- Reflective practice at Little Scholars: what it is, examples, and why it’s important

Reflective practice in early learning: what it is, examples, and why it’s important

- Little Scholars

- September 13, 2023

As early childhood educators, we encounter a variety of situations on a daily basis, ranging from ordinary to interesting (to say the least!). Reflective practice in early learning is about taking a step back and critically examining these experiences to better understand what happened and why. By reflecting on our practice, we can learn from our experiences, improve our approach, and ultimately provide better care for the children in our campuses.

Little Scholars provides an attractive and safe environment to children on the Gold Coast while giving you total peace of mind while your children are in our care. Learning areas include well-equipped playrooms and landscaped outdoor spaces for maximum learning opportunities. Book a tour today if you are looking for an early learning campus in South East Queensland.

What is reflective practice in early learning?

Reflective practice is a process of critical examination and evaluation of experiences, situations, and decisions to learn from them and improve future practice. It involves actively seeking out information, analysing and interpreting it, and using it to guide decision-making and improve outcomes. Reflective practice is not just about what happened, but also about why it happened and how it can be improved.

We apply reflective practice to various aspects of our work, such as planning, teaching, assessing, and communicating with children and families. It helps us identify the rationale behind our practices and evaluate whether they are consistent with our beliefs, values, and core philosophy .

Little Scholars School of Early Learning’s The Collective is a service-wide, multi-faceted educational initiative, designed to enhance each child’s learning and development and best support educators’ time spent with children.

The models of reflective practice in childcare

There are different types of reflective practice, including reflection-in-action, reflection-on-action, and reflection-for-action.

Reflection-in-action occurs spontaneously as we make decisions in response to what is happening in the moment.

Reflection-on-action involves thinking about experiences after the event and questioning how and why a specific practice contributed to or detracted from a child’s learning or relationships with families.

Reflection-for-action is a proactive way of thinking about future action and involves considering different approaches and refining inclusive practices and communication strategies to improve outcomes.

We view reflective practice as an essential component of developing a culture of learning that drives continuous improvement and focuses attention on quality outcomes for children and families. It helps us to enrich children’s learning, build our own knowledge and skills, and affirm and challenge our colleagues.

How to engage in reflective practice

To engage in reflective practice, we take time to observe children closely, foster relationships and gain insights into their thinking and learning. Here are some strategies we employ to engage in reflective practice in early learning:

- Review staffing arrangements and routines: We create an environment that is conducive to reflective practice by reviewing staffing arrangements and routines. This might include providing extended periods of uninterrupted time for educators to interact with small groups of children, foster closer relationships, and gain greater insight into children’s thinking and learning.

- Establish routines that allow for reflection: We regularly set aside time during scheduled programming or at the end of the day to record our reflections. Similarly, a similar amount of time can be allocated during a regularly scheduled meeting to reflect on practice across the service. These meetings can also provide a forum for team members to talk about their personal experiences.

- Work closely with experienced colleagues: We encourage our team to work closely with more experienced colleagues to provide opportunities to observe, critique, and learn from each other. They can describe what they noticed about a child’s response to an experience and ask questions about why their colleague used a particular strategy.

- Network with other services: Networking with other services can provide insights into the way the service is perceived by others. We meet with other people regularly in the wider community as we believe this provides opportunities to explore ways the service can become more responsive to the interests and needs of families and children in the local community.

Why is reflective practice important in early learning?

Reflective practice in early childhood education is important as it ensures educators regularly reflect on what they do, why they do it, and how this knowledge can improve their practice.

Studies show that high-quality early childhood settings positively affect children’s development, and reflective practice is a feature of such environments. This practice allows early childhood professionals to develop a critical understanding of our own practice and continually develop the necessary skills, knowledge and approaches to achieve the best outcomes for children.

Reflective practice also helps us create real opportunities for children to express their own thoughts and feelings and actively influence what happens in their lives. In addition, reflective practice helps professionals to develop a deeper awareness of their own prejudices, beliefs, and values, and advance learning for vulnerable children.

We value reflective practice at Little Scholars

At Little Scholars, we recognise the importance of reflective practice in providing high-quality early education to the children in our care. Our educators engage in regular reflection and are encouraged to share their insights and experiences with their colleagues.

We believe that by reflecting on our practice, we can continually improve and adapt to better meet the needs of the children and families we serve. The Collective allows for educators to have autonomy in how they document and plan for children. This supports a strength-based approach with our team.

If you live in South East Queensland, book a tour today to enrol your child in the best early learning campuses in the community.

At Little Scholars, our goal is to act as an extension of your family. Our first priority is the growth and development of your child; we nurture, teach and guide your child to developing all the skills that will allow them to succeed in life. It’s an approach that recognises how critical those first five years are for a child’s development, and ensures your child gets all the support they need to flourish during this time.

Get Started With Little Scholars Today!

At Little Scholars School of Early Learning, we’re dedicated to shaping bright futures and instilling a lifelong passion for learning. With our strategically located childcare centres in Brisbane and the Gold Coast, we provide tailored educational experiences designed to foster your child’s holistic development.

- Meet Our Founder

- Leadership Team

- Our Learning Philosophy

- Our Curriculum

- Learn & Play Studios

- What Families Say About Little Scholars

- Environment & Sustainability

- Stingless Bees Program

- Intergenerational Program

- Acknowledgement to Country

- Our 2036 Vision

- The Collective Curriculum

- Mindfulness

- Studio Tour

- Learning Environments

- Extra-curricular Programs

- Before & After School Care

- Outdoor Explorers

- Abecedarian Reading

- Family Time Program

- Supporting the Community

- Take Home Meals

- Be Involved

- Transition to School Program

- Parent Articles

- News & Media

- Childcare Subsidy

- Free Kindy at Little Scholars

- Child Safeguarding

- Redland bay

Let us hold your hand and help looking for a child care centre. Leave your details with us and we’ll be in contact to arrange a time for a ‘Campus Tour’ and we will answer any questions you might have!

" * " indicates required fields

Storypark Blog

Early childhood education insights

- Try Storypark for free

Reflective Practice in Early Childhood Education

Reflective practice in early childhood education – growing as educators and learners

Reflective practice in early childhood education has been described as a process of turning experience into learning. That is, of exploring experience in order to learn new things from it. Reflection involves taking the unprocessed, raw material of experience and engaging with it to make sense of what has occurred (Boud, D. 2001).

What is Reflective Practice?

Reflective practice supports you in making sense of a situation. It enables childcare professionals and teachers to grow and develop their own working theories, philosophy and pedagogy. For any educator, your reflections, both individual and team, provide valuable data and evidence of your developing pedagogy and professional growth.

As a teacher, manager, mentor and early childhood education facilitator, I believe we often use reflective practice throughout our working day. These daily reflections include anticipation of, during and after events. Reflections, or more importantly recording regular reflections is often an action that is overlooked due to the many demands placed on busy early childhood professionals.

Getting to the crux of true reflective practice – it’s more than just looking back! It’s about taking the time to think about values, assumptions and beliefs. It’s all very well to reflect by saying: “Well, we tried … and it didn’t work!”. What I have observed to be good reflective practice, is for early childhood educators to make time to work through these questions:

- What role have you played in this?

- What you did and why?

- How does this reflect the principles, and goals of our curriculum and our philosophy?

- What would you do differently to support a better outcome?

- What does this say about your teaching strategies and our role as educators?

Some educators may need support to strengthen their skills for deep reflective practice. This will allow them to truly unpack the inconsistencies between espoused beliefs and practices (what we think we do) versus actions in practice (what we really do). Reflective practice in early childhood education can support a greater understanding of who we are as teachers and how our own values and beliefs impact what we do and why.

Reflective Practice in Storypark

Using a reflection plan with goals within the Storypark planning area is ideal for assisting teachers in clarifying their ideas, musings, and evidence and can support deeper reflection. Sharing these reflections with fellow educators, colleagues and/or someone who is removed from the situation can provide external perspectives. It can be helpful as there is little benefit from being too insular and relying on just your own interpretations. The role of a “provocateur” can be a valuable one. A plan can be completely private or you can invite a mentor, manager or colleague from within your early childhood centre.

The evidence we gather in a plan or teacher story can provide a rich source for reflection. Yes, we have the stories we craft and create but we also have the data found within the reports area of your early childhood centre’s Storypark account and within your portfolio area. The learning tags you use provide learning trends that can highlight the learning you have focused on and recorded over any period of time. If you have used the learning tags to highlight the MAIN learning, then you will be able to create a picture of your own pedagogical focus . Also highlighting your lens on learning – what does it illuminate for you?

Reflection Models

Some examples of reflection models to support the creation of your own reflective practices:

Want to know more about using :

Learning Tags: https://intercom.help/storypark/general/learning-tags-and-sets/what-are-learning-tags-and-sets

Learning Trends Reports: https://intercom.help/storypark/for-teachers/reports/what-are-learning-trends

My Portfolio Report: https://intercom.help/storypark/for-teachers/teacher-portfolios/teacher-profile-reports

Planning: https://intercom.help/storypark/for-teachers/planning/create-a-plan

OʼConnor, A. & Diggins, C. (2002). On reflection: reflective practice for early childhood educators . Lower Hutt: Open Mind Publishing.

Campbell, Melenyzer, Nettles, & Wyman (2000). Portfolio and Performance Assessment in Teacher Education. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Brookfield, S. D. (1995). Becoming a critically reflective teacher. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Peters, J. (1991). Strategies for reflective practice. Professional development for Educators of Adults . New directions for Adult and Continuing Education . R. Brockett (ed). San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Boud, D. (2001). Using journal writing to enhance reflective practice. In English, L. M. and Gillen, M. A. (Eds.) Promoting Journal Writing in Adult Education . New Directions in Adult and Continuing Education No. 90. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 9-18.

Sharon Carlson, Professional Learning and Development Manager at Storypark

- Posted in: Educator Professional Development , Inspiration

- Tagged in: Educator Professional Learning

Posted by Sharon Carlson

Sharon's early years were supported at home by her Mum in Taranaki. She later became an ECE ICT facilitator for CORE Education, and then Storypark. Sharon has successfully supported the implementation of a diverse range of ICT products and services around the country and is helping make sure Storypark is awesome for teachers and children's development.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

Try Storypark for free and improve family engagement with children’s learning

[…] Reflective practice supports you in making sense of a situation and can enable you to grow and develop your own working theories, philosophy and pedagogy. Your reflections, both individual and team, provide valuable data and evidence of your developing pedagogy and professional growth. This article looks at reflective practice (both as an educator and a learner) and looks at a few reflection models to help you develop your own action plan. Get started here. […]

[…] thing. As educators, we belong to a profession that believes in the idea of lifelong learners. Self-reflection and professional goals help us achieve that. Not all learning needs to be a training course or a […]

[…] The mirror stands for reflective practice; […]

[…] will be considerably different from those who work with preschool-age children. Through the art of reflective practice, the simple notion of inquiring with the educators in your room may be enough to get the ball […]

[…] also helps to allow time for reflection, as well as the time needed to develop skills in a range of approaches to reflective practice – an example for this could be journal writing, critical conversation, and focus groups. The […]

[…] curricula and frameworks that place an importance on partnerships with parents and community, reflective practice, collaborative inquiry, educators as co-learners, pedagogical documentation, responsive […]

[…] process means we can sweep over what was occurring for children. It means we leave little room for reflection and can miss the deeper learning happening for […]

Reflection helps in making sense of the situation and understanding where one went wrong or did well and what we can do better. Reflection helps us learn new ways of solving and supporting children in development.

The lens model can be very helpful for children with special needs because if we are only looking from our perspective, we won’t realize that we could potentially be leaving children behind

Leave a reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

- Teach Early Years

- Teach Primary

- Teach Secondary

- Technology & Innovation

- Advertise With Us

- Free Reports

- Have You Seen

- Learning & Development

- A Unique Child

- Enabling Environments

- Positive Relationships

- Nursery Management

Home > Learning & Development

Learning and Development

Reflective practice in Early Years – How to use it in your setting

- Written By: Dr Helen Edwards

- Subject: Learning and development

Share this:

In this new educational era, we face a great deal of uncertainty, so reflective practice is needed now more than ever, says Dr Helen Edwards. Here are some tips to help you on your way…

Over the last few years we’ve all had to cope with new ways of working, adapting to a great deal of new guidance and operating in very different ways to those we are used to.

These changes require reflection so that we can all focus on what is working, adapt what isn’t and continue to grow and improve teaching and learning experiences for children.

I am sure that many practitioners have been busy thinking about a whole host of things - how roles and routines have changed; how resources are used and rotated; keeping staff safe and supported.

It may not feel like it, but much of this planning has probably included a large dose of reflective practice. Here are some practical ideas that you might want to implement.

Celebrate success

Reflection starts with a simple ‘taking stock’: the process of stepping back, thinking about what we have been doing, what has gone well, and what could be better.

Here are some helpful ‘taking stock’ questions:

- What area of our practice/environment are we going to focus on?

- What have we been doing?

- Who benefits from doing it this way? (Children, staff, families?)

- What has gone well?

- What needs improving and why?

- Who/what else do we need to think about?

- What can we keep/adapt to meet these needs?

- How are we going to do this? (You could include external CPD, in-house training, who will do what, when you will return to this area of reflection to see how things are going?)

Remember to celebrate all the things that have worked well. It’s so easy to slip into the treadmill of ‘what next?’ and a never-ending to do list.

Make sure you acknowledge the really good things, share with your colleagues and congratulate others.

Quick wins and active reflection

There will be areas where you feel things could be improved. Think about quick wins that would solve some immediate problems.

For example, what if you can’t think of a way for children to access all your resources safely. How do you choose which ones to use?

Is it easier to put into storage those resources that are just too hard to clean daily?

Sometimes reflective practice can sound like we need to tuck ourselves away in silence before we can even start. I don’t know any practitioners that can do that easily!

Instead, think about ‘active reflection’, something that can be part of your day-to-day practice.

- Be mindful Use your observations as a starting point. What can you see/hear? How do you feel? How might you be contributing, what influence are you having on the area you are thinking about?

- Make a quick record of your thoughts This could be in a notebook or using an online tool. Not only will this help you to remember what you are thinking, it will also create a timeline so you can record this reflective journey, big or small.

- Share with colleagues Whether your reflection is about your individual practice or about teaching and learning in the setting as a whole, it’s good to talk!

Using technology in reflective practice

Lockdown forced many of us to embrace the use of technology more fully. We saw this first hand at Tapestry where the number of videos and postings increased dramatically as practitioners devised new ways to support children’s learning at home.

As educators become more confident about technology, it can be used as a tool to benefit reflective practice too.

You could use video, perhaps with a voiceover to support your reflection. Visual and audio communication can be easier to share and feel more accessible to busy staff, and can require less explanation.

As we’ve all realised, technology can help us to stay connected. If a setting has staff who are shielding or needing to isolate, they could use Zoom, WhatsApp or Google Meet for meetings.

These would be inclusive, allowing all staff to have a voice in reflective practice.

Making the case for informal reflective practice

Another thing that lockdown underlined is the value of informal reflective practice.

For many, being at home and away from children was a real loss, but it also offered a chance for us to step back and think about what we might want to change ‘when we got back’.

I lost count of the number of chats I had with people about what they’d learnt during lockdown and how that might change what they did once settings opened to more children. In lots of cases these were fleeting thoughts.

I feel these fit into ‘informal reflective’ practice and they’re important to note. As reflective practitioners we need to learn to be alive to these and to capture them.

In this new educational era, we face a great deal of uncertainty. Developing our own routines for reflection, independently and with others, is more important than ever.

Many of us have honed these over the last few years. My view is that these are ‘skills for life’; valuable for us as professionals but also helpful throughout our lives.

Encouraging a culture of reflective practice

The ethos of a setting is at the heart of creating a culture of reflective practice. Writing about how to get this right could fill lots of articles and many books.

However, leaders and managers are key here. Simple things like modelling the right language can make a considerable difference, for example “What would happen if…..?” or “I wonder if we could change….?”

Questions like this encourage us to pause for thought and reflect.

As settings open to even more children a simple option might be to have a weekly ‘reflective question’ which is shared with everyone. These questions might be good options:

- How are children engaging with the new layout or routine?

- How are children displaying their levels of wellbeing?

- Which activities are the most popular and why?

- Have there been any surprises this week?

- Which activities might we introduce?

- What are we most concerned about?

Inviting everyone to contribute is important. It ensures that all feel their views are valued and that their reflections can help to improve the experience and learning of children.

Dr Helen Edwards is co-founder of Tapestry, an online learning journal for early years and schools which encourages reflective practice. For more information visit tapestry.info .

You may also be interested in...

- Great ways to support communication, language and literacy

- How to provide outstanding learning in the outdoors

- Award winners announced

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

I agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy & Cookies Policy.

Enhance your children’s learning environment with unique products from Profile Education

Review – Sleep Stories

Enrol now for courses with Modern Montessori International

Wanna See a Llama? – picture book

View all Top Products

What Will You Be, Grandma?

Lively elizabeth.

Brave As Can Be

Recommended for you....

Teach Early Years Awards 2021 finalists announced

Editors picks

Observations in Early Years – Supporting staff to make them meaningful

EYFS writing – Help children develop physical skills

Planning In-depth Interactions With Children in the Early Years

- NAEYC Login

- Member Profile

- Hello Community

- Accreditation Portal

- Online Learning

- Online Store

Popular Searches: DAP ; Coping with COVID-19 ; E-books ; Anti-Bias Education ; Online Store

Learning Stories: Observation, Reflection, and Narrative in Early Childhood Education

You are here

As an early childhood educator committed to equity of voice, I believe that educational activities with preschool children should be based on daily observations of children at play both in the classroom and outdoors. These observations should include teachers’ reflections and, as much as possible, families’ opinions and perspectives on their children’s learning, curiosity, talents, agency, hopes, and dreams. As a preschool teacher in a multi-language setting, I am required to conduct classroom observations to assess children’s learning. This has led me to the following questions:

- How can early childhood educators support and make visible children’s emergent cultural and linguistic identities?

- How can teachers embed story and narrative to document children’s growth and strengthen families’ participation in their children’s education?

In this article, I describe Learning Stories, a narrative-based formative assessment created by New Zealand early childhood education leaders. Learning Stories provide a way to document children’s strengths and improve instruction based on the interests, talents, and expertise of children and their families.

Learning Stories as Assessment

In New Zealand, educators use the Learning Stories approach to assess children’s progress. This narrative tool is a record of a child’s life in the classroom and school community based on teachers’ observations of the child at play and work. It tells a story written to the child that is meant to be shared with the family. Learning Stories serve as a meaningful tool to assess children’s strengths and help educators reflect on their roles in the complex processes of teaching and learning. As formative assessments, they offer the possibility of reimagining all children as competent, inquisitive learners and all educators as critical thinkers and creative writers, genuinely invested in their children’s work.

How Learning Stories Are Distinct

Learning Stories break away from the more traditional methods of teaching, learning, and assessment that often view children and families from a deficit perspective, highlighting what they cannot do. By contrast, Learning Stories offer an opportunity to reimagine children as curious, knowledgeable, playful learners and teachers as critical thinkers, creative writers, and advocates of play. Learning Stories are based on individual or family narratives, and they recognize the value of Indigenous knowledge. For native, Indigenous, and marginalized communities, the telling of stories or historical memoirs may be conceived as something deeply personal and even part of a “sacred whole,” as Maenette K.P. Benham writes. When we engage in writing and reading classroom stories—knowing how they are told, to whom, and why—we uncover who we are as communities and, perhaps, develop a deeper appreciation and understanding of other people’s stories.

Educators can use Learning Stories to identify developmental milestones with links to specific assessment measures; however, the purpose is not to test a hypothesis or to evaluate. At the root of any Learning Story is a genuine interest in understanding children’s lived experiences and the meaning teachers, families, and children themselves make of those experiences to augment their learning. As Laura Hope Southcott reminds us, “Teachers choose a significant classroom moment to enlarge in a Learning Story in order to explore children’s thinking more closely.”

Although no two Learning Stories will be alike, a few core principles underlie them all. The foundational components include the following:

- an observation with accompanying photographs or short videos

- an analysis of the observation

- a plan to extend a child’s learning

- the family’s perspective on their child’s learning experience

- links to specific evaluation tools

Suggested Format of a Learning Story

The following format is a helpful guide for observing, documenting, and understanding children’s learning processes at any given moment during the school day. It also may help teachers organize fleeting ideas into a coherent narrative to make sense of classroom observations or specific children’s experiences.

- Title: Any great story begins with a good title that captures the essence of the tale being told. Margie Carter suggests that the act of giving a title to a story be saved for the end, after the teacher has written, reflected on, and analyzed the significance of what has been observed, photographed, and/or video recorded.

- Observation: The teacher begins the story with their own interest in what the child has taken the initiative to do, describing what the child does and says. When teachers talk and write the story in the first person, they give a “voice” to the storyteller or narrator within. In their multiple roles as observers, documenters, and writers, teachers bring a personal perspective that is essential to the story. They write directly to the child, describing the scene in detail and narrating what they noticed, observed, or heard. Accompanying photographs, screenshots, or still frames of a video clip of the child in action serve as evidence of the child’s resourcefulness, skills, dispositions, and talents.

- What Does It Mean? (or What Learning Do I See Happening?): These are questions teachers can use to reflect, interpret, and write about the significance of what they observed. This meaning-making is best done in dialogue with other teachers. Multiple perspectives can certainly be included here; indeed, objectivity is more likely to be reached when the Learning Story includes a variety of voices or perspectives. Ask your coteachers or colleagues to collaborate to offer their pedagogical, professional, and personal opinions to the interpretation of the events.

- Opportunities and Possibilities (or How Can We Support You in Your Learning?): In this section, teachers describe what they can tentatively do in the immediate or distant future to scaffold and extend the child’s learning. How can they cocreate with children learning activities that stem from individual or collective interests? This section might also reveal teachers’ active processes in planning meaningful classroom activities while respecting children’s sense of agency.

- Questions to the Family: This is an invitation for a child’s family to offer their opinions on how they perceive their child as a competent learner. It is not uncommon for a child’s family to respond with messages addressed to the teacher. However, when teachers kindly request family members to reply directly to their child, they write beautiful messages to their children. Sometimes, the family might suggest ideas and activities to support their child’s learning both at home and school. They might even provide materials to enhance and extend the learning experience for all the children in the class.

- Observed Milestones or Learning Dispositions: Here, teachers can link the content of a child’s Learning Story to specific evaluative measures required by a program, school district, or state. They also can focus on the learning dispositions reflected in the story: a child’s curiosity, persistence, creativity, and empathy. The learning dispositions highlighted in a Learning Story reflect the emerging values of children and the values and beliefs of teachers, families, schools, and even the larger community.

Learning Stories in Practice

My preschool is part of the San Francisco Unified School District’s Early Education Department. Our school reflects the ethnic, economic, cultural, and linguistic mosaic of the school’s immediate neighborhood, which consists primarily of first- and second-generation immigrant families from Mexico, Central America, and Asia. When children enter our program, only about 10 percent feel comfortable speaking English. The others prefer to speak their home languages, meaning Spanish, Cantonese, and Mandarin are the most common languages in our school.

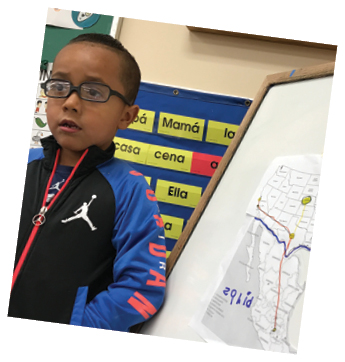

One child, Zahid, revealed his story-telling skills by sharing the story of his father’s attempt to cross the border between Mexico and the United States. (See “Waiting for Dad on This Side of the Border” and “Under the Same Sun” below.) The resulting Learning Stories provided a structure for documenting Zahid’s developmental progression over time and for collecting data on his language use, funds of knowledge, evolving creative talents, and curiosity for what takes place in his world—all of this in his attempt to make sense of events impacting his family and his community.

The Learning Stories framework honors multiple perspectives to create a more complete image of each learner. These include the voice of the teacher as narrator and documenter; the voice, actions, and behaviors of children as active participants in the learning process; and the voices of families who offer—either orally or in writing—their perspectives as the most important teachers in their children’s lives.

Waiting for Dad on This Side of the Border May 2017

What happened? What’s the story? Zahid, I admire your initiative to tell us the tale of the travels your dad has undertaken to reunite with you and your family in California. On a map you showed us Mexico City where you say your dad started his journey to the North. You spoke about the border (la frontera), and you asked us to help you find Nebraska and Texas on our map because that’s where you say your dad was detained. We asked you, “What is the border?” and you answered: “It is a place where they arrest you because you are an immigrant. My dad was detained because he wanted to go to California to be with me.”

What is the significance of this story? Zahid, through this story where you narrate the failed attempt of your dad to get reunited with you and your family, you reveal an understanding that goes well beyond your 5.4 years. In the beginning you referred to the map as a planet, but perhaps that’s how you understand your world: a planet with lines that divide cities, states, and countries. A particular area that called your attention was the line between Mexico and the United States, which you retraced in blue ink to highlight the place where you say your dad crossed the border. It is indeed admirable to see you standing self-assured in front of the class ready to explain to your classmates your feelings and ideas so eloquently.

What’s the family’s perspective? Zahid is not very fond of writing, but he talks a lot and also understands quite a lot. He doesn’t like drawing but maybe with your support here at school he could find enjoyment in drawing or painting. —Mom

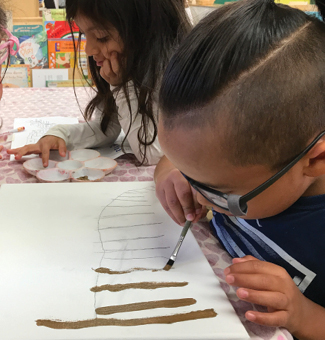

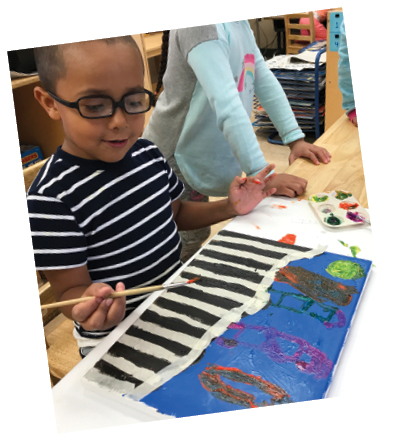

Under the Same Sun May 2017

What is the significance of this story? Zahid, I’m very pleased to see your determination to make a graphic representation of the word frontera. After so many sessions singing the initial sounds corresponding to each letter of the alphabet in Spanish, I thought you would be inclined to sound out the word frontera phoneme by phoneme and spell it out to write it on paper, but that was not the case. Instead, you decided to undertake something more complex, and you chose a paint brush and acrylic colors to represent (write) la frontera the way you perceive it based on the experiences you have lived with your family and, especially, with your dad.

What possibilities emerge? Zahid, you could perhaps share with your classmates and your family your creative process. Throughout the entire process of sketching and painting you demonstrated remarkable patience since you had to wait at least 24 hours for the first layer of paint to dry before applying the next one. You chose the color brown to paint the wall that divides Mexico and the United States because that’s what you saw in the photos that popped out in the computer screen when we looked for images of the word frontera. You insisted on painting a yellow sun on this side of the wall because according to you, that’s what your dad would see on his arrival to California, along with colorful, very tall buildings with multiple windows. I hope one day you and your dad can play together under the same sun.

This article is an adaptation of “Learning Stories: Observation, Reflection, and Narrative in Early Childhood Education,” by Isauro M. Escamilla, published in the Summer 2021 issue of Young Children .

Also, check out the latest NAEYC book, Learning Stories and Teacher Inquiry Groups: Reimagining Teaching and Assessment in Early Childhood Education . You’ll learn more about how to integrate the Learning Stories approach and teacher inquiry groups into your setting.

Photographs: Header Image © Getty Images; Photos courtesy of the author Copyright © 2022 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See permissions and reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions .

Isauro Escamilla, EdD, is assistant professor in the Elementary Education Department of the Graduate College of Education at San Francisco State University, where he teaches Language Arts in K–5 Settings and Spanish Heritage Language and Pedagogy for Bilingual Teachers, among other courses.

Vol. 16, No. 1

Print this article

- Mission & Equity Vision

- Board of Advisors

- Why SEL Matters

- SEL & ECSEL

- Begin to ECSEL Comprehensive Training

- ECSELent Adventures Curriculum

- Educator Well-Being Short Course

- Reflective Practice Short Course

- Curriculum Library

- Tools & Books

- In The News

- Media & Speaking Inquiries

The Power of Reflective Practice in Early Childhood Education - Part I: Helping Caregivers Tap Into Their Best Selves

Reflective Practice ensures that all members working in the educational community get the opportunity to communicate their self-reflections about how their work, their role, their actions, and their words impact others—and how they, in turn, are impacted by their work. ~ Dr. Donna Housman, Founder & CEO of Housman Institute

In an article for Edutopia, clinical social worker Megan Tavares writes, “ Self-reflection… can help us figure out if what we’re doing is working. When supporting a learner with self-regulation, one reason that self-reflection is important is the ability to notice our own mood and presentation. Otherwise, we may unknowingly create problems by co-escalating instead of co-regulating . ” 1

For all educators and caregivers, there is great value in being able to understand and manage our own feelings through self-reflection. In doing so, we can help children to do the same.

As we very well know, children are emotional detectives. They pick up on everything , including the verbal and non-verbal responses and reactions of the important adults in their world. If we as these important adults do not have an awareness of our own emotions, the skills to understand and manage them, or a means to actively practice self-reflection, we may unknowingly contribute to a problem rather than work towards a solution.

So, how do we collectively tap into our best selves so that we can be our best, not only for the children that we care for and teach but also for ourselves?

The answer is Reflective Practice . In this 4-part series, we will explore the important impact that self-reflection through Reflective Practice can have on all members of a school community, and hear from teachers, mentors, and parents about the difference that Reflective Practice has made within themselves and their role as key socializers for children. But first, let’s explore the details of this invaluable process together.

What is Reflective Practice?

Reflective Practice is Housman Institute’s adaptation of Reflective Supervision. It is a process that focuses on self-reflection as a means of becoming more emotionally aware, thinking critically, problem-solving, identifying one’s own areas of growth, and meeting those goals in our everyday work. It creates an environment that promotes self-reflection, empathy, understanding, support, and professional and personal growth and development. Reflective Supervision traditionally occurs in structured sessions between a trusted mentor, coach, or supervisor and a mentee, but with Reflective Practice, self-reflection, critical thinking, and problem-solving can also take place less formally between all members of your education community— between educators and children, educators and their co-workers, or educators and families. Reflective Practice allows individuals to become more aware of their emotional triggers and learn how to manage and navigate them with guidance from a mentor. It lays the groundwork for ongoing professional development through consistent self-reflection, community support, and emotional awareness.

Within Reflective Practice relationships, trust and consistency are key. Opening up and revealing one’s challenges and emotions can make us feel vulnerable. In fact, Reflective Practice sessions can be uncomfortable, at first. This makes the mentor’s job all the more valuable and important. Mentors need to be active and thoughtful listeners who are understanding, accepting, and non-judgmental. Being collaborative, open-minded, solution-driven, and supportive sets the stage for a successful reflective relationship between mentors and mentees.

You may now be wondering, “Okay, so what exactly is included in Reflective Practice? How do I do this? How can I incorporate Reflective Practice into my routine? What difference will Reflective Practice make for me?” These are all valid questions! Let’s walk through them together.

Reflective Practice sessions have six key steps that follow the Gibbs Reflective Cycle. During these sessions, mentors support their mentees in self-reflection by asking open-ended questions to prompt critical thinking, and actively listening to mentees’ responses and contributions.

Step 1: Description

The mentor prompts the mentee to describe a challenging experience or interaction by asking, “What happened?” and participating in active listening. This gives the mentee a safe space to reflect on the experience and describe the details of what happened in their own words.

Step 2: Feelings

The mentor prompts the mentee to connect the challenging experience to their feelings by asking, “What did that make you feel?” and continuing to actively listen. Connecting emotions to a cause not only helps mentees better understand their feelings but can also help bring to light any emotional triggers, which mentors can then support mentees in navigating and managing.

Step 3: Evaluation

The mentor guides the mentee to evaluate how the experience went by asking, “What went well? What didn’t? How did you contribute?” This is an important step, as it takes any judgment away from what happened, and allows mentees to look at their experience through a critical and empathetic lens.

Step 4: Analysis

The mentor supports the mentee in understanding the meaning of the experience by asking, “Why do you think things went well? Why didn’t other things go as planned?” and actively listening before providing their own insight. At this point in the session, mentees are able to reflect on what they have learned, what else could have worked better, and move closer to making a plan.

Step 5: Conclusion

The mentor asks the mentee, “What could you have done differently?” and supports them in concluding their self-reflection and learning. Once again, asking open-ended questions allows most of the critical thinking and planning to come from the mentee’s own ideas, making it more likely that they will follow through with any changes.

Step 6: Action Plan

The mentor prompts the mentee to think about what they would do differently by asking, “What will you do differently if a similar situation arises? What support do you need to accomplish this?” This final step is crucial. Just because a plan is made does not mean the session is over. Mentees need to be assured that there will be follow-through and accountability, as well as support for carrying out their plan of action.

Following each of the steps of Reflective Practice can help us to become more self-reflective and in turn more emotionally aware. Mentors can help prompt this reflection, as well as critical thinking and problem-solving, so we can be more proactive when it comes to our stressors and events that can cause them. The steps of Reflective Practice can also be applied during our daily routines with the children in our care, co-workers, families, and the entire community.

Why Reflective Practice Matters

When we are able to take a step back and realize, “This isn’t working,” we end up giving ourselves space to consider what could work better. Whether it’s how we interact with children, support their many emotions and behaviors, or develop engaging curricula or activities, Reflective Practice allows us to look inward so we can show up and be our best selves for children. We can reflect on their needs and adjust our tone of voice, facial expressions, body language, support strategies, and problem-solving, all with their needs in mind to make learning fun. Reflective Practice allows educators and caregivers to use empathy and practice perspective-taking with others— reflecting not only on how we may feel, but how others might feel as well, and actively finding ways to improve communication. We can tune into the emotional responses of others in order to act with compassion and empathy during challenging conversations, creating respectful partnerships rather than confrontations. Reflective Practice also allows mentors and supervisors to welcome others into a safe environment to identify their areas of growth, goals, and how to accomplish them.

The act of self-reflection through Reflective Practice allows all caregivers to tap into their best selves both personally and professionally, which can help to strengthen the entire school community. We have seen firsthand how improving self-reflection has benefitted us as teachers in the classroom with students, as human beings at home with family and friends, and as mentors who continue to follow the steps of Reflective Practice to be our best selves and support mentees to do the same.

References:

- “A Teacher’s Use of Self in the Preschool Classroom.” n.d. Edutopia. Accessed January 4, 2023. https://www.edutopia.org/article/teachers-use-self-preschool-classroom.

Read the entire Reflective Practice Series

- Helping Caregivers Tap Into Their Best Selves

- An Educator's Journey

- The Importance of Mentor Relationships

- Helping Parents Tap into Their Best Selves

- Everyday Tips for Tapping Into Your Best Self

You May Also Like

These Posts on Early Childhood Education

The Power of Reflective Practice in Early Childhood Education - Part III: The Importance of Mentor Relationships

Instill Wonder in Young Children With Earth Day Activities

SEL as a Pathway for Mitigating Effects of Learning Loss

Subscribe by email, no comments yet.

Let us know what you think

Housman Institute, LLC

831 Beacon Street, Suite 407 Newton, MA 02459 [email protected] (508)379-3012

- Our Research

- Why It Matters

Our Products

- begin to ECSEL®

- ECSELent Adventures

- Educators' Well-Being

- Leaders' Well-Being

- ECSEL Curriculum Library

- Privacy Policy

- Terms Of Use

- Support Request

Join our Mailing List!

Subscribe to receive our newsletter, latest blogs, and SEL resources.

We respect and value your privacy .

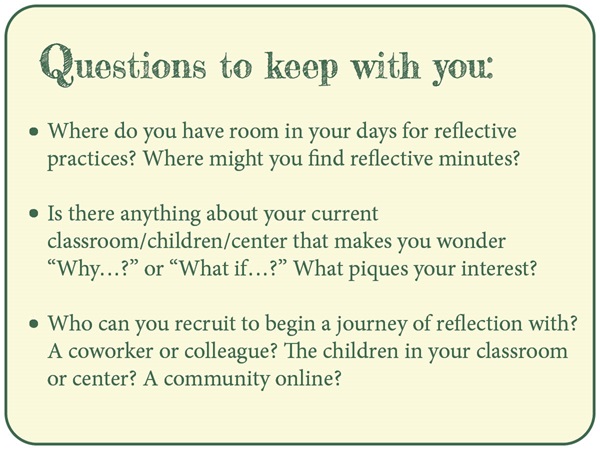

Carving Out Time for Wonder:

Reflective practices in early childhood pedagogy.

The topic of reflection in early childhood education is often met with a mixture of admiration and frustration. Yes, we all know that reflection is a critical piece of an early educator’s toolbox—a component of practice that deepens our appreciation of, and understanding of, young children. We admire those who do this. However, finding the right time for it—amid busy schedules, packed days, and mounting obligations, (not to mention personal lives that are rich and full!), can be difficult if not frustrating. What, then, can we do to encourage our colleagues and ourselves to find and create time for this reflection that we know is so valuable in our day-to-day practice?

Rooted in Wonder

Reflective practices are rooted in wonder. Wonder, here, refers to a disposition of curiosity that is taken toward an event or phenomenon that we observe. This wonder, in turn, serves as the central motivation behind one’s reflection, leading eventually to a rabbit hole down which an educator feels motivated to travel. This motivation, especially when it is intrinsic, is an important catalyst for reflection. Indeed, there is a unique feeling as one travels down this path of wonder—a so-called rabbit hole—propelled by genuine curiosity. Suddenly, there is no longer an option to stop learning; the sensation of intrigue and joy of making new connections is a self-propelling engine.

Asking “Why?” and “What If?”

A wondering disposition, in turn, invites educators into questions that begin in “Why…?” and “What if…?”. Asking “why” and “what if” questions can deepen an educators understanding of children’s interactions, and also deepen the educators understanding of their reaction and role in the learning. Children’s exploration of themes such as superheroes, animals, or royalty, or their exploration of a certain artistic material, are often common entry points for wonder. Imagine, for example, that the children in your care are endlessly intrigued by a game of kittens, which they enact through a series of rough tackles, dogpiles, and endless laughter.

A child-centered “Why?” might ask : Why are the children so enthralled by this game? Why do the children insist on rough play as part of this game?

An educator-centered “Why?” might wonder : Why am I as an educator so unsettled by the children’s rough and tumble gross motor play?

A child-centered “What if?” might ask : What if the children had other ways to explore the juxtaposition of roughness and tenderness? What if we discussed the purpose and role of rough play in baby animals? Where might this lead and what might it reveal?

An educator-centered “What if?” might wonder: What if I change the language I use to describe play to myself, my colleagues, and in my documentation? What if I made efforts to find a more precise, respectful lexicon to describe the unfolding work of the children?

Making Time: In Your Practice

Just as no one child’s work will be exactly the same in process or in content as the work of another, so too does each reflective practice look different. That is the beauty of authentic reflective practice. However, there are a few principles that might be handy for those seeking to begin, sustain, or re-imagine a reflective practice.

You are already reflecting! You are already reflecting as part of your ongoing work as an educator. As early educators, our entire day is anchored in children: we ask questions about children, we gather data and information about children, about what they know, what they are learning, and the ways that they are experiencing the world.

Regardless of the particular features of your environment—whether, for example, it uses a progressive emergent-curriculum lens, or is a corporate center that must report on particular metrics on a fixed timeframe—as educators we are in the business of reflecting on the lives of children. Internalizing this truth can be helpful as we consider the following points.

- Reframing and rephrasing daily practices and inquiries. The language we use has an important impact on the way we view the world—it is why we are so careful to use precise language with young children. Observing a child spending time writing letters and letter-like forms on a sheet of paper we might move from asking: “What does this child know about letters?” to something like: “I wonder what about letters is intriguing to this child? Their forms? Their communicative potential?”

- Incorporating Others into the Reflective Process. Another efficient way to reflect is to embed it into classroom rituals that already exist, folding others (e.g. colleagues and children) into the process. A simple conversation over snack time counts as reflection—as does wondering, asking, speaking, and thinking with children. This might occur during a regular meeting time, as you walk from one room to another, or over a weekend coffee.

Making Time: In Your Environment and Context

In their book, From Teaching to Thinking , Ann Pelo and Margie Carter note that reflective practices can only exist when they are promoted and provided for in the “visions and values” that “anchor organizational systems.” (2018, p. 103). Succinctly, a critical component of reflective practice and teacher research is making time not only in classroom-based practice, but within the institutional structures within which educators exist.

Making time isn’t necessarily easy, but it is worthwhile. To begin, one might wonder: What works for me? When am I most excited to think about the classroom? Is it in the middle of the day, as the events unfold? During a scheduled planning time? The truth is that there is no way around it, reflective practice takes time—however, it needn’t be laborious.

Perhaps this time begins with a reflective minute appended to a break (to use the restroom, grab coffee, eat a snack, etc.) A reflective minute inviting yourself to wonder is the perfect spot to begin—inserted here and there over the course of days and weeks, these minutes add up. As you continue to work to find these moments, they will become easier and more efficient.

The Fruits of Reflection: Cultivating Intentionality

The fruits of reflection are many—including, but not limited to, increased intentionality, more entrenched habits of inquiry, and perspective shifts that have the potential to impact the ways we view ourselves, our colleagues, and the children with whom we work.

- Perspective Shifts . Reflecting frequently and in the company of others invites us to look outside of ourselves and our own experiences for answers. This occurs through discussions and dialogue with ourselves, others, ideas, etc. When we reflect, even on our own previous conceptions, we learn to let go of our established ideas and frameworks. This propels us onward in the search of more answers that will lead us along the paths of wonder and awe.

The most important thing we can do as educators is to maintain a reflective disputation toward our practice. There is always room to begin anew, deepen your existing practice, and to discern what works best for your particular interests, needs, and context. Reflection and its fruits are, ultimately, a testament to an image of children as capable human beings who lead rich lives, hold complex ideas, and experience the world deeply.

Ron is an early childhood educator with a passion for child-centered and constructivist methodologies. He encourages his children to learn through art, nature, and play and enjoys exploring the ways that these connect to deep processes of creative, personal, and academic inquiry. Ron earned a Master’s in Early Childhood Education from the Erikson Institute in Child Development and a Bachelor’s Degree in Psychology from Stanford University. Ron has been working with children and families for nearly a decade in both research and applied contexts and is currently a teacher at NOLA Nature School in New Orleans, Louisiana. Ron also serves as a consulting editor for Young Children , and is the author and illustrator of a children’s book due out in 2023 with Penguin/Paulsen. His writing has appeared in Young Children , Teaching Young Children , and Exchange.

Connect with Ron at https://www.childology.co

Let's stay in touch

Request a Free Catalog:

Sign up for our weekly blog

Reflection & Reflective Practice in Young Children

It has been thought for a long time that young children are not capable of self reflection yet how many times do we see parents or educators saying “You think about what you have done.” Are young children even capable of reflecting on situations and circumstances and are they cognitively able to incite change through those self reflections?

Reflection is a vital part of learning. Think about your journey when learning a new skill or concept. It takes observation, practice and reflection to move from a point of no skill to skill. We know children can observe and they use that in learning all the time. They imitate adults and their peers and then manipulate those things they have learned through play, in order to learn more.

For example, when learning to speak, a child observes and copies what they see and hear. They practice the words and sounds over and over until they have mastered them. At first it is just straight mimicking, but as they grow slightly older (around 3 years), they start to play with those words, forming nonsense words, rhyming words and playing with the language in all sorts of ways which teaches new skills. But do they reflect on what they are learning? Is reflection part of their learning process?

Historically, it has always been believed that young children (under 11 years) do not have the capacity for self-reflection ( Flavell, 1977 ). Later research, as late as 2016 backed up this same view ( Robson, 2016 ). Although Robson agrees that observation and reflection go hand in hand, the thought was still that children under the age of 11 years did not have the capacity for self reflection.

“Movement allows children to connect concepts to action and to learn through trial and error. Young children explore their world through movement, using all the senses so it is only logical to use what they already know to promote further skills such as reflective practice” DIANA F CAMERON

The research of Mario Biggeri (2007) showed that “Children from the age of 11 have been shown to have conceptualising abilities that enable them to reflect on their experiences”. But it wasn’t until research in 2010 when the concept that children’s opinions and perspectives were important and they were able to reflect on experience and have a subtle understanding of them that more research opened the possibility that self-reflection was possible in younger children ( Buhler-Neiderberger, 2010 ).

Robson agreed that children who are given the opportunity to self reflect become better at it over time. There is also something else that is developed simultaneously when having the opportunity for self-reflection and that is the ability to develop symbolic thought and to be able to represent ideas.

First Things First

In order for a child to be able to reflect on an event, they must first be self-aware. There are many ways to help a child with self awareness, and although they are still learning, we know that young children (younger than 11 years) are self aware. So doesn’t it stand to reason that we could use the ability of self awareness to engage and develop reflection abilities?

So What is Reflection?

First, we need to qualify what we mean by reflection. Similar to critical thinking, it can’t be learned or practiced in isolation but needs to be in taught in context. It needs to be conscious and it needs to happen in relation to an experience.

By reflecting on experiences, children are able to implement change by looking at things differently and then changing how they react to a similar experience. Developmental research suggests that “there are age related increases in the highest degree of self-reflection” ( Zelazo, 2004 ). There are factors, however that directly influence a child’s ability for self-reflection and those are their developmental age, and their language ability ( Zelazo, 2004 ).

Why is Self-Reflection Important?

When play is accompaniment by self reflection, it leads to deeper learning and understanding. Improving a child’s ability to self-reflect directly impacts on:

- Self regulation – The ability to respond to circumstances and demands with a range of emotions that are in keeping with appropriate social expectations and flexible enough to allow spontaneous reactions as needed. In other words, knowing cognitively which coping strategy to implement so their reaction is in keeping with the circumstance.

- Mindfulness – being present in activities and aware of themselves at every moment.

- Metacognition – thinking about thinking

- Learning – the ability to reflect and instigate change is an essential part of learning

How Do We Assist Self-Reflection in Young Children?

As mentioned before, for young children to be able to self-reflect, they first need to be self-aware. Movement is one of the best ways I know of implementing this with young children. As a Kindermusik educator, I know the importance of movement and musical experiences for young children and the many benefits of moving. We do exercises with children where they learn to isolate individual body parts and coordinate others, building on self-awareness with every move.

We are running the risk with our increasingly passive learning environments in preschools, of inhibiting the opportunities for children to learn self-awareness and reflection. It is important for them to be allowed to move freely, choosing their own activities and participating in self-directed learning. This is how we lead children through self-awareness to the skill of reflection.

Movement allows children to connect concepts to action and to learn through trial and error. Young children explore their world through movement, using all the senses so it is only logical to use what they already know to promote further skills such as reflective practice.

Memory and movement are linked. Memory is also a part of the reflective process; without memory of the situation, a child can’t reflect on it. Children need opportunities to move, even school aged children . Their body is a tool for learning and must be utilized as much as possible. The more senses that are engaged, the deeper the learning.

What Types of Movement Should I Be Using?

Different types of movement are a great way to increase self-awareness and can lead to opportunities to teach self-reflection. You could try the following:

- Free movement to music

- Movement isolating 1 body part at a time. “Jazz hands” or moving just a shoulder, or do the hokey pokey

- Movement using a variety of props – balls, scarves, streamers, stuffed animals or keeping a balloon in the air

- Mirror Dancing. Dance like I am dancing, now I will dance like you are dancing

- Cross Lateral Movements – where the opposite arm and leg are moving at the same time or anything where the arms cross the body

- Use extremes of movement – very high, to very low. All the way from one side to the other side etc

- Move while balancing on one leg

- Only use 1 side of your body at the one time when you move

- Stop and go movement – for children 3+ years, when you stop get them to make a shape with their bodies (like a statue) which adds another layer of complexity to the activity

- Different types of moving – upside down, crawling, hopping, dancing, jumping – using the body in various ways

So What is the Research Telling Us?

Putting it all together, it is possible for young children to reflect and in fact, it is important to teach them those skills by allowing them the opportunity to practice. This is what we can learn from the latest research about young children:

- Self awareness is best practiced through movement.

- Children must first be self aware before they can develop self reflection.

- Self awareness leads to better self regulation.

- Self regulation happens in the body through movement. Intentional movement, such as yoga or moving to music has profound effects on a child’s ability to focus and calm themselves.

- Reflection is a vital part of learning.

- Memory and movement are linked. Memory is needed to develop reflective practices.

- Young children are capable of self reflection and instigating change but it is directly dependent on their developmental age and their language abilities.

- Self reflection develops symbolic thought and the ability to represent ideas through symbols.

Diana Cameron

Diana has over 32 years in the early childhood industry and has been a guest lecturer and workshop facilitator both nationally and internationally for the past 20 years. She has a passion for inspiring educators to use creativity and imagination in their teaching.

Recent Posts

11 Activities to Improve Sitting Behavior & Tolerance

Sitting tolerance is a thing. Some children have it, others struggle. So, what can you do to help develop sitting tolerance in the children you care for? Several activities improve...

What is the Job Description of an Early Childhood Professional?

There are many different positions for Early Childhood Professionals and while there are similarities, some have very different expectations. If you are planning on going into this field, you need...

The Empowered Educator

Inspiring ideas, training and resources for early learning.

Simple Critical Reflection for Educators

by The Empowered Educator 11 Comments

When you mention critical reflection to early childhood educators you are likely to be met with a deer in the headlights stare and someone immediately asking if it is too early for happy hour at the bar! A slight exaggeration obviously but it is something that many educators tell me they find difficult so don't feel like you are the only one thinking of an exit strategy when someone asks to see your critical reflections!

I've shared some tips before on weekly reflections along with the reflection we do when we observe children, analyse their learning and identify how to further extend that learning if we decide it is necessary.

But the new buzzword in early childhood seems to suddenly be critical reflection and this is where educators are getting confused and not sure of the difference between everyday reflective practice and the now common term - critical reflection. So I thought it was a good time to break it down into some simple steps and I'm also giving you an action plan you can download to make sure you can get started!

Critical reflection is an important part of many professions and workers and therefore not just a requirement of early childhood educators but in this blog I'm going to be focusing on how the concept relates to us as educators and how it can improve our work and the outcomes for children in our care. You might still want a wine or two to work your way through this one though 😉

You can also grab my free critical reflection guide below if you'd like a little extra help...

Let's get started breaking it down ….

What Critical Reflection?

Critical reflection means regularly identifying and exploring our own thoughts, feelings, and experiences and then making a decision about how they fit in with the ideas, concepts, and theories that you are aware of, learning more about or others have been discussing and sharing.

The idea is that you are not only exploring your own thoughts, events and experiences that have occurred, but you are also examining them from different perspectives and considering whether this might in fact change your approach or own perspective. It is a way to consistently evaluate your actions and approaches to early learning and an early childhood educator role. Critical reflection is a common practice in many professions to help workers improve, change or reexamine current practice, perspectives, thinking and skills. It is something I have had to do in my work as an educator over the years but also in my family services and project manager roles. The basic premise is the same so it's not just something that the early years learning framework made up just to give educators like you more paperwork to do (there were other ways they achieved this 😉 ).

Reflection shouldn’t (or doesn't need to!) be about always looking for something you or others might have done wrong though– think about it as being prepared to identify your current values and biases and at least consider and explore a colleagues view that might differ to your own. Discuss with others about how their view influences their own practice in this area and perhaps how you could try a different way of doing something to see what happens. When you are looking more closely at the viewpoints of others your aim is to engage in constructive debate and discussion that allows everyone to see some different perspectives – not to try and change someone’s mind by belittling their views, actions or emotions or put your own point across aggressively without being open to the possibility of some change.

Why is Critical Reflection important?

To put it simply – because it helps you as a professional early years educator to make changes and improvements to your practice, knowledge, interactions, actions and learning environments.

Critical reflection can highlight for you areas you might like to learn more about, understand better or find different ways to approach that practice. You might use some of the information to add goals and changes that you need to make to your quality improvement plan.

You can also use critical reflection regularly to analyse and identify children’s learning and development (as individuals and in groups)to better inform your ongoing planning.

We must always try and keep in mind that our reflections and discussions should ultimately lead to the best possible outcomes for the children in our care. Don't get hung up on just what it means for you – try and keep an eye on the bigger picture and why you are reflecting in the first place!

How is it different to my general daily or weekly reflections?

I like to think of critical reflection as going one or two steps further on from your regular weekly reflective practice that you do when you look back on how last week's program went or make quick notes about an activity or child.

The aim of critical reflection is actually to use it as an ongoing tool to build on your current practice and ask important questions not only of those actions, environment and activities – but also of why you choose to do those things that way that you do, how theories and perspectives might have informed your approach, how your actions might have impacted on others and what others viewpoints on this approach or action might be.

How often do Educators have to ‘critically reflect?

As critical reflection is an ongoing process there are no set rules for how often you should set aside time to document your reflections.

To get started taking regular action though you might like to consider 1 or 2 of the questions from my list further down below and then add your answers and thoughts to the end of each week’s planning. I’ve made this easier for my Empowered Educator Academy Ed's by adding a critical reflection prompt section to complete in the done for you planners and program templates.

It can take a little time to learn the skill of critical reflection so by adding a few notes at the end of each weekly program it should help you get in the habit of exploring and learning more about how to use this practice effectively as everyday practice without it becoming time consuming or overwhelming. Some of the questions also help you to involve other people in your reflections and therefore expand and challenge your own thinking.

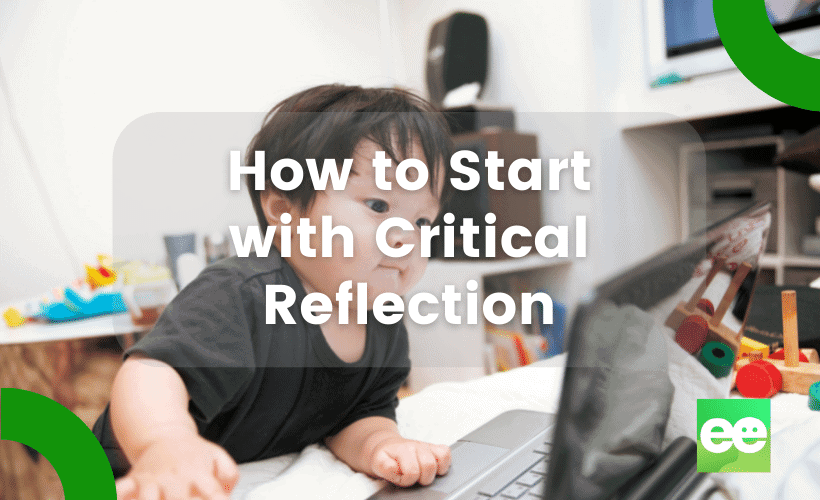

How can I get started with ongoing critical reflection?

If you are still a little confused about the process of critical reflection or struggling to begin, try setting aside some time to think about how you might answer 1 or 2 of the following questions at the end of a week before you begin next week's planning. Think about how your answers to these questions and the discussions surrounding those answers might regularly encourage further learning, help you to gain clarity and inform your future decisions about the children’s learning.

When you have identified your answers to a couple of the questions below you could then use them to begin drawing up an action plan you can revisit and update regularly . This creates a simple yet visible system of ongoing critical reflection without it taking a lot of your time each week!

Not sure how to get started on an action plan or even what to reflect on? I've got a FREE step by step guide for you and you can grab one below…

Critical reflection certainly doesn't need to be complicated or become something that takes a lot of time but isn't helpful to you or the children. We just need to keep it simple but do a little bit often! No matter what you might have read online in the groups and forums….it's not easy for everyone to begin doing straight away and learning to initiate and accept critical reflection is a skill that needs to be continually practiced – just like assertive communication skills .

It's not something you are meant to just ‘get' overnight or find easy straight away -so instead of pressuring yourself to reflect on absolutely everything to make sure you are doing it ‘correctly', break up ongoing critical reflection into smaller more manageable steps and begin with one question at the end of your week, add it to your action plan and then take it from there.

You might decide to put more effort into exploring just one area you identify from your answers for now and then ask some more specific questions regarding this practice as the year progresses.

Questions to prompt deeper critical reflection.

- How did my own experiences and knowledge influence my understanding and actions of a particular activity or interaction this week?

- How did I take into account the needs, perspectives and opinions of parents and their children in this situation?

- Did my personal values and possible biases enter impact on my experiences this week?

- How do my fellow educators, leader or view this situation or action?

- What do I need to find out more about?

- What other theories might provide me with a different viewpoint on this subject?

- In what way are my choices determined by the expectation of my early learning service or leader?

- What does this action/environment/observation tell me about?

- How can I acknowledge, respect and value children’s diverse identities?

- How could my team members/coordinator/leader/friend help me in this area?

- Were there broader social and/political or emotional issues that influenced my actions?

- Did my usual assumptions mislead my practice somehow? What assumptions can I challenge next time?

- What knowledge did I use to reflect upon observations this week?

- Why do I think that?

- What did I learn about this?

- How would I do it differently or better next time?

- How might the outcome of that activity/experience been different if I ……..

- What do you think? Why is that? How does it work for you? Why do you think your approach works more effectively than mine?

- What can I do next or differently to further extend the children’s (or my own!) learning?

These questions from the Australian Early Years Learning Framework are also very helpful to begin and guide reflection (although obviously more in depth):

- Who is disadvantaged when I work in this way? Who is advantaged?

- What are my understandings of each child?

- What theories, philosophies and understandings shape and assist my work ?

- What aspects of my work are not helped by the theories and guidance that I usually draw on to make sense of what I do?

- What questions do I have about my work?

- What am I challenged by? What am I curious about? What am I confronted by?

- Are there other theories or knowledge that could help me to understand better what I have observed or experienced? What are they?

(DEEWR,2009:13)

Choose one of the simple questions below to get started right now and conquer that critical reflection fear!

- What are you confident is working well in your day to day practice?

- What have you identified isn’t working well for you?

- What might you consider changing?

- How could you find out more about something to make it work better?

- In what areas would you like to grow more as an educator?

I know it can be confronting and we already have so much paperwork to do that this can just seem like a waste of valuable time but without regular critical reflection processes in any profession it can be difficult to grow, to learn new things, to explore different theories and perspectives and to engage in assertive yet constructive discussions with our colleagues.

Please keep in mind that it can be a very fine line between a conversation that discusses different perspectives and methods to shaming someone for their own viewpoint or continually arguing that your way is the only right way. One of the goals of reflective practice is certainly to help us improve and make changes but it doesn't always mean you have to change what you are already doing – you are simply collecting the information you need to make a decision about what you need as you move forward in your role. Perhaps you will find that you are feeling confident and on track with that particular practice, process or direction and can now move on to explore others areas as you ask more reflective questions of yourself and others around you.