but also for fairness. Just because someone is white does not imply that he/she is closer to you than the black one. This is because it could even be true that you have more in common with the black one than the white one.

Reference List

Origin of the Races, 2010. Race Facts. Web.

Race the power of an illusion, 2010. What is race? . Web.

Sternberg, J., Elena L. & Kidd, K. 2005. Intelligence, Race, and Genetics. The American Psychological Association Vol. 60(1), 46–59 . Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, November 7). Race and Ethnicity. https://ivypanda.com/essays/race-and-ethnicity/

"Race and Ethnicity." IvyPanda , 7 Nov. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/race-and-ethnicity/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Race and Ethnicity'. 7 November.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Race and Ethnicity." November 7, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/race-and-ethnicity/.

1. IvyPanda . "Race and Ethnicity." November 7, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/race-and-ethnicity/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Race and Ethnicity." November 7, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/race-and-ethnicity/.

- Homo Sapiens, Their Features and Early Civilization

- The Rise of Anatomically Modern Homo Sapiens

- Biologically Programmed Memory

- Homo Sapiens and Large Complex of Brains

- Is homosexuality an Innate or an Acquired Trait?

- Family History Project

- Key Highlights of the Human Career

- Racial Disparities in American Justice System

- White People's Identity in the United States

- How Homo Sapiens Influenced Felis Catus

- Multiculturalism and “White Anxiety”

- Multi-Occupancy Buildings: Community Safety

- Friendship's Philosophical Description

- Gender Stereotypes on Television

- Karen Springen's "Why We Tuned Out"

- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

- Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

Race and Ethnicity, Essay Example

Pages: 3

Words: 734

Hire a Writer for Custom Essay

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

Race refers to a person’s physical appearance.In the past, race used to be identified by the use of skin color, eye color, hair color and bone or jaw structure (Karen and Nkomo324).Conversely,ethnicity, is based on shared cultural factors such as nationality, culture, ancestry, food, languages and beliefs (Karen and Nkomo325). Currently, race identification is done by use of DNA molecules thus, physical appearances cannot give one the right race.Ethnic identification can be accepted or rejected by the person in a particular group.They are social characteristics that can either make a person to be accepted or rejected in the society (Greene and Owen 27).

Race according to sociologist are social concepts and is a way in which people are treated, for example, people treat black people different from the white.Race and ethnicity affects day-to-day life.For example, in the video, Sociologist Key Coder, when she was five years old, she was being asked what she is.Others saw Coder as Caucasian American, Spanish, others as Japanese although she was taller, darker and with some spots, this bring out clearly the aspects of racism in the society (Exploring Society Telecourse – video).

Causes of Race and ethnicity

There are four outcomes of race and ethnicity. These are stereotypes, prejudice, discrimination, and racism. Stereotypes arebehavioror a tendency of a particular group of people. When it is extreme it will be viewed as stereotypes. For example, all young people like music (Exploring Society Telecourse – Video).Prejudice is based on the stereotypes and attitudes or ideas determine how a person is treated. This is treating a person differently because of his/her race, for example, you stupid woman driver, just because she is a woman, she is treated differently. This judgment can either be positive or negative.

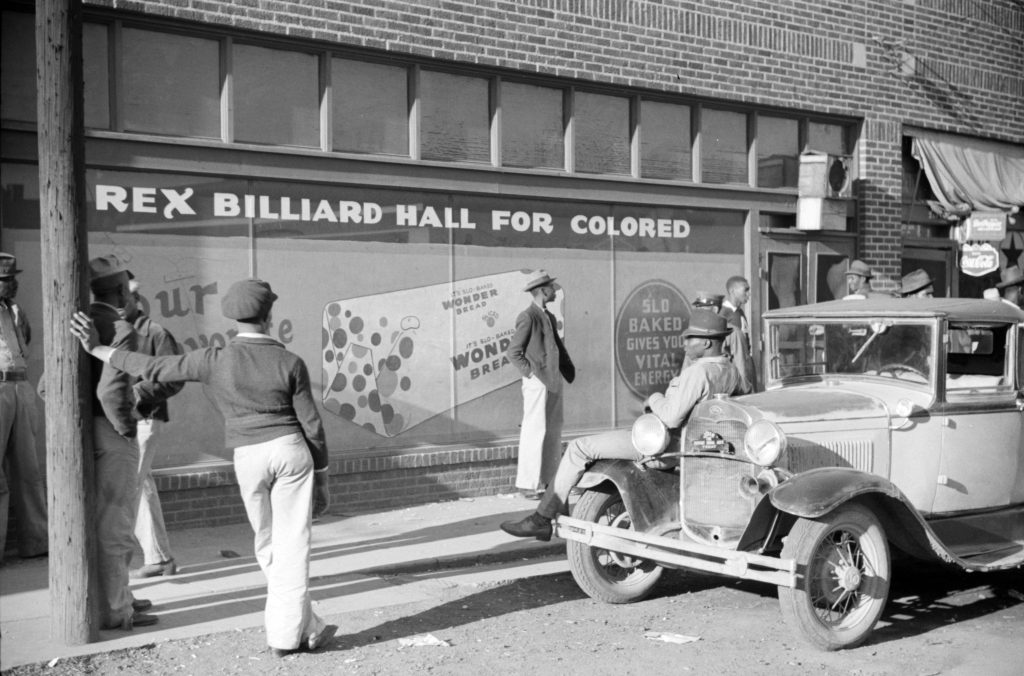

Discrimination, on the other hand, is when prejudice is acted upon. Discrimination is the acting on the attitude one has on the other.For example, having different hotels and washrooms, which are meant for white and black people (David174).Racism is discriminating people using their inherited traits. This is mostly used for the rationale of control and power. For example, during slavery the blacks were inferior and less privileged to the whites who became their masters. In racism, there is institutional racism, which is a large form of discrimination to a larger group.For example,the giving of health care services to the whites in a certain hospital and not the blacks (David, P.174).

Sociological perspective of race and ethnicity

Sociological perspective is the understanding of race and ethnicity in depth. There are three sociological perspectives; these are functionalism, conflicts, and interactionism. Functionalism indicates that race and ethnicity exist because they serve a certain purpose in the community. Leaders can use it during the war to establish a sense of belonging in a country allowing them to act as one, for example, Hitler in Germany (Exploring Society Telecourse – Video).

In conflicts perspective, race and ethnicity is used for economical and political powers. This is used for the advantage of the dominant group against the inferior group. For example, slavery was a conflict perspective because the slave acquired would work for their master, improving his wealth and political position in society. This is taking advantage of the less fortunate group (Exploring Society Telecourse – Video).Interactionism perspective is mostly in small scale and normally comes out when a certain group of people are around others. When there is a group of employees, a few will start viewing themselves differently.For example, Asians, this is because there are American and African in the same group; this is commonly known as Labeling (Exploring Society Telecourse – Video).

In conclusion, race and ethnicity impacts on the society by having people of a different race influencing the actions of the other race. This can be negative or positives,but mostly people choice to copy the positive traits or what they view as fit to them. For example, the rock and roll musicians in America, most of them being white or black acted the same way and people enjoyed their music.

Works Cited

Exploring Society Telecourse – Streaming Videos, Retrieved on 7 December 2012 From http://irt.austincc.edu/streaming/telecourses/si.html. Web.

Greene, Patricia and Margaret, Owen. “Race and ethnicity.” Handbook of entrepreneurial dynamics: The process of business creation (2004): 26-38. Print

Proudford, Karen L., and Stella Nkomo. “Race and ethnicity in organizations.” Handbook of workplace diversity. (2006): 323-344. Print.

Williams, David R. “Race, socioeconomic status, and health the added effects of racism and discrimination.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 896.1 (2006): 173-188. Print.

Stuck with your Essay?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

Ways in Which Films Have Influenced America as a Nation, Essay Example

Mariah Carey: All That Glitters Is Not Gold, Essay Example

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free guarantee

Privacy guarantee

Secure checkout

Money back guarantee

Related Essay Samples & Examples

Voting as a civic responsibility, essay example.

Pages: 1

Words: 287

Utilitarianism and Its Applications, Essay Example

Words: 356

The Age-Related Changes of the Older Person, Essay Example

Pages: 2

Words: 448

The Problems ESOL Teachers Face, Essay Example

Pages: 8

Words: 2293

Should English Be the Primary Language? Essay Example

Pages: 4

Words: 999

The Term “Social Construction of Reality”, Essay Example

Words: 371

- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples Sociology

Essay Samples on Race and Ethnicity

How does race affect social class.

How does race affect social class? Race and social class are intricate aspects of identity that intersect and influence one another in complex ways. While social class refers to the economic and societal position an individual holds, race encompasses a person's racial or ethnic background....

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Class

How Does Race Affect Everyday Life

How does race affect everyday life? Race is an integral yet often invisible aspect of our identities, influencing the dynamics of our everyday experiences. The impact of race reaches beyond individual interactions, touching various aspects of life, including relationships, opportunities, perceptions, and systemic structures. This...

Race and Ethnicity's Impact on US Employment and Criminal Justice

Since the beginning of colonialism, raced based hindrances have soiled the satisfaction of the shared and common principles in society. While racial and ethnic prejudice has diminished over the past half-century, it is still prevalent in society today. In my opinion, racial and ethnic inequity...

- American Criminal Justice System

- Criminal Justice

Why Race and Ethnicity Matter in the Social World

Not everyone is interested in educating themselves about their own roots. There are people who lack the curiosity to know the huge background that encompasses their ancestry. But if you are one of those who would like to know the diverse colors of your race...

- Ethnic Identity

The Correlation Between Race and Ethnicity and Education in the US

In-between the years 1997 and 2017, the population of the United States of America has changed a lot; especially in terms of ethnic and educational background. It grew by over 50 million people, most of which were persons of colour. Although white European Americans still make...

- Inequality in Education

Stressed out with your paper?

Consider using writing assistance:

- 100% unique papers

- 3 hrs deadline option

Damaging Effects of Social World on People of Color

Even though many are unsure or aware of what it really means to have a culture, we make claims about it everyday. The fact that culture is learned through daily experience and also learned through interactions with others, people never seem to think about it,...

- Racial Profiling

- Racial Segregation

An Eternal Conflict of Race and Ethnicity: a History of Mankind

Ethnicity is a modern concept. However, its roots go back to a long time ago. This concept took on a political aspect from the early modern period with the Peace of Westphalia law and the growth of the Protestant movement in Western Europe and the...

- Social Conflicts

Complicated Connection Between Identity, Race and Ethnicity

Different groups of people are classified based on their race and ethnicity. Race is concerned with physical characteristics, whereas ethnicity is concerned with cultural recognition. Race, on the other hand, is something you inherit, whereas ethnicity is something you learn. The connection of race, ethnicity,...

- Cultural Identity

Best topics on Race and Ethnicity

1. How Does Race Affect Social Class

2. How Does Race Affect Everyday Life

3. Race and Ethnicity’s Impact on US Employment and Criminal Justice

4. Why Race and Ethnicity Matter in the Social World

5. The Correlation Between Race and Ethnicity and Education in the US

6. Damaging Effects of Social World on People of Color

7. An Eternal Conflict of Race and Ethnicity: a History of Mankind

8. Complicated Connection Between Identity, Race and Ethnicity

- National Honor Society

- Gender Stereotypes

- Gender Roles

- Social Media

- Double Consciousness

- Community Violence

- American Dream

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

Doing Race: 21 Essays for the 21st Century

A collection of new essays by an interdisciplinary team of authors that gives a comprehensive introduction to race and ethnicity. Doing Race focuses on race and ethnicity in everyday life: what they are, how they work, and why they matter. Going to school and work, renting an apartment or buying a house, watching television, voting, listening to music, reading books and newspapers, attending religious services, and going to the doctor are all everyday activities that are influenced by assumptions about who counts, whom to trust, whom to care about, whom to include, and why. Race and ethnicity are powerful precisely because they organize modern society and play a large role in fueling violence around the globe. Doing Race is targeted to undergraduates; it begins with an introductory essay and includes original essays by well-known scholars. Drawing on the latest science and scholarship, the collected essays emphasize that race and ethnicity are not things that people or groups have or are , but rather sets of actions that people do . Doing Race provides compelling evidence that we are not yet in a “post-race” world and that race and ethnicity matter for everyone. Since race and ethnicity are the products of human actions, we can do them differently. Like studying the human genome or the laws of economics, understanding race and ethnicity is a necessary part of a twenty first century education.

inequality.com

The stanford center on poverty and inequality, search form.

- like us on Facebook

- follow us on Twitter

- See us on Youtube

Custom Search 1

- Stanford Basic Income Lab

- Social Mobility Lab

- California Lab

- Social Networks Lab

- Noxious Contracts Lab

- Tax Policy Lab

- Housing & Homelessness Lab

- Early Childhood Lab

- Undergraduate and Graduate Research Fellowships

- Minor in Poverty, Inequality, and Policy

- Certificate in Poverty and Inequality

- America: Unequal (SOC 3)

- Inequality Workshop for Doctoral Students (SOC 341W)

- Postdoctoral Scholars & Research Grants

- Research Partnerships & Technical Assistance

- Conferences

- Pathways Magazine

- Policy Blueprints

- California Poverty Measure Reports

- American Voices Project Research Briefs

- Other Reports and Briefs

- State of the Union Reports

- Multimedia Archive

- Recent Affiliate Publications

- Latest News

- Talks & Events

- California Poverty Measure Data

- American Voices Project Data

- About the Center

- History & Acknowledgments

- Center Personnel

- Stanford University Affiliates

- National & International Affiliates

- Employment & Internship Opportunities

- Graduate & Undergraduate Programs

- Postdoctoral Scholars & Research Grants

- Research Partnerships & Technical Assistance

- Talks & Events

- History & Acknowledgments

- National & International Affiliates

- Get Involved

Doing Race: 21 Essays for the 21st Century

Doing Race focuses on race and ethnicity in everyday life: what they are, how they work, and why they matter. Going to school and work, renting an apartment or buying a house, watching television, voting, listening to music, reading books and newspapers, attending religious services, and going to the doctor are all everyday activities that are influenced by assumptions about who counts, whom to trust, whom to care about, whom to include, and why. Race and ethnicity are powerful precisely because they organize modern society and play a large role in fueling violence around the globe. Doing Race is targeted to undergraduates; it begins with an introductory essay and includes original essays by well-known scholars. Drawing on the latest science and scholarship, the collected essays emphasize that race and ethnicity are not things that people or groups have or are , but rather sets of actions that people do . Doing Race provides compelling evidence that we are not yet in a “post-race” world and that race and ethnicity matter for everyone. Since race and ethnicity are the products of human actions, we can do them differently. Like studying the human genome or the laws of economics, understanding race and ethnicity is a necessary part of a twenty first century education.

Reference Information

Author: .

Emerging only in the mid 1950’s and early 1960’s as a distinct area of scholarly concern, ethnic studies has had an unsympathetic, and mostly neglected, history. The attention of historians, sociologists, anthropologists, political scientists and other humanists and social scientists has traditionally been focused on the “unique Americanness” of America. Captured symbolically by terms such as melting pot, Americanization, “American Dilemma,” “immigrant problem,” “Negro problem,” “new” and “old” immigrants and integration, the nation’s multi-cultural character has been, at once, viewed as a malady and celebrated as the socio-cultural richness that nurtured the “Great American Experiment.” Like the American people generally, scholars have had extraordinary difficulty in intellectually coping with the diversity of cultures and societies that have, in fact, determined the country’s priorities and fostered its growth.

Understanding ethnicity compels its consideration as both a concept and a process, that is, as a theoretical construct and as a system of behavioral and valuative decision-making with which individuals and groups organize life. Only in these terms is ethnicity’s separate integrity from nationality, religion, class, etc., discernable and the complexities of its relationships to these same forces revealed. Confronting ethnicity as a determinant influence also requires that its contemporary connotations and frequent misuse be comprehended. All too commonly, ethnic and blue-collar, “cracker,” racist and conservative are synonymously employed; ethnics condemned as obstacles to “enlightened” social policy; and ethnicity erroneously presumed to denote immigrant behavior, associations and value-orientations. Such simplistic notions only inhibit understanding; in fact, pose useless questions which are incapable of providing insight and clarity.

The essays compiled here examine ethnicity from many perspectives. The authors explore it conceptually–with periodic disagreement–and attempt to come to terms with its impact on American society. They serve as an introduction to this exciting and complex influence on American life. Each author raises serious questions, prods his colleagues to be increasingly sophisticated and precise, and makes a major contribution toward developing adequate methodology and scholarly perceptiveness in the study of ethnicity. The first section–Immigrants, Ethnics, Americans–combines four essays that explore the significance of ethnicity as an intellectual, scholarly tool in the study of America’s growth and development. R.A. Schermerhorn begins this section with an investigation of the relationship of ethnicity to cognition and the concomitant behavior that expresses this understanding, or knowledge. Andrew Greeley’s essay, which follows, addresses itself to the behavioral and attitudinal influence of ethnicity also, utilizing data compiled by the National Opinion Research Center. For him, the nation’s relatively placid development, when contrasted with that of other nation-states, is noteworthy, and he is convinced that the explanation for this lies in understanding both the nature of situations during which people call on ethnicity in order to cope and the circumstances under which ethnicity effects values, behavior and attitudes.

The two remaining essays examine American immigration and ethnic history. Agreeing on the need for sensitivity to the identities, institutions and communities of America’s peoples historically in order to adequately and accurately comprehend the nation’s growth, Carlton Qualey and Rudolph J. Vecoli disagree on the meaning and significance of ethnicity for explaining the lives and activities of Americans. For Professor Qualey, the dynamics of the American environment rapidly transformed immigrants into Americans whose behavior and outlooks were a function of the American experience, not European background. For Professor Vecoli, the influence of European experiences was not so transitory and the significance of ethnicity, differently conceived, is greater than Qualey would allow.

Section two–Ethnicity as Concept and Process–broadens the focus in a consideration of the nature and dynamics of ethnic influence on personal and group behavior. The five papers dissect ethnicity conceptually, explore its relationship to, for example, prescribing and proscribing behavior, intergroup relations, and raise the issue of the persistence of ethnicity over time. E.K. Francis and Joseph Fitzpatrick, the first two of this section, concentrate on the ethnic group as their approach to ethnicity. Employing the model of small group sociology as a strategy, Francis emphasizes the dynamics of group entrance and membership on behavior, values and attitudes. Fitzpatrick agrees with Francis on the fundamental significance of the group, and the sociological functions Francis describes. However, viewing the group as but one compenent of a larger entity, ethnic community, Fitzpatrick provides a broader perspective on ethnicity. Ethnic community as a cultural and affective context within which immigrants confronted a host society that was alien to them is his concern, and he closely scrutinizes community to learn its importance for identity and behavior.

Israel Rubin assesses the ethnic group as a viable context for the individual in coping with the complexities and serious issues of contemporary society. Exploring the origins and nature of ethnic group and inter-ethnic relationships historically, his conclusions-that this “frame” is incapable of satisfying the needs of individuals to any meaningful degree and that the American people, with few exceptions, appear unwilling to make the commitments which make ethnic community and behavior viable–strongly disagree with Francis and Fitzpatrick’s analyses. The “new ethnicity,” ethnic persistence, dynamics of ethnic group membership in terms of social relationships and political behavior are all approached pessimistically as Rubin questions the future of pluralistic society.

The two papers that follow approach ethnicity in terms of the mechanisms and consequences of identification. Daniel Glaser raises the essential issues of the process of ethnic identification. Discerning what he calls an “ethnic identity pattern,” he examines resultant attitudes and behavior in terms of an individual’s self-definition, those facets of a self-concept deriving from ethnic group membership, and the impact on identity stemming from inter-ethnic contact. The final study of this group investigates the nature of ethnicity beyond the first generation and the psycho-cultural-historical process of transmission. Vladimir Nahirny and Joshua Fishman challenge Marcus Lee Hansen’s famous three generation cycle and assert a new perspective.

Section three–Amalgamation, Acculturation, Assimilation–approaches ethnicity by examining the relationship of subcultural systems to a host society. Jonathan Schwartzi article introduces this unit by recalling an early 20th Century American idea about what constituted appropriate immigrant attitudes and behavior toward the United States. Focusing on Henry Ford’s attempt to literally transform, or “melt,” aliens into Americans, Schwartz illustrates both the simple-minded and intolerant perspective of many native-born people toward the complexities of inter-cultural contact situations. Immensely popular as an image, albeit often vaguely and contradictorily defined (see Philip Gleason’s excellent discussion, “Melting Pot: Symbol of Fusion or Confusion?,” American Quarterly , 16 (September, 1964)), the melting pot has been one of the most persistent descriptions of the nation’s cultural development in the 20th Century. Stanley Lieberson, author of the second essay, addresses many of the issues regarding the structure of socio-cultural organization and power relationships implicit in Ford’s efforts at “Americanization.” Attempting to create a societal formula for explaining multi- and inter-cultural contacts, he analyzes three types of experiences, assessing their dynamics to discover determinant factors and the potential for violence, repression and assimilation in each. The next essay explores what the authors believe is a necessary, but heretofore overlooked, dimension to an alien’s entrance into a host society. Broom and Kitsuse focus on the individual and assert that the relationship to the host society-acculturation and ultimately, they suggest, assimilation–is dependent upon “validation.” An individual must choose, “make an empirical test,” to be acculturated into the mainstream, they assert, and by implication no longer rely on the ethnic group for essential status, identity, norms, etc. Their’s is a challenging thesis, one with profound meaning regarding ethnicity as a persistent, fundamental influence on Americans’ lives. Walter Hirsch’s discussion raises the issue of definition. Historically reviewing the meanings, assigned to assimilation, he identifies where confusion, contradiction and ambiguity arose. Separating assimilation into two components, concept and process, Hirsch asserts a new definition he believes provides needed theoretical precision.

Section four–Ethnic Dynamics in American Society–examines the influence and expressions of ethnicity in politics, economics, and social institutions. Ethnicity’s relationship to political and other associational behavior is the concern of Michael Parenti. Criticizing scholars who would limit their study of ethnicity’s influence to searching for immigrant behavior, Parenti asserts a dynamic concept of ethnicity and stresses the need for new kinds of thinking and new questions. Ranging from politics to residential patterns to social and religious activities, his assessment is that ethnicity is not only a persistent societal force, but a determinant criteria with which people make choices and define their lives. Ronald Busch acknowledges the significance of ethnicity for political behavior, but his focus is on the qualitative nature and consequences of ethnic politics. The framework he employs in investigating the character of these politics is one that assesses the issues about which greatest concern is expressed: substantive, socio-economic considerations vs. the pursuit of and demand for recognition. For Busch, the latter defines ethnic politics and, he suggests, the consequences have been costly in allowing unsympathetic and hostile interests to rule. He proposes, also, that a new politics is rapidly emerging, one concomitant to what he perceives as an increasing rate of assimilation and focused on substantive matters. Clearly, the challenges of his analysis are many. Ethnicity’s relationship to the ability to achieve desires politically, ethnic politics as a means of manipulating constituencies, co-opting potential opposition, and hiding real issues, the persistence of ethnicity as a political liability, assimilation as the key to achieving and effectively utilizing political power are but some of the serious issues that Busch raises and which must be confronted.

Christen Jonassen adds a new dimension to the influence of ethnicity on behavior. Focusing on the spatial movement of a Norwegian community over many decades, he stresses the critical role of ethnicity in determining locations and maintaining the community’s integrity as a cohesive, identifiable entity. His analysis compels investigators to consider far more than the influence of “biotic,” or impersonal, natural, and economic forces on mobility. For Jonassen, there must be an awareness of the socio-cultural framework of a community which regulates competition over such things as housing, jobs, status, etc. and influences values and behavior.

The book closes with a very different kind of document than that which composes its bulk. Significant not for its historical breadth, nor for its analytical sophistication, Anthony Celebrezze’s personal comments underscore the premises upon which this compilation was developed. Like Mr. Celebrezze, the scholars in this volume and I are convinced that “ours is a nation which must be uniquely aware of that quality which has come to be called ethnicity.” It has been a fundamental, essential influence on America’s history, molding–often determining–the nature and intensity of behavior in religion, politics, family organization, occupation, education, and community development and character.

Ethnicity Copyright © 2020 by Cleveland State University . All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

Module 8: Race and Ethnicity

Introduction to race and ethnicity in the united states, what you’ll learn: compare and contrast the experiences of racial and ethnic groups in the united states.

Figure 1 . The Freedom Riders were a civil rights activist group that rode interstate buses into southern states in the U.S. that refused to enforce anti-segregation laws even after segregation was nationally outlawed. The Freedom Riders were often arrested in these states while challenging the continuing local practice of segregation. (Photo courtesy of Adam Jones/Wikimedia Commons)

When the first European explorers came to the New World in 1492, Native Americans had been on the continent for 15,000 years. The brutal suppression of Native American tribes all over the United States is unfortunately not so different from the treatment of other minority groups in U.S. history. Slavery began with the forced importation of slaves in 1619 and continued until 1865, but mistreatment and abuse persisted well into the post-slavery era.

Like the Native Americans, other groups had their lands stolen, or obtained through forced treaties. Consider the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848) in which Mexico signed away 525,000 square miles, including what is today Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming. The Treaty guaranteed both land rights and citizenship (retain Mexican citizenship or become U.S. citizens) and official documents were bilingual; the first “English-only” rule was created thirty years later in 1878 [1] . The reality, however, was quite different. Most Mexican landowners lost their land within a few decades and had little or no legal recourse. We hear a lot about immigration today, but much less about the history of these groups, or about how that history helps us to understand the contemporary experiences of minority groups in the U.S.

Waves of immigrants came from various parts of the world for a variety of reasons; see a timeline showing push and pull factors affecting immigration . Most of these groups underwent a period of disenfranchisement in which they were relegated to the bottom of the social hierarchy. In the same period, racist ideologies persisted, and often resulted in discrimination and systemic inequalities that still affect Black and brown peoples in the U.S. today.

Our society is multicultural and filled with diverse groups that are reflected in American culture, but we must use our sociological imaginations to examine history and biography to truly understand race and ethnicity in the United States today. Similar to the example of “Stratified Monopoly” from the social stratification readings, racial and ethnic minority groups do not start at “GO” with the same resources. For Native American, Mexican American and African American peoples, a variety of mechanisms prevented them from owning land, a significant source of wealth and power in the United States that has generational socioeconomic effects.

This section will describe how several groups became part of U.S. society, discuss the history of intergroup relations, and briefly assess each group’s status today.

The U.S. Census Bureau collects racial data in accordance with guidelines provided by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget (OMB 2016). These data are based on self-identification; generally reflect a social definition of race recognized in this country that include racial and national origin or sociocultural groups. People may choose to report more than one race to indicate their racial mixture, such as “American Indian” and “White.” People who identify their origin as Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish may be of any race. OMB requires five minimum categories: White, Black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander. The U.S. Census Bureau’s QuickFacts as of July 1, 2019 showed that over 328 million people representing various racial groups were living in the U.S. (Table 11.1).

- White – A person having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa.

- Black or African American – A person having origins in any of the Black racial groups of Africa.

- American Indian or Alaska Native – A person having origins in any of the original peoples of North and South America (including Central America) and who maintains tribal affiliation or community attachment.

- Asian – A person having origins in any of the original peoples of the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent including, for example, Cambodia, China, India, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippine Islands, Thailand, and Vietnam.

- Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander – A person having origins in any of the original peoples of Hawaii, Guam, Samoa, or other Pacific Islands.

Information on race is required for many Federal programs and is critical in making policy decisions, particularly for civil rights including racial justice. States use these data to meet legislative redistricting principles. Race data also are used to promote equal employment opportunities and to assess racial disparities in health and environmental risks that demonstrates the extent to which this multiculturality is embraced. The many manifestations of multiculturalism carry significant political repercussions. The sections below will describe how several groups became part of U.S. society, discuss the history of intergroup relations for each faction, and assess each group’s status today.

Contribute!

Improve this page Learn More

- Oliver, P. 2017. "What the Treaty of Guadalupe Really Says." University of Wisconsin Madison. https://www.ssc.wisc.edu/soc/racepoliticsjustice/2017/07/12/what-the-treaty-of-guadalupe-actually-says/ ↵

- Introduction to Race and Ethnicity in the United States. Authored by : Sarah Hoiland for Lumen Learning. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Revision, Modification, and Original Content. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Race and Ethnicity in the United States Derived from Race and Ethnicity in the United States by OpenStax. Authored by : OpenStax CNX. Located at : https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/11-5-race-and-ethnicity-in-the-united-states . Project : Sociology 3e. License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Exhibit on Freedom Riders - Center for Civil and Human Rights - Atlanta - Georgia. Authored by : Adam Jones. Provided by : Wikimedia Commons. Located at : https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Exhibit_on_Freedom_Riders_-_Center_for_Civil_and_Human_Rights_-_Atlanta_-_Georgia_-_USA_(33468216774).jpg . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Race & Ethnicity: Crash Course Sociology #34. Provided by : CrashCourse. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7myLgdZhzjo&index=35&list=PL8dPuuaLjXtMJ-AfB_7J1538YKWkZAnGA . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

5.3: Writing about Race, Ethnic, and Cultural Identity: A Process Approach

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 14822

To review, race, ethnic, and cultural identity theory provides us with a particular lens to use when we read and interpret works of literature. Such reading and interpreting, however, never happens after just a first reading; in fact, all critics reread works multiple times before venturing an interpretation. You can see, then, the connection between reading and writing: as Chapter 1 indicates, writers create multiple drafts before settling for a finished product. The writing process, in turn, is dependent on the multiple rereadings you have performed to gather evidence for your essay. It’s important that you integrate the reading and writing process together. As a model, use the following ten-step plan as you write using race, ethnic, and cultural identity theory:

- Carefully read the work you will analyze.

- Formulate a general question after your initial reading that identifies a problem—a tension—related to a historical or cultural issue.

- Reread the work , paying particular attention to the question you posed. Take notes, which should be focused on your central question. Write an exploratory journal entry or blog post that allows you to play with ideas.

- What does the work mean?

- How does the work demonstrate the theme you’ve identified using a new historical approach?

- “So what” is significant about the work? That is, why is it important for you to write about this work? What will readers learn from reading your interpretation? How does the theory you apply illuminate the work’s meaning?

- Reread the text to gather textual evidence for support.

- Construct an informal outline that demonstrates how you will support your interpretation.

- Write a first draft.

- Receive feedback from peers and your instructor via peer review and conferencing with your instructor (if possible).

- Revise the paper , which will include revising your original thesis statement and restructuring your paper to best support the thesis. Note: You probably will revise many times, so it is important to receive feedback at every draft stage if possible.

- Edit and proofread for correctness, clarity, and style.

We recommend that you follow this process for every paper that you write from this textbook. Of course, these steps can be modified to fit your writing process, but the plan does ensure that you will engage in a thorough reading of the text as you work through the writing process, which demands that you allow plenty of time for reading, reflecting, writing, reviewing, and revising.

Peer Reviewing

A central stage in the writing process is the feedback stage, in which you receive revision suggestions from classmates and your instructor. By receiving feedback on your paper, you will be able to make more intelligent revision decisions. Furthermore, by reading and responding to your peers’ papers, you become a more astute reader, which will help when you revise your own papers. In Chapter 10, you will find peer-review sheets for each chapter.

Introduction to Race and Ethnicity

Chapter outline.

Trayvon Martin was a seventeen-year-old black teenager. On the evening of February 26, 2012, he was visiting with his father and his father’s fiancée in the Sanford, Florida multi-ethnic gated community where his father's fiancée lived. Trayvon went on foot to buy a snack from a nearby convenience store. As he was returning, George Zimmerman, a white Hispanic male and the community’s neighborhood watch program coordinator, noticed him. In light of a recent rash of break-ins, Zimmerman called the police to report a person acting suspiciously, which he had done on many other occasions. The 911 operator told Zimmerman not to follow the teen, but soon after Zimmerman and Martin had a physical confrontation. According to Zimmerman, Martin attacked him, and in the ensuing scuffle Martin was shot and killed (CNN Library 2014).

A public outcry followed Martin’s death. There were allegations of racial profiling —the use by law enforcement of race alone to determine whether to stop and detain someone—a national discussion about “Stand Your Ground Laws,” and a failed lawsuit in which Zimmerman accused NBC of airing an edited version of the 911 call that made him appear racist. Zimmerman was not arrested until April 11, when he was charged with second-degree murder by special prosecutor Angela Corey. In the ensuing trial, he was found not guilty (CNN Library 2014).

The shooting, the public response, and the trial that followed offer a snapshot of the sociology of race. Do you think race played a role in Martin’s death or in the public reaction to it? Do you think race had any influence on the initial decision not to arrest Zimmerman, or on his later acquittal? Does society fear black men, leading to racial profiling at an institutional level? What about the role of the media? Was there a deliberate attempt to manipulate public opinion? If you were a member of the jury, would you have convicted George Zimmerman?

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/1-introduction-to-sociology

- Authors: Heather Griffiths, Nathan Keirns

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Introduction to Sociology 2e

- Publication date: Apr 24, 2015

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/1-introduction-to-sociology

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/11-introduction-to-race-and-ethnicity

© Feb 9, 2022 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

SOC101: Introduction to Sociology (2020.A.01)

Race and ethnicity.

Read this chapter for a review of race and ethnicity. As you read through each section, consider the following points:

- Can you identify areas in your life where race and ethnicity have an effect?

- Take note of the differences between race and ethnicity. Explore the idea behind race being a social construction, rather than a biological identifier. Take note of the definitions of majority and minority groups.

- Take note of the differences between stereotypes, prejudice, discrimination, and racism. Challenge yourself to think about some common stereotypes you might be familiar with.

- Read about how the major theoretical perspectives view race and ethnicity. On a separate piece of paper, make a list of examples of culture of prejudice. For example, when you see an actor of (presumably) Middle Eastern descent in a film, how often are they either the hero or the villain? When you're watching television and commercials come on, what are some common themes you notice in the racial categories of the actors? How about images in high fashion magazines? Often times, when women of color appear in these ads, they are eroticized in some way, creating a visual of someone who is less than human.

- Take note of the definitions of genocide, expulsion, segregation, pluralism, and assimilation. Also, pay attention to amalgamation and how it is somewhat similar to the classic melting pot theory.

- Focus on the different experiences of various ethnic groups in the United States. Due to the current racial stratification in the U.S., how might race or ethnicity affect access to valuable resources like education or health care?

Racial, Ethnic, and Minority Groups

Race is fundamentally a social construct. Ethnicity is a term that describes shared culture and national origin. Minority groups are defined by their lack of power.

Stereotypes, Prejudice, and Discrimination

Stereotypes are oversimplified ideas about groups of people. Prejudice refers to thoughts and feelings, while discrimination refers to actions. Racism refers to the belief that one race is inherently superior or inferior to other races.

Theories of Race and Ethnicity

Functionalist views of race study the role dominant and subordinate groups play to create a stable social structure. Conflict theorists examine power disparities and struggles between various racial and ethnic groups. Interactionists see race and ethnicity as important sources of individual identity and social symbolism. The concept of culture of prejudice recognizes that all people are subject to stereotypes that are ingrained in their culture.

Intergroup Relationships

Intergroup relations range from a tolerant approach of pluralism to intolerance as severe as genocide. In pluralism, groups retain their own identity. In assimilation, groups conform to the identity of the dominant group. In amalgamation, groups combine to form a new group identity.

Race and Ethnicity in the United States

The history of the U.S. people contains an infinite variety of experiences that sociologist understand follow patterns. From the indigenous people who first inhabited these lands to the waves of immigrants over the past 500 years, migration is an experience with many shared characteristics. Most groups have experienced various degrees of prejudice and discrimination as they have gone through the process of assimilation.

ReviseSociology

A level sociology revision – education, families, research methods, crime and deviance and more!

An Introduction to Ethnicity

ethnicity is cultural, and often contrasted to ‘race’ which refers to biological differences.

Last Updated on January 20, 2023 by Karl Thompson

Ethnicity refers to a type of social identity based on cultural background, shared lifestyles and shared experiences. Several characteristics may serve as sources of a collective identity such as: language, a sense of shared history or ancestry, religion, shared beliefs and values.

Ethnic groups are ‘imagined communities’ whose existence depends on the self-identification of their members. Members of ethnic groups may see themselves as culturally distinct from other groups, and are seen, in turn, as different. In this sense, ethnic groups always co-exist with other ethnic groups.

When sociologists use the term ethnicity they usually contrast it to the historically discredited concept of race. Ethnicity refers to an active source of identity rooted in culture and society which means it is different to the concept of race which has historically been defined as something fixed and biological.

Ethnicity is learned, there is nothing innate about it, it has to be actively passed down through the generations by the process of socialisation. It follows that for some people, ethnicity is a very important source of identity, for others it means nothing at all, and for some it only becomes important at certain points in their lives – maybe when they get married or during religious festivals, or maybe during a period of conflict in a country.

Because it is rooted in culture, people’s sense of their ethnic identities can change over time and become more or less active in particular social contexts.

However some members of some ethnic groups may perceive the idea of race as important to their sense of shared identity. Some people may believe that they are of one particular race based on their particular biological characteristics or their shared ancestry and believe that only people with whom they perceive as having the same ‘racial’ characteristics belong to their in-group.

For comparative purposes you might like to read this post: an introduction to the concept of race for sociology students .

Problems with the concept of ethnicity

Majority ethnic groups are still ‘ethnic groups’. However, there is often a tendency to label the majority ethnic group, e.g. the ‘white-British’ group as non-ethnic, and all other minority ethnic groups as ‘ethnic minorities’. This results in the majority group regarding themselves as ‘the norm’ from which all other minority ethnic groups diverge.

There is also a tendency to oversimplify the concept of ethnicity – a good example of this is when job application forms ask for your ethnic identity (ironically to track equality of opportunity) and offer a limited range of categories such as Asian, African, Caribbean, White and so on, which fails to recognize that there are a number of different ethnic identities within each of these broader (misleading?) categories.

Sources use to write this post

Giddens and Sutton (2017) Sociology

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Discover more from ReviseSociology

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

2.3 Introduction to Race and Ethnicity

Racial, ethnic, and minority groups.

While many students first entering a sociology classroom are accustomed to conflating the terms “race,” “ethnicity,” and “minority group,” these three terms have distinct meanings for sociologists. The idea of race refers to superficial physical differences that a particular society considers significant, while ethnicity describes shared culture. And the term “minority groups” describe groups that are subordinate, or that lack power in society regardless of skin color or country of origin. For example, in modern U.S. history, the elderly might be considered a minority group due to a diminished status that results from popular prejudice and discrimination against them. Ten percent of nursing home staff admitted to physically abusing an elderly person in the past year, and 40% admitted to committing psychological abuse (World Health Organization, 2011). In this chapter we focus on racial and ethnic minorities.

What Is Race?

Historically, the concept of race has changed across cultures and eras, and has eventually become less connected with ancestral and familial ties, and more concerned with superficial physical characteristics. In the past, theorists have posited categories of race based on various geographic regions, ethnicities, skin colors, and more. Their labels for racial groups have connoted regions (Mongolia and the Caucus Mountains, for instance) or skin tones (black, white, yellow, and red, for example).

Social science organizations including the American Association of Anthropologists, the American Sociological Association, and the American Psychological Association have all taken an official position rejecting the biological explanations of race. Over time, the typology of race that developed during early racial science has fallen into disuse, and the social construction of race is a more sociological way of understanding racial categories. Research in this school of thought suggests that race is not biologically identifiable and that previous racial categories were arbitrarily assigned, based on pseudoscience, and used to justify racist practices (Omi & Winant, 1994; Graves, 2003). When considering skin color, for example, the social construction of race perspective recognizes that the relative darkness or fairness of skin is an evolutionary adaptation to the available sunlight in different regions of the world. Contemporary conceptions of race, therefore, which tend to be based on socioeconomic assumptions, illuminate how far removed modern understanding of race is from biological qualities. In modern society, some people who consider themselves “White” actually have more melanin (a pigment that determines skin color) in their skin than other people who identify as ”Black.” Consider the case of the actress Rashida Jones. She is the daughter of a Black man (Quincy Jones), and her best-known roles include Ann Perkins on Parks and Recreation, Karen Filippelli on The Office, and Zooey Rice in I Love You Man, none of whom are Black characters. In some countries, such as Brazil, class is more important than skin color in determining racial categorization. People with high levels of melanin may consider themselves “White” if they enjoy a middle-class lifestyle. On the other hand, someone with low levels of melanin might be assigned the identity of “Black” if he or she has little education or money.

The social construction of race is also reflected in the way names for racial categories change with changing times. It’s worth noting that race, in this sense, is also a system of labeling that provides a source of identity; specific labels fall in and out of favor during different social eras. For example, the category ”negroid,” popular in the nineteenth century, evolved into the term “negro” by the 1960s, and then this term fell from use and was replaced with “African American.” This latter term was intended to celebrate the multiple identities that a Black person might hold, but the word choice is a poor one: it lumps together a large variety of ethnic groups under an umbrella term while excluding others who could accurately be described by the label but who do not meet the spirit of the term. For example, actress Charlize Theron is a blonde-haired, blue-eyed “African American.” She was born in South Africa and later became a U.S. citizen. Is her identity that of an “African American” as most of us understand the term?

What Is Ethnicity?

Ethnicity is a term that describes shared culture—the practices, values, and beliefs of a group. This culture might include shared language, religion, and traditions, among other commonalities. Like race, the term ethnicity is difficult to describe and its meaning has changed over time. And as with race, individuals may be identified or self-identify with ethnicities in complex, even contradictory, ways. For example, ethnic groups such as Irish, Italian American, Russian, Jewish, and Serbian might all be groups whose members are predominantly included in the “White” racial category. Conversely, the ethnic group British includes citizens from a multiplicity of racial backgrounds: Black, White, Asian, and more, plus a variety of race combinations. These examples illustrate the complexity and overlap of these identifying terms. Ethnicity, like race, continues to be an identification method that individuals and institutions use today—whether through the census, affirmative action initiatives, nondiscrimination laws, or simply in personal day-to-day relations.

What Are Minority Groups?

Sociologist Louis Wirth (1945) defined a minority group as “any group of people who, because of their physical or cultural characteristics, are singled out from the others in the society in which they live for differential and unequal treatment, and who therefore regard themselves as objects of collective discrimination.” The term minority connotes discrimination, and in its sociological use, the term subordinate group can be used interchangeably with the term minority, while the term dominant group is often substituted for the group that’s in the majority. These definitions correlate to the concept that the dominant group is that which holds the most power in a given society, while subordinate groups are those who lack power compared to the dominant group.

Note that being a numerical minority is not a characteristic of being a minority group; sometimes larger groups can be considered minority groups due to their lack of power. It is the lack of power that is the predominant characteristic of a minority, or subordinate group. For example, consider apartheid in South Africa, in which a numerical majority (the Black inhabitants of the country) were exploited and oppressed by the White minority.

According to Charles Wagley and Marvin Harris (1958), a minority group is distinguished by five characteristics: (1) unequal treatment and less power over their lives, (2) distinguishing physical or cultural traits like skincolor or language, (3) involuntary membership in the group, (4) awareness of subordination, and (5) high rate of in-group marriage. Additional examples of minority groups might include the LBGT community, religious practitioners whose faith is not widely practiced where they live, and people with disabilities.

Scapegoat theory, developed initially from Dollard et al.’s (1939) Frustration-Aggression theory, suggests that the dominant group will displace its unfocused aggression onto a subordinate group. History has shown us many examples of the scapegoating of a subordinate group. An example from the last century is the way Adolf Hitler was able to blame the Jewish population for Germany’s social and economic problems. In the United States, recent immigrants have frequently been the scapegoat for the nation’s—or an individual’s—woes. Many states have enacted laws to disenfranchise immigrants; these laws are popular because they let the dominant group scapegoat a subordinate group.

DISCRIMINATION, STEREOTYPES, PREJUDICE AND RACE

The terms stereotype, prejudice, discrimination, and racism are often used interchangeably in everyday conversation. Let us explore the differences between these concepts. Stereotypes are oversimplified generalizations about groups of people. Stereotypes can be based on race, ethnicity, age, gender, sexual orientation—almost any characteristic. They may be positive (usually about one’s own group, such as when women suggest they are less likely to complain about physical pain) but are often negative (usually toward other groups, such as when members of a dominant racial group suggest that a subordinate racial group is stupid or lazy). In either case, the stereotype is a generalization that doesn’t take individual differences into account.

Where do stereotypes come from? In fact new stereotypes are rarely created; rather, they are recycled from subordinate groups that have assimilated into society and are reused to describe newly subordinate groups. For example, many stereotypes that are currently used to characterize Black people were used earlier in American history to characterize Irish and Eastern European immigrants.

Prejudice and Racism

Prejudice refers to the beliefs, thoughts, feelings, and attitudes someone holds about a group. A prejudice is not based on experience; instead, it is a prejudgment, originating outside actual experience. A 1970 documentary called Eye of the Storm illustrates the way in which prejudice develops, by showing how defining one category of people as superior (children with blue eyes) results in prejudice against people who are not part of the favored category.

While prejudice is not necessarily specific to race, racism is a stronger type of prejudice used to justify the belief that one racial category is somehow superior or inferior to others; it is also a set of practices used by a racial majority to disadvantage a racial minority. The Ku Klux Klan is an example of a racist organization; its members’ belief in White supremacy has encouraged over a century of hate crime and hate speech.

Institutional racism refers to the way in which racism is embedded in the fabric of society. For example, the disproportionate number of Black men arrested, charged, and convicted of crimes may reflect racial profiling, a form of institutional racism.

Colorism is another kind of prejudice, in which someone believes one type of skin tone is superior or inferior to another within a racial group. Studies suggest that darker skinned African Americans experience more discrimination than lighter skinned African Americans (Herring et al., 2004; Klonoff & Landrine, 2000). For example, if a White employer believes a Black employee with a darker skin tone is less capable than a Black employee with lighter skin tone, that is colorism. At least one study suggested the colorism affected racial socialization, with darker-skinned Black male adolescents receiving more warnings about the danger of interacting with members of other racial groups than did lighter-skinned Black male adolescents (Landor et al., 2013).

Discrimination

While prejudice refers to biased thinking, discrimination consists of actions against a group of people. Discrimination can be based on age, religion, health, and other indicators; race-based laws against discrimination strive to address this set of social problems.

Discrimination based on race or ethnicity can take many forms, from unfair housing practices to biased hiring systems. Overt discrimination has long been part of U.S. history. In the late nineteenth century, it was not uncommon for business owners to hang signs that read, “Help Wanted: No Irish Need Apply.” And southern Jim Crow laws, with their “Whites Only” signs, exemplified overt discrimination that is not tolerated today.

However, we cannot erase discrimination from our culture just by enacting laws to abolish it. Even if a magic pill managed to eradicate racism from each individual’s psyche, society itself would maintain it. Sociologist Émile Durkheim (1982) calls racism a social fact, meaning that it does not require the action of individuals to continue. The reasons for this are complex and relate to the educational, criminal, economic, and political systems that exist in our society.

For example, when a newspaper identifies by race individuals accused of a crime, it may enhance stereotypes of a certain minority. Another example of racist practices is racial steering, in which real estate agents direct prospective homeowners toward or away from certain neighborhoods based on their race. Racist attitudes and beliefs are often more insidious and harder to pin down than specific racist practices.

Prejudice and discrimination can overlap and intersect in many ways. To illustrate, here are four examples of how prejudice and discrimination can occur. Unprejudiced nondiscriminators are open-minded, tolerant, and accepting individuals. Unprejudiced discriminators might be those who unthinkingly practice sexism in their workplace by not considering females for certain positions that have traditionally been held by men. Prejudiced nondiscriminators are those who hold racist beliefs but don’t act on them, such as a racist store owner who serves minority customers. Prejudiced discriminators include those who actively make disparaging remarks about others or who perpetrate hate crimes.

Discrimination also manifests in different ways. The scenarios above are examples of individual discrimination, but other types exist. Institutional discrimination occurs when a societal system has developed with embedded disenfranchisement of a group, such as the U.S. military’s historical nonacceptance of minority sexualities (the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy reflected this norm).

Institutional discrimination can also include the promotion of a group’s status, such in the case of White privilege, which is the benefits people receive simply by being part of the dominant group (McIntosh, 1989).

While most White people are willing to admit that non-White people live with a set of disadvantages due to the color of their skin, very few are willing to acknowledge the benefits they receive.

Racial Tensions in the United States

The death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, on August 9, 2014, illustrates racial tensions in the United States as well as the overlap between prejudice, discrimination, and institutional racism. On that day, Brown, a young unarmed Black man, was killed by a White police officer named Darren Wilson. During the incident, Wilson directed Brown and his friend to walk on the sidewalk instead of in the street. While eyewitness accounts vary, they agree that an altercation occurred between Wilson and Brown. Wilson’s version has him shooting Brown in self-defense after Brown assaulted him, while Dorian Johnson, a friend of Brown also present at the time, claimed that Brown first ran away, then turned with his hands in the air to surrender, after which Wilson shot him repeatedly (Nobles & Bosman, 2014). Three autopsies independently confirmed that Brown was shot six times (Lowery & Fears, 2014).

The shooting focused attention on a number of race-related tensions in the United States. First, members of the predominantly Black community viewed Brown’s death as the result of a White police officer racially profiling a Black man (Nobles & Bosman, 2014). In the days after, it was revealed that only three members of the town’s fifty-three-member police force were Black (Nobles & Bosman, 2014). The national dialogue shifted during the next few weeks, with some commentators pointing to a nationwide sedimentation of racial inequality and identifying redlining in Ferguson as a cause of the unbalanced racial composition in the community, in local political establishments, and in the police force (Bouie, 2014). Redlining is the practice of routinely refusing mortgages for households and businesses located in predominately minority communities, while sedimentation of racial inequality describes the intergenerational impact of both practical and legalized racism that limits the abilities of Black people to accumulate wealth.

Ferguson’s racial imbalance may explain in part why, even though in 2010 only about 63% of its population was Black, in 2013 Blacks were detained in 86% of stops, 92% of searches, and 93% of arrests (Missouri Attorney General’s Office, 2014). In addition, de facto segregation in Ferguson’s schools, a race-based wealth gap, urban sprawl, and a Black unemployment rate three times that of the White unemployment rate worsened existing racial tensions in Ferguson while also reflecting nationwide racial inequalities (Bouie, 2014).

Multiple Identities

Prior to the twentieth century, racial intermarriage (referred to as miscegenation) was extremely rare, and in many places, illegal. In the later part of the twentieth century and in the twenty-first century, as Figure 4.1 shows, attitudes have changed for the better. While the sexual subordination of slaves did result in children of mixed race, these children were usually considered Black, and therefore, property. There was no concept of multiple racial identities with the possible exception of the Creole. Creole society developed in the port city of New Orleans, where a mixed-race culture grew from French and African inhabitants. Unlike in other parts of the country, “Creoles of color” had greater social, economic, and educational opportunities than most African Americans (Caver & Williams, 2011).

Increasingly during the modern era, the removal of miscegenation laws and a trend toward equal rights and legal protection against racism have steadily reduced the social stigma attached to racial exogamy (exogamy refers to marriage outside a person’s core social unit). It is now common for the children of racially mixed parents to acknowledge and celebrate their various ethnic identities. Golfer Tiger Woods, for instance, has Chinese, Thai, African American, Native American, and Dutch heritage; he jokingly refers to his ethnicity as “Cablinasian,” a term he coined to combine several of his ethnic backgrounds. While this is the trend, it is not yet evident in all aspects of our society. For example, the U.S. Census only recently added additional categories for people to identify themselves, such as non-White Hispanic. A growing number of people chose multiple races to describe themselves on the 2010 Census, paving the way for the 2020 Census to provide yet more choices.

(https://news.gallup.com/poll/163697/approve-marriage-blacks-whites.aspx)

(This work, Approval of Interracial Marriage US, is a derivative of Public opinion of interracial marriage in the United States by Yerevanci/Wikimedia Commons, used under CC BY-SA 3.0. Approval of Interracial Marriage US is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 by Judy Schmitt.)]

THEORIES OF RACE AND ETHNICITY

Theoretical perspectives.

We can examine issues of race and ethnicity through three major sociological perspectives: functionalism, conflict theory, and symbolic interactionism. As you read through these theories, ask yourself which one makes the most sense and why. Do we need more than one theory to explain racism, prejudice, stereotypes, and discrimination?

Functionalism

In the view of functionalism, racial and ethnic inequalities must have served an important function in order to exist as long as they have. This concept, of course, is problematic. How can racism and discrimination contribute positively to society? A functionalist might look at “functions” and “dysfunctions” caused by racial inequality. Nash (1964) focused his argument on the way racism is functional for the dominant group, for example, suggesting that racism morally justifies a racially unequal society. Consider the way slave owners justified slavery in the antebellum South, by suggesting Black people were fundamentally inferior to White and preferred slavery to freedom.

Another way to apply the functionalist perspective to racism is to discuss the way racism can contribute positively to the functioning of society by strengthening bonds between in-group members through the ostracism of out-group members. Consider how a community might increase solidarity by refusing to allow outsiders access. On the other hand, Rose (1958) suggested that dysfunctions associated with racism include the failure to take advantage of talent in the subjugated group, and that society must divert from other purposes the time and effort needed to maintain artificially constructed racial boundaries. Consider how much money, time, and effort went toward maintaining separate and unequal educational systems prior to the civil rights movement.

Conflict Theory