- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Code Switch

- School Colors

- Perspectives

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

Commentary: Cultural Appropriation Is, In Fact, Indefensible

K. Tempest Bradford

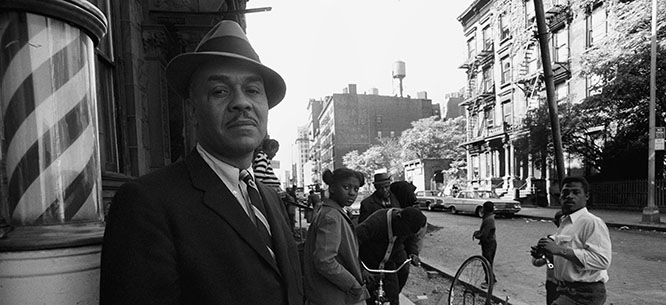

Elvis Presley, in the studio in 1956 — Presley's success was undoubtedly driven by the material he appropriated from black musicians. Bettmann Archive/Getty Images hide caption

Elvis Presley, in the studio in 1956 — Presley's success was undoubtedly driven by the material he appropriated from black musicians.

Last week, the New York Times published an op-ed titled "In Defense of Cultural Appropriation" in which writer Kenan Malik attempted to extol the virtues of artistic appropriation and chastise those who would stand in the way of necessary "cultural engagement." (No link, because you have Google and I'd rather not give that piece more traffic than it deserves.) What would have happened, he argues, had Elvis Presley not been able to swipe the sounds of black musicians?

Malik is not the first person to defend cultural appropriation. He joins a long list that, most recently, has included prominent members of the Canadian literary community and author Lionel Shriver.

But the truth is that cultural appropriation is indefensible. Those who defend it either don't understand what it is, misrepresent it to muddy the conversation, or ignore its complexity — discarding any nuances and making it easy to dismiss both appropriation and those who object to it.

At the start of the most recent debate , Canadian author Hal Niedzviecki called on the readers of Write magazine to "Write what you don't know ... Relentlessly explore the lives of people who aren't like you. ... Win the Appropriation Prize." Amid the outcry over this editorial, there were those who wondered why this statement would be objectionable. Shouldn't authors "write the Other?" Shouldn't there be more representative fiction?

Yes, of course. The issue here is that Niedzviecki conflated cultural appropriation and the practice of writing characters with very different identities from yourself — and they're not the same thing. Writing inclusive fiction might involve appropriation if it's done badly, but that's not a given.

Cultural appropriation can feel hard to get a handle on, because boiling it down to a two-sentence dictionary definition does no one any favors. Writer Maisha Z. Johnson offers an excellent starting point by describing it not only as the act of an individual, but an individual working within a " power dynamic in which members of a dominant culture take elements from a culture of people who have been systematically oppressed by that dominant group ."

That's why appropriation and exchange are two different things, Johnson says — there's no power imbalance involved in an exchange. And when artists appropriate, they can profit from what they take, while the oppressed group gets nothing.

Related NPR Stories

'Columbusing': The Art Of Discovering Something That Is Not New

Don't Call It 'The New Ramen': Why Pho Is Central To Vietnamese Identity

Dear white artists making music videos in india: step away from the 'holi' powder, author lionel shriver on cultural appropriation and the 'sensitivity police'.

I teach classes and seminars alongside author and editor Nisi Shawl on Writing the Other , and the foundation of our work is that authors should create characters from many different races, cultures, class backgrounds, physical abilities, and genders, even if — especially if — these don't match their own. We are not alone in this. You won't find many people advising authors to only create characters similar to themselves. You will find many who say: Don't write characters from minority or marginalized identities if you are not going to put in the hard work to do it well and avoid cultural appropriation and other harmful outcomes. These are different messages. But writers often see or hear the latter and imagine that it means the former. And editorials like Niedzviecki's don't help the matter.

Complicating things even further, those who tend to see appropriation as exchange are often the ones who profit from it.

Even Malik's example involving rock and roll isn't as simple as Elvis "stealing" from black artists. Before he even came along, systematic oppression and segregation in America meant black musicians didn't have access to the same opportunities for mainstream exposure, income, or success as white ones. Elvis and other rock and roll musicians were undoubtedly influenced by black innovators, but over time the genre came to be regarded as a cultural product created, perfected by, and only accessible to whites .

This is the "messy interaction" Malik breezes over in dismissing the idea of appropriation as theft: A repeating pattern that's recognizable across many different cultural spheres, from fashion and the arts to literature and food.

And this pattern is why cultures and people who've suffered the most from appropriation sometimes insist on their traditions being treated like intellectual property — it can seem like the only way to protect themselves and to force members of dominant or oppressive cultures to consider the impact of their actions.

This has lead to accusations of gatekeeping by Malik and others: Who has the right to decide what is appropriation and what isn't ? What does true cultural exchange look like? There's no one easy answer to either question.

But there are some helpful guidelines: The Australian Council for the Arts developed a set of protocols for working with Indigenous artists that lays out how to approach Aboriginal culture as a respectful guest, who to contact for guidance and permission, and how to proceed with your art if that permission is not granted. Some of these protocols are specific to Australia, but the key to all of them is finding ways for creativity to flourish while also reducing harm.

All of this lies at the root of why cultural appropriation is indefensible. It is, without question, harmful. It is not inherent to writing representational and inclusive fiction, it is not a process of equal and mutually beneficial exchange, and it is not a way for one culture to honor another. Cultural appropriation does damage, and it should be something writers and other artists work hard to avoid, not compete with each other to achieve.

For those who are willing to do that hard work, there are resources out there. When I lecture about this, I ask writers to consider whether they are acting as Invaders, Tourists, or Guests, according to the excellent framework Nisi Shawl lays out in her essay on appropriation . And then I point them towards all the articles and blog posts I've collected over time on the subject of cultural appropriation , to give them as full a background in understanding, identifying, and avoiding it as I possibly can.

Because I believe that, instead of giving people excuses for why appropriation can't be avoided (it can), or allowing them to think it's no big deal (it is), it's more important to help them become better artists whose creations contribute to cultural understanding and growth that benefits us all.

K. Tempest Bradford is a speculative fiction author, media critic, teacher, and podcaster. She teaches and lectures about writing inclusive fiction online and in person via WritingTheOther.com .

Home — Essay Samples — Sociology — Sociological Theories — Cultural Appropriation

Essays on Cultural Appropriation

The business of fancydancing analysis, the use of cultural appropriation to foster cultural appreciation, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

Cultural Appropriation and How It Can Cause Harm

Negative impact of cultural appropriation, the cultural appropriation in the america, connection between music and cultural appropriation, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Cultural Appropriation: Why Humans Define Nature Differently

The negative connotation surrounding cultural appropriation, john stuart mill and his ideas about cultural appropriation, the cultural plunge: an exploration of benefits and challenges.

Cultural appropriation refers to the adoption, borrowing, or imitation of elements, practices, symbols, or artifacts from a marginalized culture by individuals or groups belonging to a dominant culture, often without proper understanding, respect, or acknowledgment of the cultural context or significance. It involves the selective appropriation of certain aspects of a culture, typically for personal gain, fashion trends, or entertainment, while disregarding the historical, social, or religious meaning behind those elements.

Cultural appropriation, as a concept, traces its origins to the early 20th century, primarily in the field of anthropology and cultural studies. It emerged as a way to address the power dynamics and inequalities that exist between different cultures. The history of cultural appropriation can be seen within the context of colonialism and imperialism, where dominant cultures often appropriated elements from marginalized or colonized cultures for their own benefit. This included the appropriation of cultural symbols, artifacts, clothing, music, and other cultural practices. The discourse around cultural appropriation gained significant attention and evolved throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. It has become a subject of debate and critique, raising questions about cultural sensitivity, respect, and the commodification of cultural elements. Proponents argue that cultural exchange is beneficial and can foster understanding, while critics assert that appropriation can perpetuate stereotypes, exploit cultures, and erase the significance of cultural practices.

In the US, cultural appropriation is often observed in the realm of fashion, music, art, and even Halloween costumes, where elements from different cultures are sometimes used without proper understanding or respect. This can range from the adoption of cultural hairstyles, attire, or religious symbols to the appropriation of cultural rituals and practices. The public opinion on cultural appropriation in the US is diverse. Some individuals view it as a form of appreciation and cultural exchange, while others perceive it as a form of disrespect, erasure, and even exploitation of marginalized communities. Activists and social media platforms play a crucial role in raising awareness about cultural appropriation, promoting dialogue, and encouraging individuals to be mindful of the cultural origins and significance of what they adopt or represent. As society becomes more aware of the complexities surrounding cultural appropriation, there is a growing emphasis on fostering cultural understanding, respecting cultural boundaries, and engaging in responsible cultural exchange. The conversation on cultural appropriation in the US continues to evolve, highlighting the importance of education, empathy, and sensitivity to different cultures and their histories.

Fashion and Style: This includes the adoption of cultural attire, accessories, or hairstyles without understanding their cultural significance. Examples include wearing Native American headdresses or African tribal prints without knowledge or respect for their cultural context. Language and Slang: Appropriating language or slang terms from different cultures without understanding their origins can be seen as a form of cultural appropriation. This often happens when words or phrases are taken out of their original cultural context and used without proper understanding or respect. Music and Dance: Borrowing elements of music and dance from different cultures without giving credit or respecting the cultural roots is another form of cultural appropriation. This can involve taking traditional music styles, instruments, or dance moves and using them without acknowledging their cultural significance. Art and Symbols: Appropriation of cultural symbols, religious icons, or traditional artwork without understanding their cultural meanings can be seen as disrespectful. It involves using these symbols for aesthetic purposes or commercial gain without recognizing their cultural heritage. Rituals and Traditions: Adopting or modifying cultural rituals and traditions without proper understanding or respect for their significance is another aspect of cultural appropriation. This can involve appropriating religious practices, ceremonies, or spiritual symbols without understanding their sacredness.

Iggy Azalea: The Australian rapper faced criticism for appropriating African American Vernacular English (AAVE) in her music and performances. Her adoption of African American culture and style drew accusations of cultural appropriation. Katy Perry: The pop singer has been accused of cultural appropriation for incorporating elements of various cultures, such as Japanese, Indian, and African, in her music videos and stage performances. Kylie Jenner: The reality TV star and entrepreneur faced backlash for appropriating Black culture through her hairstyles, such as wearing cornrows, which some viewed as a misappropriation of a traditionally African hairstyle. Marc Jacobs: The fashion designer faced criticism for featuring white models wearing dreadlocks on the runway, which was seen as cultural appropriation of a hairstyle deeply rooted in African and African American culture. Miley Cyrus: The singer and actress faced controversy for appropriating elements of Black culture, including twerking and adopting a hip-hop-inspired persona during her Bangerz era.

Power Dynamics: This theory emphasizes the power imbalances between dominant and marginalized cultures. It argues that cultural appropriation occurs when elements of a marginalized culture are adopted and commodified by the dominant culture without proper understanding or respect, perpetuating inequalities and erasing the cultural context. Appreciation vs. Appropriation: This theory distinguishes between cultural appreciation and cultural appropriation. It suggests that appreciation involves respectfully learning about and engaging with different cultures, while appropriation involves taking elements out of context, often for personal gain, without understanding or respecting their cultural significance. Commodification: This theory focuses on the commercial aspect of cultural appropriation. It highlights how cultural elements, such as fashion, music, or art, are often commodified and stripped of their original cultural meaning, resulting in the exploitation of marginalized cultures for profit. Cultural Exchange: This theory acknowledges that cultural borrowing and exchange have existed throughout history. It suggests that cultural exchange becomes problematic when it lacks mutual respect, consent, and acknowledgment of power dynamics, leading to the erasure or exploitation of the culture being borrowed from.

Borrowing Elements: Cultural appropriation involves the adoption or borrowing of cultural elements, including symbols, traditions, clothing, music, language, or rituals, from another culture. Power Imbalance: Cultural appropriation often occurs within a power dynamic where a dominant culture adopts elements from a marginalized culture. The dominant culture may hold more social, economic, or political power, resulting in the exploitation or erasure of the culture being appropriated. Lack of Understanding: Cultural appropriation often reflects a lack of understanding, knowledge, or respect for the cultural significance, history, and context of the borrowed elements. It can lead to misrepresentation, distortion, or trivialization of the original culture. Commercialization and Commodification: Cultural appropriation frequently involves the commodification and commercial exploitation of cultural elements, turning them into trendy fashion, consumer products, or entertainment without proper acknowledgment or compensation to the source culture. Harmful Stereotypes: Cultural appropriation can perpetuate harmful stereotypes, reinforce prejudices, or contribute to the marginalization and discrimination of the culture being appropriated. Absence of Consent and Recognition: Cultural appropriation occurs when elements are taken without the consent or involvement of the originating culture, often without giving credit or recognizing the contributions of the culture being appropriated.

Marginalization and Exploitation: Cultural appropriation can contribute to the marginalization and exploitation of marginalized communities. When elements of their culture are taken out of context or commodified without proper understanding or respect, it can perpetuate power imbalances and reinforce inequalities. Cultural Misrepresentation: Cultural appropriation can lead to misrepresentation and distortion of cultures. It can perpetuate stereotypes, misconceptions, and simplifications, reducing rich and diverse cultural practices to shallow and inaccurate portrayals. Erosion of Cultural Identity: When cultural elements are taken and divorced from their original context and meaning, it can erode the cultural identity and significance attached to them. This can lead to the loss of cultural heritage and the devaluation of traditions, rituals, and symbols. Appropriation vs. Appreciation: The influence of cultural appropriation highlights the need for a shift from appropriation to appreciation. It encourages a more respectful approach to cultural exchange that involves learning, understanding, and honoring the source culture's perspectives, histories, and contributions. Social Awareness and Activism: Cultural appropriation has fueled social awareness and activism. It has sparked discussions and movements that aim to challenge and address the harmful effects of appropriation, promote cultural sensitivity, and advocate for the rights of marginalized communities.

The topic of cultural appropriation is important to write an essay about due to its far-reaching implications and significance in today's diverse and interconnected world. Cultural appropriation raises critical questions about power dynamics, identity, representation, and social justice. By exploring this topic, one can delve into the complexities of cultural exchange, appreciation, and exploitation. Writing an essay on cultural appropriation allows for an examination of the historical context, current manifestations, and the impact it has on marginalized communities. It provides an opportunity to critically analyze the ethical, social, and cultural implications of borrowing elements from different cultures. The essay can delve into the importance of recognizing and respecting the origins, meanings, and value systems associated with cultural practices and artifacts. Moreover, addressing cultural appropriation fosters a deeper understanding of privilege, cultural sensitivity, and the need for cross-cultural dialogue. It encourages individuals to reflect on their own role in perpetuating or challenging appropriation, and prompts discussions on the responsibility of individuals and institutions in promoting cultural understanding and equity.

1. Alcoff, L. M. (2019). The problem of speaking for others. In The feminist standpoint theory reader: Intellectual and political controversies (pp. 210-222). Routledge. 2. Anderson, K. (2009). Cultural appropriation and the arts. Wiley-Blackwell. 3. Choo, H. Y., & Ferree, M. M. (2010). Practicing intersectionality in sociological research: A critical analysis of inclusions, interactions, and institutions in the study of inequalities. Sociological Theory, 28(2), 129-149. 4. Delgado, R., & Stefancic, J. (2017). Critical race theory: An introduction. New York University Press. 5. Hooks, B. (1992). Black looks: Race and representation. South End Press. 6. Lentin, A. (2008). Racism and anti-racism in Europe. Pluto Press. 7. Matthes, E. H. (2017). Cultural appropriation and the arts. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. 8. McLeod, J. (2017). The ethics of cultural appropriation. Wiley-Blackwell. 9. Richardson, J. E. (2019). (Mis)appropriation, hybridity, and resistance: Revisiting the cultural politics of rap music. In Popular culture and the civic imagination: Music, dissent, and social change (pp. 67-89). Routledge. 10. Young, R. (2008). Colonial desire: Hybridity in theory, culture, and race. Routledge.

Relevant topics

- Social Justice

- American Identity

- Media Analysis

- Discourse Community

- Sociological Imagination

- Sex, Gender and Sexuality

- Effects of Social Media

- Social Media

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is Cultural Appropriation?

Arlin Cuncic, MA, is the author of "Therapy in Focus: What to Expect from CBT for Social Anxiety Disorder" and "7 Weeks to Reduce Anxiety." She has a Master's degree in psychology.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/ArlinCuncic_1000-21af8749d2144aa0b0491c29319591c4.jpg)

Akeem Marsh, MD, is a board-certified child, adolescent, and adult psychiatrist who has dedicated his career to working with medically underserved communities.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/akeemmarsh_1000-d247c981705a46aba45acff9939ff8b0.jpg)

Verywell / Alison Czinkota

- Identification

Cultural appropriation refers to the use of objects or elements of a non-dominant culture in a way that reinforces stereotypes or contributes to oppression and doesn't respect their original meaning or give credit to their source. It also includes the unauthorized use of parts of their culture (their dress, dance, etc.) without permission.

In this way, cultural appropriation is a layered and nuanced phenomenon that many people may have trouble understanding and may not realize when they are doing it themselves.

It can be natural to merge and blend cultures as people from different backgrounds come together and interact. In fact, many wonderful inventions and creations have been born from the merging of such cultures (such as country music).

However, the line is drawn when a dominant cultural group makes use of elements of a non-dominant group in a way that the non-dominant group views as exploitative.

Cultural appropriation can be most easily recognized by asking this question of the non-dominant group: Does the use of this element of your culture in this way bother you?

Elements of Cultural Appropriation

Taking a step backward, how do we define cultural appropriation? It helps to consider what is meant by each of the terms in the phrase, as well as some related terms that are important to understand.

Culture refers to anything associated with a group of people based on their ethnicity, religion, geography, or social environment. This might include beliefs, traditions, language, objects, ideas, behaviors, customs, values, or institutions. It's not uncommon for culture to be thought of as belonging to particular ethnic groups.

Appropriation

Appropriation refers to taking something that doesn't belong to you or your culture. In the case of cultural appropriation, it is an exchange that happens when a dominant group takes or "borrows" something from a minority group that has historically been exploited or oppressed.

In this sense, appropriation involves a lack of understanding of or appreciation for the historical context that influences what is being taken. Taking a sacred object from a historically marginalized culture and producing it as part of a Halloween costume is one example.

Cultural Denigration

Cultural denigration is when someone adopts an element of a culture with the sole purpose of humiliating or putting down people of that culture. The most obvious example of this is blackface, which originated as a way to denigrate and dehumanize Black people by perpetuating negative stereotypes.

Cultural Appreciation & Respect

Cultural appreciation, on the other hand, is the respectful borrowing of elements from another culture with an interest in sharing ideas and diversifying oneself . Examples would include learning martial arts from an instructor with an understanding of the practice from a cultural perspective or eating Indian food at an authentic Indian restaurant.

When done correctly, cultural appreciation can result in deeper understanding and respect across cultures as well as creative hybrids that blend cultures together.

Dehumanizes oppressed groups

Takes without permission

Perpetuates stereotypes

Ignores the meaning and stories behind the cultural elements

Celebrates cultures in a respectful way

Asks permission, provides credit, and offers compensation

Elevates the voices and experiences of members of a cultural group

Focuses on learning the stories and meanings behind cultural elements

Types of Cultural Appropropriation

There are four main types of cultural appropriation:

- Exchange : This form is defined as a reciprocal exchange between two cultures that are approximately equal in terms of power and dominance.

- Dominance : This type involves a dominant culture taking elements of a subordinate culture that has had a dominant culture forced upon it.

- Exploitation : This type is defined as taking cultural elements of a subordinate culture without compensation, permission, or reciprocity.

- Transculturation : This form involves taking and combining elements of multiple cultures, making it difficult to identify and credit the original source.

Context of Cultural Appropriation

Learning about the context of cultural appropriation is important for understanding why it is a problem. While some might not think twice about adopting a style from another culture, for example, the group with which the style originated may have historical experiences that make the person's actions insensitive to the group's past and current experience.

For example, consider a White American wearing their hair in cornrows. While Black Americans have historically experienced discrimination because of protective hairstyles like cornrows, White Americans, as part of the dominant group in the U.S., can often "get away" with appropriating that same hairstyle and making it "trendy," all the while not understanding or acknowledging the experiences that contributed to its significance in Black culture in the first place.

Examples of Cultural Appropriation

When considering examples of cultural appropriation, it's helpful to look at the types of items that can be a target. They include:

- Clothing and fashion

- Decorations

- Intellectual property

- Religious symbols

- Wellness practices

In the United States, the groups that are most commonly targeted in terms of cultural appropriation include Black Americans, Asian Americans, Hispanic and Latinx Americans , and Native Americans.

The following are some real-world examples of cultural appropriation to consider.

Rock 'N' Roll

In the 1950s, White musicians "invented" rock and roll; however, the musical style was appropriated from Black musicians who never received credit. In fact, music executives at the time chose to promote White performers over Black performers, reinforcing the idea that cultural appropriation involves a negative impact on a non-dominant group.

Sweat Lodge

In 2011, motivational entrepreneur James Arthur Ray was convicted of three counts of negligent homicide after the death of three participants in his pseudo sweat lodge . This is an extreme example of the cultural appropriation and misrepresentation of Native American traditions.

Do you remember the "voguing" craze made popular by Madonna back in the 1990s? Voguing as a dance actually had its roots in the gay clubs of New York City and was pioneered by Black members of the LGBTQ+ community. Madonna defends her right to artistic expression, but the question remains—how many people still mistakenly think she invented voguing?

Team Mascots

There is a history of major sports teams in the United States and Canada being involved in the cultural appropriation of Indigenous cultures through their names and mascots. Past and present examples include the Chicago Blackhawks, Cleveland Indians, Washington Redskins, and Edmonton Eskimos. (The Redskins and Eskimos have since undergone name changes.)

"Redskin" is a derogatory term for Indigenous people, and the term "eskimo" has been rejected by the Inuit community.

How to Know If Something Is Cultural Appropriation

If you are unsure how to decide if something is cultural appropriation, here are some questions to ask yourself:

- What is your goal with what you are doing?

- Are you following a trend or exploring the history of a culture?

- Are you deliberately trying to insult someone's culture or are you being respectful?

- Are you purchasing something (e.g., artwork) that is a reproduction of a culture or an original?

- How would people from the culture you are borrowing from feel about what you are doing?

- Are there any stereotypes involved in what you are doing?

- Are you using a sacred item (e.g., headdress) in a flippant or fun way?

- Are you borrowing something from an ancient culture and pretending that it is new?

- Are you crediting the source or inspiration of what you are doing?

- If a person of the original culture were to do what you are doing, would they be viewed as "cool" or could they possibly face discrimination?

- Are you wearing a costume (e.g., Geisha girl, tribal wear) that represents a culture?

- Are you ignoring the cultural significance of something in favor of following a trend?

Explore these questions and always aim to show sensitivity when adopting elements from another culture. If you do realize that something you have done is wrong, accept it as a mistake and then work to change it and apologize for it .

If you aren't sure if something is considered cultural appropriation, you need to look no further than the reaction of the group from whom the cultural element was taken.

How to Avoid Cultural Appropriation

You can avoid cultural appropriation by taking a few steps, such as these:

- Ask yourself the list of questions above to begin to explore the underlying motivation for what you are doing.

- Give credit or recognize the origin of items that you borrow or promote from other cultures rather than claiming them as your original ideas.

- Take the time to learn about and truly appreciate a culture before you borrow or adopt elements of it. Learn from those who are members of the culture, visit venues they run (such as restaurants) and attend authentic events (such as going to a real luau).

- Support small businesses run by members of the culture rather than buying mass-produced items from big box stores that are made to represent a culture.

A Word From Verywell

Cultural appropriation is the social equivalent of plagiarism with an added dose of denigration. It's something to be avoided at all costs, and something to educate yourself about.

In addition to watching your own actions, it's important to be mindful of the actions of corporations and be choosy about how you spend your dollars as that is another way of supporting members of the non-dominant culture. Do what you can when you can as you learn to do better.

National Conference for Community and Justice. What is cultural appropriation? .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cultural competence in health and human services .

History. How the history of blackface is rooted in racism .

Rogers RA. From cultural exchange to transculturation: a review and reconceptualization of cultural appropriation . Commun Theory . 2006;16(4):474-503. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2006.00277.x

Penal MA. Blonde braids and cornrows: Cultural appropriation of black hairstyles . ResearchGate . 2020. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.30870.98885

Cherid M. "Ain't got enough money to pay me respect": Blackfishing, cultural appropriation, and the commodification of blackness . Cult Stud Critical Methodol . 2021;21(5):359-364. doi:10.1177/15327086211029357

Kleisath C. The costume of Shagri-La: Thoughts on white privilege, cultural appropriation, and anti-Asian racism . J Lesbian Stud . 2014;18:142-157. doi:10.1080/10894160.2014.849164

Fan Y. The identity of Pilsen—Spanish language presence, cultural appropriation, and gentrification . University of Chicago English Language Institute.

Reed T. Fair use as cultural appropriation. California Law Review.

Boxill-Clark C. In search of harmony in culture: An analysis of American rock music and the African American experience . Dominican University of California.

Harris D, Effron L. James Ray found guilty of negligent homicide in Arizona sweat lodge case . ABC News .

History. How 19th-century drag balls evolved into house balls, birthplace of voguing .

Sharrow E, Tarsi M, Nteta T. What's in a name? Symbolic racism, public opinion, and the controversy over the NFL's Washington Football team name . Race Social Prob . 2020;13:110-121. doi:10.1007/s12552-020-09305-0

Kaplan L. Inuit or eskimo: Which name to use? . Alaska Native Language Center.

National Institutes of Health. Cultural respect .

Thagard P. Cultural appropriation, appreciation, and denigration .

Williamson T. Yes, cultural appropriation can happen within the Indigenous community and yes, we should be debating it .

By Arlin Cuncic, MA Arlin Cuncic, MA, is the author of "Therapy in Focus: What to Expect from CBT for Social Anxiety Disorder" and "7 Weeks to Reduce Anxiety." She has a Master's degree in psychology.

Winter 2024

All Shook Up: The Politics of Cultural Appropriation

In the era of global capitalism, imagining the lives of others is a crucial form of solidarity.

I first heard the phrase “Stay in your lane” a few years ago, in a writing workshop I was teaching. We were talking about a story that a student in the group, an Asian-American man, had written about an African-American family.

There was a lot to criticize about the story, including an abundance of clichés about the lives of Black Americans. I had expected the class to offer suggestions for improvement. What I hadn’t expected was that some students would tell the writer that he shouldn’t have written the story at all. As one of them put it, if a member of a relatively privileged group writes a story about a member of a marginalized group, this is an act of cultural appropriation and therefore does harm.

Arguments about cultural appropriation make the news every month or two. Two women from Portland, after enjoying the food during a trip to Mexico, open a burrito cart when they return home but, assailed by online activists, close their business within months. A yoga class at a university in Canada is shut down by student protests. The author of a young-adult novel, criticized for writing about characters from backgrounds different from his own, apologizes and withdraws his book from circulation. Such a wide variety of acts and practices is condemned as cultural appropriation that it can be hard to tell what cultural appropriation is .

Much of the literature on cultural appropriation is spectacularly unhelpful on this score. LeRhonda S. Manigault-Bryant, a professor of Africana studies at Williams College, says that the term “refers to taking someone else’s culture—intellectual property, artifacts, style, art form, etc.—without permission.” Similarly, Susan Scafidi, a professor of law at Fordham and the author of Who Owns Culture? Appropriation and Authenticity in American Law , defines it as “Taking intellectual property, traditional knowledge, cultural expressions, or artifacts from someone else’s culture without permission. This can include unauthorized use of another culture’s dance, dress, music, language, folklore, cuisine, traditional medicine, religious symbols, etc.”

These definitions seem enlightening, until you think about them. For one thing, the idea of “taking” something from another culture is so broad as to be incoherent: there’s nothing in these definitions that would prevent us from condemning someone for learning another language. For another, they rely on an idea—“permission”—that doesn’t, in this context, have any meaning.

Permission to use another group’s cultural expressions isn’t something that it’s possible to receive, because ethnicities, gender identities, and other such groups don’t have representatives authorized to grant it. When novelists, for example, write outside their own experience, publishing houses now routinely enlist “sensitivity readers” to make sure they say nothing that will offend—but once the books are published, novelists are on their own. There’s nothing they can do to rebut the accusation that the products of their imagination were “unauthorized,” nothing they can do to ward off the charge that they’ve caused harm by straying outside their lanes.

Something like the admonition to stay in one’s lane lay behind the protests that arose when Dana Schutz’s portrait of Emmett Till in his casket was displayed in an exhibit at the Whitney Museum in 2017—probably the most acrimonious chapter of the cultural appropriation discussion in recent memory. The artist Hannah Black wrote an open letter to the Whitney “with the urgent recommendation that the painting be destroyed.” Black continued: “Through his mother’s courage, Till was made available to Black people as an inspiration and warning. Non-Black people must accept that they will never embody and cannot understand this gesture. . . .”

Schutz’s response identified the problem with the idea of staying in one’s lane. “I don’t know what it is like to be black in America,” she said,

but I do know what it is like to be a mother. Emmett was Mamie Till’s only son. The thought of anything happening to your child is beyond comprehension. Their pain is your pain. My engagement with this image was through empathy with his mother. . . . Art can be a space for empathy, a vehicle for connection. I don’t believe that people can ever really know what it is like to be someone else (I will never know the fear that black parents may have) but neither are we all completely unknowable.

She was saying that the lane that she shared with Mamie Till-Mobley by virtue of being a mother was just as salient as the lane of race.

A similar point was made by the political scientist Adolph Reed, in an article that highlighted the many ways in which the history of Black Americans and white Americans have been intertwined. Reed remarked that “one might argue that Schutz, as an American, has a stronger claim than [the British-born] Black to interpret the Till story. After all, the segregationist Southern order and the struggle against that order, which gave Till’s fate its broader social and political significance, were historically specific moments of a distinctively American experience.”

When Till-Mobley defied the authorities by displaying her son’s mutilated body in an open coffin, it was not with the aim of making his image available only for Black people. Till-Mobley said that “They had to see what I had seen. The whole nation had to bear witness to this.” The author Christopher Benson, who co-authored Death of Innocence: The Story of the Hate Crime that Changed America with Till-Mobley, wrote that “She welcomed the megaphone effect of a wider audience reached by multiple storytellers, irrespective of race: Bob Dylan’s song ‘Ballad of Emmett Till’; Gwendolyn Brooks’s poem ‘The Last Quatrain of the Ballad of Emmett Till’; James Baldwin’s play Blues for Mister Charlie ; Bebe Moore Campbell’s novel Your Blues Ain’t Like Mine ; and Rod Serling’s numerous interpretations in his TV shows, including The Twilight Zone .”

In writing about cultural appropriation in art, then, the point isn’t that artists should be permitted to imagine the experiences of others as long as they can establish that they share a lane. There are no two people on the planet who don’t share a few lanes. The point is that artists imagine the experiences of others by virtue of a common humanity.

A common humanity: the phrase seems quaint, anachronistic, even as I type it. But I think the restoration of the dignity and prestige of the idea is one of the tasks of the contemporary left.

In the world of fiction—the area of artistic endeavor that I know best—imagining other lives is part of the job.

The philosopher and novelist Iris Murdoch wrote, “We judge the great novelists by the quality of their awareness of others.” If Tolstoy is considered by many to be the greatest novelist who ever lived, this isn’t because of the beauty of his sentences or the shapeliness of his plots. It’s because he could bring to life so many wildly different characters, from the young girl preparing eagerly for her first ball to the old man dying in his bed, from the aristocrat on a foxhunt to the serf watching the aristocrat ride by. Tolstoy’s intense responsiveness to life jolts us into an awareness of how much more deeply we could be living; his intense responsiveness, in particular, to other people, jolts us into an awareness of how much more keenly we could be entering into the experiences of the people around us.

One of Tolstoy’s contemporaries, George Eliot, wrote explicitly about the effort to imagine the minds of others as a sort of moral necessity. In Middlemarch , Eliot introduces us to a vibrant young woman, Dorothea Brooke, who is about to marry a desiccated scholar named Casaubon. Dorothea naively believes that Casaubon is a man of great intellect and great humanity; everyone else who knows them sees what she can’t see: that she’s about to marry a cold, humorless, ungenerous man.

Around seventy-five pages into the novel, Eliot does a remarkable thing. She stops the action and says, in effect, we’ve heard what everyone else thinks of Casaubon, but what does Casaubon think about himself?

Suppose we turn from outside estimates of a man, to wonder, with keener interest, what is the report of his own consciousness about his doings or capacity: with what hindrances he is carrying on his daily labours; what fading of hopes, or what deeper fixity of self-delusion the years are marking off within him; and with what spirit he wrestles against universal pressure, which will one day be too heavy for him, and bring his heart to its final pause. Doubtless his lot is important in his own eyes; and the chief reason that we think he asks too large a place in our consideration must be our want of room for him. . . . Mr. Casaubon, too, was the centre of his own world. . . .

This little passage is one of the most beautiful statements of the novelist’s creed that I know. Everyone is the center of a world. The novelist’s work is to honor this truth, and one of the ways in which a novelist does so is to imagine what it is to live in other people’s skin.

A common objection to sentiments like this holds that the freedom to imagine other lives has long been held almost exclusively by white writers, who have abused the freedom by creating inaccurate and demeaning images of others, and that it’s therefore especially important for white writers to stay in their lane. In this account, silence is recommended as a form of collective penance.

The novelist Kamila Shamsie has answered this argument thoughtfully. She writes that there is

something deeply damaging in the idea that writers couldn’t take on stories about the Other. As a South Asian who has encountered more than her fair share of awful stereotypes about South Asians in the British empire novels of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, I’m certainly not about to disagree with the charge that writers who are implicated in certain power structures have been guilty of writing fiction which supports, justifies and props up those power structures. I understand the concerns of people who feel that for too long stories have been told about them rather than by them. But it should be clear that the response to this is for writers to write differently, to write better. . . . The moment you say, a male American writer can’t write about a female Pakistani, you are saying, Don’t tell those stories. Worse, you’re saying, as an American male you can’t understand a Pakistani woman. She is enigmatic, inscrutable, unknowable. She’s other. Leave her and her nation to its Otherness.

Although it’s not uncommon to hear people say that writing from the point of view of someone outside one’s “identity group” is never permissible, critics and reviewers seem to have reached a softer consensus about the subject. They tend to say that fiction writers should of course claim the freedom to imagine the interior lives of others, but they must do so “responsibly.”

On one level, this is obviously reasonable. If someone wrote a story about a devout Muslim with a scene in which the main character came home from work and made himself a pork chop, it would be reasonable to tell the writer that he needed to find out a little more about Islamic customs and beliefs, and it would be reasonable to tell him to approach the subject more responsibly.

But if we think about it, this notion of responsibility has disquieting implications.

Isaac Babel, the great Russian-Jewish short story writer, published most of his work before the Stalin regime came to power. After Stalin began to imprison and execute writers and intellectuals, Babel tried to stay alive by staying silent. But even while he tried to display his allegiance to the regime, he couldn’t suppress his independence of mind. At a writers’ conference in Moscow in 1934, Babel said that “the party and government have given us everything and have taken from us only one right—that of writing badly. Comrades, let’s be honest, this was a very important right and not a little is being taken from us.”

Babel was saying that Stalin had taken away everything. Without the freedom to write badly, the writer has no freedom at all.

Just as writers need the freedom to write badly, they need the freedom to write irresponsibly. The best fiction is deeply moral—George Eliot’s creed of empathy is the highest ethical idea I can conceive of—and yet fiction couldn’t be written at all if it lost its connection to the world of irresponsible play.

After the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini proclaimed a fatwa against Salman Rushdie for publishing The Satanic Verses , some writers and intellectuals expressed their solidarity with Rushdie, while others murmured that he should have written more responsibly. Without admitting it to themselves, they were standing with his persecutors, implying that he brought the fatwa down upon himself through his provocative literary behavior. The right to offend, the right to satirize, even the right to get things wrong—all of these are precious, and anyone who believes oneself a friend of art and literature needs to defend them without qualification.

I should make it clear that I’m not saying that people who grouse about cultural appropriation are as bad as Stalin or the Ayatollah. I’m saying they don’t respect the anarchic energies of art.

When Diaghilev commissioned Jean Cocteau to write the libretto for one of his ballets, his only words of instruction were, “Astonish me!” What young artists today are being told is something more along the lines of “Watch your step!”

Just as the critics of cultural appropriation have a puritanical view of art, they have a puritanical view of culture as well. Let’s look again at Susan Scafidi’s definition: “Taking intellectual property, traditional knowledge, cultural expressions, or artifacts from someone else’s culture without permission. This can include unauthorized use of another culture’s dance, dress, music, language, folklore, cuisine, traditional medicine, religious symbols, etc.”

We imagine the arbiter of cultural appropriation as a kindergarten teacher, sternly telling the children not to use one another’s toys without asking. But this isn’t the way culture develops. There is no product of culture that isn’t the result of mixing—that isn’t the result of taking things without permission—from the meals we make to the music we enjoy to the language that I’m using to write this essay.

Much of the mixing has been on horribly unequal terms. But not all of it. In our current way of looking at it, cultural appropriation is always pictured as a vampire-like dominant culture draining the blood of a minority culture too weak to defend itself. A more confident social justice movement might see some of these borrowings as evidence of the strength of popular creativity. Ralph Ellison, in a review of a book about music and race in America, was getting at this idea when he wrote of the origins of the blues as “enslaved and politically weak men successfully imposing their values upon a powerful society through song. . . .”

In many of his essays, written as far back as sixty years ago, Ellison turns out to be one of the surest guides to the controversies around cultural appropriation that we have. Here he is in his essay “The Little Man at Chehaw Station”:

It is here, on the level of culture . . . that elements of the many available tastes, traditions, ways of life, and values that make up the total culture have been ceaselessly appropriated and made their own—consciously, unselfconsciously, or imperialistically—by groups and individuals to whose own backgrounds and traditions they are historically alien. Indeed, it was through this process of cultural appropriation (and misappropriation) that Englishmen, Europeans, Africans, and Asians became Americans. The Pilgrims began by appropriating the agricultural, military and meteorological lore of the Indians, including much of their terminology. The Africans, thrown together from numerous ravaged tribes, took up the English language and the biblical legends of the ancient Hebrews and were “Americanizing” themselves long before the American Revolution. . . . Everyone played the appropriation game. . . . Americans seem to have sensed intuitively that the possibility of enriching the individual self by such pragmatic and opportunistic appropriations has constituted one of the most precious of their many freedoms. . . . [I]n this country things are always all shook up, so that people are constantly moving around and rubbing off on one another culturally.

Ellison’s friend and comrade-in-arms Albert Murray had a similar perspective. “American culture,” he wrote, “even in its most rigidly segregated precincts, is patently and irrevocably composite. . . . Indeed, for all their traditional antagonisms and obvious differences, the so-called black and so-called white people of the United States resemble nobody else in the world so much as they resemble each other.”

After you spend time reading Ellison and Murray, critics of cultural appropriation begin to seem like members of a weird purity cult, issuing edicts and prohibitions against the kinds of mixing that are an inevitable part of life.

For an eloquent and lively example of a viewpoint largely opposed to the one I’m expressing here, I’d recommend Lauren Michele Jackson’s White Negroes: When Cornrows Were in Vogue . . . And Other Thoughts on Cultural Appropriation . Jackson writes with wit and gusto about these issues, at times sounding like an observer in the tradition of Ellison and Murray. “Appropriation is everywhere, and is also inevitable. . . . The idea that any artistic or cultural practice is closed off to outsiders at any point in time is ridiculous, especially in the age of the internet.”

But although much of her book celebrates this kind of mingling, when she considers examples of white artists who are influenced by Black culture, she tends to find the consequences malign. “When the powerful appropriate from the oppressed,” she writes, “society’s imbalances are exacerbated and inequalities prolonged. In America, white people hoard power like Hungry Hungry Hippos. In the history of problematic appropriation in America, we could start with the land and crops commandeered from Native peoples along with the mass expropriation of the labor of the enslaved. The tradition lives on. The things black people make with their hands and minds, for pay and for the hell of it, are exploited by companies and individuals who offer next to nothing in return.”

But if the practice of cultural mingling, as Jackson so vividly demonstrates, is as natural and inevitable as breathing, it can’t be the practice itself that’s the cause of the inequalities she rightly condemns. The causes must lie elsewhere.

Listen to the historian Barbara J. Fields:

Everybody inhabits many [cultures], all simultaneous, all overlapping. It was true for Chuck Berry and Elvis Presley, and it is true for us today, sharing a history beyond our individual experience and therefore sharing the culture that history has produced. Differences of political standing and economic power ensure that some people can monetize a shared cultural inheritance more than others, just as some enjoy greater wealth and higher incomes, live in better housing, receive better educations, and live longer and healthier lives. But that is because of political and economic exploitation, not cultural appropriation. . . . [P]olitical action, not cultural policing, is needed to tackle it.

It makes little sense to condemn an artist or entertainer for taking something from another population on unequal terms while failing to note that all of us—anyone who might read Lauren Michele Jackson’s book, anyone who might read this essay—are doing the same thing during every moment of our lives. In a globalized capitalist economy, every object we buy or use or wear or touch is likely to have been made by workers without significant labor rights in faraway places.

The way forward isn’t to pursue a dream of staying within our lanes. (Stop wearing clothes! Stop using phones! Stop eating food you didn’t grow yourself!) The only way forward is for those of us who are not among the one percent to make common cause in order to put an end to these inequities.

The more one reads about cultural appropriation, the more difficult it is to resist the conclusion that the preoccupation with staying in your lane is a sort of counterfeit politics.

Critics of cultural appropriation believe themselves to be involved in a significant political activity, yet the objects of their criticism are usually people who are relatively powerless—the yoga teacher, the women with the burrito cart, the visual artist, the novelist who dares to venture out of her lane. It would be hard to make the case that the critique of cultural appropriation constitutes an assault on unjust hierarchies in our society, since those who hold real power are rarely the objects of this critique.

Charges of cultural appropriation are also often made against successful artists and celebrities, from Elvis Presley to Kim Kardashian to Jeanine Cummins, the author of American Dirt —but it would be fanciful to say that entertainers represent the source of power and unjust hierarchy in our society either.

In 2013, the internet spent a few minutes mulling over the question of whether the band Arcade Fire was guilty of cultural appropriation when it put out the album Reflektor , which was heavily influenced by the music of Haiti. It wasn’t a major controversy, as internet controversies go, but it was significant enough to make its way to the pages of the Atlantic . (Finally, most of the people who discussed this were willing to give the band a pass, since its frontman, Win Butler, had been immersed in the music of Haiti for years, and his wife and bandmate, Régine Chassagne, is of Haitian descent.)

Not too long before this, ordinary Haitians had endured a different form of appropriation, a form that went unremarked upon by those who were pondering the question of how much disapproval to express toward Arcade Fire.

In 2009, Haiti’s parliament raised the national minimum wage to 61 cents an hour. Foreign manufacturers, along with the U.S. State Department, immediately pushed back, prevailing on Haiti to lower textile workers’ minimum wage to 31 cents an hour. This came to about $2.50 per day, in a country whose estimated daily cost of living for a family of three was about $12.50.

Powerful corporations from the most powerful country on earth exerted pressure that intensified the destitution of people in Haiti. Among the corporations were Levi Strauss and Hanes, whose CEO was at that time receiving a compensation package of about $10 million a year. Yet you could have searched Facebook and Twitter and the rest of the internet for a long time before finding any Americans who cared or even knew about any of this, even after WikiLeaks and the Nation brought it to light in 2011.

In 2017, the two Portland women who’d opened a burrito cart closed their business after being assailed by online activists for appropriating the cuisine of Mexico. The following year, when the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company fired dozens of workers who were trying to launch an independent trade union at its factory in San Luis Potosí, Mexico, few in the world of online outrage took any notice.

Of course, the pressure exerted on working people in Haiti and Mexico is the same pressure that corporate power exerts all over the world, including within this country, where capital’s long war against labor rights and social welfare provisions seems to grow more intense every year. This is true appropriation—the stealing of people’s life chances, the repression of their opportunity for leisure and health and safety, the bulldozing of any possibility of equitable local development. The malefactors here aren’t women running a burrito cart or musicians soaking up influences or white models wearing dreadlocks or writers trying to dream their way into other people’s lives, but corporate actors making decisions that degrade us all.

Sometimes I wish we were equipped with an extra sense, a sense that would allow us to perceive how connected we are to one another. When I put on my shirt, I would feel the labor of the garment worker in Nicaragua who pieced it together; when I use my phone, I would be aware of the child laborer in the Democratic Republic of the Congo who mined the cobalt for its battery; when I peel an orange, I would feel the presence of the worker in Florida who picked it.

Lacking such a sense, we need to cultivate the sympathetic imagination. We need to try to imagine the lives of others.

So I’m not finally arguing that when artists try to imagine the lives of others, we should lighten up and see their efforts as basically harmless. I’m arguing that imagining the lives of others is an essential part of the effort to bring into being a more human world.

We can embrace a sort of cultural solipsism that holds that different groups have nothing in common, or we can understand that our lives are inextricably bound up with the lives of people we’ll never know. We can deny what we owe to one another, or we can seek to retrieve the vision of a shared humanity. We can choose to believe that it’s virtuous to try to stay in our lanes, or we can choose to learn about the idea of solidarity. It’s an old idea, but for those of us concerned with freedom and equality, it’s still the best idea we have.

Brian Morton ’s novels include Starting Out in the Evening and Florence Gordon .

Sign up for the Dissent newsletter:

Socialist thought provides us with an imaginative and moral horizon.

For insights and analysis from the longest-running democratic socialist magazine in the United States, sign up for our newsletter:

Cultural appropriation and oppression

- Published: 17 December 2018

- Volume 176 , pages 1003–1013, ( 2019 )

Cite this article

- Erich Hatala Matthes 1

15k Accesses

35 Citations

Explore all metrics

In this paper, I present an outline of the oppression account of cultural appropriation and argue that it offers the best explanation for the wrongfulness of the varied and complex cases of appropriation to which people often object. I then compare the oppression account with the intimacy account defended by C. Thi Nguyen and Matt Strohl. Though I believe that Nguyen and Strohl’s account offers important insight into an essential dimension of the cultural appropriation debate, I argue that justified objections to cultural appropriation must ultimately be grounded in considerations of oppression as opposed to group intimacy. I present three primary objections to the intimacy account. First, I suggest that in its effort to explain expressive appropriation claims (those that purportedly lack an independent ground), the intimacy account doubles down on the boundary problem. Second, I question whether group intimacy possess the kind of bare normativity that Nguyen and Strohl claim for it. Finally, I argue that these objections give us reason to accept the importance of group intimacy to the cultural appropriation debate, but question the source of its significance as identified by Nguyen and Strohl.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Cultural appropriation and the intimacy of groups

C. Thi Nguyen & Matthew Strohl

Cultural appropriation: an Husserlian account

Molly Brigid McGrath

Cultural Competence, Identity Politics, and the Utopian Dilemma

I follow Young ( 2011 ) in adopting a pluralistic understanding of oppression.

For a more detailed overview of these and other issues related to cultural appropriation, please see Matthes ( 2018 ).

Though it is worth noting that the idea of cultural property itself need not (and, I’ve argued, ought not) be understood in a depoliticized, universalist sense either (Matthes 2017 ).

For a broader discussion of gendered behavioral control, see Manne ( 2017 ).

For an interesting example of appropriation used as a tool to combat oppression, see Walsh and Lopes ( 2012 ). Even in this case, though, it’s not clear that the appropriation challenges the dominant group’s autonomy per se.

Compare with the idea that we should repatriate material culture to former colonies independently of their claim to any particular item, but rather, as an act of recognition and redress for the undermining of their autonomy (Ypi 2013 ; Matthes 2017 ).

Appiah, K. A. (2006). Whose culture is it, anyway? In Cosmopolitanism (pp. 115–135). New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Coombe, R. J. (1993). The properties of culture and the politics of possessing identity: Native claims in the cultural appropriation controversy. Canadian Journal of Law and Jurisprudence, VI (2), 249–285.

Article Google Scholar

Cooper, B. (2015). Iggy Azalea’s post-racial mess: America’s oldest race tale, remixed. Salon . https://www.salon.com/2014/07/15/iggy_azaleas_post_racial_mess_americas_oldest_race_tale_remixed/ .

Dotson, K. (2011). Tracking epistemic violence, tracking practices of silencing. Hypatia, 26 (2), 236–257.

Fricker, M. (2007). Epistemic injustice . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Hladki, J. (1994). Problematizing the issue of cultural appropriation. Alternate Routes, 11, 95–119.

Google Scholar

Hurka, T. (1999). Should Whites write about minorities? In Principles: Short essays on ethics (2nd ed.). Toronto: Harcourt Brace.

Keeshig-Tobias, L. (1990). The magic of others. In L. Scheier, S. Sheard, & E. Wachtel (Eds.), Language in her eye: Views on writing and gender by Canadian women writing in English . Toronto: Coach House Press.

Killmister, S. (2011). Group-differentiated rights and the problem of membership. Social Theory and Practice, 37 (2), 227–255.

Liberto, H. (2014). Exploitation and the vulnerability clause. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, 17, 619–629.

Manne, K. (2017). Down girl: The logic of misogyny . New York: Oxford University Press.

Matthes, E. H. (2016). Cultural appropriation without cultural essentialism? Social Theory and Practice, 42 (2), 343–366.

Matthes, E. H. (2017). Repatriation and the radical redistribution of art. Ergo, 4 (32), 931–953.

Matthes, E. H. (2018). The ethics of cultural heritage. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy . https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ethics-cultural-heritage/ .

Mezey, N. (2007). The paradoxes of cultural property. Columbia Law Review, 107, 2004–2046.

Patten, A. (2014). Equal recognition: The moral foundations of minority rights . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rogers, R. A. (2006). From cultural exchange to transculturation: A review and reconceptualization of cultural appropriation. Communication Theory, 16, 474–503.

Shelby, T. (2002). Foundations of black solidarity: Collective identity or common oppression? Ethics, 112 (2), 231–266.

Todd, L. (1990). Notes on appropriation. Parallelogramme, 16 (1), 24–33.

Todd, L. (1992). What more do they want? In G. McMaster & L.-A. Martin (Eds.), Indigena: Contemporary native perspectives in Canadian art . Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre.

Valdman, M. (2009). A theory of wrongful exploitation. Philosophers’ Imprint, 9 (6), 1–14.

Walsh, A. N., & Lopes, D. M. (2012). Objects of appropriation. In J. O. Young & C. G. Brunk (Eds.), The ethics of cultural appropriation (pp. 211–234). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Young, J. O. (2005). Profound offense and cultural appropriation. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 63 (2), 135–146.

Young, J. O. (2008). Cultural appropriation in the arts . Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Young, I. M. (2011). Five faces of oppression. In Justice and the politics of difference . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Ypi, L. (2013). What’s wrong with colonialism. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 41 (2), 158–191.

Ziff, B., & Rao, P. V. (Eds.). (1997). Borrowed power . New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Download references

Acknowledgements

This paper has benefited from helpful discussions with Shen-yi Liao, Nick Riggle, Thi Nguyen, Matt Strohl, and audience members at the 2018 APA Pacific Division meeting in San Diego. Special thanks to Dominic McIver Lopes and Margaret Moore. Some parts of this paper were further developed in blog posts at Aesthetics for Birds : thanks to Alex King for feedback and providing an excellent venue for work in aesthetics. Thanks always to Jackie Hatala Matthes.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

324 Founders Hall, Wellesley College, 106 Central St, Wellesley, MA, 02481, USA

Erich Hatala Matthes

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Erich Hatala Matthes .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Matthes, E.H. Cultural appropriation and oppression. Philos Stud 176 , 1003–1013 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-018-1224-2

Download citation

Published : 17 December 2018

Issue Date : 15 April 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-018-1224-2

Article Contents

Theoretical development, self-authorization to consume cultural difference, data collection information, author notes.

- < Previous

Between Cultural Appreciation and Cultural Appropriation: Self-Authorizing the Consumption of Cultural Difference

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Angela Gracia B Cruz, Yuri Seo, Daiane Scaraboto, Between Cultural Appreciation and Cultural Appropriation: Self-Authorizing the Consumption of Cultural Difference, Journal of Consumer Research , Volume 50, Issue 5, February 2024, Pages 962–984, https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucad022

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Countervailing discourses of cultural appreciation versus cultural appropriation are fueling a tension between the ethnic consumer subject, who views the consumption of cultural difference as a valorized identity project, and the responsibilized consumer subject, who is tasked with considering the societal impacts of such consumption. Drawing on an extended qualitative investigation of international K-pop consumers, this study illustrates that this tension spurs consumers to pursue self-authorization—the reflexive reconfiguration of the self in relation to the social world—through which consumers grant themselves permission to continue consuming cultural difference. Four consumer self-authorization strategies are identified: reforming, restraining, recontextualizing, and rationalizing. Each strategy relies upon an amalgam of countervailing moral interpretations about acts of consuming difference, informing ideologies about the power relationships between cultures, and emergent subject positions that situate the consuming self in relation to others whose differences are packaged for consumption. Findings show notable conditions under which each self-authorization strategy is deployed, alongside consumers’ capacity to adjust and recombine different strategies as they navigate changing sociocultural and idiographic conditions. Overall, this study advances understanding of how consumers navigate the resurgent politics of marketized cultural diversity in an era of woke capitalism.

“Based on my experience, sometimes I see something as cultural appreciation, sometimes I see something as cultural appropriation. It really depends on the exact situations that I have been in. […] As an Asian American, seeing K-pop fans in America, I see it as cultural appreciation; on the flip side, when I see Koreaboos who use Korean names just for the fun of it, I see it as cultural appropriation because my name has been made fun of before.” (Sam, Reddit thread, September 2020)

The consumption of cultural difference refers to the market-mediated creation of desirable contrasts to everyday life and mainstream notions of identity using another culture’s objects, symbols, styles, motifs, and subjects ( Peñaloza 2001 ; Schroeder 2015 ; Young and Brunk 2009 ). For the past decades, a prevailing ideology of neoliberal multiculturalism suited to the demands of transnational capitalism institutionalized a desire to appreciate cultural difference as a valorized consumer identity project ( Coskuner-Balli and Ertimur 2017 ; Thompson and Tambyah 1999 ; Veresiu and Giesler 2018) . This prevailing discourse of cultural appreciation constitutes the ethnic consumer subject, who is hailed to “embrace differences through consumption” ( Veresiu and Giesler 2018 , 556). However, as Sam’s quote illustrates, a fairly recent change is emerging in popular understandings of this consumption domain. More and more, the consumer appreciation of cultural difference is being challenged by a countervailing set of ideas: the discourse of cultural appropriation that constitutes the responsibilized consumer subject.

Cultural appropriation refers to the use of elements of one culture by members of another culture, in ways that are perceived as unacknowledged or inappropriate ( Young and Brunk 2009 ; Ziff and Rao 1997 ). Although scholars have long problematized complex cultural inequities that surface when other, often marginalized, cultures are transformed into palatable sources of consumable difference ( hooks 2006 ; Peñaloza 2001 ; Root 1996 ; Skrbis and Woodward 2007 ; Veresiu and Giesler 2018 ), these critiques have only recently filtered into more pervasive public discussions and emerged as a significant concern for consumers ( Finkelstein and Rios 2022 ; Mosley and Biernat 2021 ; web appendix A ). In a sociocultural zeitgeist politicized through the lens of “wokeness” and “cancel culture” ( Kanai and Gill 2020) , consumers are hailed as responsibilized consumer subjects ( Giesler and Veresiu 2014 )—exhorted to take responsibility for how their actions intersect with issues of cultural diversity, equity, and inclusion ( Arsel, Crockett, and Scott 2022 ; Bajde and Rojas-Gaviria 2021 ; Giesler and Veresiu 2014 ; Gonzalez-Arcos et al. 2021 ). Consequently, the “Western neoliberal idyll of market-based inclusion and diversity” ( Veresiu and Giesler 2018 , 554) that calls the ethnic consumer subject to appreciate other cultures is being undercut by this countervailing discourse that calls the responsibilized consumer subject to engage with issues of cultural appropriation. Against this backdrop, an important question requires attention: how do consumers manage the tension between cultural appreciation and cultural appropriation when they pursue the consumption of cultural difference?

To address this question, we conducted a 6-year qualitative study of international (non-Korean) fans of Korean pop (K-pop). Through our time in the field, we observed vibrant consumer discussions of a tension between the competing discourses of cultural appreciation versus cultural appropriation. The theoretical lens of reflexivity, which holds that individuals are tasked with the adaptive construction of their own identities in relation to a systemically uncertain social world ( Adams and Raisborough 2008 ; Akaka and Schau 2019 ; Thompson, Henry, and Bardhi 2018) , provided a starting point for analyzing consumer discussions. This approach led us to identify consumer self-authorization, defined in our work as the reflexive reconfiguration of the self in relation to the social world through which consumers grant themselves permission to continue consuming cultural difference when confronting an identity-relevant tension between the ethnic consumer subject and the responsibilized consumer subject. We describe four consumer self-authorization strategies: reforming, restraining, recontextualizing, and rationalizing. Each strategy represents a distinct configuration of understandings of the self in relation to the social world aimed at conferring permission for oneself to continue consuming another culture’s elements.

Our theoretical account of consumer self-authorization illustrates how individuals carve diverse pathways through a tension that sits at the heart of consuming cultural difference. Inscribed in a nexus of countervailing discourses embedded in divergent ideologies of multiculturalism and hailing oppositional versions of consumer subjectivity, we find that consumers pursue diverse routes to craft permission to consume cultural difference while configuring who they are in relation to multiple others. Ultimately, however, consumer self-authorization is not aimed at radically dismantling systemic inequalities that continue to disadvantage people of color and people from the Global South. Instead, it constitutes an attempt to manage the tension between cultural appreciation and appropriation at the level of the individual consumer subject, carrying a broad range of consequences for how cultural difference is animated as a valued market resource.

The consumption of cultural difference is located at a nexus of two countervailing discourses. A cultural appreciation discourse frames the “making one’s own” of another culture’s elements ( Young and Brunk 2009 ) as an unproblematic process of cultural diffusion and blending. By contrast, a cultural appropriation discourse frames the “taking” of elements from another culture in problematic terms ( Ziff and Rao 1997 )—as a harmful act of distortion, decontextualization, and domination. Each discourse comprises three interwoven elements that sustain one another: a set of ideological assumptions about the power relationships between cultures, a moral interpretation about acts of consuming difference, and a vision of the ideal consumer subject ( table 1 ). Taken together, these countervailing discourses constitute a tension between cultural appreciation and cultural appropriation that has filtered into popular media and public debates ( Mosley and Biernat 2021 ), offering individuals varied interpretive resources to understand acts of consuming cultural difference.

CONSUMING CULTURAL DIFFERENCE: TWO COUNTERVAILING DISCOURSES

Cultural Appreciation Discourse and the Ethnic Consumer Subject