Essays About Empathy: Top 5 Examples Plus Prompts

If you’re writing essays about empathy, check out our essay examples and prompts to get started.

Empathy is the ability to understand and share other people’s emotions. It is the very notion which To Kill a Mockingbird character Atticus Finch was driving at when he advised his daughter Scout to “climb inside [other people’s] skin and walk around in it.”

Being able to feel the joy and sorrow of others and see the world from their perspective are extraordinary human capabilities that shape our social landscape. But beyond its effect on personal and professional relationships, empathy motivates kind actions that can trickle positive change across society.

If you are writing an article about empathy, here are five insightful essay examples to inspire you:

1. Do Art and Literature Cultivate Empathy? by Nick Haslam

2. empathy: overrated by spencer kornhaber, 3. in our pandemic era, why we must teach our children compassion by rebecca roland, 4. why empathy is a must-have business strategy by belinda parmar, 5. the evolution of empathy by frans de waal, 1. teaching empathy in the classroom., 2. how can companies nurture empathy in the workplace, 3. how can we develop empathy, 4. how do you know if someone is empathetic, 5. does empathy spark helpful behavior , 6. empathy vs. sympathy., 7. empathy as a winning strategy in sports. , 8. is there a decline in human empathy, 9. is digital media affecting human empathy, 10. your personal story of empathy..

“Exposure to literature and the sorts of movies that do not involve car chases might nurture our capacity to get inside the skins of other people. Alternatively, people who already have well-developed empathic abilities might simply find the arts more engaging…”

Haslam, a psychology professor, laid down several studies to present his thoughts and analysis on the connection between empathy and art. While one study has shown that literary fiction can help develop empathy, there’s still lacking evidence to show that more exposure to art and literature can help one be more empathetic. You can also check out these essays about character .

“Empathy doesn’t even necessarily make day-to-day life more pleasant, they contend, citing research that shows a person’s empathy level has little or no correlation with kindness or giving to charity.”

This article takes off from a talk of psychology experts on a crusade against empathy. The experts argue that empathy could be “innumerate, parochial, bigoted” as it zooms one to focus on an individual’s emotions and fail to see the larger picture. This problem with empathy can motivate aggression and wars and, as such, must be replaced with a much more innate trait among humans: compassion.

“Showing empathy can be especially hard for kids… Especially in times of stress and upset, they may retreat to focusing more on themselves — as do we adults.”

Roland encourages fellow parents to teach their kids empathy, especially amid the pandemic, where kindness is needed the most. She advises parents to seize everyday opportunities by ensuring “quality conversations” and reinforcing their kids to view situations through other people’s lenses.

“Mental health, stress and burnout are now perceived as responsibilities of the organization. The failure to deploy empathy means less innovation, lower engagement and reduced loyalty, as well as diluting your diversity agenda.”

The spike in anxiety disorders and mental health illnesses brought by the COVID-19 pandemic has given organizations a more considerable responsibility: to listen to employees’ needs sincerely. Parmar underscores how crucial it is for a leader to take empathy as a fundamental business strategy and provides tips on how businesses can adjust to the new norm.

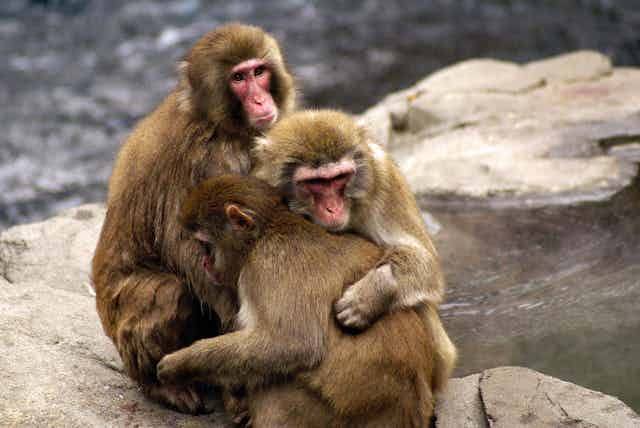

“The evolution of empathy runs from shared emotions and intentions between individuals to a greater self/other distinction—that is, an “unblurring” of the lines between individuals.”

The author traces the evolutionary roots of empathy back to our primate heritage — ultimately stemming from the parental instinct common to mammals. Ultimately, the author encourages readers to conquer “tribal differences” and continue turning to their emotions and empathy when making moral decisions.

10 Interesting Writing prompts on Essays About Empathy

Check out below our list of exciting prompts to help you buckle down to your writing:

This essay discuss teaching empathy in the classroom. Is this an essential skill that we should learn in school? Research how schools cultivate children’s innate empathy and compassion. Then, based on these schools’ experiences, provide tips on how other schools can follow suit.

An empathetic leader is said to help boost positive communication with employees, retain indispensable talent and create positive long-term outcomes. This is an interesting topic to research, and there are plenty of studies on this topic online with data that you can use in your essay. So, pick these best practices to promote workplace empathy and discuss their effectiveness.

Write down a list of deeds and activities people can take as their first steps to developing empathy. These activities can range from volunteering in their communities to reaching out to a friend in need simply. Then, explain how each of these acts can foster empathy and kindness.

Based on studies, list the most common traits, preferences, and behaviour of an empathetic person. For example, one study has shown that empathetic people prefer non-violent movies. Expound on this list with the support of existing studies. You can support or challenge these findings in this essay for a compelling argumentative essay. Make sure to conduct your research and cite all the sources used.

Empathy is a buzzword closely associated with being kind and helpful. However, many experts in recent years have been opining that it takes more than empathy to propel an act of kindness and that misplaced empathy can even lead to apathy. Gather what psychologists and emotional experts have been saying on this debate and input your analysis.

Empathy and sympathy have been used synonymously, even as these words differ in meaning. Enlighten your readers on the differences and provide situations that clearly show the contrast between empathy and sympathy. You may also add your take on which trait is better to cultivate.

Empathy has been deemed vital in building cooperation. A member who empathizes with the team can be better in tune with the team’s goals, cooperate effectively and help drive success. You may research how athletic teams foster a culture of empathy beyond the sports fields. Write about how coaches are integrating empathy into their coaching strategy.

Several studies have warned that empathy has been on a downward trend over the years. Dive deep into studies that investigate this decline. Summarize each and find common points. Then, cite the significant causes and recommendations in this study. You can also provide insights on whether this should cause alarm and how societies should address the problem.

There is a broad sentiment that social media has been driving people to live in a bubble and be less empathetic — more narcissistic. However, some point out that intensifying competition and increasing economic pressures are more to blame for reducing our empathetic feelings. Research and write about what experts have to say and provide a personal touch by adding your experience.

Acts of kindness abound every day. But sometimes, we fail to capture or take them for granted. Write about your unforgettable encounters with empathetic people. Then, create a storytelling essay to convey your personal view on empathy. This activity can help you appreciate better the little good things in life.

Check out our general resource of essay writing topics and stimulate your creative mind!

See our round-up of the best essay checkers to ensure your writing is error-free.

Yna Lim is a communications specialist currently focused on policy advocacy. In her eight years of writing, she has been exposed to a variety of topics, including cryptocurrency, web hosting, agriculture, marketing, intellectual property, data privacy and international trade. A former journalist in one of the top business papers in the Philippines, Yna is currently pursuing her master's degree in economics and business.

View all posts

Understanding others’ feelings: what is empathy and why do we need it?

Senior Lecturer in Social Neuroscience, Monash University

Disclosure statement

Pascal Molenberghs receives funding from the Australian Research Council (ARC Discovery Early Career Research Award: DE130100120) and Heart Foundation (Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship: 1000458).

Monash University provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

This is the introductory essay in our series on understanding others’ feelings. In it we will examine empathy, including what it is, whether our doctors need more of it, and when too much may not be a good thing.

Empathy is the ability to share and understand the emotions of others. It is a construct of multiple components, each of which is associated with its own brain network . There are three ways of looking at empathy.

First there is affective empathy. This is the ability to share the emotions of others. People who score high on affective empathy are those who, for example, show a strong visceral reaction when watching a scary movie.

They feel scared or feel others’ pain strongly within themselves when seeing others scared or in pain.

Cognitive empathy, on the other hand, is the ability to understand the emotions of others. A good example is the psychologist who understands the emotions of the client in a rational way, but does not necessarily share the emotions of the client in a visceral sense.

Finally, there’s emotional regulation. This refers to the ability to regulate one’s emotions. For example, surgeons need to control their emotions when operating on a patient.

Another way to understand empathy is to distinguish it from other related constructs. For example, empathy involves self-awareness , as well as distinction between the self and the other. In that sense it is different from mimicry, or imitation.

Many animals might show signs of mimicry or emotional contagion to another animal in pain. But without some level of self-awareness, and distinction between the self and the other, it is not empathy in a strict sense. Empathy is also different from sympathy, which involves feeling concern for the suffering of another person and a desire to help.

That said, empathy is not a unique human experience. It has been observed in many non-human primates and even rats .

People often say psychopaths lack empathy but this is not always the case. In fact, psychopathy is enabled by good cognitive empathic abilities - you need to understand what your victim is feeling when you are torturing them. What psychopaths typically lack is sympathy. They know the other person is suffering but they just don’t care.

Research has also shown those with psychopathic traits are often very good at regulating their emotions .

Why do we need it?

Empathy is important because it helps us understand how others are feeling so we can respond appropriately to the situation. It is typically associated with social behaviour and there is lots of research showing that greater empathy leads to more helping behaviour.

However, this is not always the case. Empathy can also inhibit social actions, or even lead to amoral behaviour . For example, someone who sees a car accident and is overwhelmed by emotions witnessing the victim in severe pain might be less likely to help that person.

Similarly, strong empathetic feelings for members of our own family or our own social or racial group might lead to hate or aggression towards those we perceive as a threat. Think about a mother or father protecting their baby or a nationalist protecting their country.

People who are good at reading others’ emotions, such as manipulators, fortune-tellers or psychics, might also use their excellent empathetic skills for their own benefit by deceiving others.

Interestingly, people with higher psychopathic traits typically show more utilitarian responses in moral dilemmas such as the footbridge problem. In this thought experiment, people have to decide whether to push a person off a bridge to stop a train about to kill five others laying on the track.

The psychopath would more often than not choose to push the person off the bridge. This is following the utilitarian philosophy that holds saving the life of five people by killing one person is a good thing. So one could argue those with psychopathic tendencies are more moral than normal people – who probably wouldn’t push the person off the bridge – as they are less influenced by emotions when making moral decisions.

How is empathy measured?

Empathy is often measured with self-report questionnaires such as the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) or Questionnaire for Cognitive and Affective Empathy (QCAE).

These typically ask people to indicate how much they agree with statements that measure different types of empathy.

The QCAE, for instance, has statements such as, “It affects me very much when one of my friends is upset”, which is a measure of affective empathy.

Cognitive empathy is determined by the QCAE by putting value on a statement such as, “I try to look at everybody’s side of a disagreement before I make a decision.”

Using the QCAE, we recently found people who score higher on affective empathy have more grey matter, which is a collection of different types of nerve cells, in an area of the brain called the anterior insula.

This area is often involved in regulating positive and negative emotions by integrating environmental stimulants – such as seeing a car accident - with visceral and automatic bodily sensations.

We also found people who score higher on cognitive empathy had more grey matter in the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex.

This area is typically activated during more cognitive processes, such as Theory of Mind, which is the ability to attribute mental beliefs to yourself and another person. It also involves understanding that others have beliefs, desires, intentions, and perspectives different from one’s own.

Can empathy be selective?

Research shows we typically feel more empathy for members of our own group , such as those from our ethnic group. For example, one study scanned the brains of Chinese and Caucasian participants while they watched videos of members of their own ethnic group in pain. They also observed people from a different ethnic group in pain.

The researchers found that a brain area called the anterior cingulate cortex, which is often active when we see others in pain, was less active when participants saw members of ethnic groups different from their own in pain.

Other studies have found brain areas involved in empathy are less active when watching people in pain who act unfairly . We even see activation in brain areas involved in subjective pleasure , such as the ventral striatum, when watching a rival sport team fail.

Yet, we do not always feel less empathy for those who aren’t members of our own group. In our recent study , students had to give monetary rewards or painful electrical shocks to students from the same or a different university. We scanned their brain responses when this happened.

Brain areas involved in rewarding others were more active when people rewarded members of their own group, but areas involved in harming others were equally active for both groups.

These results correspond to observations in daily life. We generally feel happier if our own group members win something, but we’re unlikely to harm others just because they belong to a different group, culture or race. In general, ingroup bias is more about ingroup love rather than outgroup hate.

Yet in some situations, it could be helpful to feel less empathy for a particular group of people. For example, in war it might be beneficial to feel less empathy for people you are trying to kill, especially if they are also trying to harm you.

To investigate, we conducted another brain imaging study . We asked people to watch videos from a violent video game in which a person was shooting innocent civilians (unjustified violence) or enemy soldiers (justified violence).

While watching the videos, people had to pretend they were killing real people. We found the lateral orbitofrontal cortex, typically active when people harm others, was active when people shot innocent civilians. The more guilt participants felt about shooting civilians, the greater the response in this region.

However, the same area was not activated when people shot the soldier that was trying to kill them.

The results provide insight into how people regulate their emotions. They also show the brain mechanisms typically implicated when harming others become less active when the violence against a particular group is seen as justified.

This might provide future insights into how people become desensitised to violence or why some people feel more or less guilty about harming others.

Our empathetic brain has evolved to be highly adaptive to different types of situations. Having empathy is very useful as it often helps to understand others so we can help or deceive them, but sometimes we need to be able to switch off our empathetic feelings to protect our own lives, and those of others.

Tomorrow’s article will look at whether art can cultivate empathy.

- Theory of mind

- Emotional contagion

- Understanding others' feelings

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

School of Social Sciences – Human Geography opportunities

School of Social Sciences – Criminology opportunities

School of Social Sciences – Academic appointment opportunities

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

Home — Essay Samples — Life — Emotions & Feelings — Empathy

Empathy Essays

Hook examples for empathy essays, anecdotal hook.

"As I witnessed a stranger's act of kindness towards a struggling neighbor, I couldn't help but reflect on the profound impact of empathy—the ability to connect with others on a deeply human level."

Rhetorical Question Hook

"What does it mean to truly understand and share in the feelings of another person? The concept of empathy prompts us to explore the complexities of human connection."

Startling Statistic Hook

"Studies show that empathy plays a crucial role in building strong relationships, fostering teamwork, and reducing conflicts. How does empathy contribute to personal and societal well-being?"

"'Empathy is seeing with the eyes of another, listening with the ears of another, and feeling with the heart of another.' This profound quote encapsulates the essence of empathy and its significance in human interactions."

Historical Hook

"From ancient philosophies to modern psychology, empathy has been a recurring theme in human thought. Exploring the historical roots of empathy provides deeper insights into its importance."

Narrative Hook

"Join me on a journey through personal stories of empathy, where individuals bridge cultural, social, and emotional divides. This narrative captures the essence of empathy in action."

Psychological Impact Hook

"How does empathy impact mental health, emotional well-being, and interpersonal relationships? Analyzing the psychological aspects of empathy adds depth to our understanding."

Social Empathy Hook

"In a world marked by diversity and societal challenges, empathy plays a crucial role in promoting understanding and social cohesion. Delving into the role of empathy in society offers important insights."

Empathy in Literature and Arts Hook

"How has empathy been depicted in literature, art, and media throughout history? Exploring its representation in the creative arts reveals its enduring significance in culture."

Teaching Empathy Hook

"What are effective ways to teach empathy to individuals of all ages? Examining strategies for nurturing empathy offers valuable insights for education and personal growth."

Humility and Values

The choice of compassion: cultivating empathy, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

Poem Analysis: "Any Human to Another"

How empathy and understanding others is important for our society, the key components of empathy, importance of the empathy in my family, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

The Importance of Promoting Empathy in Children

Steps for developing empathy in social situations, the impacts of digital media on empathy, the contributions of technology to the decline of human empathy, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

The Role of Empathy in Justice System

Importance of empathy for blind people, the most effective method to tune in with empathy in the classroom, thr way acts of kindness can change our lives, the power of compassion and its main aspects, compassion and empathy in teaching, acts of kindness: importance of being kind, the concept of empathy in "do androids dream of electric sheep", the vital values that comprise the definition of hero, critical analysis of kwame anthony appiah’s theory of conversation, development of protagonist in philip k. novel "do androids dream of electric sheep", talking about compassion in 100 words, barbara lazear aschers on compassion, my purpose in life is to help others: helping behavior, adolescence stage experience: perspective taking and empathy, random act of kindness, helping others in need: importance of prioritizing yourself, toni cade bambara the lesson summary, making a positive impact on others: the power of influence, patch adams reflection paper.

Empathy is the capacity to understand or feel what another person is experiencing from within their frame of reference, that is, the capacity to place oneself in another's position.

Types of empathy include cognitive empathy, emotional (or affective) empathy, somatic empathy, and spiritual empathy.

Empathy-based socialization differs from inhibition of egoistic impulses through shaping, modeling, and internalized guilt. Empathetic feelings might enable individuals to develop more satisfactory interpersonal relations, especially in the long-term. Empathy-induced altruism can improve attitudes toward stigmatized groups, and to improve racial attitudes, and actions toward people with AIDS, the homeless, and convicts. It also increases cooperation in competitive situations.

Empathetic people are quick to help others. Painkillers reduce one’s capacity for empathy. Anxiety levels influence empathy. Meditation and reading may heighten empathy.

Relevant topics

- Responsibility

- Forgiveness

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

The concept of empathy is used to refer to a wide range of psychological capacities that are thought of as being central for constituting humans as social creatures allowing us to know what other people are thinking and feeling, to emotionally engage with them, to share their thoughts and feelings, and to care for their well–being. Ever since the eighteenth century, due particularly to the influence of the writings of David Hume and Adam Smith, those capacities have been at the center of scholarly investigations into the underlying psychological basis of our social and moral nature. Yet, the concept of empathy is of relatively recent intellectual heritage. Moreover, since researchers in different disciplines have focused their investigations on very specific aspects of the broad range of empathy-related phenomena, one should probably not be surprised by a certain amount of conceptual confusion and a multiplicity of definitions associated with the empathy concept in a number of different scientific and non-scientific discourses. The purpose of this entry is to clarify the empathy concept by surveying its history in various philosophical and psychological discussions and by indicating why empathy was and should be regarded to be of such central importance in understanding human agency in ordinary contexts, in the human sciences, and for the constitution of ourselves as social and moral agents. More specifically, after a short historical introduction articulating the philosophical context within which the empathy concept was coined, the second and third sections will discuss the epistemic dimensions associated with our empathic capacities. They will address the contention that empathy is the primary epistemic means for knowing other minds and that it should be viewed as the unique method distinguishing the human from the natural sciences. Sections 4 and 5 will then focus on claims that view empathy as the fundamental social glue and that understand empathy as the main psychological mechanism enabling us to establish and maintain social relations and taking an evaluative stance towards each other.

1. Historical Introduction

2.1 mirror neurons, simulation, and the discussion of empathy in the contemporary theory of mind debate, 3.1 the critique of empathy in the context of a hermeneutic conception of the human sciences, 3.2 the critique of empathy within the context of a naturalist conception of the human sciences, 4. empathy as a topic of scientific exploration in psychology, 5.1 empathy and altruistic motivation, 5.2 empathy, its partiality, susceptibility to bias, and moral agency, 5.3 empathy, moral judgment, and the authority of moral norms, other internet resources, related entries.

Before the psychologist Edward Titchener (1867–1927) introduced the term “empathy” in 1909 into the English language as the translation of the German term “Einfühlung” (or “feeling into”), “sympathy”was the term commonly used to refer to empathy-related phenomena. If one were to point to a conceptual core for understanding these phenomena, it is probably best to point to David Hume’s dictum that “the minds of men are mirrors to one another,”(Hume 1739–40 [1978], 365) since in encountering other persons, humans can resonate with and recreate that person’s thoughts and emotions on different dimensions of cognitive complexity. While, as we will see, not everybody shares such resonance conception of empathy(some philosophers in the phenomenological tradition emphatically reject it), it certainly constitutes the center of Theodor Lipps’s understanding, who Titchener had in mind in his translation of “Einfühlung” as “empathy.”

Theodor Lipps (1851–1914)was also very familiar with the work of David Hume (see the introduction to Coplan and Goldie 2011 in this respect). More importantly, it was Theodor Lipps, whose work transformed empathy/Einfühlung from a concept of nineteenth century German aesthetics into a central category of the philosophy of the social and human sciences. To understand this transformation we first need to appreciate the reasons why philosophers of the nineteenth century thought it necessary to appeal to empathy in order to account for our ability to appreciate natural objects and artefacts in an aesthetic manner. According to the dominant (even though not universally accepted) positivistic and empiricist conception, sense data constitute the fundamental basis for our investigation of the world. Yet from a phenomenological perspective, our perceptual encounter with aesthetic objects and our appreciation of them as being beautiful—our admiration of a beautiful sunset, for example—seems to be as direct as our perception of an object as being red or square. By appealing to the psychological mechanisms of empathy, philosophers intended to provide an explanatory account of the phenomenological immediacy of our aesthetic appreciation of objects. More specifically, for Lipps, our empathic encounter with external objects trigger inner “processes” that give rise to experiences similar to ones that I have when I engage in various activities involving the movement of my body. Since my attention is perceptually focused on the external object, I experience them—or I automatically project my experiences—as being in the object. If those experiences are in some way apprehended in a positive manner and as being in some sense life-affirming, I perceive the object as beautiful, otherwise as ugly. In the first case, Lipps speaks of positive; in the later of negative empathy. Lipps also characterizes our experience of beauty as “objectified self-enjoyment,” since we are impressed by the “vitality” and “life potentiality” that lies in the perceived object (Lipps 1906, 1903 a,b. For the contemporary discussion of empathy’s role in aesthetics see particularly Breithaupt 2009; Coplan and Goldie 2011 (Part II); Curtis & Koch 2009; and Keen 2007. For a recent history of the empathy concept see also Lanzoni 2018).

In his Aesthetik, Lipps closely links our aesthetic perception and our perception of another embodied person as a minded creature. The nature of aesthetic empathy is always the “experience of another human” (1905, 49) . We appreciate another object as beautiful because empathy allows us to see it in analogy to another human body. Similarly, we recognize another organism as a minded creature because of empathy. Empathy in this context is more specifically understood as a phenomenon of “inner imitation,” where my mind mirrors the mental activities or experiences of another person based on the observation of his bodily activities or facial expressions. Empathy is ultimately based on an innate disposition for motor mimicry, a fact that is well established in the psychological literature and was already noticed by Adam Smith (1853). Even though such a disposition is not always externally manifested, Lipps suggests that it is always present as an inner tendency giving rise to similar kinaesthetic sensations in the observer as felt by the observed target. In seeing the angry face of another person we instinctually have a tendency of imitating it and of “imitating” her anger in this manner. Since we are not aware of such tendencies, we see the anger in her face (Lipps 1907). Despite the fact that Lipps’s primary examples of empathy focus on the recognition of emotions expressed in bodily gestures or facial expressions, his conception of empathy should not be understood as being limited to such cases. As his remarks about intellectual empathy suggest (1903b/05), he regards our recognition of all mental activities—insofar as they are activities requiring human effort—as being based on empathy or on inner imitation (See also the introductory chapter in Stueber 2006).

2. Empathy and the Philosophical Problem of Other Minds

It was indeed Lipps’s claim that empathy should be understood as the primary epistemic means for gaining knowledge of other minds that was the focus of a lively debate among philosophers at the beginning of the 20 th century (Prandtl 1910, Stein 1917, Scheler 1973). Even philosophers, who did not agree with Lipps’s specific explication, found the concept of empathy appealing because his argument for his position was closely tied to a thorough critique of what was widely seen at that time as the only alternative for conceiving of knowledge of other minds, that is, Mill’s inference from analogy. Traditionally, the inference from analogy presupposes a Cartesian conception of the mind according to which access to our own mind is direct and infallible, whereas knowledge of other minds is inferential, fallible, and based on evidence about other persons’ observed physical behavior. More formally one can characterize the inference from analogy as consisting of the following premises or steps.

i.) Another person X manifests behavior of type B . ii.) In my own case behavior of type B is caused by mental state of type M . iii.) Since my and X ’s outward behavior of type B is similar, it has to have similar inner mental causes. (It is thus assumed that I and the other persons are psychologically similar in the relevant sense.) Therefore: The other person’s behavior ( X ’s behavior) is caused by a mental state of type M .

Like Wittgenstein, but predating him considerably, Lipps argues in his 1907 article “Das Wissen von fremden Ichen” that the inference from analogy falls fundamentally short of solving the philosophical problem of other minds. Lipps does not argue against the inference from analogy because of its evidentially slim basis, but because it does not allow us to understand its basic presupposition that another person has a mind that is psychologically similar to our own mind. The inference from analogy thus cannot be understood as providing us with evidence for the claim that the other person has mental states like we do because, within its Cartesian framework, we are unable to conceive of other minds in the first place. For Lipps, analogical reasoning requires the contradictory undertaking of inferring another person’s anger and sadness on the basis of my sadness and anger, yet to think of that sadness and anger simultaneously as something “absolutely different” from my anger and sadness. More generally, analogical inference is a contradictory undertaking because it entails “entertaining a completely new thought about an I, that however is not me, but something absolutely different” (Lipps 1907, 708, my translation).

Yet while Lipps diagnoses the problem of the inference of analogy within the context of a Cartesian conception of the mind quite succinctly, he fails to explain how empathy is able to provide us with an epistemically sanctioned understanding of other minds or why our “feeling into” the other person’s mind is more than a mere projection. More importantly, Lipps does not sufficiently explain why empathy does not encounter similar problems to the ones diagnosed for the inference from analogy and how empathy allows us to conceive of other persons as having a mind similar to our own if we are directly acquainted only with our own mental states(See Stueber 2006). Wittgenstein’s critique of the inference from analogy is in the end more penetrating because he recognizes that its problem depends on a Cartesian account of mental concepts. If my grasp of a mental concept is exclusively constituted by me experiencing something in a certain way, then it is impossible for me to conceive of how that very same concept can be applied to somebody else, given that I cannot experience somebody else’s mental states. I therefore cannot conceive of how another person can be in the same mental state as I am because that would require that I can conceive of my mental state as something, which I do not experience. But according to the Cartesian conception this seems to be a conceptually impossible task. Moreover, if one holds on to a Cartesian conception of the mind, it is not clear how appealing to empathy, as conceived of by Lipps, should help us in conceiving of mental states as belonging to another mind.

Within the phenomenological tradition, the above shortcomings of Lipps’s position of empathy were quite apparent (see for example Stein 1917, 24 and Scheler 1973, 236). Yet despite the fact that they did not accept Lipps’s explication of empathy as being based on mechanisms of inner resonance and projection, authors within the phenomenological tradition of philosophy were persuaded by Lipps’s critique of the inference from analogy. For that very reason, Husserl and Stein, for example, continued using the concept of empathy and regarded empathy as an irreducible “type of experiential act sui generis” (Stein 1917, 10), which allows us to view another person as being analogous to ourselves without this “analogizing apprehension” constituting an inference of analogy (Husserl 1931 [1963], 141). Scheler went probably the furthest in rejecting the Cartesian framework in thinking about the apprehension of other minds, while keeping committed to something like the concept of empathy. [ 1 ] (In order to contrast his position from Lipps, Scheler however preferred to use the term “nachfühlen” rather than “einfühlen.”) For Scheler, the fundamental mistake of the debate about the apprehension of other minds consists in the fact that it does not take seriously certain phenomenological facts. Prima facie, we do not encounter merely the bodily movements of another person. Rather, we are directly recognizing specific mental states because they are characteristically expressed in states of the human body; in facial expressions, in gestures, in the tone of voice, and so on. Empathy within the phenomenological tradition then is not conceived of as a resonance phenomenon requiring the observer to recreate the mental states of the other person in his or her own mind but as a special perceptual act (See Scheler 1973, particularly 232–258; For a succinct explication of the debate about empathy in the phenomenological tradition consult Zahavi 2010)

The idea that empathy understood as inner imitation is the primary epistemic means for understanding other minds has however been revived in the 1980’s by simulation theorists in the context of the interdisciplinary debate about folk psychology; an empirically informed debate about how best to describe the underlying causal mechanisms of our folk psychological abilities to interpret, explain, and predict other agents. (See Davies and Stone 1995). In contrast to theory theory, simulation theorists conceive of our ordinary mindreading abilities as an ego-centric method and as a “knowledge–poor” strategy, where I do not utilize a folk psychological theory but use myself as a model for the other person’s mental life. It is not the place here to discuss the contemporary debate extensively, but it has to be emphasized that contemporary simulation theorists vigorously discuss how to account for our grasp of mental concepts and whether simulation theory is committed to Cartesianism. Whereas Goldman (2002, 2006) links his version of simulation theory to a neo-Cartesian account of mental concepts, other simulation theorists develop versions of simulation theory that are not committed to a Cartesian conception of the mind. (Gordon 1995a, b, and 2000; Heal 2003; and Stueber 2006, 2012).

Moreover, neuroscientific findings according to which so called mirror neurons play an important role in recognizing another person’s emotional states and in understanding the goal-directedness of his behavior have been understood as providing empirical evidence for Lipps’ idea of empathy as inner imitation. With the help of the term “mirror neuron,” scientists refer to the fact that there is significant overlap between neural areas of excitation that underlie our observation of another person’s action and areas that are stimulated when we execute the very same action. A similar overlap between neural areas of excitation has also been established for our recognition of another person’s emotion based on his facial expression and our experiencing the emotion. (For a survey on mirror neurons see Gallese 2003a and b, Goldman 2006, chap. 6; Keysers 2011; Rizzolatti and Craighero 2004; and particularly Rizzolatti and Sinigaglia 2008). Since the face to face encounter between persons is the primary situation within which human beings recognize themselves as minded creatures and attribute mental states to others, the system of mirror neurons has been interpreted as playing a causally central role in establishing intersubjective relations between minded creatures. For that very reason, the neuroscientist Gallese thinks of mirror neurons as constituting what he calls the “shared manifold of intersubjectivity” (Gallese 2001, 44). Stueber (2006, chap. 4)—inspired by Lipps’s conception of empathy as inner imitation—refers to mirror neurons as mechanisms of basic empathy; [ 2 ] as mechanisms that allow us to apprehend directly another person’s emotions in light of his facial expressions and that enable us to understand his bodily movements as goal-directed actions, that is, as being directed towards an external object like a person reaching for the cup. The evidence from mirror neurons—and the fact that in perceiving other people we use very different neurobiological mechanisms than in the perception of physical objects—does suggest that in our primary perceptual encounter with the world we do not merely encounter physical objects. Rather, even on this basic level, we distinguish already between mere physical objects and objects that are more like us (See also Meltzoff and Brooks 2001). The mechanisms of basic empathy have to be seen as Nature’s way of dissolving one of the principal assumptions of the traditional philosophical discussion about other minds shared by opposing positions such as Cartesianism and Behaviorism; that is, that we perceive other people primarily as physical objects and do not distinguish already on the perceptual level between physical objects like trees and minded creatures like ourselves. Mechanisms of basic empathy might therefore be interpreted as providing us with a perceptual and non-conceptual basis for developing an intersubjectively accessible folk psychological framework that is applicable to the subject and observed other (Stueber 2006, 142–45).

It needs to be acknowledged however that this interpretation of mirror neurons crucially depends on the assumption that the primary function of mirror neurons consists in providing us with a cognitive grasp of another person’s actions and emotions. This interpretation has however been criticized by researchers and philosophers who think that neural resonance presupposes rather than provides us with an understanding of what is going on in the minds of others (Csibra 2007, Hickok 2008 and 2014). They have also pointed out that in observing another person’s emotion or behavior, we never fully “mirror” another person’s neural stimulation. The neuroscientist Jean Decety has argued that in observing another person’s pain our vicariously stimulated pain matrix is not sensitive to the phenomenal quality of pain. Rather it is sensitive to pain as an indicator of “aversion and withdrawal when exposed to danger and threats”(Decety and Cowell 2015, 6 and Decety 2010). At least as far as empathy for pain is concerned, our neural resonance is also modulated by a variety of contextual factors, such as how close we feel to the observed subject, whether we regard the pain to be morally justified (as in the case of punishment, for example) or whether we regard it as unavoidable and necessary, such as in a medical procedure (Singer and Lamm 2009; but see also Allen 2010, Borg 2007, Debes 2010, Gallese 2016, Goldman 2009, Iacoboni 2011, Jacob 2008, Rizzolatti and Sinigaglia 2016, and Stueber 2012a).

Yet it should be noted that everyday mindreading is not restricted to the realm of basic empathy. Ordinarily we not only recognize that other persons are afraid or that they are reaching for a particular object. We understand their behavior in more complex social contexts in terms of their reasons for acting using the full range of psychological concepts including the concepts of belief and desire. Evidence from neuroscience shows that these mentalizing tasks involve very different neuronal areas such as the medial prefrontal cortex, temporoparietal cortex, and the cingulate cortex. (For a survey see Kain and Perner 2003; Frith and Frith 2003; Zaki and Ochsner 2012). Low level mindreading in the realm of basic empathy has therefore to be distinguished from higher levels of mindreading (Goldman 2006). It is clear that low level forms of understanding other persons have to be conceived of as being relatively knowledge– poor as they do not involve a psychological theory or complex psychological concepts. How exactly one should conceive of high level mindreading abilities, whether they involve primarily knowledge–poor simulation strategies or knowledge–rich inferences is controversially debated within the contemporary debate about our folk psychological mindreading abilities(See Davies and Stone 1995, Gopnik and Meltzoff 1997, Gordon 1995, Currie and Ravenscroft 2002, Heal 2003, Nichols and Stich 2003, Goldman 2006, and Stueber 2006). Simulation theorists, however, insist that even more complex forms of understanding other agents involve resonance phenomena that engage our cognitively intricate capacities of imaginatively adopting the perspective of another person and reenacting or recreating their thought processes (For various forms of perspective-taking see Coplan 2011 and Goldie 2000). Accordingly, simulation theorists distinguish between different types of empathy such as between basic and reenactive empathy (Stueber 2006) or between mirroring and reconstructive empathy (Goldman 2011). Interestingly, the debate about how to conceive of these more complex forms of mindreading resonates with the traditional debate about whether empathy is the unique method of the human sciences and whether or not one has to strictly distinguish between the methods of the human and the natural sciences. Equally noteworthy is the fact that in the contemporary theory of mind debate voices have grown louder that assert that the contemporary theory of mind debate fundamentally misconceives of the nature of social cognition. In light of insights from the phenomenological and hermeneutic traditions in philosophy, they claim that on the most basic level empathy should not be conceived of as a resonance phenomenon but as a type of direct perception. (See particularly Zahavi 2010; Zahavi and Overgaard 2012, but Jacob 2011 for a response). More complex forms of social cognition are also not to be understood as being based on either theory or empathy/simulation, rather they are better best conceived of as the ability to directly fit observed units of actions into larger narrative or cultural frameworks (For this debate see Gallagher 2012, Gallagher and Hutto 2008, Hutto 2008, and Seemann 2011, Stueber 2011 and 2012a, and various articles in Matravers and Waldow 2018). For skepticism about empathic perspective-taking understood as a complete identification with the perspective of the other person see also Goldie 2011). Regardless of how one views this specific debate it should be clear that ideas about mindreading developed originally by proponents of empathy at the beginning of the 20 th century can no longer be easily dismissed and have to be taken seriously.

3. Empathy as the Unique Method of the Human Sciences

At the beginning of the 20 th century, empathy understood as a non-inferential and non-theoretical method of grasping the content of other minds became closely associated with the concept of understanding (Verstehen); a concept that was championed by the hermeneutic tradition of philosophy concerned with explicating the methods used in grasping the meaning and significance of texts, works of arts, and actions. (For a survey of this tradition see Grondin 1994). Hermeneutic thinkers insisted that the method used in understanding the significance of a text or a historical event has to be fundamentally distinguished from the method used in explaining an event within the context of the natural sciences. This methodological dualism is famously expressed by Droysen in saying that “historical research does not want to explain; that is, derive in a form of an inferential argument, rather it wants to understand” (Droysen 1977, 403), and similarly in Dilthey’s dictum that “we explain nature, but understand the life of the soul” (Dilthey 1961, vol. 5, 144). Yet Droysen and authors before him never conceived of understanding solely as an act of mental imitation or solely as an act of imaginatively “transporting” oneself into the point of view of another person. Such “psychological interpretation” as Schleiermacher (1998) used to call it, was conceived of as constituting only one aspect of the interpretive method used by historians. Other tasks mentioned in this context involved critically evaluating the reliability of historical sources, getting to know the linguistic conventions of a language, and integrating the various elements derived from historical sources into a consistent narrative of a particular epoch. The differences between these various aspects of the interpretive procedure were however downplayed in the early Dilthey. For him, grasping the significance of any cultural fact had to be understood as a mental act of “transposition.” (See for example Dilthey 1961, vol. 5, 263–265). .

Ironically, the close association of the concepts of empathy and understanding and the associated claim that empathy is the sole and unique method of the human sciences also facilitated the decline of the empathy concept and its almost utter disregard by philosophers of the human and social sciences later on, in both the analytic and continental/hermeneutic traditions of philosophy. Within both traditions, proponents of empathy were—for very different reasons—generally seen as advocating an epistemically naïve and insufficiently broad conception of the methodological proceedings in the human sciences. As a result, most philosophers of the human and social sciences maintained their distance from the idea that empathy is central for our understanding of other minds and mental phenomena. Notable exceptions in this respect are R.G. Collingwood and his followers, who suggested that reenacting another person’s thoughts is necessary for understanding them as rational agents (Collingwood 1946, Dray 1957 and 1995). Notice however that in contrast to the contemporary debate about folk psychology, the debate about empathy in the philosophy of social science is not concerned with investigating underlying causal mechanisms. Rather, it addresses normative questions of how to justify a particular explanation or interpretation.

Philosophers arguing for a hermeneutic conception of the human and social sciences insist on a strict methodological division between the human and the natural sciences. [ 3 ] Yet they nowadays favor the concept of understanding (Verstehen) and reject the earlier identification of understanding and empathy for two specific reasons. First, empathy is no longer seen as the unique method of the human sciences because facts of significance, which a historian or an interpreter of literary and non-literary texts are interested in, do not solely depend on facts within the individual mind. A historian, for example, is not bound by the agent’s perspective in telling the story of a particular historical time period(Danto 1965). Similarly, philosophers such as Hans Georg Gadamer, have argued that the significance of a text is not tied to the author’s intentions in writing the text. In reading a text by Shakespeare or Plato we are not primarily interested in finding out what Plato or Shakespeare said but what these texts themselves say.(Gadamer 1989; for a critical discussion see Skinner (in Tully 1988); “Introduction” in Kögler and Stueber 2000; and Stueber 2002).

The above considerations, however, do not justify the claim that empathy has no role to play within the context of the human sciences. It justifies merely the claim that empathy cannot be their only method, at least as long as one admits that recognizing the thoughts of individual agents has to play some role in the interpretive project of the human sciences. Accordingly, a second reason against empathy is also emphasized. Conceiving of understanding other agents as being based on empathy is seen as an epistemically extremely naïve conception of the interpretation of individual agents, since it seems to conceive of understanding as a mysterious meeting of two individual minds outside of any cultural context. Individual agents are always socially and culturally embedded creatures. Understanding other agents thus presupposes an understanding of the cultural context within which an agent functions. Moreover, in the interpretive situation of the human sciences, the cultural background of the interpreter and the person, who has to be interpreted, can be very different. In that case, I can not very easily put myself in the shoes of the other person and imitate his thoughts in my mind. If understanding medieval knights, to use an example of Winch (1958), requires me to think exactly as the medieval knight did, then it is not clear how such a task can be accomplished from an interpretive perspective constituted by very different cultural presuppositions. Making sense of other minds has, therefore, to be seen as an activity that is a culturally mediated one; a fact that empathy theorists according to this line of critique do not sufficiently take into account when they conceive of understanding other agents as a direct meeting of minds that is independent of and unaided by information about how these agents are embedded in a broader social environment. (See Stueber 2006, chap.6, Zahavi 2001, 2005; for the later Dilthey see Makreel 2000. For a critical discussion of whether the concept of understanding without recourse to empathy is useful for marking an epistemic distinction between the human and natural sciences consult also Stueber 2012b. Within the context of anthropology, Hollan and Throop argue that empathy is best understood as a dynamic, culturally situated, temporally extended, and dialogical process actively involving not only the interpreter but also his or her interpretee. See Hollan 20012; Hollan and Throop 2008, 2001; Throop 2010).).

Philosophers, who reject the methodological dualism between the human and the natural sciences as argued for in the hermeneutic context, are commonly referred to as naturalists in the philosophy of social science. They deny that the distinction between understanding and explanation points to an important methodological difference. Even in the human or social sciences, the main point of the scientific endeavor is to provide epistemically justified explanations (and predictions) of observed or recorded events (see also Henderson 1993). At most, empathy is granted a heuristic role in the context of discovery. It however can not play any role within the context of justification. As particularly Hempel (1965) has argued, to explain an event involves—at least implicitly—an appeal to law-like regularities providing us with reasons for expecting that an event of a certain kind will occur under specific circumstances. Empathy might allow me to recognize that I would have acted in the same manner as somebody else. Yet it does not epistemically sanction the claim that anybody of a particular type or anybody who is in that type of situation will act in this manner.

Hempel’s argument against empathy has certainly not gone unchallenged. Within the philosophy of history, Dray (1957), following Collingwood, has argued that empathy plays an epistemically irreducible role, since we explain actions in terms of an agent’s reasons. For him, such reason explanations do not appeal to empirical generalizations but to normative principles of actions outlining how a person should act in a particular situation. Similar arguments have been articulated by Jaegwon Kim (1984, 1998). Yet as Stueber (2006, chap. 5) argues such a response to Hempel would require us to implausibly conceive of reason explanations as being very different from ordinary causal explanations. It would imply that our notions of explanation and causation are ambiguous concepts. Reasons that cause agents to act in the physical world would be conceived of as causes in a very different sense than ordinary physical causes. Moreover, as Hempel himself suggests, appealing to normative principles explains at most why a person should have acted in a certain manner. It does not explain why he ultimately acted in that way. Consequently, Hempel’s objection against empathy retain their force as long as one maintains that reason explanations are a form of ordinary causal explanations and as long as one conceives of the epistemic justification of such explanations as implicitly appealing to some empirical generalizations (For Kim’s recent attempt to account for the explanatory character of action explanations by acknowledging the centrality of the first person perspective see also Kim 2010).

Despite these concessions to Hempel, Stueber suggests that empathy (specifically reenactive empathy) has to be acknowledged as playing a central role even in the context of justification. For him, folk psychological explanations have to be understood as being tied to the domain of rational agency. In contrast to explanations in terms of mere inner causes, folk psychological explanations retain their explanatory force only as long as agents’ beliefs and desires can also be understood as reasons for their actions. The epistemic justification of such folk psychological explanations implicitly relies on generalizations involving folk psychological notions such as belief and desire. Yet the existence of such generalizations alone does not establish specific beliefs and desires as reasons for a person’s actions. Elaborating on considerations by Heal (2003) and Collingwood (1946), Stueber suggests that recognizing beliefs and desires as reasons requires the interpreter to be sensitive to an agent’s other relevant beliefs and desires. Individual thoughts function as reasons for rational agency only relative to a specific framework of an agent’s thoughts that are relevant for consideration in a specific situation. Most plausibly—given our persistent inability to solve the frame problem—recognizing which of another agent’s thoughts are relevant in specific contexts requires the practical ability of reenacting another person’s thoughts in one’s own mind. Empathy’s central epistemic role has to be admitted, since beliefs and desires can be understood only in this manner as an agent’s reasons (See Stueber 2006, 2008, 2013. For a related discussion about the role of understanding in contemporary epistemology and philosophy of science see Grimm 2016 and Grimm, Baumberger, and Ammon 2017).

The discussion of empathy within psychology has been largely unaffected by the critical philosophical discussion of empathy as an epistemic means to know other minds or as the unique method of the human sciences. Rather, psychologists’ interest in empathy–related phenomena harks back to eighteenth century moral philosophy, particularly David Hume and Adam Smith (See also Wispe 1991). Here empathy, or what was then called sympathy, was regarded to play a central role in constituting human beings as social and moral creatures allowing us to emotionally connect to our human companions and care for their well-being. Throughout the early 20 th century, but particularly since the late 1940’s, empathy has, therefore, been an intensively studied topic of psychological research.

More broadly one can distinguish two psychological research traditions studying empathy–related phenomena; that is, the study of what is currently called empathic accuracy and the study of empathy as an emotional phenomenon in the encounter of others. The first area of study defines empathy primarily as a cognitive phenomenon and conceives of empathy in general terms as “the intellectual or imaginative apprehension of another’s condition or state of mind,” to use Hogan’s (1969) terminology. Within this area of research, one is primarily interested in determining the reliability and accuracy of our ability to perceive and recognize other persons’ enduring personality traits, attitudes and values, and occurrent mental states. One also investigates the various factors that influence empathic accuracy. One has, for example, been interested in determining whether empathic ability depends on gender, age, family background, intelligence, emotional stability, the nature of interpersonal relations, or whether it depends on specific motivations of the observer. (For a survey see Ickes 1993 and 2003; and Taft 1955). A more detailed account of the research on empathic accuracy and some of its earlier methodological difficulties can be found in the

Supplementary document on the Study of Cognitive Empathy and Empathic Accuracy .

Philosophically more influential has been the study of empathy defined primarily as an emotional or affective phenomenon, which psychologists in the middle of the 1950’s started to focus on. In this context, psychologists have also addressed issues of moral motivation that have been traditionally topics of intense discussions among moral philosophers. They were particularly interested in investigating (i) the development of various means for measuring empathy as a dispositional trait of adults and of children and as a situational response in specific situations, (ii) the factors on which empathic responses and dispositions depend, and (iii) the relation between empathy and pro-social behavior and moral development. Before discussing the psychological research on emotional empathy and its relevance for moral philosophy and moral psychology in the next section, it is vital to introduce important conceptual distinctions that one should keep in mind in evaluating the various empirical studies.

Anyone reading the emotional empathy literature has to be struck by the fact that empathy tended to be incredibly broadly defined in the beginning of this specific research tradition. Stotland, one of the earliest researcher who understood empathy exclusively as an emotional phenomenon, defined it as “an observer’s reacting emotionally because he perceives that another is experiencing or is about to experience an emotion” (1969, 272). According to Stotland’s definition very diverse emotional responses such as feeling envy, feeling annoyed, feeling distressed, being relieved about, feeling pity, or feeling what Germans call Schadenfreude (feeling joyful about the misfortune of another) have all to be counted as empathic reactions. Since the 1980’s however, psychologists have fine tuned their understanding of empathy conceptually and distinguished between different aspects of the emotional reaction to another person; thereby implicitly acknowledging the conceptual distinctions articulated by Max Scheler (1973) almost a century earlier. In this context, it is particularly useful to distinguish between the following reactive emotions that are differentiated in respect to whether or not such reactions are self or other oriented and whether they presuppose awareness of the distinction between self and others. (See also the survey in the Introduction to Eisenberg/Strayer 1987 and Batson 2009)

Emotional contagion: Emotional contagion occurs when people start feeling similar emotions caused merely by the association with other people. You start feeling joyful, because other people around you are joyful or you start feeling panicky because you are in a crowd of people feeling panic. Emotional contagion however does not require that one is aware of the fact that one experiences the emotions because other people experience them, rather one experiences them primarily as one’s own emotion (Scheler 1973, 22). A newborn infant’s reactive cry to the distress cry of another, which Hoffman takes as a “rudimentary precursor of empathic distress” (Hoffman 2000, 65), can probably be understood as a phenomenon of emotional contagion, since the infant is not able to properly distinguish between self and other.

Affective and proper Empathy: More narrowly and properly understood, empathy in the affective sense is the vicarious sharing of an affect. Authors however differ in how strictly they interpret the phrase of vicariously sharing an affect. For some, it requires that the empathizers and the persons they empathize with need to be in very similar affective states (Coplan 2011; de Vignemont and Singer 2006; Jacob 2011). For Hoffman, on the other hand, it is an emotional response requiring only “the involvement of psychological processes that make a person have feelings that are more congruent with another’s situation than with his own situation” (Hoffman 2000, 30). According to this definition, empathy does not necessarily require that the subject and target feel similar emotions (even though this is most often the case). Rather the definition also includes cases of feeling sad when seeing a child who plays joyfully but who does not know that it has been diagnosed with a serious illness (assuming that this is how the other person himself or herself would feel if he or she would fully understand his or her situation). In contrast to mere emotional contagion, genuine empathy presupposes the ability to differentiate between oneself and the other. It requires that one is minimally aware of the fact that one is having an emotional experience due to the perception of the other’s emotion, or more generally due to attending to his situation. In seeing a sad face of another and feeling sad oneself, such feeling of sadness should count as genuinely empathic only if one recognizes that in feeling sad one’s attention is still focused on the other and that it is not an appropriate reaction to aspects of one’s own life. Moreover, empathy outside the realm of a direct perceptual encounter involves some appreciation of the other person’s emotion as an appropriate response to his or her situation. To be happy or unhappy because one’s child is happy or sad should not count necessarily as an empathic emotion. It cannot count as a vicarious emotional response if it is due to the perception of the outside world from the perspective of the observer and her desire that her children should be happy. My happiness about my child being happy would therefore not be an emotional state that is more congruent to his situation. Rather, it is an emotional response appropriate to my own perspective on the world. In order for my happiness or unhappiness to be genuinely empathic it has to be happiness or unhappiness about what makes the other person happy. Accordingly, if I share another person’s emotion vicariously I do not merely have to be in an affective state with a similar phenomenal quality. Rather my affective state has to be directed toward the same intentional object. (See Sober and Wilson 1998, 231–237 and Maibom 2007. For a critical discussion of how and whether such vicarious sharing is possible see also Deonna 2007 and Matravers 2018). It should be noted, however, that some authors conceive of proper empathy more broadly as not merely being concerned with the vicarious reenactment of affective states but more comprehensively as including non-affective states such as beliefs and desires. This is especially true if they are influenced by the discussion of of empathy as an epistemic means such as Goldman (2011) and Stueber (2006). However, already Adam Smith (1853) constitutes a good example for such broad understanding of proper empathy. Finally, others suggest that it is best to distinguish between affective sharing and perspective taking (Decety and Cowell 2015).

Sympathy: In contrast to affective empathy, sympathy—or what some authors also refer to as empathic concern—is not an emotion that is congruent with the other’s emotion or situation such as feeling the sadness of the other person’s grieving for the death of his father. Rather, sympathy is seen as an emotion sui generis that has the other’s negative emotion or situation as its object from the perspective of somebody who cares for the other person’s well being (Darwall 1998). In this sense, sympathy consists of “feeling sorrow or concern for the distressed or needy other,” a feeling for the other out of a “heightened awareness of the suffering of another person as something that needs to be alleviated.” (Eisenberg 2000a, 678; Wispe 1986, 318; and Wispe 1991).

Whereas it is quite plausible to assume that empathy—that is, empathy with negative emotions of another or what Hoffman (2000) calls “veridical empathic distress”—under certain conditions (and when certain developmental markers are achieved) can give rise to sympathy, it should be stressed that the relation between affective empathy and sympathy is a contingent one; the understanding of which requires further empirical research. First, sympathy does not necessarily require feeling any kind of congruent emotions on part of the observer, a detached recognition or representation that the other is in need or suffers might be sufficient. (See Scheler 1973 and Nichols 2004). Second, empathy or empathic distress might not at all lead to sympathy. People in the helping professions, who are so accustomed to the misery of others, suffer at times from compassion fatigue. It is also possible to experience empathic overarousal because one is emotionally so overwhelmed by one’s empathic feelings that one is unable to be concerned with the suffering of the other (Hoffman 2000, chap. 8). In the later case, one’s empathic feeling are transformed or give rise to mere personal distress, a reactive emotional phenomenon that needs to be distinguished from emotional contagion, empathy, and sympathy.

Personal Distress: Personal distress in the context of empathy research is understood as a reactive emotion in response to the perception/recognition of another’s negative emotion or situation. Yet, while personal distress is other-caused like sympathy, it is, in contrast to sympathy, primarily self-oriented . In this case, another person’s distress does not make me feel bad for him or her, it just makes me feel bad, or “alarmed, grieved, upset, worried, disturbed, perturbed, distressed,and troubled;” to use the list of adjectives that according to Batson’s research indicates personal distress (Batson et al. 1987 and Batson 1991). And, in contrast to empathic emotions as defined above, my personal distress is not any more congruent with the emotion or situation of another. Rather it wholly defines my own outlook onto the world.

While it is conceptually necessary to differentiate between these various emotional responses, it has to be admitted that it is empirically not very easy to discriminate between them, since they tend to occur together. Think or imagine yourself attending the funeral of the child of a friend or good acquaintance. This is probably one reason why early researchers tended not to distinguish between the above aspects in their study of empathy related phenomena. Yet since the above distinctions refer to very different psychological mechanisms, it is absolutely central to distinguish between them when empirically assessing the impact and contribution of empathy to an agent’s pro-social motivation and behavior. Given the ambiguity of the empathy concept within psychology—particularly in the earlier literature—in evaluating and comparing different empirical empathy studies, it is always crucial to keep in mind how empathy has been defined and measured within the context of these studies. For a more extensive discussion of the methods used by psychologists to measure empathy see the

Supplementary document on Measuring Empathy .

5. Empathy, Moral Philosophy, and Moral Psychology

Moral philosophers have always been concerned with moral psychology and with articulating an agent’s motivational structure in order to explicate the importance of morality for a human life. After all, moral judgments supposedly make demands on an agent’s will and are supposed to provide us with reasons and motivations for acting in a certain manner. Yet moral judgments, at least in the manner in which we conceive of them in modern times, are also regarded to be based on normative standards that, in contrast to mere conventional norms, have universal scope and are valid independent of the features of specific social practices that agents are embedded in. One only needs to think of statements such as “cruelty to innocent children or slavery is morally wrong,” which we view as applying also to social practices where the attitude of its population seem to condone such actions. Moral judgements thus seem to address us from the perspective of the moral stance where we leave behind the perspective of self-love and do not conceive of each other either as friends or foes (see Hume 1987, 75) or as belonging to the in–group or out–group, but where we view each other all to be equal part of a moral community. Finally, and relatedly, in order to view morality as something that is possible for human beings we also seem to require that our motivations based on or associated with moral reasons have a self-less character. Given to charity for merely selfish reasons, for example, seems to clearly diminish its moral worth and implicitly deny the universal character of a moral demand. Philosophically explicating the importance of morality for human life then has to do the following: It has to explain how it is that we humans as a matter of fact do care about morality thusly conceived, it has to address the philosophically even more pertinent question of why it is that we should care about morality or why it is that we should regard judgments issued from the perspective of the moral stance to have normative authority over us; and it has to allow us to understand how it is that we can act self-lessly in a manner that correspond to the demands made on us from the moral stance. Answering all of these questions however necessitates at one point to explain how our moral interests are related to our psychological constitution as human beings and how moral demands can be understood as being appropriately addressed to agents who are psychologically structured in that manner.

Prima facie, the difficulty of this enterprise consists in squaring a realistic account of human psychology with the universal scope and intersubjective validity of moral judgments, since human motivation and psychological mechanisms seem to be always situational, local, and of rather limited scope. Moreover, as evolutionary psychologists tell us in–group bias seems to be a universal trait of human psychology. One of the most promising attempts to solve this problem is certainly due to the tradition of eighteenth century moral philosophy associated with the names of David Hume and Adam Smith who tried to address all of the above philosophical desiderata by pointing to the central role that our empathic and sympathetic capacities have for constituting us as social and moral agents and for providing us with the psychological capacities to make and to respond to moral judgments. While philosophers in the Kantian tradition, who favor reason over sentiments, have generally been skeptical about this proposal, more recently the claim that empathy is central for morality and a flourishing human life has again been the topic of an intense and controversial debate. On the one hand, empathy has been hailed by researchers from a wide range of disciplines and also by some public figures, President Obama most prominently among them. Slote (2010) champions empathy as the sole foundation of moral judgment, de Waal (2006) conceives of it as the unique evolutionary building block of morality, Rifkin (2009) regards it even as a force whose cultivation has unique revolutionary powers to transform a world in crisis, and Baron-Cohen (2011, 194) views it as a “universal solvent” in that “any problem immersed in empathy becomes soluble.” On the other hand, such empathy enthusiasm has encountered penetrating criticism by Prinz (2011 a,b) and Bloom (2016), who emphasize its dark side, that is, its tendency to fall prey to so–called “here and now” biases. The following subsections will address these issues by surveying the relevant empirical research on the question whether empathy motivates us in a self-less manner, the question of whether empathy is inherently biased and partial to the in-group, and it will discuss how we might think of the normative character of moral judgments in light of our empathic capacities.(For a survey of other relevant issues from social psychology, specifically social neuroscience, consult also Decety and Lamm 2006; Decety and Ickes 2009, and Decety 20012. For a discussion of the importance empathy for medical practice see Halpern 2001)

In a series of ingeniously designed experiments, Batson has accumulated evidence for what he calls the empathy-altruism thesis. In arguing for this thesis, Batson conceives of empathy as empathic concern or what others would call sympathy. More specifically, he characterized it in terms of feelings of being sympathetic, moved by, being compassionate, tender, warm and soft-hearted towards the other’s plight (Batson et al. 1987, 26) The task of his experiments consists in showing that empathy/sympathy does indeed lead to genuinely altruistic motivation, where the welfare of the other is the ultimate goal of my helping behavior, rather than to helping behavior because of predominantly egoistic motivations. According to the egoistic interpretation of empathy–related phenomena, empathizing with another person in need is associated with a negative feeling or can lead to a heightened awareness of the negative consequences of not helping; such as feelings of guilt, shame, or social sanctions. Alternatively, it can lead to an enhanced recognition of the positive consequences of helping behavior such as social rewards or good feelings. Empathy according to this interpretation induces us to help through mediation of purely egoistic motivations. We help others only because we recognize helping behavior as a means to egoistic ends. It allows us to reduce our negative feelings (aversive arousal reduction hypothesis), to avoid “punishment,” or to gain specific internal or external “rewards” (empathy-specific punishment and empathy-specific reward hypotheses).