- Memberships

Carroll’s CSR Pyramid explained: Theory, Examples and Criticism

Carroll’s CSR pyramid: this article provides a practical explanation of Carroll’s CSR pyramid . Next to a brief explanantion of this theory, this article also highlights the definition Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), the relevance of Archie Carroll’s Pyramid of CSR, the four main components, various examples and criticism on this strategy approach. Enjoy reading!

Archie Carroll’s CSR Pyramid explained, the basic theory

Carroll’s CSR pyramid is a framework and theory that explains how and why organisations should take social responsibility. The pyramid was developed by Archie B. Carroll and highlights the four most important types of responsibility of organisations.

- Economic responsibility

- Legal responsibility

- Ethical responsibility

- Philanthropic responsibility

The Pyramid of CSR base is profit. This foundation is necessary for a company to meet all laws and regulations, as well as the demands of shareholders. Before a company can and should then take its philanthropic responsibility or discretionary responsibility, it must also meet its ethical responsibilities.

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) as defined by Archie B. Carroll

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has been a popular phrase since the 1950s. The importance of the term and its execution didn’t become clear until much later, however.

The basis of the modern definition of CSR is rooted in the work that led to Archie Carroll’s pyramid. This four-part definition was originally published by Archie B. Carroll in 1979: CSR refers to a business’s behaviour, that it’s economically profitable, complies with the law, is ethical, and is socially supportive.

Profitability and compliance with the law are the most important conditions for corporate social responsibility and when discussing the company’s ethics, and the level to which it supports the society it’s part of with money, time, and talent.

In 1991, he expanded on this definition using a pyramid. The goal of the pyramid was to illustrate the building-block character of the four-part framework. This geometric shape was chosen because it’s both simple and timeless.

The economic responsibility was placed at the pyramid’s foundation, since it’s a fundamental requirement to survive in business.

As with a building’s foundation that keeps the entire structure up, durable profitability helps to support the expectations of society, shareholders, and other stakeholders .

The relevance of Carroll’s pyramid

Almost 30 years after the pyramid was developed, it’s as important as ever. The design is still regularly quoted, changed, discussed, and criticised by business leaders, politicians, scholars, and social pundits.

In order to understand the real relevance of Carroll’s CSR pyramid, we have to go beyond the debate and focus more on the practical application of corporate social responsibility.

The importance of the pyramid will continue to exist because the methods explained in it are understood by all organisations and can be used to reach the top of the pyramid.

What are the four components of Carroll’s CSR pyramid?

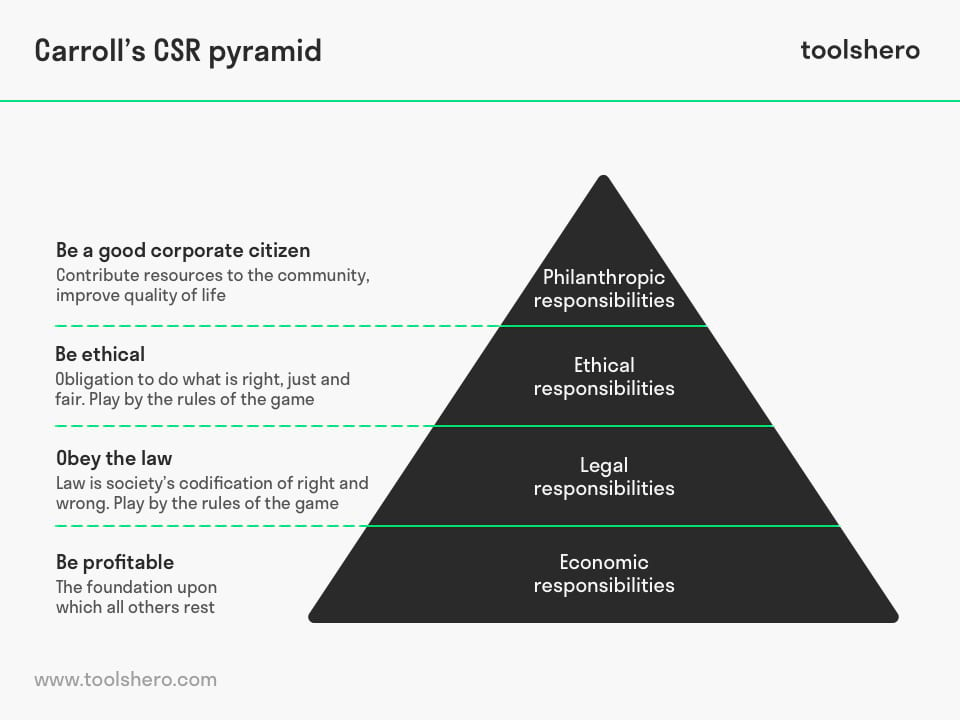

figure 1 – the four components of Archie Carroll’s Pyramid of CSR

Economic responsibility in Carroll’s CSR pyramid

The economic responsibility of companies is about producing goods and services that society needs and to make a profit on them.

Companies have shareholders who expect and demand a reasonable return on their investments , they have employees who want to do their jobs safely and fairly, and have customers that want quality products for fair prices. That’s the foundation of the pyramid upon which all the other layers rest.

Economic responsibility in CSR is:

- The responsibility to be profitable

- The only way for a business to survive and support society in the long term

Legal responsibility in Carroll’s CSR pyramid

The legal responsibility of companies is about complying with the minimum rules that have been set. Organisations are expected to operate and function within those rules. The basic rules consist of laws and regulations that represent society’s views of codified ethics.

They determine how organisations can conduct their business practices in a fair manner, as defined by legislators on national, regional, and local level. Legal responsibility in CSR is:

- Operating in a consistent way in accordance with government requirements and the law

- Complying with different national and local regulations

- Behaving as loyal state and company citizens

- Meeting legal obligations

- Supplying goods and services that meet the minimum legal requirements

Ethical responsibility in Carroll’s CSR pyramid

The ethical responsibility of businesses goes beyond society’s normative expectations – laws and regulations. In addition, society expects organisations to conduct and manage their business in an ethical manner.

Taking ethical responsibility means that organisations embrace activities, standards, and practices that haven’t necessarily been written down, but are still expected.

The difference between legal and ethical expectations can be difficult to determine. Obviously, laws are based on ethical premises, but ethics goes beyond that.

Ethical responsibility in CSR includes:

- Performing in a way that’s consistent with society’s expectations

- Recognising and respecting new or evolving ethical and moral standards that have been adopted by society

- Preventing ethical standards from being infringed upon to achieve objectives

- Being proper business citizens by doing what’s ethically or morally expected

- Acknowledging that business integrity and ethical behaviour go beyond compliance with laws and regulations

Philanthropic responsibility or discretionary responsibility in Carroll’s CSR pyramid

The philanthropic responsibility of businesses includes the voluntary or discretionary activities and practices of businesses.

Philanthropy isn’t a literal responsibility, but nowadays business are expected by society to take part in such activities. The nature and quantity of these activities are voluntary and are guided by companies’ desire to take part in social activities that are generally not expected from organisations in an ethical sense.

Businesses developing philanthropic or discretionary activities give the public the impression that the company wants to give something back to the community.

In order to do so, businesses adopt different types of philanthropy, such as gifts, donations, volunteer work, community development, and all other discretionary contributions to the community or groups of stakeholders that make up that community.

Various examples of Archie Carroll’s CSR pyramid

Successful businesses often have plenty of ways in which they can take responsibility. They don’t always do so, however. Here are a few examples of businesses that either have or have not.

Example of economic responsibility

Companies’ economic responsibilities are aimed at methods that enable the business in the long term , while at the same time meeting the standards for ethics, philanthropy, and legal practices.

Companies that adapt manufacturing processes to be able to use recycled products and lower material costs are examples of economically responsible companies. This benefits society in several ways; increased profitability, reduced ecological footprint.

Example of legal responsibility

The second layer of Carroll’s CSR pyramid is the legal obligation of companies to comply with laws and regulations.

That also includes not looking the other way when grey areas of the law are being ignored or circumvented. This endangers the company. Fines can be steep when these laws aren’t being complied with.

An example is meeting regulations set by the food standards agency. If someone becomes ill due to an organisation’s action, this could result in expensive legal proceedings which might even destroy the company. This would then lead to job losses and financial setbacks for suppliers.

Example of ethical responsibility

The organisational focus on ethics is often about offering fair working conditions for employees, both of the business itself as well as its suppliers. Honest business practices include equal pay for equal work and compensation initiatives.

An example of ethical business practices is the use of products which have fair-trade certification. Ben & Jerry’s, for instance, only uses fair-trade certified ingredients, such sugar, coffee, bananas, and vanilla.

Example of philanthropic / discretionary responsibility

Philanthropic initiatives include donations in the form of time, money, or resources to regional, national, or international charities. The co-founder of Microsoft, Bill Gates , is a good example of that.

Together with his wife Melinda Gates, they founded the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation , to which he has donated billions.

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation focuses on developing education, eradicating malaria, and agricultural development, among other things. In 2014, Bill Gates was the most generous philanthropist in the world, donating 1.5 billion to the Bill and Melinda Foundation.

Carroll’s CSR pyramid criticism

Archie Carroll’s CSR model was the first one to emphasise how important it is that organisations take social responsibility beyond maximising profits. However, he did underline the importance that organisations have to make a profit. This is a strength compared to other CSR theories.

Cultural differences

However, the model also has its limitations. One being that it’s based on American (Western) experiences. Researchers Crane and Maten, for example, claim that the model doesn’t address conflicting obligations, nor how both the national and corporate culture manifest themselves.

They came to this conclusion when applying it to European companies and noticing how different layers of the pyramid had different meanings in different European countries. According to them, that was the result of the highly diverse historical and religious traditions and norms.

Other points of criticism

- In part due to the criticism mentioned above, the model is considered by many to be overly simplistic

- Others claim that the ethical responsibility should be given a more prominent position within the pyramid

- Organisations don’t always do what they say when it comes to CSR

Carroll’s CSR pyramid summary

In short, the four-part definition of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and Carroll’s CSR pyramid offer a conceptual framework for organisations that consists of the economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic or discretionary responsibility.

Businesses’ economic responsibility to make a profit is expected of them by their shareholders. The ethical responsibility of businesses is expected by society.

Now it’s your turn

What do you think? Do you recognise the explanation about Carroll’s CSR pyramid? What other responsibilities do you think businesses have? What role do companies play in solving major or even global issues? Do you have any tips or additional comments?

Share your experience and knowledge in the comments box below.

More information

- Carroll, A. B. , & Näsi, J. (1997). Understanding stakeholder thinking: Themes from a Finnish conference . Business Ethics: A European Review, 6(1), 46-51.

- Carroll, A. B. (1999). Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of a definitional construct . Business & society, 38(3), 268-295.

- Carroll, A. B. (2016). Carroll’s pyramid of CSR: taking another look . International journal of corporate social responsibility, 1(1), 3.

- Jamali, D., & Carroll, A. B. (2017). Capturing advances in CSR: Developed versus developing country perspectives . Business Ethics: A European Review, 26(4), 321-325.

- Pinkston, T. S., & Carroll, A. B. (1996). A retrospective examination of CSR orientations: have they changed? . Journal of Business Ethics, 15(2), 199-206.

How to cite this article: Janse, B. (2020). Carroll’s CSR Pyramid explained: Theory, Examples and Criticism . Retrieved [insert date] from Toolshero: https://www.toolshero.com/strategy/carroll-csr-pyramid/

Published on: 07/22/2020 | Last update: 02/24/2023

Add a link to this page on your website: <a href=”https://www.toolshero.com/strategy/carroll-csr-pyramid/”>Toolshero: Carroll’s CSR Pyramid explained: Theory, Examples and Criticism</a>

Did you find this article interesting?

Your rating is more than welcome or share this article via Social media!

Average rating 4.1 / 5. Vote count: 17

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Ben Janse is a young professional working at ToolsHero as Content Manager. He is also an International Business student at Rotterdam Business School where he focusses on analyzing and developing management models. Thanks to his theoretical and practical knowledge, he knows how to distinguish main- and side issues and to make the essence of each article clearly visible.

Related ARTICLES

PMESII-PT Analysis, an army Theory explained

SOAR Analysis: the theory plus example and template

Corporate Governance: the definition and basics

Eight Dimensions of Quality by David Garvin

Strategic Business Unit (SBU): Definition and Theory

Golden Circle by Simon Sinek

Also interesting.

Service Profit Chain Model and Steps explained

Theory of Constraints by Eliyahu Goldratt

Flywheel Concept by Jim Collins

Leave a reply cancel reply.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

BOOST YOUR SKILLS

Toolshero supports people worldwide ( 10+ million visitors from 100+ countries ) to empower themselves through an easily accessible and high-quality learning platform for personal and professional development.

By making access to scientific knowledge simple and affordable, self-development becomes attainable for everyone, including you! Join our learning platform and boost your skills with Toolshero.

POPULAR TOPICS

- Change Management

- Marketing Theories

- Problem Solving Theories

- Psychology Theories

ABOUT TOOLSHERO

- Free Toolshero e-book

- Memberships & Pricing

How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 12 min read

Carroll's Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility

Looking beyond your core responsibilities.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is a "must have" for most organizations these days. Not only because of the benefits it can bring to the environment and local communities, but also because of the benefits it can bring to the organization – increased profits and valuation, greater employee engagement and retention, and lower risk. [1] But, when you come to plan your CSR strategy, where should you start?

Planning your CSR strategy can often be quite tricky work, involving gathering metrics from across the organization, analyzing supply chains, and gaining input from a whole host of internal and external stakeholders. Not to mention choosing between conflicting priorities and investment opportunities.

In this article, we'll look at a model, known as Carroll's Pyramid of CSR, that can help to simplify this process, and explore how to design and implement an effective CSR strategy in your organization.

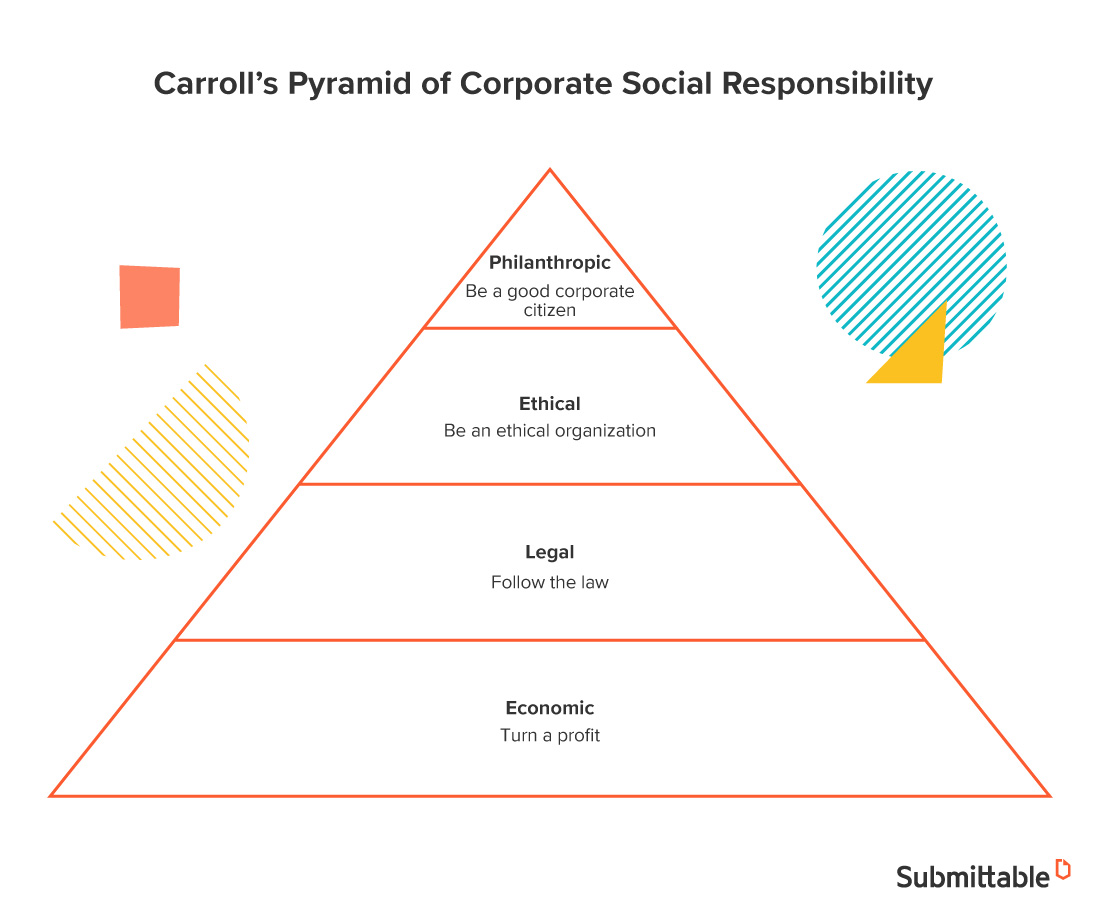

What Is Carroll's Pyramid of CSR?

To survive, every business must at least make a profit and meet its legal responsibilities. But what it does with those profits, and what higher values it demonstrates to its employees, customers, community and market, will vary enormously.

According to Professor Archie Carroll, CSR "... can only become a reality if managers become moral instead of amoral or immoral."

It's not enough to simply focus on one area of the business. CSR must encompass all organizational activities, processes and goals. To help organizations to clarify their responsibilities, Carroll designed a model known as the Pyramid of CSR (see figure 1, below), which demonstrates on organization's hierarchy of responsibilities. He asserted that only by carrying out all of these responsibilities together would effective CSR be achieved. [2]

Figure 1. Carroll's Pyramid of CSR

Carroll's Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility, reproduced with permission from Carroll, A.B. (1991). "The Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility: Toward the Moral Management of Organizational Stakeholders." [2]

How to Use Carroll's Pyramid of CSR

Carroll's Pyramid breaks down an organization's responsibilities into four key areas. The organization must be accountable for all of these in order to ensure successful CSR.

Let's take a look at each of these four key areas in more detail and explain how you can make them work for you.

Economic Responsibilities

Forming the base of the pyramid are your economic responsibilities. Simply put, this is about ensuring that your organization remains profitable and financially transparent. Responsibilities in this slice of the pyramid should include:

- Keeping your costs to a minimum.

- Maximizing income.

- Investing in developing and growing the business in the long term.

- Ensuring financial risks are managed correctly.

- Providing a return to your owners and/or shareholders.

Being economically responsible enables you to create and sustain jobs in the community, and contribute useful, non-harmful products and services to society.

Everyone in an organization, from the top down, can help to deliver this responsibility by ensuring that finances are managed in an ethical and fair way. This means asking yourself – are you profitable and legal? Are you profitable and legal, but also acting ethically? For example, a company may keep costs down by using low-cost supply chains, but this may mean using suppliers who utilize low-cost, cheap labor and poor working practices.

To excel in this area, think about the pinnacle of the pyramid! Are you also encouraging, supporting or carrying out far-reaching beneficial programs, beyond the basic legislative requirements?

For instance, Hewlett-Packard, which is currently ranked first on the KnowtheChain ICT benchmark for forced labor, and sector leader on the Dow Jones Sustainability World Index, has invested $1.9 billion researching and developing next-generation technologies. These have included things like new silicon designs, photonics (technology and science of light generation, which is often used in consumer electronics), and Memory-Driven Computing, all of which will massively improve computer processing but also reduce energy usage. [3]

Legal Responsibilities

This is also straightforward and a minimum requirement for all businesses: to obey the law.

Responsibilities covered by this area of the pyramid entail:

- Being truthful and transparent about the safety and security of the products or services you sell.

- Keeping your employees and customers safe.

- Ensuring that you meet environmental, health and safety requirements.

- Paying your taxes.

At the very least, it's about protecting your organization from prosecution or penalty, which would impact its profits and reputation, and could even lead to it being shut down. The best way to meet these responsibilities is to report on your performance and activities in an open and transparent way.

One of the best examples to demonstrate responsibility in this area is environmental regulation. Organizations are often required by law to meet certain environmental standards relating to pollution and emissions. But many go over and above these legal requirements.

For instance, Johnson & Johnson has set an organizational goal of "net-zero carbon" across its value chain by 2045. The company already has a number of environmental projects underway to support this goal, including acquiring Colbeck Corner's wind farm in Texas which supplies 60 percent of the company's renewable energy. It is also expanding its geothermal energy operations and solar panel infrastructure, and has continued to invest in Leadership and Energy & Environmental Design (LEED) certification across several of its office sites. [4]

Ethical Responsibilities

This extends your obligations to doing what is right and fair, even if it's not required by law. To attend to this responsibility, you'll need the "moral" outlook that Carroll refers to.

An example would be avoiding structuring your company so that it pays little or no taxes, even if that would be allowed by the letter of the law. Or, on a smaller scale, supporting flexible working for your team members so that they can juggle caregiving responsibilities with their jobs.

Some ethical issues are harder to tease out . For example, you could be making your product safely and efficiently, selling it at a fair price, and treating your people well. But what if that product is a food item that has a lot of sugar in it – should you change the recipe?

Coca-Cola, for instance, has invested significantly in reducing the sugar content of its drinks, and removed nearly 125,000 tons of added sugar through recipe changes in 2020. This has enabled it to reduce sugar content by up to 30 percent in some of its leading brands, including Coca-Cola, Fanta, Sprite, and Fuze Tea. [5]

However, while Coca-Cola has done well in this area, it has still come under heavy criticism for the amount of plastic waste it's responsible for. The company is working hard to address this issue, too, announcing in 2021 that it's collaborating with tech partners to produce bottles that are made from 100 percent renewable plant-based materials. [6]

Philanthropic Responsibilities

This is the highest level of responsibility and goes beyond any legal or regulatory expectations. It's about being a "good corporate citizen," actively improving the world around you.

Examples of philanthropic CSR would be:

- Enabling team members to take part in volunteering programs during work time.

- Sponsoring community initiatives.

- Offering mentoring expertise to nonprofits.

- Entering into community or charitable partnerships.

- Donating to charity, and offering employee donation-match schemes.

- Tackling wider global issues, such as poverty, climate change, racism, or gender inequality.

Some organizations even establish their own philanthropic or charitable foundations, such as the Ford Foundation , the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation , and the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation .

Biopharmaceutical company Gilead Sciences is consistently one of the top corporate givers in the world, donating $388 million to good causes in 2020, equating to 2.9 percent of its pre-tax profit. [7] And it announced a further investment of $200 million in its charitable arm, the Gilead Foundation, in 2021, with the money going toward supporting health justice, community giving, and its employee donation-match scheme. [8]

The Benefits of Carroll's Pyramid of CSR

Carroll's pyramid builds responsibility upon responsibility, and is intended to be applied as a whole. This means that succeeding at one or two areas is not enough.

Clearly, meeting your economic responsibilities while overlooking your legal responsibilities, or vice versa, will mean that your organization runs into difficulties sooner or later. This may mean that ethical and philanthropic responsibilities are seen as optional. But fulfilling them can provide a number of benefits, too, such as:

- Building and Improving Your Reputation. Demonstrating that you're an ethical and philanthropic organization can imply that you're committed to operating in a responsible way, which can help to build trust in your product, too. It can also give you a competitive edge, and enable you to attract consumers who are also ethically minded.

- Increasing sustainability. Being "green" can have direct financial benefits. Cutting your carbon emissions and using energy from renewable sources can save costs, as can improving production and supply-chain efficiency, and reducing your carbon taxes. Investing in your "triple bottom line" is a good way to deliver these benefits and set organizational goals that are built around profit, people and the planet.

- Attracting and retaining talent. Embracing CSR can position you as an "employer of choice." People will aspire to work for you and, once they join, they'll feel proud and purposeful , and will want to stay. They'll also be able to enjoy interesting opportunities beyond their formal roles (for example, through volunteering initiatives or company charity drives) and talk positively about you to family and friends. That means you'll always have the pick of the best candidates for vacancies!

The Challenges of Implementing Carroll's CSR Pyramid

Simultaneously addressing all four responsibilities covered by Carroll's Pyramid is the biggest challenge. This is because ethical principles can sometimes conflict with your organization's economic priorities. For example, will a promising new contract, an investment opportunity, or utilizing a low-cost supplier conflict with your ethical stance ?

Investing in CSR can also take up resources, and even shift your focus away from your core activities. A major corporation may be able to allocate a budget, and even a dedicated team, to its CSR activities. But a smaller organization won't have that luxury.

Worse still, if you cynically promote your CSR credentials but don't deliver, or if you're found to be neglecting the basics, you'll be accused of "greenwashing." This means hiding a dirty reality under a clean, but shallow, facade. And, if you're found guilty of it, your reputation will be wrecked. For example, your certified organic cotton fabric won't matter one bit if your employees are making clothes from it in sweatshop conditions. Similarly, an employee volunteer program can't be a substitute for decent wages or working conditions.

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is a key part of most organizations' strategies and operations nowadays. But it's often not enough to just focus on one area of the business to achieve successful CSR. It must encompass all organizational activity, processes and goals.

Carroll's Pyramid of CSR provides a framework that organizations can use to clarify and improve their responsibilities across four key areas:

- Philanthropic.

Carroll argues that successful CSR can only be achieved by ensuring organizational responsibility in all four of these areas. Furthermore, doing so can bring with it a number of benefits, such as building and improving brand reputation, increasing sustainability, cutting costs, and increasing your ability to attract and retain talent.

[1] Albuquerque, R., Koskinen, Y., and Zhang, C. (2019). 'Corporate Social Responsibility and Firm Risk: Theory and Empirical Evidence,' Management Science , 65-10, 4451-4469. Available here .

[2] Carroll, A.B. (1991). 'The Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility: Toward the Moral Management of Organizational Stakeholders,' Business Horizons , vol. 34, issue 4, July-August 1991, 39-48, Elsevier. Available here .

[3] Hewlett-Packard Enterprise Co. (2020). 2020 Living Progress Repor t [online]. Available here .

[4] Johnson & Johnson Services Inc. (2021). Global Environmental Sustainability [online]. Available here .

[5] The Coca-Cola Company. (2021). Driving Choice & Reducing Sugar [online]. Available here .

[6] The Coca-Cola Company. (2021). Coca-Cola Collaborates With Tech Partners to Create Bottle Prototype Made from 100% Plant-Based Sources [online]. Available here .

[7] Digital Information World. (2020). The Most Generous Companies and Individuals [online]. Available here.

[8] Gilead Sciences, Inc. (2021). Gilead Sciences Endows its Foundation With More Than $200m to Support Health Justice, Community Giving and Employee Match Program [online]. Available here .

You've accessed 1 of your 2 free resources.

Get unlimited access

Discover more content

The losada ratio.

Balancing Positive and Negative Interactions

The Burke-Litwin Change Model

Unraveling the Dynamics of Organizational Change

Add comment

Comments (0)

Be the first to comment!

Team Management

Learn the key aspects of managing a team, from building and developing your team, to working with different types of teams, and troubleshooting common problems.

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Most Popular

Newest Releases

SWOT Analysis

SMART Goals

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

How to stop procrastinating.

Overcoming the Habit of Delaying Important Tasks

What Is Time Management?

Working Smarter to Enhance Productivity

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

Understanding creativity.

Tools and Techniques for Creative Thinking

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

- Submissions & Reviews

- Publishing & Journals

- Scholarships

- News & Updates

- Resources Home

- Submittable 101

- Bias & Inclusivity Resources

- Customer Stories

- Get our newsletter

- Request a Demo

Understanding & Applying Carroll’s CSR Pyramid

Pyramids have gotten a bad rap in the business world—especially when the word “scheme” is involved.

But Archie Carroll’s Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) might just change your mind about pyramids in the context of corporations.

Because CSR can be complex, messy work that involves legions of internal and external stakeholders often relying heavily on qualitative metrics, frameworks like Carroll’s Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility help to simplify a rather nuanced field.

Now that CSR has firmly moved into the C-suite and today’s consumers expect companies to be good corporate citizens, the stakes are higher than ever. Organizational survival is on the line and profits are no longer the singular metric.

Recent research in the journal Management Science found that companies practicing CSR demonstrated higher profit margins, increased valuation, and lower risk . Researchers even discovered that CSR has the tendency to boost product differentiation (meaning consumers leaned towards companies with a solid CSR reputation) as well as deliver a more stable return on assets even amidst economic fluctuations.

Such data confirm Archie Carroll’s framing of how CSR works for modern companies.

It’s multi-faceted.

From the economic to the philanthropic, organizations are expected to demonstrate just how socially responsible they are at all levels. Let’s tackle precisely what those levels are and how they play out for contemporary organizations.

What is Carroll’s Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility?

Ask Danielle Holly , CEO of Common Impact , whether frameworks matter in CSR.

As a leader in the field, she’ll likely tell you that they matter a great deal. She’ll probably even show you the measurement framework her team developed to evaluate the impact of skills-based volunteer programs.

While CSR activities can range from outright philanthropic giving and skilled volunteerism to in-kind donations and issue area advocacy, those activities still need to be framed at the outset and measured throughout the CSR campaign.

That’s why frameworks like Carroll’s pyramid are supremely helpful.

As Holly notes, “The best CSR programs take into account a company’s overall strategy, its core competencies and employee talents, and the social impact area that it’s best positioned to address.”

In other words, great CSR campaigns vertically integrated through all levels of an organization’s work—internal and external.

To craft a CSR foundation that will resonate with employees and community stakeholders, Holly says that C-suite and mid-level business leaders must be focused on HR, employee engagement and philanthropy.. It’s a package deal.

Carroll’s Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility helps companies think about CSR holistically. If one level is missing or under-resourced, the Great Pyramid of CSR never gets built.

Here’s how organizational leaders can focus on each level while addressing all the layers of CSR.

Organizations should engage on all four levels of Carroll’s pyramid of corporate social responsibility

Southwest Airlines’ triple bottom line (Performance, People, and Planet) approach.

H-E-B grocers’ disaster relief efforts during and after Hurricane Harvey.

Patagonia’s giving its entire $10 million tax cut in 2019 to help mitigate climate change.

Workers at the H-E-B Mobile Kitchen prepare hot meals in Rockport on August 29 for people impacted by Hurricane Harvey.

Photograph by R.G. Ratcliffe

If you’re looking for examples of companies with vertically integrated CSR that are making a big impact, Hannah Nokes has you covered. As the Co-founder of Magnify Impact , she guides companies through a process to “help them determine the strongest foundation for their CSR program.”

For Nokes, it’s pretty simple. Leaders of organizations need to carefully consider what kind of social impact they want to make (“purpose”). That self-reflection needs to align with their organizational capacities (“superpowers”). The end result will be social outcomes (“impact”).

Another very useful framework for CSR.

The companies mentioned above are examples of organizations that have thought and planned long and hard with regard to their purpose and superpowers. Armed with the approach that best suited their brand, they executed up and down Carroll’s Pyramid of CSR.

Here’s a bit more on each level of that pyramid with some helpful business examples.

Get the right tools to support your work

Submittable can help you launch, manage, and measure your CSR program.

Economic responsibilities

At the most basic level, organizations need to create profit through growth. Without succeeding here, there’s no business to do any CSR work.

If a company has any interest in supporting society over the long term, it must meet these core economic responsibilities to its shareholders and stakeholders.

For example, companies that change their approach to packaging materials with a move towards more eco-friendly packaging that is lower in cost than traditional materials would be fulfilling its economic obligation while also meeting environmental obligations.

Legal responsibilities

Organizations must comply with laws and regulations.

These rules are set by governments as part of the social contract. It’s that simple.

It’s important to remember that governments create the markets in which companies exist. Through taxes, fines, and legal interventions of all sorts, citizens empower their leaders to govern the context in which companies conduct their business.

The easy example here is the regulation of our environment.

We have legal frameworks to defend basic human rights to clean air and water because we need those things to survive. Organizations can create and sell their products and services in ways that affect the environment—but only to a point as designated by the government.

When those negative business consequences become too much, companies could face legal proceedings and other levies that set them back financially and threaten their existence. It’s a delicate balance.

Ethical responsibilities

This level of Carroll’s pyramid is all about societal expectations.

Admittedly, those can be opaque. In other words, from company to company, your mileage may vary.

It’s up to management to make those moral decisions that will impact the business, consumers, employees, and the environment. This is where the idea of reputation looms large. Word of mouth and consumer perception has a huge impact on a company’s bottom line.

This is by far the hardest metric that business leaders have to track and manage. It’s also one of the most important.

For example, when employees speak out against internal company practices , companies are often well within their economic and legal “rights” to fire that employee. But should they?

In moments like these, organizational leaders are making difficult cost-benefit calculations. They’re weighing external perception against potential damage that could be inflicted on the company’s economic reality if they choose a different path.

Ethical considerations are rarely easy and they cut to the core of an organization’s values.

Philanthropic responsibilities

These days, businesses are expected to give back.

Generous contributions from companies back to the communities that support them are the baseline nowadays. Modern consumers are hip to the idea that organizations are interconnected with the people and neighborhoods where they do business.

Put succinctly by Senator Elizabeth Warren, everyday citizens just expect well-heeled companies to pay their fair share . Whether it’s corporate taxes or oversized checks handed to deserving students onstage, people have an innate sense that companies should pony up.

One of the most shining examples of corporate philanthropy is Bill Gates. The billionaire who is now getting credit for being ahead of the curve on the threat posed by global pandemics has built a juggernaut philanthropic operation in the form of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation .

From education reform to seeding advancements in agricultural technology, his billions have gone a long way towards key CSR goals.

Integrating the pyramid of corporate social responsibility into your CSR management platform

Just like all pyramids, even Archie Carroll’s has its dull edges.

Some researchers have noted that Carroll’s Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility fails to tackle conflicting obligations that companies often face and the ethical contours of those decisions. Critics have also noted that culture plays a huge role in organizational decision-making and that Carroll’s model fails to meaningfully take this into account.

This might limit how the framework can be applied across cultural contexts. And what happens when companies don’t do what they promise when it comes to CSR? Even the best theoretical models have a hard time accounting for deception.

While it’s important to note the weaknesses of the model, organizations can still benefit from integrating Carroll’s Pyramid of CSR into their broader social impact strategy. One helpful step in that direction would be managing all CSR work from all-in-one CSR software . This allows companies to measure KPIs at various levels of the pyramid and track progress towards overarching CSR goals.

With all of your CSR work being coordinated in one place, corporate managers of CSR can embrace the holistic approach to achieving social change, and start both growing and giving back.

Paul Perry is a writer and former educator with significant experience in nonprofit management. He has a soft spot for grant-seekers striving to make the world a better, more just place.

Review together. From anywhere.

Try the trusted submission management platform to collect and review anything, with anyone, from anywhere.

Watch a demo

About Submittable

Submittable powers you with tools to launch, manage, measure and grow your social impact programs, locally and globally. From grants and scholarships to awards and CSR programs, we partner with you so you can start making a difference, fast. The start-to-finish platform makes your workflow smarter and more efficient, leading to better decisions and bigger impact. Easily report on success, and learn for the future—Submittable is flexible and powerful enough to grow alongside your programs.

Submittable is used by more than 11 thousand organizations, from major foundations and corporations to governments, higher education, and more, and has accepted nearly 20 million applications to date.

HOW IT WORKS

4 Carroll’s Pyramid of CSR

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) in its modern formulation has been an important and progressing topic since the 1950s. To be sure, evidences of businesses seeking to improve society, the community, or particular stakeholder groups may be traced back hundreds of years (Carroll et al. 2012 ). In this discussion, however, the emphasis will be placed on concepts and practices that have characterized the post-World War II era. Much of the literature addressing CSR and what it means began in the United States; however, evidences of its applications, often under different names, traditions, and rationales, has been appearing around the world. Today, Europe, Asia, Australia, Africa, South America, and many developing countries are increasingly embracing the idea in one form or another. Clearly, CSR is a concept that has endured and continues to grow in importance and impact.

To be fair, it must be acknowledged that some writers early on have been critical of the CSR concept. In an important Harvard Business Review article in 1958, for example, Theodore Levitt spoke of “The Dangers of Social Responsibility.” His position was best summarized when he stated that business has only two responsibilities – (1) to engage in face-to-face civility such as honesty and good faith and (2) to seek material gain. Levitt argued that long-run profit maximization is the one dominant objective of business, in practice as well as theory (Levitt 1958 , p. 49). The most well-known adversary of social responsibility, however, is economist Milton Friedman who argued that social issues are not the concern of business people and that these problems should be resolved by the unfettered workings of the free market system (Friedman 1962 ).

Introduction

The modern era of CSR, or social responsibility as it was often called, is most appropriately marked by the publication by Howard R. Bowen of his landmark book Social Responsibilities of the Businessman in 1953. Bowen’s work proceeded from the belief that the several hundred largest businesses in the United States were vital centers of power and decision making and that the actions of these firms touched the lives of citizens in many ways. The key question that Bowen asked that continues to be asked today was “what responsibilities to society may businessmen reasonably be expected to assume?” (Bowen 1953 , p. xi) As the title of Bowen’s book suggests, this was a period during which business women did not exist, or were minimal in number, and thus they were not acknowledged in formal writings. Things have changed significantly since then. Today there are countless business women and many of them are actively involved in CSR.

Much of the early emphasis on developing the CSR concept began in scholarly or academic circles. From a scholarly perspective, most of the early definitions of CSR and initial conceptual work about what it means in theory and in practice was begun in the 1960s by such writers as Keith Davis, Joseph McGuire, Adolph Berle, William Frederick, and Clarence Walton (Carroll 1999 ). Its’ evolving refinements and applications came later, especially after the important social movements of the 1960s, particularly the civil rights movement, consumer movement, environmental movement and women’s movements.

Dozens of definitions of corporate social responsibility have arisen since then. In one study published in 2006, Dahlsrud identified and analyzed 37 different definitions of CSR and his study did not capture all of them (Dahlsrud 2006 ).

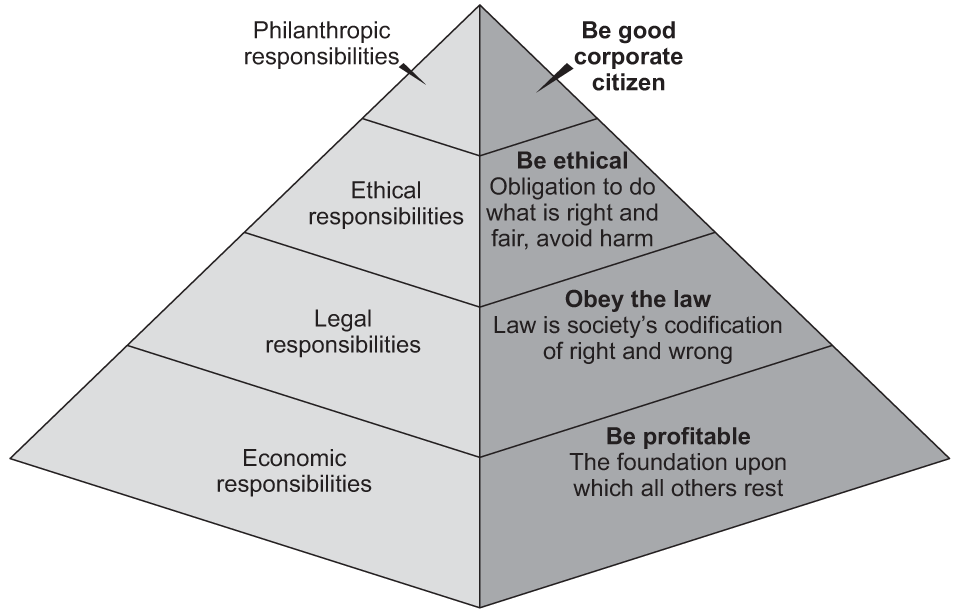

In this article, however, the goal is to revisit one of the more popular constructs of CSR that has been used in the literature and practice for several decades. Based on his four-part framework or definition of corporate social responsibility, Carroll created a graphic depiction of CSR in the form of a pyramid. CSR expert Dr. Wayne Visser has said that “Carroll’s CSR Pyramid is probably the most well-known model of CSR…” (Visser 2006 ). If one goes online to Google Images and searches for “Carroll’s Pyramid of CSR,” well over 100 variations and reproductions of the pyramidal model are presented there ( Google Images ) and over 5200 citations of the original article are indicated there ( Google Scholar ).

The purpose of the current commentary is to summarize the Pyramid of CSR, elaborate on it, and to discuss some aspects of the model that were not clarified when it was initially published in 1991. Twenty five years have passed since the initial publication of the CSR pyramid, but in early 2016 it still ranks as one of the most frequently downloaded articles during the previous 90 days in the journal in which it was published – ( Elsevier Journals ), Business Horizons (Friedman 1962 ) – sponsored by the Kelley School of Business at Indiana University. Carroll’s four categories or domains of CSR, upon which the pyramid was established, have been utilized by a number of different theorists (Swanson 1995 ; Wartick and Cochran 1985 ; Wood 1991 , and others) and empirical researchers (Aupperle 1984 ; Aupperle et al. 1985 ; Burton and Hegarty 1999 ; Clarkson 1995 ; Smith et al. 2001 , and many others). According to Wood and Jones, Carroll’s four domains have “enjoyed wide popularity among SIM (Social Issues in Management) scholars (Wood and Jones 1996 ). Lee has said that the article in which the four part model of CSR was published has become “one of the most widely cited articles in the field of business and society” (Lee 2008 ). Thus, it is easy to see why a re-visitation of the pyramid based on the four category definition might make some sense and be useful.

Many of the early definitions of CSR were rather general. For example, in the 1960s it was defined as “seriously considering the impact of the company’s actions on society.” Another early definition of CSR read as follows: “Social responsibility is the obligation of decision makers to take actions which protect and improve the welfare of society along with their own interests” (Davis 1975 ). In general, CSR has typically been understood as policies and practices that business people employ to be sure that society, or stakeholders, other than business owners, are considered and protected in their strategies and operations. Some definitions of CSR have argued that an action must be purely voluntary to be considered socially responsible; others have argued that it embraces legal compliance as well; still others have argued that ethics is a part of CSR; virtually all definitions incorporate business giving or corporate philanthropy as a part of CSR and many observers equate CSR with philanthropy only and do not factor in these other categories of responsibility.

The ensuing discussion explains briefly each of the four categories that comprise Carroll’s four-part definitional framework upon which the pyramidal model is constructed.

The four-part definitional framework for CSR

Carroll’s four part definition of CSR was originally stated as follows: “Corporate social responsibility encompasses the economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary (philanthropic) expectations that society has of organizations at a given point in time” (Carroll 1979 , 1991 ). This set of four responsibilities creates a foundation or infrastructure that helps to delineate in some detail and to frame or characterize the nature of businesses’ responsibilities to the society of which it is a part. In the first research study using the four categories it was found that the construct’s content validity and the instrument assessing it were valid (Aupperle et al. 1985 ). The study found that experts were capable of distinguishing among the four components. Further, the factor analysis conducted concluded that there are four empirically interrelated, but conceptually independent components of corporate social responsibility. This study also found that the relative values or weights of each of the components as implicitly depicted by Carroll approximated the relative degree of importance the 241 executives surveyed placed on the four components—economic = 3.5; legal = 2.54; ethical = 2.22; and discretionary/philanthropic = 1.30. Later research supported that Aupperle’s instrument measuring CSR using Carroll’s four categories (Aupperle 1984 ) was valid and useful (Edmondson and Carroll 1999 ; Pinkston and Carroll 1996 and others). In short, the distinctiveness and usefulness in research of the four categories have been established through a number of empirical research projects. A brief review of each of the four categories of CSR follows.

Economic responsibilities

As a fundamental condition or requirement of existence, businesses have an economic responsibility to the society that permitted them to be created and sustained. At first, it may seem unusual to think about an economic expectation as a social responsibility, but this is what it is because society expects, indeed requires, business organizations to be able to sustain themselves and the only way this is possible is by being profitable and able to incentivize owners or shareholders to invest and have enough resources to continue in operation. In its origins, society views business organizations as institutions that will produce and sell the goods and services it needs and desires. As an inducement, society allows businesses to take profits. Businesses create profits when they add value, and in doing this they benefit all the stakeholders of the business.

Profits are necessary both to reward investor/owners and also for business growth when profits are reinvested back into the business. CEOs, managers, and entrepreneurs will attest to the vital foundational importance of profitability and return on investment as motivators for business success. Virtually all economic systems of the world recognize the vital importance to the societies of businesses making profits. While thinking about its’ economic responsibilities, businesses employ many business concepts that are directed towards financial effectiveness – attention to revenues, cost-effectiveness, investments, marketing, strategies, operations, and a host of professional concepts focused on augmenting the long-term financial success of the organization. In today’s hypercompetitive global business environment, economic performance and sustainability have become urgent topics. Those firms that are not successful in their economic or financial sphere go out of business and any other responsibilities that may be incumbent upon them become moot considerations. Therefore, the economic responsibility is a baseline requirement that must be met in a competitive business world.

Legal responsibilities

Society has not only sanctioned businesses as economic entities, but it has also established the minimal ground rules under which businesses are expected to operate and function. These ground rules include laws and regulations and in effect reflect society’s view of “codified ethics” in that they articulate fundamental notions of fair business practices as established by lawmakers at federal, state and local levels. Businesses are expected and required to comply with these laws and regulations as a condition of operating. It is not an accident that compliance officers now occupy an important and high level position in company organization charts. While meeting these legal responsibilities, important expectations of business include their

- Performing in a manner consistent with expectations of government and law

- Complying with various federal, state, and local regulations

- Conducting themselves as law-abiding corporate citizens

- Fulfilling all their legal obligations to societal stakeholders

- Providing goods and services that at least meet minimal legal requirements

Ethical responsibilities

The normative expectations of most societies hold that laws are essential but not sufficient. In addition to what is required by laws and regulations, society expects businesses to operate and conduct their affairs in an ethical fashion. Taking on ethical responsibilities implies that organizations will embrace those activities, norms, standards and practices that even though they are not codified into law, are expected nonetheless. Part of the ethical expectation is that businesses will be responsive to the “spirit” of the law, not just the letter of the law. Another aspect of the ethical expectation is that businesses will conduct their affairs in a fair and objective fashion even in those cases when laws do not provide guidance or dictate courses of action. Thus, ethical responsibilities embrace those activities, standards, policies, and practices that are expected or prohibited by society even though they are not codified into law. The goal of these expectations is that businesses will be responsible for and responsive to the full range of norms, standards, values, principles, and expectations that reflect and honor what consumers, employees, owners and the community regard as consistent with respect to the protection of stakeholders’ moral rights. The distinction between legal and ethical expectations can often be tricky. Legal expectations certainly are based on ethical premises. But, ethical expectations carry these further. In essence, then, both contain a strong ethical dimension or character and the difference hinges upon the mandate society has given business through legal codification.

While meeting these ethical responsibilities, important expectations of business include their

- Performing in a manner consistent with expectations of societal mores and ethical norms

- Recognizing and respecting new or evolving ethical/moral norms adopted by society

- Preventing ethical norms from being compromised in order to achieve business goals

- Being good corporate citizens by doing what is expected morally or ethically

- Recognizing that business integrity and ethical behavior go beyond mere compliance with laws and regulations (Carroll 1991 )

As an overlay to all that has been said about ethical responsibilities, it also should be clearly stated that in addition to society’s expectations regarding ethical performance, there are also the great, universal principles of moral philosophy such as rights, justice, and utilitarianism that also should inform and guide company decisions and practices.

Philanthropic responsibilities

Corporate philanthropy includes all forms of business giving. Corporate philanthropy embraces business’s voluntary or discretionary activities. Philanthropy or business giving may not be a responsibility in a literal sense, but it is normally expected by businesses today and is a part of the everyday expectations of the public. Certainly, the quantity and nature of these activities are voluntary or discretionary. They are guided by business’s desire to participate in social activities that are not mandated, not required by law, and not generally expected of business in an ethical sense. Having said that, some businesses do give partially out of an ethical motivation. That is, they want to do what is right for society. The public does have a sense that businesses will “give back,” and this constitutes the “expectation” aspect of the responsibility. When one examines the social contract between business and society today, it typically is found that the citizenry expects businesses to be good corporate citizens just as individuals are. To fulfill its perceived philanthropic responsibilities, companies engage in a variety of giving forms – gifts of monetary resources, product and service donations, volunteerism by employees and management, community development and any other discretionary contribution to the community or stakeholder groups that make up the community.

Although there is sometimes an altruistic motivation for business giving, most companies engage in philanthropy as a practical way to demonstrate their good citizenship. This is done to enhance or augment the company’s reputation and not necessarily for noble or self-sacrificing reasons. The primary difference between the ethical and philanthropic categories in the four part model is that business giving is not necessarily expected in a moral or ethical sense. Society expects such gifts, but it does not label companies as “unethical” based on their giving patterns or whether the companies are giving at the desired level. As a consequence, the philanthropic responsibility is more discretionary or voluntary on business’s part. Hence, this category is often thought of as good “corporate citizenship.” Having said all this, philanthropy historically has been one of the most important elements of CSR definitions and this continues today.

In summary, the four part CSR definition forms a conceptual framework that includes the economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic or discretionary expectations that society places on businesses at a given point in time. And, in terms of understanding each type of responsibility, it could be said that the economic responsibility is “required” of business by society; the legal responsibility also is “required” of business by society; the ethical responsibility is “expected” of business by society; and the philanthropic responsibility is “expected/desired” of business by society (Carroll 1979 , 1991 ). Also, as time passes what exactly each of these four categories means may change or evolve as well.

The Pyramid of CSR

The four-part definition of CSR was originally published in 1979. In 1991, Carroll extracted the four-part definition and recast it in the form of a CSR pyramid. The purpose of the pyramid was to single out the definitional aspect of CSR and to illustrate the building block nature of the four part framework. The pyramid was selected as a geometric design because it is simple, intuitive, and built to withstand the test of time. Consequently, the economic responsibility was placed as the base of the pyramid because it is a foundational requirement in business. Just as the footings of a building must be strong to support the entire edifice, sustained profitability must be strong to support society’s other expectations of enterprises. The point here is that the infrastructure of CSR is built upon the premise of an economically sound and sustainable business.

At the same time, society is conveying the message to business that it is expected to obey the law and comply with regulations because law and regulations are society’s codification of the basic ground rules upon which business is to operate in a civil society. If one looks at CSR in developing countries, for example, whether a legal and regulatory framework exists or not significantly affects whether multinationals invest there or not because such a legal infrastructure is imperative to provide a foundation for legitimate business growth.

In addition, business is expected to operate in an ethical fashion. This means that business has the expectation, and obligation, that it will do what is right, just, and fair and to avoid or minimize harm to all the stakeholders with whom it interacts. Finally, business is expected to be a good corporate citizen, that is, to give back and to contribute financial, physical, and human resources to the communities of which it is a part. In short, the pyramid is built in a fashion that reflects the fundamental roles played and expected by business in society. Figure 1 presents a graphical depiction of Carroll’s Pyramid of CSR.

Ethics permeates the pyramid

Though the ethical responsibility is depicted in the pyramid as a separate category of CSR, it should also be seen as a factor which cuts through and saturates the entire pyramid. Ethical considerations are present in each of the other responsibility categories as well. In the Economic Responsibility category, for example, the pyramid implicitly assumes a capitalistic society wherein the quest for profits is viewed as a legitimate, just expectation. Capitalism, in other words, is an economic system which thinks of it as being ethically appropriate that owners or shareholders merit a return on their investments. In the Legal Responsibility category, it should be acknowledged that most laws and regulations were created based upon some ethical reasoning that they were appropriate. Most laws grew out of ethical issues, e.g., a concern for consumer safety, employee safety, the natural environment, etc., and thus once formalized they represented “codified ethics” for that society. And, of course, the Ethical Responsibility stands on its own in the four part model as a category that embraces policies and practices that many see as residing at a higher level of expectation than the minimums required by law. Minimally speaking, law might be seen as passive compliance. Ethics, by contrast, suggests a level of conduct that might anticipate future laws and in any event strive to do that which is considered above most laws, that which is driven by rectitude. Finally, Philanthropic Responsibilities are sometimes ethically motivated by companies striving to do the right thing. Though some companies pursue philanthropic activities as a utilitarian decision (e.g., strategic philanthropy) just to be seen as “good corporate citizens,” some do pursue philanthropy because they consider it to be the virtuous thing to do. In this latter interpretation, philanthropy is seen to be ethically motivated or altruistic in nature (Schwartz and Carroll 2003 ). In summary, ethical motivations and issues cut through and permeate all four of the CSR categories and thus assume a vital role in the totality of CSR.

Tensions and trade-offs

As companies seek to adequately perform with respect to their economic, legal, ethical and philanthropic responsibilities, tensions and trade-offs inevitably arise. How companies decide to balance these various responsibilities goes a long way towards defining their CSR orientation and reputation. The economic responsibility to owners or shareholders requires a careful trade-off between short term and long term profitability. In the short run, companies’ expenditures on legal, ethical and philanthropic obligations invariably will “appear” to conflict with their responsibilities to their shareholders. As companies expend resources on these responsibilities that appear to be in the primary interests of other stakeholders, a challenge to cut corners or seek out best long range advantages arises. This is when tensions and trade-offs arise. The traditional thought is that resources spent for legal, ethical and philanthropic purposes might necessarily detract from profitability. But, according to the “business case” for CSR, this is not a valid assumption or conclusion. For some time it has been the emerging view that social activity can and does lead to economic rewards and that business should attempt to create such a favorable situation (Chrisman and Carroll 1984 ).

The business case for CSR refers to the underlying arguments supporting or documenting why the business community should accept and advance the CSR cause. The business case is concerned with the primary question – What does the business community and commercial enterprises get out of CSR? That is, how do they benefit tangibly and directly from engaging in CSR policies, activities and practices (Carroll and Shabana 2010 ). There are many business case arguments that have been made in the literature, but four effective arguments have been made by Kurucz, et al., and these include cost and risk reductions, positive effects on competitive advantage, company legitimacy and reputation, and the role of CSR in creating win-win situations for the company and society (Kurucz et al. 2008 ). Other studies have enumerated the reasons for business to embrace CSR to include innovation, brand differentiation, employee engagement, and customer engagement. The purpose for business case thinking with respect to the Pyramid of CSR is to ameliorate the believed conflicts and tensions between and among the four categories of responsibilities. In short, the tensions and tradeoffs will continue to be important decision points, but they are not in complete opposition to one another as is often perceived.

The pyramid is an integrated, unified whole

The Pyramid of CSR is intended to be seen from a stakeholder perspective wherein the focus is on the whole not the different parts. The CSR pyramid holds that firms should engage in decisions, actions, policies and practices that simultaneously fulfill the four component parts. The pyramid should not be interpreted to mean that business is expected to fulfill its social responsibilities in some sequential, hierarchical, fashion, starting at the base. Rather, business is expected to fulfill all responsibilities simultaneously. The positioning or ordering of the four categories of responsibility strives to portray the fundamental or basic nature of these four categories to business’s existence in society. As said before, economic and legal responsibilities are required; ethical and philanthropic responsibilities are expected and desired. The representation being portrayed, therefore, is that the total social responsibility of business entails the concurrent fulfillment of the firm’s economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic responsibilities. Stated in the form of an equation, it would read as follows: Economic Responsibilities + Legal responsibilities + Ethical Responsibilities + Philanthropic Responsibilities = Total Corporate Social Responsibility. Stated in more practical and managerial terms, the CSR driven firm should strive to make a profit, obey the law, engage in ethical practices and be a good corporate citizen. When seen in this way, the pyramid is viewed as a unified or integrated whole (Carroll and Buchholtz 2015 ).

The pyramid is a sustainable stakeholder framework

Each of the four components of responsibility addresses different stakeholders in terms of the varying priorities in which the stakeholders might be affected. Economic responsibilities most dramatically impact shareholders and employees because if the business is not financially viable both of these groups will be significantly affected. Legal responsibilities are certainly important with respect to owners, but in today’s litigious society, the threat of litigation against businesses arise most often from employees and consumer stakeholders. Ethical responsibilities affect all stakeholder groups. Shareholder lawsuits are an expanding category. When an examination of the ethical issues business faces today is considered, they typically involve employees, customers, and the environment most frequently. Finally, philanthropic responsibilities most affect the community and nonprofit organizations, but also employees because some research has concluded that a company’s philanthropic involvement is significantly related to its employees’ morale and engagement.

The pyramid should be seen as sustainable in that these responsibilities represent long term obligations that overarch into future generations of stakeholders as well. Though the pyramid could be perceived to be a static snapshot of responsibilities, it is intended to be seen as a dynamic, adaptable framework the content of which focuses both on the present and the future. A consideration of stakeholders and sustainability, today, is inseparable from CSR. Indeed, there have been some appeals in the literature for CSR to be redefined as Corporate Stakeholder Responsibility and others have advocated Corporate Sustainability Responsibilities. These appeals highlight the intimate nature of these interrelated topics (Carroll and Buchholtz 2015 ). Furthermore, Ethical Corporation Magazine which emphasizes CSR in its Responsible Summit conferences integrates these two topics – CSR and Sustainability—as if they were one and, in fact, many business organizations today perceive them in this way; that is, to be socially responsible is to invest in the importance of sustainability which implicitly is concerned with the future. Annual corporate social performance reports frequently go by the titles of CSR and/or Sustainability Reports but their contents are undifferentiated from one another; in other words, the concepts are being used interchangeably by many.

Global applicability and different contexts

When Carroll developed his original four-part construct of CSR (1979) and then his pyramidal depiction of CSR (1991), it was clearly done with American-type capitalistic societies in mind. At that time, CSR was most prevalent in these more free enterprise societies. Since that time, several writers have proposed that the pyramid needs to be reordered to meet the conditions of other countries or smaller businesses. In 2007, Crane and Matten observed that all the levels of CSR depicted in Carroll’s pyramid play a role in Europe but they have a dissimilar significance and are interlinked in a somewhat different manner (Crane and Matten 2007 ). Likewise, Visser revisited Carroll’s pyramid in developing countries/continents, in particular, Africa, and argued that the order of the CSR layers there differ from the classic pyramid. He goes on to say that in developing countries, economic responsibility continues to get the most emphasis, but philanthropy is given second highest priority followed by legal and then ethical responsibilities (Visser 2011 ). Visser continues to contend that there are myths about CSR in developing countries and that one of them is that “CSR is the same the world over.” Following this, he maintains that each region, country or community has a different set of drivers of CSR. Among the “glocal” (global + local) drivers of CSR, he suggests that cultural tradition, political reform, socio-economic priorities, governance gaps, and crisis response are among the most important (Visser 2011 , p. 269). Crane, Matten and Spence do a nice job discussing CSR in a global context when they elaborate on CSR in different regions of the globe, CSR in developed countries, CSR in developing countries, and CSR in emerging/transitional economies (Crane et al. 2008 ).

In addition to issues being raised about the applicability of CSR and, therefore, the CSR pyramid in different localities, the same may be said for its applicability in different organizational contexts. Contexts of interest here might include private sector (large vs. small firms), public sector, and civil society organizations (Crane et al. 2008 ). In one particular theoretical article, Laura Spence sought to reframe Carroll’s CSR pyramid, enhancing its relevance for small business. Spence employed the ethic of care and feminist perspectives to redraw the four CSR domains by indicating that Carroll’s categories represented a masculinist perspective but that the ethic of care perspective would focus on different concerns. In this manner, she argued that the economic responsibility would be seen as “survival” in the ethic of care perspective; legal would be seen as “survival;” ethical would be recast as ethic of care; and philanthropy would continue to be philanthropy. It might be observed that these are not completely incompatible with Carroll’s categories. She then added a new category and that would be identified as “personal integrity.” She proposed that there could be at least four small business social responsibility pyramids – to self and family; to employees; to the local community; and to business partners (Spence 2016 ). Doubtless other researchers will continue to explore the applicability of the Pyramid of CSR to different global, situational, and organizational contexts. This is how theory and practice develops.

Conclusions

CSR has had a robust past and present. The future of CSR, whether it be viewed in the four part definitional construct, the Pyramid of CSR, or in some other format or nomenclature such as Corporate Citizenship, Sustainability, Stakeholder Management, Business Ethics, Creating Shared Value, Conscious Capitalism, or some other socially conscious semantics, seems to be on a sustainable and optimistic future. Though these other terminologies will sometimes be preferred by different supporters, CSR will continue to be the centerpiece of these competing and complementary frameworks (Carroll 2015 ). Though its enthusiasts would like to think of an optimistic or hopeful scenario wherein CSR would be adopted the world over and would be transformational everywhere it is practiced, the more probable scenario is that CSR will be consistent and stable and will continue to grow on a steady to slightly increasing trajectory. Four strong drivers of CSR taking hold in the 1990s and continuing forward have solidified its primacy. These include globalization, institutionalization, reconciliation with profitability, and academic proliferation (Carroll 2015b ). Globally, countries have been quickly adopting CSR practices in both developed and developing regions. CSR as a management strategy has become commonplace, formalized, integrated, and deeply assimilated into organizational structures, policies and practices. Primarily via “business case” reasoning, CSR has been more quickly adopted as a beneficial practice both to companies and society. The fourth factor driving CSR’s growth trajectory has been academic acceptance, enthusiasm, and proliferation. There has been an explosion of rigorous theory building and research on the topic across many disciplines and this is expected to continue and grow. In short, CSR, the Pyramid of CSR, and related models and concepts face an upbeat and optimistic future. Those seeking to refine these concepts will continue to do so.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Society and Business Anthology Copyright © 2019 by Various Authors is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Encyclopedia of Sustainable Management pp 1062–1069 Cite as

CSR Pyramid

- Annika Martens 7 &

- Annette Kleinfeld 8

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 22 November 2023

17 Accesses

CSR model ; Ethical dimensions of CSR ; Hierarchy of CSR dimensions ; Layers of CSR

The “CSR pyramid” by Archie B. Carroll is probably the most widespread and best-known model of CSR in the scholarly literature (see, e.g., Visser 2006 , p. 33; Verfürth 2016 , p. 32). It depicts a pyramid divided into four levels, which represent four kinds of responsibilities (economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic), that organizations, especially companies, hold toward their stakeholders and society at large. Together, these four responsibilities constitute “total CSR” as Carroll calls it (Carroll 1991 , p. 40).

Introduction

The famous CSR pyramid, published by Archie B. Carroll, shows four layers of responsibility in a hierarchical arrangement: an economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic responsibility. The article in which the model was published for the first time still ranks as one of the most frequently downloaded articles from Business Horizons in the last 90 days...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Aupperle, K. E., Carroll, A. B., & Hatfield, J. D. (1985). An empirical examination of the relationships between corporate social responsibility and profitability. Academy of Management Journal, 28 (2), 446–463.

Article Google Scholar

Carroll, A. B. (1979). A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate social performance. Academy of Management Review, 4 (4), 497–505.

Carroll, A. B. (1987). In search of the moral manager. Bu siness Horizons (March-April 1987), pp. 7–15.

Google Scholar

Carroll, A. B. (1991). The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizons (July–August, 1991), 34 (4), 39–48.

Carroll, A. B. (2004). Managing ethically with global stakeholders: A present and future challenge. Academy of Management Executive, 18 (2), 114–120.

Carroll, A. B. (2016). Carroll’s pyramid of CSR: taking another look. International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility 1, Article number 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40991-016-0004-6 . Accessed on the 4th of September 2019.

Carroll, A. B., Brown, J. A., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2018). Business & society: Ethics, sustainability & stakeholder management (10th ed.). Boston: Cengage Learning.