20th Century: Impressionism, Expressionism, & Twelve-Tone

Music of the 20th century.

Let’s begin the study of our final historical period with an overview of major trends and composers from the era. As you read this page, please pay special attention to the fact that this description focuses on compositional techniques and very little is said about dominant genres. The 20th century was clearly a period of widespread experimentation and many composers wanted the freedom to explore new compositional approaches without the restrictions and expectations that accompany traditional genres. Even when longstanding genres were used, composers felt very comfortable abandoning the traditional structures of those genres.

At the turn of the century, music was characteristically late Romantic in style. Composers such as Gustav Mahler, Richard Strauss and Jean Sibelius were pushing the bounds of Post-Romantic Symphonic writing. At the same time, the Impressionist movement, spearheaded by Claude Debussy, was being developed in France. The term was actually loathed by Debussy: “I am trying to do ‘something different—in a way realities—what the imbeciles call ‘impressionism’ is a term which is as poorly used as possible, particularly by art critics”—and Maurice Ravel’s music, also often labelled with this term, explores music in many styles not always related to it (see the discussion on Neoclassicism, below).

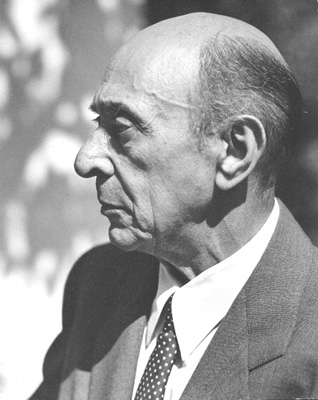

Figure 1. Arnold Schoenberg, Los Angeles, 1948

Many composers reacted to the Post-Romantic and Impressionist styles and moved in quite different directions. The single most important moment in defining the course of music throughout the century was the widespread break with traditional tonality, effected in diverse ways by different composers in the first decade of the century. From this sprang an unprecedented “linguistic plurality” of styles, techniques, and expression. In Vienna, Arnold Schoenberg developed atonality, out of the expressionism that arose in the early part of the 20th century. He later developed the twelve-tone technique which was developed further by his disciples Alban Berg and Anton Webern; later composers (including Pierre Boulez) developed it further still. Stravinsky (in his last works) explored twelve-tone technique, too, as did many other composers; indeed, even Scott Bradley used the technique in his scores for the Tom and Jerry cartoons.

After the First World War, many composers started returning to the past for inspiration and wrote works that draw elements (form, harmony, melody, structure) from it. This type of music thus became labelled neoclassicism. Igor Stravinsky ( Pulcinella and Symphony of Psalms ), Sergei Prokofiev ( Classical Symphony ), Ravel ( Le tombeau de Couperin ) and Paul Hindemith ( Symphony: Mathis der Maler ) all produced neoclassical works.

Figure 2. Igor Stravinsky

Italian composers such as Francesco Balilla Pratella and Luigi Russolo developed musical Futurism. This style often tried to recreate everyday sounds and place them in a “Futurist” context. The “Machine Music” of George Antheil (starting with his Second Sonata, “The Airplane”) and Alexander Mosolov (most notoriously his Iron Foundry ) developed out of this. The process of extending musical vocabulary by exploring all available tones was pushed further by the use of Microtones in works by Charles Ives, Julián Carrillo, Alois Hába, John Foulds, Ivan Wyschnegradsky, and Mildred Couper among many others. Microtones are those intervals that are smaller than asemitone; human voices and unfretted strings can easily produce them by going in between the “normal” notes, but other instruments will have more difficulty—the piano and organ have no way of producing them at all, aside from retuning and/or major reconstruction.

In the 1940s and 50s composers, notably Pierre Schaeffer, started to explore the application of technology to music in musique concrète. The term electroacoustic music was later coined to include all forms of music involving magnetic tape, computers, synthesizers, multimedia, and other electronic devices and techniques. Live electronic music uses live electronic sounds within a performance (as opposed to preprocessed sounds that are overdubbed during a performance), Cage’s Cartridge Music being an early example. Spectral music (Gérard Grisey and Tristan Murail) is a further development of electroacoustic music that uses analyses of sound spectra to create music. Cage, Berio, Boulez, Milton Babbitt, Luigi Nono and Edgard Varèse all wrote electroacoustic music.

From the early 1950s onwards, Cage introduced elements of chance into his music. Process music (Karlheinz Stockhausen Prozession , Aus den sieben Tagen ; and Steve Reich Piano Phase , Clapping Music ) explores a particular process which is essentially laid bare in the work. The termexperimental music was coined by Cage to describe works that produce unpredictable results, according to the definition “an experimental action is one the outcome of which is not foreseen.” The term is also used to describe music within specific genres that pushes against their boundaries or definitions, or else whose approach is a hybrid of disparate styles, or incorporates unorthodox, new, distinctly unique ingredients.

Important cultural trends often informed music of this period, romantic, modernist, neoclassical, postmodernist or otherwise. Igor Stravinsky and Sergei Prokofiev were particularly drawn to primitivism in their early careers, as explored in works such as The Rite of Spring and Chout . Other Russians, notably Dmitri Shostakovich, reflected the social impact of communism and subsequently had to work within the strictures of socialist realism in their music. Other composers, such as Benjamin Britten ( War Requiem ), explored political themes in their works, albeit entirely at their own volition. Nationalism was also an important means of expression in the early part of the century. The culture of the United States of America, especially, began informing an American vernacular style of classical music, notably in the works of Charles Ives, John Alden Carpenter, and (later) George Gershwin. Folk music (Vaughan Williams’ Five Variants of Dives and Lazarus , Gustav Holst’s A Somerset Rhapsody ) and Jazz (Gershwin, Leonard Bernstein, and Darius Milhaud’s La création du monde ) were also influential.

In the latter quarter of the century, eclecticism and polystylism became important. These, as well as minimalism, New Complexity, and New Simplicity, are more fully explored in their respective articles.

- Authored by : Elliott Jones. Provided by : Santa Ana College. Located at : http://www.sac.edu . License : CC BY: Attribution

- History. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/20th-century_classical_music#History . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Latest News

How Sweet It Is: The Incomparable Soul Of Marvin Gaye

‘live fast, love hard, die young’: faron young becomes a country king, so many places: the life of leon russell, ‘pink friday: roman reloaded’: how nicki minaj shot for the mainstream, godfather of fusion: a salute to larry coryell, ‘commodores’ album: motown stars make it look ‘easy’, the soul of marvin gaye: how he became ‘the truest artist’, heart announces additional ‘royal flush’ 2024 tour dates, dreamer boy announces ‘lonestar,’ shares ‘if you’re not in love’, shania twain shares vevo footnotes for ‘man i feel like a woman’, the smashing pumpkins announce more summer tour dates, nelly furtado recruits juanes for ‘gala y dalí’, casey benjamin, saxophonist with robert glasper experiment, dies aged 46, maggie rogers announces two intimate london shows for fall 2024, say it loud: how music changes society.

A song doesn’t have to have a message in order to change society. Race relations, gender equality and identity politics have all been shaped by music.

Published on

Songs are such powerful things: they can reassure, soothe, inspire and educate us – and that’s just for starters. Perhaps one reason for this is because they are performed by real people, human failings and all, which is why reading lyrics on paper will never quite add up. Songs have always held a mirror to the world, reflecting the things going on around us, and, arguably, music changes society like no other artform.

Traditionally, songs were passed down through the generations by being sung, like oral histories. Come the 20th century, however, technological advances quickly made the world a much smaller place and, thanks to cheap, widely-available audio equipment, songs could suddenly be distributed on a much larger scale.

While you’re reading, listen to our Music For Change playlist here .

Before long, records became agents of musical revolution. Prior to the availability of high-fidelity audio recordings, you’d have had to live near – and be able to afford visits – to the opera to hear world-changing music. Similarly, growing up in the UK, for example, you’d have never heard the blues as it was meant to be sung. The advent of recording technology changed that, significantly broadening people’s musical horizons. Now powerful spirituals were being recorded and distributed widely and quickly, enabling singers to share their experiences with ever increasing audiences, forging emotional connections with listeners in ways that sheet music found impossible. Songs could shape listeners in new ways, challenging people’s preconceived ideas of the world, shining a light on things that weren’t spoken of in the news of the day.

“A declaration of war”

The impact of Billie Holiday ’s 1939 version of Abel Meeropol’s “Strange Fruit” is a perfect example of music’s ability to change society. The record producer and co-founder of Atlantic Records, Ahmet Ertegun, called it, “a declaration of war… the beginning of the civil-rights movement.” Until the late 30s, music hadn’t directly confronted the issues of racism and segregation in the US. Venues were segregated, with famous black musicians such as Louis Armstrong labeled as “Uncle Toms,” suggesting they’d only play for white audiences, where the money really was.

The first venue to publicly integrate musicians was New York’s Café Society. According to the owner at the time, Barney Joseph: “I wanted a club where blacks and whites worked together behind the footlights and sat together out front. There wasn’t, so far as I know, a place like it in New York or in the whole country.” Still, when Holiday first performed “Strange Fruit” at Joseph’s insistence, she was afraid. The song was a stark description of a postcard Meeropol had seen of black bodies hanging from a tree after a lynching. Back then, popular song wasn’t a place for such brutal truths, and Holiday would have been sorely aware of the trouble it could create. She later described what happened the first time she sang it in her autobiography: “There wasn’t even a patter of applause when I finished. Then a lone person began to clap nervously. Then suddenly everybody was clapping.”

The song went on to sell over a million copies when it was finally released by Holiday, and who knows how many hearts and minds it changed? The clue to its power might be in the way the lyric simply describes the scene: it’s presented for the listener to take at face value. Without suggesting solutions or even presuming to inform of the extent of the problem, “Strange Fruit” simply instills feelings of disgust and deep sadness. Those affected by the song went on to march together in support of Martin Luther King, Jr , and their grandchildren did the same for the Black Lives Matter movement. It had an immense impact on the way people thought about race.

Break down barriers

Segregation and institutionalized racism caused a deep rift in US society that continues to this day, but music was always at the forefront when it came to change. Swing-era bandleader Benny Goodman made history when he graced the hallowed stage of New York’s Carnegie Hall on January 16, 1938. Not only was the show notable for being the first occasion that real jazz, in all it’s improvised, hard-swinging glory, had been played at the prestigious venue, thus giving the music real cultural cache, but Goodman’s group was racially integrated. That it was unusual for a jazz group to feature black musicians seems absurd to modern sensibilities, but back then, so-called “European” jazz dominated concert halls. It was clean, symphonic, very white and a distant relation to the exciting jazz pioneered by the likes of Sidney Bechet and Duke Ellington . The audience reaction to the long-sold out concert was ecstatic, breaking down barriers for black performers.

While it would take politicians until 1964 to abolish the Jim Crow laws (state and local laws that enforced social segregation in the southern US states), musicians cared more about the skills and character of an individual than the color of their skin. Back in the 50s, white jazz pianist Dave Brubeck repeatedly ignored pressure from gig promoters across the US to replace the black bassist in his quartet, Eugene Wright. Brubeck not only made it publicly known that he would do no such thing, but insisted that Wright share the same facilities as his bandmates musicians and refused to perform for segregated audiences.

And then there’s the enormously influential Booker T & The MGs . As Stax Records’ house band the group were responsible for backing the likes of Otis Redding , Wilson Pickett, Sam & Dave, and Carla Thomas, among countless others. But many listeners would have been surprised to learn that a group that soulful was split evenly between black and white members.

The MGs were like their label in microcosm: the founders of Stax, a pair of white siblings called Jim Stewart and Estelle Axton, had, in 1957, set the label up in a predominately black neighborhood of Memphis, looking to sign any artist with the right sound, regardless of skin color – a bold move in a still-segregated city. All of the musicians who formed Booker T & The MGs had attended segregated schools, and, at the time of their 1962 hit single, “Green Onions” , wouldn’t have been able to even sit together in a restaurant in Memphis. Yet they showed America that music had the power to bring people together, and challenged prejudices wherever they played. Several years later, Sly And The Family Stone took The MGs’ mixed-race template and upped the ante by becoming one of the first mixed-race and mixed-sex bands, finding huge success with singles such as “Dance To The Music” and their equality anthem “Everyday People.”

Walk with a bit more pride

The advent of television made pop music more potent still. There was something even more thrilling about seeing songs performed in the flesh, and artists recognized the medium’s potential for challenging audience perceptions. Take for example Dusty Springfield ’s regular show on BBC television in the UK. Springfield was only too aware that, as a white artist heavily influenced by black music, she had a debt of sorts to pay, and was insistent that her show featured black musicians. It was a bold move at the time, especially considering that Dusty was a mainstream program broadcasting to areas of the UK that would have been predominately white. Seeing those artists revered on national television would, however, have had quite an impact on audiences.

Over in the States, Motown, another color-blind soul label, launched its own assault on TV. Oprah Winfrey has spoken of the impact of seeing The Supremes on The Ed Sullivan Show – missing much of the performance while she phoned friends to tell them “black people are on television.” For African-American children in 1969, seeing the younger Jackson 5 beamed into your home was like watching your schoolmates set foot in places you could only ever dream of. Suddenly, success doesn’t seem completely unattainable. Michael Jackson looks sheepish, even, as he introduces “I Want You Back” on Ed Sullivan , but once it starts he’s totally convincing as a pop star – just about the most important thing a person could be in the late 60s.

Collapsing in mock anguish, as if his ten-year-old heart has somehow inherited the strain of a middle-aged divorcee and is buckling at the emotional weight of it, the young Jackson just about burns a hole in the floor of the television studio with his dance moves. And his flamboyant costume includes a purple hat and long, pointed collars – but what of it? The song he’s singing isn’t remotely political in subject matter – he sings sweetly of heartbreak, makes it sound appealing, even – but it changes everything: the way you see yourself, your family, your friends. That kid is a star. Seeing him sets off a near-synapse frying chain reaction of thoughts: anything is possible; the streets look somehow different when you go outside; you start to walk with a bit more pride.

Make your voice heard

Pop music has the ability to encourage individuals to think about where they’re going in the world; to inform the decisions they make; to help forge an identity. But while music might be consumed in solitude, taking a hold on imaginations as you listen in bedrooms and on headphones, it has a unifying effect. An individual touched by music is not isolated. They are one of millions of people affected by those moments, and in turn that has a huge effect on society.

The label that really did the most to show how music could change things was Motown. Launched in 1959 with an $8,000 loan, Motown’s founder, Berry Gordy, was the first African-American to run a record label. That would have been enough to earn him a place in the history books, but the music and stars that emerged from under his watchful eye came to dominate American music over the next few decades – indeed, fashion “The Sound Of Young America” – taking it worldwide and giving black artists opportunities that, just years before, would have been considered deeply fanciful.

Gordy’s artists produced irresistible, soulful pop that appealed across the board and which continues to resonate to this day. Stevie Wonder , The Supremes , Marvin Gaye , Smokey Robinson , Jackson 5, Gladys Knight & The Pips, The Temptations … their songs won hearts across the world and did inestimable good in opening closed minds to the idea that African-American musicians were just as worthy of attention as their white counterparts. The two minutes and 36 seconds of The Supremes’ perfect pop confection, “Baby Love,” might well have done more good than years of civil-rights campaigning – yes, music is that powerful.

As its artists matured, Motown released music that went beyond pop: Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On , Stevie Wonder’s Innervisions , The Temptations’ “Papa Was A Rolling Stone” – all were considered statements of social awareness and black pride that mirrored the work of contemporaries such as Curtis Mayfield, James Brown , Sly Stone and Isaac Hayes . The groundbreaking work of this generation of black artists was continued by the likes of Gil Scott-Heron, Funkadelic and Parliament, which led to hip-hop. And the repercussions are still being felt today – R&B and hip-hop have been energized by the Black Lives Matter movement and vice versa.

Artists such as Kendrick Lamar and Solange, D’Angelo , Beyoncé, Blood Orange and Common , among many more, have released albums in recent years that have tackled America’s struggle with race relations head on. And in keeping with the complicated, multi-faceted nature of the problem, the songs come in many different forms, ranging from the tormented self-examination of Kendrick Lamar’s “The Blacker The Berry” (from 2015’s To Pimp A Butterfly , which also included the movement’s bona fide anthem in the defiant “Alright”) to Solange’s eloquent request that her culture is respected: “Don’t Touch My Hair” (from 2016’s A Seat At The Table ).

Stars have also harnessed the power of video to tell their story, Beyoncé’s Lemonade was effectively an album-long expression of the black woman’s experience in America, and the accompanying “visual album” didn’t pull any punches. In the clip for “Forward,” the mothers of Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner and Michael Brown – the young black men whose deaths launched the Black Lives Matter movement – are seen holding photographs of their sons, while the video for “Formation” is a commentary on police brutality, self-love, the devastation caused by Hurricane Katrina and black wealth.

Just as reliant on provocative imagery and symbolism is the brilliant clip for Childish Gambino’s 2018 single, “This Is America,” which focuses on themes of gun violence and how black culture is often co-opted by white audiences for mass entertainment. The key here is that these have all been massive hits; the artists in question are producing radical work that communicates with mass audiences, showing that music has lost none of its power to foster change.

You don’t own me

Music has also made huge leaps and bounds for gender equality. Things are by no means perfect – women in bands are still sometimes treated as a novelty whose musical ability is met with surprise. But there’s a long history of songs that stand up for women’s rights.

Back in 1963, the message of Lesley Gore’s “You Don’t Own Me” felt shocking to many. Though the song was written by two men, Gore delivered it with such sass that she owned it. She later said, “When I first heard that song at the age of 16 or 17, feminism wasn’t quite a going proposition yet. Some people talked about it, but it wasn’t in any kind of state at the time. My take on that song was: ‘I’m 17, what a wonderful thing, to be able to stand up on a stage and shake your finger at people and sing “You don’t own me”.’”

Gore’s spirit lived on through every woman who has ever decided they wouldn’t be told what to do by men, from Aretha repurposing (and ultimately owning) Otis Redding’s “Respect,” to the formidable likes of The Slits, Bikini Kill, Sleater-Kinney, and Le Tigre, to the inspiring pop of Spice Girls and Destiny’s Child.

Just like the child watching Michael Jackson in 1969, imagine girls all over the world watching slack-jawed as Spice Girls ran amok in some dusty mansion for the “Wannabe” video in 1996 – somersaulting across the desserts, making snooty old men blush; singing a song about female friendship and empowerment that they’d written. The likes of “Wannabe” had the effect of making women all over the world more determined that they won’t be ignored. It’s a spirit that’s exemplified by the likes of Lorde, Taylor Swift , Grimes, and St Vincent – powerful women seizing total creative control and bending the industry (and society) to their vision.

Paradigms of their age

While music played a vital role in changing attitudes towards race and sexism in the US, it challenged the status quo elsewhere in plenty of different ways. The impact of The Beatles is a perfect example of the transformative power of pop music. It requires a deep breath before listing the ways in which their music helped change society: earning their own songwriting credits; bringing regional accents into popular culture; their utter delight in irreverence; their haircuts; their hold over screaming fans; their popularisation of esoteric ideas and foreign cultures…

Allen Ginsberg once remarked that they represented “the paradigm of the age”, and it’s easy to see why. The 60s swung to The Beatles’ beat. Their influence was everywhere. When John Lennon sang “Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds” and fans took it as a reference to LSD, generations of recreational drug use was affected. When his famous interview claiming that The Beatles were “more popular than Jesus” (part of a wider argument about the fading influence of religion) was brought to the attention of the American public, it unleashed incredible amounts of vitriol – but no doubt lit plenty of lightbulbs in the heads of his fans.

The Beatles – and the 60s as a whole – encouraged people to think outside the norm and to challenge accepted wisdom, something that has since been integral to the ways in which music changes society. A striking example came with the punk movement. It didn’t take long for the UK press to reduce a creative youth movement to tabloid caricature, but the central premise of the DIY punk movement – that you didn’t need a record company, or even any musical talent to make yourself and your opinions heard – has had a massive impact on society. The debut EP from Buzzcocks, Spiral Scratch , wasn’t even particularly political in nature, but the fact that they released it themselves, demystifying the process of releasing music, meant it was one of the most influential records of its time, inadvertently inspiring generations of artists.

Becoming more fluid

Indeed, one of the things pop music does, whether by design or not, is reflect the ideas and lifestyles of creative and interesting, forward-thinking people, thrusting them into the mainstream, be it by way of a catchy chorus, infectious beat or an audacious gimmick. It’s just about the fasting-acting agent of change on society imaginable; a song has the ability to turn the status quo on its head.

Equally, a song can speak to an oppressed group of people. Much like “Glad To Be Gay,” a 1978 song by Tom Robinson Band which dealt with public attitudes towards homosexuality by meeting them head-on in a show of defiance. Considering that so few pop songs had dealt explicitly with the subject up to that point (though plenty had offered veiled celebrations, from Cole Porter’s “You’re The Top” to Little Richard ’s “Tutti Frutti,” while David Bowie ’s Top Of The Pops performance of “Starman” included a gesture that empowered almost every gay young man who witnessed it), and that homosexuality in the UK had only been decriminalized in 1967, it’s an extraordinarily brave song that would have helped so many. Since then, things have improved and gay culture has become a much more accepted part of the mainstream, with music a huge conduit enabling that to happen.

As attitudes towards sexuality are becoming more fluid, musicians are once again at the forefront, just as they were in the 80s, when sexual provocateurs such as Prince and Madonna brought a more liberal approach to sexuality into the mainstream. On the eve of releasing his debut album proper, the R&B sensation Frank Ocean, currently one of the most influential musicians on the planet, posted a short note on his Tumblr which alluded to having had relationships with men and women. The album itself, Channel Orange , and its follow-up, Blonde , explored similar lyrical territory. His ex-Odd Future bandmate, Tyler, The Creator, followed suit before the release of his 2017 album, Flower Boy , and was met with overwhelming support. Both of these artists release music in genres that have been traditionally hostile towards homosexuality, yet they’ve been strong-minded enough to change that.

As with the race and gender revolutions of the past, music is once again at the forefront of contemporary discourse. Outspoken artists such as Anohni and Christine & The Queens, up to mainstream provocateurs such as Lady Gaga , are spreading awareness of gender fluidity, reaching audiences, and breaking down preconceived ideas. Just like music always has – and always will.

Discover more about how LGBTQ musicians broke barriers to the mainstream.

February 7, 2019 at 8:33 pm

Where is Elvis!!!!

John Bianchi

July 11, 2019 at 9:56 pm

Confucius said that if you want to know the quality of a society, listen to its music. Well look at the crap that passes as “music” here. It’s just political complaining in the guise of entertainment. Nothing to do with music. Most of the tracks aren’t even played by musicians- just digital tracks designed to fill. True music is a reflection of the spirit of mankind, and has nothing to do with politics or personal grievances. Observe what it has done to fracture our society.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Skip to search box

- Skip to main content

Princeton University Library

20th- & 21st-century music: a guide to research and resources.

- Introduction

- Search Strategies

- Genres & Repertoire

- Books & Catalogs

Key Journals

Music periodical databases.

- Composers & Publishers

- Performance Practice & Performers

- Contemporary Music Review

- Perspectives of New Music

- Twentieth-Century Music

- 21st Century Music

Use these resources primarily to find print and online articles, reports, notices, reviews, and other writings on the music industry published in music journals, trade publications, and magazines.

- RILM Abstracts of Music Literature with Full Text This link opens in a new window Covers all aspects of music, including historical musicology, ethnomusicology, instruments and voice, dance, and music therapy. If related to music, works in other fields, such as literature, dramatic arts, visual arts, anthropology, sociology, philosophy and physics are included. 1967+

- Music Periodicals Database This link opens in a new window Indexes music journals covering a broad scope of research from performance, theory and composition to music education, jazz and ethnomusicology. Provides selected full text coverage of the most important music journals, and both scholarly and popular publications.

- Music Index with Full Text This link opens in a new window Includes international music periodicals covering classical, popular and world of music. Comprehensively cites articles and news about music, musicians and the music industry as well as book and concert reviews and obituaries. 1970+ more... less... Print volumes covering 1949-1972 are available in Mendel Music Library: Reference (SV) ML 118 M84.

- << Previous: Books & Catalogs

- Next: Composers & Publishers >>

- Last Updated: Jul 13, 2023 4:06 PM

- URL: https://libguides.princeton.edu/20th-21st-century-music

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

Music in the renaissance.

ex "Kurtz" Violin

Andrea Amati

Double Virginal

Hans Ruckers the Elder

Cornetto in A

possibly Georg Voll

Sixtus Rauchwolff

Claviorganum

Lorenz Hauslaib

Tenor Recorder

Rectangular Octave Virginal

Rebecca Arkenberg Department of Education, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 2002

Music was an essential part of civic, religious, and courtly life in the Renaissance. The rich interchange of ideas in Europe, as well as political, economic, and religious events in the period 1400–1600 led to major changes in styles of composing, methods of disseminating music, new musical genres, and the development of musical instruments. The most important music of the early Renaissance was composed for use by the church—polyphonic (made up of several simultaneous melodies) masses and motets in Latin for important churches and court chapels. By the end of the sixteenth century, however, patronage had broadened to include the Catholic Church, Protestant churches and courts, wealthy amateurs, and music printing—all were sources of income for composers.

The early fifteenth century was dominated initially by English and then Northern European composers. The Burgundian court was especially influential, and it attracted composers and musicians from all over Europe. The most important of these was Guillaume Du Fay (1397–1474), whose varied musical offerings included motets and masses for church and chapel services, many of whose large musical structures were based on existing Gregorian chant. His many small settings of French poetry display a sweet melodic lyricism unknown until his era. With his command of large-scale musical form, as well as his attention to secular text-setting, Du Fay set the stage for the next generations of Renaissance composers.

By about 1500, European art music was dominated by Franco-Flemish composers, the most prominent of whom was Josquin des Prez (ca. 1450–1521). Like many leading composers of his era, Josquin traveled widely throughout Europe, working for patrons in Aix-en-Provence, Paris, Milan, Rome, Ferrara, and Condé-sur-L’Escaut. The exchange of musical ideas among the Low Countries, France, and Italy led to what could be considered an international European style. On the one hand, polyphony or multivoiced music, with its horizontal contrapuntal style, continued to develop in complexity. At the same time, harmony based on a vertical arrangement of intervals, including thirds and sixths, was explored for its full textures and suitability for accompanying a vocal line. Josquin’s music epitomized these trends, with Northern-style intricate polyphony using canons, preexisting melodies, and other compositional structures smoothly amalgamated with the Italian bent for artfully setting words with melodies that highlight the poetry rather than masking it with complexity. Josquin, like Du Fay, composed primarily Latin masses and motets, but in a seemingly endless variety of styles. His secular output included settings of courtly French poetry, like Du Fay, but also arrangements of French popular songs, instrumental music, and Italian frottole.

With the beginning of the sixteenth century, European music saw a number of momentous changes. In 1501, a Venetian printer named Ottaviano Petrucci published the first significant collection of polyphonic music, the Harmonice Musices Odhecaton A . Petrucci’s success led eventually to music printing in France, Germany, England, and elsewhere. Prior to 1501, all music had to be copied by hand or learned by ear; music books were owned exclusively by religious establishments or extremely wealthy courts and households. After Petrucci, while these books were not inexpensive, it became possible for far greater numbers of people to own them and to learn to read music.

At about the same period, musical instrument technology led to the development of the viola da gamba , a fretted, bowed string instrument. Amateur European musicians of means eagerly took up the viol, as well as the lute , the recorder , the harpsichord (in various guises, including the spinet and virginal), the organ , and other instruments. The viola da gamba and recorder were played together in consorts or ensembles and often were produced in families or sets, with different sizes playing the different lines. Publications by Petrucci and others supplied these players for the first time with notated music (as opposed to the improvised music performed by professional instrumentalists). The sixteenth century saw the development of instrumental music such as the canzona, ricercare, fantasia, variations, and contrapuntal dance-inspired compositions, for both soloists and ensembles, as a truly distinct and independent genre with its own idioms separate from vocal forms and practical dance accompaniment.

The musical instruments depicted in the studiolo of Duke Federigo da Montefeltro of Urbino (ca. 1479–82; 39.153 ) represent both his personal interest in music and the role of music in the intellectual life of an educated Renaissance man. The musical instruments are placed alongside various scientific instruments, books, and weapons, and they include a portative organ, lutes, fiddle, and cornetti; a hunting horn; a pipe and tabor; a harp and jingle ring; a rebec; and a cittern .

From about 1520 through the end of the sixteenth century, composers throughout Europe employed the polyphonic language of Josquin’s generation in exploring musical expression through the French chanson, the Italian madrigal, the German tenorlieder, the Spanish villancico, and the English song, as well as in sacred music. The Reformation and Counter-Reformation directly affected the sacred polyphony of these countries. The Protestant revolutions (mainly in Northern Europe) varied in their attitudes toward sacred music, bringing such musical changes as the introduction of relatively simple German-language hymns (or chorales) sung by the congregation in Lutheran services. Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (1525/26–1594), maestro di cappella at the Cappella Giulia at Saint Peter’s in Rome, is seen by many as the iconic High Renaissance composer of Counter-Reformation sacred music, which features clear lines, a variety of textures, and a musically expressive reverence for its sacred texts. The English (and Catholic) composer William Byrd (1540–1623) straddled both worlds, composing Latin-texted works for the Catholic Church, as well as English-texted service music for use at Elizabeth I ‘s Chapel Royal.

Sixteenth-century humanists studied ancient Greek treatises on music , which discussed the close relationship between music and poetry and how music could stir the listener’s emotions. Inspired by the classical world, Renaissance composers fit words and music together in an increasingly dramatic fashion, as seen in the development of the Italian madrigal and later the operatic works of Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643). The Renaissance adaptation of a musician singing and accompanying himself on a stringed instrument, a variation on the theme of Orpheus, appears in Renaissance artworks like Caravaggio’s Musicians ( 52.81 ) and Titian ‘s Venus and the Lute Player ( 36.29 ).

Arkenberg, Rebecca. “Music in the Renaissance.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/renm/hd_renm.htm (October 2002)

Additional Essays by Rebecca Arkenberg

- Arkenberg, Rebecca. “ Renaissance Violins .” (October 2002)

- Arkenberg, Rebecca. “ Renaissance Keyboards .” (October 2002)

- Arkenberg, Rebecca. “ Renaissance Organs .” (October 2002)

Related Essays

- Painting in Italian Choir Books, 1300–1500

- Renaissance Keyboards

- Renaissance Organs

- Art and Love in the Italian Renaissance

- Burgundian Netherlands: Court Life and Patronage

- Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi) (1571–1610) and His Followers

- Courtship and Betrothal in the Italian Renaissance

- The Development of the Recorder

- Elizabethan England

- Flemish Harpsichords and Virginals

- Food and Drink in European Painting, 1400–1800

- Gardens in the French Renaissance

- Joachim Tielke (1641–1719)

- Music in Ancient Greece

- Northern Italian Renaissance Painting

- The Printed Image in the West: History and Techniques

- The Reformation

- Renaissance Violins

- Sixteenth-Century Painting in Venice and the Veneto

- The Spanish Guitar

- Titian (ca. 1485/90?–1576)

- Violin Makers: Nicolò Amati (1596–1684) and Antonio Stradivari (1644–1737)

- Woodcut Book Illustration in Renaissance Italy: Venice in the Sixteenth Century

List of Rulers

- List of Rulers of Europe

- Central Europe (including Germany), 1400–1600 A.D.

- Florence and Central Italy, 1400–1600 A.D.

- France, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Great Britain and Ireland, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Iberian Peninsula, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Low Countries, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Rome and Southern Italy, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Venice and Northern Italy, 1400–1600 A.D.

- 15th Century A.D.

- European Decorative Arts

- High Renaissance

- Musical Instrument

- Northern Renaissance

- Percussion Instrument

- Plucked String Instrument

- Renaissance Art

- String Instrument

- Wind Instrument

Artist or Maker

- Amati, Andrea

- Amati, Nicolò

- Beham, Hans Sebald

- Cuntz, Steffan

- Hauslaib, Lorenz

- Rauchwolff, Sixtus

- Ruckers, Hans, the Elder

- Vell, Georg

Online Features

- The Artist Project: “Cory Arcangel on the harpischord”

- MetMedia: “Double” from the Sarabande of Partita no. 1 in B minor by Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) and Gigue from Partita No. 2 in D minor by Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

However, the 20th century saw the rise of great composers such as Arnold Schoenberg, Charles Ives and Igor Stravinsky whose contributions to the world of music brought dynamic changes. In the twentieth century music was no longer constrained to opera-houses, clubs, and concerts and this freedom brought experimentation with new styles of music ...

All the Western classical music periods up until the turn of the 20th century had dominating styles and conventions. Composers tended to stick to these and lots of the music composed during that time had a similar 'sound'.But, the 20th century saw composers start to escape from these broad traditions of the era and classical music branched off into lots of different sub-movements.

The 20th century was clearly a period of widespread experimentation and many composers wanted the freedom to explore new compositional approaches without the restrictions and expectations that accompany traditional genres. Even when longstanding genres were used, composers felt very comfortable abandoning the traditional structures of those genres.

780 Words4 Pages. Music from the first decade of the 20th century wasn't a big shift from the previous decade which included both ragtime and romantic music. First, ragtime music would begin in the mid-1890s and continue throughout the next two decades. This would mean that Americans enjoyed and listened to the same type of music for two decades.

Music and its Influence on 20th Century American History With the start of the 20th century music began to play a huge part in the rapidly maturing United States. Music of the 20th century was not only there to entertain the people but it was more. It was now used to influence and manipulate the listeners. Artists had a goal to entertain and to ...

The lives of musicians, composers, and makers of musical instruments were greatly altered by these social changes. In earlier times, musicians were usually employed by either the church or the court and were merely servants to aristocratic circles. ... The Cambridge History of Nineteenth-Century Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press ...

Our phrase, "the evolution of 2oth-century music," tends to make us think of individual works or individual composers as specimens of a. race, or as various races of one species. We search for an image of the norm of the species, and for an indication of the direction of future evolution. These are chimeras.

American popular music, but rather to use these "artifacts" to chart and make sense of political, social, cultural, and economic change in twentieth century America. Demonstrate the "historical way of thinking" The recitations and written assignments in this course will provide you with an opportunity to

20th-century classical music. Contemporary classical music, covering the period c. 1970-2000.

Western music, Music produced in Europe as well as the music derived from European forms from ancient times to the 21st century. All ancient civilizations entered historical times with a flourishing musical culture. The primary function was apparently religious. Other musical occasions were equally functional: stirring incitements to military ...

Rock remains the most democratic of mass media—the only one in which voices from the margins of society can still be heard out loud. Yet, at the beginning of the 21st century, rock and the music industry faced a new crisis. The development of digital technology meant that music could now be stored on easy-to-use digital files, which could in ...

Come the 20th century, however, technological advances quickly made the world a much smaller place and, ... The label that really did the most to show how music could change things was Motown ...

This guide presents basic and specialized resources for researching the music composed during the 20th- and 21st-Century. It broadly covers all the styles, genres, cultures, creators, and social aspects of music that flourished during this time period. Co

Satisfactory Essays. 700 Words. 3 Pages. Open Document. During the 20th century, social changes combined with new technologies created a mass market for popular music and contributed to how music was created, shared, and appreciated. The advancement of technology had a huge impact on the evolution of music.

Twentieth century music, the pieces that were written during 1901-2000, is the most experimenting music throughout the past era. Lots of new style music was developed in this twentieth century period, such as Surrealism, neo-classicism, minimalism…etc. This music was having a huge influence toward not only to music, but also to the whole world.

Abstract. The aim of this article is to establish the extent to which the history of music can offer new perspectives on the modern period. We need a change of perspective, moving away from the aesthetic debates on music to an investigation of actual experiences and practices of participants.

1) Romantic music in the late 19th/early 20th century brought innovations like increased chromaticism and breaking of traditional rules and structures. Composers like Wagner and Schoenberg pushed chromaticism further. 2) New genres developed like musical nationalism, representing individual countries, and Impressionism which sought to musically depict moods and emotions rather than tell ...

During the 20th century there was a vast increase in the variety of music that people had access to. Prior to the invention of mass market gramophone records (developed in 1892) and radio broadcasting (first commercially done ca. 1919-20), people mainly listened to music at live Classical music concerts or musical theatre shows, which were ...

The early 20th Century saw the beginnings of a music publishing industry for traditional Irish musicians. The first great published collections of traditional music intended for traditional musicians were produced in the 1900s and 1910s in Chicago by Capt. Francis O'Neill, originally from Cork and head of the Chicago Police.

In the first half of the century, newspapers, song sheets, and songsters print song lyrics, but music notation is usually neglected in favor of the mnemonic cue "sung to the tune of . . . ." Printed music (vocal as well as instrumental) is slower to expand. Music is integral to American life in the 19th century.

Music was an essential part of civic, religious, and courtly life in the Renaissance. The rich interchange of ideas in Europe, as well as political, economic, and religious events in the period 1400-1600 led to major changes in styles of composing, methods of disseminating music, new musical genres, and the development of musical instruments.

The Renaissance period of classical music spans approximately 1400 to 1600. It was preceded by the Medieval period and followed by the Baroque period. The Renaissance era of music history came significantly later than the era of Renaissance art, which arguably peaked during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, yet the Renaissance music era ...