Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write a rhetorical analysis | Key concepts & examples

How to Write a Rhetorical Analysis | Key Concepts & Examples

Published on August 28, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

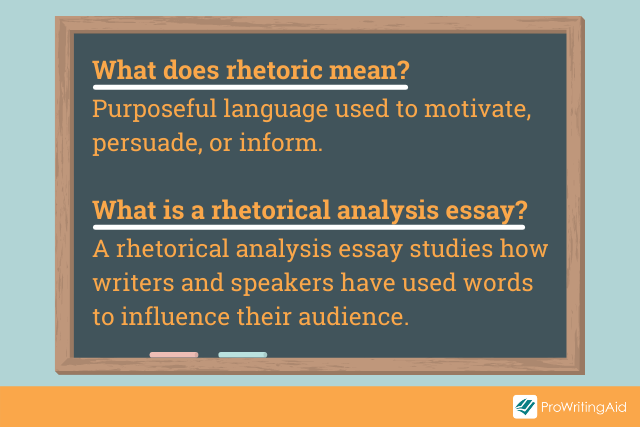

A rhetorical analysis is a type of essay that looks at a text in terms of rhetoric. This means it is less concerned with what the author is saying than with how they say it: their goals, techniques, and appeals to the audience.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Key concepts in rhetoric, analyzing the text, introducing your rhetorical analysis, the body: doing the analysis, concluding a rhetorical analysis, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about rhetorical analysis.

Rhetoric, the art of effective speaking and writing, is a subject that trains you to look at texts, arguments and speeches in terms of how they are designed to persuade the audience. This section introduces a few of the key concepts of this field.

Appeals: Logos, ethos, pathos

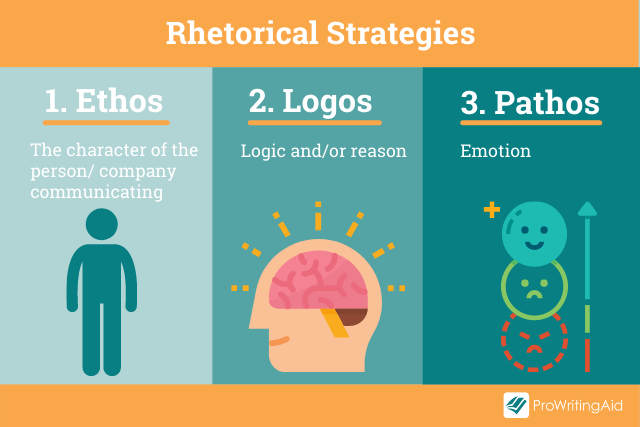

Appeals are how the author convinces their audience. Three central appeals are discussed in rhetoric, established by the philosopher Aristotle and sometimes called the rhetorical triangle: logos, ethos, and pathos.

Logos , or the logical appeal, refers to the use of reasoned argument to persuade. This is the dominant approach in academic writing , where arguments are built up using reasoning and evidence.

Ethos , or the ethical appeal, involves the author presenting themselves as an authority on their subject. For example, someone making a moral argument might highlight their own morally admirable behavior; someone speaking about a technical subject might present themselves as an expert by mentioning their qualifications.

Pathos , or the pathetic appeal, evokes the audience’s emotions. This might involve speaking in a passionate way, employing vivid imagery, or trying to provoke anger, sympathy, or any other emotional response in the audience.

These three appeals are all treated as integral parts of rhetoric, and a given author may combine all three of them to convince their audience.

Text and context

In rhetoric, a text is not necessarily a piece of writing (though it may be this). A text is whatever piece of communication you are analyzing. This could be, for example, a speech, an advertisement, or a satirical image.

In these cases, your analysis would focus on more than just language—you might look at visual or sonic elements of the text too.

The context is everything surrounding the text: Who is the author (or speaker, designer, etc.)? Who is their (intended or actual) audience? When and where was the text produced, and for what purpose?

Looking at the context can help to inform your rhetorical analysis. For example, Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech has universal power, but the context of the civil rights movement is an important part of understanding why.

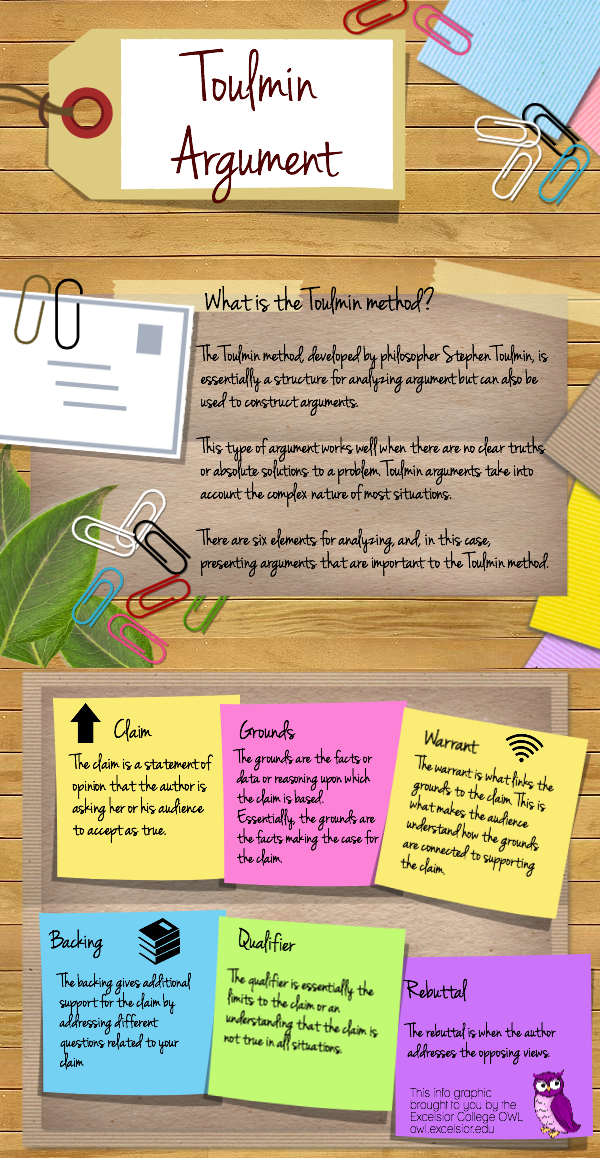

Claims, supports, and warrants

A piece of rhetoric is always making some sort of argument, whether it’s a very clearly defined and logical one (e.g. in a philosophy essay) or one that the reader has to infer (e.g. in a satirical article). These arguments are built up with claims, supports, and warrants.

A claim is the fact or idea the author wants to convince the reader of. An argument might center on a single claim, or be built up out of many. Claims are usually explicitly stated, but they may also just be implied in some kinds of text.

The author uses supports to back up each claim they make. These might range from hard evidence to emotional appeals—anything that is used to convince the reader to accept a claim.

The warrant is the logic or assumption that connects a support with a claim. Outside of quite formal argumentation, the warrant is often unstated—the author assumes their audience will understand the connection without it. But that doesn’t mean you can’t still explore the implicit warrant in these cases.

For example, look at the following statement:

We can see a claim and a support here, but the warrant is implicit. Here, the warrant is the assumption that more likeable candidates would have inspired greater turnout. We might be more or less convinced by the argument depending on whether we think this is a fair assumption.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Rhetorical analysis isn’t a matter of choosing concepts in advance and applying them to a text. Instead, it starts with looking at the text in detail and asking the appropriate questions about how it works:

- What is the author’s purpose?

- Do they focus closely on their key claims, or do they discuss various topics?

- What tone do they take—angry or sympathetic? Personal or authoritative? Formal or informal?

- Who seems to be the intended audience? Is this audience likely to be successfully reached and convinced?

- What kinds of evidence are presented?

By asking these questions, you’ll discover the various rhetorical devices the text uses. Don’t feel that you have to cram in every rhetorical term you know—focus on those that are most important to the text.

The following sections show how to write the different parts of a rhetorical analysis.

Like all essays, a rhetorical analysis begins with an introduction . The introduction tells readers what text you’ll be discussing, provides relevant background information, and presents your thesis statement .

Hover over different parts of the example below to see how an introduction works.

Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech is widely regarded as one of the most important pieces of oratory in American history. Delivered in 1963 to thousands of civil rights activists outside the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., the speech has come to symbolize the spirit of the civil rights movement and even to function as a major part of the American national myth. This rhetorical analysis argues that King’s assumption of the prophetic voice, amplified by the historic size of his audience, creates a powerful sense of ethos that has retained its inspirational power over the years.

The body of your rhetorical analysis is where you’ll tackle the text directly. It’s often divided into three paragraphs, although it may be more in a longer essay.

Each paragraph should focus on a different element of the text, and they should all contribute to your overall argument for your thesis statement.

Hover over the example to explore how a typical body paragraph is constructed.

King’s speech is infused with prophetic language throughout. Even before the famous “dream” part of the speech, King’s language consistently strikes a prophetic tone. He refers to the Lincoln Memorial as a “hallowed spot” and speaks of rising “from the dark and desolate valley of segregation” to “make justice a reality for all of God’s children.” The assumption of this prophetic voice constitutes the text’s strongest ethical appeal; after linking himself with political figures like Lincoln and the Founding Fathers, King’s ethos adopts a distinctly religious tone, recalling Biblical prophets and preachers of change from across history. This adds significant force to his words; standing before an audience of hundreds of thousands, he states not just what the future should be, but what it will be: “The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.” This warning is almost apocalyptic in tone, though it concludes with the positive image of the “bright day of justice.” The power of King’s rhetoric thus stems not only from the pathos of his vision of a brighter future, but from the ethos of the prophetic voice he adopts in expressing this vision.

The conclusion of a rhetorical analysis wraps up the essay by restating the main argument and showing how it has been developed by your analysis. It may also try to link the text, and your analysis of it, with broader concerns.

Explore the example below to get a sense of the conclusion.

It is clear from this analysis that the effectiveness of King’s rhetoric stems less from the pathetic appeal of his utopian “dream” than it does from the ethos he carefully constructs to give force to his statements. By framing contemporary upheavals as part of a prophecy whose fulfillment will result in the better future he imagines, King ensures not only the effectiveness of his words in the moment but their continuing resonance today. Even if we have not yet achieved King’s dream, we cannot deny the role his words played in setting us on the path toward it.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

The goal of a rhetorical analysis is to explain the effect a piece of writing or oratory has on its audience, how successful it is, and the devices and appeals it uses to achieve its goals.

Unlike a standard argumentative essay , it’s less about taking a position on the arguments presented, and more about exploring how they are constructed.

The term “text” in a rhetorical analysis essay refers to whatever object you’re analyzing. It’s frequently a piece of writing or a speech, but it doesn’t have to be. For example, you could also treat an advertisement or political cartoon as a text.

Logos appeals to the audience’s reason, building up logical arguments . Ethos appeals to the speaker’s status or authority, making the audience more likely to trust them. Pathos appeals to the emotions, trying to make the audience feel angry or sympathetic, for example.

Collectively, these three appeals are sometimes called the rhetorical triangle . They are central to rhetorical analysis , though a piece of rhetoric might not necessarily use all of them.

In rhetorical analysis , a claim is something the author wants the audience to believe. A support is the evidence or appeal they use to convince the reader to believe the claim. A warrant is the (often implicit) assumption that links the support with the claim.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, July 23). How to Write a Rhetorical Analysis | Key Concepts & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 2, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/rhetorical-analysis/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write an argumentative essay | examples & tips, how to write a literary analysis essay | a step-by-step guide, comparing and contrasting in an essay | tips & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Teaching Rhetorical Analysis: 15 Rhetorical Analysis Questions to Ask Your Students

I love teaching rhetorical analysis. It is one of my favorite units to teach because I love incorporating robust, relevant, and timely texts into my classroom, especially when timely speeches perfectly coincide with the classical literature we are reading. I use this rhetorical analysis unit in my classroom every year, and it helps me provide a solid foundation to my students.

When teaching rhetorical analysis, one of the most important things to keep in mind is not what the author or speaker says, but how the author or speaker says it and why it is so effective. Once you get beyond the main ideas and supporting details and really ask your students to look at, consider, analyze, and evaluate the effectiveness of what the author or speaker does, then you are genuinely analyzing a text for its rhetorical merit.

Teaching Rhetorical Analysis in the Secondary ELA Classroom

When I first teach rhetorical analysis to my students, I use direct instruction strategies. I provide my students with rhetorical analysis terms and examples. Then we begin analyzing and annotating text together. Usually, we will analyze a couple of texts together as a class, and then I release them to work in a small group or with partners. Before I have my students work entirely on their own, I first have them analyze and annotate a text individually for about ten minutes, and then share their findings with a partner. This helps students build their confidence.

If you are teaching rhetorical analysis, here are 15 questions you should ask your students about the text they are reading. These 15 questions are some of the questions included in my Rhetorical Analysis Task Cards.

15 Rhetorical Analysis Questions to Ask Your Students

- What is the main idea or assertion of the text?

- Explain two different ways in which the author/speaker supports the main idea.

- How does the author/speaker establish ethos in the text?

- How does the author/speaker appeal to reason (logos)?

- How does the author/speaker appeal to emotion (pathos)?

- Is the evidence used to support the argument reliable? Explain.

- How does the tone affect the author/speaker’s credibility?

- What is the tone at the beginning, middle, and end of the text?

- What is one rhetorical device used in the text? Explain it’s effectiveness.

- Identify one example of figurative language used in the text. Explain it’s effectiveness.

- Does the author/speaker reveal any prejudices against people who might disagree? Explain.

- Was the author/speaker effective in achieving the purpose? Explain.

- In your opinion, what is the strongest element/part of the text/argument? Explain and provide evidence and reasoning.

- In your opinion, what is the weakest element/part of the text/argument? Explain and provide evidence and reasoning.

- Do you believe the author/speaker achieved the purpose? Explain your answer and provide evidence and reasoning in your response.

Be sure to also read my blog post about my favorite speeches for rhetorical analysis.

Teaching Rhetorical Analysis with Sticky Notes

This hands-on sticky note rhetorical analysis includes an editable PowerPoint presentation with an entire week of direct instruction for rhetorical analysis, a sample speech to analyze with your students, and materials and writing assignments to use with any speech!

Your students will love these interactive and hands-on close reading organizers and scaffolded writing responses. Students will enjoy using sticky notes in class as they analyze complex speeches and nonfiction texts, and the materials are accessible enough for them to do rhetorical analysis.

This unit includes everything you need to be successful in teaching rhetorical analysis.

Here is what fellow teachers say:

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️ extremely satisfied.

“ I used this resource to supplement my AP Lang. and Comp. class Rhetorical Analysis Unit. It had a lot of resources that were very easy to implement and provided different approaches to the rhetorical analysis essay.”

“ This was so helpful in teaching my students to write a rhetorical analysis– I’ve written plenty in my life, but I don’t know that I was ever formally taught how, and have never had to teach this skill prior to this year. This was great not only for my students to learn, but to help give me a better understanding of process as well!”

“ Kids are always excited whenever they get to use sticky notes, so this resource was a hit with my 11th graders – yes, 11th graders! I highly recommend as it helps students thoroughly dissect and understand the text.”

Here are some rhetorical analysis teaching resources you may like:

- Rhetorical Analysis Mini Flip Book

- Rhetorical Analysis Task Cards

- FREE SOAPStone Organizer

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

What Is a Rhetorical Analysis and How to Write a Great One

Helly Douglas

Do you have to write a rhetorical analysis essay? Fear not! We’re here to explain exactly what rhetorical analysis means, how you should structure your essay, and give you some essential “dos and don’ts.”

What is a Rhetorical Analysis Essay?

How do you write a rhetorical analysis, what are the three rhetorical strategies, what are the five rhetorical situations, how to plan a rhetorical analysis essay, creating a rhetorical analysis essay, examples of great rhetorical analysis essays, final thoughts.

A rhetorical analysis essay studies how writers and speakers have used words to influence their audience. Think less about the words the author has used and more about the techniques they employ, their goals, and the effect this has on the audience.

In your analysis essay, you break a piece of text (including cartoons, adverts, and speeches) into sections and explain how each part works to persuade, inform, or entertain. You’ll explore the effectiveness of the techniques used, how the argument has been constructed, and give examples from the text.

A strong rhetorical analysis evaluates a text rather than just describes the techniques used. You don’t include whether you personally agree or disagree with the argument.

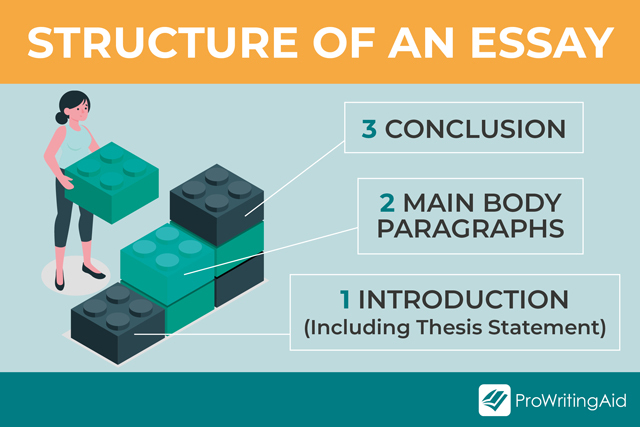

Structure a rhetorical analysis in the same way as most other types of academic essays . You’ll have an introduction to present your thesis, a main body where you analyze the text, which then leads to a conclusion.

Think about how the writer (also known as a rhetor) considers the situation that frames their communication:

- Topic: the overall purpose of the rhetoric

- Audience: this includes primary, secondary, and tertiary audiences

- Purpose: there are often more than one to consider

- Context and culture: the wider situation within which the rhetoric is placed

Back in the 4th century BC, Aristotle was talking about how language can be used as a means of persuasion. He described three principal forms —Ethos, Logos, and Pathos—often referred to as the Rhetorical Triangle . These persuasive techniques are still used today.

Rhetorical Strategy 1: Ethos

Are you more likely to buy a car from an established company that’s been an important part of your community for 50 years, or someone new who just started their business?

Reputation matters. Ethos explores how the character, disposition, and fundamental values of the author create appeal, along with their expertise and knowledge in the subject area.

Aristotle breaks ethos down into three further categories:

- Phronesis: skills and practical wisdom

- Arete: virtue

- Eunoia: goodwill towards the audience

Ethos-driven speeches and text rely on the reputation of the author. In your analysis, you can look at how the writer establishes ethos through both direct and indirect means.

Rhetorical Strategy 2: Pathos

Pathos-driven rhetoric hooks into our emotions. You’ll often see it used in advertisements, particularly by charities wanting you to donate money towards an appeal.

Common use of pathos includes:

- Vivid description so the reader can imagine themselves in the situation

- Personal stories to create feelings of empathy

- Emotional vocabulary that evokes a response

By using pathos to make the audience feel a particular emotion, the author can persuade them that the argument they’re making is compelling.

Rhetorical Strategy 3: Logos

Logos uses logic or reason. It’s commonly used in academic writing when arguments are created using evidence and reasoning rather than an emotional response. It’s constructed in a step-by-step approach that builds methodically to create a powerful effect upon the reader.

Rhetoric can use any one of these three techniques, but effective arguments often appeal to all three elements.

The rhetorical situation explains the circumstances behind and around a piece of rhetoric. It helps you think about why a text exists, its purpose, and how it’s carried out.

The rhetorical situations are:

- 1) Purpose: Why is this being written? (It could be trying to inform, persuade, instruct, or entertain.)

- 2) Audience: Which groups or individuals will read and take action (or have done so in the past)?

- 3) Genre: What type of writing is this?

- 4) Stance: What is the tone of the text? What position are they taking?

- 5) Media/Visuals: What means of communication are used?

Understanding and analyzing the rhetorical situation is essential for building a strong essay. Also think about any rhetoric restraints on the text, such as beliefs, attitudes, and traditions that could affect the author's decisions.

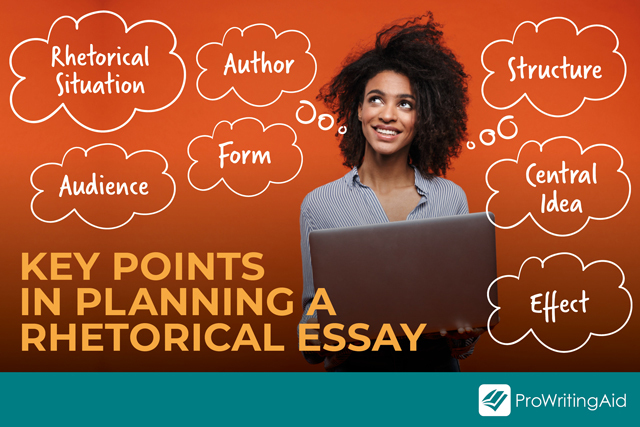

Before leaping into your essay, it’s worth taking time to explore the text at a deeper level and considering the rhetorical situations we looked at before. Throw away your assumptions and use these simple questions to help you unpick how and why the text is having an effect on the audience.

1: What is the Rhetorical Situation?

- Why is there a need or opportunity for persuasion?

- How do words and references help you identify the time and location?

- What are the rhetoric restraints?

- What historical occasions would lead to this text being created?

2: Who is the Author?

- How do they position themselves as an expert worth listening to?

- What is their ethos?

- Do they have a reputation that gives them authority?

- What is their intention?

- What values or customs do they have?

3: Who is it Written For?

- Who is the intended audience?

- How is this appealing to this particular audience?

- Who are the possible secondary and tertiary audiences?

4: What is the Central Idea?

- Can you summarize the key point of this rhetoric?

- What arguments are used?

- How has it developed a line of reasoning?

5: How is it Structured?

- What structure is used?

- How is the content arranged within the structure?

6: What Form is Used?

- Does this follow a specific literary genre?

- What type of style and tone is used, and why is this?

- Does the form used complement the content?

- What effect could this form have on the audience?

7: Is the Rhetoric Effective?

- Does the content fulfil the author’s intentions?

- Does the message effectively fit the audience, location, and time period?

Once you’ve fully explored the text, you’ll have a better understanding of the impact it’s having on the audience and feel more confident about writing your essay outline.

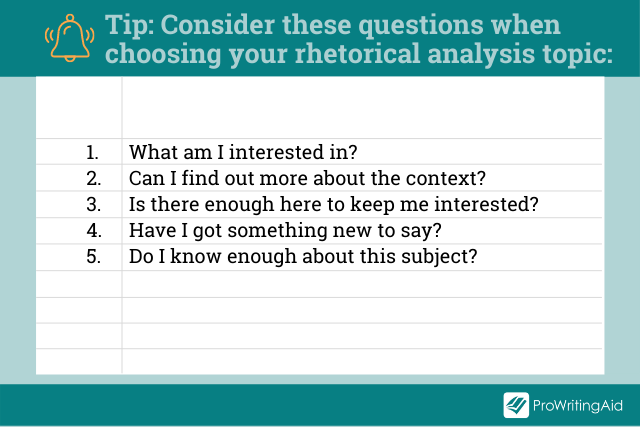

A great essay starts with an interesting topic. Choose carefully so you’re personally invested in the subject and familiar with it rather than just following trending topics. There are lots of great ideas on this blog post by My Perfect Words if you need some inspiration. Take some time to do background research to ensure your topic offers good analysis opportunities.

Remember to check the information given to you by your professor so you follow their preferred style guidelines. This outline example gives you a general idea of a format to follow, but there will likely be specific requests about layout and content in your course handbook. It’s always worth asking your institution if you’re unsure.

Make notes for each section of your essay before you write. This makes it easy for you to write a well-structured text that flows naturally to a conclusion. You will develop each note into a paragraph. Look at this example by College Essay for useful ideas about the structure.

1: Introduction

This is a short, informative section that shows you understand the purpose of the text. It tempts the reader to find out more by mentioning what will come in the main body of your essay.

- Name the author of the text and the title of their work followed by the date in parentheses

- Use a verb to describe what the author does, e.g. “implies,” “asserts,” or “claims”

- Briefly summarize the text in your own words

- Mention the persuasive techniques used by the rhetor and its effect

Create a thesis statement to come at the end of your introduction.

After your introduction, move on to your critical analysis. This is the principal part of your essay.

- Explain the methods used by the author to inform, entertain, and/or persuade the audience using Aristotle's rhetorical triangle

- Use quotations to prove the statements you make

- Explain why the writer used this approach and how successful it is

- Consider how it makes the audience feel and react

Make each strategy a new paragraph rather than cramming them together, and always use proper citations. Check back to your course handbook if you’re unsure which citation style is preferred.

3: Conclusion

Your conclusion should summarize the points you’ve made in the main body of your essay. While you will draw the points together, this is not the place to introduce new information you’ve not previously mentioned.

Use your last sentence to share a powerful concluding statement that talks about the impact the text has on the audience(s) and wider society. How have its strategies helped to shape history?

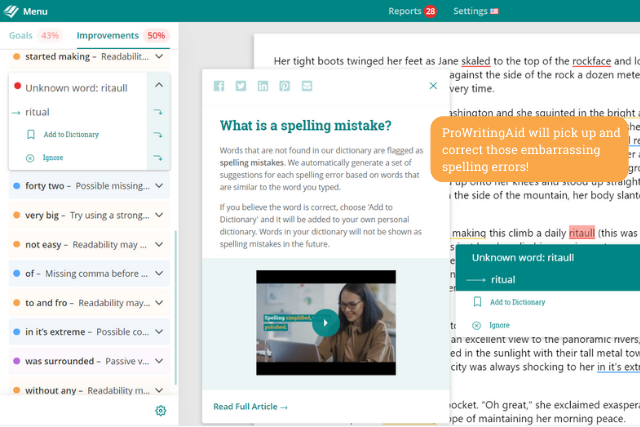

Before You Submit

Poor spelling and grammatical errors ruin a great essay. Use ProWritingAid to check through your finished essay before you submit. It will pick up all the minor errors you’ve missed and help you give your essay a final polish. Look at this useful ProWritingAid webinar for further ideas to help you significantly improve your essays. Sign up for a free trial today and start editing your essays!

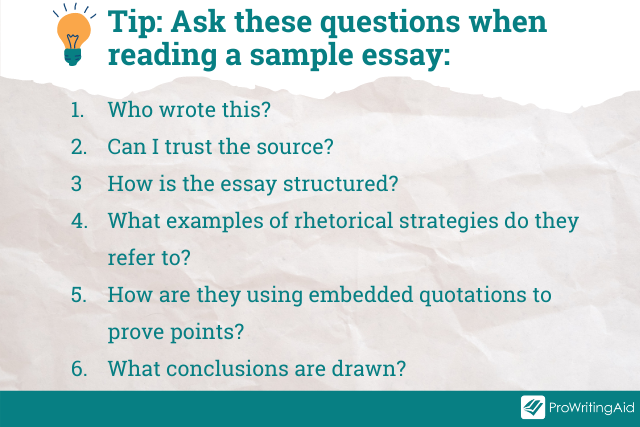

You’ll find countless examples of rhetorical analysis online, but they range widely in quality. Your institution may have example essays they can share with you to show you exactly what they’re looking for.

The following links should give you a good starting point if you’re looking for ideas:

Pearson Canada has a range of good examples. Look at how embedded quotations are used to prove the points being made. The end questions help you unpick how successful each essay is.

Excelsior College has an excellent sample essay complete with useful comments highlighting the techniques used.

Brighton Online has a selection of interesting essays to look at. In this specific example, consider how wider reading has deepened the exploration of the text.

Writing a rhetorical analysis essay can seem daunting, but spending significant time deeply analyzing the text before you write will make it far more achievable and result in a better-quality essay overall.

It can take some time to write a good essay. Aim to complete it well before the deadline so you don’t feel rushed. Use ProWritingAid’s comprehensive checks to find any errors and make changes to improve readability. Then you’ll be ready to submit your finished essay, knowing it’s as good as you can possibly make it.

Try ProWritingAid's Editor for Yourself

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Helly Douglas is a UK writer and teacher, specialising in education, children, and parenting. She loves making the complex seem simple through blogs, articles, and curriculum content. You can check out her work at hellydouglas.com or connect on Twitter @hellydouglas. When she’s not writing, you will find her in a classroom, being a mum or battling against the wilderness of her garden—the garden is winning!

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to write a rhetorical analysis

What is a rhetorical analysis?

What are the key concepts of a rhetorical analysis, rhetorical situation, claims, supports, and warrants.

- Step 1: Plan and prepare

- Step 2: Write your introduction

- Step 3: Write the body

- Step 4: Write your conclusion

Frequently Asked Questions about rhetorical analysis

Related articles.

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion and aims to study writers’ or speakers' techniques to inform, persuade, or motivate their audience. Thus, a rhetorical analysis aims to explore the goals and motivations of an author, the techniques they’ve used to reach their audience, and how successful these techniques were.

This will generally involve analyzing a specific text and considering the following aspects to connect the rhetorical situation to the text:

- Does the author successfully support the thesis or claims made in the text? Here, you’ll analyze whether the author holds to their argument consistently throughout the text or whether they wander off-topic at some point.

- Does the author use evidence effectively considering the text’s intended audience? Here, you’ll consider the evidence used by the author to support their claims and whether the evidence resonates with the intended audience.

- What rhetorical strategies the author uses to achieve their goals. Here, you’ll consider the word choices by the author and whether these word choices align with their agenda for the text.

- The tone of the piece. Here, you’ll consider the tone used by the author in writing the piece by looking at specific words and aspects that set the tone.

- Whether the author is objective or trying to convince the audience of a particular viewpoint. When it comes to objectivity, you’ll consider whether the author is objective or holds a particular viewpoint they want to convince the audience of. If they are, you’ll also consider whether their persuasion interferes with how the text is read and understood.

- Does the author correctly identify the intended audience? It’s important to consider whether the author correctly writes the text for the intended audience and what assumptions the author makes about the audience.

- Does the text make sense? Here, you’ll consider whether the author effectively reasons, based on the evidence, to arrive at the text’s conclusion.

- Does the author try to appeal to the audience’s emotions? You’ll need to consider whether the author uses any words, ideas, or techniques to appeal to the audience’s emotions.

- Can the author be believed? Finally, you’ll consider whether the audience will accept the arguments and ideas of the author and why.

Summing up, unlike summaries that focus on what an author said, a rhetorical analysis focuses on how it’s said, and it doesn’t rely on an analysis of whether the author was right or wrong but rather how they made their case to arrive at their conclusions.

Although rhetorical analysis is most used by academics as part of scholarly work, it can be used to analyze any text including speeches, novels, television shows or films, advertisements, or cartoons.

Now that we’ve seen what rhetorical analysis is, let’s consider some of its key concepts .

Any rhetorical analysis starts with the rhetorical situation which identifies the relationships between the different elements of the text. These elements include the audience, author or writer, the author’s purpose, the delivery method or medium, and the content:

- Audience: The audience is simply the readers of a specific piece of text or content or printed material. For speeches or other mediums like film and video, the audience would be the listeners or viewers. Depending on the specific piece of text or the author’s perception, the audience might be real, imagined, or invoked. With a real audience, the author writes to the people actually reading or listening to the content while, for an imaginary audience, the author writes to an audience they imagine would read the content. Similarly, for an invoked audience, the author writes explicitly to a specific audience.

- Author or writer: The author or writer, also commonly referred to as the rhetor in the context of rhetorical analysis, is the person or the group of persons who authored the text or content.

- The author’s purpose: The author’s purpose is the author’s reason for communicating to the audience. In other words, the author’s purpose encompasses what the author expects or intends to achieve with the text or content.

- Alphabetic text includes essays, editorials, articles, speeches, and other written pieces.

- Imaging includes website and magazine advertisements, TV commercials, and the like.

- Audio includes speeches, website advertisements, radio or tv commercials, or podcasts.

- Context: The context of the text or content considers the time, place, and circumstances surrounding the delivery of the text to its audience. With respect to context, it might often also be helpful to analyze the text in a different context to determine its impact on a different audience and in different circumstances.

An author will use claims, supports, and warrants to build the case around their argument, irrespective of whether the argument is logical and clearly defined or needs to be inferred by the audience:

- Claim: The claim is the main idea or opinion of an argument that the author must prove to the intended audience. In other words, the claim is the fact or facts the author wants to convince the audience of. Claims are usually explicitly stated but can, depending on the specific piece of content or text, be implied from the content. Although these claims could be anything and an argument may be based on a single or several claims, the key is that these claims should be debatable.

- Support: The supports are used by the author to back up the claims they make in their argument. These supports can include anything from fact-based, objective evidence to subjective emotional appeals and personal experiences used by the author to convince the audience of a specific claim. Either way, the stronger and more reliable the supports, the more likely the audience will be to accept the claim.

- Warrant: The warrants are the logic and assumptions that connect the supports to the claims. In other words, they’re the assumptions that make the initial claim possible. The warrant is often unstated, and the author assumes that the audience will be able to understand the connection between the claims and supports. In turn, this is based on the author’s assumption that they share a set of values and beliefs with the audience that will make them understand the connection mentioned above. Conversely, if the audience doesn’t share these beliefs and values with the author, the argument will not be that effective.

Appeals are used by authors to convince their audience and, as such, are an integral part of the rhetoric and are often referred to as the rhetorical triangle. As a result, an author may combine all three appeals to convince their audience:

- Ethos: Ethos represents the authority or credibility of the author. To be successful, the author needs to convince the audience of their authority or credibility through the language and delivery techniques they use. This will, for example, be the case where an author writing on a technical subject positions themselves as an expert or authority by referring to their qualifications or experience.

- Logos: Logos refers to the reasoned argument the author uses to persuade their audience. In other words, it refers to the reasons or evidence the author proffers in substantiation of their claims and can include facts, statistics, and other forms of evidence. For this reason, logos is also the dominant approach in academic writing where authors present and build up arguments using reasoning and evidence.

- Pathos: Through pathos, also referred to as the pathetic appeal, the author attempts to evoke the audience’s emotions through the use of, for instance, passionate language, vivid imagery, anger, sympathy, or any other emotional response.

To write a rhetorical analysis, you need to follow the steps below:

With a rhetorical analysis, you don’t choose concepts in advance and apply them to a specific text or piece of content. Rather, you’ll have to analyze the text to identify the separate components and plan and prepare your analysis accordingly.

Here, it might be helpful to use the SOAPSTone technique to identify the components of the work. SOAPSTone is a common acronym in analysis and represents the:

- Speaker . Here, you’ll identify the author or the narrator delivering the content to the audience.

- Occasion . With the occasion, you’ll identify when and where the story takes place and what the surrounding context is.

- Audience . Here, you’ll identify who the audience or intended audience is.

- Purpose . With the purpose, you’ll need to identify the reason behind the text or what the author wants to achieve with their writing.

- Subject . You’ll also need to identify the subject matter or topic of the text.

- Tone . The tone identifies the author’s feelings towards the subject matter or topic.

Apart from gathering the information and analyzing the components mentioned above, you’ll also need to examine the appeals the author uses in writing the text and attempting to persuade the audience of their argument. Moreover, you’ll need to identify elements like word choice, word order, repetition, analogies, and imagery the writer uses to get a reaction from the audience.

Once you’ve gathered the information and examined the appeals and strategies used by the author as mentioned above, you’ll need to answer some questions relating to the information you’ve collected from the text. The answers to these questions will help you determine the reasons for the choices the author made and how well these choices support the overall argument.

Here, some of the questions you’ll ask include:

- What was the author’s intention?

- Who was the intended audience?

- What is the author’s argument?

- What strategies does the author use to build their argument and why do they use those strategies?

- What appeals the author uses to convince and persuade the audience?

- What effect the text has on the audience?

Keep in mind that these are just some of the questions you’ll ask, and depending on the specific text, there might be others.

Once you’ve done your preparation, you can start writing the rhetorical analysis. It will start off with an introduction which is a clear and concise paragraph that shows you understand the purpose of the text and gives more information about the author and the relevance of the text.

The introduction also summarizes the text and the main ideas you’ll discuss in your analysis. Most importantly, however, is your thesis statement . This statement should be one sentence at the end of the introduction that summarizes your argument and tempts your audience to read on and find out more about it.

After your introduction, you can proceed with the body of your analysis. Here, you’ll write at least three paragraphs that explain the strategies and techniques used by the author to convince and persuade the audience, the reasons why the writer used this approach, and why it’s either successful or unsuccessful.

You can structure the body of your analysis in several ways. For example, you can deal with every strategy the author uses in a new paragraph, but you can also structure the body around the specific appeals the author used or chronologically.

No matter how you structure the body and your paragraphs, it’s important to remember that you support each one of your arguments with facts, data, examples, or quotes and that, at the end of every paragraph, you tie the topic back to your original thesis.

Finally, you’ll write the conclusion of your rhetorical analysis. Here, you’ll repeat your thesis statement and summarize the points you’ve made in the body of your analysis. Ultimately, the goal of the conclusion is to pull the points of your analysis together so you should be careful to not raise any new issues in your conclusion.

After you’ve finished your conclusion, you’ll end your analysis with a powerful concluding statement of why your argument matters and an invitation to conduct more research if needed.

A rhetorical analysis aims to explore the goals and motivations of an author, the techniques they’ve used to reach their audience, and how successful these techniques were. Although rhetorical analysis is most used by academics as part of scholarly work, it can be used to analyze any text including speeches, novels, television shows or films, advertisements, or cartoons.

The steps to write a rhetorical analysis include:

Your rhetorical analysis introduction is a clear and concise paragraph that shows you understand the purpose of the text and gives more information about the author and the relevance of the text. The introduction also summarizes the text and the main ideas you’ll discuss in your analysis.

Ethos represents the authority or credibility of the author. To be successful, the author needs to convince the audience of their authority or credibility through the language and delivery techniques they use. This will, for example, be the case where an author writing on a technical subject positions themselves as an expert or authority by referring to their qualifications or experience.

Appeals are used by authors to convince their audience and, as such, are an integral part of the rhetoric and are often referred to as the rhetorical triangle. The 3 types of appeals are ethos, logos, and pathos.

Teaching Rhetorical Analysis

Main navigation.

As the first assignment in our common curriculum, the rhetorical analysis provides students with not only an entryway into the class, but an introduction to foundational concepts of rhetoric, reading, and writing that will inform their work during the quarter. Below are some considerations to keep in mind as you design the assignment.

Designing the Assignment

Some of the first questions you need to answer for yourself as you start to design the assignment have to do with how to create an assignment consistent with the learning objectives for the Rhetorical Analysis, and what texts -- and what types of texts -- students will analyze. For the rhetorical analysis, it's best to have students focus on a single text rather than write a comparative analysis. Consider the following questions:

- choose texts that you know will yield interest discussion concerning rhetoric

- limit the array of choices so that you and the students can read multiple essays on the same texts (which helps with peer review and students working through their ideas together)

- avoid having to arrive at a rhetorical understanding of 15 unique objects.

The disadvantage of you choosing is that you limit student choice. Many instructors opt for a hybrid model: they provide a short menu of possible texts the students could write on, but also allow student choice (with instructor approval)

- Think about relationship to other assignments - how much time do you want to devote to the RA assignment? Most lecturers have a draft due at the end of week two or beginning of week three. In this case, the goal would be for students to start working on their second assignment (the Texts in Conversation) by week 4.

- What texts/objects will you select or can a student choose among for their analysis? What will guide your choice or should guide their choice? A PWR Rhetorical analysis may focus on a written, visual, audio, or multimedia text. See samples of Rhetorical analysis assignment sheets , grouped by genre.

Presenting the Assignment to Students

Since the rhetorical analysis essay is a specific academic genre, it might be helpful to indicate some of the typical features of the genre and the role it plays in the broader field of rhetoric.

Think about how to help students see that it’s different from just writing on a short story or novel as they’ve done in English class, focused more on the “how” and “why” of what a text says than on the “what.” They might assume that it's just like an analysis of a literary text; we need to help them see how it's different.

Think about how to help students see how rhetorical analysis informs their own drafting and revision process, particular as they develop more awareness of the interaction between audience and purpose shaping their composing process

Think about the fact that some students (but only some) have taken APLang, a class in which they are introduced to rhetorical analysis, often through an emphasis on the classical rhetorical appeals.

Scaffolding the Assignment with Class Activities and Prewriting

You should carefully scaffold the rhetorical analysis assignment through a range of low-stakes, ungraded activities designed to help students practice and develop some of the strategies they'll use in writing their essays. These activities should also help them understand that the writing the do for the assignment begins even before they start their first draft.

What kinds of guiding questions can students analyze their texts? If there is pre-writing, will you look at it, or will they share it with classmates?

How will you talk about the relationship between brainstorming and prewriting exercises and planning the essay itself?

Will you give them samples of past rhetorical analyses? Will you want to discuss them in class or just make them available to students as a reference?

See some scaffolding activities for the Rhetorical Analysis through our class activity archive

Designing Peer Review for the Rhetorical Analysis

This is likely to be one of their first experiences with peer review at Stanford, so you may want to think about how you want them to understand and value the process. Often, students come in the door with negative or mixed experiences of peer review, so it may be a good idea to start with their experience of peer review: what worked, what didn’t, to establish group expectations.

Some students are uncertain of their ability to give helpful feedback. How can you define the reviewer role in a way that helps students see the value of their responses as readers?

How structured do you want to make their peer review (very structured with assigned roles and specific questions provided by you or less structured based on the interests of the writers and reviewers)?

Will the students read the essays outside of class or during class? Keep in mind that many students prefer advanced preparation, since reading on the spot may disadvantage students who read more slowly and/or have learning or cognitive differences that may make reading and then responding immediately difficult.

Do you expect them to provide written comments or oral feedback or both?

Do you want to see any of their written comments?

Do you want students to reflect on and report back about the feedback they received and their developing plans for revision?

How can you signal the connection between peer review and the evaluation criteria that you’ll use for providing your own feedback on their draft?

See further advice and activities about designing effective peer feedback sessions

There is no requirement in PWR 1 to have a reflection component attached to any of the assignments; however, since we recognize the value of metacognition for student growth as writers, almost all instructors have students perform a self-assessment, write a cover memo for their essay, or otherwise write a reflection as a culminating moment in completing the essay.

Reflection on their writing process may be new for students, and it may be important to make explicit to them what the value of reflection is for their growth as writers, and the role it plays (or doesn’t play) in your assessment of their work.

Given the role the rhetorical analysis plays in their development as writers, what aspects of the drafting and revising process do you want them to focus on in their reflections?

You might consider using the RA reflection to encourage students to look forward as well as back, or to connect to their broader experience of writers in other ways.

Assessing the Assignment

The evaluation criteria that you develop for your rhetorical analysis assignment should be clear, available to the students during their drafting phase (although drafts themselves should not be graded), and should retain a focus on formative feedback as much as summative assessment. Always make sure the evaluation criteria you develop links directly to your learning objectives for the assignment.

Think about how to create a rubric that will be in dialogue with the other assignment rubrics. Many instructors have a single rubric that they use across the different assignments that they simple gently customize with language to fit the particulars of each assignment.

Consider using the rubric to organize your feedback on drafts so that students understand the relationship between your suggestions and the evaluation criteria for the assignment.

Use caution if adopting a numerical scale which might lead you to arbitrary quantification of elements of the essay.

Will students use the rubric in peer review? How will you teach them to use the rubric to inform the feedback they give?

Look at Bean's " Using Rubrics " chapter from Engaging Ideas to help you design your own effective grading rubric

- Rhetorical Question

Rhetorical Question Definition

What is a rhetorical question? Here’s a quick and simple definition:

A rhetorical question is a figure of speech in which a question is asked for a reason other than to get an answer—most commonly, it's asked to make a persuasive point. For example, if a person asks, "How many times do I have to tell you not to eat my dessert?" he or she does not want to know the exact number of times the request will need to be repeated. Rather, the speaker's goal is to emphasize his or her growing frustration and—ideally—change the dessert-thief's behavior.

Some additional key details about rhetorical questions:

- Rhetorical questions are also sometimes called erotema.

- Rhetorical questions are a type of figurative language —they are questions that have another layer of meaning on top of their literal meaning.

- Because rhetorical questions challenge the listener, raise doubt, and help emphasize ideas, they appear often in songs and speeches, as well as in literature.

How to Pronounce Rhetorical Question

Here's how to pronounce rhetorical question: reh- tor -ih-kuhl kwes -chun

Rhetorical Questions and Punctuation

A question is rhetorical if and only if its goal is to produce an effect on the listener, rather than to obtain information. In other words, a rhetorical question is not what we might call a "true" question in search of an answer. For this reason, many sources argue that rhetorical questions do not need to end in a traditional question mark. In the late 1500's, English printer Henry Denham actually designed a special question mark for rhetorical questions, which he referred to as a "percontation point." It looked like this: ⸮ (Here's a wikipedia article about Denham's percontation point and other forms of "irony punctuation.")

Though the percontation point has fallen out of use, modern writers do sometimes substitute a traditional question mark with a period or exclamation point after a rhetorical question. There is a lively debate as to whether this alternative punctuation is grammatically correct. Here are some guidelines to follow:

- In general, rhetorical questions do require a question mark.

- When a question is a request in disguise, you may use a period. For instance, it is ok to write: "Will you please turn your attention to the speaker." or "Can you please go to the back of the line."

- When a question is an exclamation in disguise, you may use an exclamation point. For instance, it is okay to write: "Were they ever surprised!"

- When asking a question emotionally, you may use an exclamation point. For instance, " Who could blame him!" and "How do you know that!" are both correct.

Rhetorical Questions vs. Hypophora

Rhetorical questions are easy to confuse with hypophora , a similar but fundamentally different figure of speech in which a speaker poses a question and then immediately answers it. Hypophora is frequently used in persuasive speaking because the speaker can pose and answer a question that the audience is likely to be wondering about, thereby making the thought processes of the speaker and the audience seem more aligned. For example, here is an example of hypophora used in a speech by Dwight Eisenhower:

When the enemy struck on that June day of 1950, what did America do? It did what it always has done in all its times of peril. It appealed to the heroism of its youth.

While Eisenhower asked this question without expecting an answer from his audience, this is an example of hypophora because he answered his own question. In a rhetorical question, by contrast, the answer would be implied in the question—to pose a rhetorical question, Eisenhower might have said instead, "When the enemy struck, who in their right mind would have done nothing to retaliate?"

Rhetorical Questions vs. Aporia

Rhetorical questions are also related to a figure of speech called aporia . Aporia is an expression of doubt that may be real, or which may be feigned for rhetorical effect. These expressions of doubt may or may not be made through the form of a question. When they are made through the form of a question, those questions are sometimes rhetorical.

Aporia and Rhetorical Questions

When someone is pretending doubt for rhetorical effect, and uses a question as part of that expression of doubt, then the question is rhetorical. For example, consider this quotation from an oration by the ancient Greek orator Demosthenes:

I am at no loss for information about you and your family; but I am at a loss where to begin. Shall I relate how your father Tromes was a slave in the house of Elpias, who kept an elementary school near the Temple of Theseus, and how he wore shackles on his legs and a timber collar round his neck? Or how your mother practised daylight nuptials in an outhouse next door to Heros the bone-setter, and so brought you up to act in tableaux vivants and to excel in minor parts on the stage?

The questions Demosthenes poses are examples of both aporia and rhetorical question, because Demosthenes is feigning doubt (by posing rhetorical questions) in order to cast insulting aspersions on the character of the person he's addressing.

Aporia Without Rhetorical Questions

If the expression of doubt is earnest, however, then the question is not rhetorical. An example of aporia that is not also a rhetorical question comes from the most famous excerpt of Shakespeare's Hamlet:

To be or not to be—that is the question. Whether ‘tis nobler in the mind to suffer The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, Or to take arms against a sea of troubles, And by opposing end them?

While Hamlet asks this question without expecting an answer (he's alone when he asks it), he's not asking in order to persuade or make a point. It's a legitimate expression of doubt, which leads Hamlet into a philosophical debate about whether one should face the expected miseries of life or kill oneself and face the possible unknown terrors of death. It's therefore not a rhetorical question, because Hamlet asks the question as an opening to actually seek an answer to the question he is obsessing over.

Rhetorical Question Examples

Rhetorical question examples in literature.

Rhetorical questions are particularly common in plays, appearing frequently in both spoken dialogue between characters, and in monologues or soliloquies, where they allow the playwright to reveal a character's inner life.

Rhetorical Questions in Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice :

In his speech from Act 3, Scene 1 of Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice , Shylock uses rhetorical questions to point out the indisputable similarities between Jews and Christians, in such a way that any listener would find him impossible to contradict:

I am a Jew. Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions? fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer, as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? if you tickle us, do we not laugh? if you poison us, do we not die? and if you wrong us, shall we not revenge? If we are like you in the rest, we will resemble you in that. If a Jew wrong a Christian, what is his humility? Revenge. If a Christian wrong a Jew, what should his sufferance be by Christian example? Why, revenge. The villainy you teach me, I will execute, and it shall go hard but I will better the instruction.

Rhetorical questions in Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet :

In this soliloquy from Act 2, Scene 2 of Romeo and Juliet , Juliet poses a series of rhetorical questions as she struggles to grasp the difficult truth—that her beloved Romeo is a member of the Montague family:

Thou art thyself, though not a Montague. What's Montague? it is nor hand, nor foot, Nor arm, nor face, nor any other part Belonging to a man. O, be some other name! What's in a name? that which we call a rose By any other name would smell as sweet; So Romeo would, were he not Romeo call'd Retain that dear perfection which he owes Without that title. Romeo, doff thy name, And for that name which is no part of thee Take all myself.

Rhetorical Question Examples in Political Speeches

Rhetorical questions often "challenge" the listener to contradict what the speaker is saying. If the speaker frames the rhetorical question well, it gives the impression that his or her view is true and that it would be foolish, or even impossible, to contradict the speaker's argument. In other words, rhetorical questions are great for speeches.

Rhetorical Questions in Ronald Reagan's 1980 Republican National Convention Acceptance Address:

In this speech, Reagan uses a series of rhetorical questions—referred to as "stacked" rhetorical questions—to criticize the presidency of his predecessor and running opponent, Jimmy Carter:

Can anyone look at the record of this Administration and say, "Well done"? Can anyone compare the state of our economy when the Carter Administration took office with where we are today and say, "Keep up the good work"? Can anyone look at our reduced standing in the world today say, "Let's have four more years of this"?

Rhetorical Questions in Hillary Clinton's 2016 Democratic National Convention Speech:

In this portion of her speech, Clinton argues that her opponent Donald Trump is not temperamentally fit to become president:

A president should respect the men and women who risk their lives to serve our country—including Captain Khan and the sons of Tim Kaine and Mike Pence, both Marines. So just ask yourself: Do you really think Donald Trump has the temperament to be commander-in-chief?

Rhetorical Question Examples in Song Lyrics

Love has left even the best musicians of our time feeling lost, searching for meaning, and—as you might expect—full of rhetorical questions. Musicians such as Tina Turner, Jean Knight, and Stevie Wonder have all released hits structured around rhetorical questions, which allow them to powerfully express the joy, the pain, and the mystery of L-O-V-E.

Rhetorical Questions in "What's Love Got to do with It" by Tina Turner

What's love got to do, got to do with it What's love but a second hand emotion What's love got to do, got to do with it Who needs a heart when a heart can be broken

Rhetorical Questions in "Mr. Big Stuff" by Jean Knight

Now because you wear all those fancy clothes (oh yeah) And have a big fine car, oh yes you do now Do you think I can afford to give you my love (oh yeah) You think you're higher than every star above

Mr. Big Stuff Who do you think you are Mr. Big Stuff You're never gonna get my love

Rhetorical Questions in "Isn't She Lovely" by Stevie Wonder

Isn't she lovely Isn't she wonderful Isn't she precious Less than one minute old I never thought through love we'd be Making one as lovely as she But isn't she lovely made from love

Stevie Wonder wrote "Isn't She Lovely" to celebrate the birth of his daughter, Aisha. The title is a perfect example of a rhetorical question, because Wonder isn't seeking a second opinion here. Instead, the question is meant to convey the love and amazement he feels towards his daughter.

Why Do Writers Use Rhetorical Questions?

Authors, playwrights, speech writers and musicians use rhetorical questions for a variety of reasons:

- To challenge the listener

- To emphasize an idea

- To raise doubt

- To demonstrate that a previously asked question was obvious

The examples included in this guide to rhetorical questions have largely pointed to the persuasive power of rhetorical questions, and covered the way that they are used in arguments, both real and fictional. However, poets also frequently use rhetorical questions for their lyrical, expressive qualities. Take the poem below, "Danse Russe (Russian Dance)" by William Carlos Williams:

If when my wife is sleeping and the baby and Kathleen are sleeping and the sun is a flame-white disc in silken mists above shining trees,— if I in my north room dance naked, grotesquely before my mirror waving my shirt round my head and singing softly to myself: "I am lonely, lonely. I was born to be lonely. I am best so!" If I admire my arms, my face, my shoulders, flanks, buttocks against the yellow drawn shades,— Who shall say I am not the happy genius of my household?

The rhetorical question that concludes this poem has the effect of challenging the reader to doubt Williams' happiness—daring the listener to question this intimate, eccentric portrait of the poet's private world. By ending the poem in this way, Williams maintains a delicate balance. Throughout the poem, he draws the reader in and confides secrets of his interior life, but the question at the end is an almost defiant statement that he does not require the reader's approval. Rather, the reader—like the mirror—is simply there to witness his happy solitude.

Other Helpful Rhetorical Question Resources

- The Wikipedia Page on Rhetorical Questions: A general explanation with a variety of examples, as well as links to specific resources with punctuation rules.

- The Dictionary Definition of Rhetorical Question: A basic definition with some historical information.

- A detailed explanation of rhetorical questions , along with related figures of speech that involve questions.

- A video of Ronald Reagan's 1980 Republican National Convention Speech, in which he asks stacked rhetorical questions.

- An article listing the greatest rhetorical questions in the history of pop music.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1899 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 39,983 quotes across 1899 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

- Figurative Language

- Figure of Speech

- Climax (Figure of Speech)

- End-Stopped Line

- Anadiplosis

- Internal Rhyme

- Stream of Consciousness

- Round Character

- Connotation

- Verbal Irony

English 110: Critical Thinking About the Politics of Language

Instructor: Anna Alexis Larsson

Questions for Rhetorical Analysis

Conducting a rhetorical analysis asks you to bring to bear on an argument your knowledge of argument and your repertoire of reading strategies. The chart of questions for analysis below (1 – 10) can help you examine an argument in depth. Although a rhetorical analysis will not include answers to all of these questions, using some of these questions in your thinking stages can give you a thorough understanding of the argument while helping you generate insights for your own rhetorical analysis essay.

What to Focus On: The kairotic moment and writer’s motivating occasion Questions to Ask ■ What motivated the writer to produce this piece? ■ What social, cultural, political, legal, or economic conversations does this argument join? Applying These Questions ■ Is the writer responding to a bill pending in Congress, a speech by a political leader, or a local event that provoked controversy? ■ Is the writer addressing cultural trends such as the impact of science or technology on values?

What to Focus On: Rhetorical context: Writer’s purpose and audience Questions to Ask ■ What is the writer’s purpose? ■ Who is the intended audience? ■ What assumptions, values, and beliefs would readers have to hold to find this argument persuasive? ■ How well does the text suit its particular audience and purpose? Applying These Questions ■ Is the writer trying to change readers’ views by offering a new interpretation of a phenomenon, calling readers to action, or trying to muster votes or inspire further investigations? ■ Does the audience share a political or religious orientation with the writer?

What to Focus On: The kairotic moment and writer’s motivating occasion

Questions to Ask ■ What motivated the writer to produce this piece? ■ What social, cultural, political, legal, or economic conversations does this argument join?

Applying These Questions ■ Is the writer responding to a bill pending in Congress, a speech by a political leader, or a local event that provoked controversy? ■ Is the writer addressing cultural trends such as the impact of science or technology on values?

What to Focus On: Rhetorical context: Writer’s purpose and audience

Questions to Ask ■ What is the writer’s purpose? ■ Who is the intended audience? ■ What assumptions, values, and beliefs would readers have to hold to find this argument persuasive? ■ How well does the text suit its particular audience and purpose?

Applying These Questions ■ Is the writer trying to change readers’ views by offering a new interpretation of a phenomenon, calling readers to action, or trying to muster votes or inspire further investigations? ■ Does the audience share a political or religious orientation with the writer?

What to Focus On On Rhetorical context: Writer’s identity and angle of vision

Questions to Ask ◊ Who is the writer and what is his or her profession, background, and expertise? ◊ How does the writer’s personal history, education, gender, ethnicity, age, class, sexual orientation, and political leaning influence the angle of vision? ◊ What is emphasized and what is omitted in this text? ◊ How much does the writer’s angle of vision dominate the text?

Applying These Questions ◊ Is the writer a scholar, researcher, scientist, policy maker, politician, professional journalist, or citizen blogger? ◊ Is the writer affiliated with conservative or liberal, religious or lay publications? ◊ Is the writer advocating a stance or adopting a more inquiry-based mode? ◊ What points of view and pieces of evidence are “not seen” by this writer?

What to Focus On On Rhetorical context: Writer’s identity and angle of vision

Questions to Ask ◊ Who is the writer and what is his or her profession, background, and expertise? ◊ How does the writer’s personal history, education, gender, ethnicity, age, class, sexual orientation, and political leaning influence the angle of vision? ◊ What is emphasized and what is omitted in this text? ◊ How much does the writer’s angle of vision dominate the text?

Applying These Questions ◊ Is the writer a scholar, researcher, scientist, policy maker, politician, professional journalist, or citizen blogger? ◊ Is the writer affiliated with conservative or liberal, religious or lay publications? ◊ Is the writer advocating a stance or adopting a more inquiry-based mode? ◊ What points of view and pieces of evidence are “not seen” by this writer?

Need help with the Commons?

Email us at [email protected] so we can respond to your questions and requests. Please email from your CUNY email address if possible. Or visit our help site for more information:

- Terms of Service

- Accessibility

- Creative Commons (CC) license unless otherwise noted

Typical College-level Writing Genres: Summary, Analysis, Synthesis

Basic questions for rhetorical analysis, what is the rhetorical situation.

- What occasion gives rise to the need or opportunity for persuasion?

- What is the historical occasion that would give rise to the composition of this text?

Who is the author/speaker?

- How does he or she establish ethos (personal credibility)?

- Does he/she come across as knowledgeable? fair?

- Does the speaker’s reputation convey a certain authority?

What is his/her intention in speaking?

- To attack or defend?

- To exhort or dissuade from certain action?

- To praise or blame?

- To teach, to delight, or to persuade?

Who make up the audience?

- Who is the intended audience?

- What values does the audience hold that the author or speaker appeals to?

- Who have been or might be secondary audiences?

- If this is a work of fiction, what is the nature of the audience within the fiction?

What is the content of the message?

- Can you summarize the main idea?

- What are the principal lines of reasoning or kinds of arguments used?

- What topics of invention are employed?

- How does the author or speaker appeal to reason? to emotion?

What is the form in which it is conveyed?

- What is the structure of the communication; how is it arranged?

- What oral or literary genre is it following?

- What figures of speech (schemes and tropes) are used?

- What kind of style and tone is used and for what purpose?

How do form and content correspond?

- Does the form complement the content?

- What effect could the form have, and does this aid or hinder the author’s intention?

Does the message/speech/text succeed in fulfilling the author’s or speaker’s intentions?

- Does the author/speaker effectively fit his/her message to the circumstances, times, and audience?

- Can you identify the responses of historical or contemporary audiences?

What does the nature of the communication reveal about the culture that produced it?

- What kinds of values or customs would the people have that would produce this?

- How do the allusions, historical references, or kinds of words used place this in a certain time and location?

- Basic Questions for Rhetorical Analysis. Authored by : Gideon O. Burton. Provided by : Brigham Young University. Located at : http://rhetoric.byu.edu . Project : Silva Rhetoricae. License : CC BY: Attribution

Rhetorical Analysis Definition and Examples

The analysis can be used on any communication, even a bumper sticker

- An Introduction to Punctuation

Sample Rhetorical Analyses

Examples and observations, analyzing effects, analyzing greeting card verse, analyzing starbucks, rhetorical analysis vs. literary criticism.

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

Rhetorical analysis is a form of criticism or close reading that employs the principles of rhetoric to examine the interactions between a text, an author, and an audience . It's also called rhetorical criticism or pragmatic criticism.

Rhetorical analysis may be applied to virtually any text or image—a speech , an essay , an advertisement, a poem, a photograph, a web page, even a bumper sticker. When applied to a literary work, rhetorical analysis regards the work not as an aesthetic object but as an artistically structured instrument for communication. As Edward P.J. Corbett has observed, rhetorical analysis "is more interested in a literary work for what it does than for what it is."

- A Rhetorical Analysis of Claude McKay's "Africa"

- A Rhetorical Analysis of E.B. White's "The Ring of Time"

- A Rhetorical Analysis of U2's "Sunday Bloody Sunday"

- "Our response to the character of the author—whether it is called ethos, or 'implied author,' or style , or even tone—is part of our experience of his work, an experience of the voice within the masks, personae , of the work...Rhetorical criticism intensifies our sense of the dynamic relationships between the author as a real person and the more or less fictive person implied by the work." (Thomas O. Sloan, "Restoration of Rhetoric to Literary Study." The Speech Teacher )

- "[R]hetorical criticism is a mode of analysis that focuses on the text itself. In that respect, it is like the practical criticism that the New Critics and the Chicago School indulge in. It is unlike these modes of criticism in that it does not remain inside the literary work but works outward from the text to considerations of the author and the audience...In talking about the ethical appeal in his 'Rhetoric,' Aristotle made the point that although a speaker may come before an audience with a certain antecedent reputation, his ethical appeal is exerted primarily by what he says in that particular speech before that particular audience. Likewise, in rhetorical criticism, we gain our impression of the author from what we can glean from the text itself—from looking at such things as his ideas and attitudes, his stance, his tone, his style. This reading back to the author is not the same sort of thing as the attempt to reconstruct the biography of a writer from his literary work. Rhetorical criticism seeks simply to ascertain the particular posture or image that the author is establishing in this particular work in order to produce a particular effect on a particular audience." (Edward P.J. Corbett, "Introduction" to " Rhetorical Analyses of Literary Works ")

"[A] complete rhetorical analysis requires the researcher to move beyond identifying and labeling in that creating an inventory of the parts of a text represents only the starting point of the analyst's work. From the earliest examples of rhetorical analysis to the present, this analytical work has involved the analyst in interpreting the meaning of these textual components—both in isolation and in combination—for the person (or people) experiencing the text. This highly interpretive aspect of rhetorical analysis requires the analyst to address the effects of the different identified textual elements on the perception of the person experiencing the text. So, for example, the analyst might say that the presence of feature x will condition the reception of the text in a particular way. Most texts, of course, include multiple features, so this analytical work involves addressing the cumulative effects of the selected combination of features in the text." (Mark Zachry, "Rhetorical Analysis" from " The Handbook of Business Discourse , " Francesca Bargiela-Chiappini, editor)

"Perhaps the most pervasive type of repeated-word sentence used in greeting card verse is the sentence in which a word or group of words is repeated anywhere within the sentence, as in the following example:

In quiet and thoughtful ways , in happy and fun ways , all ways , and always , I love you.

In this sentence, the word ways is repeated at the end of two successive phrases, picked up again at the beginning of the next phrase, and then repeated as part of the word always . Similarly, the root word all initially appears in the phrase 'all ways' and is then repeated in a slightly different form in the homophonic word always . The movement is from the particular ('quiet and thoughtful ways,' 'happy and fun ways'), to the general ('all ways'), to the hyperbolic ('always')." (Frank D'Angelo, "The Rhetoric of Sentimental Greeting Card Verse." Rhetoric Review )

"Starbucks not just as an institution or as a set of verbal discourses or even advertising but as a material and physical site is deeply rhetorical...Starbucks weaves us directly into the cultural conditions of which it is constitutive. The color of the logo, the performative practices of ordering, making, and drinking the coffee, the conversations around the tables, and the whole host of other materialities and performances of/in Starbucks are at once the rhetorical claims and the enactment of the rhetorical action urged. In short, Starbucks draws together the tripartite relationships among place, body, and subjectivity. As a material/rhetorical place, Starbucks addresses and is the very site of a comforting and discomforting negotiation of these relationships." (Greg Dickinson, "Joe's Rhetoric: Finding Authenticity at Starbucks." Rhetoric Society Quarterly )