The Concept of Political Culture Essay

Culture is a set of beliefs, values, and norms shared by members of society. It largely defines individuals’ attitudes and behaviors, and it is possible to say that, simultaneously, each person can contribute to its development. The same can be said about a political culture because beliefs and ideological symbols are its core elements. However, the nature of political culture is even more complicated than it may appear, and a significant number of scholars of theorists continue to debate over the forces shaping it. Is this culture created by civilians or by elite groups? What role do the mass media play in its design? This paper has the purpose of answering these questions by describing the concept of political culture and analyzing it based on the evidence provided by Andrew Heywood in his book Politics .

The definition of the term “political culture” is slightly different from the definition of culture in a broad sense. As Heywood (2013) states, the concept refers to a set of individuals’ psychological orientations or a “pattern of orientations” to various political phenomena and entities, such as governments, parties, and so forth (p. 172). At the same time, beliefs and attitudes still play a significant role in forming political culture. Notably, Heywood (2013) claims that individuals’ short-term and immediate reactions to particular events are the components of public opinion, whereas political culture is primarily composite of long-term values. Overall, these cultural values determine the manner in which a person engages in political decision-making and other activities within a specific social system.

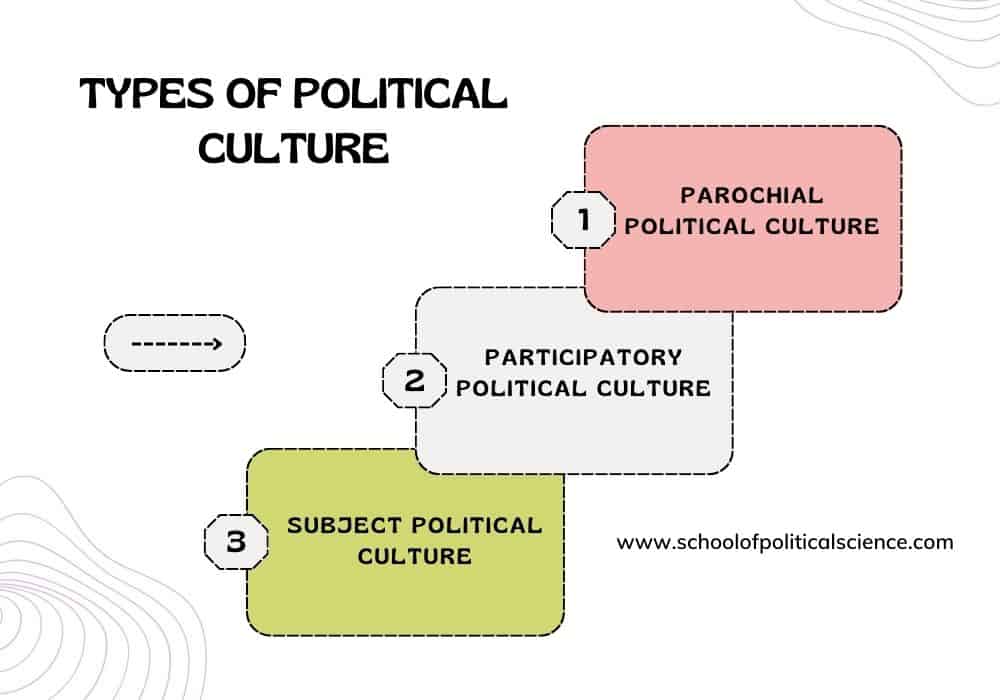

In general, political cultures may be divided into three categories based on the patterns of civic engagement in politics. According to Almond and Verba, whom Heywood (2013) cites in his book, they include a participant, a subject, and parochial political cultures. The former type is more closely associated with democracy because it implies that citizens show an active interest in politics and a willingness to participate in it. The subject culture is defined as more passive and indicates “the recognition that they [citizens] have only a very limited capacity to influence government” (Heywood, 2013, p. 172). Lastly, the parochial culture is characterized by the least active level of engagement, meaning that citizens do not show a willingness to participate in politics or cannot do so.

Normally, different states combine the features of a few types of political cultures, whereas the participant culture may be regarded as an ideal. However, Heywood (2013) notes that this approach to explaining the political culture was highly criticized because the argument about the level of civic participation “rests on the unproven assumption that political attitudes and values shape behavior, and not the other way around” (p. 173). Additionally, such a view does not take into account that the culture may include a multitude of worldviews and ideas with different social groups having their own political interests, as well as attitudes to existing political and social systems.

In contrast, Marx suggested that every culture is class-specific, which means that it is based on the shared values of individuals who have similar experiences and behaviors (Heywood, 2013). Therefore, one political culture may comprise as many value sets as there are social-economic groups within a society. At the same time, Marx also stated that ideologies held by more powerful social groups, such as bourgeois, tend to dominate but, in order to be successful and reduce competition, they have to reconcile with ideas and values of subordinate classes and include them in the agenda.

Also, another prominent theorist of the 20th century mentioned by Heywood (2013), Antonio Gramsci, declared that elites largely shape the dominant political culture by disseminating their values and pertinent knowledge to other groups through various social institutions, including religion and education.

Mass media can play a vital role in consolidating ideologies as well, and the composition of a political culture may be significantly influenced by a group of people who control it. Heywood (2013) observes that the effects of mass media on governance and politics as such can be both favorable and adverse. Firstly, they may be used as a tool to promote stakeholder accountability and increase transparency within governments and advocate for the needs and interests of various social groups. At the same time, they may be used as an instrument of misinformation aimed to maintain a political status quo and reduce political pluralism. Thus, it may either improve or lower the level of civic participation in politics.

Overall, based on the information provided by Heywood (2013) in Politics , it may be concluded that the relationships of individuals with political culture are based on mutual influences on each other. On the one hand, a culture may be created by an elite or a dominant, the most powerful social group and then promoted to others through various means. On the other hand, distinct classes may have equal opportunities to contribute to changes in politics by engaging in debate and other politically relevant activities.

However, it is important to note that mass media and freedom of speech play a vital role in the mobilization of diverse social groups and the development of political literacy. Therefore, the independence of various mass media and other social institutions is correlated with political pluralism and may be considered a sign of democracy and the health of the political system.

Heywood, A. (2013). Politics (4 th ed.). Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, July 18). The Concept of Political Culture. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-concept-of-political-culture/

"The Concept of Political Culture." IvyPanda , 18 July 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/the-concept-of-political-culture/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'The Concept of Political Culture'. 18 July.

IvyPanda . 2021. "The Concept of Political Culture." July 18, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-concept-of-political-culture/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Concept of Political Culture." July 18, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-concept-of-political-culture/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Concept of Political Culture." July 18, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-concept-of-political-culture/.

- The Decline of Social Capital

- Public vs. Parochial Schools: The Principle Points of Conflict

- Female Athletes and Culture of Sexual Harassment

- Herbal Medicine and Remedies in Ancient Egypt

- Political Culture Theory and Classification

- Pluralism and Elitism

- Importance of Civic Engagement

- How dimensions of organizational cultures affect Disney Institute

- Political Culture of American Government

- The Diminished Civic Engagement among American Citizens

- Sentimentalism in American Political Culture

- Indirect Public Participation in the United States

- The UK and the US Political Systems

- Political Crisis and Interests in Ukraine

- Egalitarianism and Social Equality in Cohen's View

Political Culture: Meaning, Features, 3 Types, and importance

In order to gain legitimacy, the proper management of the authority of any political system and the empathy of the people with a positive and supportive view of that authority are required.

In some political systems this view is seen, but lacking in some places. Somewhere, citizens support the political system unconditionally, and somewhere they want a radical change in the political system.

To get a real picture of the political system, a proper analysis of the attitudes of the people is needed. In this context, discussion of political culture is very important to understand the attitudes and beliefs of people on their political system.

Table of Contents

What is Political Culture?

Political culture is the view, aspirations, and beliefs of most citizens of the country toward political systems. It can be said to be a psychological matter for the people. It is also the type of people’s mentality in relation to political activities, not political activities itself.

Must Read- Meaning and 7 Most Important Agents Of Political Socialization

Different types of political cultures exist among the people of different states. In this context, it is to be noted that the tradition of British citizens, the protests among French nationals, and the patriotism among American citizens are strongly present. These are one of the characteristics of the political culture of those countries.

It is changing oriented, but this is changing slowly. Persons’ perceptions change as new experiences unfold.

Depending on the city-life experiences of people coming from village to city and living in the city, there are rapid changes in attitudes. But cultural attitudes or values change very slowly. Hence, the attitude towards political action reflects fairly permanent aspects of political culture.

Features of Political Culture

- The views of the people regarding the world of politics are the subject of political culture, but not the various events organized in world politics. So it can be called the psychological dimension of politics.

- In the political culture, the attitude of both the political ideal and the effective system of the state is expressed.

- It consists of empirical concepts of political life and values that are worth pursuing in political life, and they can be emotional, and perceptive.

- If there is a kind of attitude among the people about important political issues in the political culture, then there is political stability. It is easy to get rid of the crisis if people’s attitudes are favorable to political institutions during the crisis period in the country.

- Political culture does not remain unchanged. It is also constantly reorganized in terms of cultural change in society. With the arrival of foreigners to live, a revolution, war, or any other major change can completely change the political culture of a state.

Types of Political Culture

The nature, existence, and importance of different aspects of political culture vary from one society to another. So the political culture of all countries is not one. These are classified on the basis of these questions whether members of society take an active role in political activities, expect to benefit from public dialogue, whether people can take part in government processes, or know government activities.

Almond and Verba classified political culture into three types. These are:

Parochial Political Culture

Participatory political culture, subject political culture.

Generally, in underdeveloped countries and in the traditional social system, there is a lack of consciousness and interest or widespread indifference among individuals regarding political issues.

In the context of the political way of life and the national political system, there is a strong disregard for the countrymen which leads to the formation of a parochial political culture.

To end such a culture, the need for a wide spreading of education and the spread of political communication is necessary. There are still many regions in Asia and Africa where parochial political culture can be seen.

In a participatory political culture, every citizen actively takes an active role in political affairs. Individuals consider themselves active members of the country’s existing political system.

The participation and evaluation of the individual in the traditional political system is very deep and important in such political culture. Here the individual is always aware of his rights and duties. Great Britain and USA are great examples of participatory political culture.

In this kind of political culture, the role of the people in political affairs is significant. The public is fully aware of the political system prevailing here and the effect of state action on their way of life.

Despite the existence of enthusiasm for political life, the people here make no attempt to influence the decision-making process. Rather, most of the government’s decisions are accepted without authority. This tendency in public affairs for the public interest is attributed to this kind of inactive political culture.

Is the political culture inherited?

The individual does not inherit the political culture by birth. That means it is not a matter of birthright. It is created within the individual through political socialization. The social and political systems in which the person is born, the particular political values and attitudes that transcend the individual.

Individuals are connected with the political parties, other political organizations or institutions, the pressing groups, the state structure, and its functions, within the existing political system.

In this way, the individual becomes increasingly connected and united with the symbols and values of the existing society and political system. This process continues throughout the life of the individual. And this is how political culture emerges within the individual.

Must Read- Pressure Group: Meaning, Definitions, Features, & 4Types

What is the Relation between Political Systems and Political Culture?

The interaction between the political system and the political culture is very close. There can be broad consensus among the people regarding the existing political system and its basic structure. In that case, the political system is strong and stable.

On the contrary, the structure of the existing political system, with disagreement among the people in the context of the tasks, poses a serious hostility to the political system. As a result, the foundation of that political system weakens.

Importance of Political Culture

In any country’s political system, political culture is regarded as important. The political values, beliefs, and attitudes of the country or nation are reflected through the political culture. Social culture is especially important in people’s social lives. Similarly, the importance and significance of the political culture of the people is immense.

Let me share with you what you have learned from “ Political Culture: Meaning, Features, 4 Types, And Importance “.

- Meaning, Characteristics, And 5 Types Of Sovereignty

- Political Theory And Why Should We Study Political Theory?

- 3 Most Important Types of Political Theory

- The Resurgence of Political Theory

- Meaning, History, Features, and Importance of Political Philosophy

Sharing is Caring :)

9 thoughts on “Political Culture: Meaning, Features, 3 Types, and importance”

I feel really complicated!

I want components of political culture

Please assist me contributions of political culture to the political behaviour of the society

This is so amazing.

I want the examples of political culture.

Nice it’s really helped me very much.

That Was intereste.thank you.

Thow that Was intereste.thank you. How shape the political calture of the societ?

How can we shape the political calture of the societies ?

if it have included some examples to elaborate those political systems it is more important. great work.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

6.1 Political Culture

Learning objectives.

After reading this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- What is a nation’s political culture, and why is it important?

- What are the characteristics of American political culture?

- What are the values and beliefs that are most ingrained in American citizens?

- What constitutes a political subculture, and why are subcultures important?

This section defines political culture and identifies the core qualities that distinguish American political culture, including the country’s traditions, folklore, and heroes. The values that Americans embrace, such as individualism and egalitarianism, will be examined as they relate to cultural ideals.

What Is Political Culture?

Political culture can be thought of as a nation’s political personality. It encompasses the deep-rooted, well-established political traits that are characteristic of a society. Political culture takes into account the attitudes, values, and beliefs that people in a society have about the political system, including standard assumptions about the way that government works. As political scientist W. Lance Bennett notes, the components of political culture can be difficult to analyze. “They are rather like the lenses in a pair of glasses: they are not the things we see when we look at the world; they are the things we see with” (Bennett, 1980). Political culture helps build community and facilitate communication because people share an understanding of how and why political events, actions, and experiences occur in their country.

Political culture includes formal rules as well as customs and traditions, sometimes referred to as “habits of the heart,” that are passed on generationally. People agree to abide by certain formal rules, such as the country’s constitution and codified laws. They also live by unstated rules: for example, the willingness in the United States to accept the outcomes of elections without resorting to violence. Political culture sets the boundaries of acceptable political behavior in a society (Elazar, 1994).

While the civic culture in the United States has remained relatively stable over time, shifts have occurred as a result of transforming experiences, such as war, economic crises, and other societal upheavals, that have reshaped attitudes and beliefs (Inglehart, 1990). Key events, such as the Civil War, World War I, World War II, the Great Depression, the Vietnam War, the civil rights movement, and the terrorist attacks of 9/11 have influenced the political worldviews of American citizens, especially young people, whose political values and attitudes are less well established.

American Political Culture

Political culture consists of a variety of different elements. Some aspects of culture are abstract, such as political beliefs and values. Other elements are visible and readily identifiable, such as rituals, traditions, symbols, folklore, and heroes. These aspects of political culture can generate feelings of national pride that form a bond between people and their country. Political culture is not monolithic. It consists of diverse subcultures based on group characteristics such as race, ethnicity, and social circumstances, including living in a particular place or in a certain part of the country. We will now examine these aspects of political culture in the American context.

Beliefs are ideas that are considered to be true by a society. Founders of the American republic endorsed both equality, most notably in the Declaration of Independence, and liberty, most prominently in the Constitution. These political theories have become incorporated into the political culture of the United States in the central beliefs of egalitarianism and individualism.

Egalitarianism is the doctrine emphasizing the natural equality of humans, or at least the absence of a preexisting superiority of one set of humans above another. This core American belief is found in the preamble to the Declaration of Independence, which states that “all men are created equal” and that people are endowed with the unalienable rights to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Americans endorse the intrinsic equal worth of all people. Survey data consistently indicate that between 80 percent and 90 percent of Americans believe that it is essential to treat all people equally, regardless of race or ethnic background (Hunter & Bowman, 1996; Pew Research Center, 2009).

The principle of individualism stresses the centrality and dignity of individual people. It privileges free action and people’s ability to take the initiative in making their own lives as well as those of others more prosperous and satisfying. In keeping with the Constitution’s preoccupation with liberty, Americans feel that children should be taught to believe that individuals can better themselves through self-reliance, hard work, and perseverance (Hunter & Bowman, 1996).

The beliefs of egalitarianism and individualism are in tension with one another. For Americans today, this contradiction tends to be resolved by an expectation of equality of opportunity , the belief that each individual has the same chance to get ahead in society. Americans tend to feel that most people who want to get ahead can make it if they’re willing to work hard (Pew Research Center, 1999). Americans are more likely to promote equal political rights, such as the Voting Rights Act’s stipulation of equal participation for all qualified voters, than economic equality, which would redistribute income from the wealthy to the poor (Wilson, 1997).

Beliefs form the foundation for values , which represent a society’s shared convictions about what is just and good. Americans claim to be committed to the core values of individualism and egalitarianism. Yet there is sometimes a significant disconnect between what Americans are willing to uphold in principle and how they behave in practice. People may say that they support the Constitutional right to free speech but then balk when they are confronted with a political extremist or a racist speaking in public.

Core American political values are vested in what is often called the American creed . The creed, which was composed by New York State Commissioner of Education Henry Sterling Chapin in 1918, refers to the belief that the United States is a government “by the people, for the people, whose just powers are derived from the consent of the governed.” The nation consists of sovereign states united as “a perfect Union” based on “the principles of freedom, equality, justice, and humanity.” American exceptionalism is the view that America’s exceptional development as a nation has contributed to its special place is the world. It is the conviction that the country’s vast frontier offered boundless and equal opportunities for individuals to achieve their goals. Americans feel strongly that their nation is destined to serve as an example to other countries (Hunter & Bowman, 1996). They believe that the political and economic systems that have evolved in this country are perfectly suited in principle to permit both individualism and egalitarianism.

Consequently, the American creed also includes patriotism : the love of one’s country and respect for its symbols and principles. The events of 9/11 ignited Americans’ patriotic values, resulting in many public displays of support for the country, its democratic form of government, and authority figures in public-service jobs, such as police and firefighters. The press has scrutinized politicians for actions that are perceived to indicate a lack of patriotism, and the perception that a political leader is not patriotic can generate controversy. In the 2008 presidential election, a minor media frenzy developed over Democratic presidential candidate Barack Obama’s “patriotism problem.” The news media debated the significance of Obama’s not wearing a flag lapel pin on the campaign trail and his failure to place his hand over his heart during the playing of the national anthem.

Barack Obama’s Patriotism

(click to see video)

A steak fry in Iowa during the 2008 Democratic presidential primary sparked a debate over candidate Barack Obama’s patriotism. Obama, standing with opponents Bill Richardson and Hillary Clinton, failed to place his hand over his heart during the playing of the national anthem. In the background is Ruth Harkin, wife of Senator Tom Harkin, who hosted the event.

Another core American value is political tolerance , the willingness to allow groups with whom one disagrees to exercise their constitutionally guaranteed freedoms, such as free speech. While many people strongly support the ideal of tolerance, they often are unwilling to extend political freedoms to groups they dislike. People acknowledge the constitutional right of racist groups, such as skinheads, to demonstrate in public, but will go to great lengths to prevent them from doing so (Sullivan, Piereson, & Marcus, 1982).

Democratic political values are among the cornerstones of the American creed. Americans believe in the rule of law : the idea that government is based on a body of law, agreed on by the governed, that is applied equally and justly. The Constitution is the foundation for the rule of law. The creed also encompasses the public’s high degree of respect for the American system of government and the structure of its political institutions.

Capitalist economic values are embraced by the American creed. Capitalist economic systems emphasize the need for a free-enterprise system that allows for open business competition, private ownership of property, and limited government intervention in business affairs. Underlying these capitalist values is the belief that, through hard work and perseverance, anyone can be financially successful (McClosky & Zaller, 1987).

Tea Party supporters from across the country staged a “March on Washington” to demonstrate their opposition to government spending and to show their patriotism.

Wikimedia Commons – CC BY-SA 3.0.

The primacy of individualism may undercut the status quo in politics and economics. The emphasis on the lone, powerful person implies a distrust of collective action and of power structures such as big government, big business, or big labor. The public is leery of having too much power concentrated in the hands of a few large companies. The emergence of the Tea Party, a visible grassroots conservative movement that gained momentum during the 2010 midterm elections, illustrates how some Americans become mobilized in opposition to the “tax and spend” policies of big government (Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, 2001). While the Tea Party shunned the mainstream media because of their view that the press had a liberal bias, they received tremendous coverage of their rallies and conventions, as well as their candidates. Tea Party candidates relied heavily on social media, such as Facebook and Twitter, to get their anti–big government message out to the public.

Rituals, Traditions, and Symbols

Rituals, traditions, and symbols are highly visible aspects of political culture, and they are important characteristics of a nation’s identity. Rituals , such as singing the national anthem at sporting events and saluting the flag before the start of a school day, are ceremonial acts that are performed by the people of a nation. Some rituals have important symbolic and substantive purposes: Election Night follows a standard script that ends with the vanquished candidate congratulating the opponent on a well-fought battle and urging support and unity behind the victor. Whether they have supported a winning or losing candidate, voters feel better about the outcome as a result of this ritual (Ginsberg & Weissberg, 1978).The State of the Union address that the president makes to Congress every January is a ritual that, in the modern era, has become an opportunity for the president to set his policy agenda, to report on his administration’s accomplishments, and to establish public trust. A more recent addition to the ritual is the practice of having representatives from the president’s party and the opposition give formal, televised reactions to the address.

President Barack Obama gives the 2010 State of the Union address. The ritual calls for the president to be flanked by the Speaker of the House of Representatives (Nancy Pelosi) and the vice president (Joe Biden). Members of Congress and distinguished guests fill the House gallery.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

Political traditions are customs and festivities that are passed on from generation to generation, such as celebrating America’s founding on the Fourth of July with parades, picnics, and fireworks. Symbols are objects or emblems that stand for a nation. The flag is perhaps the most significant national symbol, especially as it can take on enhanced meaning when a country experiences difficult times. The bald eagle was officially adopted as the country’s emblem in 1787, as it is considered a symbol of America’s “supreme power and authority.”

The Statue of Liberty stands in New York Harbor, an 1844 gift from France that is a symbol welcoming people from foreign lands to America’s shores.

Severin St. Martin – Statue of Liberty from Air – CC BY 2.0.

Political folklore , the legends and stories that are shared by a nation, constitutes another element of culture. Individualism and egalitarianism are central themes in American folklore that are used to reinforce the country’s values. The “rags-to-riches” narratives of novelists—the late-nineteenth-century writer Horatio Alger being the quintessential example—celebrate the possibilities of advancement through hard work.

Much American folklore has grown up around the early presidents and figures from the American Revolution. This folklore creates an image of men, and occasionally women, of character and strength. Most folklore contains elements of truth, but these stories are usually greatly exaggerated.

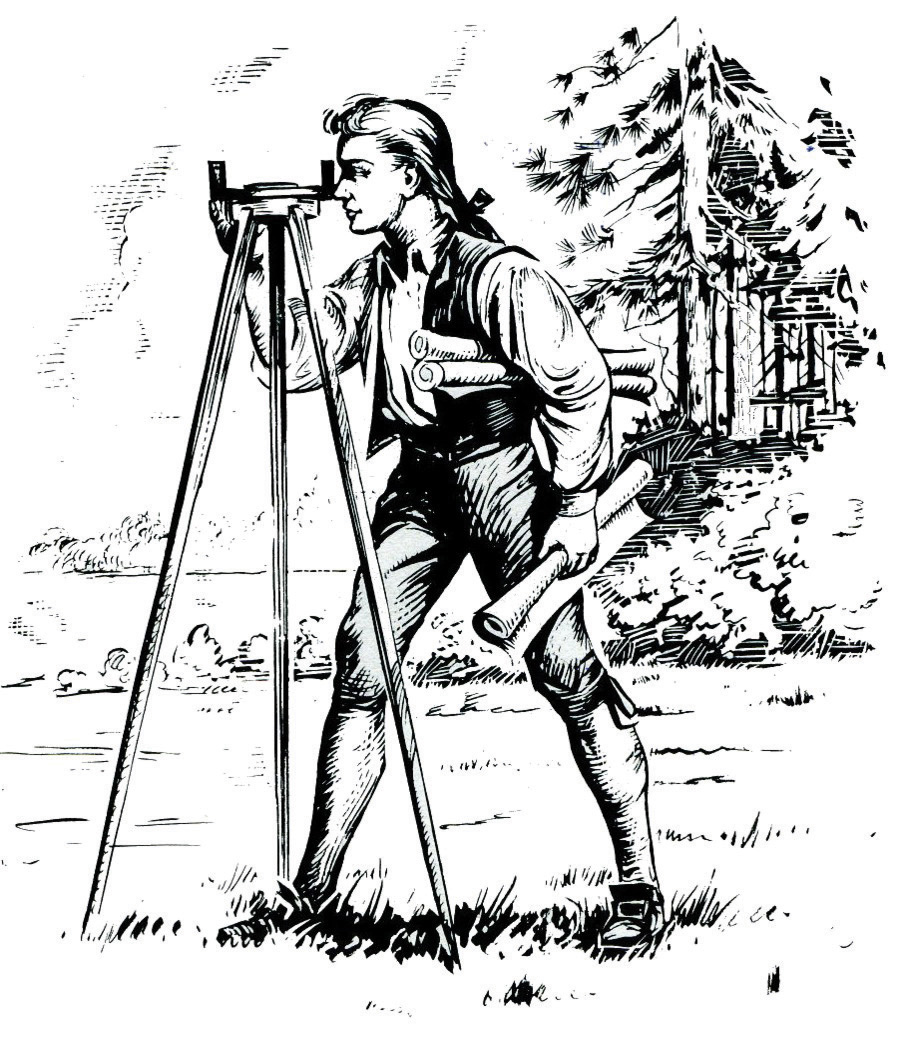

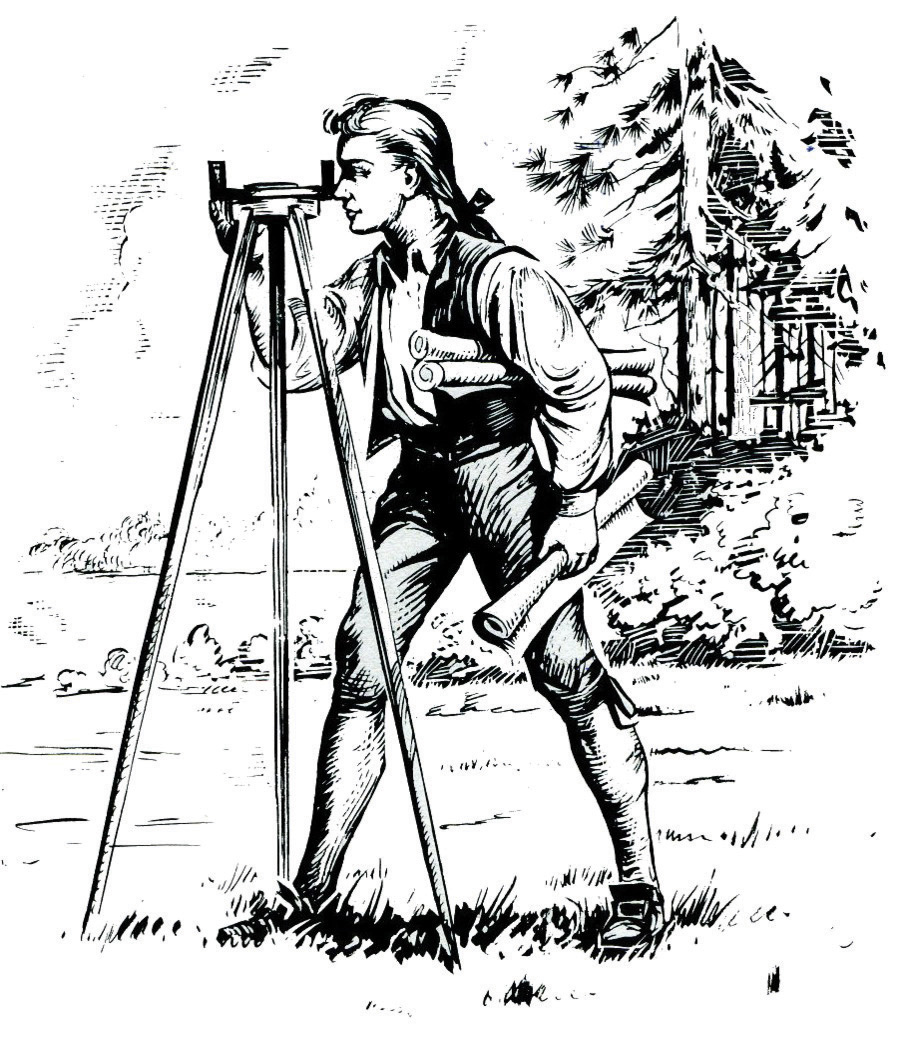

There are many folktales about young George Washington, including that he chopped down a cherry tree and threw a silver dollar across the Potomac River. These stories were popularized by engravings like this one by John C. Mccabe depicting Washington working as a land surveyor.

The first American president, George Washington, is the subject of folklore that has been passed on to school children for more than two hundred years. Young children learn about Washington’s impeccable honesty and, thereby, the importance of telling the truth, from the legend of the cherry tree. When asked by his father if he had chopped down a cherry tree with his new hatchet, Washington confessed to committing the deed by replying, “Father, I cannot tell a lie.” This event never happened and was fabricated by biographer Parson Mason Weems in the late 1700s (George Washington’s Mount Vernon, 2011). Legend also has it that, as a boy, Washington threw a silver dollar across the Potomac River, a story meant to illustrate his tremendous physical strength. In fact, Washington was not a gifted athlete, and silver dollars did not exist when he was a youth. The origin of this folklore is an episode related by his step-grandson, who wrote that Washington had once thrown a piece of slate across a very narrow portion of the Rappahannock River in Virginia (George Washington’s Mount Vernon, 2011).

Heroes embody the human characteristics most prized by a country. A nation’s political culture is in part defined by its heroes who, in theory, embody the best of what that country has to offer. Traditionally, heroes are people who are admired for their strength of character, beneficence, courage, and leadership. People also can achieve hero status because of other factors, such as celebrity status, athletic excellence, and wealth.

Shifts in the people whom a nation identifies as heroes reflect changes in cultural values. Prior to the twentieth century, political figures were preeminent among American heroes. These included patriotic leaders, such as American-flag designer Betsy Ross; prominent presidents, such as Abraham Lincoln; and military leaders, such as Civil War General Stonewall Jackson, a leader of the Confederate army. People learned about these leaders from biographies, which provided information about the valiant actions and patriotic attitudes that contributed to their success.

Today American heroes are more likely to come from the ranks of prominent entertainment, sports, and business figures than from the world of politics. Popular culture became a powerful mechanism for elevating people to hero status beginning around the 1920s. As mass media, especially motion pictures, radio, and television, became an important part of American life, entertainment and sports personalities who received a great deal of publicity became heroes to many people who were awed by their celebrity (Greenstein, 1969).

In the 1990s, business leaders, such as Microsoft’s Bill Gates and General Electric’s Jack Welch, were considered to be heroes by some Americans who sought to achieve material success. The tenure of business leaders as American heroes was short-lived, however, as media reports of the lavish lifestyles and widespread criminal misconduct of some corporation heads led people to become disillusioned. The incarceration of Wall Street investment advisor Bernard Madoff made international headlines as he was alleged to have defrauded investors of billions of dollars (Yin, 2001).

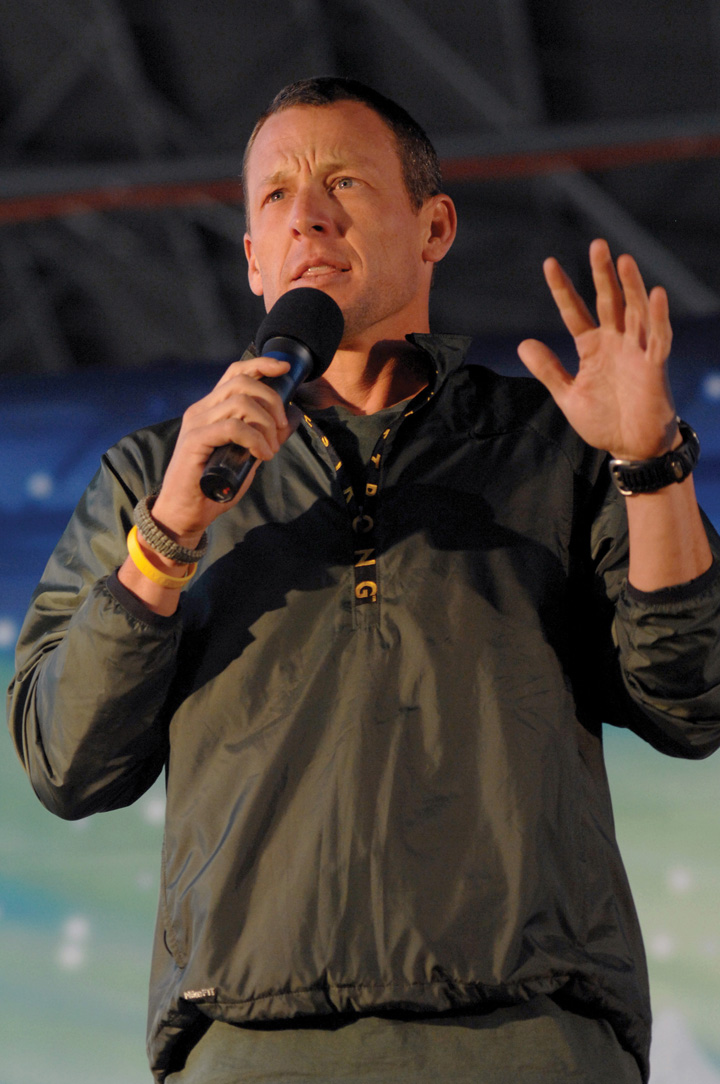

Sports figures feature prominently among American heroes, especially during their prime. Cyclist Lance Armstrong is a hero to many Americans because of his unmatched accomplishment of winning seven consecutive Tour de France titles after beating cancer. However, heroes can face opposition from those who seek to discredit them: Armstrong, for example, has been accused of doping to win races, although he has never failed a drug test.

Cyclist Lance Armstrong is considered by many to be an American hero because of his athletic accomplishments and his fight against cancer. He also has been the subject of unrelenting media reports that attempt to deflate his hero status.

NBA basketball player Michael Jordan epitomizes the modern-day American hero. Jordan’s hero status is vested in his ability to bridge the world of sports and business with unmatched success. The media promoted Jordan’s hero image intensively, and he was marketed commercially by Nike, who produced his “Air Jordans” shoes (Walters, 1997). His unauthorized 1999 film biography is titled Michael Jordan: An American Hero , and it focuses on how Jordan triumphed over obstacles, such as racial prejudice and personal insecurities, to become a role model on and off the basketball court. Young filmgoers watched Michael Jordan help Bugs Bunny defeat evil aliens in Space Jam . In the film Like Mike , pint-sized rapper Lil’ Bow Wow plays an orphan who finds a pair of Michael Jordan’s basketball shoes and is magically transformed into an NBA star. Lil’ Bow Wow’s story has a happy ending because he works hard and plays by the rules.

The 9/11 terrorist attacks prompted Americans to make heroes of ordinary people who performed in extraordinary ways in the face of adversity. Firefighters and police officers who gave their lives, recovered victims, and protected people from further threats were honored in numerous ceremonies. Also treated as heroes were the passengers of Flight 93 who attempted to overtake the terrorists who had hijacked their plane, which was believed to be headed for a target in Washington, DC. The plane crashed in a Pennsylvania field.

Subcultures

Political subcultures are distinct groups, associated with particular beliefs, values, and behavior patterns, that exist within the overall framework of the larger culture. They can develop around groups with distinct interests, such as those based on age, sex, race, ethnicity, social class, religion, and sexual preference. Subcultures also can be geographically based. Political scientist Daniel Elazar identified regional political subcultures, rooted in American immigrant settlement patterns, that influenced the way that government was constituted and practiced in different locations across the nation. The moral political subculture, which is present in New England and the Midwest, promotes the common good over individual values. The individual political subculture, which is evident in the middle Atlantic states and the West, is more concerned with private enterprise than societal interests. The traditional political subculture, which is found in the South, reflects a hierarchical societal structure in which social and familial ties are central to holding political power (Elazar, 1972). Political subcultures can also form around social and artistic groups and their associated lifestyles, such as the heavy metal and hip-hop music subcultures.

Media Frames

The Hip-Hop Subculture

A cohort of black Americans has been labeled the hip-hop generation by scholars and social observers. The hip-hop generation is a subculture of generation X (people born between 1965 and 1984) that identifies strongly with hip-hop music as a unifying force. Its heroes come from the ranks of prominent music artists, including Grandmaster Flash, Chuck D, Run DMC, Ice Cube, Sister Souljah, Nikki D, and Queen Latifah. While a small number of people who identify with this subculture advocate extreme politics, including violence against political leaders, the vast majority are peaceful, law-abiding citizens (Kitwana, 2002).

The hip-hop subculture emerged in the early 1970s in New York City. Hip-hop music began with party-oriented themes, but by 1982 it was focusing heavily on political issues. Unlike the preceding civil rights generation—a black subculture of baby boomers (people born immediately after World War II) that concentrated on achieving equal rights—the hip-hop subculture does not have an overarching political agenda. The messages passed on to the subculture by the music are highly varied and often contradictory. Some lyrics express frustration about the poverty, lack of educational and employment opportunities, and high crime rates that plague segments of the black community. Other songs provide public service messages, such as those included on the Stop the Violence album featuring Public Enemy and MC Lyte, and Salt-N-Pepa’s “Let’s Talk about AIDS.” Music associated with the gangsta rap genre, which was the product of gang culture and street wars in South Central Los Angeles, promotes violence, especially against women and authority figures, such as the police. It is from these lyrics that the mass media derive their most prominent frames when they cover the hip-hop subculture (Marable, 2002).

Media coverage of the hip-hop subculture focuses heavily on negative events and issues, while ignoring the socially constructive messages of many musicians. The subculture receives most of its media attention in response to the murder of prominent artists, such as Tupac Shakur and Notorious B.I.G., or the arrest of musicians for violating the law, usually for a weapons- or drug-related charge. A prominent news frame is how violence in the music’s lyrics translates into real-life violence. As hip-hop music became more popular with suburban white youth in the 1990s, the news media stepped up its warnings about the dangers of this subculture.

Media reports of the hip-hop subculture also coincide with the release of successful albums. Since 1998, hip-hop and rap have been the top-selling record formats. The dominant news frame is that the hip-hop subculture promotes selfish materialist values. This is illustrated by news reports about the cars, homes, jewelry, and other commodities purchased by successful musicians and their promoters (Lewis, 2003).

Media coverage of hip-hop tends to downplay the positive aspects of the subculture.

Although the definition of political culture emphasizes unifying, collective understandings, in reality, cultures are multidimensional and often in conflict. When subcultural groups compete for societal resources, such as access to government funding for programs that will benefit them, cultural cleavages and clashes can result. As we will see in the section on multiculturalism, conflict between competing subcultures is an ever-present fact of American life.

Multiculturalism

One of the hallmarks of American culture is its racial and ethnic diversity. In the early twentieth century, the playwright Israel Zangwill coined the phrase “ melting pot ” to describe how immigrants from many different backgrounds came together in the United States. The melting pot metaphor assumed that over time the distinct habits, customs, and traditions associated with particular groups would disappear as people assimilated into the larger culture. A uniquely American culture would emerge that accommodated some elements of diverse immigrant cultures in a new context (Fuchs, 1990). For example, American holiday celebrations incorporate traditions from other nations. Many common American words originate from other languages. Still, the melting pot concept fails to recognize that immigrant groups do not entirely abandon their distinct identities. Racial and ethnic groups maintain many of their basic characteristics, but at the same time, their cultural orientations change through marriage and interactions with others in society.

Over the past decade, there has been a trend toward greater acceptance of America’s cultural diversity. Multiculturalism celebrates the unique cultural heritage of racial and ethnic groups, some of whom seek to preserve their native languages and lifestyles. The United States is home to many people who were born in foreign countries and still maintain the cultural practices of their homelands.

Multiculturalism has been embraced by many Americans, and it has been promoted formally by institutions. Elementary and secondary schools have adopted curricula to foster understanding of cultural diversity by exposing students to the customs and traditions of racial and ethnic groups. As a result, young people today are more tolerant of diversity in society than any prior generation has been. Government agencies advocate tolerance for diversity by sponsoring Hispanic and Asian American/Pacific Islander heritage weeks. The US Postal Service has introduced stamps depicting prominent Americans from diverse backgrounds.

Americans celebrate their multicultural heritage by maintaining traditions associated with their homelands.

Despite these trends, America’s multiculturalism has been a source of societal tension. Support for the melting pot assumptions about racial and ethnic assimilation still exists (Hunter & Bowman, 1996). Some Americans believe that too much effort and expense is directed at maintaining separate racial and ethnic practices, such as bilingual education. Conflict can arise when people feel that society has gone too far in accommodating multiculturalism in areas such as employment programs that encourage hiring people from varied racial and ethnic backgrounds (Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, 1999).

Enduring Images

The 9/11 Firefighters’ Statue

On 9/11 Thomas E. Franklin, a photographer for Bergen County, New Jersey’s Record , photographed three firefighters, Billy Eisengrein, George Johnson, and Dan McWilliams, raising a flag amid the smoldering rubble of the World Trade Center. Labeled by the press “the photo seen ‘round the world,” his image came to symbolize the strength, resilience, and heroism of Americans in the face of a direct attack on their homeland.

Developer Bruce Ratner commissioned a nineteen-foot-tall, $180,000 bronze statue based on the photograph to stand in front of the New York City Fire Department (FDNY) headquarters in Brooklyn. When the statue prototype was unveiled, it revealed that the faces of two of the three white firefighters who had originally raised the flag had been replaced with those of black and Hispanic firefighters. Ratner and the artist who designed the statue claimed that the modification of the original image represented an effort to promote America’s multicultural heritage and tolerance for diversity. The change had been authorized by the FDNY leadership (Dreher, 2002).

The modification of the famous photo raised the issue of whether it is valid to alter historical fact in order to promote a cultural value. A heated controversy broke out over the statue. Supporters of the change believed that the statue was designed to honor all firefighters, and that representing their diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds was warranted. Black and Hispanic firefighters were among the 343 who had lost their lives at the World Trade Center. Kevin James of the Vulcan Society, which represents black firefighters, defended the decision by stating, “The symbolism is far more important than representing the actual people. I think the artistic expression of diversity would supersede any concern over factual correctness.” [1]

Opponents claimed that since the statue was not meant to be a tribute to firefighters, but rather a depiction of an actual event, the representation needed to be historically accurate. They drew a parallel to the famous 1945 Associated Press photograph of six Marines raising the flag on Iwo Jima during World War II and the historically precise memorial that was erected in Arlington, Virginia. Opponents also felt that it was wrong to politicize the statue by making it part of a dialogue on race. The proposed statue promoted an image of diversity within the FDNY that did not mirror reality. Of the FDNY’s 11,495 firefighters, 2.7 percent are black and 3.2 percent are Latino, percentages well below the percentage these groups represent in the overall population.

Some people suggested a compromise—two statues. They proposed that the statue based on the Franklin photo should reflect historical reality; a second statue, celebrating multiculturalism, should be erected in front of another FDNY station and include depictions of rescue workers of diverse backgrounds at the World Trade Center site. Plans for any type of statue were abandoned as a result of the controversy.

The iconic photograph of 9/11 firefighters raising a flag near the rubble of the World Trade Center plaza is immortalized in a US postage stamp. Thomas Franklin, the veteran reporter who took the photo, said that the image reminded him of the famous Associated Press image of Marines raising the American flag on Iwo Jima during World War II.

Key Takeaways

Political culture is defined by the ideologies, values, beliefs, norms, customs, traditions, and heroes characteristic of a nation. People living in a particular political culture share views about the nature and operation of government. Political culture changes over time in response to dramatic events, such as war, economic collapse, or radical technological developments. The core American values of democracy and capitalism are vested in the American creed. American exceptionalism is the idea that the country has a special place in the world because of the circumstances surrounding its founding and the settling of a vast frontier.

Rituals, traditions, and symbols bond people to their culture and can stimulate national pride. Folklore consists of stories about a nation’s leaders and heroes; often embellished, these stories highlight the character traits that are desirable in a nation’s citizens. Heroes are important for defining a nation’s political culture.

America has numerous subcultures based on geographic region; demographic, personal, and social characteristics; religious affiliation, and artistic inclinations. America’s unique multicultural heritage is vested in the various racial and ethnic groups who have settled in the country, but conflicts can arise when subgroups compete for societal resources.

- What do you think the American flag represents? Would it bother you to see someone burn an American flag? Why or why not?

- What distinction does the text make between beliefs and values? Are there things that you believe in principle should be done that you might be uncomfortable with in practice? What are they?

- Do you agree that America is uniquely suited to foster freedom and equality? Why or why not?

- What characteristics make you think of someone as particularly American? Does race or cultural background play a role in whether you think of a person as American?

Bennett, W. L., Public Opinion in American Politics (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1980), 368.

Dreher, R., “The Bravest Speak,” National Review Online , January 16, 2002.

Elazar, D. J., American Federalism: A View From the States, 2nd ed. (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1972).

Elazar, D. J., The American Mosaic (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1994).

Fuchs, L. H., The American Kaleidoscope . (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1990).

George Washington’s Mount Vernon, “Did George Washington really throw a silver dollar across the Potomac River?,” accessed February 3, 2011, http://www.mountvernon.org/knowledge/index.cfm/fuseaction/view/KnowledgeID/20 .

George Washington’s Mount Vernon, “Is it true that George Washington chopped down a cherry tree when he was a boy?,” accessed February 3, 2011, http://www.mountvernon.org/knowledge/index.cfm/fuseaction/view/KnowledgeID/21 .

Ginsberg, B. and Herbert Weissberg, “Elections and the Mobilization of Popular Support,” American Journal of Political Science 22, no.1 (1978): 31–55.

Greenstein, F. I., Children and Politics (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1969).

Hunter, J. D. and Carl Bowman, The State of Disunion (Charlottesville, VA: In Media Res Educational Foundation, 1996).

Inglehart, R., Culture Shift in Advanced Industrial Society (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990).

Kitwana, B., The Hip-Hop Generation (New York: Basic Civitas Books, 2002).

Lewis, A., “Vilification of Black Youth Culture by the Media” (master’s thesis, Georgetown University, 2003).

Marable, M., “The Politics of Hip-Hop,” The Urban Think Tank , 2 (2002). http://www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/45a/594.html .

McClosky, H. and John Zaller, The American Ethos (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987).

Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, Retro-Politics: The Political Typology (Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, November 11, 1999).

Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, Values Survey (Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, March 2009).

Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, Views of Business and Regulation Remain Unchanged (Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, February 21, 2001).

Sullivan, J. L., James Piereson, and George E. Marcus, Political Tolerance and American Democracy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982).

Walters, P., “Michael Jordan: The New American Hero” (Charlottesville VA: The Crossroads Project, 1997).

Wilson, R. W., “American Political Culture in Comparative Perspective,” Political Psychology , 18, no. 2 (1997): 483–502.

Yin, S., “Shifting Careers,” American Demographics , 23, no. 12 (December 2001): 39–40.

- “Ground Zero Statue Criticized for ‘Political Correctness,’” CNN , January 12, 2002, http//www.cnn.com. ↵

American Government and Politics in the Information Age Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- What is a nation’s political culture, and why is it important?

- What are the characteristics of American political culture?

- What are the values and beliefs that are most ingrained in American citizens?

- What constitutes a political subculture, and why are subcultures important?

This section defines political culture and identifies the core qualities that distinguish American political culture, including the country’s traditions, folklore, and heroes. The values that Americans embrace, such as individualism and egalitarianism, will be examined as they relate to cultural ideals.

What Is Political Culture?

Political culture can be thought of as a nation’s political personality. It encompasses the deep-rooted, well-established political traits that are characteristic of a society. Political culture takes into account the attitudes, values, and beliefs that people in a society have about the political system, including standard assumptions about the way that government works. As political scientist W. Lance Bennett notes, the components of political culture can be difficult to analyze. “They are rather like the lenses in a pair of glasses: they are not the things we see when we look at the world; they are the things we see with” (Bennett, 1980). Political culture helps build community and facilitate communication because people share an understanding of how and why political events, actions, and experiences occur in their country.

Political culture includes formal rules as well as customs and traditions, sometimes referred to as “habits of the heart,” that are passed on generationally. People agree to abide by certain formal rules, such as the country’s constitution and codified laws. They also live by unstated rules: for example, the willingness in the United States to accept the outcomes of elections without resorting to violence. Political culture sets the boundaries of acceptable political behavior in a society (Elazar, 1994).

While the civic culture in the United States has remained relatively stable over time, shifts have occurred as a result of transforming experiences, such as war, economic crises, and other societal upheavals, that have reshaped attitudes and beliefs (Inglehart, 1990). Key events, such as the Civil War, World War I, World War II, the Great Depression, the Vietnam War, the civil rights movement, and the terrorist attacks of 9/11 have influenced the political worldviews of American citizens, especially young people, whose political values and attitudes are less well established.

American Political Culture

Political culture consists of a variety of different elements. Some aspects of culture are abstract, such as political beliefs and values. Other elements are visible and readily identifiable, such as rituals, traditions, symbols, folklore, and heroes. These aspects of political culture can generate feelings of national pride that form a bond between people and their country. Political culture is not monolithic. It consists of diverse subcultures based on group characteristics such as race, ethnicity, and social circumstances, including living in a particular place or in a certain part of the country. We will now examine these aspects of political culture in the American context.

Beliefs are ideas that are considered to be true by a society. Founders of the American republic endorsed both equality, most notably in the Declaration of Independence, and liberty, most prominently in the Constitution. These political theories have become incorporated into the political culture of the United States in the central beliefs of egalitarianism and individualism.

Egalitarianism is the doctrine emphasizing the natural equality of humans, or at least the absence of a preexisting superiority of one set of humans above another. This core American belief is found in the preamble to the Declaration of Independence, which states that “all men are created equal” and that people are endowed with the unalienable rights to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Americans endorse the intrinsic equal worth of all people. Survey data consistently indicate that between 80 percent and 90 percent of Americans believe that it is essential to treat all people equally, regardless of race or ethnic background (Hunter & Bowman, 1996; Pew Research Center, 2009).

The principle of individualism stresses the centrality and dignity of individual people. It privileges free action and people’s ability to take the initiative in making their own lives as well as those of others more prosperous and satisfying. In keeping with the Constitution’s preoccupation with liberty, Americans feel that children should be taught to believe that individuals can better themselves through self-reliance, hard work, and perseverance (Hunter & Bowman, 1996).

The beliefs of egalitarianism and individualism are in tension with one another. For Americans today, this contradiction tends to be resolved by an expectation of equality of opportunity , the belief that each individual has the same chance to get ahead in society. Americans tend to feel that most people who want to get ahead can make it if they’re willing to work hard (Pew Research Center, 1999). Americans are more likely to promote equal political rights, such as the Voting Rights Act’s stipulation of equal participation for all qualified voters, than economic equality, which would redistribute income from the wealthy to the poor (Wilson, 1997).

Beliefs form the foundation for values , which represent a society’s shared convictions about what is just and good. Americans claim to be committed to the core values of individualism and egalitarianism. Yet there is sometimes a significant disconnect between what Americans are willing to uphold in principle and how they behave in practice. People may say that they support the Constitutional right to free speech but then balk when they are confronted with a political extremist or a racist speaking in public.

Core American political values are vested in what is often called the American creed . The creed, which was composed by New York State Commissioner of Education Henry Sterling Chapin in 1918, refers to the belief that the United States is a government “by the people, for the people, whose just powers are derived from the consent of the governed.” The nation consists of sovereign states united as “a perfect Union” based on “the principles of freedom, equality, justice, and humanity.” American exceptionalism is the view that America’s exceptional development as a nation has contributed to its special place is the world. It is the conviction that the country’s vast frontier offered boundless and equal opportunities for individuals to achieve their goals. Americans feel strongly that their nation is destined to serve as an example to other countries (Hunter & Bowman, 1996). They believe that the political and economic systems that have evolved in this country are perfectly suited in principle to permit both individualism and egalitarianism.

Consequently, the American creed also includes patriotism : the love of one’s country and respect for its symbols and principles. The events of 9/11 ignited Americans’ patriotic values, resulting in many public displays of support for the country, its democratic form of government, and authority figures in public-service jobs, such as police and firefighters. The press has scrutinized politicians for actions that are perceived to indicate a lack of patriotism, and the perception that a political leader is not patriotic can generate controversy. In the 2008 presidential election, a minor media frenzy developed over Democratic presidential candidate Barack Obama’s “patriotism problem.” The news media debated the significance of Obama’s not wearing a flag lapel pin on the campaign trail and his failure to place his hand over his heart during the playing of the national anthem.

Another core American value is political tolerance , the willingness to allow groups with whom one disagrees to exercise their constitutionally guaranteed freedoms, such as free speech. While many people strongly support the ideal of tolerance, they often are unwilling to extend political freedoms to groups they dislike. People acknowledge the constitutional right of racist groups, such as skinheads, to demonstrate in public, but will go to great lengths to prevent them from doing so (Sullivan, Piereson, & Marcus, 1982).

Democratic political values are among the cornerstones of the American creed. Americans believe in the rule of law : the idea that government is based on a body of law, agreed on by the governed, that is applied equally and justly. The Constitution is the foundation for the rule of law. The creed also encompasses the public’s high degree of respect for the American system of government and the structure of its political institutions.

Capitalist economic values are embraced by the American creed. Capitalist economic systems emphasize the need for a free-enterprise system that allows for open business competition, private ownership of property, and limited government intervention in business affairs. Underlying these capitalist values is the belief that, through hard work and perseverance, anyone can be financially successful (McClosky & Zaller, 1987).

The primacy of individualism may undercut the status quo in politics and economics. The emphasis on the lone, powerful person implies a distrust of collective action and of power structures such as big government, big business, or big labor. The public is leery of having too much power concentrated in the hands of a few large companies. The emergence of the Tea Party, a visible grassroots conservative movement that gained momentum during the 2010 midterm elections, illustrates how some Americans become mobilized in opposition to the “tax and spend” policies of big government (Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, 2001). While the Tea Party shunned the mainstream media because of their view that the press had a liberal bias, they received tremendous coverage of their rallies and conventions, as well as their candidates. Tea Party candidates relied heavily on social media, such as Facebook and Twitter, to get their anti–big government message out to the public.

Rituals, Traditions, and Symbols

Rituals, traditions, and symbols are highly visible aspects of political culture, and they are important characteristics of a nation’s identity. Rituals , such as singing the national anthem at sporting events and saluting the flag before the start of a school day, are ceremonial acts that are performed by the people of a nation. Some rituals have important symbolic and substantive purposes: Election Night follows a standard script that ends with the vanquished candidate congratulating the opponent on a well-fought battle and urging support and unity behind the victor. Whether they have supported a winning or losing candidate, voters feel better about the outcome as a result of this ritual (Ginsberg & Weissberg, 1978). Recently, the trend has shifted away from this and is perhaps creating a shift in American political culture. Donald Trump’s refusal to concede defeat to Joe Biden after the 2020 election spurred the events of January 6, 2021 where supporters of the former president stormed the U.S. Capitol building in an effort to prevent the certification of the election by Congress. This has encouraged those whose candidate didn’t win to seek to discredit the legitimacy of the elected official.

The State of the Union address that the president makes to Congress every January is a ritual that, in the modern era, has become an opportunity for the president to set his policy agenda, to report on his administration’s accomplishments, and to establish public trust. A more recent addition to the ritual is the practice of having representatives from the president’s party and the opposition give formal, televised reactions to the address.

Political traditions are customs and festivities that are passed on from generation to generation, such as celebrating America’s founding on the Fourth of July with parades, picnics, and fireworks. Symbols are objects or emblems that stand for a nation. The flag is perhaps the most significant national symbol, especially as it can take on enhanced meaning when a country experiences difficult times. The bald eagle was officially adopted as the country’s emblem in 1787, as it is considered a symbol of America’s “supreme power and authority.”

Political folklore , the legends and stories that are shared by a nation, constitutes another element of culture. Individualism and egalitarianism are central themes in American folklore that are used to reinforce the country’s values. The “rags-to-riches” narratives of novelists—the late-nineteenth-century writer Horatio Alger being the quintessential example—celebrate the possibilities of advancement through hard work.

Much American folklore has grown up around the early presidents and figures from the American Revolution. This folklore creates an image of men, and occasionally women, of character and strength. Most folklore contains elements of truth, but these stories are usually greatly exaggerated.

The first American president, George Washington, is the subject of folklore that has been passed on to school children for more than two hundred years. Young children learn about Washington’s impeccable honesty and, thereby, the importance of telling the truth, from the legend of the cherry tree. When asked by his father if he had chopped down a cherry tree with his new hatchet, Washington confessed to committing the deed by replying, “Father, I cannot tell a lie.” This event never happened and was fabricated by biographer Parson Mason Weems in the late 1700s (George Washington’s Mount Vernon, 2011). Legend also has it that, as a boy, Washington threw a silver dollar across the Potomac River, a story meant to illustrate his tremendous physical strength. In fact, Washington was not a gifted athlete, and silver dollars did not exist when he was a youth. The origin of this folklore is an episode related by his step-grandson, who wrote that Washington had once thrown a piece of slate across a very narrow portion of the Rappahannock River in Virginia (George Washington’s Mount Vernon, 2011).

Heroes embody the human characteristics most prized by a country. A nation’s political culture is in part defined by its heroes who, in theory, embody the best of what that country has to offer. Traditionally, heroes are people who are admired for their strength of character, beneficence, courage, and leadership. People also can achieve hero status because of other factors, such as celebrity status, athletic excellence, and wealth.

Shifts in the people whom a nation identifies as heroes reflect changes in cultural values. Prior to the twentieth century, political figures were preeminent among American heroes. These included patriotic leaders, such as American-flag designer Betsy Ross; prominent presidents, such as Abraham Lincoln; and military leaders, such as Civil War General Stonewall Jackson, a leader of the Confederate army. People learned about these leaders from biographies, which provided information about the valiant actions and patriotic attitudes that contributed to their success.

Today American heroes are more likely to come from the ranks of prominent entertainment, sports, and business figures than from the world of politics. Popular culture became a powerful mechanism for elevating people to hero status beginning around the 1920s. As mass media, especially motion pictures, radio, and television, became an important part of American life, entertainment and sports personalities who received a great deal of publicity became heroes to many people who were awed by their celebrity (Greenstein, 1969).

In the 1990s, business leaders, such as Microsoft’s Bill Gates and General Electric’s Jack Welch, were considered to be heroes by some Americans who sought to achieve material success. The tenure of business leaders as American heroes was short-lived, however, as media reports of the lavish lifestyles and widespread criminal misconduct of some corporation heads led people to become disillusioned. The incarceration of Wall Street investment advisor Bernard Madoff made international headlines as he was alleged to have defrauded investors of billions of dollars (Yin, 2001).

Sports figures feature prominently among American heroes, especially during their prime. NBA basketball player Michael Jordan epitomizes the modern-day American hero. Jordan’s hero status is vested in his ability to bridge the world of sports and business with unmatched success. The media promoted Jordan’s hero image intensively, and he was marketed commercially by Nike, who produced his “Air Jordans” shoes (Walters, 1997). His unauthorized 1999 film biography is titled Michael Jordan: An American Hero , and it focuses on how Jordan triumphed over obstacles, such as racial prejudice and personal insecurities, to become a role model on and off the basketball court.

The 9/11 terrorist attacks prompted Americans to make heroes of ordinary people who performed in extraordinary ways in the face of adversity. Firefighters and police officers who gave their lives, recovered victims, and protected people from further threats were honored in numerous ceremonies. Also treated as heroes were the passengers of Flight 93 who attempted to overtake the terrorists who had hijacked their plane, which was believed to be headed for a target in Washington, DC. The plane crashed in a Pennsylvania field.

Subcultures

Political subcultures are distinct groups, associated with particular beliefs, values, and behavior patterns, that exist within the overall framework of the larger culture. They can develop around groups with distinct interests, such as those based on age, sex, race, ethnicity, social class, religion, and sexual preference. Subcultures also can be geographically based. Political scientist Daniel Elazar identified regional political subcultures, rooted in American immigrant settlement patterns, that influenced the way that government was constituted and practiced in different locations across the nation. The moral political subculture, which is present in New England and the Midwest, promotes the common good over individual values. The individual political subculture, which is evident in the middle Atlantic states and the West, is more concerned with private enterprise than societal interests. The traditional political subculture, which is found in the South, reflects a hierarchical societal structure in which social and familial ties are central to holding political power (Elazar, 1972). Political subcultures can also form around social and artistic groups and their associated lifestyles, such as the heavy metal and hip-hop music subcultures.

Although the definition of political culture emphasizes unifying, collective understandings, in reality, cultures are multidimensional and often in conflict. When subcultural groups compete for societal resources, such as access to government funding for programs that will benefit them, cultural cleavages and clashes can result. As we will see in the section on multiculturalism, conflict between competing subcultures is an ever-present fact of American life.

Multiculturalism

One of the hallmarks of American culture is its racial and ethnic diversity. In the early twentieth century, the playwright Israel Zangwill coined the phrase “ melting pot ” to describe how immigrants from many different backgrounds came together in the United States. The melting pot metaphor assumed that over time the distinct habits, customs, and traditions associated with particular groups would disappear as people assimilated into the larger culture. A uniquely American culture would emerge that accommodated some elements of diverse immigrant cultures in a new context (Fuchs, 1990). For example, American holiday celebrations incorporate traditions from other nations. Many common American words originate from other languages. Still, the melting pot concept fails to recognize that immigrant groups do not entirely abandon their distinct identities. Racial and ethnic groups maintain many of their basic characteristics, but at the same time, their cultural orientations change through marriage and interactions with others in society.

Over the past decade, there has been a trend toward greater acceptance of America’s cultural diversity. Multiculturalism celebrates the unique cultural heritage of racial and ethnic groups, some of whom seek to preserve their native languages and lifestyles. The United States is home to many people who were born in foreign countries and still maintain the cultural practices of their homelands.

Multiculturalism has been embraced by many Americans, and it has been promoted formally by institutions. Elementary and secondary schools have adopted curricula to foster understanding of cultural diversity by exposing students to the customs and traditions of racial and ethnic groups. As a result, young people today are more tolerant of diversity in society than any prior generation has been. Government agencies advocate tolerance for diversity by sponsoring Hispanic and Asian American/Pacific Islander heritage weeks. The US Postal Service has introduced stamps depicting prominent Americans from diverse backgrounds.

Despite these trends, America’s multiculturalism has been a source of societal tension. Support for the melting pot assumptions about racial and ethnic assimilation still exists (Hunter & Bowman, 1996). Some Americans believe that too much effort and expense is directed at maintaining separate racial and ethnic practices, such as bilingual education. Conflict can arise when people feel that society has gone too far in accommodating multiculturalism in areas such as employment programs that encourage hiring people from varied racial and ethnic backgrounds (Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, 1999).

Key Takeaways

Political culture is defined by the ideologies, values, beliefs, norms, customs, traditions, and heroes characteristic of a nation. People living in a particular political culture share views about the nature and operation of government. Political culture changes over time in response to dramatic events, such as war, economic collapse, or radical technological developments. The core American values of democracy and capitalism are vested in the American creed. American exceptionalism is the idea that the country has a special place in the world because of the circumstances surrounding its founding and the settling of a vast frontier.

Rituals, traditions, and symbols bond people to their culture and can stimulate national pride. Folklore consists of stories about a nation’s leaders and heroes; often embellished, these stories highlight the character traits that are desirable in a nation’s citizens. Heroes are important for defining a nation’s political culture.

America has numerous subcultures based on geographic region; demographic, personal, and social characteristics; religious affiliation, and artistic inclinations. America’s unique multicultural heritage is vested in the various racial and ethnic groups who have settled in the country, but conflicts can arise when subgroups compete for societal resources.

- What do you think the American flag represents? Would it bother you to see someone burn an American flag? Why or why not?

- What distinction does the text make between beliefs and values? Are there things that you believe in principle should be done that you might be uncomfortable with in practice? What are they?

- Do you agree that America is uniquely suited to foster freedom and equality? Why or why not?

- What characteristics make you think of someone as particularly American? Does race or cultural background play a role in whether you think of a person as American?

Bennett, W. L., Public Opinion in American Politics (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1980), 368.

Dreher, R., “The Bravest Speak,” National Review Online , January 16, 2002.

Elazar, D. J., American Federalism: A View From the States, 2nd ed. (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1972).

Elazar, D. J., The American Mosaic (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1994).

Fuchs, L. H., The American Kaleidoscope . (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1990).

George Washington’s Mount Vernon, “Did George Washington really throw a silver dollar across the Potomac River?,” accessed February 3, 2011, http://www.mountvernon.org/knowledge/index.cfm/fuseaction/view/KnowledgeID/20 .

George Washington’s Mount Vernon, “Is it true that George Washington chopped down a cherry tree when he was a boy?,” accessed February 3, 2011, http://www.mountvernon.org/knowledge/index.cfm/fuseaction/view/KnowledgeID/21 .

Ginsberg, B. and Herbert Weissberg, “Elections and the Mobilization of Popular Support,” American Journal of Political Science 22, no.1 (1978): 31–55.

Greenstein, F. I., Children and Politics (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1969).

Hunter, J. D. and Carl Bowman, The State of Disunion (Charlottesville, VA: In Media Res Educational Foundation, 1996).

Inglehart, R., Culture Shift in Advanced Industrial Society (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990).

Kitwana, B., The Hip-Hop Generation (New York: Basic Civitas Books, 2002).

Lewis, A., “Vilification of Black Youth Culture by the Media” (master’s thesis, Georgetown University, 2003).

Marable, M., “The Politics of Hip-Hop,” The Urban Think Tank , 2 (2002). http://www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/45a/594.html .

McClosky, H. and John Zaller, The American Ethos (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987).

Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, Retro-Politics: The Political Typology (Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, November 11, 1999).

Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, Values Survey (Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, March 2009).

Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, Views of Business and Regulation Remain Unchanged (Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, February 21, 2001).

Sullivan, J. L., James Piereson, and George E. Marcus, Political Tolerance and American Democracy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982).

Walters, P., “Michael Jordan: The New American Hero” (Charlottesville VA: The Crossroads Project, 1997).

Wilson, R. W., “American Political Culture in Comparative Perspective,” Political Psychology , 18, no. 2 (1997): 483–502.

Yin, S., “Shifting Careers,” American Demographics , 23, no. 12 (December 2001): 39–40.

American Government and Politics Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

SOCIALSTUDIESHELP.COM

Exploring us political culture: an in-depth essay, american political culture, introduction.