Home — Essay Samples — Environment — Human Impact — Endangered Species

Essays on Endangered Species

Endangered species essay topics and outline examples, essay title 1: vanishing wonders: the plight of endangered species and conservation efforts.

Thesis Statement: This essay explores the critical issue of endangered species, delving into the causes of endangerment, the ecological significance of these species, and the conservation strategies aimed at preserving them for future generations.

- Introduction

- Understanding Endangered Species: Definitions and Criteria

- Causes of Endangerment: Habitat Loss, Climate Change, Poaching, and Pollution

- Ecological Significance: The Role of Endangered Species in Ecosystems

- Conservation Strategies: Protected Areas, Breeding Programs, and Legal Protections

- Success Stories: Examples of Species Recovery and Reintroduction

- Ongoing Challenges: Balancing Conservation with Human Needs

- Conclusion: The Urgent Need for Global Action in Protecting Endangered Species

Essay Title 2: Beyond the Numbers: The Ethical and Moral Imperatives of Endangered Species Preservation

Thesis Statement: This essay examines the ethical dimensions of endangered species preservation, addressing questions of human responsibility, intrinsic value, and the moral imperative to protect and restore these species.

- The Ethical Dilemma: Balancing Human Needs and Species Preservation

- Intrinsic Value: Recognizing the Inherent Worth of All Species

- Interconnectedness: Understanding the Ripple Effects of Species Loss

- Human Responsibility: The Moral Imperative to Protect Endangered Species

- Conservation Ethics: Ethical Frameworks and Philosophical Perspectives

- Legislation and International Agreements: Legal Approaches to Ethical Conservation

- Conclusion: Embracing Our Role as Stewards of Biodiversity

Essay Title 3: The Economic Value of Biodiversity: Endangered Species and Sustainable Development

Thesis Statement: This essay explores the economic aspects of endangered species conservation, highlighting the potential economic benefits of preserving biodiversity, sustainable ecotourism, and the long-term economic consequences of species loss.

- Economic Importance of Biodiversity: Ecosystem Services and Human Well-being

- Sustainable Ecotourism: How Endangered Species Can Drive Local Economies

- Case Studies: Success Stories of Economic Benefits from Species Conservation

- The Costs of Inaction: Economic Consequences of Species Extinction

- Corporate Responsibility: Businesses and Conservation Partnerships

- Balancing Economic Growth with Conservation: The Path to Sustainable Development

- Conclusion: The Interplay Between Biodiversity, Economics, and a Sustainable Future

Giant Pandas Ailuropoda

Circle of life: why should we protect endangered species, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

Endangered Species: The African Elephant

Endangered species: the factors and the ways to prevent, loss of habitat as one of the main factors of the increase in endangered species, endangered animals: the causes and how to protect, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Endangered Species in Vietnam: South China Tiger and Asian Elephant

Funding and support for people responsible for protecting endangered species, endangered animals and the acts to protect them, keystone species and the importance of raising endangered species awareness, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

De-extinction Can Help to Protect Endangered Species

Protection of endangered species can help us to survive, the way zoos helps to protect endangered species, ways of protection endangered species, sharks demand protection just like endangered species, the reasons why the koala species is endangered, the issue of philippine eagle endangerment, the issue of conserving endangered animals in the jungles of southeast asia, primates research project: the bushmeat crisis, the negative impact of the food culture on the environment and jani actman article that fish on your dinner plate may be an endangered species, nesting and population ecology of western chimpanzee in bia conservation area, human impact on red panda populations , the impact of climate change on the antarctic region, the ethics of bengal tigers, poaching and the illegal trade.

Endangered species are living organisms that face a high risk of extinction in the near future. They are characterized by dwindling population numbers and a significant decline in their natural habitats. These species are vulnerable to various factors, including habitat destruction, pollution, climate change, overexploitation, and invasive species, which disrupt their ecological balance and threaten their survival.

The early stages of human civilization witnessed a relatively harmonious coexistence with the natural world. Indigenous cultures across the globe held deep reverence for the interconnectedness of all living beings, fostering a sense of stewardship and respect for the environment. Nevertheless, with the rise of industrialization and modernization, the exploitation of natural resources escalated at an unprecedented pace. The late 19th and early 20th centuries marked a turning point, as rapid urbanization, deforestation, pollution, and overhunting posed significant threats to numerous species. The dawn of globalization further accelerated these challenges, as international trade in exotic species intensified and habitats faced relentless encroachment. In response to this growing concern, conservation movements emerged worldwide. Influential figures such as John Muir, Rachel Carson, and Aldo Leopold championed the cause of environmental preservation, raising awareness about the fragility of ecosystems and the need for proactive measures. International conventions and treaties, such as the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), were established to regulate and monitor the trade of endangered species across borders. As our understanding of ecological dynamics deepened, scientific advancements and conservation efforts gained momentum. Endangered species recovery programs, habitat restoration initiatives, and the establishment of protected areas have all played a vital role in safeguarding vulnerable populations. However, the struggle to protect endangered species continues in the face of ongoing challenges. Climate change, habitat destruction, poaching, and illegal wildlife trade persist as formidable threats. Efforts to conserve endangered species require a multi-faceted approach, encompassing scientific research, policy development, sustainable practices, and international collaboration.

Leonardo DiCaprio: An acclaimed actor and environmental activist, DiCaprio has been an outspoken advocate for wildlife conservation. Through the Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation, he has supported various initiatives aimed at protecting endangered species and their habitats. Sigourney Weaver: Besides her notable acting career, Sigourney Weaver has been a passionate environmental activist. She has advocated for the protection of endangered species, particularly in her role as an honorary co-chair of the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund. Prince William: The Duke of Cambridge, Prince William, has shown a deep commitment to wildlife conservation. He has actively supported initiatives such as United for Wildlife, which aims to combat the illegal wildlife trade and protect endangered species. Edward Norton: Actor and environmental activist Edward Norton has been actively involved in various conservation efforts. He co-founded the Conservation International's Marine Program and has been vocal about the need to protect endangered species and their habitats.

Amur Leopard (Panthera pardus orientalis) Sumatran Orangutan (Pongo abelii) Javan Rhino (Rhinoceros sondaicus) Vaquita (Phocoena sinus) Cross River Gorilla (Gorilla gorilla diehli) Hawksbill Turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) Yangtze River Dolphin (Lipotes vexillifer) Philippine Eagle (Pithecophaga jefferyi) Sumatran Tiger (Panthera tigris sumatrae) African Elephant (Loxodonta africana)

1. Habitat Loss and Fragmentation 2. Climate Change 3. Pollution 4. Overexploitation and Illegal Wildlife Trade 5. Invasive Species 6. Disease and Pathogens 7. Lack of Conservation Efforts and Awareness 8. Genetic Issues 9. Natural Factors

The majority of the public recognizes the significance of conserving endangered species. Many people believe that it is our moral obligation to protect and preserve the Earth's diverse wildlife. They understand that losing species not only disrupts ecosystems but also deprives future generations of the natural beauty and ecological services they provide. Some individuals view endangered species conservation through an economic lens. They understand that wildlife and ecosystems contribute to tourism, provide ecosystem services like clean water and air, and support local economies. These economic arguments often align with conservation efforts, highlighting the potential benefits of protecting endangered species. Additionally, public opinion on endangered species is often shaped by awareness campaigns, education initiatives, and media coverage. Increased access to information about the threats faced by endangered species and the consequences of their decline has resulted in a greater understanding and concern among the public. Many people support the implementation and enforcement of laws and regulations aimed at protecting endangered species. They believe that legal frameworks are essential for ensuring the survival of vulnerable species and holding individuals and industries accountable for actions that harm wildlife. Moreover, individuals increasingly feel a sense of personal responsibility in addressing the issue of endangered species. This includes making conscious choices about consumption, supporting sustainable practices, and engaging in activities that contribute to conservation efforts, such as volunteering or donating to wildlife organizations. Public opinion can vary when it comes to instances where the protection of endangered species conflicts with human interests, such as land use, agriculture, or development projects. These situations can lead to debates and differing perspectives on how to balance conservation needs with other societal needs.

"Silent Spring" by Rachel Carson: Published in 1962, this influential book is credited with launching the modern environmental movement. Carson's seminal work highlighted the devastating impacts of pesticides, including their effects on wildlife and the environment. It drew attention to the need for conservation and sparked widespread concern for endangered species. "Gorillas in the Mist" by Dian Fossey: Fossey's book, published in 1983, chronicled her experiences studying and protecting mountain gorillas in Rwanda. It shed light on the challenges faced by these endangered primates and brought their conservation needs to the forefront of public consciousness. "March of the Penguins" (2005): This acclaimed documentary film depicted the annual journey of emperor penguins in Antarctica. By showcasing the hardships and perils these penguins face, the film garnered widespread attention and empathy for these remarkable creatures, raising awareness about their vulnerability and the impacts of climate change. "The Cove" (2009): This documentary exposed the brutal practice of dolphin hunting in Taiji, Japan. It not only brought attention to the mistreatment of dolphins but also highlighted the interconnectedness of species and the urgent need for their protection. "Racing Extinction" (2015): This documentary film by the Oceanic Preservation Society addressed the issue of mass species extinction and the human-driven factors contributing to it. It aimed to inspire viewers to take action and make positive changes to protect endangered species and their habitats.

1. It is estimated that around 26,000 species are currently threatened with extinction, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). 2. The illegal wildlife trade is the fourth largest illegal trade globally, following drugs, counterfeiting, and human trafficking. It is a significant contributor to species endangerment. 3. The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) reports that since 1970, global wildlife populations have declined by an average of 68%. 4. Habitat loss is the primary cause of species endangerment, with deforestation alone accounting for the loss of around 18.7 million acres of forest annually. 5. The poaching crisis has pushed some iconic species to the brink of extinction. For example, it is estimated that only about 3,900 tigers remain in the wild. 6. The Hawaiian Islands are considered the endangered species capital of the world, with more than 500 endangered or threatened species due to habitat loss and invasive species. 7. Coral reefs, one of the most diverse ecosystems on the planet, are under significant threat. It is estimated that 75% of the world's coral reefs are currently threatened, primarily due to climate change, pollution, and overfishing. 8. The illegal pet trade is a significant threat to many species. It is estimated that for every live animal captured for the pet trade, several die during capture or transport. 9. The IUCN Red List, a comprehensive inventory of the conservation status of species, currently includes more than 38,000 species, with approximately 28% of them classified as threatened with extinction.

The topic of endangered species holds immense importance for writing an essay due to several compelling reasons. Firstly, endangered species represent a vital component of the Earth's biodiversity, playing crucial roles in maintaining ecosystem balance and functioning. Exploring this topic allows us to understand the interconnectedness of species and their habitats, emphasizing the intricate web of life on our planet. Secondly, the issue of endangered species is a direct reflection of human impacts on the environment. It brings attention to the consequences of habitat destruction, climate change, pollution, and unsustainable practices. By studying this topic, we can delve into the root causes of species endangerment and contemplate the ethical and moral dimensions of our responsibility towards other living beings. Moreover, the plight of endangered species evokes strong emotional responses, prompting discussions on the intrinsic value of nature and our duty to conserve it for future generations. Writing about endangered species enables us to raise awareness, foster empathy, and advocate for sustainable practices and conservation initiatives.

1. Dudley, N., & Stolton, S. (Eds.). (2010). Arguments for protected areas: Multiple benefits for conservation and use. Earthscan. 2. Fearn, E., & Butler, C. D. (Eds.). (2019). Routledge handbook of eco-anxiety. Routledge. 3. Groombridge, B., & Jenkins, M. D. (2002). World atlas of biodiversity: Earth's living resources in the 21st century. University of California Press. 4. Hoekstra, J. M., Boucher, T. M., Ricketts, T. H., & Roberts, C. (2005). Confronting a biome crisis: Global disparities of habitat loss and protection. Ecology Letters, 8(1), 23-29. 5. Kiesecker, J. M., & Copeland, H. E. (Eds.). (2018). The biogeography of endangered species: Patterns and applications. Island Press. 6. Laurance, W. F., Sayer, J., & Cassman, K. G. (2014). Agricultural expansion and its impacts on tropical nature. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 29(2), 107-116. 7. Meffe, G. K., & Carroll, C. R. (Eds.). (1997). Principles of conservation biology. Sinauer Associates. 8. Primack, R. B. (2014). Essentials of conservation biology. Sinauer Associates. 9. Soulé, M. E., & Terborgh, J. (Eds.). (1999). Continental conservation: Scientific foundations of regional reserve networks. Island Press. 10. Wilson, E. O. (2016). Half-earth: Our planet's fight for life. Liveright Publishing.

Relevant topics

- Fast Fashion

- Water Pollution

- Deforestation

- Air Pollution

- Plastic Bags

- Nuclear Energy

- Global Warming

- Ocean Pollution

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

November 1, 2023

20 min read

Can We Save Every Species from Extinction?

The Endangered Species Act requires that every U.S. plant and animal be saved from extinction, but after 50 years, we have to do much more to prevent a biodiversity crisis

By Robert Kunzig

Snail Darter Percina tanasi. Listed as Endangered: 1975. Status: Delisted in 2022.

© Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark

A Bald Eagle disappeared into the trees on the far bank of the Tennessee River just as the two researchers at the bow of our modest motorboat began hauling in the trawl net. Eagles have rebounded so well that it's unusual not to see one here these days, Warren Stiles of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service told me as the net got closer. On an almost cloudless spring morning in the 50th year of the Endangered Species Act, only a third of a mile downstream from the Tennessee Valley Authority's big Nickajack Dam, we were searching for one of the ESA's more notorious beneficiaries: the Snail Darter. A few months earlier Stiles and the FWS had decided that, like the Bald Eagle, the little fish no longer belonged on the ESA's endangered species list. We were hoping to catch the first nonendangered specimen.

Dave Matthews, a TVA biologist, helped Stiles empty the trawl. Bits of wood and rock spilled onto the deck, along with a Common Logperch maybe six inches long. So did an even smaller fish; a hair over two inches, it had alternating vertical bands of dark and light brown, each flecked with the other color, a pattern that would have made it hard to see against the gravelly river bottom. It was a Snail Darter in its second year, Matthews said, not yet full-grown.

Everybody loves a Bald Eagle. There is much less consensus about the Snail Darter. Yet it epitomizes the main controversy still swirling around the ESA, signed into law on December 28, 1973, by President Richard Nixon: Can we save all the obscure species of this world, and should we even try, if they get in the way of human imperatives? The TVA didn't think so in the 1970s, when the plight of the Snail Darter—an early entry on the endangered species list—temporarily stopped the agency from completing a huge dam. When the U.S. attorney general argued the TVA's case before the Supreme Court with the aim of sidestepping the law, he waved a jar that held a dead, preserved Snail Darter in front of the nine judges in black robes, seeking to convey its insignificance.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Now I was looking at a living specimen. It darted around the bottom of a white bucket, bonking its nose against the side and delicately fluttering the translucent fins that swept back toward its tail.

“It's kind of cute,” I said.

Matthews laughed and slapped me on the shoulder. “I like this guy!” he said. “Most people are like, ‘Really? That's it?’ ” He took a picture of the fish and clipped a sliver off its tail fin for DNA analysis but left it otherwise unharmed. Then he had me pour it back into the river. The next trawl, a few miles downstream, brought up seven more specimens.

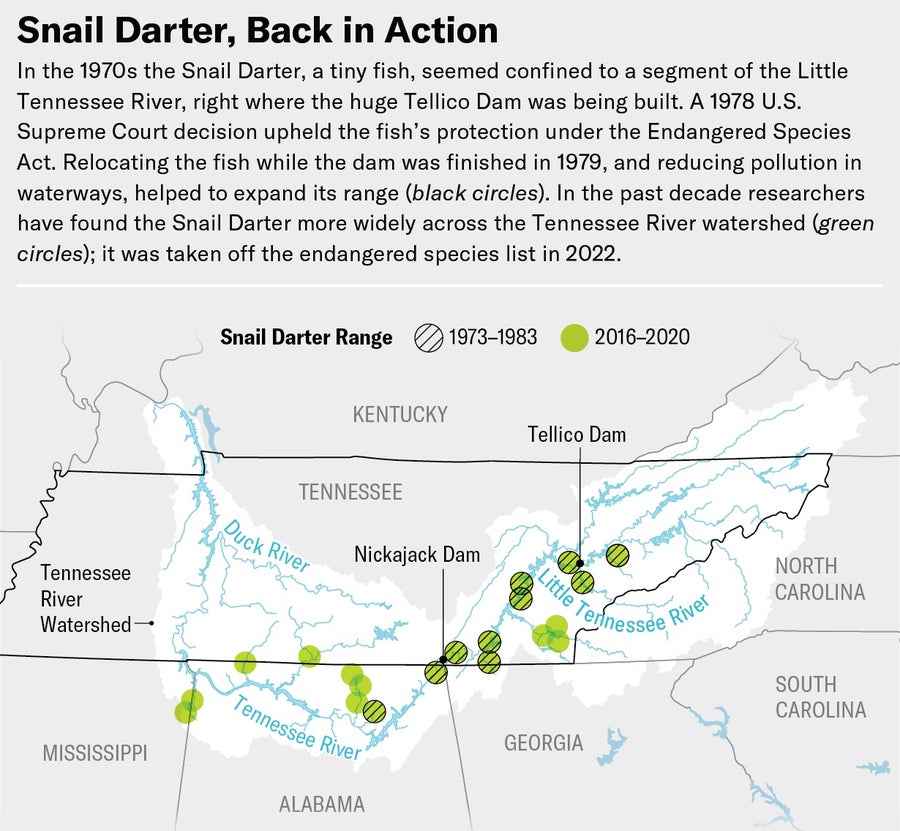

In the late 1970s the Snail Darter seemed confined to a single stretch of a single tributary of the Tennessee River, the Little Tennessee, and to be doomed by the TVA's ill-considered Tellico Dam, which was being built on the tributary. The first step on its twisting path to recovery came in 1978, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled, surprisingly, that the ESA gave the darter priority even over an almost finished dam. “It was when the government stood up and said, ‘Every species matters, and we meant it when we said we're going to protect every species under the Endangered Species Act,’” says Tierra Curry, a senior scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity.

Bald Eagle Haliaeetus leucocephalus. Listed as Endangered: 1967. Status: Delisted in 2007. Credit: © Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark

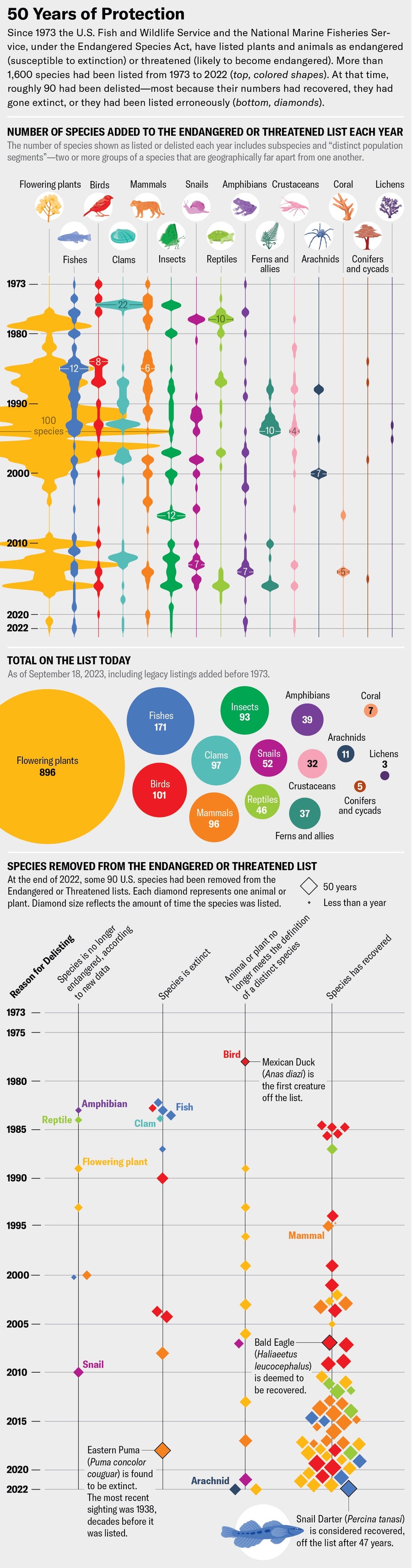

Today the Snail Darter can be found along 400 miles of the river's main stem and multiple tributaries. ESA enforcement has saved dozens of other species from extinction. Bald Eagles, American Alligators and Peregrine Falcons are just a few of the roughly 60 species that had recovered enough to be “delisted” by late 2023.

And yet the U.S., like the planet as a whole, faces a growing biodiversity crisis. Less than 6 percent of the animals and plants ever placed on the list have been delisted; many of the rest have made scant progress toward recovery. What's more, the list is far from complete: roughly a third of all vertebrates and vascular plants in the U.S. are vulnerable to extinction, says Bruce Stein, chief scientist at the National Wildlife Federation. Populations are falling even for species that aren't yet in danger. “There are a third fewer birds flying around now than in the 1970s,” Stein says. We're much less likely to see a White-throated Sparrow or a Red-winged Blackbird, for example, even though neither species is yet endangered.

The U.S. is far emptier of wildlife sights and sounds than it was 50 years ago, primarily because habitat—forests, grasslands, rivers—has been relentlessly appropriated for human purposes. The ESA was never designed to stop that trend, any more than it is equipped to deal with the next massive threat to wildlife: climate change. Nevertheless, its many proponents say, it is a powerful, foresightful law that we could implement more wisely and effectively, perhaps especially to foster stewardship among private landowners. And modest new measures, such as the Recovering America's Wildlife Act—a bill with bipartisan support—could further protect flora and fauna.

That is, if special interests don't flout the law. After the 1978 Supreme Court decision, Congress passed a special exemption to the ESA allowing the TVA to complete the Tellico Dam. The Snail Darter managed to survive because the TVA transplanted some of the fish from the Little Tennessee, because remnant populations turned up elsewhere in the Tennessee Valley, and because local rivers and streams slowly became less polluted following the 1972 Clean Water Act, which helped fish rebound.

Under pressure from people enforcing the ESA, the TVA also changed the way it managed its dams throughout the valley. It started aerating the depths of its reservoirs, in some places by injecting oxygen. It began releasing water from the dams more regularly to maintain a minimum flow that sweeps silt off the river bottom, exposing the clean gravel that Snail Darters need to lay their eggs and feed on snails. The river system “is acting more like a real river,” Matthews says. Basically, the TVA started considering the needs of wildlife, which is really what the ESA requires. “The Endangered Species Act works,” Matthews says. “With just a little bit of help, [wildlife] can recover.”

The trouble is that many animals and plants aren't getting that help—because government resources are too limited, because private landowners are alienated by the ESA instead of engaged with it, and because as a nation the U.S. has never fully committed to the ESA's essence. Instead, for half a century, the law has been one more thing that polarizes people's thinking.

I t may seem impossible today to imagine the political consensus that prevailed on environmental matters in 1973. The U.S. Senate approved the ESA unanimously, and the House passed it by a vote of 390 to 12. “Some people have referred to it as almost a statement of religion coming out of the Congress,” says Gary Frazer, who as assistant director for ecological services at the FWS has been overseeing the act's implementation for nearly 25 years.

Gopher Tortoise Gopherus polyphemus . Listed as Threatened: 1987. Status: Still threatened. Credit: ©Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark

But loss of faith began five years later with the Snail Darter case. Congresspeople who had been thinking of eagles, bears and Whooping Cranes when they passed the ESA, and had not fully appreciated the reach of the sweeping language they had approved, were disabused by the Supreme Court. It found that the legislation had created, “wisely or not ... an absolute duty to preserve all endangered species,” Chief Justice Warren E. Burger said after the Snail Darter case concluded. Even a recently discovered tiny fish had to be saved, “whatever the cost,” he wrote in the decision.

Was that wise? For both environmentalists such as Curry and many nonenvironmentalists, the answer has always been absolutely. The ESA “is the basic Bill of Rights for species other than ourselves,” says National Geographic photographer Joel Sartore, who is building a “photo ark” of every animal visible to the naked eye as a record against extinction. (He has taken studio portraits of 15,000 species so far.) But to critics, the Snail Darter decision always defied common sense. They thought it was “crazy,” says Michael Bean, a leading ESA expert, now retired from the Environmental Defense Fund. “That dichotomy of view has remained with us for the past 45 years.”

According to veteran Washington, D.C., environmental attorney Lowell E. Baier, author of a new history called The Codex of the Endangered Species Act, both the act itself and its early implementation reflected a top-down, federal “command-and-control mentality” that still breeds resentment. FWS field agents in the early days often saw themselves as combat biologists enforcing the act's prohibitions. After the Northern Spotted Owl's listing got tangled up in a bitter 1990s conflict over logging of old-growth forests in the Pacific Northwest, the FWS became more flexible in working out arrangements. “But the dark mythology of the first 20 years continues in the minds of much of America,” Baier says.

Credit: June Minju Kim ( map ); Source: David Matthews, Tennessee Valley Authority ( reference )

The law can impose real burdens on landowners. Before doing anything that might “harass” or “harm” an endangered species, including modifying its habitat, they need to get a permit from the FWS and present a “habitat conservation plan.” Prosecutions aren't common, because evidence can be elusive, but what Bean calls “the cloud of uncertainty” surrounding what landowners can and cannot do can be distressing.

Requirements the ESA places on federal agencies such as the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management—or on the TVA—can have large economic impacts. Section 7 of the act prohibits agencies from taking, permitting or funding any action that is likely to “jeopardize the continued existence” of a listed species. If jeopardy seems possible, the agency must consult with the FWS first (or the National Marine Fisheries Service for marine species) and seek alternative plans.

“When people talk about how the ESA stops projects, they've been talking about section 7,” says conservation biologist Jacob Malcom. The Northern Spotted Owl is a strong example: an economic analysis suggests the logging restrictions eliminated thousands of timber-industry jobs, fueling conservative arguments that the ESA harms humans and economic growth.

In recent decades, however, that view has been based “on anecdote, not evidence,” Malcom claims. At Defenders of Wildlife, where he worked until 2022 (he's now at the U.S. Department of the Interior), he and his colleagues analyzed 88,290 consultations between the FWS and other agencies from 2008 to 2015. “Zero projects were stopped,” Malcom says. His group also found that federal agencies were only rarely taking the active measures to recover a species that section 7 requires—like what the TVA did for the Snail Darter. For many listed species, the FWS does not even have recovery plans.

Endangered species also might not recover because “most species are not receiving protection until they have reached dangerously low population sizes,” according to a 2022 study by Erich K. Eberhard of Columbia University and his colleagues. Most listings occur only after the FWS has been petitioned or sued by an environmental group—often the Center for Biological Diversity, which claims credit for 742 listings. Years may go by between petition and listing, during which time the species' population dwindles. Noah Greenwald, the center's endangered species director, thinks the FWS avoids listings to avoid controversy—that it has internalized opposition to the ESA.

He and other experts also say that work regarding endangered species is drastically underfunded. As more species are listed, the funding per species declines. “Congress hasn't come to grips with the biodiversity crisis,” says Baier, who lobbies lawmakers regularly. “When you talk to them about biodiversity, their eyes glaze over.” Just this year federal lawmakers enacted a special provision exempting the Mountain Valley Pipeline from the ESA and other challenges, much as Congress had exempted the Tellico Dam. Environmentalists say the gas pipeline, running from West Virginia to Virginia, threatens the Candy Darter, a colorful small fish. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 provided a rare bit of good news: it granted the FWS $62.5 million to hire more biologists to prepare recovery plans.

The ESA is often likened to an emergency room for species: overcrowded and understaffed, it has somehow managed to keep patients alive, but it doesn't do much more. The law contains no mandate to restore ecosystems to health even though it recognizes such work as essential for thriving wildlife. “Its goal is to make things better, but its tools are designed to keep things from getting worse,” Bean says. Its ability to do even that will be severely tested in coming decades by threats it was never designed to confront.

T he ESA requires a species to be listed as “threatened” if it might be in danger of extinction in the “foreseeable future.” The foreseeable future will be warmer. Rising average temperatures are a problem, but higher heat extremes are a bigger threat, according to a 2020 study.

Scientists have named climate change as the main cause of only a few extinctions worldwide. But experts expect that number to surge. Climate change has been “a factor in almost every species we've listed in at least the past 15 years,” Frazer says. Yet scientists struggle to forecast whether individual species can “persist in place or shift in space”—as Stein and his co-authors put it in a recent paper—or will be unable to adapt at all and will go extinct. On June 30 the FWS issued a new rule that will make it easier to move species outside their historical range—a practice it once forbade except in extreme circumstances.

Credit: June Minju Kim ( graphic ); Brown Bird Design ( illustrations ); Sources: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Environmental Conservation Online System; U.S. Federal Endangered and Threatened Species by Calendar Year https://ecos.fws.gov/ecp/report/species-listings-by-year-totals ( annual data through 2022 ); Listed Species Summary (Boxscore) https://ecos.fws.gov/ecp/report/boxscore ( cumulative data up to September 18, 2023, and annual data for coral ); Delisted Species https://ecos.fws.gov/ecp/report/species-delisted ( delisted data through 2022 )

Eventually, though, “climate change is going to swamp the ESA,” says J. B. Ruhl, a law professor at Vanderbilt University, who has been writing about the problem for decades. “As more and more species are threatened, I don't know what the agency does with that.” To offer a practical answer, in a 2008 paper he urged the FWS to aggressively identify the species most at risk and not waste resources on ones that seem sure to expire.

Yet when I asked Frazer which urgent issues were commanding his attention right now, his first thought wasn't climate; it was renewable energy. “Renewable energy is going to leave a big footprint on the planet and on our country,” he says, some of it threatening plants and animals if not implemented well. “The Inflation Reduction Act is going to lead to an explosion of more wind and solar across the landscape.

Long before President Joe Biden signed that landmark law, conflicts were proliferating: Desert Tortoise versus solar farms in the Mojave Desert, Golden Eagles versus wind farms in Wyoming, Tiehm's Buckwheat (a little desert flower) versus lithium mining in Nevada. The mine case is a close parallel to that of Snail Darters versus the Tellico Dam. The flower, listed as endangered just last year, grows on only a few acres of mountainside in western Nevada, right where a mining company wants to extract lithium. The Center for Biological Diversity has led the fight to save it. Elsewhere in Nevada people have used the ESA to stop, for the moment, a proposed geothermal plant that might threaten the two-inch Dixie Valley Toad, discovered in 2017 and also declared endangered last year.

Does an absolute duty to preserve all endangered species make sense in such places? In a recent essay entitled “A Time for Triage,” Columbia law professor Michael Gerrard argues that “the environmental community has trade-off denial. We don't recognize that it's too late to preserve everything we consider precious.” In his view, given the urgency of building the infrastructure to fight climate change, we need to be willing to let a species go after we've done our best to save it. Environmental lawyers adept at challenging fossil-fuel projects, using the ESA and other statutes, should consider holding their fire against renewable installations. “Just because you have bullets doesn't mean you shoot them in every direction,” Gerrard says. “You pick your targets.” In the long run, he and others argue, climate change poses a bigger threat to wildlife than wind turbines and solar farms do.

For now habitat loss remains the overwhelming threat. What's truly needed to preserve the U.S.'s wondrous biodiversity, both Stein and Ruhl say, is a national network of conserved ecosystems. That won't be built with our present politics. But two more practical initiatives might help.

The first is the Recovering America's Wildlife Act, which narrowly missed passage in 2022 and has been reintroduced this year. It builds on the success of the 1937 Pittman-Robertson Act, which funds state wildlife agencies through a federal excise tax on guns and ammunition. That law was adopted to address a decline in game species that had hunters alarmed. The state refuges and other programs it funded are why deer, ducks and Wild Turkeys are no longer scarce.

The recovery act would provide $1.3 billion a year to states and nearly $100 million to Native American tribes to conserve nongame species. It has bipartisan support, in part, Stein says, because it would help arrest the decline of a species before the ESA's “regulatory hammer” falls. Although it would be a large boost to state wildlife budgets, the funding would be a rounding error in federal spending. But last year Congress couldn't agree on how to pay for the measure. Passage “would be a really big deal for nature,” Curry says.

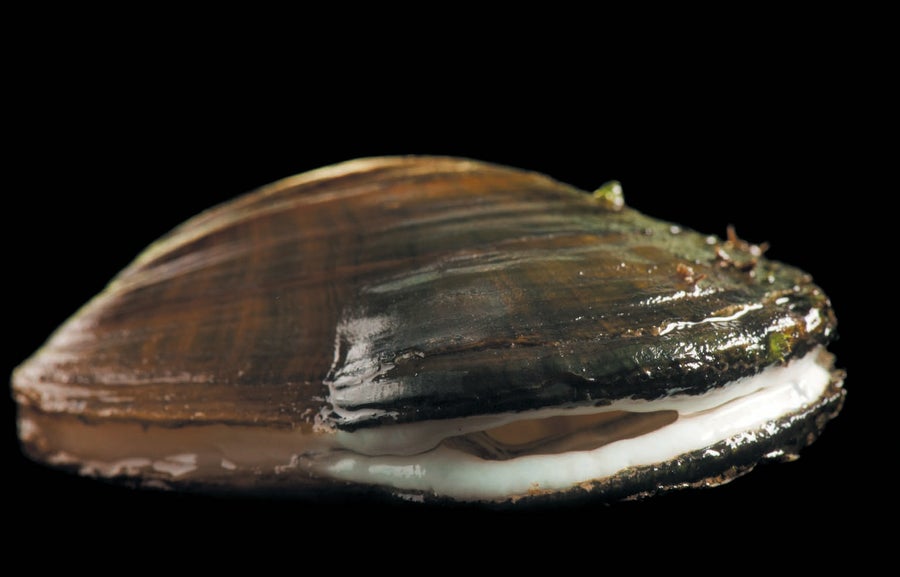

Oyster Mussel. Epioblasma capsaeformis. Listed as Endangered: 1997. Status: Still endangered. Credit: © Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark

The second initiative that could promote species conservation is already underway: bringing landowners into the fold. Most wildlife habitat east of the Rocky Mountains is on private land. That's also where habitat loss is happening fastest. Some experts say conservation isn't likely to succeed unless the FWS works more collaboratively with landowners, adding carrots to the ESA's regulatory stick. Bean has long promoted the idea, including when he worked at the Interior Department from 2009 to early 2017. The approach started, he says, with the Red-cockaded Woodpecker.

When the ESA was passed, there were fewer than 10,000 Red-cockaded Woodpeckers left of the millions that had once lived in the Southeast. Humans had cut down the old pine trees, chiefly Longleaf Pine, that the birds excavate cavities in for roosting and nesting. An appropriate tree has to be large, at least 60 to 80 years old, and there aren't many like that left. The longleaf forest, which once carpeted up to 90 million acres from Virginia to Texas, has been reduced to less than three million acres of fragments.

In the 1980s the ESA wasn't helping because it provided little incentive to preserve forest on private land. In fact, Bean says, it did the opposite: landowners would sometimes clear-cut potential woodpecker habitat just to avoid the law's constraints. The woodpecker population continued to drop until the 1990s. That's when Bean and his Environmental Defense Fund colleagues persuaded the FWS to adopt “safe-harbor agreements” as a simple solution. An agreement promised landowners that if they let pines grow older or took other woodpecker-friendly measures, they wouldn't be punished; they remained free to decide later to cut the forest back to the baseline condition it had been in when the agreement was signed.

That modest carrot was inducement enough to quiet the chainsaws in some places. “The downward trends have been reversed,” Bean says. “In places like South Carolina, where they have literally hundreds of thousands of acres of privately owned forest enrolled, Red-cockaded Woodpecker numbers have shot up dramatically.”

The woodpecker is still endangered. It still needs help. Because there aren't enough old pines, land managers are inserting lined, artificial cavities into younger trees and sometimes moving birds into them to expand the population. They are also using prescribed fires or power tools to keep the longleaf understory open and grassy, the way fires set by lightning or Indigenous people once kept it and the way the woodpeckers like it. Most of this work is taking place, and most Red-cockaded Woodpeckers are still living, on state or federal land such as military bases. But a lot more longleaf must be restored to get the birds delisted, which means collaborating with private landowners, who own 80 percent of the habitat.

Leo Miranda-Castro, who retired last December as director of the FWS's southeast region, says the collaborative approach took hold at regional headquarters in Atlanta in 2010. The Center for Biological Diversity had dropped a “mega petition” demanding that the FWS consider 404 new species for listing. The volume would have been “overwhelming,” Miranda-Castro says. “That's when we decided, ‘Hey, we cannot do this in the traditional way.’ The fear of listing so many species was a catalyst” to look for cases where conservation work might make a listing unnecessary.

An agreement affecting the Gopher Tortoise shows what is possible. Like the woodpeckers, it is adapted to open-canopied longleaf forests, where it basks in the sun, feeds on herbaceous plants and digs deep burrows in the sandy soil. The tortoise is a keystone species: more than 300 other animals, including snakes, foxes and skunks, shelter in its burrows. But its numbers have been declining for decades.

Urbanization is the main threat to the tortoises, but timberland can be managed in a way that leaves room for them. Eager to keep the species off the list, timber companies, which own 20 million acres in its range, agreed to figure out how to do that—above all by returning fire to the landscape and keeping the canopy open. One timber company, Resource Management Service, said it would restore Longleaf Pine on about 3,700 acres in the Florida panhandle, perhaps expanding to 200,000 acres eventually. It even offered to bring other endangered species onto its land, which delighted Miranda-Castro: “I had never heard about that happening before.” Last fall the FWS announced that the tortoise didn't need to be listed in most of its range.

Miranda-Castro now directs Conservation Without Conflict, an organization that seeks to foster conversation and negotiation in settings where the ESA has more often generated litigation. “For the first 50 years the stick has been used the most,” Miranda-Castro says. “For the next 50 years we're going to be using the carrots way more.” On his own farm outside Fort Moore, Ga., he grows Longleaf Pine—and Gopher Tortoises are benefiting.

Whooping Crane. Grus americana. Listed as Endangered: 1967. Status: Still endangered. Credit: © Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark

The Center for Biological Diversity doubts that carrots alone will save the reptile. It points out that the FWS's own models show small subpopulations vanishing over the next few decades and the total population falling by nearly a third. In August 2023 it filed suit against the FWS, demanding the Gopher Tortoise be listed.

The FWS itself resorted to the stick this year when it listed the Lesser Prairie-Chicken, a bird whose grassland home in the Southern Plains has long been encroached on by agriculture and the energy industry. The Senate promptly voted to overturn that listing, but President Biden promised to veto that measure if it passes the House.

B ehind the debates over strategy lurks the vexing question: Can we save all species? The answer is no. Extinctions will keep happening. In 2021 the FWS proposed to delist 23 more species—not because they had recovered but because they hadn't been seen in decades and were presumed gone. There is a difference, though, between acknowledging the reality of extinction and deliberately deciding to let a species go. Some people are willing to do the latter; others are not. Bean thinks a person's view has a lot to do with how much they've been exposed to wildlife, especially as a child.

Zygmunt Plater, a professor emeritus at Boston College Law School, was the attorney in the 1978 Snail Darter case, fighting for hundreds of farmers whose land would be submerged by the Tellico Dam. At one point in the proceedings Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr., asked him, “What purpose is served, if any, by these little darters? Are they used for food?” Plater thinks creatures such as the darter alert us to the threat our actions pose to them and to ourselves. They prompt us to consider alternatives.

The ESA aims to save species, but for that to happen, ecosystems have to be preserved. Protecting the Northern Spotted Owl has saved at least a small fraction of old-growth forest in the Pacific Northwest. Concern about the Red-cockaded Woodpecker and the Gopher Tortoise is aiding the preservation of longleaf forests in the Southeast. The Snail Darter wasn't enough to stop the Tellico Dam, which drowned historic Cherokee sites and 300 farms, mostly for real estate development. But after the controversy, the presence of a couple of endangered mussels did help dissuade the TVA from completing yet another dam, on the Duck River in central Tennessee. That river is now recognized as one of the most biodiverse in North America.

The ESA forced states to take stock of the wildlife they harbored, says Jim Williams, who as a young biologist with the FWS was responsible for listing both the Snail Darter and mussels in the Duck River. Williams grew up in Alabama, where I live. “We didn't know what the hell we had,” he says. “People started looking around and found all sorts of new species.” Many were mussels and little fish. In a 2002 survey, Stein found that Alabama ranked fifth among U.S. states in species diversity. It also ranks second-highest for extinctions; of the 23 extinct species the FWS recently proposed for delisting, eight were mussels, and seven of those were found in Alabama.

One morning this past spring, at a cabin on the banks of Shoal Creek in northern Alabama, I attended a kind of jamboree of local freshwater biologists. At the center of the action, in the shade of a second-floor deck, sat Sartore. He had come to board more species onto his photo ark, and the biologists—most of them from the TVA—were only too glad to help, fanning out to collect critters to be decanted into Sartore's narrow, flood-lit aquarium. He sat hunched before it, a black cloth draped over his head and camera, snapping away like a fashion photographer, occasionally directing whoever was available to prod whatever animal was in the tank into a more artful pose.

As I watched, he photographed a striated darter that didn't yet have a name, a Yellow Bass, an Orangefin Shiner and a giant crayfish discovered in 2011 in the very creek we were at. Sartore's goal is to help people who never meet such creatures feel the weight of extinction—and to have a worthy remembrance of the animals if they do vanish from Earth.

With TVA biologist Todd Amacker, I walked down to the creek and sat on the bank. Amacker is a mussel specialist, following in Williams's footsteps. As his colleagues waded in the shoals with nets, he gave me a quick primer on mussel reproduction. Their peculiar antics made me care even more about their survival.

There are hundreds of freshwater mussel species, Amacker explained, and almost every one tricks a particular species of fish into raising its larvae. The Wavy-rayed Lampmussel, for example, extrudes part of its flesh in the shape of a minnow to lure black bass—and then squirts larvae into the bass's open mouth so they can latch on to its gills and fatten on its blood. Another mussel dangles its larvae at the end of a yard-long fishing line of mucus. The Duck River Darter Snapper—a member of a genus that has already lost most of its species to extinction—lures and then clamps its shell shut on the head of a hapless fish, inoculating it with larvae. “You can't make this up,” Amacker said. Each relationship has evolved over the ages in a particular place.

The small band of biologists who are trying to cultivate the endangered mussels in labs must figure out which fish a particular mussel needs. It's the type of tedious trial-and-error work conservation biologists call “heroic,” the kind that helped to save California Condors and Whooping Cranes. Except these mussels are eyeless, brainless, little brown creatures that few people have ever heard of.

For most mussels, conditions are better now than half a century ago, Amacker said. But some are so rare it's hard to imagine they can be saved. I asked Amacker whether it was worth the effort or whether we just need to accept that we must let some species go. The catch in his voice almost made me regret the question.

“I'm not going to tell you it's not worth the effort,” he said. “It's more that there's no hope for them.” He paused, then collected himself. “Who are we to be the ones responsible for letting a species die?” he went on. “They've been around so long. That's not my answer as a biologist; that's my answer as a human. Who are we to make it happen?”

Robert Kunzig is a freelance writer in Birmingham, Ala., and a former senior editor at National Geographic, Discover and Scientific American .

Endangered Species

- Educational Resources

- Wildlife Guide

- Understanding Conservation

What is an "Endangered Species"?

An endangered species is an animal or plant that's considered at risk of extinction. A species can be listed as endangered at the state, federal, and international level. On the federal level, the endangered species list is managed under the Endangered Species Act.

The Endangered Species Act (ESA) was enacted by Congress in 1973. Under the ESA, the federal government has the responsibility to protect endangered species (species that are likely to become extinct throughout all or a large portion of their range), threatened species (species that are likely to become endangered in the near future), and critical habitat (areas vital to the survival of endangered or threatened species).

The Endangered Species Act has lists of protected plant and animal species both nationally and worldwide. When a species is given ESA protection, it is said to be a "listed" species. Many additional species are evaluated for possible protection under the ESA, and they are called “candidate” species.

Why We Protect Them

The Endangered Species Act is very important because it saves our native fish, plants, and other wildlife from going extinct. Once gone, they're gone forever, and there's no going back. Losing even a single species can have disastrous impacts on the rest of the ecosystem, because the effects will be felt throughout the food chain. From providing cures to deadly diseases to maintaining natural ecosystems and improving overall quality of life, the benefits of preserving threatened and endangered species are invaluable.

How a Species Gets Listed

When the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service or the National Marine Fisheries Service is investigating the health of a species, they look at scientific data collected by local, state, and national scientists. In order to be listed as a candidate, a species has to qualify for protected status under the Endangered Species Act. Whether or not a species is listed as endangered or threatened then depends on a number of factors, including the urgency and whether adequate protections exist through other means.

When deciding whether a species should be added to the Endangered Species List, the following criteria are evaluated:

- Has a large percentage of the species' vital habitat been degraded or destroyed?

- Has the species been over-consumed by commercial, recreational, scientific or educational uses?

- Is the species threatened by disease or predation?

- Do current regulations or legislation inadequately protect the species?

- Are there other man-made factors threatening the long-term survival of the species?

If the answer to one or more of the above questions is yes, then the species can be listed under the Endangered Species Act.

Species Protections

Once a species becomes listed as "threatened" or "endangered," it receives special protections by the federal government. Animals are protected from “take” and being traded or sold. A listed plant is protected if on federal property or if federal actions are involved, such as the issuing of a federal permit on private land.

The term "take" is used in the Endangered Species Act to include "harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill trap, capture, or collect, or to attempt to engage in any such conduct." The law also protects against interfering in vital breeding and behavioral activities or degrading critical habitat.

The primary goal of the Endangered Species Act is to make species' populations healthy and vital so they can be delisted from the Endangered Species Act. Under the Endangered Species Act, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service oversees the listing and protection of all terrestrial animals and plants as well as freshwater fish. NOAA's National Marine Fisheries Service oversees marine fish and wildlife. The two organizations actively invest time and resources to help bring endangered or threatened species back from the brink of extinction.

Endangered Species Day

Endangered Species Day, which falls on the third Friday in May each year, is a day to celebrate endangered species success stories and learn about species still in danger. Learn what the National Wildlife Federation is doing to protect endangered species and how to support Endangered Species Day.

Six Stories of Success

Learn about the life-saving efforts that led to celebrated comebacks.

Get Involved

Donate Today

Sign a Petition

Donate Monthly

Nearby Events

Sign Up for Updates

What's Trending

"Better" Chocolate for a Sweeter World

Chocolate is sweet but the bitter truth is that its industry is linked to harmful practices like forced labor and deforestation. Explore the ongoing efforts and find out how you can contribute to the movement for "better" chocolate.

Take the Pledge

Encourage your mayor to take the Mayors' Monarch Pledge and support monarch conservation before April 30!

UNNATURAL DISASTERS

A new storymap connects the dots between extreme weather and climate change and illustrates the harm these disasters inflict on communities and wildlife.

Creating Safe Spaces

Promoting more-inclusive outdoor experiences for all

Where We Work

More than one-third of U.S. fish and wildlife species are at risk of extinction in the coming decades. We're on the ground in seven regions across the country, collaborating with 52 state and territory affiliates to reverse the crisis and ensure wildlife thrive.

- ACTION FUND

PO Box 1583, Merrifield, VA 22116-1583

800.822.9919

Join Ranger Rick

Inspire a lifelong connection with wildlife and wild places through our children's publications, products, and activities

- Terms & Disclosures

- Privacy Policy

- Community Commitment

National Wildlife Federation is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization

You are now leaving nwf.org

In 4 seconds , you'll be redirected to our Action Center at www.nwfactionfund.org.

Professor Holly Doremus‘s article, The Endangered Species Act: Static Law Meets Dynamic World, traces the history of the Endangered Species Act ("ESA") to illustrate the need to correct the assumption that nature is simple to manage. For all its flaws, the ESA remains the nation's primary biodiversity conservation act,although the construct had not been "invented" in 1973 when Congress enacted "one of the last pieces of environmental bandwagon legislation." Yet, it is difficult to adapt to the broader objective of biodiversity conservation, in part because the ESA rests on a static view of species and the landscapes and watercourses in which they live. In the future, especially as we deal with global climate change's impacts on biodiversity, evolutionary theory and adaptive management must be incorporated into the Act, even as old certainties like the definition of species become muddied.

Endangered species, Statics & dynamics (Social sciences), United States. National Marine Fisheries Service, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, United States. Endangered Species Act of 1973, Environmental management, Wildlife conservation

Download pdf View PDF

- Download pdf

- Volume 32 • Issue 1 • 2010

Publication details

All rights reserved

File Checksums (MD5)

- pdf: e2c4e0fccfdeec73f369a5121f167351

Non Specialist Summary

This article has no summary

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

JavaScript appears to be disabled on this computer. Please click here to see any active alerts .

Summary of the Endangered Species Act

- ESA, from NOAA

- The official text of the ESA is available in the United States Code , from the US Government Printing Office

16 U.S.C. §1531 et seq. (1973)

- The FWS maintains a worldwide list of endangered species . Species include birds, insects, fish, reptiles, mammals, crustaceans, flowers, grasses, and trees.

- U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries Service .

The law requires federal agencies, in consultation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and/or the NOAA Fisheries Service, to ensure that actions they authorize, fund, or carry out are not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of any listed species or result in the destruction or adverse modification of designated critical habitat of such species. The law also prohibits any action that causes a "taking" of any listed species of endangered fish or wildlife. Likewise, import, export, interstate, and foreign commerce of listed species are all generally prohibited.

Endangered Species and EPA

The Office of Pesticide Programs (OPP) implements key portions of the Endangered Species Act. OPP regulates the use of all pesticides in the United States and establishes maximum levels for pesticide residues in food, thereby safeguarding the nation's food supply.

- Protecting Endangered Species from Pesticides

- Laws & Regulations Home

- By Business Sector

- Enforcement

- Laws & Executive Orders

- Regulations

Trending News

Related Practices & Jurisdictions

- Environmental, Energy & Resources

- Administrative & Regulatory

- All Federal

On March 28, 2024, the Biden Administration released three final rules that significantly revise regulations, previously promulgated in 2019, that implement several sections of the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”). The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (“FWS”) and the National Marine Fisheries Service (“NMFS”) (collectively, the “Services”) finalized regulations that amend or reverse several components of the ESA regulations implementing Section 4 (listing of species as threatened or endangered and the designation of critical habitat) and Section 7 (consultation procedures). Additionally, FWS finalized regulations reinstating its “blanket rule” under Section 4(d) (application of the ESA’s “take” prohibitions to threatened species). The final rules are scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on April 5, 2024, and should become effective May 6, 2024.

The species and habitat protected under the ESA extend to all aspects of our communities, lands, and waters. There are almost 2,400 species listed as threatened or endangered pursuant to ESA Section 4. Critical habitat for one or more species has been designated in all regions of the U.S. and its territories. Through the Section 7 consultation process and “take” prohibitions under Sections 9 and 4(d), the ESA imposes species and habitat protection measures on the use and management of private, federal, and state lands and waters and, consequently, on governmental and private activities.

Pursuant to President Biden’s Executive Order 13990 , the Services reviewed certain agency actions taken under the prior administration and identified five final rules related to ESA implementation that should be reconsidered. In 2022, the Services rescinded two of those final rules—the regulatory definition of “habitat” for the purpose of designating critical habitat and the regulatory procedures for excluding areas from critical habitat designations. While the three final rules released on March 28 reflect the consummation of that initial effort, the Services are currently preparing additional revisions to other ESA regulations and policies.

Revisions to the Regulations for Listing Species and Designating Critical Habitat

Section 4 of the ESA dictates how the Services list species as threatened or endangered, delist or reclassify species, and designate areas as critical habitat. The final rule makes several targeted revisions to these procedures. Notable changes include:

- Evaluation of the “foreseeable future” for threatened species: The final rule revises the applicable regulatory framework to state that “[t]he foreseeable future extends as far into the future as the Services can make reasonably reliable predictions about the threats to the species and the species’ responses to those threats.” The Services decline to set a predetermined number of years or period of time and will evaluate the foreseeable future on a species-by-species basis.

- Designation of unoccupied critical habitat: The final rule revises the process for determining when unoccupied areas may be designated as critical habitat. The Services remove the requirement that they “will only consider” unoccupied areas to be essential when a designation limited to occupied critical habitat would be inadequate for the conservation of the species. The Services also remove the provision that an unoccupied area is considered essential when there is reasonable certainty both that the area will contribute to the conservation of the species and that it contains one or more physical or biological features essential to the conservation of the species.

- Not prudent determinations for critical habitat designation: The final rule removes the justification for making a not prudent determination when threats to a species’ habitat are from causes that cannot be addressed through management actions in a Section 7 consultation. The Services note that this is intended to address the misperception that a designation of critical habitat could be declined for species impacted by climate change.

- Factors for delisting species: The final rule clarifies that a species will be delisted if it has recovered to the point at which it no longer meets the definition of an endangered species or a threatened species. A species also will be delisted if it is extinct or new information since the original listing decision shows that the listed entity does not meet the definition of a species, an endangered species, or a threatened species.

- Economic impacts in classification process: The Services restore the regulatory condition that a species listing determination is to be made “without reference to possible economic or other impacts of such determination.”

Revisions to the Consultation Regulations

The ESA Section 7 consultation requirement applies to discretionary federal agency actions—including federal permits, licenses and authorizations, management of federal lands, and other federal programs. Federal actions that are likely to adversely affect a listed species or designated critical habitat must undergo a formal consultation review and issuance of a biological opinion evaluating whether the action is likely to jeopardize the continued existence of a species or result in the destruction or adverse modification of critical habitat. The biological opinion also evaluates the extent to which “take” of a listed species may occur as a result of the action and quantifies the level of incidental take that is authorized. The final rule makes the following notable changes to the applicable regulations:

- Expanded scope of reasonable and prudent measures (RPMs): The final rule revises and expands the scope of RPMs that can be included as part of an incidental take statement in a biological opinion. In a change from their prior interpretation, and in addition to measures that avoid or minimize impacts of take, the Services can include measures as an RPM that offset any remaining impacts of incidental take that cannot be avoided (e.g., for certain impacts, offsetting measures could include restoring or protecting suitable habitat). The Services also allow RPMs, and their implementing terms and conditions, to occur inside or outside of the action area. Any offsetting measures are subject to the requirement that RPMs may only involve “minor changes” to the action, must be commensurate with the scale of the impact, and must be within the authority and discretion of the action agency or applicant to carry out.

- Revised definition of “effects of the action”: In an effort to clarify that the consequences to listed species or critical habitat that are included within effects of the action relate to both the proposed action and activities that are caused by the proposed action, the final rule adds a phrase to the definition to note that it includes “the consequences of other activities that are caused by the proposed action but that are not part of the action .” In addition, the final rule removes provisions at 50 C.F.R. § 402.17, added in 2019, which provide the factors used to determine whether an activity or a consequence is “reasonably certain to occur.”

- Revised definition of “environmental baseline”: The final rule revises the definition in an effort to more clearly address the question of a federal agency’s discretion over its own activities and facilities when determining what is included within the environmental baseline. The Services note that it is the federal action agency’s discretion to modify the activity or facility that is the determining factor when deciding which impacts of an action agency’s activity or facility should be included in the environmental baseline, as opposed to the effects of the action. For ongoing actions, in the preamble, the Services state that past impacts would be included in the environmental baseline, and the future consequences of the proposed federal action would be the subject of the consultation’s effects of the action analysis—i.e., “an effects analysis may need to assess the future and extended life of a structure yet the past existence and impacts of the structure are included in the environmental baseline.”

- Clarification of obligation to reinitiate consultation: The final rule removes the phrase “or by the Service” to clarify that it is the federal action agency, and not the Services, that has the obligation to request reinitiation of consultation when one or more of the triggering criteria have been met (and discretionary involvement or control over the action is retained).

The Services state that they intend to provide additional guidance in an updated ESA Section 7 Consultation Handbook (last revised in 1998) that is anticipated to be made available for public comment.

Reinstatement of Blanket Protections for FWS Species Listed as Threatened

Pursuant to the ESA, threatened and endangered species are treated differently with respect to what are often called the “take” prohibitions of the Act. In part, ESA Section 9(a)(1) prohibits the unauthorized take—which is defined as an act “to harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect”—of an endangered species. In contrast, under Section 4(d) of the ESA, the Secretary may issue a regulation applying any prohibition set forth in Section 9(a)(1) to a threatened species. Historically, FWS applied a “blanket 4(d) rule” that automatically extended all ESA Section 9(a)(1) prohibitions to a threatened species unless a species-specific rule was otherwise adopted. In 2019, FWS revised its approach to align with NMFS’s long-standing practice, which only applies the ESA prohibitions to threatened species on a species-specific basis. The final rule makes the following changes to FWS’s approach under Section 4(d):

- Reinstate blanket 4(d) rule: FWS reinstates the general application of the “blanket 4(d) rule” to newly listed threatened species. As before, FWS retains the option to promulgate species-specific rules that revise the scope or application of the prohibitions that would apply to threatened species.

- New exception for Tribes: The final rule extends to federally recognized Tribes the ability currently afforded to FWS and other federal and state agencies to aid, salvage, or dispose of threatened species.

Implications

These final rules perpetuate the ongoing fluctuation that has become prevalent with respect to the ESA regulatory landscape as each Administration reevaluates and revises the ESA policies and priorities of prior Administrations. In addition, the durability of these regulations will likely be tested through litigation, as both environmental and industry groups have signaled likely legal challenges.

Current Legal Analysis

More from van ness feldman llp, upcoming legal education events.

Sign Up for e-NewsBulletins

- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

Endangered Species Act, Research Paper Example

Pages: 8

Words: 2174

Hire a Writer for Custom Research Paper

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

Should the Endangered Species Act Be Strengthened?

Introduced in 1973, the Endangered Species Act was legislation passed with the intent of saving a number of critical animal, plant and bird species from the brink of extinction. Although hardly perfect, it was the best attempt up to that time to protect America’s natural resources from one of the greatest mass extinctions the world has ever seen. Although it is true that extinction happens all the time, as nature is continuously evolving, this current extinction period is unique because it marks the first time that extinction of this caliber has occurred directly because of man. “What is new is that the current rate of human-induced extinction appears far higher than would be implied by the past fossil records. Conservative estimates of global rates of extinction for various groups of species vary from 10 to 1,000 times the natural rates that would currently prevail.” (Brown and Shogren 1998) This worries many scientists because of the unknown repercussions of species loss and how it will affect both human life and the life of the planet. The Endangered Species Act has caused a great amount of controversy because it appeals to people on a number of emotional levels. The ESA is touted by some environmentalists to be an effective, positive and successful piece of legislature, while other environmentalists say that it is not tough enough, and needs to be strengthened. Then there are the opponents, who charge that the ESA places too much burden on private land owners, and that the Act as is inhibits economic growth without proper scientific reason. There are some that say the ESA has failed entirely and an entirely new set of legislation needs to be created. Everyone tends to agree that protecting the environment and biological diversity is important. However, it is more difficult to reconcile the two sides, balancing species and habitat protection with property rights and personal freedom. In order for a more balanced and successful conservation act to be passed, it will be necessary for scientists and biologists to provide a new framework on the dynamic of species conservation and for the economic impact to be more fairly balanced between the Federal and State governments and the rights and freedoms of individual property owners.

The current rate of species extinction has many people concerned for a number of reasons. Extinction not only threatens the natural world in terms of biodiversity for its aesthetic and intrinsic values, it also threatens industry that is dependent on it, such as the fishing industry. “Today, human activities are an important cause of species loss mostly because humans destroy or alter habitat bust also because of hunting (including commercial fishing), the introduction of foreign species as novel competitors, and the introduction of diseases.” (Easton 2008) The Endangered Species Act was enacted to protect the planets natural resources for future generations. However, its successfulness has been debated. Proponents say that the ESA has been very successful in bringing back targeted species from the brink of extinction.

Critics of the ESA consistently point out the single species approach as being one of the main flaws of the Act. Though proponents point out the fact that high profile animals, such as the gray wolf and the bald eagle, both of which whose populations had reached a critical at the time the ESA was approved, have been so successfully impacted by the ESA that these animals have actually been removed from the list. Though ESA has proven successful in the past by barring “construction projects that would further threaten endangered species” (Easton 2008) its main emphasis continues to be on single species conservation. One of the main issues that biologists and ecologists have with this approach is that it is impossible for a species to recover, and maintain it population, if sufficient habitat is not available to support it. “Legal experts as well as biologists have criticized the Act’s single-species approach to biodiversity conservation. This approach has been a traditional element of conservation regulations due to the historical fact that overhunting and other forms of direct exploitation depleted or extirpated many species; however, today species face greater threats due to habitat reduction, making ecosystem conservation preferable to single-species protection.” (Rohlf 1991) Habitat conservation has many benefits besides protecting the targeted species, as well. Other non-threatened species will also benefit by having habitat protected, and will not be faced with population reductions. Protecting habitat also benefits humans by, for example, maintaining critical watersheds which are essential to clean and fresh drinking water.

Although the ESA has had success in the past with habitat protection by using it to protect key stone species, efforts are hindered by politics. Although not an official policy of the Act, it often occurs that high-profile species, including mammals and birds, are often favored above species that are not as glamorous species, such as insects, amphibians and plants. This is not what the Act endorses, as Rohlf (1991) explains that even a conference committee report noted that protected species “must be viewed in terms of their relationship to the ecosystem of which they form a constituent element (House of Representatives 1982). Even though both science and policy makers both agree that habitat conservation should be the priority of conservation efforts, it is still the high profile species that act as spokesmen for the Act.

Since the ESA has been successful in the past, proponents claim, it is necessary now for the legislation to be taken to the next step, by strengthening the act and empowering the federal government with more power to protect species over private industry and landowner rights. In his argument, John Kostyack (Easton 2008) lists the benefits the ESA has brought to species through its protection. He states that “Over 98% of species ever protected by the Act remain on the planet today. Of the listed species whose condition is known, 68% are stable or improving and 32% are declining. The longer a species enjoys the ESA’s protection, the more likely its condition will stabilize or improve.” (Easton 2008). These numbers seem to indicate an overwhelmingly positive effect due to the ESA. However, there is another side.

Data and numbers are tricky because they can be manipulated into telling two conflicting stories. Opponents use the same numbers as proponents but a different outcome is concluded. In the history of the ESA, only 13 species have ever been removed from the endangered species rate, leading opponents of the law to state that the ESA has only a 1% success rate, which seems small and unsubstantial and far from successful. “In the seventeen years since the passage of the Act in 1973, only a handful of protected species have recovered to the point where they no longer face extinction. Meanwhile, estimates that human actions extirpate 17,500 species each year.” (Rohlf 1991) The factors for the ESA’s lack of success include politics and economics. Due to this low success rate, opponents claim, and the stress the law puts on private landowners, the law needs drastic revision and overhaul. Despite the fact that ESA proponents see success in the numbers, opponents see failure and need for change.