- Work & Careers

- Life & Arts

- Currently reading: Arundhati Roy: ‘The pandemic is a portal’ | Free to read

- Will America tear itself apart? The Supreme Court, 2020 elections and a looming constitutional crisis

- Loneliness and me

- Yuval Noah Harari: the world after coronavirus | Free to read

- America the beautiful: three generations in the struggle for civil rights | Free to read

- Splendid isolation: the long way home

- The rise and fall of the office

Arundhati Roy: ‘The pandemic is a portal’ | Free to read

- Arundhati Roy: ‘The pandemic is a portal’ | Free to read on x (opens in a new window)

- Arundhati Roy: ‘The pandemic is a portal’ | Free to read on facebook (opens in a new window)

- Arundhati Roy: ‘The pandemic is a portal’ | Free to read on linkedin (opens in a new window)

- Arundhati Roy: ‘The pandemic is a portal’ | Free to read on whatsapp (opens in a new window)

Arundhati Roy

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Who can use the term “gone viral” now without shuddering a little? Who can look at anything any more — a door handle, a cardboard carton, a bag of vegetables — without imagining it swarming with those unseeable, undead, unliving blobs dotted with suction pads waiting to fasten themselves on to our lungs?

Who can think of kissing a stranger, jumping on to a bus or sending their child to school without feeling real fear? Who can think of ordinary pleasure and not assess its risk? Who among us is not a quack epidemiologist, virologist, statistician and prophet? Which scientist or doctor is not secretly praying for a miracle? Which priest is not — secretly, at least — submitting to science?

And even while the virus proliferates, who could not be thrilled by the swell of birdsong in cities, peacocks dancing at traffic crossings and the silence in the skies?

The number of cases worldwide this week crept over a million . More than 50,000 people have died already. Projections suggest that number will swell to hundreds of thousands, perhaps more. The virus has moved freely along the pathways of trade and international capital, and the terrible illness it has brought in its wake has locked humans down in their countries, their cities and their homes.

But unlike the flow of capital, this virus seeks proliferation, not profit, and has, therefore, inadvertently, to some extent, reversed the direction of the flow. It has mocked immigration controls, biometrics, digital surveillance and every other kind of data analytics, and struck hardest — thus far — in the richest, most powerful nations of the world, bringing the engine of capitalism to a juddering halt. Temporarily perhaps, but at least long enough for us to examine its parts, make an assessment and decide whether we want to help fix it, or look for a better engine.

The mandarins who are managing this pandemic are fond of speaking of war. They don’t even use war as a metaphor, they use it literally. But if it really were a war, then who would be better prepared than the US? If it were not masks and gloves that its frontline soldiers needed, but guns, smart bombs, bunker busters, submarines, fighter jets and nuclear bombs, would there be a shortage?

Night after night, from halfway across the world, some of us watch the New York governor ’s press briefings with a fascination that is hard to explain. We follow the statistics, and hear the stories of overwhelmed hospitals in the US, of underpaid, overworked nurses having to make masks out of garbage bin liners and old raincoats, risking everything to bring succour to the sick. About states being forced to bid against each other for ventilators, about doctors’ dilemmas over which patient should get one and which left to die. And we think to ourselves, “My God! This is America !”

The tragedy is immediate, real, epic and unfolding before our eyes. But it isn’t new. It is the wreckage of a train that has been careening down the track for years. Who doesn’t remember the videos of “patient dumping” — sick people, still in their hospital gowns, butt naked, being surreptitiously dumped on street corners? Hospital doors have too often been closed to the less fortunate citizens of the US. It hasn’t mattered how sick they’ve been, or how much they’ve suffered.

At least not until now — because now, in the era of the virus, a poor person’s sickness can affect a wealthy society’s health. And yet, even now, Bernie Sanders, the senator who has relentlessly campaigned for healthcare for all, is considered an outlier in his bid for the White House, even by his own party.

The tragedy is the wreckage of a train that has been careening down the track for years

And what of my country, my poor-rich country, India, suspended somewhere between feudalism and religious fundamentalism, caste and capitalism, ruled by far-right Hindu nationalists?

In December, while China was fighting the outbreak of the virus in Wuhan, the government of India was dealing with a mass uprising by hundreds of thousands of its citizens protesting against the brazenly discriminatory anti-Muslim citizenship law it had just passed in parliament.

The first case of Covid-19 was reported in India on January 30, only days after the honourable chief guest of our Republic Day Parade, Amazon forest-eater and Covid-denier Jair Bolsonaro , had left Delhi. But there was too much to do in February for the virus to be accommodated in the ruling party’s timetable. There was the official visit of President Donald Trump scheduled for the last week of the month. He had been lured by the promise of an audience of 1m people in a sports stadium in the state of Gujarat. All that took money, and a great deal of time.

Then there were the Delhi Assembly elections that the Bharatiya Janata Party was slated to lose unless it upped its game, which it did, unleashing a vicious, no-holds-barred Hindu nationalist campaign, replete with threats of physical violence and the shooting of “traitors”.

It lost anyway. So then there was punishment to be meted out to Delhi’s Muslims, who were blamed for the humiliation. Armed mobs of Hindu vigilantes, backed by the police, attacked Muslims in the working-class neighbourhoods of north-east Delhi. Houses, shops, mosques and schools were burnt. Muslims who had been expecting the attack fought back. More than 50 people, Muslims and some Hindus, were killed.

Thousands moved into refugee camps in local graveyards. Mutilated bodies were still being pulled out of the network of filthy, stinking drains when government officials had their first meeting about Covid-19 and most Indians first began to hear about the existence of something called hand sanitiser.

March was busy too. The first two weeks were devoted to toppling the Congress government in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh and installing a BJP government in its place. On March 11 the World Health Organization declared that Covid-19 was a pandemic. Two days later, on March 13, the health ministry said that corona “is not a health emergency”.

Finally, on March 19, the Indian prime minister addressed the nation. He hadn’t done much homework. He borrowed the playbook from France and Italy. He told us of the need for “social distancing” (easy to understand for a society so steeped in the practice of caste) and called for a day of “people’s curfew” on March 22. He said nothing about what his government was going to do in the crisis, but he asked people to come out on their balconies, and ring bells and bang their pots and pans to salute health workers.

He didn’t mention that, until that very moment, India had been exporting protective gear and respiratory equipment, instead of keeping it for Indian health workers and hospitals.

Not surprisingly, Narendra Modi’s request was met with great enthusiasm. There were pot-banging marches, community dances and processions. Not much social distancing. In the days that followed, men jumped into barrels of sacred cow dung, and BJP supporters threw cow-urine drinking parties. Not to be outdone, many Muslim organisations declared that the Almighty was the answer to the virus and called for the faithful to gather in mosques in numbers.

On March 24, at 8pm, Modi appeared on TV again to announce that, from midnight onwards, all of India would be under lockdown . Markets would be closed. All transport, public as well as private, would be disallowed.

He said he was taking this decision not just as a prime minister, but as our family elder. Who else can decide, without consulting the state governments that would have to deal with the fallout of this decision, that a nation of 1.38bn people should be locked down with zero preparation and with four hours’ notice? His methods definitely give the impression that India’s prime minister thinks of citizens as a hostile force that needs to be ambushed, taken by surprise, but never trusted.

Locked down we were. Many health professionals and epidemiologists have applauded this move. Perhaps they are right in theory. But surely none of them can support the calamitous lack of planning or preparedness that turned the world’s biggest, most punitive lockdown into the exact opposite of what it was meant to achieve.

The man who loves spectacles created the mother of all spectacles.

As an appalled world watched, India revealed herself in all her shame — her brutal, structural, social and economic inequality, her callous indifference to suffering.

The lockdown worked like a chemical experiment that suddenly illuminated hidden things. As shops, restaurants, factories and the construction industry shut down, as the wealthy and the middle classes enclosed themselves in gated colonies, our towns and megacities began to extrude their working-class citizens — their migrant workers — like so much unwanted accrual.

Many driven out by their employers and landlords, millions of impoverished, hungry, thirsty people, young and old, men, women, children, sick people, blind people, disabled people, with nowhere else to go, with no public transport in sight, began a long march home to their villages. They walked for days, towards Badaun, Agra, Azamgarh, Aligarh, Lucknow, Gorakhpur — hundreds of kilometres away. Some died on the way.

Our towns and megacities began to extrude their working-class citizens like so much unwanted accrual

They knew they were going home potentially to slow starvation. Perhaps they even knew they could be carrying the virus with them, and would infect their families, their parents and grandparents back home, but they desperately needed a shred of familiarity, shelter and dignity, as well as food, if not love.

As they walked, some were beaten brutally and humiliated by the police, who were charged with strictly enforcing the curfew. Young men were made to crouch and frog jump down the highway. Outside the town of Bareilly, one group was herded together and hosed down with chemical spray.

A few days later, worried that the fleeing population would spread the virus to villages, the government sealed state borders even for walkers. People who had been walking for days were stopped and forced to return to camps in the cities they had just been forced to leave.

Among older people it evoked memories of the population transfer of 1947, when India was divided and Pakistan was born. Except that this current exodus was driven by class divisions, not religion. Even still, these were not India’s poorest people. These were people who had (at least until now) work in the city and homes to return to. The jobless, the homeless and the despairing remained where they were, in the cities as well as the countryside, where deep distress was growing long before this tragedy occurred. All through these horrible days, the home affairs minister Amit Shah remained absent from public view.

When the walking began in Delhi, I used a press pass from a magazine I frequently write for to drive to Ghazipur, on the border between Delhi and Uttar Pradesh.

The scene was biblical. Or perhaps not. The Bible could not have known numbers such as these. The lockdown to enforce physical distancing had resulted in the opposite — physical compression on an unthinkable scale. This is true even within India’s towns and cities. The main roads might be empty, but the poor are sealed into cramped quarters in slums and shanties.

Every one of the walking people I spoke to was worried about the virus. But it was less real, less present in their lives than looming unemployment, starvation and the violence of the police. Of all the people I spoke to that day, including a group of Muslim tailors who had only weeks ago survived the anti-Muslim attacks, one man’s words especially troubled me. He was a carpenter called Ramjeet, who planned to walk all the way to Gorakhpur near the Nepal border.

“Maybe when Modiji decided to do this, nobody told him about us. Maybe he doesn’t know about us”, he said.

“Us” means approximately 460m people.

State governments in India (as in the US) have showed more heart and understanding in the crisis. Trade unions, private citizens and other collectives are distributing food and emergency rations. The central government has been slow to respond to their desperate appeals for funds. It turns out that the prime minister’s National Relief Fund has no ready cash available. Instead, money from well-wishers is pouring into the somewhat mysterious new PM-CARES fund. Pre-packaged meals with Modi’s face on them have begun to appear.

In addition to this, the prime minister has shared his yoga nidra videos, in which a morphed, animated Modi with a dream body demonstrates yoga asanas to help people deal with the stress of self-isolation.

The narcissism is deeply troubling. Perhaps one of the asanas could be a request-asana in which Modi requests the French prime minister to allow us to renege on the very troublesome Rafale fighter jet deal and use that €7.8bn for desperately needed emergency measures to support a few million hungry people. Surely the French will understand.

As the lockdown enters its second week, supply chains have broken , medicines and essential supplies are running low. Thousands of truck drivers are still marooned on the highways, with little food and water. Standing crops, ready to be harvested, are slowly rotting.

The economic crisis is here. The political crisis is ongoing. The mainstream media has incorporated the Covid story into its 24/7 toxic anti-Muslim campaign. An organisation called the Tablighi Jamaat, which held a meeting in Delhi before the lockdown was announced, has turned out to be a “super spreader”. That is being used to stigmatise and demonise Muslims. The overall tone suggests that Muslims invented the virus and have deliberately spread it as a form of jihad.

The Covid crisis is still to come. Or not. We don’t know. If and when it does, we can be sure it will be dealt with, with all the prevailing prejudices of religion, caste and class completely in place.

Today (April 2) in India, there are almost 2,000 confirmed cases and 58 deaths. These are surely unreliable numbers, based on woefully few tests. Expert opinion varies wildly. Some predict millions of cases. Others think the toll will be far less. We may never know the real contours of the crisis, even when it hits us. All we know is that the run on hospitals has not yet begun.

India’s public hospitals and clinics — which are unable to cope with the almost 1m children who die of diarrhoea, malnutrition and other health issues every year, with the hundreds of thousands of tuberculosis patients (a quarter of the world’s cases), with a vast anaemic and malnourished population vulnerable to any number of minor illnesses that prove fatal for them — will not be able to cope with a crisis that is like what Europe and the US are dealing with now.

All healthcare is more or less on hold as hospitals have been turned over to the service of the virus. The trauma centre of the legendary All India Institute of Medical Sciences in Delhi is closed, the hundreds of cancer patients known as cancer refugees who live on the roads outside that huge hospital driven away like cattle.

People will fall sick and die at home. We may never know their stories. They may not even become statistics. We can only hope that the studies that say the virus likes cold weather are correct (though other researchers have cast doubt on this). Never have a people longed so irrationally and so much for a burning, punishing Indian summer.

What is this thing that has happened to us? It’s a virus, yes. In and of itself it holds no moral brief. But it is definitely more than a virus. Some believe it’s God’s way of bringing us to our senses. Others that it’s a Chinese conspiracy to take over the world.

Whatever it is, coronavirus has made the mighty kneel and brought the world to a halt like nothing else could. Our minds are still racing back and forth, longing for a return to “normality”, trying to stitch our future to our past and refusing to acknowledge the rupture. But the rupture exists. And in the midst of this terrible despair, it offers us a chance to rethink the doomsday machine we have built for ourselves. Nothing could be worse than a return to normality.

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next.

We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.

Arundhati Roy ’s latest novel is ‘The Ministry of Utmost Happiness’

Copyright © Arundhati Roy 2020

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Listen to our podcast, Culture Call , where FT editors and special guests discuss life and art in the time of coronavirus. Subscribe on Apple , Spotify , or wherever you listen.

Letter in response to this article:

Indian government must support the apparel sector / From Rajendra Aneja, Aneja Management Consultants, Mumbai, India

Promoted Content

Explore the series.

Follow the topics in this article

- Life & Arts Add to myFT

- Coronavirus Add to myFT

- India Add to myFT

- Arundhati Roy Add to myFT

International Edition

- Fellowships

Covering thought leadership in journalism

Live @ Lippmann

February 26, 2021.

Arundhati Roy: “We Live in an Age of Mini-Massacres”

The man booker prize-winning author of “the god of small things” on the state of india’s democracy, violence against women and minorities, the role of the media, and more.

Internationally acclaimed author and activist Arundhati Roy speaks during a press conference, where the panel condemned the criminalization of the right to peaceful public protest in a democracy, in New Delhi in October 2020 Mayank Makhija/NurPhoto via AP

Arundhati Roy’s first novel, “The God of Small Things,” won the Man Booker Prize in 1997. Her second, “The Ministry of Utmost Happiness,” was shortlisted for it. These books, written two decades apart, capture how India has changed. In addition to her fiction, though, Roy’s political essays taught a generation of young Indian writers to think incendiary thoughts. Her recent New Yorker profile says her essays on India ’ s nuclear policies are not so much written as breathed out in a stream of fire.

Years of increasing repression towards journalists from Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government have come to a head in recent weeks , as the country is roiled by the ongoing farmers’ protest against three farm bills passed in September 2020. Numerous journalists reporting on the protests have faced criminal charges and, in early February, some 100 journalists, publications, and activists were temporarily blocked by Twitter at the request of India’s Ministry and Electronics and Information Technology.

Related Reading

In India, Journalists “Are Fighting For Whether Truth is Meaningful or Not” By Madeleine Schwartz

At a time when democratic values are under siege in her home country of India, as they are elsewhere around the world, including in the U.S., Roy’s analysis of issues like nuclear weapons, industrialization, nationalism, and more is essential to this moment. She is unapologetic about the stakes. Once, when a historian criticized her for passionate rhetoric, she responded, “I am hysterical. I’m screaming from the bloody rooftops … I want to wake the neighbors. That ’ s my whole point. I want everybody to open their eyes.”

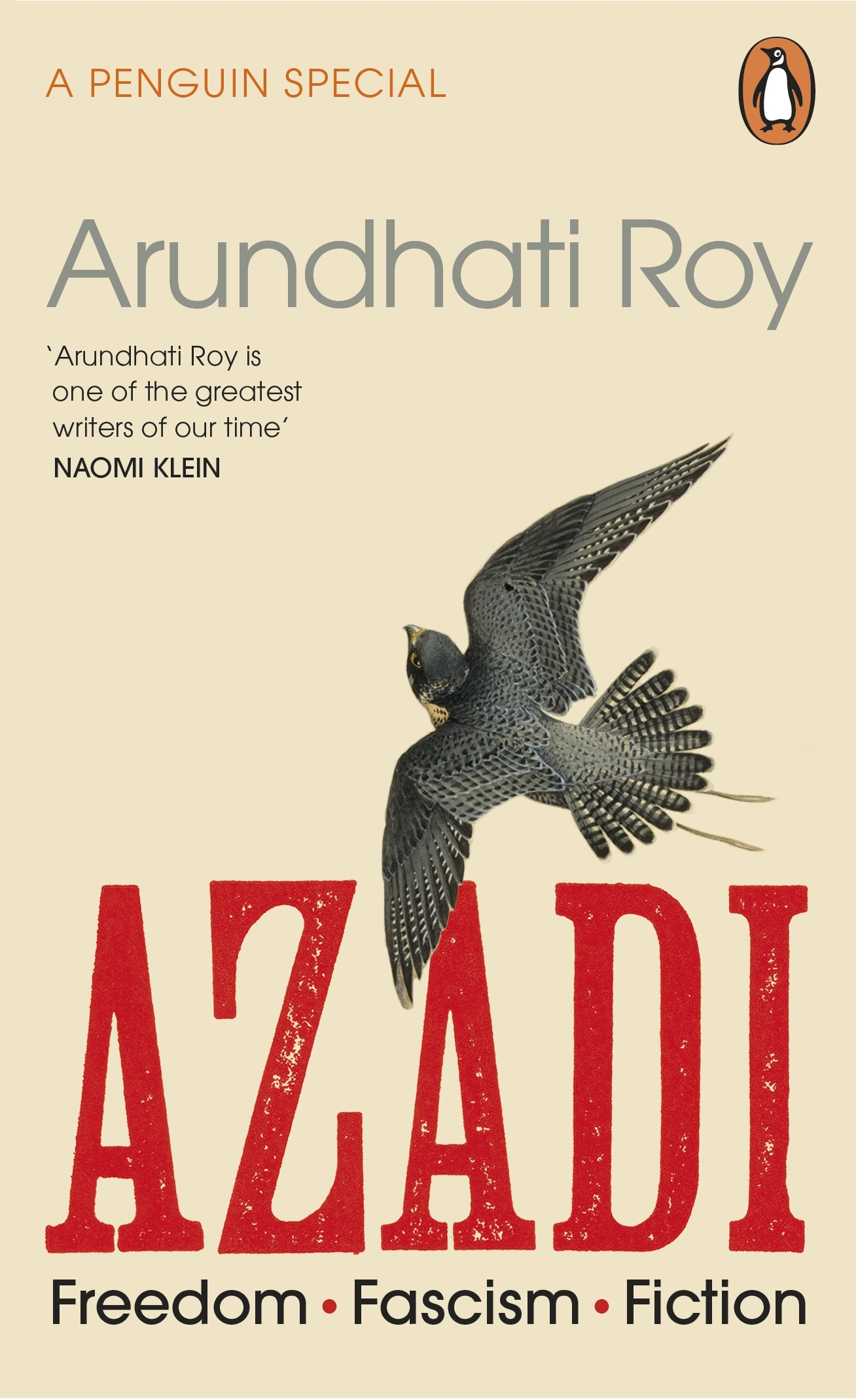

Roy’s work has been translated into more than 45 languages and, in 2019, her nonfiction was collected in a single volume, “ My Seditious Heart .” A new collection of essays, “ Azadi: Freedom. Fascism. Fiction. ” was published last year. Roy spoke with the Nieman Foundation and shared her thoughts with Nieman Reports in February. Edited excerpts:

On whether India can still be called a democracy

Of course not. Apart from the laws that exist, like the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act [1967 anti-terrorism legislation to prevent unlawful activities and associations and “maintain the sovereignty and integrity of India”], under which you have hundreds of people now just being picked up and put into jail every day, apart from that fact, every institution that is meant to work as a check against unaccountable power is seriously compromised.

Also, the elections are compromised. I don’t think we have free and fair elections because you have a system now of secret electoral bonds, which allows business corporations to secretly fund political parties. We have today a party that is the richest political party in the world, the BJP. Elections in India have become a spectator sport — it’s like watching a Ferrari racing a few old bicycles.

In any case, a democracy doesn’t mean just elections. First of all, India hasn’t been a democracy in Kashmir. It hasn’t been a democracy in Bastar [a district in the state of Chhattisgarh in central India]. It hasn’t been a democracy for the poorest of the poor who have no access to institutions of justice, who live completely under the boot of police and the justice system that crushes them with violence and indifference.

Now the oxygen is being taken away, sucked out of the lungs of even the middle class and even the big farmers, the agricultural elite.

On violence against women and Dalit and Muslim citizens, including lynchings of minorities by Hindu nationalist mobs

The thing is that when it comes to women, the fact that the caste system exists has meant that dominant castes in many many villages in India still feel that they have the right to oppressed caste woman’s body. That is how it has been traditionally.

This is why in India only certain rapes create outrage, whereas others are accepted as part of how things go. Look at what has happens to women in the northeastern states—Manipur for example, or women in Kashmir. Places that are literally administered by the security forces. You can imagine what goes on with that kind of imbalance of power. But the outrage doesn’t manifest itself on India’s streets. So you ’ re left wondering which rapes are considered outrageous in a society like this, and which are not.

When people feel that they have a license to lynch — permission from the top, then the reasons for lynching are not just to keep a community in fear. A whole ecosystem of fear kicks in, and not just fear, bullying, avarice — how one set of people can gain advantage over another — by frightening them , chasing them away from their land, from their villages. There’s a kind of lynching economy also that establishes itself through all this. We live in an age of mini-massacres. Very atomized, localized. You don’t need the old-style mega massacres like Gujarat 2002 or Mumbai 1993 any more.

The most dangerous thing that has happened is that, [as] the last few elections have shown, the BJP has proved that it can win elections without the Muslim vote. That creates a situation, where you have a minority which actually is made up of millions of people who are virtually disenfranchised. That’s a very, very dangerous situation.

On the role the media has played in the decline of India’s democracy

None of this could have happened if it wasn’t the media. Here you see the confluence of corporate money, corporate advertisement, and this vicious nationalism. You can’t even call them media or journalists anymore. It would be wrong.

The only [legitimate] media that there is now is a few people who are online who are managing very bravely to carry on and a few magazines like Caravan. I was recently listening to a very moving talk by this young journalist called Mandeep Punia who had just been arrested and beaten up. He was talking about how so many of his fellow journalists cannot be called journalists any more.

They’re just people who act out a script every day. If you look at the media, the police — I’m sorry to say this, but it’s almost diseased. I keep joking that I can’t put on the TV in my house because it feels like that girl in “The Exorcist,” this green bile pouring forth from the TV screen and spilling onto the floor. I feel like I need to clean it up. I don’t put it on anymore.

On the role of the writer or the artist in democracies in crisis

I often think that writers are no different from plumbers or carpenters. Some service the fascists. Some service the others. It’s not that writers are in any way politically better people. You see plenty of writers completely being part of this Hindu fascist project.

It’s been a question that’s very interesting to me for as long as I’ve ever been a writer. During the Freedom struggle against the British it was easy to delineate the battle., “The colonizer’s bad and they’re white. The freedom fighters are local, and they’re brown.” There’s a way in which passions could be comparatively at least, clear. Now, it’s all so murky. The river’s full of mud and silt.

To me, it’s always been the case that I feel like you need to have eyes around your head. For example, if you look at what’s happening with the farm protests now, how do you understand it, as a writer or as a human being? The government is under pressure because it’s the first time they’re faced with people who have not necessarily always been their ideological opponent. It’s hard to portray farmers as terrorists and anti-nationals, though God knows they’ve tried.

The agriculture crisis is a real crisis. It wasn’t created by Hindu fundamentalism. It was created by the Green Revolution when capital-intensive farming was introduced. It was created by the over‑mining of water, by the over-use of pesticides, by hybrid seeds, by putting in massive irrigation projects and not thinking about how to drain the water. So how do I make literature out of irrigation problems, or drainage, or electricity?

It’s been something that I’ve been pretty obsessed with, understanding things which are not normally considered a fiction writer’s business. To me, I can’t write fiction unless I make it my business.You have to know how all these things intersect with each other. How does caste, or race, or class, or irrigation, or bore-wells affect what might seem like a clash between two communities? How does the harnessing of rivers in Kashmir affect that conflict?

On the writing process

I am a structure nerd myself. A lot of it does have to do with the fact that I studied architecture, the fact that I am very and always have been very interested in cities and how they are structured and how they work, and how institutions in the city are built for citizens, and the non‑citizens live in the cracks.

To me, if you look at my fiction or the non‑fiction, even almost every non‑fiction essay, it is a story. It seems to be the only way I can explain things to myself. There is a mathematics to the way the structure works. In fiction, to me, the structure and the language is as important as the story or the characters.

I don’t think I’m capable of writing something from A to B. It has to take a walk around the park, and then come back to certain places, and then have these reference points. Whether it’s “The God of Small Things” or “The Ministry of Utmost Happiness,” structure’s everything.

On the dangers to journalists, intellectuals, and activists in India

The thing is, what we first have to understand is how ordinary people — ordinary villagers, indigenous people, women guerillas who’ve been fighting mining corporations, people whose names we don’t know — have been dragged into prison, have been humiliated, even sexually humiliated. Those who have humiliated them have been given bravery awards. Look at the number who have been imprisoned, executed, buried in mass graves in Kashmir. All that violence that many Indians have accepted quite comfortably, even approved of, has now arrived at their doorsteps.

When you’re a journalist, a writer, anybody whose head is above the water, you’re already privileged in terms of someone’s looking out for you. You have a lawyer. Meanwhile, we have thousands of people who are in prison who don’t have any access to legal help, nothing.

Then you have a situation where, I’d say, the best of the best — I mean journalists, trade unionists, lawyers who defend them — are in jail. We know a lot of them are in jail for entirely made‑up reasons. There are students in jail. The latest police trick is to make a charge-sheet that is 17,000 pages, 30,000 pages. You’d need a whole bloody library shelf in your prison cell to accommodate your own charge-sheet.

A lawyer or a judge can’t even read it, let alone adjudicate upon it, for years maybe. They are continuously arresting people, or threatening people with arrest. The harassment, even if you are not actually in prison is unbelievable. Your life comes to a standstill. And once people are jailed then the ones who aren’t spend all their time running to lawyers, attending court hearings…The other trick is to have non-internet trolls file cases against you in many cities and towns. Then you spend your time running around. Who can afford it? Who can hold a job if they have to worry about court appearances?

This kinds of harassment flourishes because institutions in India are dominated by Hindutva apparatchiks, it’s really, really worrying. Of course, now, there seems to be a pretty focused attack on women, young women, women activists.

The Chief Justice recently said, “Why are women being kept in the protests?” He’s talking about women who are the backbone of the farming world. Why are they being “kept” in protests?

On the role of tech platforms

Initially, when the 2002 Gujarat pogrom [in which a Godhra train burning that killed nearly 60 Hindu pilgrims incited three days of inter-communal violence in the western state of Gujarat, resulting in more than 1,000 deaths] happened, in fact, for a whole set of reasons, Narendra Modi was banned from travelling to the U.S. A lot of activist groups had successfully campaigned to have him banned. When he became prime minister, that ban was removed.

As I said, at that time, India was at the time a very attractive finance destination. Today, that’s less true but then India is seen as the region that is going to be the bulwark against China and Chinese expansionism. So it’s going to be given a broad pass for these strategic reasons.

The role of big tech is interesting because from 2014 and pre‑2014, let’s say a few years before that, right up to now, the Hindu nationalists had figured out how to use social media to their advantage. You have these things called WhatsApp farms. You have trolls. You have disinformation and lies. All of it spreading like a bushfire.

But recently, you see that the other side has begun to gear up and fight back. Now, there’s a lot of tension on social media and the fact is that, in Kashmir, when 370 was abrogated [revoking the limited autonomy, or “special status,” of the Jammu and Kashmir region], you had an Internet ban that lasted for months and months. The Internet has been banned on the borders of Delhi. The Internet has been banned all over the place.

It should be considered a human rights violation, legally and properly. A crime against humanity actually — if you look closely at the consequences of an almost year-long ban. You cannot, on the one hand, push the entire country into digital transactions, unique IDs, Aadhar cards, iris scans, and then ban the Internet.

You have that situation right now where all of us are being pushed into some form of radical digital transparency, while the only thing that’s opaque is how elections are funded and how political parties make their money and keep their money secret.

On what gives hope

I’m not that fairy princess who’s going to hold out this false hope. I have days of utter desolation and hopelessness, of course I do, like millions of others here. But the fact is that when we develop a way of thinking and a way of seeing, we end up, many of us, certainly me, being people who know that we’ve got to do what we have to do. Whether we win or lose, we’re going to do it because we’re never going to go over to the other side.

You’ve got to keep holding on to that, because that is what puts the oxygen in our lungs, that way of thinking, that way of writing, that way of not aggrandizing yourself to an extent where you think you can solve all the world’s problems. You can’t, but you can do something. And so you just keep doing that something.

In the most stressful situations, whether it’s in the forest where I spent some time with the armed guerrillas in Bastar, or whether it’s friends in Kashmir, or whether it’s in the deepest, darkest places, there’s always humanity. There’s always humor. There’s always literature. There’s always music. There’s always something beautiful.

That’s life. There isn’t ever going to be an end to the chaos. Everything is never going to work out just fine. It’s not going to happen. But we have to be able to accommodate that chaos in our minds and be part of it, swim with it, absorb it, influence it, turn it to our purpose. The wind will change direction at some point, won’t it?

Further Reading

In india, journalists “are fighting for whether truth is meaningful or not”, by madeleine schwartz, international reporting must distinguish hindu nationalism from hinduism, by kalpana jain, amidst crackdowns, kashmiri journalists struggle to report, by toufiq rashid.

- Register / Login

- International

- Photo Stories

- Interactives

- Himachal Pradesh

- Jammu and Kashmir

- Madhya Pradesh

- Uttar Pradesh

- Uttarakhand

- Andhra Pradesh

- Chhattisgarh

- West Bengal

- Maharashtra

- Arunachal Pradesh

- Entertainment

- Election 2019

- Assam Elections 2021

- Assembly Elections 2023

- Elections 2024

- Elections - Interactives

- World Cup 2023

- Budget 2023

- Flight Insight

- Economy Series

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Brand studio

Arundhati Roy: How a novel symbolises freedom and essay ‘a form of combat’

To arundhati roy, winner of the 2023 european essay prize, a novel is ‘real, unfettered azadi’. and essay a tool to fight against fascism and injustice..

When Arundhati Roy was thinking of the title of her 2020 collection of essays, AZADI: Freedom. Fascism. Fiction (Penguin India), which recently earned her the 2023 European Essay Prize, her publisher in the UK, Simon Prosser, asked her what she thought of when she thought of azadi (freedom). “I surprised myself by answering, without a moment’s hesitation, ‘A novel.’ Because a novel gives a writer the freedom to be as complicated as she wants — to move through worlds, languages, and time, through societies, communities, and politics,” she writes in the introduction to the book, a compilation of her lectures and essays written between 2018 and 2020, described by the publisher as “a pressing dispatch from the heart of the crowd and the solitude of a writer’s desk.”

In analysing the essence of a novel, Roy (61) posits that its complexity and intricacy should not be confused with it being ‘loose, baggy, or random’. “A novel, to me, is freedom with responsibility. Real, unfettered azadi” , she writes, pointing out how azadi , the slogan of the ‘freedom struggle’ in Kashmir, has also become a chant of millions against the project of Hindu nationalism. While some essays in the volume have been written through the lens of a novelist delving into the very universe of her novels, others explore the symbiotic relationship between fiction and reality, shining light on how fiction seamlessly integrates into the world and, in many ways, becomes the world itself. Like it does in her two novels: the lyrical and exquisitely written The God of Small Things (1997), for which she received the Booker Prize, and her long-awaited second work of fiction, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness (2017) .

Charles Veillon Foundation, the instituting body that confers the prize, said in a statement, ‘Roy uses the essay as a form of combat.’ The publication of The God of Small Things coincided with the 50th anniversary of India’s independence from British colonialism. This period marked India’s pivot toward the global stage, during which the country aligned itself with the United States, embracing corporate capitalism, privatisation, and structural adjustments. However, a shift occurred the Indian political landscape in 1998 with the ascent of a BJP-led Hindu nationalist government, which conducted nuclear tests, altering the public discourse dramatically.

Roy, who had just won the Booker Prize, found herself thrust into the role of a cultural ambassador for the emerging New India. She began her journey of speaking out through her writing lest her silence was seen as complicity. Her powerful essay, ‘The End of Imagination’, which rails against the nuclear weapons as an affirmation of statehood, identity and defence, led to her being labelled ‘a traitor and anti-national’. However, she took these insults as badges of honour, realising well that speaking out was a political act in itself. In her subsequent essays, she wrote about dams, rivers, displacement, caste, mining, and civil war.

Literature and freedom

In her acceptance speech, Roy articulated her perspective on the notion of freedom. She made it clear that her happiness, as a writer, stems from the world of literature and the craft of writing. Over the past 25 years, she has penned essays that serve as a warning about the direction the country has been headed. Yet, these warnings have often fell on deaf ears, with liberals and self-proclaimed progressives often dismissing her writing. “But now the time for warning is over. We are in a different phase of history. As a writer, I can only hope that my writing will bear witness to this very dark chapter that is unfolding in my country’s life. And hopefully, the work of others like myself lives on, it will be known that not all of us agreed with what was happening,” she said.

Ahead of the 2024 General elections, Roy fears that if Narendra Modi comes back to power, there might be a new Constitution which will only curtail her ability to speak candidly. The irony lies in the fact that she receives the prize for her work, which essentially forewarned the country about its current trajectory. Much of her first essay, written for the W. G. Sebald Lecture on Literary Translation which she delivered in the British Library in London in June 2018, is about the divisive partitioning of Hindustani into Hindi and Urdu, a schism that eerily foreshadowed the rise of Hindu Nationalism in India by more than a century. She delves into the historical roots of a project that would later reshape India’s political landscape. Scathing and incisive and trenchant and courageous and piercing and perspicacious — words that have come to define her style — these essays reflect the collective hopes, fears and despair of the people of India, minus the saffron brigade.

The early essays reflect the hope that many of us had in 2018: that Modi's reign would come to an end. “As the 2019 general election approached, polls showed Modi and his party’s popularity dropping dramatically. We knew this was a dangerous moment. Many of us anticipated a false-flag attack or even a war that would be sure to change the mood of the country,” she writes. In one of the essays, “Election Season in a Dangerous Democracy” (2018) she also underscores this fear: “We held our collective breath. In February 2019, weeks before the general election, the attack came. A suicide bomber blew himself up in Kashmir, killing forty security personnel. False flag or not, the timing was perfect. Modi and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) swept back to power.”

As she was writing the introduction to the book in February 2020, then US President Donald Trump was on an official visit to India, and the first case of COVID-19 had been reported. It was a time when India was grappling with the revocation of Jammu and Kashmir’s special status, widespread protests against an anti-Muslim citizenship law, and the horrifying communal violence in Delhi. “In a public speech to a crowd wearing Modi and Trump masks, Donald Trump informed Indians that they play cricket, celebrate Diwali, and make Bollywood films. We were grateful to learn that about ourselves. Between the lines he sold us MH-60 helicopters worth $3 billion. Rarely has India publicly humiliated herself thus,” she writes.

Literature in the Dark Times

Roy uses her words as both a shield and a sword in the face of an increasingly polarised world. In an essay titled ‘The Language of Literature,’ she grapples with the state of the world, dissecting the impact of capitalism, war, and government policies on our planet and its people. She doesn’t mince words when pointing out that much of the blame for the global chaos rests on the shoulders of the United States. She writes how after 17 years of the US invasion of Afghanistan, the conflict led to negotiations with the very Taliban they sought to overthrow. In the interim, Iraq, Libya, and Syria fell victim to the chaos of war, causing countless casualties and turning ancient cities into ruins. The rise of groups like Daesh (ISIS) further added to the turmoil. In her characteristic candour, she describes the US as ‘a rogue state’ that flouts international treaties and engages in aggressive rhetoric.

Roy believes that the place for literature is not predefined but rather built by writers and readers. It’s a fragile yet indestructible sanctuary that provides shelter in the face of chaos. She values the idea of literature that is necessary, literature that offers refuge: “It’s a fragile place in some ways, but an indestructible one. When it’s broken, we rebuild it. Because we need shelter. I very much like the idea of literature that is needed. Literature that provides shelter. Shelter of all kinds.” Her own journey as a writer has seen her straddle the worlds of fiction and nonfiction, with no clear boundary between the two.

She rejects the notion that fiction and nonfiction are at odds, stating that both are equally true, equally real, and equally significant: “I have never felt that my fiction and nonfiction were warring factions battling for suzerainty. They aren’t the same certainly, but trying to pin down the difference between them is actually harder than I imagined. Fact and fiction are not converse. One is not necessarily truer than the other, more factual than the other, or more real than the other. Or even, in my case, more widely read than the other. All I can say is that I feel the difference in my body when I’m writing.”

Acknowledging the risks that writers face today, she speaks of the perilous position of journalists in India, where threats to free expression have led to the country’s ranking just below conflict zones like Afghanistan and Syria. In The Ministry of Utmost Happiness , she navigates a complex map of languages, reflecting the linguistic diversity and complexity of India. She delves into the stories of characters who speak different tongues, showing how language can be both a bridge and a barrier. Her characters’ experiences demonstrate the challenges of living in a multilingual society, where slogans and chants may be in languages that people neither speak nor understand. Yet, they become tools of both resistance and assimilation.

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness , she writes, can be read as a conversation between two graveyards: “One is a graveyard where a hijra, Anjum — raised as a boy by a Muslim family in the walled city of Delhi — makes her home and gradually builds a guest house, the Jannat (Paradise) Guest House, and where a range of people come to seek shelter. The other is the ethereally beautiful valley of Kashmir, which is now, after thirty years of war, covered with graveyards, and in this way has become, literally, almost a graveyard itself. So, a graveyard covered by the Jannat Guest House, and a Jannat covered with graveyards. This conversation, this chatter between two graveyards, is and always has been strictly prohibited in India. In the real world, all conversation about Kashmir with the exception of Indian Government propaganda, is considered a high crime — treasonous even. Fortunately, in fiction, different rules apply.”

Similar Posts

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

The end of imagination

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

140 Previews

8 Favorites

Better World Books

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station50.cebu on February 10, 2022

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

Published August 22nd, 2022

The Ministress of the Political Essay — A Review of Arundhati Roy’s "Azadi"

by Sam Dapanas

In her 2020 collection of essays, Indian novelist, activist and essayist Arundhati Roy takes up questions of language, cultural belonging, literature and politics, up to the 2020 COVID pandemic. While taking the form of political essays, a form of writing with a long tradition in the English language, Roy’s pieces weave in and out of genres, chasing hard questions and suggesting provocative answers, in a never-ending confrontation between the colonial legacy of the Empire and the rich and multi-faceted identities of post-colonial countries.

I first read Arundhati Roy in a postcolonial literature class as an undergraduate English major, thanks to my Asianist professor back then who is a dramaturgist, theater director, and cultural studies scholar. Despite the grueling experience of reading The God of Small Things ’ first 100 pages (god, yes it was!), I loved it so much that I wrote a lengthy book review — one of the class’s final requirements — about it. Years later, her second novel would come out. I bought one of the first copies that arrived at the local bookstore. Reading Arundhati Roy’s nonfiction and essays in Azadi (which means ‘freedom’ in several Persian languages) and in My Seditious Heart: Collected Nonfiction (2019), I must say it made me understand further where the characters from her fiction, some nitpicked from real people in her life, are coming from. “In What Language Does Rain Fall In Tormented Cities?” the essay, a homage to a line from Pablo Neruda’s Libro de Preguntas (or The Book of Questions ), which serves as the first chapter of Azadi: Fascism, Freedom, Fiction , Roy gives us a glimpse of her creative process, pre- and post-writing, behind The Ministry of Utmost Happiness , her second novel, which was published in 2017.

Said piece was possibly the essay that stroke the strongest chord in me and that had resonance in me as a reader. Coming from a multilingual, if not translingual, community — outside the capital Manila, a typical Filipino child would learn English and (Tagalog-based) Filipino in school and the media, the native tongue at home, and because of the well-intentioned, poorly executed Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education (MTB MLE) policy, possibly another non-Tagalog language taught in school if one’s mother language is not the same dominant one in the region where one lives in — I know exactly the ‘slow violence’ of linguistic genocide. Perhaps as a rumination on her case, Roy wrote:

I fell to wondering what my mother tongue actually was. What was — is — the politically correct, culturally apposite, and morally appropriate language in which I ought to think and write? It occurred to me that my mother was actually an alien, with fewer arms than Kali perhaps but many more tongues. English is certainly one of them. My English has been widened and deepened by the rhythms and cadences of my alien mother’s other tongues. I say alien because there’s not much that is organic about her. Her nation-shaped body was first violently assimilated and then violently dismembered by an imperial British quill. I also say alien because the violence unleashed in her name on those who do not wish to belong to her (Kashmiris, for example), as well as on those who do (Indian Muslims and Dalits, for example), makes her an extremely unmotherly mother.

In A Brief History of the Political Essay , David Bromwich, himself a scholar of Western literary and philosophical canon, locates the political essay within the Euro-American tradition, from Jonathan Swift’s satires to Virginia Woolf’s memoirs, as having “never been a clearly defined genre.” Never been . A body of writings across cultures and eras exists but there is no strict definition of what works are confined within it and what works on the outside are not. But in Azadi, Arundhati Roy shows us, in the words of another novelist from the Indian subcontinent, Salman Rushdie, how “the empire writes back.” Her essays are incisive and at the same time, insightful and provocative, dissecting through the heart of the issue, asking the right questions with precision. In “The Language of Literature,” for instance, Roy asks, “What’s the place of literature?” Or what is its role in our current times which is heavily fraught with religious fundamentalism, the strengthening of the alt Far Right, socioeconomic inequalities and unrest, and even state-funded online disinformation which is prevalent in India and in my country, and possibly everywhere? Come 2020, all these have become layered with the Covid-19 pandemic, i.e. the hoarding of vaccine supply by the Global North, corruption in the midst of pandemic response, racism as evidenced by selective travel bans, as Roy has written in “The Pandemic Is A Portal,” the last essay in the collection. True to her introduction, “Some of the essays in this volume have been written through the eyes of a novelist and the universe of her novels.”

In the larger context of “self against fact” in contemporary nonfiction writing particularly in its subgenres of literary journalism and political essays, Roy shapes and reshapes her position as a witnessing “writer-activist” (which she says people label her) foregrounded by, quoting Nicole Walker in her Creative Nonfiction magazine article The Braided Essay as a Social Justice Action , “new facts, and the facts of your personal story cut into the hard statistics of your paragraph” about political upheavals and ethnoreligious violence in India. I cite Walker because to me, the essays here, a few of them reworked versions of speeches and lectures she gave for the British Library and PEN America, to me, are in the braided form, the “most effective [form] when the political and the personal are trying to explain and understand each other … to [pull] together two disparate ideas … [a] form … of resistance … a form that expands the conversation, presses upon the hard lines of ideology.” In Azadi , Roy critiques across the political spectrum, from the fascist Right (the Hindi ultranationalist Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh) to the “casteist” Left (the Maoist Communist Party of India).

Despite, however, the bleakness of the textual realities of the essays and the lived experiences they portray, Roy, as in her novels The God of Small Things and The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, gives us a glimpse of hope, some sort of light at the end of a pitch-dark tunnel. “What lies ahead?” Roy asks and to which she answers, “Reimagining the world. Only that.”

Sam Dapanas

Nationality: Filipinx

First Language(s): Cebuano Binisaya Second Language(s): English, Tagalog-based Filipino

More about this writer

Our Mission

Our Writers

Submit & Support

Submission Guidelines

Call for Submissions

Wall of Fame

Supported by:

Get involved!

Support tint — support translingual literature.

If you like what Tint Journal does and want us to keep producing literary issues and organizing literary events for ESL writers, support us now with a subscription on Patreon. Thank you for your interest in translingual writing!

Close Subscribe now

Lit. Summaries

- Biographies

The End of Imagination: A Critical Review of Arundhati Roy’s Essays from 2016

- Arundhati Roy

Arundhati Roy is a renowned Indian author and political activist whose essays have been widely read and debated. In this article, we critically review her essays from 2016 and analyze their impact and relevance in today’s world. We examine her views on issues such as nationalism, democracy, and social justice, and assess the strengths and weaknesses of her arguments. Through this analysis, we aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of Roy’s work and its significance in contemporary discourse.

Background Information

Arundhati Roy is an Indian author, political activist, and a recipient of the prestigious Booker Prize for her novel “The God of Small Things.” She is known for her outspoken views on social and political issues, particularly those related to India and its government. In 2016, she published a collection of essays titled “The End of Imagination,” which delves into topics such as the Kashmir conflict, the rise of Hindu nationalism, and the impact of globalization on India’s economy and society. The essays have been widely discussed and debated, with some praising Roy’s boldness and others criticizing her for being too radical. This critical review aims to examine the arguments presented in “The End of Imagination” and evaluate their validity and relevance in today’s world.

Arundhati Roy’s Essays in 2016

Arundhati Roy, the acclaimed Indian author and activist, has been known for her powerful and thought-provoking essays on a range of social and political issues. In 2016, she continued to make waves with her writing, publishing several essays that tackled some of the most pressing issues of our time. From the rise of Hindu nationalism in India to the refugee crisis in Europe, Roy’s essays were a sharp critique of the status quo and a call to action for those who seek a more just and equitable world. In this article, we will take a closer look at some of Roy’s most notable essays from 2016 and explore the themes and ideas that she presented.

The Themes Explored in Roy’s Essays

In her essays, Arundhati Roy explores a wide range of themes, from political corruption and social inequality to environmental degradation and the impact of globalization on local communities. One of the recurring themes in her work is the struggle for justice and human rights, particularly in the face of oppressive regimes and systems of power. Roy is a vocal critic of the Indian government and its policies, and she has been outspoken in her support for marginalized communities and their struggles for autonomy and self-determination. Another important theme in her essays is the need for environmental sustainability and the protection of natural resources. Roy is a passionate advocate for the preservation of India’s forests and rivers, and she has written extensively about the devastating impact of industrialization and urbanization on the country’s ecosystems. Overall, Roy’s essays are a powerful call to action, urging readers to confront the injustices and inequalities that exist in our world and to work towards a more just and sustainable future.

The Writing Style of Arundhati Roy

Arundhati Roy is known for her unique writing style that blends fiction and non-fiction seamlessly. Her essays are often poetic and lyrical, with vivid descriptions that transport the reader to the heart of the issue she is discussing. She is unafraid to use strong language and imagery to convey her message, and her writing is often deeply emotional and passionate. At the same time, she is a master of research and analysis, and her essays are always well-researched and backed up by facts and figures. Overall, Roy’s writing style is both powerful and beautiful, making her essays a joy to read even as they tackle some of the most pressing issues of our time.

The Impact of Roy’s Essays on Indian Society

Arundhati Roy’s essays have had a significant impact on Indian society, particularly in terms of raising awareness about issues such as caste discrimination, environmental degradation, and government corruption. Her writing has been praised for its boldness and honesty, as well as its ability to challenge the status quo and inspire social change. Many readers have been moved by Roy’s passionate advocacy for the marginalized and oppressed, and her willingness to speak truth to power. However, her work has also been criticized by some for being too radical or divisive, and for promoting a negative view of India and its people. Despite these criticisms, it is clear that Roy’s essays have had a profound impact on Indian society, and will continue to shape public discourse and debate for years to come.

The Role of Activism in Roy’s Essays

Arundhati Roy’s essays are known for their strong political and social commentary, and activism plays a crucial role in her writing. Throughout her essays, Roy advocates for marginalized communities and speaks out against injustices such as corporate greed, government corruption, and environmental destruction. She uses her platform to raise awareness and inspire action, encouraging readers to become involved in activism themselves. Roy’s writing is a call to action, urging readers to take a stand and fight for a better world. Her activism is not just a theme in her essays, but a driving force behind her writing.

The Criticism of Roy’s Essays

Despite the acclaim that Arundhati Roy’s essays have received, there has been criticism of her work. Some have accused her of oversimplifying complex issues and presenting a one-sided view of events. Others have argued that her writing is too polemical and lacks nuance. In particular, some critics have taken issue with her portrayal of India as a country plagued by corruption and inequality, arguing that she ignores the progress that has been made in recent years. Despite these criticisms, however, Roy’s essays continue to be widely read and discussed, and her voice remains an important one in contemporary political discourse.

The Reception of Roy’s Essays

The reception of Roy’s essays has been mixed, with some praising her bold and unapologetic critiques of the Indian government and its policies, while others have criticized her for being too radical and divisive. Many have also questioned her credentials as a political commentator, arguing that her background as a novelist does not qualify her to speak on complex political issues. Despite these criticisms, Roy’s essays have sparked important conversations about the state of democracy and human rights in India, and have inspired many to take action and speak out against injustice.

The Influence of Roy’s Essays on Contemporary Indian Literature

Arundhati Roy’s essays have had a significant impact on contemporary Indian literature. Her writing style, which is both poetic and political, has inspired many writers to explore similar themes in their own work. Roy’s essays have also challenged the dominant narratives of Indian society, particularly with regards to issues of caste, gender, and environmental justice. Many writers have been influenced by Roy’s commitment to social justice and her willingness to speak truth to power. In this way, Roy’s essays have helped to shape the direction of contemporary Indian literature, encouraging writers to engage with the pressing issues of our time.

The Significance of Roy’s Essays for the Global Community

Arundhati Roy’s essays have been a significant contribution to the global community, especially in the context of social and political issues. Her writings have been a voice for the marginalized and oppressed, and have brought attention to the injustices and inequalities that exist in our world. Roy’s essays have also been a call to action, urging readers to take a stand and fight for a more just and equitable society. Her work has inspired many to become more engaged in social and political activism, and has helped to create a more informed and aware global community. Overall, Roy’s essays have been a powerful force for change, and will continue to be an important resource for those seeking to create a better world.

The Future of Roy’s Essays in Indian Literature

As Arundhati Roy’s essays continue to spark controversy and debate in Indian literature, it is clear that her work will have a lasting impact on the literary landscape. While some may criticize her for being too political or too radical, others see her as a necessary voice in a society that often silences dissenting opinions. As India continues to grapple with issues of social justice, inequality, and political corruption, Roy’s essays will undoubtedly remain relevant and important. Whether or not her ideas are embraced by the mainstream, her work will continue to inspire and challenge readers for years to come.

The Political Implications of Roy’s Essays

Arundhati Roy’s essays have always been politically charged, and her latest collection, The End of Imagination, is no exception. In fact, the political implications of her essays are perhaps more significant now than ever before. Roy’s writing is a powerful critique of the current political climate in India, and her essays offer a scathing indictment of the ruling party and its policies. She is unafraid to speak truth to power, and her words have the potential to inspire change. However, her essays are not just relevant to India; they have global implications as well. Roy’s writing is a reminder that the fight for justice and equality is ongoing, and that we must remain vigilant in the face of oppression. Her essays are a call to action, urging readers to take a stand against injustice and to fight for a better world.

The Societal Implications of Roy’s Essays

Arundhati Roy’s essays from 2016 have significant societal implications that cannot be ignored. Her critiques of the Indian government’s policies towards Kashmir and the Narmada dam project shed light on the human rights violations and environmental destruction that have been perpetuated in the name of development. Roy’s essays also challenge the dominant narratives of nationalism and patriotism, urging readers to question the legitimacy of the state and its actions. These ideas have the potential to inspire social movements and activism, as well as provoke important conversations about the role of the state in society. However, they also face resistance from those who are invested in maintaining the status quo. The societal implications of Roy’s essays are complex and multifaceted, but they cannot be ignored in the current political climate.

The Cultural Implications of Roy’s Essays

Arundhati Roy’s essays have had a significant impact on the cultural landscape of India. Her critiques of the government’s policies and actions have sparked important conversations about democracy, human rights, and social justice. Roy’s writing has also challenged traditional notions of gender and sexuality, and has given voice to marginalized communities. Her work has been both celebrated and criticized for its political and cultural implications, but there is no denying that it has had a profound effect on the way we think about India and its place in the world.

The Ethical Implications of Roy’s Essays

Arundhati Roy’s essays have always been a source of controversy and debate. While some praise her for her bold and unapologetic stance on issues such as human rights, environmentalism, and social justice, others criticize her for being too radical and divisive. However, beyond the political and ideological debates, there are also ethical implications to consider when reading Roy’s essays.

One of the main ethical concerns is the way Roy portrays her opponents. In many of her essays, she uses strong language and harsh criticism to denounce those who disagree with her views. While it is understandable that she feels passionate about her causes, some argue that her tone can be dismissive and disrespectful towards those who hold different opinions. This raises questions about the ethics of public discourse and the importance of respecting diversity of thought and opinion.

Another ethical issue that arises from Roy’s essays is the way she uses her platform to promote her own agenda. While it is admirable that she uses her voice to raise awareness about important issues, some argue that she can be too self-promoting and self-righteous in her writing. This raises questions about the ethics of activism and the importance of humility and collaboration in social movements.

Overall, while Roy’s essays are thought-provoking and challenging, they also raise important ethical questions about the way we engage in public discourse and activism. As readers, it is important to critically examine not only the content of her essays but also the ethical implications of her writing.

The Historical Implications of Roy’s Essays

Arundhati Roy’s essays have had a significant impact on the historical and political discourse in India. Her writings have challenged the dominant narratives of the Indian state and its policies, particularly in relation to issues of caste, gender, and environmental justice. Roy’s work has also been instrumental in highlighting the struggles of marginalized communities and bringing their voices to the forefront of public discourse. Her critiques of neoliberalism and globalization have been particularly influential in shaping the political consciousness of a generation of activists and intellectuals. Overall, Roy’s essays have played a crucial role in shaping the historical and political landscape of contemporary India.

The Literary Implications of Roy’s Essays

Arundhati Roy’s essays from 2016 are not only politically charged but also have significant literary implications. Roy’s writing style is poetic and evocative, and she often uses metaphors and imagery to convey her message. Her essays are not just political commentary but also works of art that challenge the reader’s imagination. Roy’s use of language is powerful and emotive, and she has a unique ability to capture the essence of a moment or an idea in a few well-chosen words. Her essays are a testament to the power of literature to inspire and provoke change. Roy’s work is a reminder that literature can be a tool for social and political transformation, and that writers have a responsibility to use their craft to speak truth to power.

The Philosophical Implications of Roy’s Essays

Roy’s essays from 2016 have significant philosophical implications that are worth exploring. One of the most prominent themes in her writing is the idea of power and its corrupting influence. She argues that those in positions of power often abuse their authority and exploit the less privileged for their own gain. This raises important questions about the nature of power and its relationship to morality. Is power inherently corrupting, or can it be wielded in a just and ethical manner? Roy’s essays suggest that the answer is not clear-cut and that we must be vigilant in holding those in power accountable for their actions. Another philosophical implication of Roy’s writing is the importance of empathy and compassion. She frequently highlights the suffering of marginalized communities and calls for greater empathy and understanding towards their struggles. This raises questions about the nature of morality and our obligations to others. Should we prioritize the well-being of others over our own self-interest, or is it possible to strike a balance between the two? Roy’s essays suggest that empathy and compassion are essential for creating a more just and equitable society. Overall, Roy’s essays offer important insights into some of the most pressing philosophical questions of our time.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

The Prescient Anger of Arundhati Roy

By Samanth Subramanian

Nine months can make a person, or remake her. In October, 1997, Arundhati Roy won the Booker Prize for her first novel, “ The God of Small Things .” India had just turned fifty, and the country needed symbols to celebrate itself. Roy became one of them. Then, in July of 1998, she published an essay about another such symbol: a series of five nuclear-bomb tests conducted by the government in the sands of Rajasthan. The essay, which eviscerated India’s nuclear policy for placing the lives of millions in danger, wasn’t so much written as breathed out in a stream of fire. Roy’s fall from darling to dissident was swift, and her landing rough. In India, she never attained the heights of adulation again.

Not that she sought them. Through the decades since, Roy has continued to produce incendiary essays, and a new book, “ My Seditious Heart ,” collects them in a volume that spans nearly nine hundred pages. The book opens with her piece from 1998, “The End of Imagination,” but India’s nuclear tests were not Roy’s first infuriation. In fact, in 1994—after she had graduated from architecture school, and around the time that she was acting in indie films, teaching aerobics, and working on her novel—she wrote two livid articles about a Bollywood movie’s unscrupulous depiction of the rape of a real, living woman. That tone has never faltered. Every one of the essays in “My Seditious Heart” was composed in the key of rage.

Roy is often asked why she turned her back on fiction. (Her second novel, “ The Ministry of Utmost Happiness ,” wasn’t published until 2017.) “Another book? Right now?” she once told a journalist. “This talk of nuclear war displays such contempt for music, art, literature and everything else that defines civilization. So what kind of book should I write?” The more interesting question, of course, is why Roy clung to nonfiction, and how she engages within it—the timbre of her reaction to demagoguery, inequality, corporate malfeasance, and the spoliation of the environment. The West’s liberal citizens are beginning to think afresh about how they ought to respond to such provocations: about whether there is virtue in cool balance, or dishonor in uninhibited anger, or utility in mustering a radical Left to counter a hostile Right. They could look to Roy for some answers. She has been ploughing this field for twenty-five years.

In “My Seditious Heart,” Roy rides to battle against a host of troubles. Most frequently, she criticizes India’s fondness for big dams, and its cruelty to the people displaced by them. She lambasts the American imperium and its souped-up capitalism, multinational institutions like the World Bank, and corporate greed. She flays the Hindu supremacists in India , who have sparked pogroms, divided communities, and tightened their hold on power, and she writes with sympathy about Maoists, the militant insurgents in central India who are fighting a state that is plundering the earth of ore and coal. Roy’s preoccupation with these topics has been so absolute that her second novel, when she finally produced it, was stocked with characters personifying her causes. One has a name, Azad Bhartiya, that translates as “Free Indian.” Bhartiya has been fasting for eleven years against assorted evils, and at the site of his protest he lists some of them on a laminated cardboard sign:

I am against the Capitalist Empire, plus against US Capitalism, Indian and American State Terrorism / All Kinds of Nuclear Weapons and Crime, plus against the Bad Education System / Corruption / Violence / Environmental Degradation and All Other Evils. Also I am against Unemployment. I am also fasting for the complete obliteration of the entire Bourgeois class.

If Roy ever begins a hunger strike, one feels that she will place herself behind just such a placard.

When Roy’s essays appeared individually, in magazines or newspapers, they functioned as little jabs of electricity, shocking us into reaction. Collectively, in “My Seditious Heart,” they remind us that many of the flaws in her nonfiction recur and persist. Her instinct to condemn becomes wearisome, and she gives us only the vaguest prescriptions for the systems she wishes would replace market-driven democracy, or dams, or globalization. She is prone to romanticizing the pre-modern, prompting us to wonder if she speaks too glibly for others. (“In their old villages,” she writes of displaced tribes, “they had no money, but they were insured. If the rains failed, they had the forests to turn to. The river to fish in. Their livestock was their fixed deposit.”) In stretches, the text is burdened by rhetorical questions and metaphors. (An essay titled “Democracy: Who is She When She’s at Home?” features three images in two successive sentences to describe how political parties treat Indian democracy: they till its marrow, mine it for electoral advantage, and tunnel under it like “termites excavating a mound.”) And her presentation of data can be self-serving. Repeatedly, she writes that around eight hundred million Indians live on less than twenty rupees (about thirty cents) a day. That statistic, from a 2005 government report, changed with time; by 2011 , when she was still using the figure, the government estimated that nearly two hundred and seventy million people lived on less than thirty rupees a day. Admitting to that reduction would have complicated her arguments, which may explain why she never updated her numbers.