Free Comparative Literature Essay Examples & Topics

Comparative literature explores the relationship between works of fiction of different cultures and times. Its purpose is to establish the connection between specific genres, styles, and literary devices and the historical period. At the same time, it provides an insight into the meaning hidden between the lines of a given text.

What is a literary comparison essay? This academic paper requires a specific methodology but follows the typical rules. A student is expected to perform comparative textual analysis of a short story, novel, or any other piece of narrative writing. However, it is vital to remember that only the pieces with something in common are comparable.

This is where all the challenges start. Without an in-depth literature review, it is not always clear which works can and should be compared. Which aspects should be considered, and which could be left out? The structure of a comparative essay is another stumbling rock.

For this reason, our team has prepared a brief guide. Here, you will learn how to write a successful comparative literature essay and, more importantly, what to write in it. And that is not all! Underneath the article, we have prepared some comparative literary analysis essay examples written by students like you.

How to Write a Comparative Essay

Comparative literary analysis requires you to know how to correlate two different things in general. So let us start from the basics. This section explains how to write a comparative paper.

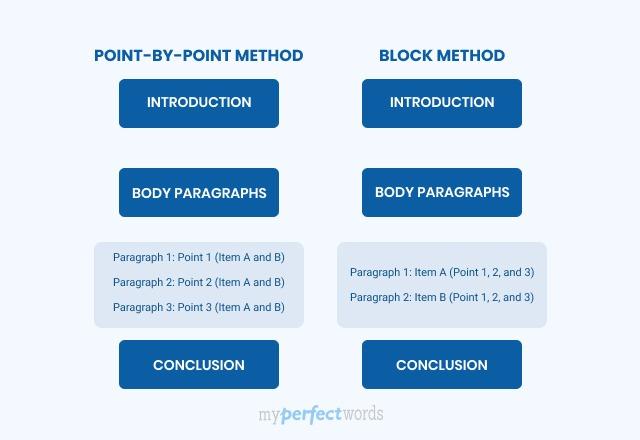

A good comparison essay structure relies on two techniques:

- Alternating or point-by-point method.

Using this technique, you dedicate two paragraphs for each new comparison aspect, one for each subject. It is the best way to establish similar and different features in the two novels. Such comparative analysis works best for research, providing a detailed and well-structured text.

1st Body Paragraph: Social problems in Steinback’s works.

2nd Body Paragraph: Social problems in Hemingway’s works.

3rd Body Paragraph: Psychological problems in Steinback’s works.

4th Body Paragraph: Psychological problems in Hemingway’s works.

5th Body Paragraph: Interpersonal problems in Steinback’s works.

- Block or subject-by-subject method .

This approach means that you divide your essay in two. The first part discusses one text or author, and the second part analyzes the other. The challenge here is to avoid writing two disconnected papers under one title.

For this purpose, constantly refer the second part to the first one to show the differences and similarities. You should use the technique if you have more than two comparison subjects (add another paragraph for each next one). It also works well when there is little in common between the subjects.

1-3 Body Paragraphs: Description of rural labor in Steinback’s works.

4-6 Body Paragraphs: Description of rural labor in Hemingway’s works.

You will formulate a thesis and distribute the arguments and supporting evidence depending on the chosen structure. You can consult the possible options in our comparative literature essay examples.

How to Conduct Literary Comparison: Essay Tips

Let us move to the main point of this article: the comparison of literature. In this section, we will discuss how to write an ideal essay in this format.

We suggest you stick to the following action plan:

- Choose literary works to compare. They should have some features in common. For example, the protagonist faces the same type of conflict, or the setting is the same. You should know the works well enough to find the necessary passages. Check the comparative literature examples below if you struggle with the step.

- Select the topic, thinking of similarities. The broader the matter, the more challenging the writing. A comparative study of the protagonists in two books is harder than analyzing the same theme that appears in them. Characters may have little in common, making the analysis more complicated.

- Find both differences and similarities. Once you’ve formulated the topic , make a list of features to compare. If the subjects are too different, choose the block method of contrasting them. Otherwise, the alternating technique will do.

- Formulate a thesis statement that has a comparative nature. It should convey the gist of the essay’s argument. Highlight the relationship between the books. Do they contradict, supplement, develop, or correct each other? You can start the thesis statement with “whereas.” For example, “Whereas Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights and Darcy in Pride and Prejudice are full of pride, this trait leads them to different troubles.”

- Outline and list key elements. Select three to six comparable aspects depending on your essay’s expected length. Then, plan in what order you’ll present them and according to which technique.

- Link elements and write. Distribute the features among the comparative paragraphs. If you wish to prove that the books are more different than alike, start with the most diverging factors and move to the most similar ones.

That’s it! Thank you for reading this article. For more examples of comparative literature essays, check the links below.

744 Best Essay Examples on Comparative Literature

Hamlet, laertes, fortinbras: revenge for the deaths of their fathers, “the lady with the pet dog”: oates & chekhov [analysis], imagery and theme in william blake’s poems, blindness in oedipus rex & hamlet.

- Words: 2788

Gilgamesh and Odysseus: A Comparison

- Words: 1373

The Aspects of Human Nature That George Orwell Criticizes in His Work 1984 Compared to Today’s World

- Words: 1098

Compare and Contrast “To His Coy Mistress” & “To the Virgins”

- Words: 2413

Defoe’s “Robinson Crusoe” and Swift’s “Gulliver” Comparative Analysis

Feminist perspective: “my last duchess”, “to his coy mistress”, and “the secretary chant”.

- Words: 1321

Dante and Chaucer: The Divine Comedy and The Canterbury Tales Comparison

Compare and contrast wordsworth and keats.

- Words: 2298

Comparison of Douglass and Jacobs Narratives

- Words: 1486

The Absurd Hero as an Interesting Type of Hero in Literature and Movies

- Words: 1248

William Shakespeare “Romeo and Juliet” and “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”

- Words: 1773

“Annabel Lee” and “The Raven” by Edgar Allan Poe

Atwood’s “dancing girls” and achebe’s “the madman”.

- Words: 2787

Comparison of Ideas Thomas More’s ‘Utopia’ and Machiavelli’s ‘The Prince’

- Words: 1502

Macbeth & Frankenstein: Compare & Contrast

- Words: 2483

The Great Gatsby and Winter Dreams by Scott Fitzgerald

- Words: 1695

William Blake’ Poems Comparison: “The Lamb” and “The Tyger”

Joy harjo’s “she had some horses” analytical essay.

- Words: 1215

Peter Singer and Onara O’Neill: Comparative Position

- Words: 1114

The Play “Trifles” and the Short Story “A Jury of Her Peers” by Glaspell

A rose for emily: faulkner’s short story vs. chubbuck’s film.

- Words: 1103

The Concept of True Love

- Words: 1369

Racism in the “Dutchman” by Amiri Baraka

- Words: 1401

Power and Corruption in Shakespeare’s Plays

- Words: 2918

“Appointment With Love” and “The Gift of the Magi” Comparison

- Words: 1529

Characterization’s Importance in Literature

- Words: 1135

Harriet Jacobs and Frederick Douglass Literature Comparison

- Words: 2254

Nascent Colonialism in Robinson Crusoe and Gulliver

- Words: 2993

Women in “The Lady with the Dog” by Chekhov and “The Dead” by Joyce

- Words: 1153

Comparison of “Hamlet”, “King Lear” and “Othello” by Shakespeare

- Words: 1687

Comparison of Shakespeare’s and Donne’s Works

- Words: 1113

“A Doll’s House” and “Death of a Salesman” Comparison

- Words: 1414

Lamb to the Slaughter: Movie vs. Book

- Words: 1384

Confessional Poetry

- Words: 1137

The Mother Image in a Poem, a Song, and an Article

- Words: 1494

Sex and Sexuality in “Dracula” and “The Bloody Chamber”

- Words: 2053

“The Hobbit”: Book vs. Movie

- Words: 2495

Comparison of the Opening Scene of Macbeth by Orson Welles and The Tragedy of Macbeth by Roman Polanski

Tim burton interpretation of “alice in wonderland”.

- Words: 3660

Robert Frost and Walt Whitman: Poems Comparison

“the fall of the house of usher” & “the cask of amontillado”: summaries, settings, and main themes.

- Words: 1258

Ken Liu’s “Good Hunting” and The Perfect Match

British literature: beowulf vs. macbeth.

- Words: 1155

Rama and Odysseus as Eastern and Western Heroes

- Words: 1191

Animals as Symbols of the Human Behaviour

- Words: 2856

“Hills Like White Elephants”: Argument Comparison

Role of fate and divine intervention in oedipus and the odyssey.

- Words: 1163

Comparative Literature for Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning

- Words: 2289

Comparing Robert Frost’s Poems: The Road Not Taken and A Question

Roman & greek mythology in pop culture: examples, referenses, & allusions, “the bacchae” by euripides, and “the secret history” by donna tartt.

- Words: 1920

Salih’s “Season of Migration to the North” and “Othello” by Shakespeare

- Words: 2783

Father-Son Relationships in “My Oedipus Complex” and “Powder”

- Words: 1875

Nothing Gold Can Stay vs. Because I Could Not Stop for Death

- Words: 2314

Little Things are Big by Jesus Colon and Thank You M’am by Langston Hughes Analysis + Summary

Comparing and contrasting “the tyger” by william blake with “traveling through the dark” by william stafford, the road as the cave: concept in literature.

- Words: 2450

John Donne’s and Edmund Spenser’s Works Comparison

- Words: 1250

Similarities and differences of The Book of Dede korkut and Layla and majnun

- Words: 1499

Anne Bradstreet and Mary Rowlandson Comparison of Famous Puritan Writers – Compare and Contrast Essay

- Words: 1890

Literature Comparison: A Raisin in the Sun and A Dream Deferred

The death of ivan ilych and the metamorphosis.

- Words: 3084

William Faulkner and Flannery O’Connor: Comparison

- Words: 2094

“Unguarded Gates” by Thomas Aldrich and “Courting a Monk” by Katherine Min Comparing

Concept of science fiction genre in books “dark they were, and golden-eyed” by ray bradbury, and “nightfall” by isaac asimov.

- Words: 1086

‘Sex without love’ by Sharron Olds and ‘She being Brand’ by E.E Cummings

Love for nature: a symptom of a lovesick heart.

- Words: 1010

Comparison Between the Book “Oedipus – The King” and the Movie “Omen”

“raisin in the sun” and “harlem”, a critical comparison of two readings.

- Words: 1182

A High-Toned Old Christian Women by Wallace Stevens

Symbols in marlowe’s “faustus” and milton’s “paradise lost”, oedipus: three-way compare and contrast, “and the soul shall dance” by wakako yamauchi and “silent dancing” by judith ortiz cofer: significance of dancing as theme, “dancing girls” and “madman” by margaret atwood and chinua achebe.

- Words: 2433

Hawthorne’s Concept of Evil in “Rappaccini’s Daughter” and “The Scarlet Letter”

- Words: 2692

Hamlet and King Oedipus Literature Comparison

Symbolism in “the birthmark” & “the minister’s black veil”, appearance vs. reality in shakespeare’s “hamlet” and sophocles’ “oedipus rex”.

- Words: 1831

“The Holy Man of Mount Koya” and “The Narrow Road to Oku”: Comparison of Emotions in Journey Narratives

Contact and comparison of types of conflicts in white’s charlotte’s web and munsch’s the paper bag princess.

- Words: 1125

Comic Heroines in “As You Like It” and Twelfth Night

- Words: 1673

Apartheid Imagery in “A Walk in the Night” and “A Dry White Season”

- Words: 1101

Compare and Contrast Lena Younger and Walter Lee Younger

Homage to my hips, comparison of g. orwell’s “1984”, r. bradbury’s “fahrenheit 451” and a. huxley’s “brave new world”.

- Words: 1716

“The Yellow Wallpaper” by Gilman and “My Last Duchess” by Browning

- Words: 1387

Setting in Steinbeck’s “The Chrysanthemums” and Updike’s “A&P”

Exile of gilgamesh and shakespeare’s prospero, family conflict in unigwe’s, kwa’s, gebbie’s stories, actions’ effects in “doctor faustus” by christopher marlowe, gregor’s relationship with his father in “the matamorphosis”.

- Words: 1983

Chekhov’s vs. Oats’ “The Lady with the Pet Dog”

Symbolism in “everyday use” by walker and “worn path” by welty, novels by conrad and forster comparison.

- Words: 1479

Achilles, Odysseus and Aeneas Comparison

- Words: 1623

“True Grit”: Book and Films Comparison

Hawthorne’s “rappacini’s daughter” and “the birthmark”: comparison, isaac asimov’s “robot dreams” and alex proyas’ “i, robot”.

- Words: 1359

John Milton’s “Paradise Lost” and Christopher Marlow’s “Dr. Faustus”: Comparative Analysis

- Words: 2567

Cameron’s “Hedwig and the Angry Inch” and Plato’s “Symposium”: Comparison

- Words: 1142

Macbeth and Hamlet Characters Comparison

- Words: 1791

Identity in Maupassant’s “The Necklace” and Alvi’s “An Unknown Girl”

“dumpster diving” and “the glass castle”: a brief comparison, coming-of-age fiction: “the bell jar” by sylvia plath.

- Words: 1418

Hindu Creation Myth

A modern cinderella and other stories.

- Words: 2970

Miller’s Death of a Salesman vs. Wilson’s Fences

Relationship between parents and children, “the epic of gilgamesh” and “the bhagavad gita” comparison, naturalism and realism of mark twain and jack london, satan’s comparison in dante and milton’s poems.

- Words: 2684

Homer’s The Iliad and John Milton’s Lost Paradise

- Words: 1907

Racism in Shakespeare’s “Othello” and Dick’s “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?”

- Words: 1873

Existentialism in “Nausea” and “The Stranger”

- Words: 1392

The Drover’s Wife by Murray Bail and Henry Lawson Comparison

The jungle and fast food nation.

- Words: 1493

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Comparing and contrasting in an essay | Tips & examples

Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay | Tips & Examples

Published on August 6, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

Comparing and contrasting is an important skill in academic writing . It involves taking two or more subjects and analyzing the differences and similarities between them.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

When should i compare and contrast, making effective comparisons, comparing and contrasting as a brainstorming tool, structuring your comparisons, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about comparing and contrasting.

Many assignments will invite you to make comparisons quite explicitly, as in these prompts.

- Compare the treatment of the theme of beauty in the poetry of William Wordsworth and John Keats.

- Compare and contrast in-class and distance learning. What are the advantages and disadvantages of each approach?

Some other prompts may not directly ask you to compare and contrast, but present you with a topic where comparing and contrasting could be a good approach.

One way to approach this essay might be to contrast the situation before the Great Depression with the situation during it, to highlight how large a difference it made.

Comparing and contrasting is also used in all kinds of academic contexts where it’s not explicitly prompted. For example, a literature review involves comparing and contrasting different studies on your topic, and an argumentative essay may involve weighing up the pros and cons of different arguments.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

As the name suggests, comparing and contrasting is about identifying both similarities and differences. You might focus on contrasting quite different subjects or comparing subjects with a lot in common—but there must be some grounds for comparison in the first place.

For example, you might contrast French society before and after the French Revolution; you’d likely find many differences, but there would be a valid basis for comparison. However, if you contrasted pre-revolutionary France with Han-dynasty China, your reader might wonder why you chose to compare these two societies.

This is why it’s important to clarify the point of your comparisons by writing a focused thesis statement . Every element of an essay should serve your central argument in some way. Consider what you’re trying to accomplish with any comparisons you make, and be sure to make this clear to the reader.

Comparing and contrasting can be a useful tool to help organize your thoughts before you begin writing any type of academic text. You might use it to compare different theories and approaches you’ve encountered in your preliminary research, for example.

Let’s say your research involves the competing psychological approaches of behaviorism and cognitive psychology. You might make a table to summarize the key differences between them.

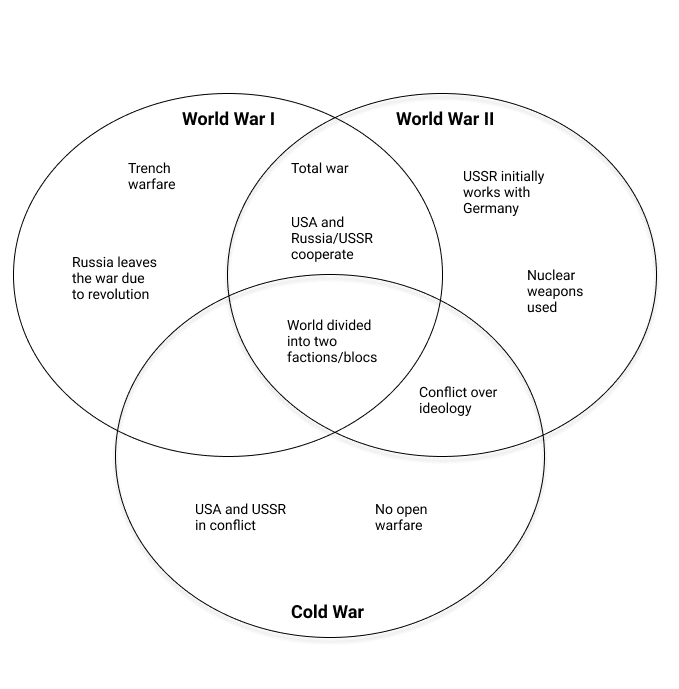

Or say you’re writing about the major global conflicts of the twentieth century. You might visualize the key similarities and differences in a Venn diagram.

These visualizations wouldn’t make it into your actual writing, so they don’t have to be very formal in terms of phrasing or presentation. The point of comparing and contrasting at this stage is to help you organize and shape your ideas to aid you in structuring your arguments.

When comparing and contrasting in an essay, there are two main ways to structure your comparisons: the alternating method and the block method.

The alternating method

In the alternating method, you structure your text according to what aspect you’re comparing. You cover both your subjects side by side in terms of a specific point of comparison. Your text is structured like this:

Mouse over the example paragraph below to see how this approach works.

One challenge teachers face is identifying and assisting students who are struggling without disrupting the rest of the class. In a traditional classroom environment, the teacher can easily identify when a student is struggling based on their demeanor in class or simply by regularly checking on students during exercises. They can then offer assistance quietly during the exercise or discuss it further after class. Meanwhile, in a Zoom-based class, the lack of physical presence makes it more difficult to pay attention to individual students’ responses and notice frustrations, and there is less flexibility to speak with students privately to offer assistance. In this case, therefore, the traditional classroom environment holds the advantage, although it appears likely that aiding students in a virtual classroom environment will become easier as the technology, and teachers’ familiarity with it, improves.

The block method

In the block method, you cover each of the overall subjects you’re comparing in a block. You say everything you have to say about your first subject, then discuss your second subject, making comparisons and contrasts back to the things you’ve already said about the first. Your text is structured like this:

- Point of comparison A

- Point of comparison B

The most commonly cited advantage of distance learning is the flexibility and accessibility it offers. Rather than being required to travel to a specific location every week (and to live near enough to feasibly do so), students can participate from anywhere with an internet connection. This allows not only for a wider geographical spread of students but for the possibility of studying while travelling. However, distance learning presents its own accessibility challenges; not all students have a stable internet connection and a computer or other device with which to participate in online classes, and less technologically literate students and teachers may struggle with the technical aspects of class participation. Furthermore, discomfort and distractions can hinder an individual student’s ability to engage with the class from home, creating divergent learning experiences for different students. Distance learning, then, seems to improve accessibility in some ways while representing a step backwards in others.

Note that these two methods can be combined; these two example paragraphs could both be part of the same essay, but it’s wise to use an essay outline to plan out which approach you’re taking in each paragraph.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

Some essay prompts include the keywords “compare” and/or “contrast.” In these cases, an essay structured around comparing and contrasting is the appropriate response.

Comparing and contrasting is also a useful approach in all kinds of academic writing : You might compare different studies in a literature review , weigh up different arguments in an argumentative essay , or consider different theoretical approaches in a theoretical framework .

Your subjects might be very different or quite similar, but it’s important that there be meaningful grounds for comparison . You can probably describe many differences between a cat and a bicycle, but there isn’t really any connection between them to justify the comparison.

You’ll have to write a thesis statement explaining the central point you want to make in your essay , so be sure to know in advance what connects your subjects and makes them worth comparing.

Comparisons in essays are generally structured in one of two ways:

- The alternating method, where you compare your subjects side by side according to one specific aspect at a time.

- The block method, where you cover each subject separately in its entirety.

It’s also possible to combine both methods, for example by writing a full paragraph on each of your topics and then a final paragraph contrasting the two according to a specific metric.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, July 23). Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay | Tips & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 15, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/compare-and-contrast/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write an expository essay, how to write an argumentative essay | examples & tips, academic paragraph structure | step-by-step guide & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Utility Menu

GA4 Tracking Code

Gen ed writes, writing across the disciplines at harvard college.

- Comparative Analysis

What It Is and Why It's Useful

Comparative analysis asks writers to make an argument about the relationship between two or more texts. Beyond that, there's a lot of variation, but three overarching kinds of comparative analysis stand out:

- Coordinate (A ↔ B): In this kind of analysis, two (or more) texts are being read against each other in terms of a shared element, e.g., a memoir and a novel, both by Jesmyn Ward; two sets of data for the same experiment; a few op-ed responses to the same event; two YA books written in Chicago in the 2000s; a film adaption of a play; etc.

- Subordinate (A → B) or (B → A ): Using a theoretical text (as a "lens") to explain a case study or work of art (e.g., how Anthony Jack's The Privileged Poor can help explain divergent experiences among students at elite four-year private colleges who are coming from similar socio-economic backgrounds) or using a work of art or case study (i.e., as a "test" of) a theory's usefulness or limitations (e.g., using coverage of recent incidents of gun violence or legislation un the U.S. to confirm or question the currency of Carol Anderson's The Second ).

- Hybrid [A → (B ↔ C)] or [(B ↔ C) → A] , i.e., using coordinate and subordinate analysis together. For example, using Jack to compare or contrast the experiences of students at elite four-year institutions with students at state universities and/or community colleges; or looking at gun culture in other countries and/or other timeframes to contextualize or generalize Anderson's main points about the role of the Second Amendment in U.S. history.

"In the wild," these three kinds of comparative analysis represent increasingly complex—and scholarly—modes of comparison. Students can of course compare two poems in terms of imagery or two data sets in terms of methods, but in each case the analysis will eventually be richer if the students have had a chance to encounter other people's ideas about how imagery or methods work. At that point, we're getting into a hybrid kind of reading (or even into research essays), especially if we start introducing different approaches to imagery or methods that are themselves being compared along with a couple (or few) poems or data sets.

Why It's Useful

In the context of a particular course, each kind of comparative analysis has its place and can be a useful step up from single-source analysis. Intellectually, comparative analysis helps overcome the "n of 1" problem that can face single-source analysis. That is, a writer drawing broad conclusions about the influence of the Iranian New Wave based on one film is relying entirely—and almost certainly too much—on that film to support those findings. In the context of even just one more film, though, the analysis is suddenly more likely to arrive at one of the best features of any comparative approach: both films will be more richly experienced than they would have been in isolation, and the themes or questions in terms of which they're being explored (here the general question of the influence of the Iranian New Wave) will arrive at conclusions that are less at-risk of oversimplification.

For scholars working in comparative fields or through comparative approaches, these features of comparative analysis animate their work. To borrow from a stock example in Western epistemology, our concept of "green" isn't based on a single encounter with something we intuit or are told is "green." Not at all. Our concept of "green" is derived from a complex set of experiences of what others say is green or what's labeled green or what seems to be something that's neither blue nor yellow but kind of both, etc. Comparative analysis essays offer us the chance to engage with that process—even if only enough to help us see where a more in-depth exploration with a higher and/or more diverse "n" might lead—and in that sense, from the standpoint of the subject matter students are exploring through writing as well the complexity of the genre of writing they're using to explore it—comparative analysis forms a bridge of sorts between single-source analysis and research essays.

Typical learning objectives for single-sources essays: formulate analytical questions and an arguable thesis, establish stakes of an argument, summarize sources accurately, choose evidence effectively, analyze evidence effectively, define key terms, organize argument logically, acknowledge and respond to counterargument, cite sources properly, and present ideas in clear prose.

Common types of comparative analysis essays and related types: two works in the same genre, two works from the same period (but in different places or in different cultures), a work adapted into a different genre or medium, two theories treating the same topic; a theory and a case study or other object, etc.

How to Teach It: Framing + Practice

Framing multi-source writing assignments (comparative analysis, research essays, multi-modal projects) is likely to overlap a great deal with "Why It's Useful" (see above), because the range of reasons why we might use these kinds of writing in academic or non-academic settings is itself the reason why they so often appear later in courses. In many courses, they're the best vehicles for exploring the complex questions that arise once we've been introduced to the course's main themes, core content, leading protagonists, and central debates.

For comparative analysis in particular, it's helpful to frame assignment's process and how it will help students successfully navigate the challenges and pitfalls presented by the genre. Ideally, this will mean students have time to identify what each text seems to be doing, take note of apparent points of connection between different texts, and start to imagine how those points of connection (or the absence thereof)

- complicates or upends their own expectations or assumptions about the texts

- complicates or refutes the expectations or assumptions about the texts presented by a scholar

- confirms and/or nuances expectations and assumptions they themselves hold or scholars have presented

- presents entirely unforeseen ways of understanding the texts

—and all with implications for the texts themselves or for the axes along which the comparative analysis took place. If students know that this is where their ideas will be heading, they'll be ready to develop those ideas and engage with the challenges that comparative analysis presents in terms of structure (See "Tips" and "Common Pitfalls" below for more on these elements of framing).

Like single-source analyses, comparative essays have several moving parts, and giving students practice here means adapting the sample sequence laid out at the " Formative Writing Assignments " page. Three areas that have already been mentioned above are worth noting:

- Gathering evidence : Depending on what your assignment is asking students to compare (or in terms of what), students will benefit greatly from structured opportunities to create inventories or data sets of the motifs, examples, trajectories, etc., shared (or not shared) by the texts they'll be comparing. See the sample exercises below for a basic example of what this might look like.

- Why it Matters: Moving beyond "x is like y but also different" or even "x is more like y than we might think at first" is what moves an essay from being "compare/contrast" to being a comparative analysis . It's also a move that can be hard to make and that will often evolve over the course of an assignment. A great way to get feedback from students about where they're at on this front? Ask them to start considering early on why their argument "matters" to different kinds of imagined audiences (while they're just gathering evidence) and again as they develop their thesis and again as they're drafting their essays. ( Cover letters , for example, are a great place to ask writers to imagine how a reader might be affected by reading an their argument.)

- Structure: Having two texts on stage at the same time can suddenly feel a lot more complicated for any writer who's used to having just one at a time. Giving students a sense of what the most common patterns (AAA / BBB, ABABAB, etc.) are likely to be can help them imagine, even if provisionally, how their argument might unfold over a series of pages. See "Tips" and "Common Pitfalls" below for more information on this front.

Sample Exercises and Links to Other Resources

- Common Pitfalls

- Advice on Timing

- Try to keep students from thinking of a proposed thesis as a commitment. Instead, help them see it as more of a hypothesis that has emerged out of readings and discussion and analytical questions and that they'll now test through an experiment, namely, writing their essay. When students see writing as part of the process of inquiry—rather than just the result—and when that process is committed to acknowledging and adapting itself to evidence, it makes writing assignments more scientific, more ethical, and more authentic.

- Have students create an inventory of touch points between the two texts early in the process.

- Ask students to make the case—early on and at points throughout the process—for the significance of the claim they're making about the relationship between the texts they're comparing.

- For coordinate kinds of comparative analysis, a common pitfall is tied to thesis and evidence. Basically, it's a thesis that tells the reader that there are "similarities and differences" between two texts, without telling the reader why it matters that these two texts have or don't have these particular features in common. This kind of thesis is stuck at the level of description or positivism, and it's not uncommon when a writer is grappling with the complexity that can in fact accompany the "taking inventory" stage of comparative analysis. The solution is to make the "taking inventory" stage part of the process of the assignment. When this stage comes before students have formulated a thesis, that formulation is then able to emerge out of a comparative data set, rather than the data set emerging in terms of their thesis (which can lead to confirmation bias, or frequency illusion, or—just for the sake of streamlining the process of gathering evidence—cherry picking).

- For subordinate kinds of comparative analysis , a common pitfall is tied to how much weight is given to each source. Having students apply a theory (in a "lens" essay) or weigh the pros and cons of a theory against case studies (in a "test a theory") essay can be a great way to help them explore the assumptions, implications, and real-world usefulness of theoretical approaches. The pitfall of these approaches is that they can quickly lead to the same biases we saw here above. Making sure that students know they should engage with counterevidence and counterargument, and that "lens" / "test a theory" approaches often balance each other out in any real-world application of theory is a good way to get out in front of this pitfall.

- For any kind of comparative analysis, a common pitfall is structure. Every comparative analysis asks writers to move back and forth between texts, and that can pose a number of challenges, including: what pattern the back and forth should follow and how to use transitions and other signposting to make sure readers can follow the overarching argument as the back and forth is taking place. Here's some advice from an experienced writing instructor to students about how to think about these considerations:

a quick note on STRUCTURE

Most of us have encountered the question of whether to adopt what we might term the “A→A→A→B→B→B” structure or the “A→B→A→B→A→B” structure. Do we make all of our points about text A before moving on to text B? Or do we go back and forth between A and B as the essay proceeds? As always, the answers to our questions about structure depend on our goals in the essay as a whole. In a “similarities in spite of differences” essay, for instance, readers will need to encounter the differences between A and B before we offer them the similarities (A d →B d →A s →B s ). If, rather than subordinating differences to similarities you are subordinating text A to text B (using A as a point of comparison that reveals B’s originality, say), you may be well served by the “A→A→A→B→B→B” structure.

Ultimately, you need to ask yourself how many “A→B” moves you have in you. Is each one identical? If so, you may wish to make the transition from A to B only once (“A→A→A→B→B→B”), because if each “A→B” move is identical, the “A→B→A→B→A→B” structure will appear to involve nothing more than directionless oscillation and repetition. If each is increasingly complex, however—if each AB pair yields a new and progressively more complex idea about your subject—you may be well served by the “A→B→A→B→A→B” structure, because in this case it will be visible to readers as a progressively developing argument.

As we discussed in "Advice on Timing" at the page on single-source analysis, that timeline itself roughly follows the "Sample Sequence of Formative Assignments for a 'Typical' Essay" outlined under " Formative Writing Assignments, " and it spans about 5–6 steps or 2–4 weeks.

Comparative analysis assignments have a lot of the same DNA as single-source essays, but they potentially bring more reading into play and ask students to engage in more complicated acts of analysis and synthesis during the drafting stages. With that in mind, closer to 4 weeks is probably a good baseline for many single-source analysis assignments. For sections that meet once per week, the timeline will either probably need to expand—ideally—a little past the 4-week side of things, or some of the steps will need to be combined or done asynchronously.

What It Can Build Up To

Comparative analyses can build up to other kinds of writing in a number of ways. For example:

- They can build toward other kinds of comparative analysis, e.g., student can be asked to choose an additional source to complicate their conclusions from a previous analysis, or they can be asked to revisit an analysis using a different axis of comparison, such as race instead of class. (These approaches are akin to moving from a coordinate or subordinate analysis to more of a hybrid approach.)

- They can scaffold up to research essays, which in many instances are an extension of a "hybrid comparative analysis."

- Like single-source analysis, in a course where students will take a "deep dive" into a source or topic for their capstone, they can allow students to "try on" a theoretical approach or genre or time period to see if it's indeed something they want to research more fully.

- DIY Guides for Analytical Writing Assignments

- Types of Assignments

- Unpacking the Elements of Writing Prompts

- Formative Writing Assignments

- Single-Source Analysis

- Research Essays

- Multi-Modal or Creative Projects

- Giving Feedback to Students

Assignment Decoder

- Writing Home

- Writing Advice Home

The Comparative Essay

- Printable PDF Version

- Fair-Use Policy

What is a comparative essay?

A comparative essay asks that you compare at least two (possibly more) items. These items will differ depending on the assignment. You might be asked to compare

- positions on an issue (e.g., responses to midwifery in Canada and the United States)

- theories (e.g., capitalism and communism)

- figures (e.g., GDP in the United States and Britain)

- texts (e.g., Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Macbeth )

- events (e.g., the Great Depression and the global financial crisis of 2008–9)

Although the assignment may say “compare,” the assumption is that you will consider both the similarities and differences; in other words, you will compare and contrast.

Make sure you know the basis for comparison

The assignment sheet may say exactly what you need to compare, or it may ask you to come up with a basis for comparison yourself.

- Provided by the essay question: The essay question may ask that you consider the figure of the gentleman in Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations and Anne Brontë’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall . The basis for comparison will be the figure of the gentleman.

- Developed by you: The question may simply ask that you compare the two novels. If so, you will need to develop a basis for comparison, that is, a theme, concern, or device common to both works from which you can draw similarities and differences.

Develop a list of similarities and differences

Once you know your basis for comparison, think critically about the similarities and differences between the items you are comparing, and compile a list of them.

For example, you might decide that in Great Expectations , being a true gentleman is not a matter of manners or position but morality, whereas in The Tenant of Wildfell Hall , being a true gentleman is not about luxury and self-indulgence but hard work and productivity.

The list you have generated is not yet your outline for the essay, but it should provide you with enough similarities and differences to construct an initial plan.

Develop a thesis based on the relative weight of similarities and differences

Once you have listed similarities and differences, decide whether the similarities on the whole outweigh the differences or vice versa. Create a thesis statement that reflects their relative weights. A more complex thesis will usually include both similarities and differences. Here are examples of the two main cases:

While Callaghan’s “All the Years of Her Life” and Mistry’s “Of White Hairs and Cricket” both follow the conventions of the coming-of-age narrative, Callaghan’s story adheres more closely to these conventions by allowing its central protagonist to mature. In Mistry’s story, by contrast, no real growth occurs.

Although Darwin and Lamarck came to different conclusions about whether acquired traits can be inherited, they shared the key distinction of recognizing that species evolve over time.

Come up with a structure for your essay

Note that the French and Russian revolutions (A and B) may be dissimilar rather than similar in the way they affected innovation in any of the three areas of technology, military strategy, and administration. To use the alternating method, you just need to have something noteworthy to say about both A and B in each area. Finally, you may certainly include more than three pairs of alternating points: allow the subject matter to determine the number of points you choose to develop in the body of your essay.

When do I use the block method? The block method is particularly useful in the following cases:

- You are unable to find points about A and B that are closely related to each other.

- Your ideas about B build upon or extend your ideas about A.

- You are comparing three or more subjects as opposed to the traditional two.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Mentor Texts

Writing Comparative Essays: Making Connections to Illuminate Ideas

Breathing new life into a familiar school format, with the help of Times journalism and several winning student essays.

By Katherine Schulten

Our new Mentor Text series spotlights writing from The Times and from our student contests that teenagers can learn from and emulate.

This entry aims to help support those participating in our Third Annual Connections Contest , in which students are invited to take something they are studying in school and show us, via parallels found in a Times article, how it connects to our world today. In other words, we’re asking them to compare ideas in two texts.

For even more on how to help your students make those kinds of connections, please see our related writing unit .

I. Overview

Making connections is a natural part of thinking. We can’t help doing it. If you’re telling a friend about a new song or restaurant or TV show you like, you’ll almost always find yourself saying, “It’s like _________” and referencing something you both know. It’s a simple way of helping your listener get his or her bearings.

Journalists do it too. In fact, it’s one of the main tools of the trade to help explain a new concept or reframe an old one. Here are just a few recent examples:

A science reporter explains the behavior of fossilized marine animals by likening them to humans making conga lines.

A sportswriter describes the current N.B.A. season by framing it in terms of Broadway show tunes.

An Op-Ed contributor compares today’s mainstreaming of contemporary African art to “an urban neighborhood undergoing gentrification.”

Sometimes a journalist will go beyond making a simple analogy and devote a whole piece to an extended comparison between two things. Articles like these are real-world cousins of that classic compare/contrast essay you’ve probably been writing in school since you could first hold a pen.

For example, take a look at how each of the Times articles below focuses on a comparison, weaving back and forth between two things and looking at them from different angles:

Consider a classic sports debate: Jordan vs. James. See how this 2016 piece explores what the two have in common — as well as how they differ.

Or, check out this 2019 piece that argues that “ Friendsgiving Has Become Just as Fraught as Thanksgiving ,” and compares the two to determine which has become “a bigger pain in the wishbone.”

Though written as a list rather than an essay, this fun piece from the Watching section in 2018 contends that “ ‘Die Hard’ Never Died, It Just Turned 30 and Had Cinematic Children ” by comparing the original to heirs like “Speed” and “Home Alone.” Read it to notice how, in just a paragraph per movie, the writer still manages to provide plenty of evidence to make each comparison work.

To find real-world examples that are closer to what you’re asked to do in school, look to Times sections that feature in-depth writing, like the Sunday Review and the Times Magazine . Both often publish pieces that connect some aspect of the past to an event, issue or trend today. For example:

“ What Quakers Can Teach Us About the Politics of Pronouns ” suggests lessons for “today’s egalitarians” by making a link to the 17th-century Quakers, “who also suspected that the rules of grammar stood between them and a society of equals.”

Other recent pieces focus on historical comparisons, including “ Early Motherhood Has Always Been Miserable ,” “ Donald Trump, Meet Your Precursor ” and a satirical video Op-Ed, “ Here’s What Cancel Culture Looked Like in 1283 .”

The 1619 Project , a Times Magazine initiative observing the 400th anniversary of the beginning of American slavery, is an especially rich example of this kind of connection-making. It reframes American history by “placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of the story we tell ourselves about who we are” — and uses that frame to look at issues including today’s prison system, health care, the wealth gap, the sugar industry and traffic jams in Atlanta.

Now, are all of these pieces structured exactly like that essay you have to write for your English class comparing a contemporary work to “Romeo and Juliet?” Does each have a clear thesis statement in the last line of the first paragraph and three body paragraphs that begin with topic sentences?

Of course not. They were written for an entirely different audience and purpose than the essay you might have to write, and most of them resist easy categorization into a specific “text type.”

But these pieces are full of craft lessons that can make your own writing more artful and interesting. And if you are participating in our annual Connections Contest , the essays we feature below will be especially helpful, since they focus on doing just what you’ll be doing — making a comparison between something you’re studying in school and some event, issue, trend, person, problem or concept in the news today.

First you’ll consider one excellent Times essay that does pretty much exactly what we’re asking you to do.

Next, we’ve supplied examples from over a dozen previous student winners to help guide you through the basic elements of any comparative analysis. Whether you’re writing for our contest or not, we hope you’ll find plenty of strategies to borrow.

II. Looking at Structure Over All: One Times Mentor Text

Take a look at the essay the Times book critic Michiko Kakutani wrote in the first weeks of the Trump administration. Just as many of you will do for our contest, she examines how a classic literary work can take on new significance when considered in light of real-world events.

Whether you agree with her analysis or not, notice how “ Why ‘1984’ Is a 2017 Must-Read ” is structured. You might highlight three categories — places where she’s writing chiefly about “1984”; places where she’s writing chiefly about our world today; and places where the two merge.

Here is how her piece, a Critic’s Notebook essay, begins:

The dystopia described in George Orwell’s nearly 70-year-old novel “1984” suddenly feels all too familiar. A world in which Big Brother (or maybe the National Security Agency) is always listening in, and high-tech devices can eavesdrop in people’s homes. (Hey, Alexa, what’s up?) A world of endless war, where fear and hate are drummed up against foreigners, and movies show boatloads of refugees dying at sea. A world in which the government insists that reality is not “something objective, external, existing in its own right” — but rather, “whatever the Party holds to be truth is truth.”

How does the first line set up the comparison?

How does the writer weave back and forth between today’s world and the world of “1984”? For example, what is she doing the two times she uses parentheses?

After you read the full essay, you might then consider:

Over all, what did you notice about the structure of this piece? How does it emphasize the parallels between the world of “1984” and the world of January 2017?

Is it effective? What is this writer’s thesis? Does she make her case, in your opinion? What specific lines, or points of comparison, do that especially well?

What transitional words and phrases does the writer use to move between her two topics? For example, in the second paragraph she writes “It was a phrase chillingly reminiscent …” as a bridge. What other examples can you find?

How does she sometimes merge her two topics — for example in the phrase “make Oceania great again”?

What else do you notice or admire about this review? What lessons might it have for your writing?

III. Elements of Effective Comparative Analyses: Great Examples From Students

Our Connections Contest asks students to find and analyze parallels, just as Ms. Kakutani does in her essay on Orwell — though she had some 1,200 words to build a case and students participating in our contest have only 450.

But if you look at the examples below from our 2017 and 2018 winners, you’ll see that it’s possible to make a rich connection in just a few paragraphs, and you’ll find plenty of specific strategies to borrow in constructing your own.

Here are some tips, with student examples to illustrate each.

1. Make sure you’re focusing on a manageable theme or idea.

One of the first ways to get on the wrong track in writing a comparative essay is to take on something too big for the scope of the assignment. Say, for example, you’re studying the Industrial Revolution and you realize you can compare it to today’s digital revolution in an array of ways, including worker’s rights, the upheaval of traditional industries and the impact on everyday lives. Where do you even begin?

That’s more or less the problem Alex Iyer, a student winner of our 2018 contest, had after reading “The Odyssey” in class, and noticing connections between the tale of that famous wanderer and today’s global refugee crisis. What can you possibly say in 450 words to connect two enormous topics, both of which have been the subject of innumerable scholarly books?

Notice how this student focuses. Instead of starting with a broad thesis like “We can see many parallels between the themes of ‘The Odyssey’ and our world today,” he looks only at how the Greek concept of xenia echoes today — and does so by examining just one article about Uganda. Below are the first two paragraphs, but we suggest you read the entire essay , paying close attention to how he describes both texts solely through this lens.

Try this: Once you choose a manageable focus, make sure all your details and examples support it.

Example: Alex Iyer, Geneva School of Boerne, San Antonio: Homer’s “The Odyssey” and “ As Rich Nations Close the Door on Refugees, Uganda Welcomes Them ”

In literature, we learned that in Homer’s epic poem “The Odyssey,” Homer uses the tribulations of the hero Odysseus to illustrate the Ancient Grecian custom of xenia. This custom focused on extending hospitality to those who found themselves far from home. As Odysseus navigates the treacherous path back to his own home, he encounters both morally upstanding and malevolent individuals. They range from a charitable princess who offers food and clothing, to an evil Cyclops who attempts to murder the hero and his fellow men. In class, we agreed that Homer employs these contrasting characters to exemplify not only proper, but also poor forms of xenia. For the people of its time, “The Odyssey” cemented the idea that xenia was fundamental for good character, resulting in hospitality becoming ingrained in the fabric of Ancient Grecian society. I saw a parallel to this in a New York Times article called “As Rich Nations Close the Door on Refugees, Uganda Welcomes Them” published on October 28, 2018. Similar to the prevalent custom of xenia in Ancient Greece, Uganda has made hosting refugees a national policy. The country is now occupied by up to 1.25 million refugees, many of whom are fleeing the violent unrest of South Sudan.

2. Introduce and briefly explain the significance of the connection.

We know it’s tempting to resort to a generic statement like, “In this essay I will compare and contrast _________ and _________ to show that …”

Not only is that deadly dull, but if you are participating in our contest, you also don’t want to waste any of your 450 words on a sentence that doesn’t say much.

Consider, instead, four more powerful ways to introduce the two things you’ll be connecting, and show right away how they work together.

Try this: Pose a question or questions that both texts are asking.

Example: Connor Stevens, Sunset High School, Portland, Ore.: Comparing “Fahrenheit 451” by Ray Bradbury and “ How Egypt Crowdsources Censorship ” ( Read the full student essay .)

How can you control ideas? In today’s world, you scroll through feeds, finding any information available: government trade deals, local restaurants, movies, and TV shows. We are in an age where the power to find any fact, answer or piece of information that floats into question is available anywhere. If this privilege was stripped by a bodying government, how would freedom of information change?

Try this: Make a statement that is true for both, and then explain why briefly.

Example: Jack Magner, Flint Hill School, Oakton, Va.: Comparing biological feedback loops and homeostasis with “ After #MeToo, the Ripple Effect ” ( Read the full student essay .)

All it takes is a single action to spark innumerable reactions. In the case of Jessica Bennett’s “After #MeToo, the Ripple Effect,” it is the publishing of a 2017 article in the Times that launches a revolution, changing the treatment and recognition of women for the better. In the case of AP Biology, it is the connection of a ligand to a receptor protein or a drastic change to an organism’s environment that sends millions of signals that protect the organism from harm.

Try this: Explain how or why you’ll look at a classic work through a new lens.

Example: Zaria Roller, Verona Area High School, Wis.: Comparing “Things Fall Apart” by Chinua Achebe and “ The Boys Are Not All Right ” ( Read the full student essay .)

Colonial-age Nigeria and modern day Western society have more in common than one would think. Although the buzz phrase “toxic masculinity” did not exist at the time Chinua Achebe’s “Things Fall Apart” was written, its protagonist, Okonkwo, might as well be the poster boy for it.

Try this: Trace your thinking about how you came to connect the two things. Please note: For this contest, use of the word “I” is not only permitted but also encouraged if it helps you explore your ideas.

Example: Alexa Bolnick, Indian Hills High School, Franklin Lakes, N.J.: “Death of a Salesman” by Arthur Miller and “ A Lack of Respect for the Working Class in America Today ” ( Read the full student essay .)

Last year, reading the play “Death of a Salesman,” I couldn’t understand why salesman Willy Loman refused to accept his son’s desire to perform manual labor for a living. If working on a ranch made him happy, then why couldn’t Willy let his son go.

Example: Isabella Picillo, 17, Oceanside High School: “The Scarlet Letter” and “ Judge Partially Lifts Trump Administration Ban on Refugees ” ( Read the full student essay .)

I stumble upon a New York Times article, “Judge Partially Lifts Trump Administration Ban on Refugees,” that makes me wonder if Hawthorne, the literary genius, is wrong.

3. Use transition words and phrases to pivot between the two works.

When you’re discussing two works in the same piece, you’ll find yourself needing to switch gears regularly. How do you do that gracefully?

Try this: Explore a connection by choosing transition words that emphasize commonality.

Here are some sentences, all from our 2018 winners , with examples of those words in bold:

— “ Similar to the prevalent custom of xenia in Ancient Greece, Uganda has made hosting refugees a national policy.” — “John Steinbeck’s classic novel ‘The Grapes of Wrath,’ which chronicles the struggles of the Joad family during the Great Depression, documents a similar reality.” — “Republican anti-Trump attitudes echo those of their nineteenth century counterparts, such as Carl Schulz, who wrote, ‘Our duty to the country … is … paramount to any duty we may owe to the party.’” — “ Paralleling the same theme, the short story ‘Harrison Bergeron’ by Kurt Vonnegut describes a future in which absolute equality has become the obsession of society.” — “This phenomenon mirrors that of negative feedback loops in biology, in which a stimulus triggers a biological response designed to keep a biological system at equilibrium.”

4. Acknowledge important contrasts between the two things you are connecting.

Part of comparing two things is contrasting them — showing where the commonalities end and explaining why the differences are significant.

But your essay shouldn’t just be a list of all the things the two texts have in common vs. all the things they don’t. Instead, you need to use the contrasts to acknowledge obvious differences, but still further your point about how and why the two ideas work together.

For example, the article comparing LeBron James and Michael Jordan makes the crucial distinction that they played in different eras — and thus it’s hard to compare them since we remember Jordan through “rose-colored” memories, while James, playing today, is considered by many “the most scrutinized and criticized American athlete, much of the naysaying unwarranted and aggravated by the polarizing effects of social media” that didn’t exist in Jordan’s heyday.

Keep in mind that since our contest emphasizes connections, not all of our previous winners have done this — but those who did only strengthened their cases.

Try this: Point out that surface differences are less important than the underlying message.

Example: Megan Lee, West Windsor Plainsboro High School North, Plainsboro, N.J.: “Harrison Bergeron” by Kurt Vonnegut and “ The Curse of Affirmative Action ” ( Read the full student essay .)

Although the “Harrison Bergeron” is a heavily exaggerated piece of fiction writing while “The Curse of Affirmative Action” was written to denounce a real world policy, both allude to the delicacy of equality.

Try this: Use a contrast to illuminate a bigger point — in this case that the ways in which the #MeToo movement is different than a biological feedback loop is also what makes it so “revolutionary.”

Example: Jack Magner, Flint Hill School, Oakton, Va.: Biological feedback loops and homeostasis and “ After #MeToo, the Ripple Effect ” ( Read the full student essay .)

#MeToo and feedback loops are extremely interconnected, but there is one key difference in the #MeToo movement that makes it so dynamic and revolutionary. In biology, feedback responses are developed slowly and organically over millions of years of evolution. Environments select for these responses, and a species’s fitness increases as a result. The #MeToo movement is the exact opposite, attacking the perceived natural order that our environment has selected for at the expense the “fittest” members of society: powerful men. This positive feedback loop does not run in concurrence with the already-established negative feedback loop. It instead serves as its foil, aiming to topple the destructive systems for which hyper-masculine society has selected for over thousands of years.

5. End in a way that sums up and says something new.

We could repeat this piece of advice in every edition of our Mentor Text series regardless of genre: No matter what you’re writing about, don’t waste your conclusion by just lazily restating what you’ve already said.

Instead, keep your readers thinking. Pose a new question, use a fresh quote that sums up your main idea, give some surprising new information, or tell a fitting final story.

In other words, no “In conclusion, I have shown how _________ and _________ have many similarities and many differences.”

Instead you could …

Try this: Draw a final lesson, takeaway or “moral” that the two together express.

Example: Samantha Jones, 16, Concord Carlisle Regional High School: “Walden” and “ Dropping Out of College Into Life ” ( Read the full student essay .)

The moral is clear: there are gaps in our education system, and because of these gaps students aren’t adequately prepared for their own futures. In his book Walden, Thoreau elaborates on the ideas Stauffer touches on in her article. As stated before, he believed learning through experience was exponentially better than a in classroom. When a rigid curriculum with expectations is set in place, students aren’t given the same hands on learning as they would be without one. Just as Stauffer embraced this learning style in the New School, Thoreau did so in Walden Woods …

Example: Robert McCoy, Whippany Park High School, Whippany, N.J.: Gilded Age Mugwumps and “ Republicans for Democrats ” ( Read the full student essay .)

The parallels in the Mugwump and Never Trump movements demonstrate the significance of adhering to a strict moral standard, despite extreme partisan divides …

Try this: Raise a new question or idea suggested by the comparison.

In this essay, Sebastian Zagler compares the ways that both a famous mathematical problem and the issue of climate change will require new innovation and collaboration to solve. But he ends the essay by engaging a new, related question: Why would anyone want to take on such “impossible problems” in the first place?

Example: Sebastian Zagler, John T. Hoggard High School, Wilmington, N.C.: the Collatz, or 3n+1, conjecture, a mathematical problem that has produced no mathematical proof for over 80 years, and “ Stopping Climate Change Is Hopeless. Let’s Do It. ” ( Read the full student essay .)

What draws mankind to these impossible problems, whether it be solving the Collatz conjecture or reversing climate change? Fighting for a common cause brings people together, making them part of something greater. Even fighting a “long defeat” can give one a sense of purpose — a sense of belonging …

Try this: End with an apt quote that applies to both.

Here are Sebastian Zagler’s last two lines:

There is a beauty in fighting a losing battle, as long as a glimmer of hope remains. And as Schendler and Jones write, “If the human species specializes in one thing, it’s taking on the impossible.”

And here are Samantha Jones’s:

For that is all Walden really is; Thoreau learning from nature by immersing himself in it, instead of seeing it on the pages of a book. A quote from Walden most fitting is as follows, “We boast of our system of education, but why stop at schoolmasters and schoolhouses? We are all schoolmasters, and our schoolhouse is the universe”

In both cases, the quotes are inspiring, hopeful and get at truths their essays worked hard to demonstrate.

Additional Resources

In our description of Unit 3 of our writing curriculum you can find much, much more, including related writing prompts and a series of lesson plans that can help teachers teach with our Connections Contest.

Instructor Resources

Comparative essay.

Compare two or more literary works that we have studied in this class. Your comparative essay should not only compare but also contrast the literary texts, addressing the similarities and differences found within the texts.

Step 1: Identify the Basis for Comparison

Identify the basis of comparison. In other words, what aspect of the literature will you compare? (Theme, tone, point of view, setting, language, etc.)

Step 2: Create a List of Similarities and Differences

Carefully examine the literary texts for similarities and difference using the criteria you identified in step 1.

Step 3: Write a Thesis Statement

A thesis statement is the author’s educated opinion that can be defended. For a comparative essay, your thesis statement should assert why the similarities and differences between the literary works matter.

Step 4: Create a Structure

Before drafting, create an outline. Your introduction should draw the reader in and provide the thesis statement. The supporting paragraphs should begin with a topic sentence that supports your thesis statement; each topic sentence should then be supported with textual evidence. The conclusion should summarize the essay and prompt the reader to continue thinking about the topic.

Word Count: approximately 1500 words

Outside Sources needed: none (but use plenty of textual evidence)

- Comparative Essay. License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

Comparative Essays

Writing a comparison usually requires that you assess the similarities and differences between two or more theories, procedures, or processes. You explain to your reader what insights can be gained from the comparison, or judge whether one thing is better than another according to established criteria.

How to Write a Comparative Essay

1. Establish a basis of comparison

A basis of comparison represents the main idea, category, or theme you will investigate. You will have to do some preliminary reading, likely using your course materials, to get an idea of what kind of criteria you will use to assess whatever you are comparing. A basis of comparison must apply to all items you are comparing, but the details will be different.

For example, if you are asked to “compare neoclassical architecture and gothic architecture,” you could compare the influence of social context on the two styles.

2. Gather the details of whatever you are comparing

Once you have decided what theme or idea you are investigating, you will need to gather details of whatever you are comparing, especially in terms of similarities and differences. Doing so allows you to see which criteria you should use in your comparison, if not specified by your professor or instructor.

- Appeal to Greek perfection

- Formulaic and mathematical

- Appeal to emotion

- Towers and spires

- Wild and rustic

- Civic buildings

Based on this information, you could focus on how ornamentation and design principles reveal prevailing intellectual thought about architecture in the respective eras and societies.

3. Develop a thesis statement

After brainstorming, try to develop a thesis statement that identifies the results of your comparison. Here is an example of a fairly common thesis statement structure:

e.g., Although neoclassical architecture and gothic architecture have [similar characteristics A and B], they reveal profound differences in their interpretation of [C, D, and E].

4. Organize your comparison

You have a choice of two basic methods for organizing a comparative essay: the point-by-point method or the block method.

The point-by-point method examines one aspect of comparison in each paragraph and usually alternates back and forth between the two objects, texts, or ideas being compared. This method allows you to emphasize points of similarity and of difference as you proceed.

In the block method, however, you say everything you need to say about one thing, then do the same thing with the other. This method works best if you want readers to understand and agree with the advantages of something you are proposing, such as introducing a new process or theory by showing how it compares to something more traditional.

Sample Outlines for Comparative Essays on Neoclassical and Gothic Architecture

Building a point-by-point essay.

Using the point-by-point method in a comparative essay allows you to draw direct comparisons and produce a more tightly integrated essay.

1. Introduction

- Introductory material

- Thesis: Although neoclassical and gothic architecture are both western European forms that are exemplified in civic buildings and churches, they nonetheless reveal through different structural design and ornamentation, the different intellectual principles of the two societies that created them.

2. Body Sections/Paragraphs

- Ornamentation in Text 1

- Ornamentation in Text 2

- Major appeal in Text 1

- Major appeal in Text 2

- Style in Text 1

- Style in Text 2

3. Conclusion

- Why this comparison is important?

- What does this comparison tell readers?

Building a Block Method Essay

Using the block method in a comparative essay can help ensure that the ideas in the second block build upon or extend ideas presented in the first block. It works well if you have three or more major areas of comparison instead of two (for example, if you added in a third or fourth style of architecture, the block method would be easier to organize).

- Thesis: The neoclassical style of architecture was a conscious rejection of the gothic style that had dominated in France at the end of the middle ages; it represented a desire to return to the classical ideals of Greece and Rome.

- History and development

- Change from earlier form

- Social context of new form

- What does the comparison reveal about architectural development?

- Why is this comparison important?

Comparative Literature Essay

When you hear the words comparative and literature in one sentence, what do you mostly think about? Do words comparing two or more literary works come to mind? What about if you add the word essay to the mix? Do you think it means comparing two or more literary works from different points of views and writing it down in the form of an essay and stating your opinion about it? If you ask yourself these types of questions and want to know the answers, why don’t you check this one out?

3+ Comparative Literature Essay Examples

1. comparative literature essay template.

Size: 154 KB

2. Sample Comparative Literature Essay

3. Comparative Literature Essay Example

Size: 198 KB

4. Printable Comparative Literature Essay

Size: 98 KB

The Definition for Comparative

Defining the term comparative, this means to compare two or more things with each other. Compare, to consider the difference, to connect two things to each other.

The Description for Comparative Literature

This essay gives the writer the task to compare two or more literary works from the same writer. To compare the arguments, theories, events and the plot from different people’s points of view. Typically a comparative literary essay asks you to write and compare different literary genres and add your opinion about it. Of course this takes extensive research on the part of the writer as well.

Use of Comparative Literature

The use of a comparative literature essay for either a job, for education or for a journal is to expound on comparing two or more literary works and give out your explanation for the works you choose to talk about. More often than not, these types of literary essays are translated from different languages to the language you speak. It is also quite difficult to compare two literary works being criticized by different writers. This uses more analytical techniques than most essays.

Tips to Write a Good Comparative Literature Essay

As this is a type of essay that deals with comparing more than two literary genres and stories together, it may come off as difficult. But that issue has a solution as well. Here are some tips to help you write out a good comparative literature essay either for your class, a journal or for your job. This type of essay can also be helpful in practicing your comparing skills.

- Choose two topics: As this is to compare two or more literary pieces, choose the topic. Also choose two different people who are talking about the topic you choose.

- Do Research: Continuing from the first tip, do your research on each of the writer’s point of view . What do they think about the topic they wrote about? Who are you going to agree and disagree on? Your research will also help you make your own choice and write about it.

- Weigh each compared text as equal as possible: You may choose a side when writing this but also as you are comparing, weigh each subtopic you found in your research as equal as possible. Give a few opinions here and there but stick to the researched facts as well as focusing on the similarities of the two articles and their differences.

- Watch out for grammatical errors, misspelled words and incorrect punctuations: Just like any other essay you write, watch your spelling and grammar. Put the correct punctuations in the right place.

- Revision is key: Once you are done, revise anything that needs to be revised. Check everything if you have the right information in place.

How many topics do I need to compare?

Choose one literary writing. Do some research on what other writers say about the literary writing you chose and compare what they have written.

How many paragraphs do I need to write this type of essay?

3 full paragraphs. The first would be your introduction to the topic you are going to be comparing to, the second which is the body consists of weighing each of the text, comparing and contrast. The last paragraph is your conclusion.

Should I cite some of the research that I did on my essay?

Whether you are using the quotation of the writers you searched for, always cite where you seen it, and the date. This is to avoid plagiarism.

How many words does this essay take?

60,000 and 75,000 if you are making more than one essay.

This type of essay can be tricky compared to the rest of the essays. But with extensive research and practice, you are sure to write and compare the same way as most professionals are able to do. Good Luck!

Comparative Literature Essay Generator

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

Explore the theme of love in literature across two different cultures in a Comparative Literature Essay

Analyze how two authors from different periods address social injustice in a Comparative Literature Essay

- Food & Dining

- Coronavirus

- Real Estate

- Seattle History

- PNW Politics

How to Write Comparative Essays in Literature

- College & Higher Education

Related Articles

Thesis statements vs. main ideas, teacher tips: how to write thesis statements for high school papers, the types of outlining for writing research papers.

- Advantages of APA Writing Style

- What Are the Essential Parts of a College Essay?

A comparative essay is a writing task that requires you to compare two or more items. You may be asked to compare two or more literary works, theories, arguments or historical events. In literature, a comparative essay typically asks you to write an essay comparing two works by the same writer. For example, you may be asked to write a comparative essay comparing two plays written by William Shakespeare.

Although an essay may simply state to compare two literary texts, the assumption is that you should contrast the texts as well. In other words, your comparative essay should not only compare but also contrast the literary texts, it should address the similarities and differences found within the texts.

Identify the Basis for Comparison