Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Kirsten DeVries

At school, at work, and in everyday life, argument is one of main ways we exchange ideas with one another. Academics, business people, scientists, and other professionals all make arguments to determine what to do or think, or to solve a problem by enlisting others to do or believe something they otherwise would not. Not surprisingly, then, argument dominates writing, and training in argument writing is essential for all college students.

This chapter will explore how to define argument and how to talk about arguments.

1. What Is Argument?

2. What Are the Components and Vocabulary of Argument?

1. What Is Argument?

All people, including you, make arguments on a regular basis. When you make a claim and then support the claim with reasons, you are making an argument. Consider the following:

- If, as a teenager, you ever made a case for borrowing your parents’ car using reasonable support—a track record of responsibility in other areas of your life, a good rating from your driving instructor, and promises to follow rules of driving conduct laid out by your parents—you have made an argument.

- If, as an employee, you ever persuaded your boss to give you a raise using concrete evidence—records of sales increases in your sector, a work calendar with no missed days, and personal testimonials from satisfied customers—you have made an argument.

- If, as a gardener, you ever shared your crops at a farmer’s market, declaring that your produce is better than others using relevant support—because you used the most appropriate soil, water level, and growing time for each crop—you’ve made an argument.

- If, as a literature student, you ever wrote an essay on your interpretation of a poem—defending your ideas with examples from the text and logical explanations for how those examples demonstrate your interpretation—you have made an argument.

The two main models of argument desired in college courses as part of the training for academic or professional life are rhetorical argument and academic argument . If rhetoric is the study of the craft of writing and speaking, particularly writing or speaking designed to convince and persuade, the student studying rhetorical argument focuses on how to create an argument that convinces and persuades effectively. To that end, the student must understand how to think broadly about argument, the particular vocabulary of argument, and the logic of argument. The close sibling of rhetorical argument is academic argument, argument used to discuss and evaluate ideas, usually within a professional field of study, and to convince others of those ideas. In academic argument , interpretation and research play the central roles.

However, it would be incorrect to say that academic argument and rhetorical argument do not overlap. Indeed, they do, and often. A psychologist not only wishes to prove an important idea with research, but she will also wish to do so in the most effective way possible. A politician will want to make the most persuasive case for his side, but he should also be mindful of data that may support his points. Thus, throughout this chapter, when you see the term argument , it refers to a broad category including both rhetorical and academic argument .

Before moving to the specific parts and vocabulary of argument, it will be helpful to consider some further ideas about what argument is and what it is not.

Argument vs. Controversy or Fight

Consumers of written texts are often tempted to divide writing into two categories: argumentative and non-argumentative. According to this view, to be argumentative, writing must have the following qualities: It has to defend a position in a debate between two or more opposing sides, it must be on a controversial topic, and the goal of such writing must be to prove the correctness of one point of view over another.

A related definition of argument implies a confrontation, a clash of opinions and personalities, or just a plain verbal fight. It implies a winner and a loser, a right side and a wrong one. Because of this understanding of the word “argument,” many students think the only type of argument writing is the debate-like position paper, in which the author defends his or her point of view against other, usually opposing, points of view.

These two characteristics of argument—as controversial and as a fight—limit the definition because arguments come in different disguises, from hidden to subtle to commanding. It is useful to look at the term “argument” in a new way. What if we think of argument as an opportunity for conversation, for sharing with others our point of view on an issue, for showing others our perspective of the world? What if we think of argument as an opportunity to connect with the points of view of others rather than defeating those points of view?

One community that values argument as a type of communication and exchange is the community of scholars. They advance their arguments to share research and new ways of thinking about topics. Biologists, for example, do not gather data and write up analyses of the results because they wish to fight with other biologists, even if they disagree with the ideas of other biologists. They wish to share their discoveries and get feedback on their ideas. When historians put forth an argument, they do so often while building on the arguments of other historians who came before them. Literature scholars publish their interpretations of different works of literature to enhance understanding and share new views, not necessarily to have one interpretation replace all others. There may be debates within any field of study, but those debates can be healthy and constructive if they mean even more scholars come together to explore the ideas involved in those debates. Thus, be prepared for your college professors to have a much broader view of argument than a mere fight over a controversial topic or two.

Argument vs. Opinion

Argument is often confused with opinion. Indeed, arguments and opinions sound alike. Someone with an opinion asserts a claim that he thinks is true. Someone with an argument asserts a claim that she thinks is true. Although arguments and opinions do sound the same, there are two important differences:

- Arguments have rules; opinions do not . In other words, to form an argument, you must consider whether the argument is reasonable. Is it worth making? Is it valid? Is it sound? Do all of its parts fit together logically? Opinions, on the other hand, have no rules, and anyone asserting an opinion need not think it through for it to count as one; however, it will not count as an argument.

- Arguments have support; opinions do not . If you make a claim and then stop, as if the claim itself were enough to demonstrate its truthfulness, you have asserted an opinion only. An argument must be supported, and the support of an argument has its own rules. The support must also be reasonable, relevant, and sufficient.

Figure 3.1 “Opinion vs Argument”

Argument vs. Thesis

Another point of confusion is the difference between an argument and an essay’s thesis . For college essays, there is no essential difference between an argument and a thesis; most professors use these terms interchangeably. An argument is a claim that you must then support. The main claim of an essay is the point of the essay and provides the purpose for the essay. Thus, the main claim of an essay is also the thesis. For more on the thesis, see Chapter 4, “ The Writing Process.”

Consider this as well: Most formal essays center upon one main claim (the thesis) but then support that main claim with supporting evidence and arguments. The topic sentence of a body paragraph can be another type of argument, though a supporting one, and, hence, a narrower one. Try not to be confused when professors call both the thesis and topic sentences arguments. They are not wrong because arguments come in different forms; some claims are broad enough to be broken down into a number of supporting arguments. Many longer essays are structured by the smaller arguments that are a part of and support the main argument. Sometimes professors, when they say supporting points or supporting arguments, mean the reasons ( premises ) for the main claim ( conclusion ) you make in an essay. If a claim has a number of reasons, those reasons will form the support structure for the essay, and each reason will be the basis for the topic sentence of its body paragraph.

Argument vs. Fact

Arguments are also commonly mistaken for statements of fact. This comes about because often people privilege facts over opinions, even as they defend the right to have opinions. In other words, facts are “good,” and opinions are “bad,” or if not exactly bad, then fuzzy and thus easy to reject. However, remember the important distinction between an argument and an opinion stated above: While argument may sound like an opinion, the two are not the same. An opinion is an assertion, but it is left to stand alone with little to no reasoning or support. An argument is much stronger because it includes and demonstrates reasons and support for its claim.

As for mistaking a fact for an argument, keep this important distinction in mind: An argument must be arguable . In everyday life, arguable is often a synonym for doubtful. For an argument, though, arguable means that it is worth arguing, that it has a range of possible answers, angles, or perspectives: It is an answer, angle, or perspective with which a reasonable person might disagree. Facts, by virtue of being facts, are not arguable. Facts are statements that can be definitely proven using objective data. The statement that is a fact is absolutely valid. In other words, the statement can be pronounced as definitively true or definitively false. For example, 2 + 2 = 4. This expression identifies a verifiably true statement, or a fact, because it can be proved with objective data. When a fact is established, there is no other side, and there should be no disagreement.

The misunderstanding about facts (being inherently good) and argument (being inherently problematic because it is not a fact) leads to the mistaken belief that facts have no place in an argument. This could not be farther from the truth. First of all, most arguments are formed by analyzing facts. Second, facts provide one type of support for an argument. Thus, do not think of facts and arguments as enemies; rather, they work closely together.

Explicit vs. Implicit Arguments

Arguments can be both explicit and implicit. Explicit arguments contain prominent and definable thesis statements and multiple specific proofs to support them. This is common in academic writing from scholars of all fields. Implicit arguments , on the other hand, work by weaving together facts and narratives, logic and emotion, personal experiences and statistics. Unlike explicit arguments, implicit ones do not have a one-sentence thesis statement. Implicit arguments involve evidence of many different kinds to build and convey their point of view to their audience. Both types use rhetoric, logic, and support to create effective arguments.

Argument and Rhetoric

An argument in written form involves making choices, and knowing the principles of rhetoric allows a writer to make informed choices about various aspects of the writing process. Every act of writing takes place in a specific rhetorical situation. The most basic and important components of a rhetorical situation are

- Author of the text.

- Purpose of the text.

- Intended audience (i.e., those the author imagines will be reading the text).

- Form or type of text.

These components give readers a way to analyze a text on first encounter. These factors also help writers select their topics, arrange their material, and make other important decisions about the argument they will make and the support they will need. For more on rhetoric, see Chapter 2, “Rhetorical Analysis.”

Key Takeaways: What is an Argument?

With this brief introduction, you can see what rhetorical or academic argument is not :

- An argument need not be controversial or about a controversy.

- An argument is not a mere fight.

- An argument does not have a single winner or loser.

- An argument is not a mere opinion.

- An argument is not a statement of fact.

Furthermore, you can see what rhetorical argument is :

- An argument is a claim asserted as true.

- An argument is arguable.

- An argument must be reasonable.

- An argument must be supported.

- An argument in a formal essay is called a thesis. Supporting arguments can be called topic sentences.

- An argument can be explicit or implicit.

- An argument must be adapted to its rhetorical situation.

2. What Are the Components and Vocabulary of Argument?

Questions are at the core of arguments. What matters is not just that you believe that what you have to say is true, but that you give others viable reasons to believe it as well—and also show them that you have considered the issue from multiple angles. To do that, build your argument out of the answers to the five questions a rational reader will expect answers to. In academic and professional writing, we tend to build arguments from the answers to these main questions:

- What do you want me to do or think?

- Why should I do or think that?

- How do I know that what you say is true?

- Why should I accept the reasons that support your claim?

- What about this other idea, fact, or consideration?

- How should you present your argument?

When you ask people to do or think something they otherwise would not, they quite naturally want to know why they should do so. In fact, people tend to ask the same questions. As you make a reasonable argument, you anticipate and respond to readers’ questions with a particular part of argument:

1. The answer to What do you want me to do or think? is your conclusion : “I conclude that you should do or think X.”

2. The answer to Why should I do or think that? states your premise : “You should do or think X because . . .”

3. The answer to How do I know that what you say is true? presents your support : “You can believe my reasons because they are supported by these facts . . .”

4. The answer to Why should I accept that your reasons support your claim? states your general principle of reasoning, called a warrant : “My specific reason supports my specific claim because whenever this general condition is true, we can generally draw a conclusion like mine.”

5. The answer to What about this other idea, fact, or conclusion? acknowledges that your readers might see things differently and then responds to their counterarguments .

6. The answer to How should you present your argument? leads to the point of view , organization , and tone that you should use when making your arguments.

As you have noticed, the answers to these questions involve knowing the particular vocabulary about argument because these terms refer to specific parts of an argument. The remainder of this section will cover the terms referred to in the questions listed above as well as others that will help you better understand the building blocks of argument.

What Is a Conclusion, and What Is a Premise?

The root notion of an argument is that it convinces us that something is true. What we are being convinced of is the conclusion . An example would be this claim:

Littering is harmful.

A reason for this conclusion is called the premise . Typically, a conclusion will be supported by two or more premises . Both premises and conclusions are statements . Some premises for our littering conclusion might be these:

Littering is dangerous to animals.

Littering is dangerous to humans.

Thus, to be clear, understand that an argument asserts that the writer’s claim is true in two main parts: the premises of the argument exist to show that the conclusion is true.

Be aware of the other words to indicate a conclusion– claim , assertion , point –and other ways to talk about the premise– reason , factor , the why . Also, do not confuse this use of the word conclusion with a conclusion paragraph for an essay.

What Is a Statement?

A statement is a type of sentence that can be true or false and corresponds to the grammatical category of a declarative sentence . For example, the sentence,

The Nile is a river in northeastern Africa,

is a statement because it makes sense to inquire whether it is true or false. (In this case, it happens to be true.) However, a sentence is still a statement, even if it is false. For example, the sentence,

The Yangtze is a river in Japan,

is still a statement; it is just a false statement (the Yangtze River is in China). In contrast, none of the following sentences are statements:

Please help yourself to more casserole.

Don’t tell your mother about the surprise.

Do you like Vietnamese pho?

None of these sentences are statements because it does not make sense to ask whether those sentences are true or false; rather, they are a request, a command, and a question, respectively. Make sure to remember the difference between sentences that are declarative statements and sentences that are not because arguments depend on declarative statements .

A question cannot be an argument, yet students will often pose a question at the end of an introduction to an essay, thinking they have declared their thesis. They have not. If, however, they answer that question ( conclusion ) and give some reasons for that answer ( premises ), they then have the components necessary for both an argument and a declarative statement of that argument ( thesis ).

To reiterate: All arguments are composed of premises and conclusions, both of which are types of statements. The premises of the argument provide reasons for thinking that the conclusion is true. Arguments typically involve more than one premise.

What Is Standard Argument Form?

A standard way of capturing the structure of an argument, or diagramming it, is by numbering the premises and conclusion. For example, the following represents another way to arrange the littering argument:

- Littering is harmful

- Litter is dangerous to animals

- Litter is dangerous to humans

This numbered list represents an argument that has been put into standard argument form . A more precise definition of an argument now emerges, employing the vocabulary that is specific to academic and rhetorical arguments. An argument is a set of statements , some of which (the premises : statements 2 and 3 above) attempt to provide a reason for thinking that some other statement (the conclusion : statement 1) is true.

Diagramming an argument can be helpful when trying to figure out your essay’s thesis. Because a thesis is an argument, putting the parts of an argument into standard form can help sort ideas. You can transform the numbered ideas into a cohesive sentence or two for your thesis once you are more certain what your argument parts are.

Figure 3.2 “Argument Diagram”

Recognizing arguments is essential to analysis and critical thinking; if you cannot distinguish between the details (the support) of a piece of writing and what those details are there to support (the argument), you will likely misunderstand what you are reading. Additionally, studying how others make arguments can help you learn how to effectively create your own.

What Are Argument Indicators?

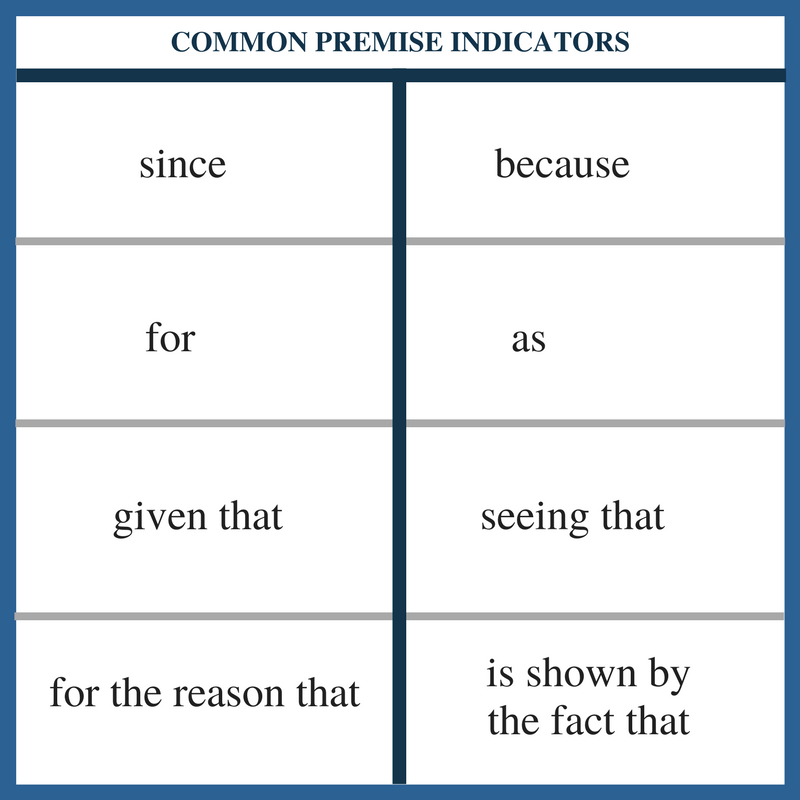

While mapping an argument in standard argument form can be a good way to figure out and formulate a thesis, identifying arguments by other writers is also important. The best way to identify an argument is to ask whether a claim exists (in statement form) that a writer justifies by reasons (also in statement form). Other identifying markers of arguments are key words or phrases that are premise indicators or conclusion indicators. For example, recall the littering argument, reworded here into a single sentence (much like a thesis statement):

Littering is harmful because it is dangerous to both animals and humans.

The word “because” here is a premise indicator . That is, “because” indicates that what follows is a reason for thinking that littering is bad. Here is another example:

The student plagiarized since I found the exact same sentences on a website, and the website was published more than a year before the student wrote the paper.

In this example, the word “since” is a premise indicator because what follows is a statement that is clearly intended to be a reason for thinking that the student plagiarized (i.e., a premise). Notice that in these two cases, the premise indicators “because” and “since” are interchangeable: “because” could be used in place of “since” or “since” in the place of “because,” and the meaning of the sentences would have been the same.

Figure 3.3 “Common Premise Indicators”

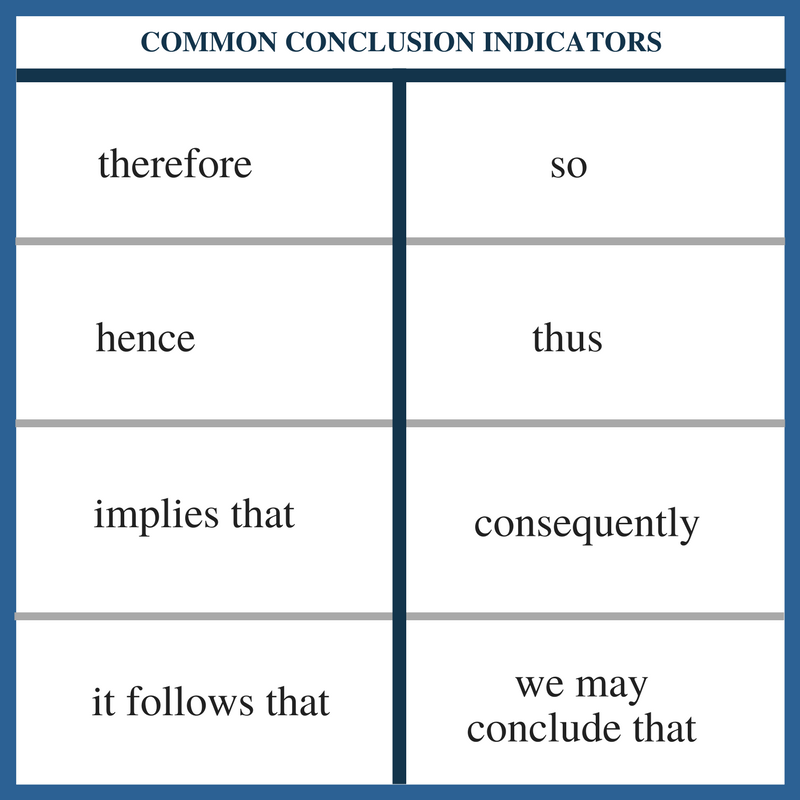

In addition to premise indicators, there are also conclusion indicators . Conclusion indicators mark that what follows is the conclusion of an argument. For example,

Bob-the-arsonist has been dead for a year, so Bob-the-arsonist didn’t set the fire at the East Lansing Starbucks last week.

In this example, the word “so” is a conclusion indicator because what follows it is a statement that someone is trying to establish as true (i.e., a conclusion). Here is another example of a conclusion indicator:

A poll administered by Gallup (a respected polling company) showed candidate X to be substantially behind candidate Y with only a week left before the vote; therefore , candidate Y will probably not win the election.

In this example, the word “therefore” is a conclusion indicator because what follows it is a statement that someone is trying to establish as true (i.e., a conclusion). As before, in both of these cases, the conclusion indicators “so” and “therefore” are interchangeable: “So” could be used in place of “therefore” or “therefore” in the place of “so,” and the meaning of the sentences would have been the same.

Figure 3.4 “Common Conclusion Indicators”

Which of the following are arguments? If it is an argument, identify the conclusion (claim) of the argument. If it is not an argument, explain why not. Remember to look for the qualifying features of an argument: (1) It is a statement or series of statements, (2) it states a claim (a conclusion), and (3) it has at least one premise (reason for the claim).

- The woman with the hat is not a witch since witches have long noses, and she doesn’t have a long nose.

- I have been wrangling cattle since before you were old enough to tie your own shoes.

- Albert is angry with me, so he probably won’t be willing to help me wash the dishes.

- First, I washed the dishes, and then I dried them.

- If the road weren’t icy, the car wouldn’t have slid off the turn.

- Marvin isn’t a fireman and isn’t a fisherman, either.

- Are you seeing the rhinoceros over there? It’s huge!

- Obesity has become a problem in the US because obesity rates have risen over the past four decades.

- Bob showed me a graph with rising obesity rates, and I was very surprised to see how much they had risen.

- Marvin isn’t a fireman because Marvin is a Greyhound, which is a type of dog, and dogs can’t be firemen.

- What Susie told you is not the actual reason she missed her flight to Denver.

- Carol likely forgot to lock her door this morning because she was distracted by a clown riding a unicycle while singing Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Simple Man.”

- No one who has ever gotten frostbite while climbing K2 has survived to tell about it; therefore, no one ever will.

What Constitutes Support?

To ensure that your argument is sound—that the premises for your conclusion are true—you must establish support . The burden of proof, to borrow language from law, is on the one making an argument, not on the recipient of an argument. If you wish to assert a claim, you must then also support it, and this support must be relevant, logical, and sufficient.

It is important to use the right kind of evidence, to use it effectively, and to have an appropriate amount of it.

- If, for example, your philosophy professor did not like that you used a survey of public opinion as your primary evidence in an ethics paper, you most likely used material that was not relevant to your topic. Rather, you should find out what philosophers count as good evidence. Different fields of study involve types of evidence based on relevance to those fields.

- If your professor has put question marks by your thesis or has written, “It does not follow,” you likely have problems with logic . Make sure it is clear how the parts of your argument logically fit together.

- If your instructor has told you that you need more analysis, suggested that you are “just listing” points or giving a “laundry list,” you likely have not included enough explanation for how a point connects to and supports your argument, which is another problem with logic , this time related to the warrants of your argument. You need to fully incorporate evidence into your argument. (See more on warrants immediately below.)

- If you see comments like “for example?,” “proof?,” “go deeper,” or “expand,” you may need more evidence. In other words, the evidence you have is not yet sufficient . One or two pieces of evidence will not be enough to prove your argument. Similarly, multiple pieces of evidence that aren’t developed thoroughly would also be flawed, also insufficient. Would a lawyer go to trial with only one piece of evidence? No, the lawyer would want to have as much evidence as possible from a variety of sources to make a viable case. Similarly, a lawyer would fully develop evidence for a claim using explanation, facts, statistics, stories, experiences, research, details, and the like.

You will find more information about the different types of evidence, how to find them, and what makes them credible in Chapter 6, “Research.” Logic will be covered later on in this chapter.

What Is the Warrant?

Above all, connect the evidence to the argument. This connection is the warrant . Evidence is not self-evident. In other words, after introducing evidence into your writing, you must demonstrate why and how this evidence supports your argument. You must explain the significance of the evidence and its function in your paper. What turns a fact or piece of information into evidence is the connection it has with a larger claim or argument: Evidence is always evidence for or against something, and you have to make that link clear.

Student writers sometimes assume that readers already know the information being written about; students may be wary of elaborating too much because they think their points are obvious. But remember, readers are not mind readers: Although they may be familiar with many of the ideas discussed, they don’t know what writers want to do with those ideas unless they indicate that through explanations, organization, and transitions. Thus, when you write, be sure to explain the connections you made in your mind when you chose your evidence, decided where to place it in your paper, and drew conclusions based on it.

What Is a Counterargument?

Remember that arguments are multi-sided. As you brainstorm and prepare to present your idea and your support for it, consider other sides of the issue. These other sides are counterarguments . Make a list of counterarguments as you work through the writing process, and use them to build your case – to widen your idea to include a valid counterargument, to explain how a counterargument might be defeated, to illustrate how a counterargument may not withstand the scrutiny your research has uncovered, and/or to show that you are aware of and have taken into account other possibilities.

For example, you might choose the issue of declawing cats and set up your search with the question should I have my indoor cat declawed? Your research, interviews, surveys, personal experiences might yield several angles on this question: Yes, it will save your furniture and your arms and ankles. No, it causes psychological issues for the cat. No, if the cat should get outside, he will be without defense. As a writer, be prepared to address alternate arguments and to include them to the extent that it will illustrate your reasoning.

Almost anything claimed in a paper can be refuted or challenged. Opposing points of view and arguments exist in every debate. It is smart to anticipate possible objections to your arguments – and to do so will make your arguments stronger. Another term for a counterargument is antithesis (i.e., the opposition to a thesis). To find possible counterarguments (and keep in mind there can be many counterpoints to one claim), ask the following questions:

- Could someone draw a different conclusion from the facts or examples you present?

- Could a reader question any of your assumptions or claims?

- Could a reader offer a different explanation of an issue?

- Is there any evidence out there that could weaken your position?

If the answer to any of these questions is yes, the next set of questions can help you respond to these potential objections:

Is it possible to concede the point of the opposition, but then challenge that point’s importance/usefulness?

- Can you offer an explanation of why a reader should question a piece of evidence or consider a different point of view?

- Can you explain how your position responds to any contradicting evidence?

- Can you put forward a different interpretation of evidence?

It may not seem likely at first, but clearly recognizing and addressing different sides of the argument, the ones that are not your own, can make your argument and paper stronger. By addressing the antithesis of your argument essay, you are showing your readers that you have carefully considered the issue and accept that there are often other ways to view the same thing.

You can use signal phrases in your paper to alert readers that you are about to present an objection. Consider using one of these phrases–or ones like them–at the beginning of a paragraph:

- Researchers have challenged these claims with…

- Critics argue that this view…

- Some readers may point to…

What Are More Complex Argument Structures?

So far you have seen that an argument consists of a conclusion and a premise (typically more than one). However, often arguments and explanations have a more complex structure than just a few premises that directly support the conclusion. For example, consider the following argument:

No one living in Pompeii could have survived the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius. The reason is simple: The lava was flowing too fast, and there was nowhere to go to escape it in time. Therefore, this account of the eruption, which claims to have been written by an eyewitness living in Pompeii, was not actually written by an eyewitness.

The main conclusion of this argument—the statement that depends on other statements as evidence but doesn’t itself provide any evidence for other statements—is

A. This account of the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius was not actually written by an eyewitness.

However, the argument’s structure is more complex than simply having a couple of premises that provide evidence directly for the conclusion. Rather, some statements provide evidence directly for the main conclusion, but some premise statements support other premise statements which then support the conclusion.

To determine the structure of an argument, you must determine which statements support which, using premise and conclusion indicators to help. For example, the passage above contains the phrase, “the reason is…” which is a premise indicator, and it also contains the conclusion indicator, “therefore.” That conclusion indicator helps identify the main conclusion, but the more important element to see is that statement A does not itself provide evidence or support for any of the other statements in the argument, which is the clearest reason statement A is the main conclusion of the argument. The next questions to answer are these: Which statement most directly supports A? What most directly supports A is

B. No one living in Pompeii could have survived the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius.

However, there is also a reason offered in support of B. That reason is the following:

C. The lava from Mt. Vesuvius was flowing too fast, and there was nowhere for someone living in Pompeii to go to escape it in time.

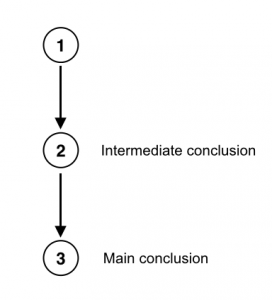

So the main conclusion (A) is directly supported by B, and B is supported by C. Since B acts as a premise for the main conclusion but is also itself the conclusion of further premises, B is classified as an intermediate conclusion . What you should recognize here is that one and the same statement can act as both a premise and a conclusion . Statement B is a premise that supports the main conclusion (A), but it is also itself a conclusion that follows from C. Here is how to put this complex argument into standard form (using numbers this time, as is typical for diagramming arguments):

- The lava from Mt. Vesuvius was flowing too fast, and there was nowhere for someone living in Pompeii to go to escape it in time.

- Therefore, no one living in Pompeii could have survived the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius. (from 1)

- Therefore, this account of the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius was not actually written by an eyewitness. (from 2)

Notice that at the end of statement 2 is a written indicator in parentheses (from 1), and, likewise, at the end of statement 3 is another indicator (from 2). From 1 is a shorthand way of saying, “this statement follows logically from statement 1.” Use this convention as a way to keep track of an argument’s structure. It may also help to think about the structure of an argument spatially, as the figure below shows:

The main argument here (from 2 to 3) contains a subargument , in this case, the argument from 1 (a premise) to 2 (the intermediate conclusion). A subargument, as the term suggests, is a part of an argument that provides indirect support for the main argument. The main argument is simply the argument whose conclusion is the main conclusion.

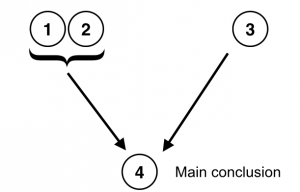

Another type of structure that arguments can have is when two or more premises provide direct but independent support for the conclusion. Here is an example of an argument with that structure:

Wanda rode her bike to work today because when she arrived at work she had her right pant leg rolled up, which cyclists do to keep their pants legs from getting caught in the chain. Moreover, our co-worker, Bob, who works in accounting, saw her riding towards work at 7:45 a.m.

The conclusion of this argument is “Wanda rode her bike to work today”; two premises provide independent support for it: the fact that Wanda had her pant leg cuffed and the fact that Bob saw her riding her bike. Here is the argument in standard form:

- Wanda arrived at work with her right pant leg rolled up.

- Cyclists often roll up their right pant leg.

- Bob saw Wanda riding her bike towards work at 7:45.

- Therefore, Wanda rode her bike to work today. (from 1-2, 3 independently)

Again, notice that next to statement 4 of the argument is an indicator of how each part of the argument relates to the main conclusion. In this case, to avoid any ambiguity, you can see that the support for the conclusion comes independently from statements 1 and 2, on the one hand, and from statement 3, on the other hand. It is important to point out that an argument or subargumen t can be supported by one or more premises, the case in this argument because the main conclusion (4) is supported jointly by 1 and 2, and singly by 3. As before, we can represent the structure of this argument spatially, as the figure below shows:

There are endless argument structures that can be generated from a few simple patterns. At this point, it is important to understand that arguments can have different structures and that some arguments will be more complex than others. Determining the structure of complex arguments is a skill that takes some time to master, rather like simplifying equations in math. Even so, it may help to remember that any argument structure ultimately traces back to some combination of premises, intermediate arguments, and a main conclusion.

Write the following arguments in standard form. If any arguments are complex, show how each complex argument is structured using a diagram like those shown just above.

1. There is nothing wrong with prostitution because there is nothing wrong with consensual sexual and economic interactions between adults. Moreover, there is no difference between a man who goes on a blind date with a woman, buys her dinner and then has sex with her and a man who simply pays a woman for sex, which is another reason there is nothing wrong with prostitution.

2. Prostitution is wrong because it involves women who have typically been sexually abused as children. Proof that these women have been abused comes from multiple surveys done with female prostitutes that show a high percentage of self-reported sexual abuse as children.

3. Someone was in this cabin recently because warm water was in the tea kettle and wood was still smoldering in the fireplace. However, the person couldn’t have been Tim because Tim has been with me the whole time. Therefore, someone else must be in these woods.

4. Someone can be blind and yet run in the Olympic Games since Marla Runyan did it at the 2000 Sydney Olympics.

5. The train was late because it had to take a longer, alternate route seeing as the bridge was out.

6. Israel is not safe if Iran gets nuclear missiles because Iran has threatened multiple times to destroy Israel, and if Iran had nuclear missiles, it would be able to carry out this threat. Furthermore, since Iran has been developing enriched uranium, it has the key component needed for nuclear weapons; every other part of the process of building a nuclear weapon is simple compared to that. Therefore, Israel is not safe.

7. Since all professional hockey players are missing front teeth, and Martin is a professional hockey player, it follows that Martin is missing front teeth. Because almost all professional athletes who are missing their front teeth have false teeth, it follows that Martin probably has false teeth.

8. Anyone who eats the crab rangoon at China Food restaurant will probably have stomach troubles afterward. It has happened to me every time; thus, it will probably happen to other people as well. Since Bob ate the crab rangoon at China Food restaurant, he will probably have stomach troubles afterward.

9. Lucky and Caroline like to go for runs in the afternoon in Hyde Park. Because Lucky never runs alone, any time Albert is running, Caroline must also be running. Albert looks like he has just run (since he is panting hard), so it follows that Caroline must have run, too.

10. Just because Linda’s prints were on the gun that killed Terry and the gun was registered to Linda, it doesn’t mean that Linda killed Terry since Linda’s prints would certainly be on her own gun, and someone else could have stolen her gun and used it to kill Terry.

Key Takeaways: Components of Vocabulary and Argument

- Conclusion —a claim that is asserted as true. One part of an argument.

- Premise —a reason behind a conclusion. The other part of an argument. Most conclusions have more than one premise.

- Statement —a declarative sentence that can be evaluated as true or false. The parts of an argument, premises and the conclusion, should be statements.

- Standard Argument Form —a numbered breakdown of the parts of an argument (conclusion and all premises).

- Premise Indicators —terms that signal that a premise, or reason, is coming.

- Conclusion Indicator —terms that signal that a conclusion, or claim, is coming.

- Support —anything used as proof or reasoning for an argument. This includes evidence, experience, and logic.

- Warrant —the connection made between the support and the reasons of an argument.

- Counterargument —an opposing argument to the one you make. An argument can have multiple counterarguments.

- Complex Arguments –these are formed by more than individual premises that point to a conclusion. Complex arguments may have layers to them, including an intermediate argument that may act as both a conclusion (with its own premises) and a premise (for the main conclusion).

CC Licensed Content, Shared Previously

About Writing: A Guide, Robin Jeffrey, CC-BY.

A Concise Introduction to Logic, Craig DeLancey, CC-BY-NC-SA.

English 112: College Composition II , Lumen Learning, CC-BY-SA.

English Composition 1 , Lumen Learning, CC-BY-SA.

Frameworks for Academic Writing , Stephen Poulter, CC-BY-NC-SA.

Introduction to Logic and Critical Thinking, Matthew J. Van Cleave, CC-BY.

Methods of Discovery, Pavel Zemilanski, CC-BY-NC-SA.

Writing for Success , CC-BY-NC-SA.

Writing in College: From Competence to Excellence , Amy Guptill, CC-BY-NC-SA.

Image Credits

Figure 3.1 “Opinion vs Argument,” by Kalyca Schultz, Virginia Western Community College, derivative image from original by ijmaki, pixabay, CC-0.

Figure 3.2 “Argument Diagram,” Virginia Western Community College, derivative image using “ Thin Brace Down ,” by pathoschild, Wikimedia, CC-BY-SA 3.0.

Figure 3.3 “Common Premise Indicators,” by Kalyca Schultz, Virginia Western Community College, CC-0.

Figure 3.4 “Common Conclusion Indicators,” by Kalyca Schultz, Virginia Western Community College, CC-0.

Figure 3.5 Untitled, by Matthew Van Cleave, from Introduction to Logic and Critical Thinking , CC-BY.

Figure 3.6 Untitled, by Matthew Van Cleave, from Introduction to Logic and Critical Thinking , CC-BY.

Argument Copyright © 2021 by Kirsten DeVries is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Wanda M. Waller

Student Learning Outcomes

- Identify the elements of an argumentative essay

- Create the structure of an argumentative essay

- Develop an argumentative essay

What Is Argumentation?

Arguments are everywhere, and practically everything is or has been debated at some time. Your ability to develop a point of view on a topic and provide evidence is the process known as Argumentation. Argumentation asserts the reasonableness of a debatable position, belief, or conclusion. This process teaches us how to evaluate conflicting claims and judge evidence and methods of investigation while helping us to clarify our thoughts and articulate them accurately. Arguments also consider the ideas of others in a respectful and critical manner. In argumentative writing, you are typically asked to take a position on an issue or topic and explain and support your position. The purpose of the argument essay is to establish the writer’s opinion or position on a topic and persuade others to share or at least acknowledge the validity of your opinion.

Structure of the Argumentative Essay

An effective argumentative essay introduces a compelling, debatable topic to engage the reader. In an effort to persuade others to share your opinion, the writer should explain and consider all sides of an issue fairly and address counterarguments or opposing perspectives. The following five features make up the structure of an argumentative essay:

Introduction

The argumentative essay begins with an introduction that provides appropriate background to inform the reader about the topic. Your introduction may start with a quote, a personal story, a surprising statistic, or an interesting question. This strategy engages the reader’s attention while introducing the topic of the essay. The background information is a short description of your topic. In this section, you should include any information that your reader needs to understand your topic.

Thesis Statement

A thesis statement is one sentence in your introductory paragraph that concisely summarizes your main point(s) and claim(s) and presents your position on the topic. The thesis statement or main claim must be debatable. In other words, the thesis must be something that people could reasonably have differing opinions on.

Body Paragraphs and Supporting Details

Your argument must use an organizational structure that is logical and persuasive. There are three types of argumentative essays, each with differing organizational structures: Classical, Toulmin, and Rogerian.

Organization of the Classical Argument

The Classical Argument was developed by a Greek philosopher, Aristotle. It is the most common. The goal of this model is to convince the reader about a particular point of view. The Classical Argument relies on appeals to persuade an audience specifically: ethos (ethical appeal) is an appeal to the writer’s creditability, logos (logical appeal) is an appeal based on logic, and pathos (pathetic appeal) is an appeal based on emotions. The structure of the classical model is as follows:

- Introductory paragraph includes the thesis statement

- Background on the topic provides information to the reader about the topic

- Supporting evidence integrates appeals

- Counterargument and rebuttal address major opposition

- Conclusion restates the thesis statement

Organization of the Toulmin Argument

The Toulmin Argument was developed by Stephen Toulmin. The Toulmin method works well when there are no clear truths or solutions to a problem. It considers the complex nature of most situations. There are six basic components:

- Introduction—thesis statement or the main claim (statement of opinion)

- Grounds —the facts, data, or reasoning on which the claim is based

- Warrant —logic and reasoning that connect the ground to the claim

- Backing—additional support for the claim that addresses different questions related to the claim

- Qualifier —expressed limits to the claim stating the claim may not be true in all situations

- Rebuttal—counterargument against the claim

Organization of the Rogerian Argument

The Rogerian Argument was developed by Carl Rogers. Rogerian argument is a negotiating strategy in which common goals are identified and opposing views are described as objectively as possible in an effort to establish common ground and reach an agreement. Whereas the traditional argument focuses on winning , the Rogerian model seeks a mutually satisfactory solution. This argument considers different standpoints and works on collaboration and cooperation. Following is the structure of the Rogerian model:

- Introduction and Thesis Statement—presents the topic as a problem to solve together, rather than an issue

- Opposing Position—expressed acknowledgment of counterargument that is fair and accurate

- Statement of Claim—writer’s perspective

- Middle Ground —discussion of a compromised solution

- Conclusion—remarks stating the benefits of a compromised solution

The Following Words and Phrases: Writing an Argument

Using transition words or phrases at the beginning of new paragraphs or within paragraphs helps a reader to follow your writing. Transitions show the reader when you are moving on to a different idea or further developing the same idea. Transitions create a flow, or connection, among all sentences, and that leads to coherence in your writing. The following words and phrases will assist in linking ideas, moving your essay forward, and improving readability:

- Also, in the same way, just as, likewise, similarly

- But, however, in spite of, on the one hand, on the other hand, nevertheless, nonetheless, notwithstanding, in contrast, on the contrary, still yet

- First, second, third…, next, then, finally

- After, afterward, at last, before, currently, during, earlier, immediately, later, meanwhile, now, recently, simultaneously, subsequently, then

- For example, for instance, namely, specifically, to illustrate

- Even, indeed, in fact, of course, truly, without question, clearly

- Above, adjacent, below, beyond, here, in front, in back, nearby, there

- Accordingly, consequently, hence, so, therefore, thus

- Additionally, again, also, and, as well, besides, equally important, further, furthermore, in addition, moreover, then

- Finally, in a word, in brief, briefly, in conclusion, in the end, in the final analysis, on the whole, thus, to conclude, to summarize, in sum, to sum up, in summary

Professional Writing Example

The following essay, “Universal Health Care Coverage for the United States,” by Scott McLean is an argumentative essay. As you read the essay, determine the author’s major claim and major supporting examples that support his claim.

Universal Health Care Coverage for the United States

By Scott McLean

The United States is the only modernized Western nation that does not offer publicly funded health care to all its citizens; the costs of health care for the uninsured in the United States are prohibitive, and the practices of insurance companies are often more interested in profit margins than providing health care. These conditions are incompatible with US ideals and standards, and it is time for the US government to provide universal health care coverage for all its citizens. Like education, health care should be considered a fundamental right of all US citizens, not simply a privilege for the upper and middle classes.

One of the most common arguments against providing universal health care coverage (UHC) is that it will cost too much money. In other words, UHC would raise taxes too much. While providing health care for all US citizens would cost a lot of money for every tax-paying citizen, citizens need to examine exactly how much money it would cost, and more important, how much money is “too much” when it comes to opening up health care for all. Those who have health insurance already pay too much money, and those without coverage are charged unfathomable amounts. The cost of publicly funded health care versus the cost of current insurance premiums is unclear. In fact, some Americans, especially those in lower income brackets, could stand to pay less than their current premiums.

However, even if UHC would cost Americans a bit more money each year, we ought to reflect on what type of country we would like to live in, and what types of morals we represent if we are more willing to deny health care to others on the basis of saving a couple hundred dollars per year. In a system that privileges capitalism and rugged individualism, little room remains for compassion and love. It is time that Americans realize the amorality of US hospitals forced to turn away the sick and poor. UHC is a health care system that aligns more closely with the core values that so many Americans espouse and respect, and it is time to realize its potential.

Another common argument against UHC in the United States is that other comparable national health care systems, like that of England, France, or Canada, are bankrupt or rife with problems. UHC opponents claim that sick patients in these countries often wait in long lines or long wait lists for basic health care. Opponents also commonly accuse these systems of being unable to pay for themselves, racking up huge deficits year after year. A fair amount of truth lies in these claims, but Americans must remember to put those problems in context with the problems of the current US system as well. It is true that people often wait to see a doctor in countries with UHC, but we in the United States wait as well, and we often schedule appointments weeks in advance, only to have onerous waits in the doctor’s “waiting rooms.”

Critical and urgent care abroad is always treated urgently, much the same as it is treated in the United States. The main difference there, however, is cost. Even health insurance policy holders are not safe from the costs of health care in the United States. Each day an American acquires a form of cancer, and the only effective treatment might be considered “experimental” by an insurance company and thus is not covered. Without medical coverage, the patient must pay for the treatment out of pocket. But these costs may be so prohibitive that the patient will either opt for a less effective, but covered, treatment; opt for no treatment at all; or attempt to pay the costs of treatment and experience unimaginable financial consequences. Medical bills in these cases can easily rise into the hundreds of thousands of dollars, which is enough to force even wealthy families out of their homes and into perpetual debt. Even though each American could someday face this unfortunate situation, many still choose to take the financial risk. Instead of gambling with health and financial welfare, US citizens should press their representatives to set up UHC, where their coverage will be guaranteed and affordable.

Despite the opponents’ claims against UHC, a universal system will save lives and encourage the health of all Americans. Why has public education been so easily accepted, but not public health care? It is time for Americans to start thinking socially about health in the same ways they think about education and police services: as rights of US citizens.

Discussion Questions

- What is the author’s main claim in this essay?

- Does the author fairly and accurately present counterarguments to this claim? Explain your answer using evidence from the essay.

- Does the author provide sufficient background information for his reader about this topic? Point out at least one example in the text where the author provides background on the topic. Is it enough?

- Does the author provide a course of action in his argument? Explain your response using specific details from the essay.

Student Writing Example

Salvaging our old-growth forests.

It’s been so long since I’ve been there I can’t clearly remember what it’s like. I can only look at the pictures in my family photo album. I found the pictures of me when I was a little girl standing in front of a towering tree with what seems like endless miles and miles of forest in the background. My mom is standing on one side of me holding my hand, and my older brother is standing on the other side of me, making a strange face. The faded pictures don’t do justice to the real-life magnificence of the forest in which they were taken—the Olympic National Forest—but they capture the awe my parents felt when they took their children to the ancient forest.

Today these forests are threatened by the timber companies that want state and federal governments to open protected old-growth forests to commercial logging. The timber industry’s lobbying attempts must be rejected because the logging of old-growth forests is unnecessary, because it will destroy a delicate and valuable ecosystem, and because these rare forests are a sacred trust.

Those who promote logging of old-growth forests offer several reasons, but when closely examined, none is substantial. First, forest industry spokesmen tell us the forest will regenerate after logging is finished. This argument is flawed. In reality, the logging industry clear-cuts forests on a 50-80 year cycle, so that the ecosystem being destroyed—one built up over more than 250 years—will never be replaced. At most, the replanted trees will reach only one-third the age of the original trees. Because the same ecosystem cannot rebuild if the trees do not develop full maturity, the plants and animals that depend on the complex ecosystem—with its incredibly tall canopies and trees of all sizes and ages—cannot survive. The forest industry brags about replaceable trees but doesn’t mention a thing about the irreplaceable ecosystems.

Another argument used by the timber industry, as forestry engineer D. Alan Rockwood has said in a personal correspondence, is that “an old-growth forest is basically a forest in decline….The biomass is decomposing at a higher rate than tree growth.” According to Rockwood, preserving old-growth forests is “wasting a resource” since the land should be used to grow trees rather than let the old ones slowly rot away, especially when harvesting the trees before they rot would provide valuable lumber. But the timber industry looks only at the trees, not at the incredibly diverse bio-system which the ancient trees create and nourish. The mixture of young and old-growth trees creates a unique habitat that logging would destroy.

Perhaps the main argument used by the logging industry is economic. Using the plight of loggers to their own advantage, the industry claims that logging old-growth forests will provide jobs. They make all of us feel sorry for the loggers by giving us an image of a hardworking man put out of work and unable to support his family. They make us imagine the sad eyes of the logger’s children. We think, “How’s he going to pay the electricity bill? How’s he going to pay the mortgage? Will his family become homeless?” We all see these images in our minds and want to give the logger his job so his family won’t suffer. But in reality giving him his job back is only a temporary solution to a long-term problem. Logging in the old-growth forest couldn’t possibly give the logger his job for long. For example, according to Peter Morrison of the Wilderness Society, all the old-growth forests in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest would be gone in three years if it were opened to logging (vi). What will the loggers do then? Loggers need to worry about finding new jobs now and not wait until there are no old-growth trees left.

Having looked at the views of those who favor logging of old-growth forests, let’s turn to the arguments for preserving all old growth. Three main reasons can be cited.

First, it is simply unnecessary to log these forests to supply the world’s lumber. According to environmentalist Mark Sagoff, we have plenty of new-growth forests from which timber can be taken (89-90). Recently, there have been major reforestation efforts all over the United States, and it is common practice now for loggers to replant every tree that is harvested. These new-growth forests, combined with extensive planting of tree farms, provide more than enough wood for the world’s needs. According to forestry expert Robert Sedjo (qtd. in Sagoff 90), tree farms alone can supply the world’s demand for industrial lumber. Although tree farms are ugly and possess little diversity in their ecology, expanding tree farms is far preferable to destroying old-growth forests.

Moreover, we can reduce the demand for lumber. Recycling, for example, can cut down on the use of trees for paper products. Another way to reduce the amount of trees used for paper is with a promising new innovation, kenaf, a fast-growing, 15-foot-tall, annual herb that is native to Africa. According to Jack Page in Plant Earth, Forest, kenaf has long been used to make rope, and it has been found to work just as well for paper pulp (158).

Another reason to protect old-growth forests is the value of their complex and very delicate ecosystem. The threat of logging to the northern spotted owl is well known. Although loggers say “people before owls,” ecologists consider the owls to be warnings, like canaries in mine shafts that signal the health of the whole ecosystem. Evidence provided by the World Resource Institute shows that continuing logging will endanger other species. Also, Dr. David Brubaker, an environmentalist biologist at Seattle University, has said in a personal interview that the long-term effects of logging will be severe. Loss of the spotted owl, for example, may affect the small rodent population, which at the moment is kept in check by the predator owl. Dr. Brubaker also explained that the old-growth forests also connect to salmon runs. When dead timber falls into the streams, it creates a habitat conducive to spawning. If the dead logs are removed, the habitat is destroyed. These are only two examples in a long list of animals that would be harmed by logging of old-growth forests.

Finally, it is wrong to log in old-growth forests because of their sacred beauty. When you walk in an old-growth forest, you are touched by a feeling that ordinary forests can’t evoke. As you look up to the sky, all you see is branch after branch in a canopy of towering trees. Each of these amazingly tall trees feels inhabited by a spirit; it has its own personality. “For spiritual bliss take a few moments and sit quietly in the Grove of the patriarchs near Mount Rainier or the redwood forests of Northern California,” said Richard Linder, environmental activist and member of the National Wildlife Federation. “Sit silently,” he said, “and look at the giant living organisms you’re surrounded by; you can feel the history of your own species.” Although Linder is obviously biased in favor of preserving the forests, the spiritual awe he feels for ancient trees is shared by millions of other people who recognize that we destroy something of the world’s spirit when we destroy ancient trees, or great whales, or native runs of salmon. According to Al Gore, “We have become so successful at controlling nature that we have lost our connection to it” (qtd. in Sagoff 96). We need to find that connection again, and one place we can find it is in the old-growth forests.

The old-growth forests are part of the web of life. If we cut this delicate strand of the web, we may end up destroying the whole. Once the old trees are gone, they are gone forever. Even if foresters replanted every tree and waited 250 years for the trees to grow to ancient size, the genetic pool would be lost. We’d have a 250-year-old tree farm, not an old-growth forest. If we want to maintain a healthy earth, we must respect the beauty and sacredness of the old-growth forests.

Works Cited

Brubaker, David. Personal interview. 25 Sept. 1998.

Linder, Richard. Personal interview. 12 Sept. 1998.

Morrison, Peter. Old Growth in the Pacific Northwest: A Status Report. Alexandria: Global Printing, 1988.

Page, Jack. Planet Earth, Forest. Alexandria: Time-Life, 1983.

Rockwood, D. Alan. Email to the author. 24 Sept. 1998.

Sagoff, Mark. “Do We Consume Too Much?” Atlantic Monthly June 1997: 80-96.

World Resource Institute. “Old Growth Forests in the United States Pacific Northwest.” 13 Sept. 1998 http://www.wri.org/biodiv.

- Does the author fairly and accurately present counterarguments to this claim? Explain your answer and describe an example of counterargument in the essay.

What societal or personal experiences have you observed and considered to be argumentative?

What organizational structure would be best for the topic you consider: Classical, Toulmin, or Rogerian?

- Counterargument

- Classical method

- Toulmin method

- Rogerian method

- Middle Ground

- Argumentation

In argumentative writing, you are typically asked to take a position on an issue or topic and explain and support your position with research from reliable and credible sources. Argumentation can be used to convince readers to accept or acknowledge the validity of your position or to question or refute a position you consider to be untrue or misguided.

- The purpose of argument in writing is to convince or move readers toward a certain point of view, or opinion.

- An argument is a reasoned opinion supported and explained by evidence. To argue, in writing, is to advance knowledge and ideas in a positive way.

- A thesis that expresses the opinion of the writer in more specific terms is better than one that is vague.

- It is essential that you not only address counterarguments but also do so respectfully.

- It is also helpful to establish the limits of your argument and what you are trying to accomplish through a concession statement.

- To persuade a skeptical audience, you will need to use a wide range of evidence. Scientific studies, opinions from experts, historical precedent, statistics, personal anecdotes, and current events are all types of evidence that you might use in explaining your point.

- Make sure that your word choice and writing style are appropriate for both your subject and your audience.

- You should let your reader know your bias, but do not let that bias blind you to the primary components of good argumentation: sound, thoughtful evidence and respectfully and reasonably addressing opposing ideas.

- You should be mindful of the use of I in your writing because it can make your argument sound more biased than it needs to.

- Facts are statements that can be proven using objective data.

- Opinions are personal views, or judgments, that cannot be proven.

- In writing, you want to strike a balance between credible facts and authoritative opinions.

- Quantitative visuals present data graphically. The purpose of using quantitative visuals is to make logical appeals to the audience.

- Qualitative visuals present images that appeal to the audience’s emotions

Reflective Response

Reflect on your writing process for the argumentative essay. What was the most challenging? What was the easiest? Did your position on the topic change as a result of reviewing and evaluating new knowledge or ideas about the topic?

The Classical Argument was developed by a Greek philosopher, Aristotle. The goal of this model is to convince the reader about a particular point of view using appeals to persuade an audience.

In writing, an appeal is a strategy that a writer uses to support an argument.

Ethos is an appeal based on the writer’s creditability

Logical appeal is the strategic use of logic, claims, and evidence to convince an audience of a certain point. The writer uses logical connections between ideas, facts, and statistics.

Pathos, or the appeal to emotion, is an appeal to the reader’s emotion. The writer evokes the reader’s emotion with vivid language and powerful language to establish the writer’s belief.

A counterargument is an expressed acknowledgement of opposing views that are fair and accurate coupled with a response to the shortcoming in reasoning in the opposing views.

The Toulmin Argument was developed by Stephen Toulmin. The method works best when there are no clear truths or solutions to a problem

The facts, data, or reasoning on which a claim is based

A Warrant is a component of the Toulmin argument that connects the ground to the claim.

The Qualifier is a component of the Toulmin argument that expresses limits to the claim.

The Rogerian Argument was developed by Carl Rogers. Rogerian argument is a negotiating strategy in which common goals are identified and opposing views are described as objectively as possible in an effort to establish common ground and reach an agreement.

Middle Ground is part of the structure of the Rogerian argument. It is a discussion of compromised solutions

Argument Copyright © 2022 by Wanda M. Waller is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- I'M AN INSTRUCTOR

- I'M A STUDENT

Find what you need to succeed.

- Our Mission

- Our Leadership

- Learning Science

- Macmillan Learning AI

- Sustainability

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- Accessibility

- Astronomy Biochemistry Biology Chemistry College Success Communication Economics Electrical Engineering English Environmental Science Geography Geology History Mathematics Music & Theater Nutrition and Health Philosophy & Religion Physics Psychology Sociology Statistics Value

- Digital Offerings

- Inclusive Access

- Lab Solutions

- LMS Integration

- Curriculum Solutions

- Training and Demos

- First Day of Class

- Administrators

- Affordable Solutions

- Badging & Certification

- iClicker and Your Content

- Student Store

- News & Media

- Contact Us & FAQs

- Find Your Rep

- Booksellers

- Macmillan International Support

- International Translation Rights

- Request Permissions

- Report Piracy

Everything's an Argument

Psychology in Everyday Life

Ninth edition | ©2022 andrea a. lunsford; john j. ruszkiewicz, learn more about achieve for everything’s an argument with readings →.

ISBN:9781319413286

Take notes, add highlights, and download our mobile-friendly e-books.

ISBN:9781319244484

Read and study old-school with our bound texts.

ISBN:9781319521097

This package includes Achieve and Paperback.

EVERYTHING you need to teach argument

Streamlined and current, Everything’s an Argument helps students understand and analyze the arguments around them as well as create their own. Lucid explanations with contemporary examples cover classical rhetoric of oration through the multimodal rhetoric of today’s new media, with professional and student models of every type. More important than ever given today’s contentious political climate, a solid foundation in rhetorical listening and critical reading skills teaches students to communicate effectively and ethically. Thoroughly updated with fresh new models, this edition of Everything’s an Argument captures the issues and images that matter to students today. New coverage of lateral reading teaches students to evaluate arguments effectively and quickly, especially online. Interactive tutorials offer students more support for critical reading in an engaging digital format within Achieve with Everything’s an Argument , now available with writing assignments, reading quizzes, analysis and reflection activities, and more. Also available in a version with a five-chapter thematic reader.

New to This Edition

“ Everythings an Argument is an excellent textbook choice for English composition instructors. It not only defines argument in a detailed manner, it also provides readings concerning real-life examples that will keep students and me talking about the text inside and outside the classroom.” – Grace Nambela, Riverside Community College “ Everything’s an Argument is one of the best argument textbooks that I have worked with. My students connected to the readings, and the examples and Respond questions were great!” – Natalie Pleimann, North Lake College

Ninth Edition | ©2022

Andrea A. Lunsford; John J. Ruszkiewicz

Digital Options

Achieve is a comprehensive set of interconnected teaching and assessment tools that incorporate the most effective elements from Macmillan Learning's market leading solutions in a single, easy-to-use platform.

Schedule Achieve Demo

Read online (or offline) with all the highlighting and notetaking tools you need to be successful in this course.

Learn About E-book

Everything's an Argument

Ninth Edition | 2022

Table of Contents

Andrea A. Lunsford

Andrea Lunsford , Louise Hewlett Nixon Professor of English emerita and former Director of the Program in Writing and Rhetoric at Stanford University, joined the Stanford faculty in 2000. Prior to this appointment, she was Distinguished Professor of English at The Ohio State University (1986-2000) and, before that, Associate Professor and Director of Writing at the University of British Columbia (1977-86) and Associate Professor of English at Hillsborough Community College. A frequent member of the faculty of the Bread Loaf School of English, Andrea earned her B.A. and M.A. degrees from the University of Florida and completed her Ph.D. in English at The Ohio State University (1977). She holds honorary degrees from Middlebury College and The University of Ôrebro. Andreas scholarly interests include the contributions of women and people of color to rhetorical history, theory, and practice; collaboration and collaborative writing, comics/graphic narratives; translanguaging and style, and technologies of writing. She has written or coauthored many books, including Essays on Classical Rhetoric and Modern Discourse; Singular Texts/Plural Authors: Perspectives on Collaborative Writing; and Reclaiming Rhetorica: Women in the History of Rhetoric , as well as numerous chapters and articles. For Bedford/St. Martin’s, she is the author of The St. Martins Handbook, The Everyday Writer , and EasyWriter; the co-author (with John Ruszkiewicz) of Everything’s an Argument and (with John Ruszkiewicz and Keith Walters) of Everything’s an Argument with Readings; and the co-author (with Lisa Ede) of Writing Together: Collaboration in Theory and Practice . She is also a regular contributor to the Bits teaching blog on Bedford/St. Martin’s English Community site. Andrea has given presentations and workshops on the changing nature and scope of writing and critical language awareness at scores of North American universities, served as Chair of the Conference on College Composition and Communication, as Chair of the Modern Language Association Division on Writing, and as a member of the MLA Executive Council. In her spare time, she serves on the Board of La Casa Roja’s Next Generation Leadership Network, as Chair of the Kronos Quartet Performing Arts Association--and works diligently if not particularly well in her communal organic garden.

John J. Ruszkiewicz

John J. Ruszkiewicz is a professor emeritus at the University of Texas at Austin where he taught literature, rhetoric, and writing for forty years. A winner of the President’s Associates Teaching Excellence Award, he was instrumental in creating the Department of Rhetoric and Writing in 1993 and directed the unit from 2001-05. He has also served as president of the Conference of College Teachers of English (CCTE) of Texas, which gave him its Frances Hernández Teacher—Scholar Award in 2012. For Bedford/St. Martins, he is coauthor, with Andrea Lunsford, of Everything’s an Argument and the author of How to Write Anything. In retirement, he writes the mystery novels under the pen name J.J. Rusz; the most recent, The Lost Mine Trail, published in 2020 on Amazon.

Ninth Edition | 2022

Instructor Resources

Need instructor resources for your course, download resources.

You need to sign in to unlock your resources.

Everything's an Argument 8e to 9e Transition Guide

Everything's an argument 9e correlated to council of writing program administrators’ outcomes statement for first-year composition, instructor's notes for everything's an argument, sample course plans, using achieve with everything’s an argument with readings, 9e.

You've selected:

Click the E-mail Download Link button and we'll send you an e-mail at with links to download your instructor resources. Please note there may be a delay in delivering your e-mail depending on the size of the files.

Your download request has been received and your download link will be sent to .

Please note you could wait up to 30 to 60 minutes to receive your download e-mail depending on the number and size of the files. We appreciate your patience while we process your request.

Check your inbox, trash, and spam folders for an e-mail from [email protected] .

If you do not receive your e-mail, please visit macmillanlearning.com/support .

Related Titles

Select a demo to view:

We are happy to offer free Achieve access in addition to the physical sample you have selected. Sample this version now as opposed to waiting for the physical edition.

Argumentative Standards, Grades 9-10

(Adopted 2010)

Grades 9-10 | Common Core | Writing Standards

Text Types and Purposes

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.9-10.1.A: Introduce precise claim(s), distinguish the claim(s) from alternate or opposing claims, and create an organization that establishes clear relationships among claim(s), counterclaims, reasons, and evidence.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.9-10.1.B: Develop claim(s) and counterclaims fairly, supplying evidence for each while pointing out the strengths and limitations of both in a manner that anticipates the audience's knowledge level and concerns.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.9-10.1.C: Use words, phrases, and clauses to link the major sections of the text, create cohesion, and clarify the relationships between claim(s) and reasons, between reasons and evidence, and between claim(s) and counterclaims.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.9-10.1.D: Establish and maintain a formal style and objective tone while attending to the norms and conventions of the discipline in which they are writing.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.9-10.1.E: Provide a concluding statement or section that follows from and supports the argument presented.

Production and Distribution of Writing

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.9-10.4: Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience. (Grade-specific expectations for writing types are defined in standards 1-3 above.)

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.9-10.5: Develop and strengthen writing as needed by planning, revising, editing, rewriting, or trying a new approach, focusing on addressing what is most significant for a specific purpose and audience. (Editing for conventions should demonstrate command of Language standards 1-3 up to and including grades 9-10 here.)

Range of Writing

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.9-10.10: Write routinely over extended time frames (time for research, reflection, and revision) and shorter time frames (a single sitting or a day or two) for a range of tasks, purposes, and audiences.

(Adopted 2012)

Grades 9-10 | Alaska | Writing Standards

- W.9-10.1.a: Introduce precise claim(s), distinguish the claim(s) from alternate or opposing claims, and create an organization that establishes clear relationships among claim(s), counterclaims, reasons, and evidence.

- W.9-10.1.b: Develop claim(s) and counterclaims fairly, supplying evidence for each while pointing out the strengths and limitations of both in a manner that anticipates the audience’s knowledge level and concerns.